3. Methods

The interactive visualisation tool for the street network is developed on a custom built computer with an Ryzen 5800×, 3070 ti, 32 GB ram and also an Intel i5 11th gen laptop. The study utilises two primary datasets provided by the New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA), extracted on 1 October 2023. These datasets were selected to benchmark performance across different network scales: ‘Wellington_highway_vertices.tsv’ (34,423 elements) representing a medium-density urban network, and ‘barry_akl.csv’ (1,327,491 elements) representing a high-density metropolitan network (Auckland). The geospatial data is provided in both WGS84 (EPSG:4326) format for web-based visualisation and New Zealand Transverse Mercator (NZTM, EPSG:2193) for metric analysis. The Python code is created in either a basic script file which outputs a HTML or can be created in a Jupyter notebook which generates a visualisation in the notebook. The Jupyter notebook can avoid the issue with extremely large datasets that exceed most browsers built-in limit of 1 GB.

The Python code is created in either a basic script file which outputs a HTML file or can be created in a Jupyter notebook which generates a visualisation in the notebook. The Jupyter notebook can avoid the issue with extremely large datasets that exceed most browsers’ built-in limit of 1GB. The code relies on the following Python libraries: pandas for data manipulation and analysis, numpy for numerical computations, and PyDeck version 0.9.1.

3.3. OpenStreetMap Data Structure

OpenStreetMap (OSM) data [

25] presents unique challenges for network visualisation due to its encoding of bidirectional roads. In raw OSM data, a single ’way’ with tags indicating one or two-way streets is used to represent roads. However, when this data is transformed by National Network Performance (NNP) into a digraph for network analysis, bidirectional roads are represented as duplicate coordinate sequences in reverse order. For example, consider the following coordinate sequences from Buller Street in Wellington:

[(−41.2934713, 174.7708912), (−41.2934969, 174.7709145),

(−41.2935152, 174.7709333), (−41.2935389, 174.7709976),

(−41.2935606, 174.7710564)]

[(−41.2935606, 174.7710564), (−41.2935389, 174.7709976),

(−41.2935152, 174.7709333), (−41.2934969, 174.7709145),

(-41.2934713, 174.7708912)]

These coordinates represent the same physical road segment but in opposite directions, resulting from NNP’s transformation of OSM data into a digraph structure. When visualised directly, these duplicate segments would occupy identical spatial positions, making it impossible to distinguish between opposite travel directions. This transformed data structure, while logical for network analysis and querying, creates significant visualisation challenges when attempting to represent directional traffic flows clearly.

Bidirectional roads represent a majority of urban road networks, and without proper processing, visualisations would appear cluttered and ambiguous, with overlapping lines making it difficult to interpret network structure and traffic flow patterns. This characteristic of NNP-transformed OSM data makes specialised processing not merely advantageous but essential for effective network visualisation and error identification.

| Algorithm 6 Turn Path Generation |

- 1:

procedure GenerateTurnPaths(junction_key, junction_data) - 2:

Get junction type (T-junction, 4-way, etc.) - 3:

Get junction coordinates - 4:

▹ Position nodes 20% from junction - 5:

for all incoming directions with valid data do - 6:

Get adjacent point coordinates from road data - 7:

Calculate interpolated position along road segment: - 8:

- 9:

- 10:

Initialise empty possible_turns list - 11:

for all potential turn directions turn_dir do - 12:

if turn_dir = incoming_dir then - 13:

continue ▹ Skip the incoming direction itself - 14:

end if - 15:

Validate turn using Algorithm 5 ▹ Check one-way constraints - 16:

if turn is valid then - 17:

Determine turn label (’straight’, ’left’, ’right’, etc.) - 18:

Add turn to possible_turns - 19:

end if - 20:

end for - 21:

Create node with position, direction, and valid turns data - 22:

end for - 23:

return list of visualisation nodes - 24:

end procedure

|

| Algorithm 7 Street Offset Calculation |

- 1:

procedure OffsetCoordinates(coordinates, is_oneway, offset_distance) - 2:

if is_oneway is True then - 3:

return original coordinates unchanged - 4:

end if - 5:

Initialize empty offset_coords list - 6:

for each consecutive point pair in coordinates do - 7:

Calculate direction vector - 8:

Compute length - 9:

if then - 10:

