Empathy by Design: Reframing the Empathy Gap Between AI and Humans in Mental Health Chatbots

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Scope and Approach of This Critical Narrative Review

2. Review of Current Systems and Approaches

2.1. Early Chatbots and Contemporary Deployments

2.2. General-Purpose Large Language Models

2.3. Social Robots

3. Limitations of Current Approaches: Connectivity, Personalisation and Real-Time Adaptation

3.1. Shallow and Hollow Personalisation

3.2. Limited Memory and Context Length

3.3. Rigidity in Emotional Adaptation

3.4. Cloud Architectures

4. Future Directions: A Conceptual Framework for Adaptive Empathy

4.1. Building a Personal Profile for Each User

4.2. Adjusting Responses Dynamically Based on User Feedback

4.3. Potential for True Reinforcement Learning with Local Models

4.4. Exploring Adapter-Based Personalisation

4.5. Edge Architectures

4.6. Challenges and Risks

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Care Delivery

5.2. Felt Versus Performed Empathy

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioural Therapy |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| FAISS | Facebook AI Similarity Search |

| FDA | United States Food and Drug Administration |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| GPT | Generative Pretrained Transformer |

| LLaMA | Large Language Model Meta AI |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| LoRA | Low Rank Adaptation |

| MiniLMv2 | MiniLM version 2 |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| NICE | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| RAG | Retrieval Augmented Generation |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RLHF | Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback |

