2. Related Work

There has been a long line of research aimed at identifying and validating predictors of text complexity. Each of the five paradigms of discourse complexology, i.e., formative, classical, closed tests, constructive-cognitive, and Natural Language Processing, experimented with a new approach expanding the earlier models [

12] In their systematic review, AlKhuzaey et al. [

13] observed that traditional methods for assessing text difficulty predominantly rely on syntactic features, which are usually extracted using NLP tools—such as counts of complex words [

14], sentence length [

15], and overall word count [

16]. In contrast, recent research has increasingly turned to semantic-level analysis, enabled by advances in semantically annotated data structures such as domain ontologies and the emergence of neural language models. Among the earliest and most influential surface-level approaches are the Flesch Reading Ease [

5] and Flesch–Kincaid readability score [

17], which estimate readability based on surface indicators such as orthographic (e.g., number of letters), syntactic (e.g., number of words), and phonological (e.g., number of syllables) features. In this framework, a higher score reflects greater difficulty. However, Yaneva et al. [

18] highlighted the limitations of these traditional metrics, arguing that Flesch-based scores are weak predictors of actual difficulty, as they fail to distinguish between easy and difficult content based on lexical features alone.

The emergence of neural language models has transformed the landscape of automatic text complexity assessment. Trained on large-scale corpora, these models can capture not only syntactic and semantic patterns but also elements of world knowledge, allowing for deeper interpretation of textual content. Modern readability estimation methods now frequently use Transformer-based architectures such as BERT and RoBERTa, which have superseded earlier neural models, like recurrent networks. For instance, Imperial [

19] proposed a hybrid model combining BERT embeddings with traditional linguistic features, achieving a notable 12.4% improvement in F1 score over classic readability metrics for English texts, and achieving robust performance on a low-resource language (i.e., Filipino). Similarly, Paraschiv et al. [

20] applied a BERT-based hybrid model within the ReaderBench framework to classify the difficulty of Russian-language textbooks by grade level, achieving an F1 score of 54.06%. The use of multilingual transformer models such as mBERT, XLM-R, and multilingual T5 has further expanded the applicability of these methods across languages. The ReadMe++ benchmark introduced by Naous et al. [

21] includes nearly 10,000 human-rated sentences across five languages—English, Arabic, French, Hindi, and Russian—spanning various domains. Their findings reveal that fine-tuned LLMs exhibit stronger correlations with human judgments than traditional scores such as Flesch–Kincaid and unsupervised LM-based baselines.

With the emergence of very large generative models like GPT-3 and GPT-4, another convenient method is to prompt the model to evaluate a text’s readability or generate a difficulty rating. In this approach, we consider the LLM as an expert evaluator: we feed it a passage and ask (in natural language) for an analysis of how easy or hard that passage would be for a certain reader group [

22,

23].

In addition, LLMs have also been employed for generating or rewriting texts at specified reading levels, mostly in English—an inverse but closely related task to readability evaluation [

24,

25]. The capacity to simplify a complex passage requires an underlying model of readability, as it requires the LLM to recognize what makes a text difficult and how to reduce that difficulty while preserving meaning. Huang et al. [

26] introduced the task of leveled-text generation, in which a model is given a source text and a target readability level (e.g., converting a 12th-grade passage to an 8th-grade level) and asked to rewrite the content accordingly. Evaluations of models such as GPT-3.5 and LLaMA-2 on a dataset of 100 educational texts, measured using metrics like the Lexile score, revealed that while the models could generally approximate the target level, human inspection identified notable issues, including occasional misinformation and inconsistent simplification across passages. In parallel, Rooein et al. [

27] introduced PROMPT-BASED metrics, an evaluation method that uses targeted yes/no questions to probe a model’s judgment of text difficulty. When integrated with traditional static metrics, this approach improved overall classification performance.

