OTSU-UCAN: An OTSU-Based Integrated Satellite–Terrestrial Information System for 6G in Vehicle Navigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

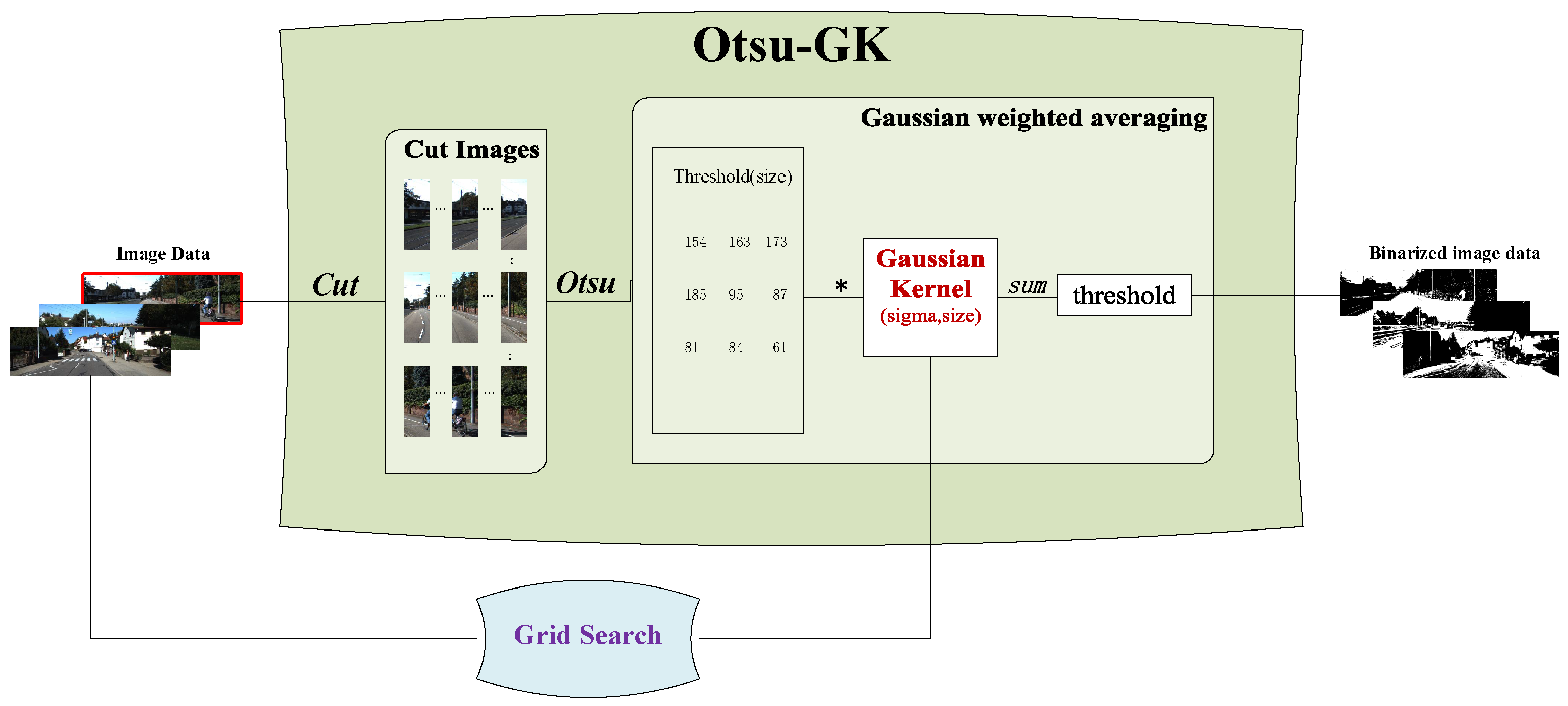

- OTSU-GK: The OTSU-GK is a new adaptive thresholding approach, which integrates a Gaussian kernel. The parameters of the Gaussian kernel are optimized through grid search to enhance threshold calculation. OTSU-GK provides a new solution in the field of image binarization.

