Trustworthy Data Space Collaborative Trust Mechanism Driven by Blockchain: Technology Integration, Cross-Border Governance, and Standardization Path

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- There is a risk of sensitivity exposure in cross-domain circulation (i.e., when data circulates in an environment with multiple parties and a lack of mutual trust, there is a lack of end-to-end verifiable access control and a minimum disclosure mechanism) [9];

- (2)

- There are challenges in usability verification under the heterogeneity of master data sovereignty. Due to differences in laws in different countries and regions, it is difficult to make verifiable judgments on data processing activities without relying on centralized approval [10];

- (3)

- There is difficulty in automating the allocation of stakeholder value. The data value chain involves multiple heterogeneous stakeholders such as platform operators, data providers, data users, and regulatory agencies [11];

- (4)

- Data island barriers exist in heterogeneous environments. In multi-chain architectures, multi-cloud environments, and cross-industry application scenarios, there is a lack of universal data format standards and interface protocols [12];

- (5)

- There are performance-privacy-cost trade-offs in high-concurrency scenarios. In large-scale concurrent data transaction scenarios, all three have inherent constraints that may significantly reduce the efficiency of multi-party collaboration and affect overall system performance [13].

- Comprehensively review the development of trustworthy data spaces, systematically reviewing related technologies and the latest research progress;