Add original start point to offset_coords - 11:

continue to next iteration - 12:

end if - 13:

Calculate perpendicular direction: - 14:

where =offset_distance - 15:

Create new offset point: - 16:

- 17:

Add new_start to offset_coords - 18:

if processing second-to-last point then - 19:

Create offset end point: - 20:

- 21:

Add new_end to offset_coords - 22:

end if - 23:

end for - 24:

return offset_coords - 25:

end procedure

|

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and E.M.-K.L.; methodology, J.Y.N., J.M. and A.S.; software, J.Y.N.; validation, S.H.; formal analysis, J.Y.N.; investigation, J.Y.N.; resources, S.H.; data curation, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.N.; writing—review & editing, J.M. and A.S.; visualisation, J.Y.N.; supervision, J.M. and A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Auckland University of Technology, 2024–2025 summer research project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by New Zealand Transport Agency. The datasets and related assistance offered by NZTA are gratefully acknowledged. We would also like to thank Milcent Mugandane for her initial exploration of alternative visualisation methods which helped inform the direction of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Neira, M.; Murcio, R. Graph representation learning for street networks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.04984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.J.; Nelson, A.; Gibson, H.; Temperley, W.; Peedell, S.; Lieber, A.; Hancher, M.; Poyart, E.; Belchior, S.; Fullman, N.; et al. A global map of travel time to cities to assess inequalities in accessibility in 2015. Nature 2018, 553, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinberger, A.Y.; Minghini, M.; Yeboah, G.; Juhász, L.; Mooney, P. Bridges and barriers: An exploration of engagements of the research community with the OpenStreetMap community. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, G. Street network models and measures for every US City, county, urbanized area, census tract, and zillow-defined neighborhood. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karduni, A.; Kermanshah, A.; Derrible, S. A protocol to convert spatial polyline data to network formats and applications to world urban road networks. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addepalli, L.; Lokhande, G.; Sakinam, S.; Hussain, S.; Mookerjee, J.; Vamsi, U.; Waqas, A.; Vidya Sagar, S.D. Assessing the Performance of Python Data Visualization Libraries: A Review. Int. J. Comput. Eng. Res. Trends 2023, 10, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, D.; Gede, M. Vector Data Rendering Performance Analysis of Open-Source Web Mapping Libraries. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, R.; Tong, D.; Lim, S.; Sohn, G.; Gidófalvi, G. A framework for performance analysis of OpenStreetMap data in navigation applications: The case of a well-developed road network in Australia. Ann. GIS 2025, 31, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Roche, S.; Mostafavi, M.A. Exploring five indicators for the quality of OpenStreetMap road networks: A case study of Québec, Canada. Geomatica 2022, 75, 178–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; She, Y.; Chen, W.; Lu, Y.; Xia, J.; Chen, W.; Liu, J.; Zhou, F. Eod edge sampling for visualizing dynamic network via massive sequence view. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 53006–53018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xu, J.; Yang, J.; Duan, J. A global urban road network self-adaptive simplification workflow from traffic to spatial representation. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamis, A.; Wang, Y. From Road Network to Graph. 2021. Available online: https://smartmobilityalgorithms.github.io/book/content/GraphSearchAlgorithms/RoadGraph.html (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Riihimäki, H. Simplicial-Connectivity of Directed Graphs with Applications to Network Analysis. SIAM J. Math. Data Sci. 2023, 5, 800–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Han, X.; Chin, K.; Kong, X. An attention-based digraph convolution network enabled framework for congestion recognition in three-dimensional road networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 14413–14426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthélemy, M.; Flammini, A. Modeling urban street patterns. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 138702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Levinson, D. Measuring the structure of road networks. Geogr. Anal. 2007, 39, 336–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, G. OSMnx: New methods for acquiring, constructing, analyzing, and visualizing complex street networks. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2017, 65, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Robledo, A.; Zangiabady, M. Dash Sylvereye: A Python Library for Dashboard-Driven Visualization of Large Street Networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 121142–121161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadi, K.; Nguyen, N.H.; Alkaabi, M. The edge and the center in neighborhood planning units: Assessing permeability and edge attractiveness in Abu Dhabi. Transportation 2023, 50, 677–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobral, T.; Galvão, T.; Borges, J. Visualization of urban mobility data from intelligent transportation systems. Sensors 2019, 19, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, M. Networks, Maps, and Time: Visualizing Historical Networks Using Palladio. DHQ Digit. Humanit. Q. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, Q.; Akbaş, M.İ.; Jaimes, L.G.; Sanchez-Arias, R. Street network generation with adjustable complexity using k-means clustering. In Proceedings of the 2019 SoutheastCon, Huntsville, AL, USA, 11–14 April 2019; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Uber Technologies, Inc. PyDeck Documentation. 2024. Available online: https://pydeck.gl/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Lu, J.; Peng, R.; Cai, X.; Xu, H.; Wen, F.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L. Translating Images to Road Network: A Sequence-to-Sequence Perspective. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.08207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenStreetMap Contributors. OpenStreetMap Wiki: Tags, Layers, and Junctions Documentation. 2025. Available online: https://wiki.openstreetmap.org/wiki/Map_Features (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Filipov, V.; Arleo, A.; Miksch, S. Are We There Yet? A Roadmap of Network Visualization from Surveys to Task Taxonomies. Comput. Graph. Forum 2023, 42, e14794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, M.; Ten Brinke, K.B.; Castella, A.; Karray, G.; Peters, S.; Shteriyanov, V.; Vlasvinkel, R. Dynamic graph exploration by interactively linked node-link diagrams and matrix visualizations. Vis. Comput. Ind. Biomed. Art 2021, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barranquero, M.; Olmedo, A.; Gómez, J.; Tayebi, A.; Hellín, C.J.; Saez de Adana, F. Automatic 3D Building Reconstruction from OpenStreetMap and LiDAR Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, G. Topological Graph Simplification Solutions to the Street Intersection Miscount Problem. Trans. GIS 2025, 29, e70037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