- Node Load Score-based (NLS) sharding blockchain: We propose a blockchain segmentation method based on node load scoring to segment blockchain nodes by predicting the number of transactions of each node in the next epoch and calculating the corresponding transaction load scoring, which reflects the node’s transaction load, with the aim of achieving load balancing between segments.

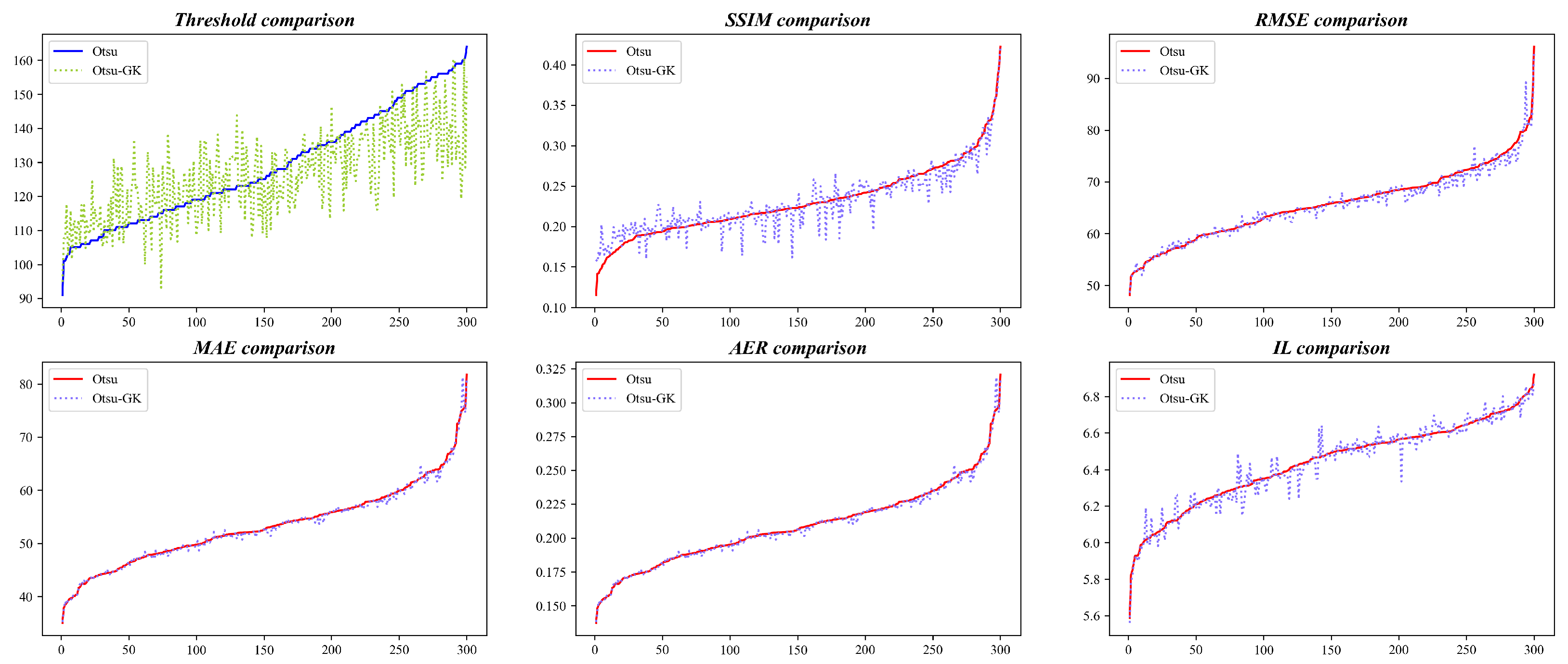