Further, Gobara et al. [

28] argued that instruction-tuned models show stronger alignment between user-specified difficulty levels and generated outputs, having a stronger influence than the model size. In contrast, Imperial and Tayyar Madabushi [

29] highlighted the limitations of proprietary models like ChatGPT (gpt-3.5-turbo and gpt-4-32k) for text simplification, showing that, without carefully crafted prompts, their outputs lagged behind open-source alternatives such as BLOOMZ and FlanT5 in both consistency and effectiveness.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to provide an exploration and evaluation of a state-of-the-art LLM, specifically GPT-4o, in assessing the complexity, judging the ease of understanding, and performing targeted simplification of Russian educational textbook texts. By analyzing the LLM’s performance across three distinct experimental setups using a curated corpus of Russian schoolbooks, we deepen the understanding of its potential utility and limitations within the Russian educational context. To accomplish these objectives, we examined three core research questions, each targeting a distinct aspect of LLM performance.

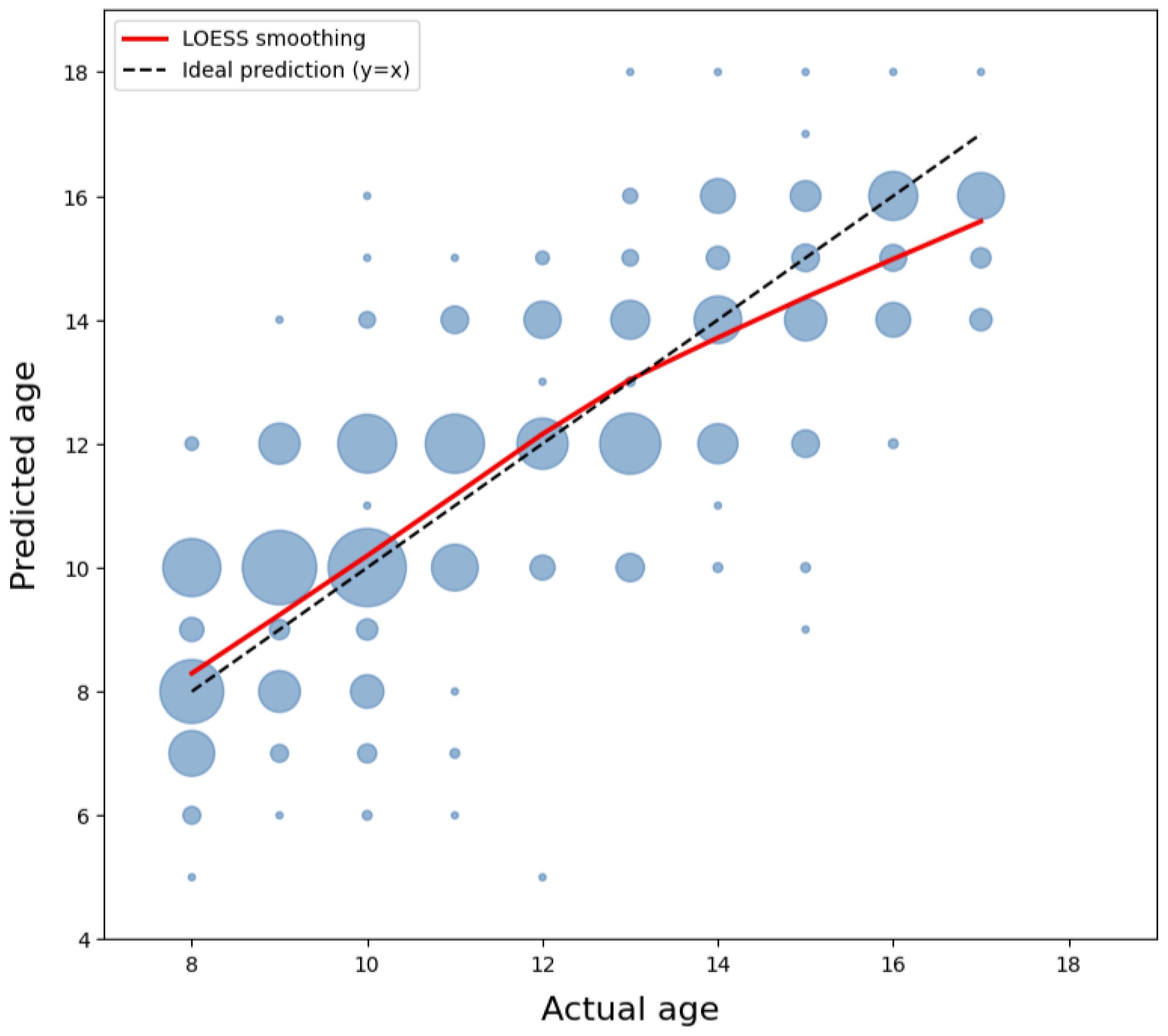

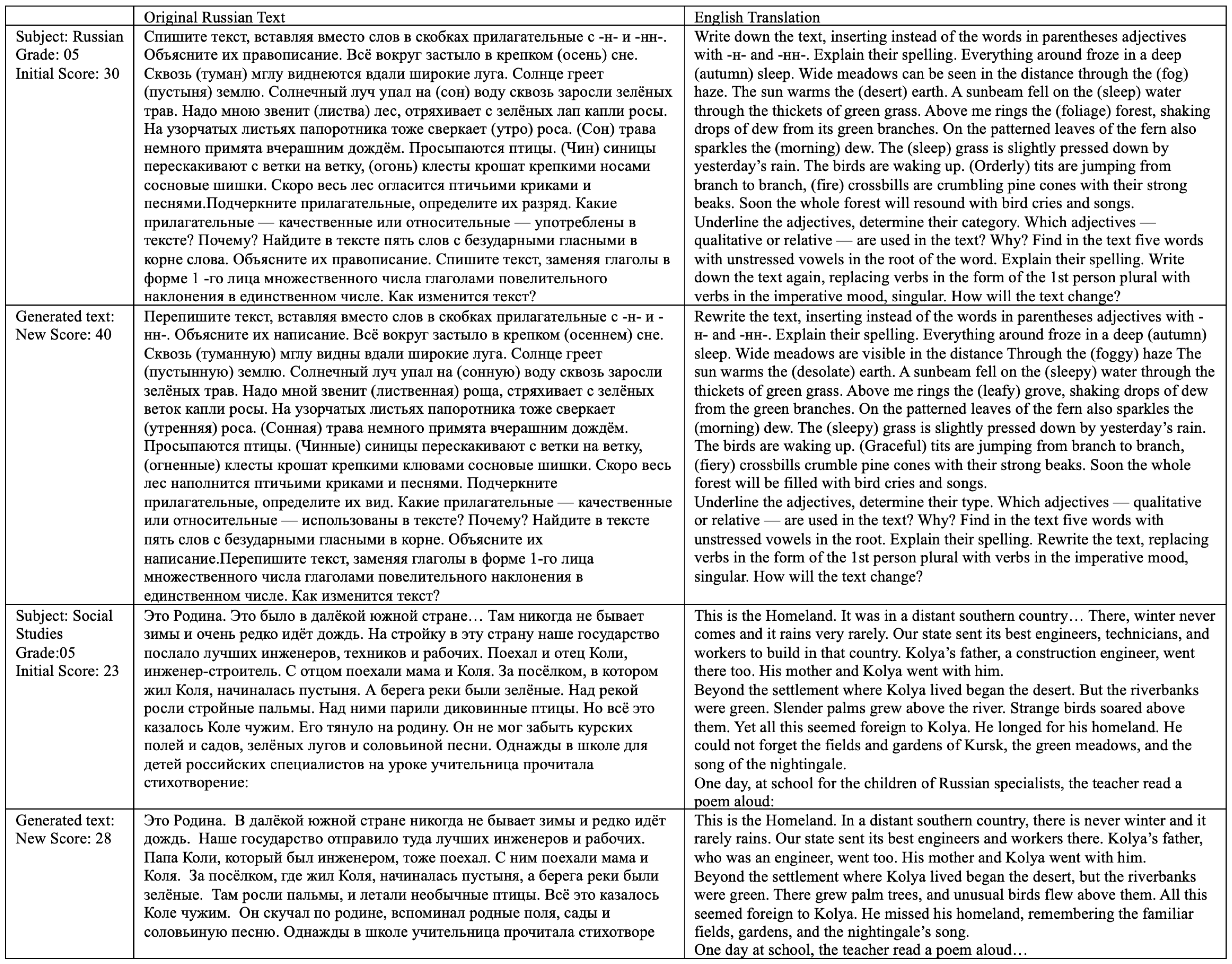

Our first research question investigated whether LLMs can correctly assess the complexity of Russian-language texts and, during this experiment, identify the key features that have influenced the decisions. The results from Experiment 1 (see

Table 3) show that the LLM adequately estimated the target age group, with a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) generally within 1 school year for most subjects. This suggests a fairly good capability to evaluate the difficulty of a textbook for the average Russian student.