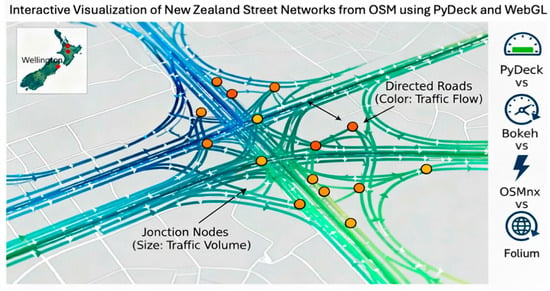

Figure 1.

Data processing and visualisation pipeline showing the interconnection between different algorithms and processing stages.

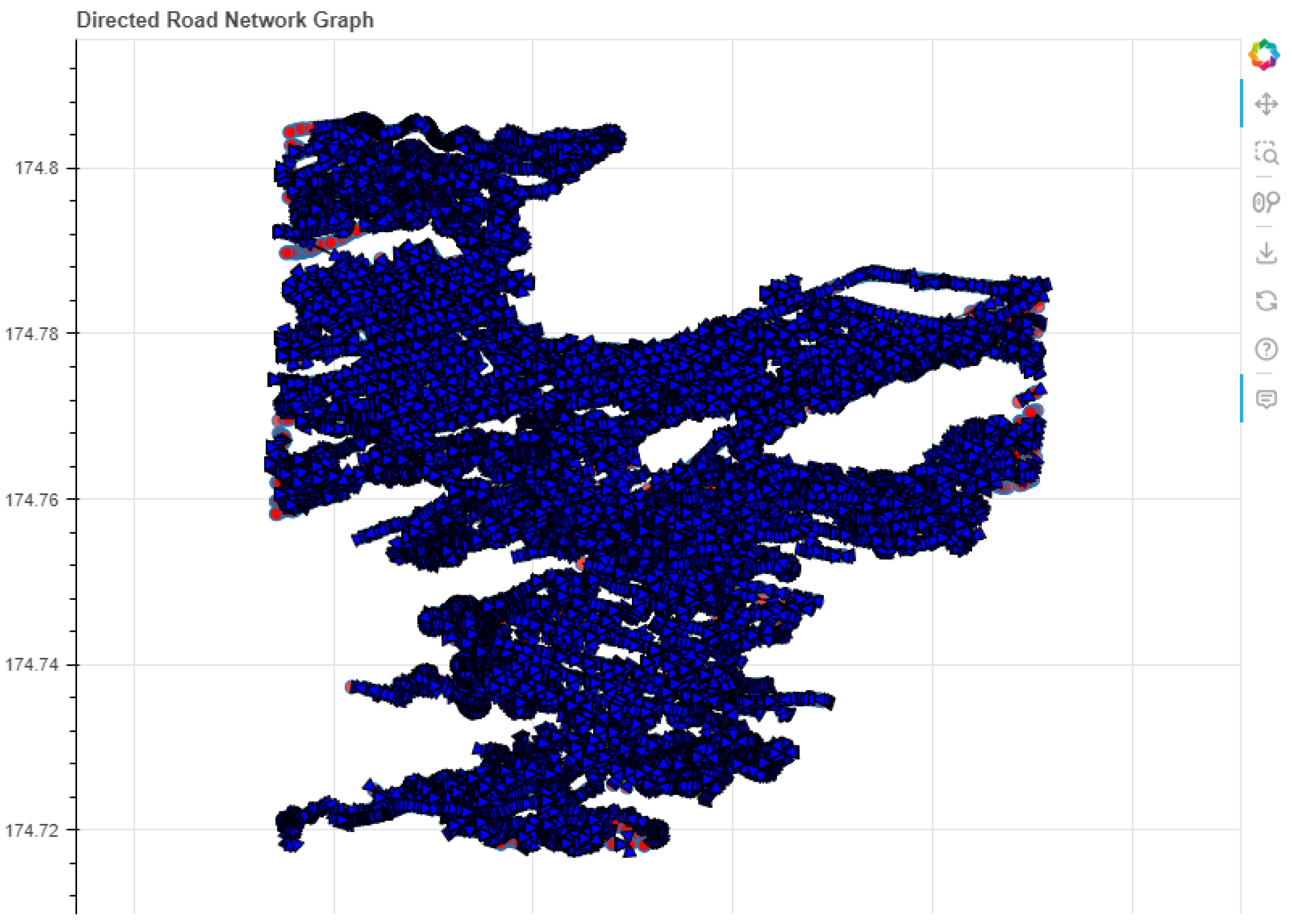

Figure 2.

Bokehvisualization of Wellington road network showing limited visual clarity and heavy resource usage (378.87 s execution time, 856.34 MB memory). (Colour Legend: Blue arrows = road direction indicators; Red markers = junction nodes).

Figure 3.

PyDeck visualization of Wellington with improved clarity and efficient resource usage (1.59 s execution time, 177.05 MB memory). The visual density represents the macroscopic scale; specific edge and node interactions are detailed in subsequent figures. (Colour Legend: Blue lines = North/East traffic flow; Red lines = South/West traffic flow. Note: Dense overlapping lines represent high-density urban infrastructure).