| SDK | Software Development Kit |

| SFT | Supervised Fine-Tuning |

| UK | United Kingdom |

References

- Powell, P.A.; Roberts, J. Situational determinants of cognitive, affective, and compassionate empathy in naturalistic digital interactions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J. Empathy in medicine, what it is, and how much we really need it. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derksen, F.; Bensing, J.; Lagro-Janssen, A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice, a systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e76–e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nembhard, I.M.; David, G.; Ezzeddine, I.; Betts, D.; Radin, J. A systematic review of research on empathy in health care. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 58, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, P.; Timothy, A.; McClintock, A.S. Empathy from the client’s perspective, a grounded theory analysis. Psychother. Res. 2017, 27, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, R.; Bohart, A.C.; Watson, J.C.; Murphy, D. Therapist empathy and client outcome, an updated meta-analysis. Psychotherapy 2018, 55, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, C.; Southward, M.W.; Altenburger, E.M.; Howard, K.P.; Cheavens, J.S. The within-person effects of validation and invalidation on in-session changes in affect. Personal. Disord. 2019, 10, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyers, T.B.; Miller, W.R. Is low therapist empathy toxic? Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2013, 27, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brännström, A.; Wester, J.; Nieves, J.C. A formal understanding of computational empathy in interactive agents. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2024, 85, 101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Luo, J. Toward artificial empathy for human-centered design. J. Mech. Des. 2023, 146, 061401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McStay, A. Replika in the Metaverse, the moral problem with empathy in “It from Bit”. AI Ethics 2023, 3, 1433–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbic. Limbic for Talking Therapies. 2025. Available online: https://www.limbic.ai/nhs-talking-therapies (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Malgaroli, M.; Schultebraucks, K.; Myrick, K.J.; Andrade Loch, A.; Ospina-Pinillos, L.; Choudhury, T.; Kotov, R.; De Choudhury, M.; Torous, J. Large language models for the mental health community, framework for translating code to care. Lancet Digit. Health 2025, 7, e282–e285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howcroft, A.; Hopkins, G. Exploring Mars, an immersive survival game for planetary education. In Proceedings of the 18th European Conference on Games Based Learning, Aarhus, Denmark, 3–4 October 2024; Academic Conferences International Limited: Reading, UK, 2024; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, H.; Song, H.; Baek, G.; Shin, M.; Jung, C.; Cha, M.; Choi, J.; Cha, C. The potential of chatbots for emotional support and promoting mental well-being in different cultures, mixed methods study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e51712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Gao, J.; Li, D.; Shum, H.Y. The design and implementation of XiaoIce, an empathetic social chatbot. Comput. Linguist. 2020, 46, 53–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Topol Review. Preparing the Healthcare Workforce to Deliver the Digital Future; Health Education England: Leeds, UK, 2019. Available online: https://topol.digitalacademy.nhs.uk/the-topol-review (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Reynolds, K.; Nadelman, D.; Durgin, J.; Ansah-Addo, S.; Cole, D.; Fayne, R.; Harrell, J.; Ratycz, M.; Runge, M.; Shepard-Hayes, A.; et al. Comparing the quality of ChatGPT- and physician-generated responses to patients’ dermatology questions in the electronic medical record. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 49, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wang, A.; Strachan, P.; Séguin, J.A.; Lachgar, S.; Schroeder, K.C.; Fleck, M.S.; Wong, R.; Karthikesalingam, A.; Natarajan, V.; et al. Conversational AI in health, design considerations from a Wizard-of-Oz dermatology case study with users, clinicians and a medical LLM. In Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2024; p. 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Giorgi, S.; Aich, A.; Lahnala, A.; Curtis, B.; Ungar, L.; Sedoc, J. The illusion of empathy, how AI chatbots shape conversation perception. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 14327–14336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholich, T.; Barr, M.; Wiltsey Stirman, S.; Raj, S. A comparison of responses from human therapists and large language model–based chatbots to assess therapeutic communication, mixed methods study. JMIR Ment. Health 2025, 12, e69709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohny, H. Reframing “dehumanisation”, AI and the reality of clinical communication. J. Med. Ethics 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, N. AI’s empathy gap, the risks of conversational artificial intelligence for young children’s well-being and key ethical considerations for early childhood education and care. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2023, 26, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howcroft, A.; Bennett Weston, A.; Khan, A.; Griffiths, J.; Gay, S.; Howick, J. AI chatbots versus human healthcare professionals, a systematic review and meta-analysis of empathy in patient care. Br. Med. Bull. 2025, 156, ldaf017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, K.; Sommer, N.R.; Mortillaro, M. Large language models are proficient in solving and creating emotional intelligence tests. Commun. Psychol. 2025, 3, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, D.; Schuller, B.W. The age of artificial emotional intelligence. Computer 2018, 51, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhera, J. Narrative reviews, flexible, rigorous, and practical. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coheur, L. From Eliza to Siri and Beyond. In Proceedings of the Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems (IPMU 2020), Proceedings Part I, Lisbon, Portugal, 15–19 June 2020; Lecture Notes in Computer Science, LNCS 1237. pp. 29–41, ISBN 978-3-030-50145-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K.K.; Darcy, A.; Vierhile, M. Delivering cognitive behavior therapy to young adults with symptoms of depression and anxiety using a fully automated conversational agent (Woebot), a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment. Health 2017, 4, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheu, M.M. AI Psychotherapy Shutdown, What Woebot’s Exit Signals For Clinicians. Telehealth.org, 19 August 2025. Available online: https://telehealth.org/blog/ai-psychotherapy-shutdown-what-woebots-exit-signals-for-clinicians/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- NICE. Digital Front Door Technologies to Gather Service User Information for NHS Talking Therapies for Anxiety and Depression Assessments, Early Value Assessment (HTE30). 