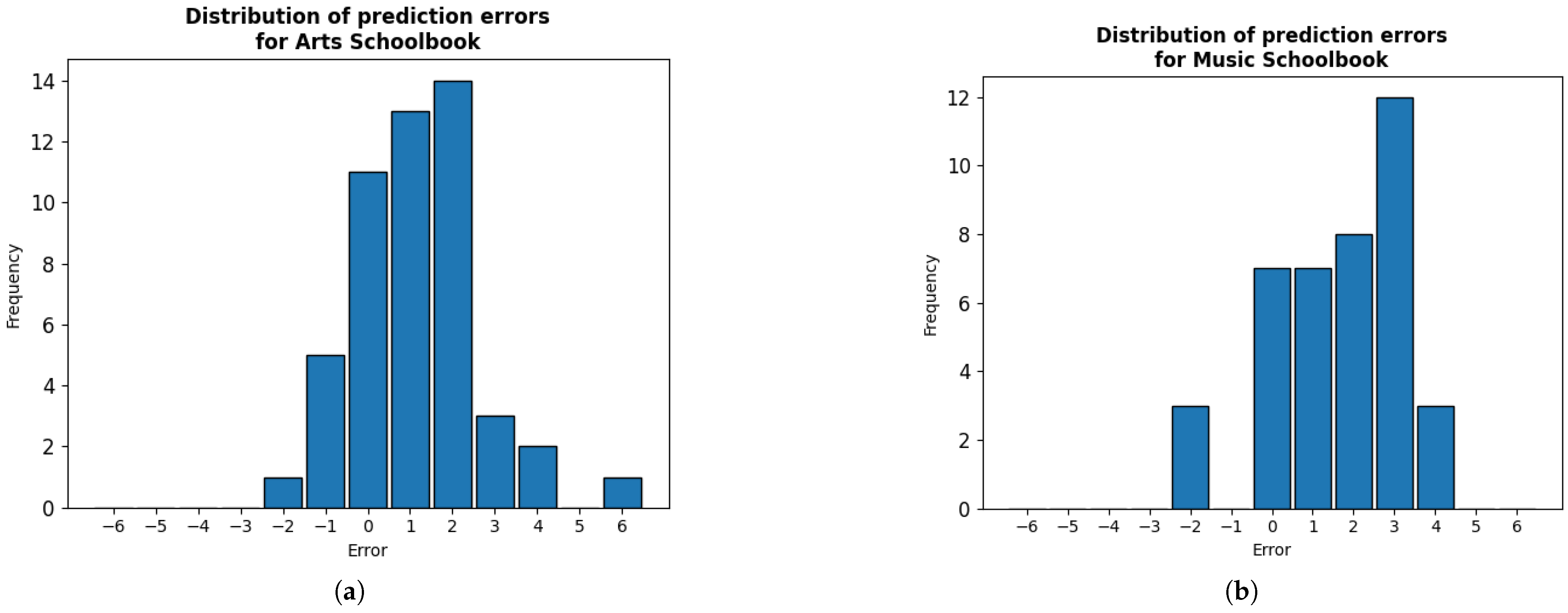

However, several important observations emerged. Firstly, we can notice a consistent trend across specific subjects, particularly Art, Informatics, Music, and Physics (see