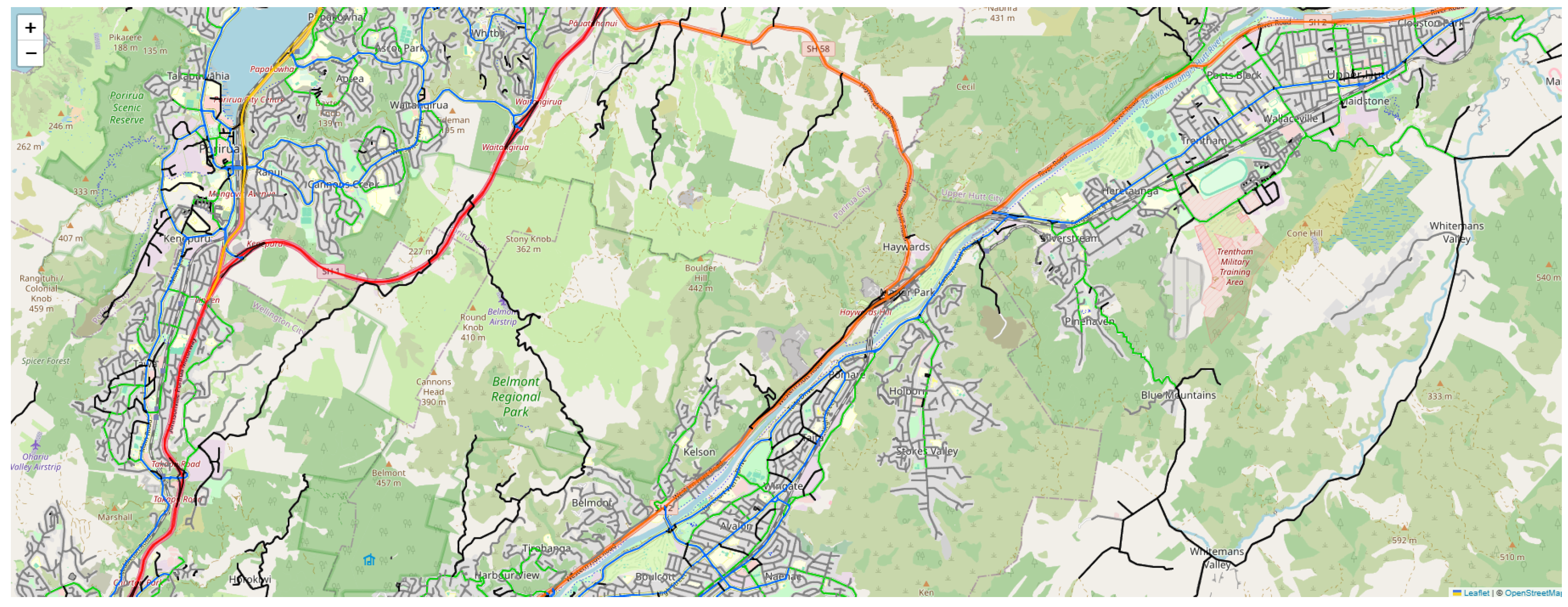

Figure 4.

OSMnx visualization of Wellington showing detailed road hierarchy but with significant resource overhead (42.76 s execution time, 708.15 MB memory). The dense overlapping content accurately reflects the complexity of the metropolitan road network at a macro scale. (Colour Legend: Different line colors represent distinct road hierarchy levels, such as motorways, arterial, and residential streets).