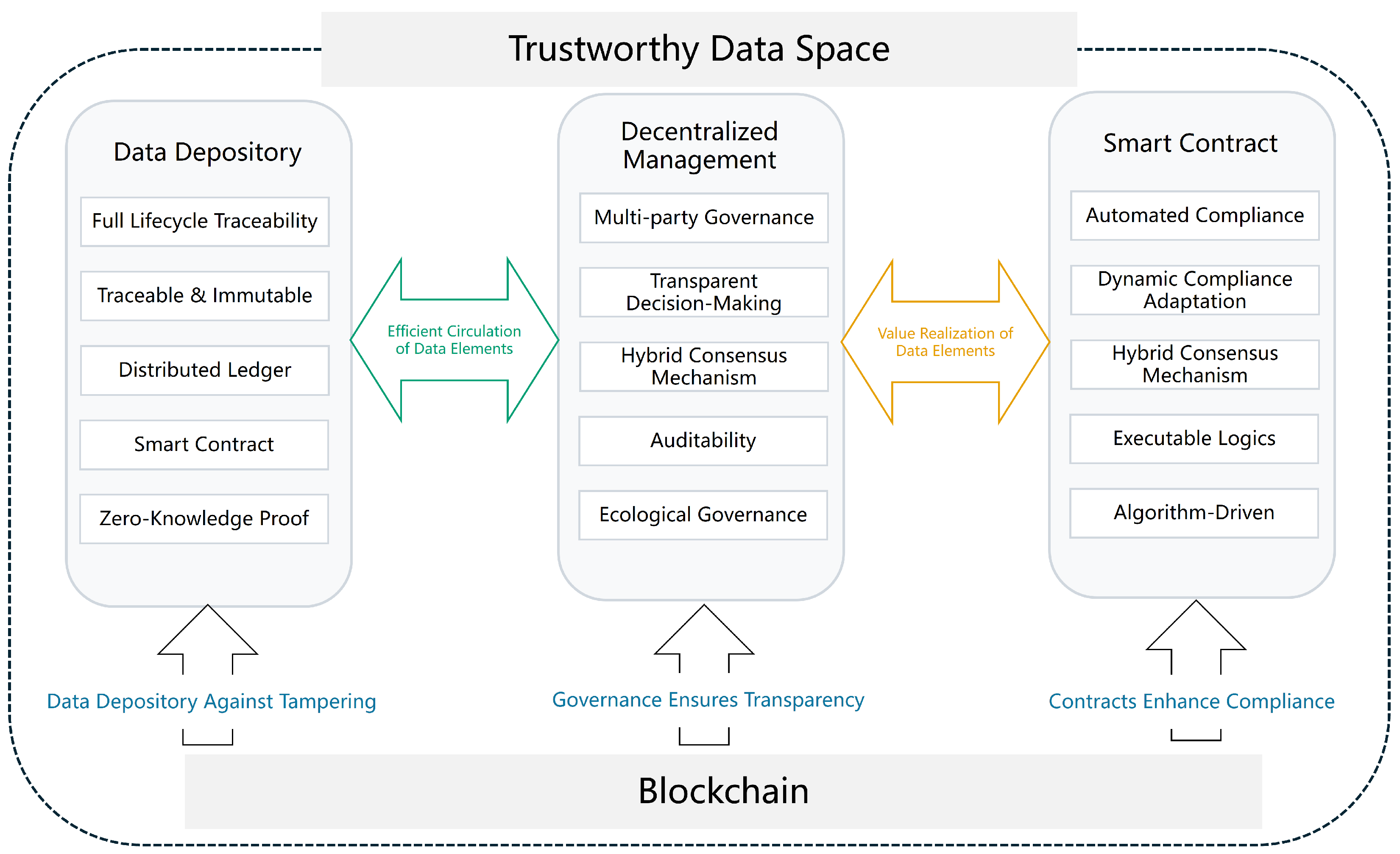

- Demonstrate the scientific validity of blockchain-enabled trustworthy data spaces, proposing an overall technical framework of “technology convergence, cross-border governance, and standardization path” (TGS) as well as a collaborative trust technology verification scheme of “on-chain light attest, off-chain deep store, and cross-layer verifiable bridge” (LPHS-XV);

- Conduct an empirical evaluation of the LPHS-XV framework based on real-world application cases to verify its effectiveness and feasibility.

2. Related Works

2.1. Trustworthy Data Space

2.2. Blockchain

2.3. Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP)

- (1)

- Completeness: If the claim is true, then an honest prover who follows the protocol will eventually convince an honest verifier to accept the claim. For a true proposition, a correctly implemented protocol will not cause a reliable verifier to mistakenly judge it as false.

- (2)

- Reliability: If the claim is false, then no matter how the prover cheats, it is almost impossible to make the honest verifier accept the false claim. By designing a soundness error, the probability of successful cheating can be quickly reduced to a negligible level under repeated execution of the protocol.

- (3)

- Zero knowledge: If the claim is true, then the verifier will not obtain any additional information about the secret during the verification process except the conclusion that the claim is true. The verifier cannot learn the secret itself afterward, nor can it use the details of the proof to persuade a third party of the claim.