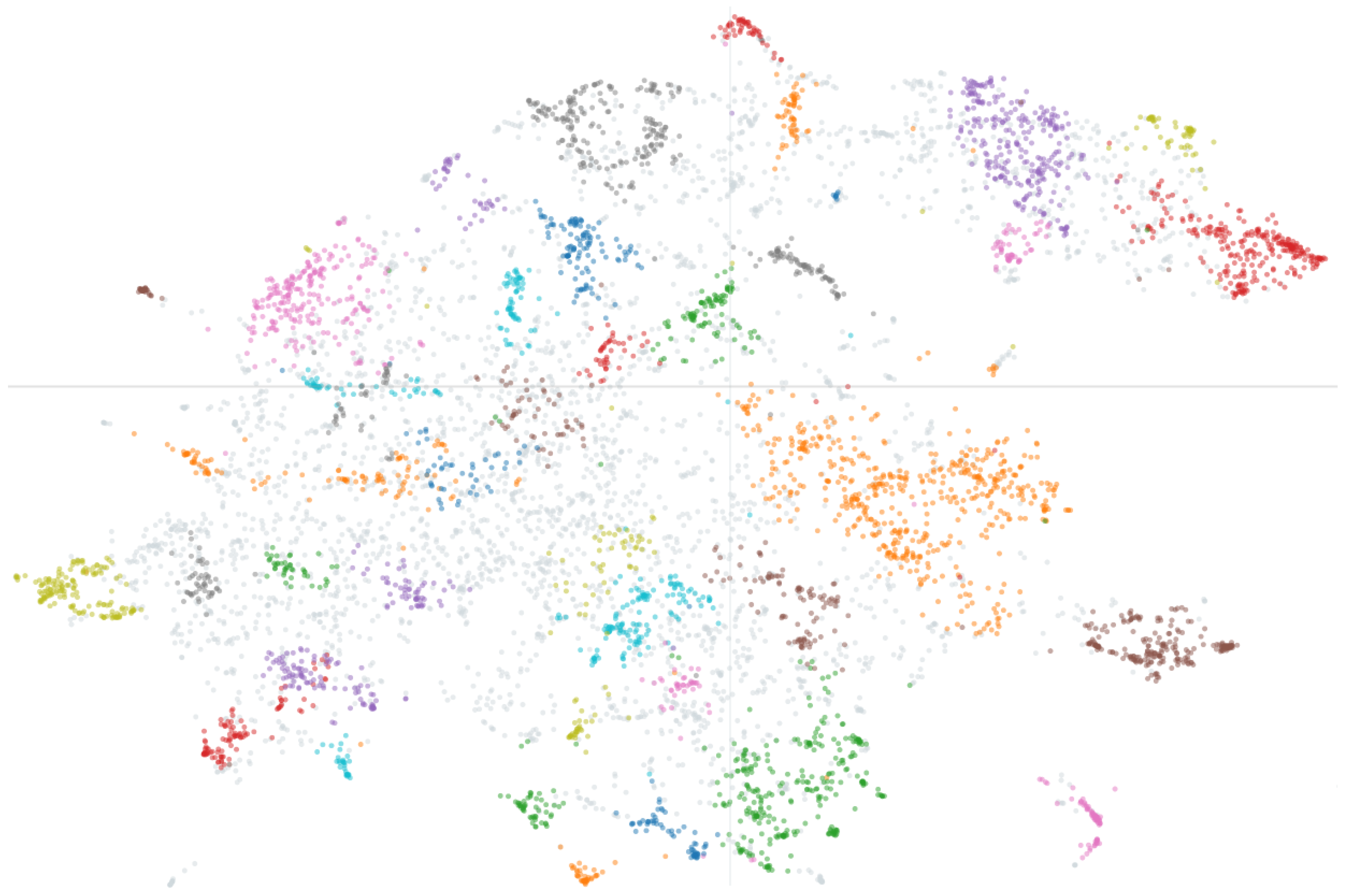

Figure 4). For these textbooks, the LLM tends to overestimate complexity, predicting a higher age level than the intended one. This bias might stem from the model overestimating factors such as challenging vocabulary, abstract concepts, or specific technical terminology encountered in these subjects. Analysis through the clustering of key phrases extracted by the LLM (see

Figure 6) supports this, indicating that the model’s decisions are influenced not merely by surface-level metrics (like sentence length or vocabulary used) but also by the addressed topics and domain-specific concepts that are discussed in the evaluated fragments.