24 July 2025. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/hte30 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Beatty, C.; Malik, T.; Meheli, S.; Sinha, C. Evaluating the therapeutic alliance with a free-text CBT conversational agent (Wysa), a mixed-methods study. Front. Digit. Health 2022, 4, 847991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysa. FAQs. 2025. Available online: https://www.wysa.com/faq (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Phang, J.; Lampe, M.; Ahmad, L.; Agarwal, S.; Fang, C.M.; Liu, A.R.; Danry, V.; Lee, E.; Chan, S.W.; Pataranutaporn, P. Investigating affective use and emotional well-being on ChatGPT. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.03888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisuzzaman, D.M.; Malins, J.G.; Friedman, P.A.; Attia, Z.I. Fine-tuning large language models for specialized use cases. Mayo Clin. Proc. Digit. Health 2025, 3, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, W.R.; Wiesenfeld, B.; Brandfield-Harvey, B.; Jonassen, Z.; Mandal, S.; Stevens, E.R.; Major, V.J.; Lostraglio, E.; Szerencsy, A.; Jones, S.; et al. Large Language Model-Based Responses to Patients’ In-Basket Messages. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2422399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tanco, K.; Rhondali, W.; Perez-Cruz, P.; Tanzi, S.; Chisholm, G.B.; Baile, W.; Frisbee-Hume, S.; Williams, J.; Masino, C.; Cantu, H.; et al. Patient perception of physician compassion after a more optimistic vs a less optimistic message, a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J.W.; Poliak, A.; Dredze, M.; Leas, E.C.; Zhu, Z.; Kelley, J.B.; Faix, D.J.; Goodman, A.M.; Longhurst, C.A.; Hogarth, M.; et al. Comparing physician and artificial intelligence chatbot responses to patient questions posted to a public social media forum. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, T.; Luger, T.; Volkman, J.; Rocheleau, M.; Mueller, N.; Barker, A.; Nazi, K.; Houston, T.; Bokhour, B. Patient centeredness in electronic communication, evaluation of patient-to-health care team secure messaging. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, K.A.; Ospina, N.S.; Montori, V.M. Physicians interrupting patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaak, S.; Mantler, E.; Szeto, A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare, barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2017, 30, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papneja, H.; Yadav, N. Self-disclosure to conversational AI, a literature review, emergent framework, and directions for future research. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2025, 29, 119–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnepper, R.; Roemmel, N.; Schaefert, R.; Lambrecht-Walzinger, L.; Meinlschmidt, G. Exploring biases of large language models in the field of mental health, comparative questionnaire study of the effect of gender and sexual orientation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa case vignettes. JMIR Ment. Health 2025, 12, e57986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blavette, L.; Dacunha, S.; Alameda-Pineda, X.; Hernández García, D.; Gannot, S.; Gras, F.; Gunson, N.; Lemaignan, S.; Polic, M.; Tandeitnik, P.; et al. Acceptability and usability of a socially assistive robot integrated with a large language model for enhanced human-robot interaction in a geriatric care institution, mixed methods evaluation. JMIR Hum. Factors 2025, 12, e76496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laban, G.; Morrison, V.; Kappas, A.; Cross, E.S. Coping with emotional distress via self-disclosure to robots, an intervention with caregivers. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2025, 17, 1837–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.D.R.; Rubya, S. An overview of chatbot-based mobile mental health apps, insights from app description and user reviews. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2023, 11, e44838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, E. Sam Altman Says GPT-5’s “Personality” Will Get a Revamp, But It Will Not Be as “Annoying” as GPT-4o. Business Insider. 2025. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/sam-altman-openai-gpt5-personality-update-gpt4o-return-backlash-2025-8 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Hornstein, S.; Zantvoort, K.; Lueken, U.; Funk, B.; Hilbert, K. Personalization strategies in digital mental health interventions, a systematic review and conceptual framework for depressive symptoms. Front. Digit. Health 2023, 5, 1170002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthropic. Claude 3.5 Sonnet. 2024. Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-3-5-sonnet (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- OpenAI. What Is Memory? 2025. Available online: https://help.openai.com/en/articles/8983136-what-is-memory (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Kang, D.; Kim, S.; Kwon, T.; Moon, S.; Cho, H.; Yu, Y.; Lee, D.; Yeo, J. Can large language models be good emotional supporter? Mitigating preference bias on emotional support conversation. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; pp. 15232–15261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.; Tng, G.Y.Q.; Hartanto, A. Potential and pitfalls of mobile mental health apps in traditional treatment, an umbrella review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojat, M.; Louis, D.Z.; Maxwell, K.; Markham, F.; Wender, R.; Gonnella, J.S. Patient perceptions of physician empathy, satisfaction with physician, interpersonal trust, and compliance. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2010, 1, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biringer, E.; Hartveit, M.; Sundfør, B.; Ruud, T.; Borg, M. Continuity of care as experienced by mental health service users, a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Bao, H.; Huang, S.; Dong, L.; Wei, F. MiniLMv2, multi-head self-attention relation distillation for compressing pretrained transformers. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 2140–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, E.; Mesut, A. Performance Analysis of Chroma, Qdrant, and Faiss Databases; Technical University of Gabrovo: Gabrovo, Bulgaria, 2024; Available online: https://unitechsp.tugab.bg/images/2024/4-CST/s4_p72_v3.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Pan, J.J.; Wang, J.; Li, G. Survey of vector database management systems. VLDB J. 2024, 33, 1591–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisten, L.M.; Findling, F.; Bellinghausen, J.; Kinateder, M.; Probst, T.; Lion, D.; Shiban, Y. The effect of non-lexical verbal signals on the perceived authenticity, empathy and understanding of a listener. Eur. J. Couns. Psychol. 2021, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.; Scherer, S.; DeVault, D.; Gratch, J.; Artstein, R.; Hartholt, A.; Lucas, G.; Marsella, S.; Morbini, F.; Nazarian, A.; et al. Detection and computational analysis of psychological signals using a virtual human interviewing agent. J. Pain Manag. 2016, 9, 311–321. [Google Scholar]