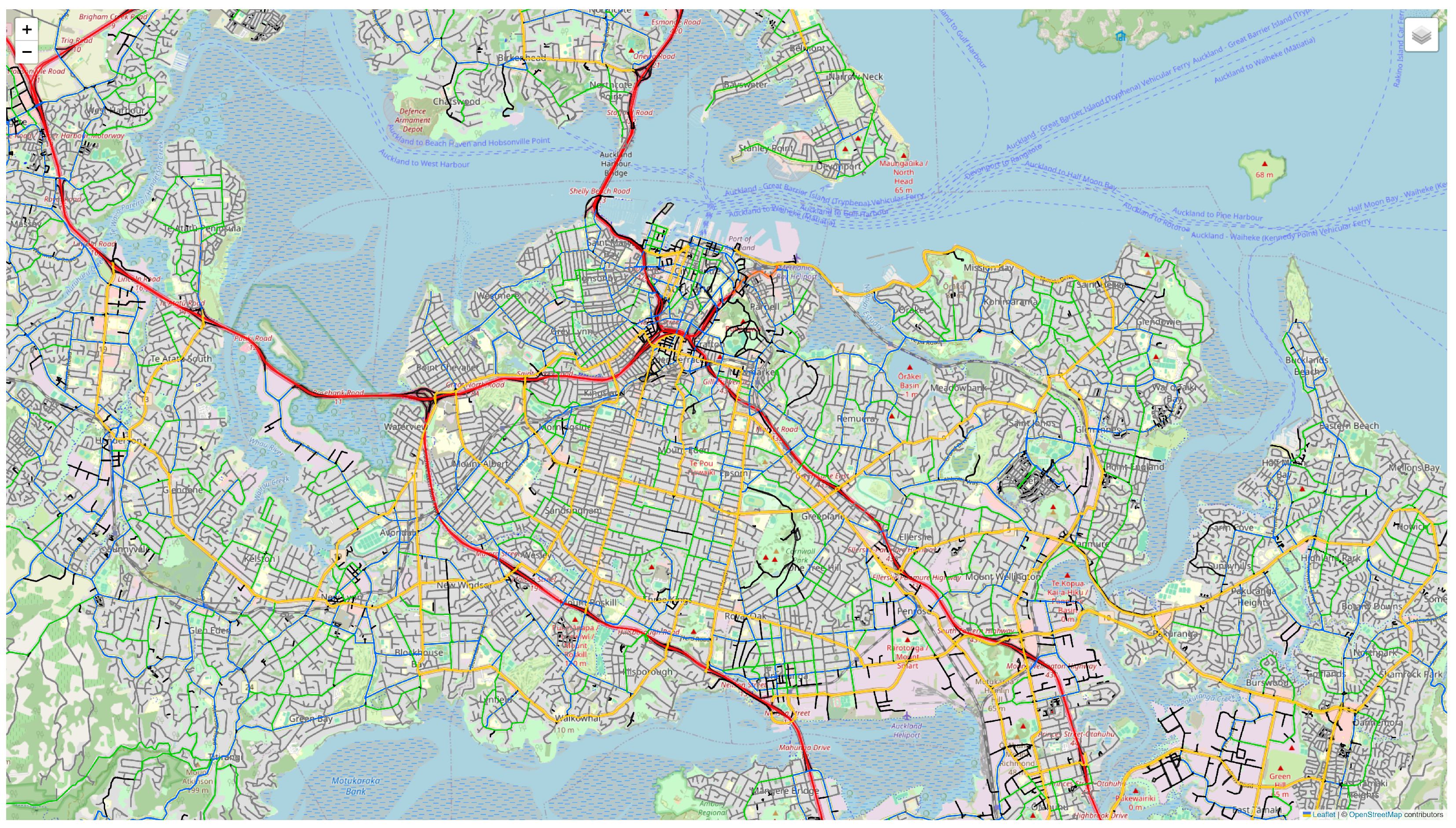

Figure 5.

OSMnxvisualization of Auckland showing detailed road hierarchy but with significant resource overhead (175.79 s execution time, 1977.25 MB memory). The dense overlapping content accurately reflects the complexity of the metropolitan road network at a macro scale. (Colour Legend: Different line colors represent distinct road hierarchy levels, such as motorways, arterial, and residential streets).

Figure 6.

PyDeck visualization of Auckland demonstrating superior performance with large datasets (26.88 s execution time, 1621.29 MB memory). Overlapping lines indicate high-density urban infrastructure. (Color Legend: Blue lines = North/East traffic flow; Red lines = South/West traffic flow; Distinct coloured nodes = Turn possibilities).