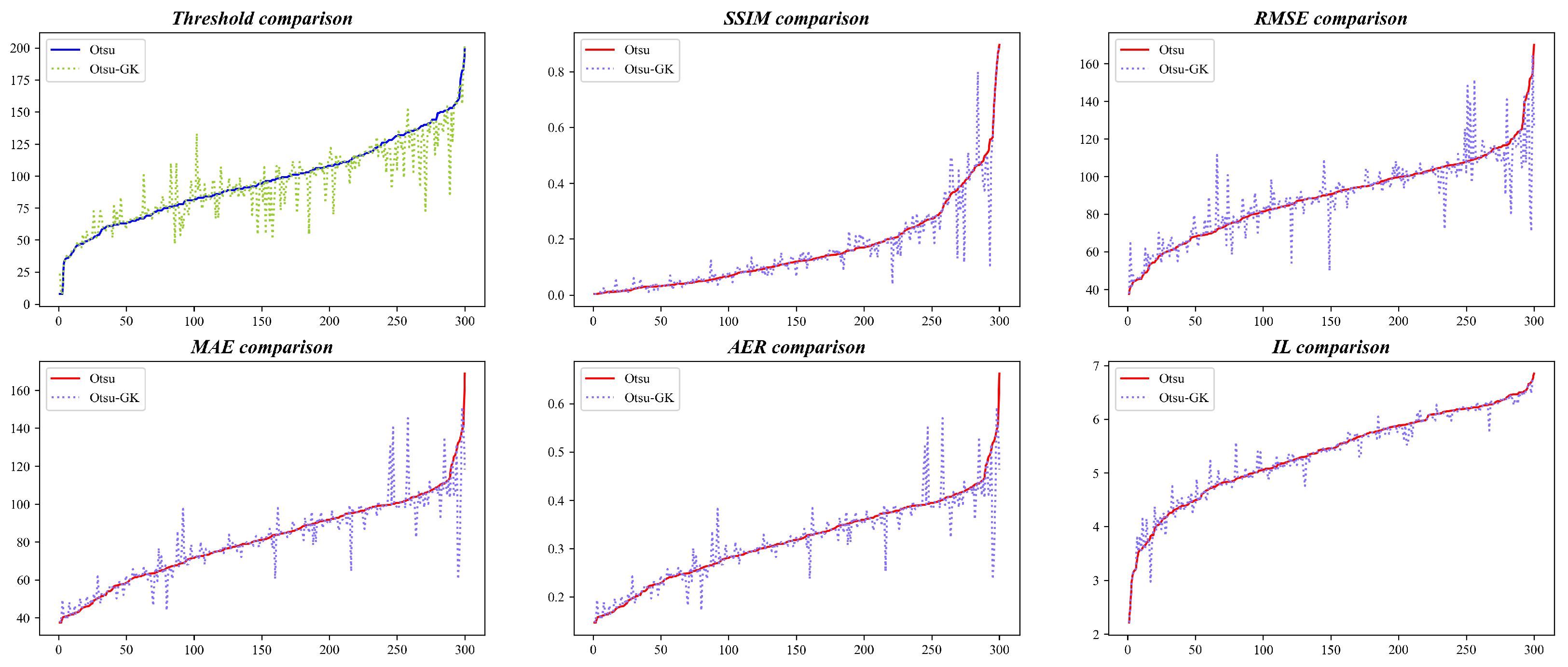

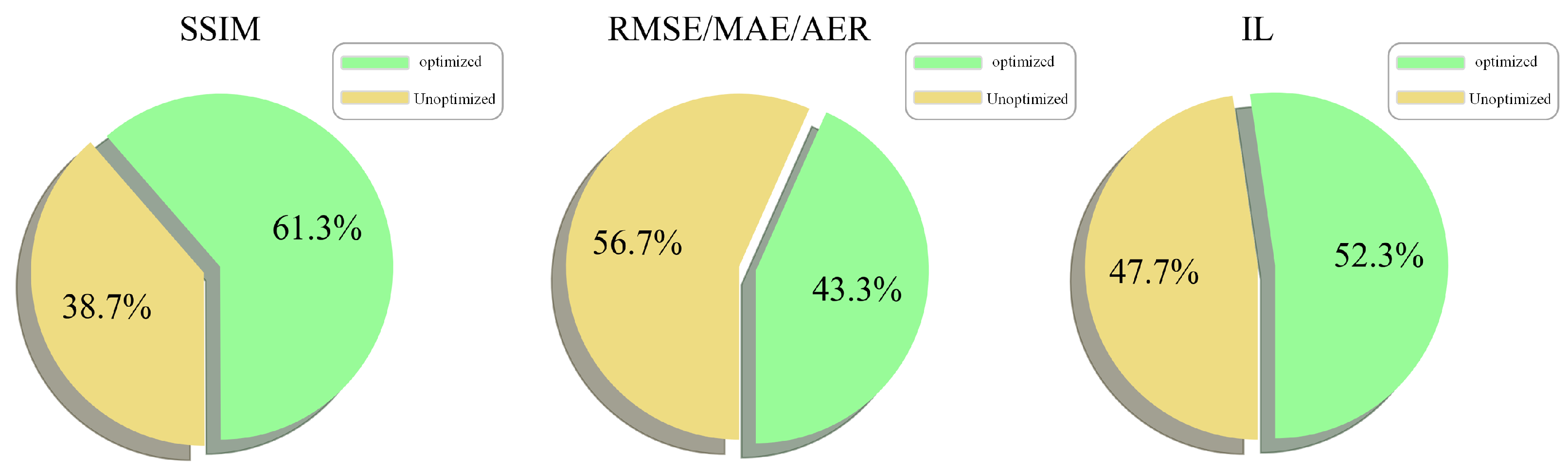

- Significant Performance Improvement: Compared to the traditional OTSU method, OTSU-GK shows approximately 50% improvement in SSIM (Structural Similarity), RMSE (root mean square error), and IL (information loss). This indicates that OTSU-GK performs better in image processing, thereby supporting the advancement of embedded image processing.

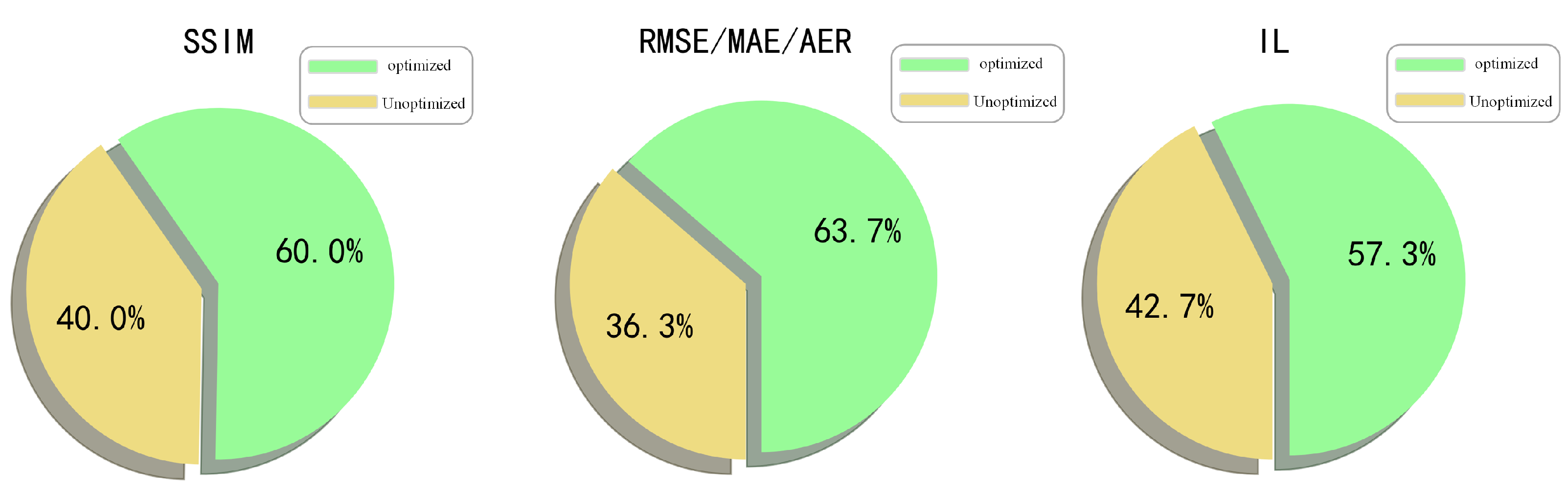

- Effectiveness of Parameter Optimization: Ablation experiments confirm the effectiveness of parameter optimization through grid search. When compared to methods with non-optimized parameters, OTSU-GK demonstrates a 14.3% increase in the SSIM metric and a 13% reduction in the IL metric on the KITTI dataset, which indicates that the process of optimizing parameters significantly enhances the performance of OTSU-GK.