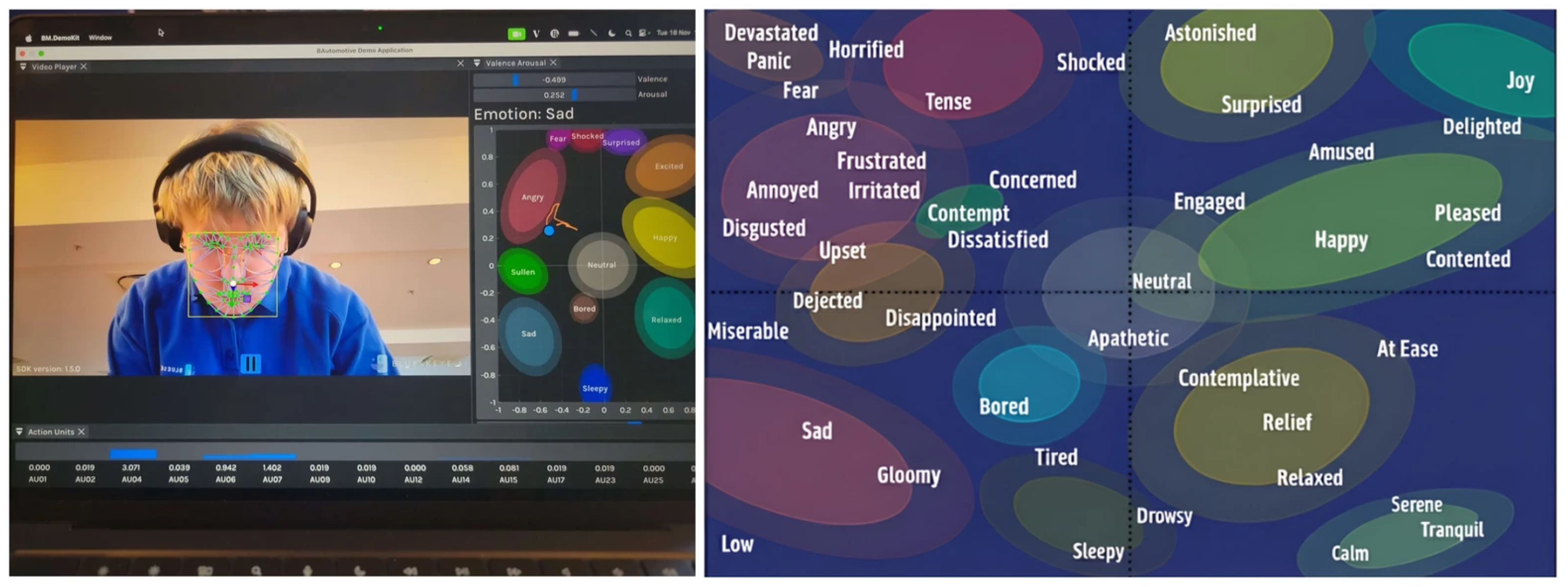

- Baltrusaitis, T.; Zadeh, A.; Lim, Y.C.; Morency, L.-P. OpenFace 2.0: Facial Behavior Analysis Toolkit. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2018), Xi’an, China, 15–19 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BLUESKEYE AI. Health and Well-Being. 2025. Available online: https://www.blueskeye.com/health-well-being (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA, low-rank adaptation of large language models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Online, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Layla Network. Meet Layla. 2025. Available online: https://www.layla-network.ai (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Geroimenko, V. Generative AI hallucinations in healthcare, a challenge for prompt engineering and creativity. In Human-Computer Creativity: Generative AI in Education, Art, and Healthcare; Geroimenko, V., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerken, T. Update That Made ChatGPT “Dangerously” Sycophantic Pulled. BBC News. 2025. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cn4jnwdvg9qo (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Østergaard, S.D. Will generative artificial intelligence chatbots generate delusions in individuals prone to psychosis? Schizophr. Bull. 2023, 49, 1418–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzen, C. Ex-OpenAI CEO and Power Users Sound Alarm over AI Sycophancy and Flattery of Users. VentureBeat. 2025. Available online: https://venturebeat.com/ai/ex-openai-ceo-and-power-users-sound-alarm-over-ai-sycophancy-and-flattery-of-users (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Purtill, J. Replika Users Fell in Love with Their AI Chatbot Companions. Then They Lost Them. ABC News. 2023. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2023-03-01/replika-users-fell-in-love-with-their-ai-chatbot-companion/102028196 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Brooks Holliday, S.; Matthews, S.; Bialas, A.; McBain, R.K.; Cantor, J.H.; Eberhart, N.; Breslau, J. A qualitative investigation of preparedness for the launch of 988, implications for the continuum of emergency mental health care. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2023, 50, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalao, R.; Broadbent, M.; Ashworth, M.; Das-Munshi, J.; Schofield, L.H.; Hotopf, M.; Dorrington, S. Access to psychological therapies amongst patients with a mental health diagnosis in primary care, a data linkage study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 60, 2149–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montemayor, C.; Halpern, J.; Fairweather, A. In principle obstacles for empathic AI, why we cannot replace human empathy in healthcare. AI Soc. 2022, 37, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, E.B.; Yao, X. Clinical empathy as emotional labor in the patient–physician relationship. JAMA 2005, 293, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, A.; Hui, L.; Oleynikov, C.; Boamah, S. Compassion fatigue in healthcare providers, a scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, A.M.; Suryana, D.; Kamarudin, E.M.E.; Naidu, N.B.M.; Kamsani, S.R.; Govindasamy, P. Compassion fatigue in helping professions, a scoping literature review. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. Ethical Guidance for AI in the Professional Practice of Health Service Psychology. 2025. Available online: https://www.apa.org/topics/artificial-intelligence-machine-learning/ethical-guidance-ai-professional-practice (accessed on 17 September 2025).