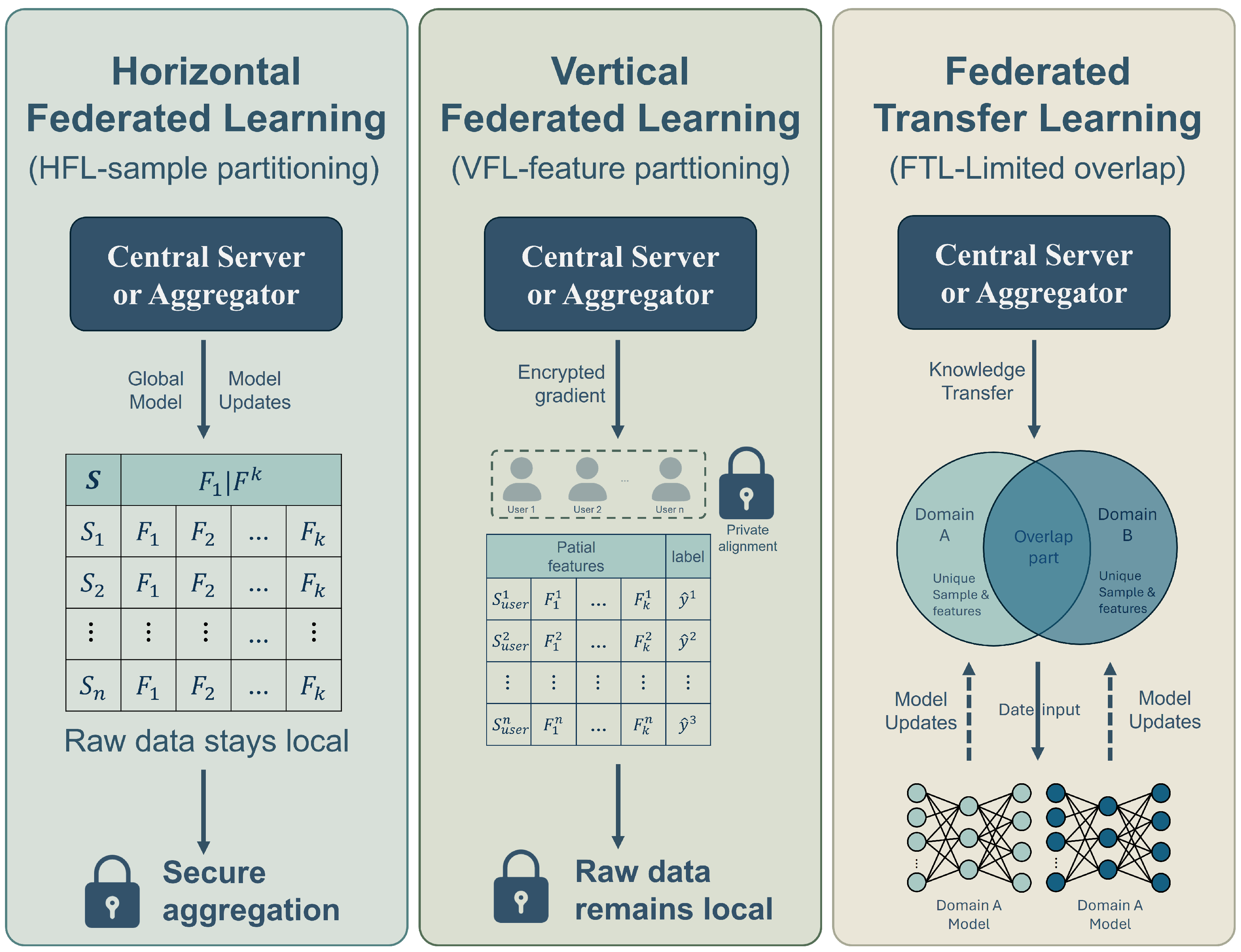

2.4. Federated Learning

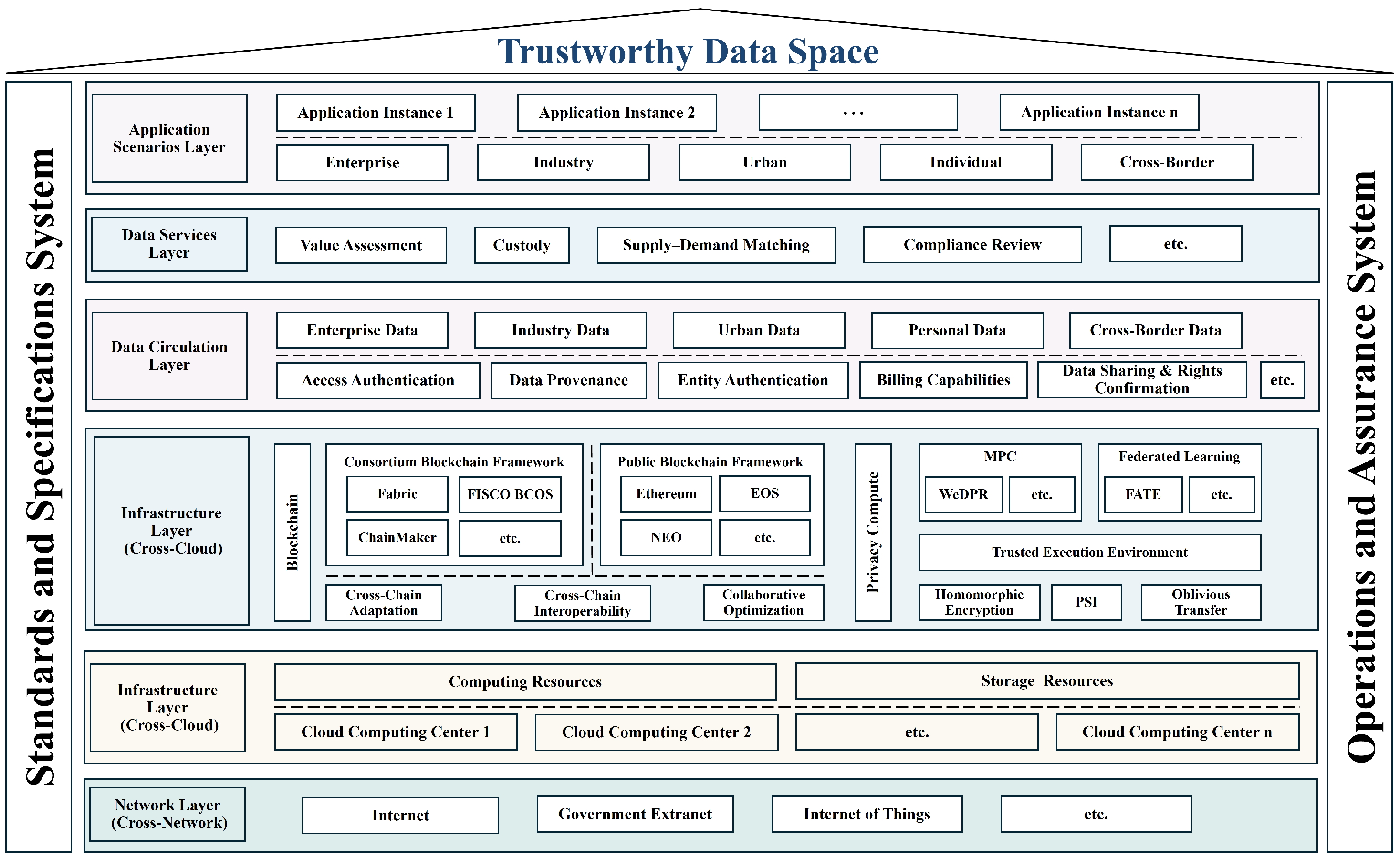

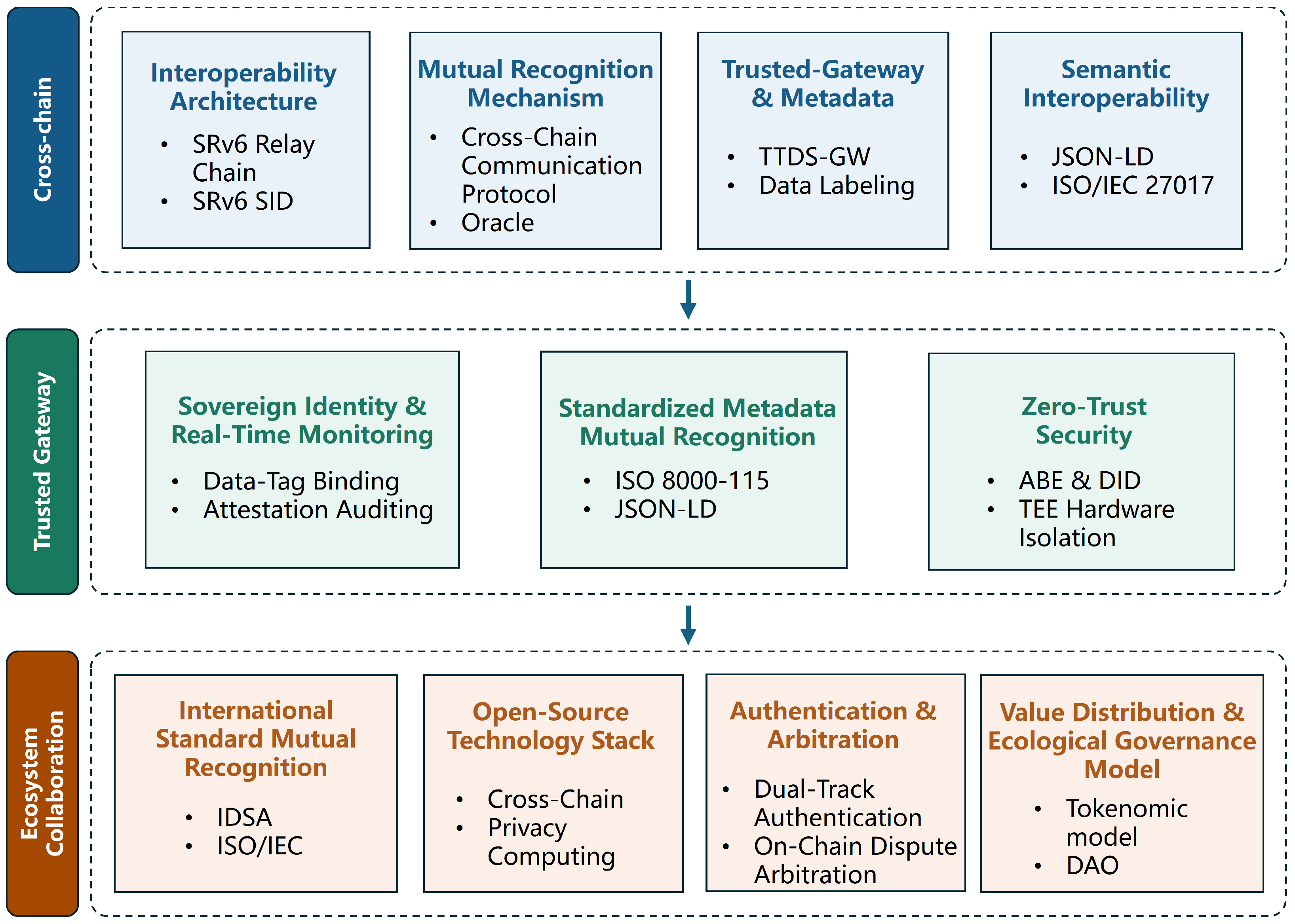