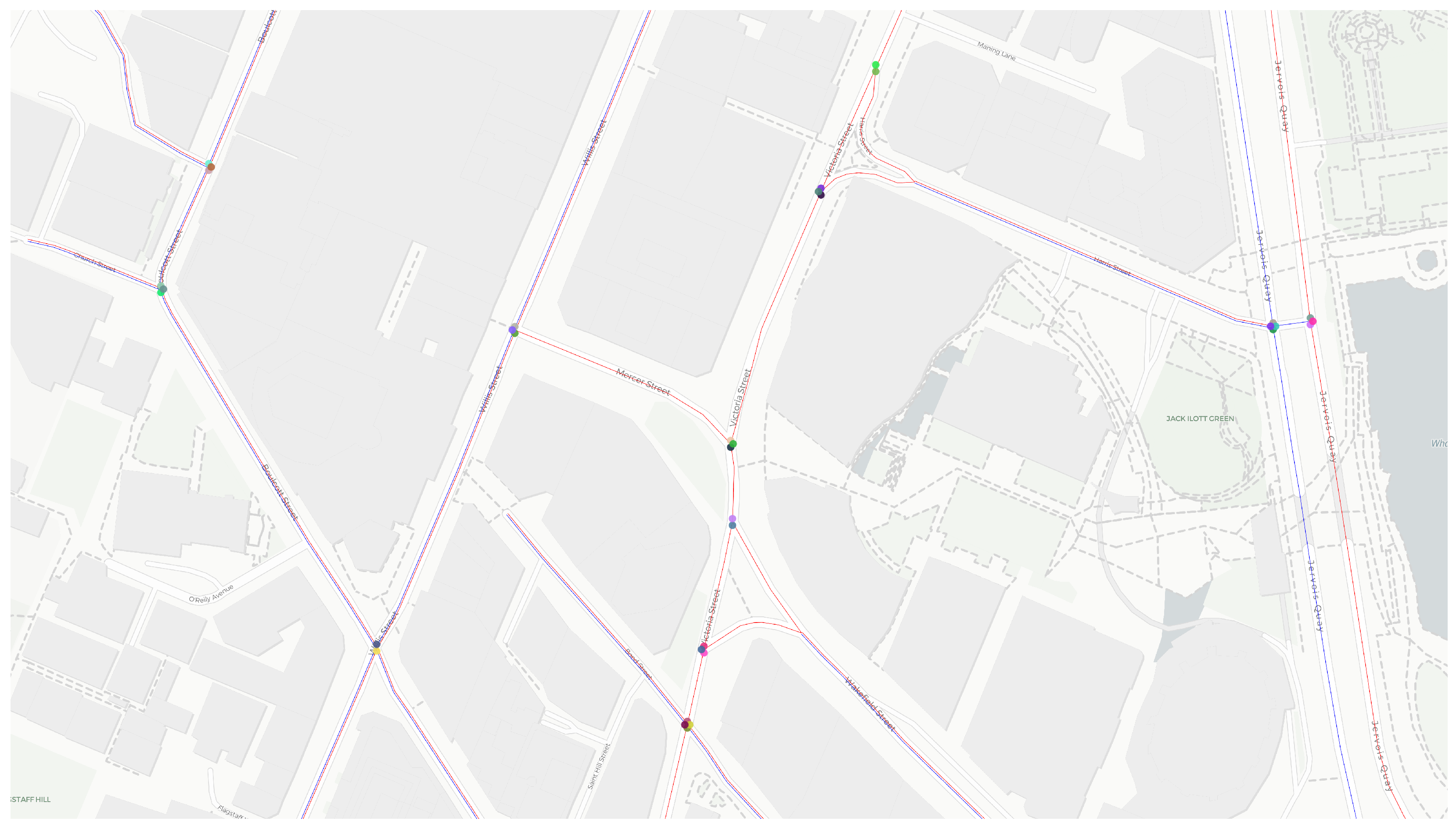

Figure 7.

Interactive junction visualisation showing turn possibilities at a 4-way intersection. The tooltip displays available turns for Jervois Quay. (Colour Legend: Blue lines = North/East-bound traffic; Red lines = South/West-bound traffic; Distinct coloured nodes = Turn possibilities).

Figure 8.

Visualization of one-way roads in Wellington’s CBD. The single-colored lines indicate one-way traffic flow on Courtenay Place, verified by satellite imagery. (Colour Legend: Blue = North/East flow; Red = South/West flow. Parallel Red/Blue lines indicate bidirectional roads; Distinct coloured nodes = Turn possibilities).

Figure 9.

Multi-layer road representation showing the Wellington Urban Motorway passing beneath Salamanca Road. While these roads appear to intersect in 2D coordinates, they exist at different elevations—the motorway in a tunnel (lower layer) and Cliffton Terrace at ground level (base layer). (Colour Legend: Blue/Red lines = traffic flow direction. The absence of a node marker at the crossover point visually confirms the grade separation).