| Dimension | Rule-Based AI Chatbot | Typical Generative AI Chatbot (LLMs) | Human Practitioner (“Idealised” Standard) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Determinism/Coherence | Deterministic, highly predictable replies | Coherent and natural-sounding; capable of nuanced dialogue | Adapts how they speak based on the person and situation |

| Perceived empathy | Very generic, scripted empathy | Often perceived as empathic, but can feel “hollow” or superficial | Deep, context-sensitive empathy; can read non-verbal cues |

| Availability | Continuous 24/7 access, barring server outages or maintenance. | Continuous 24/7 access, barring server outages or maintenance | Scheduled through dedicated appointments, though availability is often constrained by waiting lists and high workloads, potentially resulting in brief or brusque replies |

| Scope/Flexibility | Inflexible responses; works best in narrow, pre-defined scenarios | Detailed replies; broad conversational scope across many topics | High flexibility; can work across complex, messy, and ambiguous real-world problems |

| Memory/Continuity | Little or no memory of past conversations | Memory within a session; typically forgets across sessions | Can remember personal history and build rapport over time |

| Safety/Reliability | Safer because behaviour is tightly constrained and predictable | Risk of errors and hallucinations; needs guardrails | Professionally trained and regulated, but still subject to time pressure and errors |

| Judgement/Bias | Low sense of “judgement”, though design choices can add bias | Reduced overt judgement, but may reflect training-data biases | Strives for a non-judgemental stance, though susceptible to passing judgement (even if unconscious) potentially leading to less empathy and dismissive attitudes |

| Privacy/Deployment | Often local or on tightly controlled systems | Usually cloud-based; raises privacy and data-sharing concerns; on-device (edge) options are emerging | Bound by strict professional and legal duties of confidentiality |

| Overall Quality/Consistency | Consistent but rigid; quality is steady but extremely limited | Quality varies with prompts, model, and safeguards; can sometimes exceed humans in rated perceived empathy | Variable between practitioners and moment-to-moment (fatigue, workload, emotional state, and emotion-type differences—e.g., easier to empathise with grief than anger) |

| Standard Generative AI | Retrieval-Augmented Generation | |

|---|---|---|

| User Input | “I freak out and panic I’m gonna get fired [when scores aren’t the greatest].” | “I freak out and panic I’m gonna get fired [when scores aren’t the greatest].” |

| Internal Logic | Detects topic: “Job Security/Anxiety”. Generates generic supportive advice. | Retrieves Memory: “User received ‘Top Performer’ bonus last month”. |

| Response | “It’s understandable to feel anxious when metrics seem tied to your security, and many people notice their worry spike when scores dip. It can help to look at longer-term trends instead of any single week and remind yourself that consistency tends to matter more than brief fluctuations. Grounding techniques or a short reset break can also help steady things when the panic starts to rise.” | “Let’s pause and look at what’s real here. You earned a top-tier bonus just last month, which is strong evidence that your company recognizes your performance and values what you bring. With that in mind, does this week reflect an actual issue the company is concerned about, or is it more likely a normal dip that feels bigger because you hold yourself to a high standard and care about doing well?” |

| Potential User Impact | Generic: User feels patronised with basic advice. | Personal: User feels validated by their own track record. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Howcroft, A.; Blake, H. Empathy by Design: Reframing the Empathy Gap Between AI and Humans in Mental Health Chatbots. Information 2025, 16, 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121074

Howcroft A, Blake H. Empathy by Design: Reframing the Empathy Gap Between AI and Humans in Mental Health Chatbots. Information. 2025; 16(12):1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121074

Chicago/Turabian StyleHowcroft, Alastair, and Holly Blake. 2025. "Empathy by Design: Reframing the Empathy Gap Between AI and Humans in Mental Health Chatbots" Information 16, no. 12: 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121074

APA StyleHowcroft, A., & Blake, H. (2025). Empathy by Design: Reframing the Empathy Gap Between AI and Humans in Mental Health Chatbots. Information, 16(12), 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121074