2. Related Work

2.1. Image Binarization

2.2. Optimization Methods of Hyperparameters

2.3. Sharding Blockchain

3. Method

3.1. Framework of OTSU-GK

- Grid Search: We employ grid search for hyperparameter tuning, specifically to optimize the two hyperparameters of the Gaussian kernel, sigma () and size, which determine the number of cut images (see Section 3.2 for details).

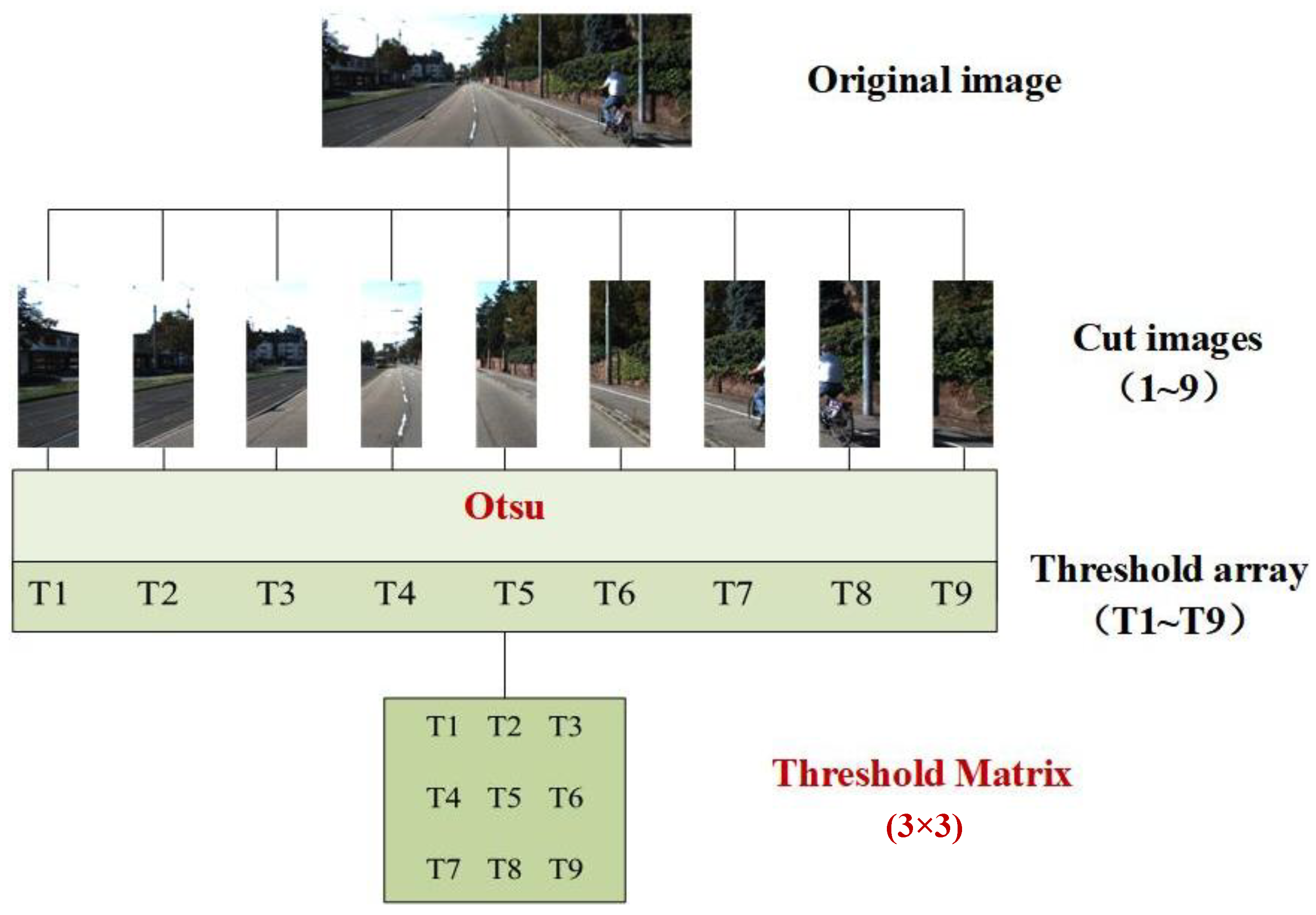

- Cut Images: We select original images from the dataset and perform proportional slicing from left to right. OTSU thresholding is then applied to each sliced image, resulting in a corresponding threshold matrix (see Section 3.3 for details).

- Gaussian Kernel Average: The Gaussian kernel performs matrix multiplication with the threshold matrices generated from the cut images. The resulting matrix is summed to determine the final threshold value for the original image, which is then used for binarization (see Section 3.4 for details).

3.2. Grid Search

| Algorithm 1 Grid search for hyperparameter tuning |

|

3.3. Cut-Image Generation

3.4. Experimental Settings

3.4.1. Cut Images

3.4.2. Gaussian Kernel Average

4. NLS-Chain: NLS Sharding Blockchain

4.1. Prediction of the Number of Node Transactions

| Algorithm 2 The generation of a transaction sequence |

|

4.2. Sharding Method Based on NLS

NLS Calculation

4.3. NLS-Chain: Load-Balanced Sharding via NLS

4.3.1. Optimization Objective

- Sort nodes by descending ;

- Round-robin assignment to obtain equal-sized shards;

- Iteratively migrate the node that yields the largest marginal reduction in (6) until no improvement is possible.

4.3.2. Throughput Evaluation

5. Experiment

5.1. Results of OTSU-GK

5.2. Ablation Study

5.3. Throughput of NLS-Chain

- Random: Nodes and transactions are randomly assigned to shards.