Table 1.

Bokeh and PyDeck Comparison in Wellington Dataset (∼12.5 MB).

| Metric | PyDeck | Bokeh |

|---|

| Total Execution (s) | 1.59 | 378.87 |

| Output Size (MB) | 49.05 | 715.01 |

| Memory Usage (MB) | 177.05 | 856.34 |

| Frame Rate (FPS) | 60 | 15–30 |

Table 2.

Bokeh and PyDeck Comparison in Auckland Dataset (∼392.2 MB).

| Metric | PyDeck | Bokeh |

|---|

| Total Execution (s) | 26.88 | DNF |

| Output Size (MB) | 821.55 | DNF |

| Memory Usage (MB) | 1621.29 | DNF |

| Frame Rate (FPS) | 60 | DNF |

Table 3.

OSMnx and PyDeck Comparison in Wellington Dataset (∼12.5 MB).

| Metric | PyDeck | OSMnx + Folium |

|---|

| Total Execution (s) | 1.59 | 42.76 |

| Output Size (MB) | 49.05 | 708.15 |

| Memory Usage (MB) | 177.05 | 899.60 |

| Frame Rate (FPS) | 60 | 60 |

Table 4.

OSMnx and PyDeck Comparison in Auckland Dataset (∼392.2 MB).

| Metric | PyDeck | OSMnx + Folium |

|---|

| Total Execution (s) | 26.88 | 175.79 |

| Output Size (MB) | 821.55 | 1785.64 |

| Memory Usage (MB) | 1621.29 | 1977.25 |

| Frame Rate (FPS) | 60 | 60 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).