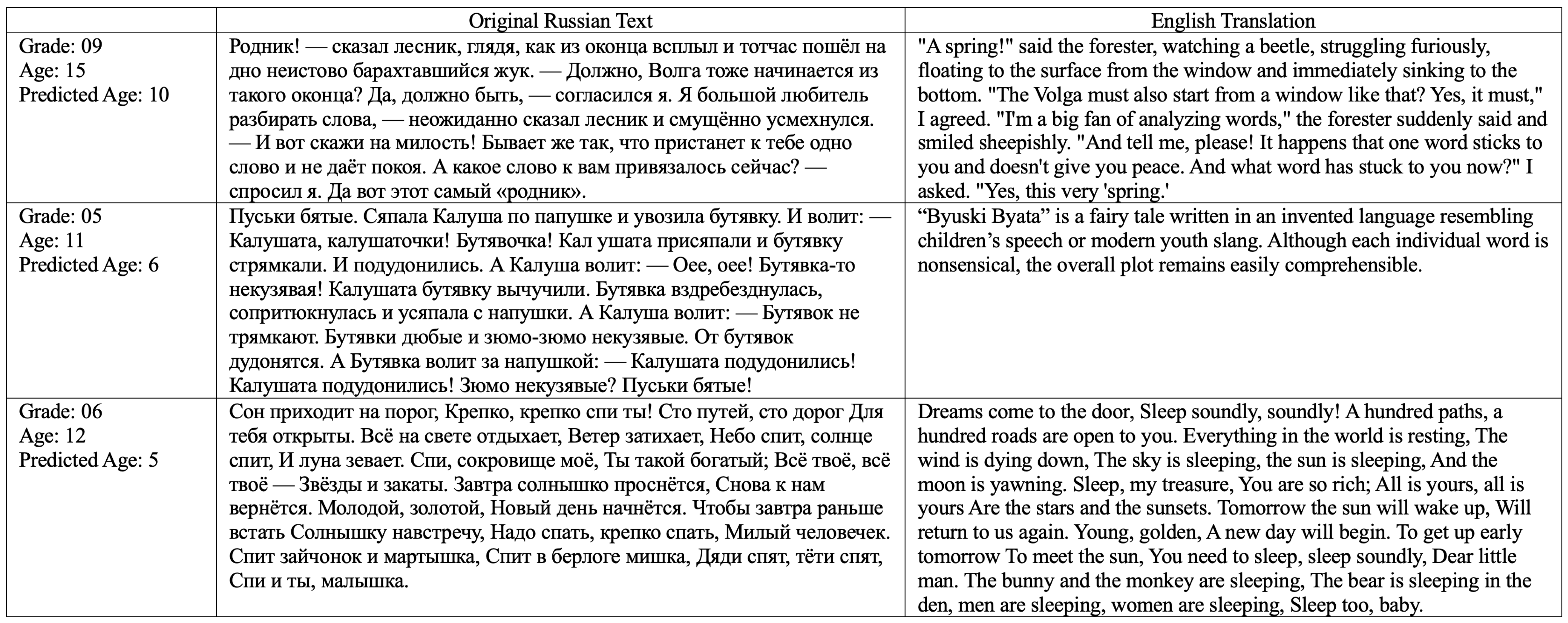

In addition, the analysis of extreme outliers, especially within the Russian-language subject (

Figure 5), highlighted an important limitation: the lack of context when evaluating a textbook fragment. Literary excerpts, when assessed in isolation as text segments, were often judged by the LLM to be far simpler than their intended target age. This occurred because the surrounding pedagogical context within the textbook (such as accompanying literary analysis tasks that significantly increased the effective cognitive load) was necessarily lost during the segmentation process required for analysis. This finding underscores that LLM assessments based on isolated text chunks may not accurately reflect the complexity a student encounters when interacting with the full material.

Furthermore, the model’s confidence, as measured by output token probabilities (see

Table 4 and

Table 8), did not always correlate with the accuracy. Even in cases of significant error (MAE > 2 years), the model often maintained high confidence, except notably in Geography, History, and Physics, where incorrect predictions were associated with lower confidence.