- LB-Chain: It predicts node traffic via LSTM and re-shards through account migration.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, S.; Chen, L.; Hu, B.; Sun, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.W.; Gao, W. User-centric access network (UCAN) for 6G: Motivation, concept, challenges and key technologies. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2024, 22, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.G. Design for Embedded Image Processing on FPGAs; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J. Threshold variability in subliminal perception experiments: Fixed threshold estimates reduce power to detect subliminal effects. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1991, 17, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Song, W.; Zhao, X.; Zheng, R.; Qingge, L. An improved Otsu threshold segmentation algorithm. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2020, 22, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.-D. Adaptive threshold image segmentation based on definition evaluation. J. Northeast. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2020, 41, 1231. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Tian, L.; Du, Q.; Qin, C. Improved decision based adaptive threshold median filter for fingerprint image salt and pepper noise denoising. In Proceedings of the 2022 21st International Symposium on Communications and Information Technologies (ISCIT), Xi’an, China, 27–30 September 2022; pp. 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; He, W. Single-image dehazing via dark channel prior and adaptive threshold. Int. J. Image Graph. 2021, 21, 2150053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.A.; Jeffrey, Z.; Sun, Y.; Simpson, O. Image enhancement using modified Laplacian filter, CLAHE and adaptive thresholding. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Computer Vision (ISCV), Fez, Morocco, 8–10 May 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; El-Khamy, M.; Lee, J. T-GSA: Transformer with Gaussian-weighted self-attention for speech enhancement. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Barcelona, Spain, 4–8 May 2020; pp. 6649–6653. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Chen, B.; Zhao, Z.; Song, B. Point cloud registration based on learning Gaussian mixture models with global-weighted local representations. IEEE Geosci. Remote. Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 6500505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryowati, K.; Ranggo, M.O.; Bekti, R.D.; Sutanta, E.; Riswanto, E. Geographically weighted regression modeling using fixed and adaptive Gaussian kernel weighting functions in the analysis of maternal mortality (MMR). In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Electronics Representation and Algorithm (ICERA), Virtual, 29–30 July 2021; pp. 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Basteri, A.; Trevisan, D. Quantitative Gaussian approximation of randomly initialized deep neural networks. Mach. Learn. 2024, 113, 6373–6393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shami, A. On hyperparameter optimization of machine learning algorithms: Theory and practice. Neurocomputing 2020, 415, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.; Eriksson, D.; McCourt, M.; Kiili, J.; Laaksonen, E.; Xu, Z.; Guyon, I. Bayesian optimization is superior to random search for machine learning hyperparameter tuning: Analysis of the black-box optimization challenge 2020. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2020 Competition and Demonstration Track, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Alhijawi, B.; Awajan, A. Genetic algorithms: Theory, genetic operators, solutions, and applications. Evol. Intell. 2024, 17, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, L.; Narayanan, V.; Zheng, C.; Baweja, K.; Saxena, P. A secure sharding protocol for open blockchains. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kokoris-Kogias, E.; Jovanovic, P.; Gasser, L.; Gailly, N.; Syta, E.; Ford, B. OmniLedger: A secure, scale-out, decentralized ledger via sharding. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 21–23 May 2018; pp. 583–598. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, P.; Chen, W. Pyramid: A layered sharding blockchain system. In Proceedings of the 40th IEEE Conference on Computer Communications (INFOCOM), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–13 May 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J. LB-chain: Load-balanced and low-latency blockchain sharding via account migration. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2023, 34, 2797–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, R.; Salem, F.M. Gate-variants of gated recurrent unit (GRU) neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE 60th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Boston, MA, USA, 6–9 August 2017; pp. 1597–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, G.S.; Bai, X.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Z.; Belongie, S.; Luo, J.; Datcu, M.; Pelillo, M.; Zhang, L. DOTA: A large-scale dataset for object detection in aerial images. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Shard Size | Random | LB-Chain | NLS-Chain |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 276 | 323 | 392 |

| 8 | 477 | 512 | 670 |

| 16 | 612 | 713 | 873 |

| 32 | 895 | 1362 | 1955 |

| Method | SSIM * | RMSE | MAE | AER | IL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OTSU | 0.5230 | 90.10 | 80.04 | 0.314 | 6.156 |

| MEAN | 0.1903 | 123.53 | 108.05 | 0.424 | 6.066 |

| GAUSSIAN | 0.1748 | 127.91 | 112.37 | 0.441 | 6.092 |

| Method | SSIM ↑ | RMSE ↓ | IL ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|

| OTSU-GK | +60.0% | +63.7% | +57.3% |

| OTSU-GK * | +74.3% | +58.7% | +70.3% |

| Shards | Random | LB-Chain | NLS-Chain |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 276 | 323 | 392 |

| 8 | 477 | 512 | 670 |

| 16 | 612 | 713 | 873 |

| 32 | 895 | 1362 | 1955 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Lu, K.; Cao, G.; Fan, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, B.; Li, T. OTSU-UCAN: An OTSU-Based Integrated Satellite–Terrestrial Information System for 6G in Vehicle Navigation. Information 2025, 16, 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121072

Li Y, Lu K, Cao G, Fan S, Zhang M, Li B, Li T. OTSU-UCAN: An OTSU-Based Integrated Satellite–Terrestrial Information System for 6G in Vehicle Navigation. Information. 2025; 16(12):1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121072

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yawei, Kui Lu, Gang Cao, Shuyu Fan, Mingyue Zhang, Bohan Li, and Tao Li. 2025. "OTSU-UCAN: An OTSU-Based Integrated Satellite–Terrestrial Information System for 6G in Vehicle Navigation" Information 16, no. 12: 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121072

APA StyleLi, Y., Lu, K., Cao, G., Fan, S., Zhang, M., Li, B., & Li, T. (2025). OTSU-UCAN: An OTSU-Based Integrated Satellite–Terrestrial Information System for 6G in Vehicle Navigation. Information, 16(12), 1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121072