To conclude RQ1, while LLMs show considerable potential in assessing text complexity, their evaluations often display a bias toward overestimation. Notably, the model’s judgments appear to depend not only on linguistic features but also on the alignment of content themes with the cognitive and developmental expectations of the target age group. This thematic sensitivity, if properly understood and controlled, could serve as a valuable complement to traditional readability metrics. LLMs thus hold promise as valuable tools in augmenting classical methods of comprehension assessment. A promising direction for future research would be the development of techniques to disentangle purely linguistic signals from content- and theme-aware influences in the model’s predictions.

The second research question explored whether LLMs could serve as an effective proxy for student comprehension, simulating the extent to which the text is understandable. Results from Experiment 2 (see

Table 6) suggest a general alignment, with the LLM deeming the majority of fragments across most subjects as “comprehensible.” This indicates that the model can broadly distinguish between texts that are likely accessible and those that pose significant challenges.

However, subjects with lower comprehension ease included Russian, Informatics, Biology, and History. Analysis of the LLM’s rationale, by clustering its chain-of-thought conclusions, indicated that judgments of lower comprehension ease were often linked to a high terminological density, as well as challenges with complex language, abstract concepts, technical vocabulary, intricate instructions, or the perceived need for external guidance—factors that are highly relevant to actual student comprehension difficulties.

Interestingly, there was no direct one-to-one mapping between the age-prediction errors observed in Experiment 1 and the cognitive accessibility judgments in Experiment 2, suggesting that the LLM uses distinct pathways for these two tasks. Subjects in which the LLM significantly overestimated age (e.g., Art and Music) did not necessarily show lower comprehension ease. This suggests that the LLM might employ different internal weighting or criteria when assessing abstract “complexity” versus simulating direct “comprehension ease,” potentially separating linguistic difficulty from conceptual accessibility in its judgment process.

Our third research question assessed the LLM’s capability to successfully reduce text complexity to a specific target level, i.e., 3 school years lower across different subjects. The findings here present a mixed picture depending on the evaluation metric used.

When evaluated using a BERT-based grade-level classifier (see

Table 9), the LLM achieved very poor performance (14.88% accuracy), largely failing to align the generated text with the target grade. Many prediction errors matched the intended three-year gap exactly, indicating that the model often maintained complexity close to the original level rather than sufficiently simplifying the text.

Conversely, a statistically significant overall reduction in complexity was observed when evaluated using the Pushkin 100 readability score (see

Figure 9) (

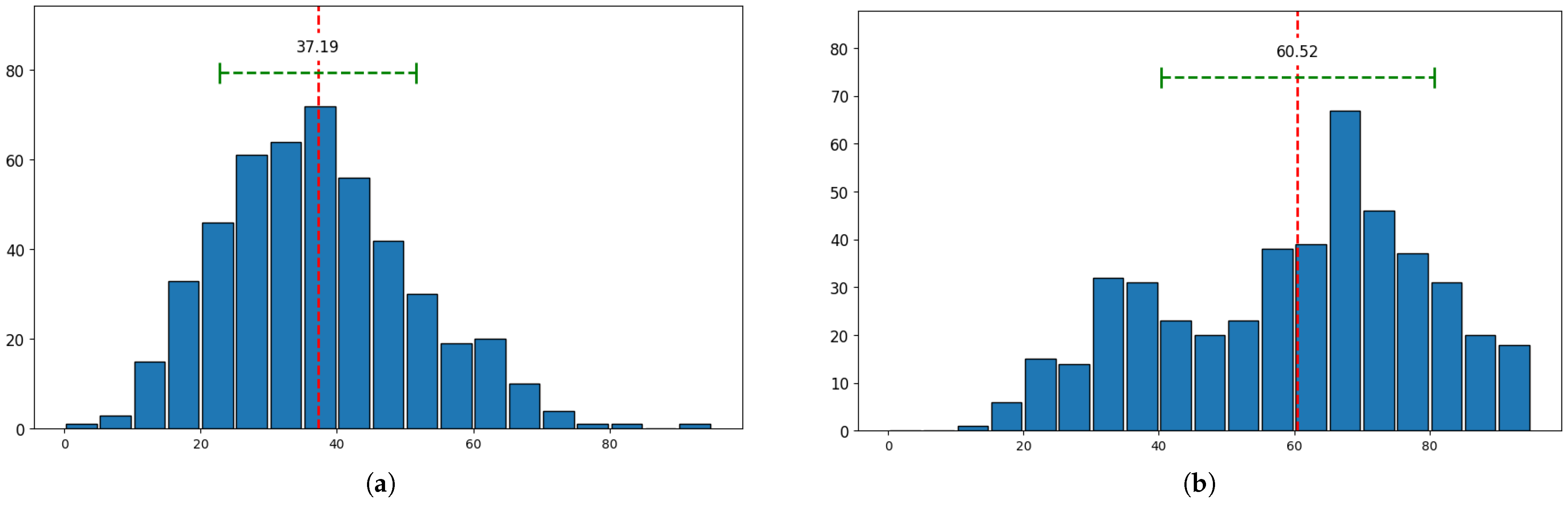

p < 0.001), evidenced by a clear leftward shift in the mean score distribution, from 60.52 to 37.19 (see

Figure 9). This reflects an average simplification of 23.33 points, corresponding to a decrease in estimated reading age from 14 to 10 years. Given that the Pushkin 100 score predicts comprehension across 2-year age intervals, the observed reduction closely aligns with our intended 3-grade simplification target.

Performance varied significantly across subjects, with Russian-language texts showing the least reduction according to the Pushkin 100 metric, potentially reflecting the inherent difficulty of simplifying literary texts while preserving essential meaning and style. Analysis of outliers where complexity increased (see

Figure 5 and

Figure 10) revealed these were often artifacts of the original task—e.g., the task of filling blanks in the Russian subject example steers the LLM to perform this task rather than simplifying it, or possibly metric sensitivity to minor changes in already simple texts (e.g., social studies). These outliers were deemed exceptions to the general trend of simplification.

Therefore, as a conclusion to RQ3, LLMs can contribute to text simplification, but achieving precise, controlled reduction to a specific pedagogical level (especially one defined by grade levels) remains a challenge that researchers can address. In addition, subject-specific consistent simplification outcomes remain an open research question that merits further exploration.

Practical and Ethical Implications

LLMs inherit and may amplify biases present in their training data, raising fairness concerns when applied to educational content assessment. These models have been shown to encode both explicit and implicit stereotypes—for example, prompts using male-associated names can provide more confident evaluations than those using female-associated names [

49]. Cultural and linguistic biases are also a concern. Many LLMs display Anglocentric biases that privilege Western or dominant-curriculum perspectives, which can marginalize content rooted in other languages, cultures, or educational systems [

50,

51,

52]. Such misalignment risks producing unfair assessments of materials that deviate from these norms, potentially disadvantaging learners in diverse cultural contexts.

Without deliberate safeguards, these biases can be perpetuated or even intensified by LLM-based tools. Notably, the findings of the present study reflect these broader concerns: even within a specific national context (e.g., Russian-language textbook analysis), the model exhibited some interpretations of textual content that align with known patterns of systemic bias.

Beyond these biases, LLMs face key technical limitations when used to evaluate or simplify academic content. Their assessments often rely on surface-level features—such as sentence length or vocabulary—without understanding the deeper conceptual or pedagogical context, leading to over- or underestimations of text complexity [

50]. Moreover, LLM-generated feedback lacks the intentionality of human instruction. Unlike educators who adapt explanations based on curriculum goals or student needs, LLMs tend to produce generic simplifications that may overlook important learning objectives or do not align with instructional intent [

53]. Thus, over-reliance on LLM-generated simplifications can diminish valuable learning opportunities [

54].

To realize the benefits of LLMs in education while minimizing risks, their use must be guided by responsible oversight. Educators should treat AI-generated outputs, such as readability ratings or summaries, as starting points, not final judgments, always adapting them to learner needs. Policymakers can support equitable adoption by promoting culturally inclusive AI tools and funding models trained on diverse curricula. As this study and others show, LLMs offer both promise and pitfalls, making ongoing research, human oversight, and strong ethical safeguards essential to ensuring their alignment with sound educational practice.