3. Framework of Technology-Governance-Standardization (TGS)

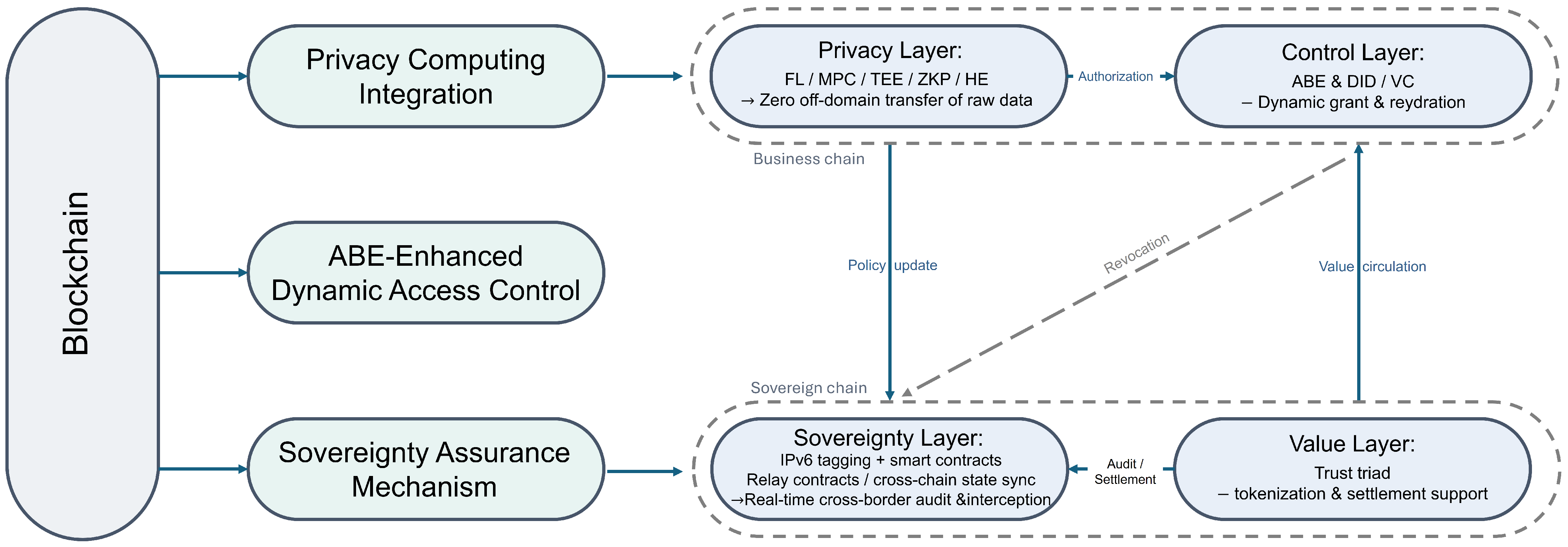

3.1. Technology Integration

3.1.1. Ensuring Data Privacy and Controllable Circulation

3.1.2. Cross-Domain Operation and Circulation Realization

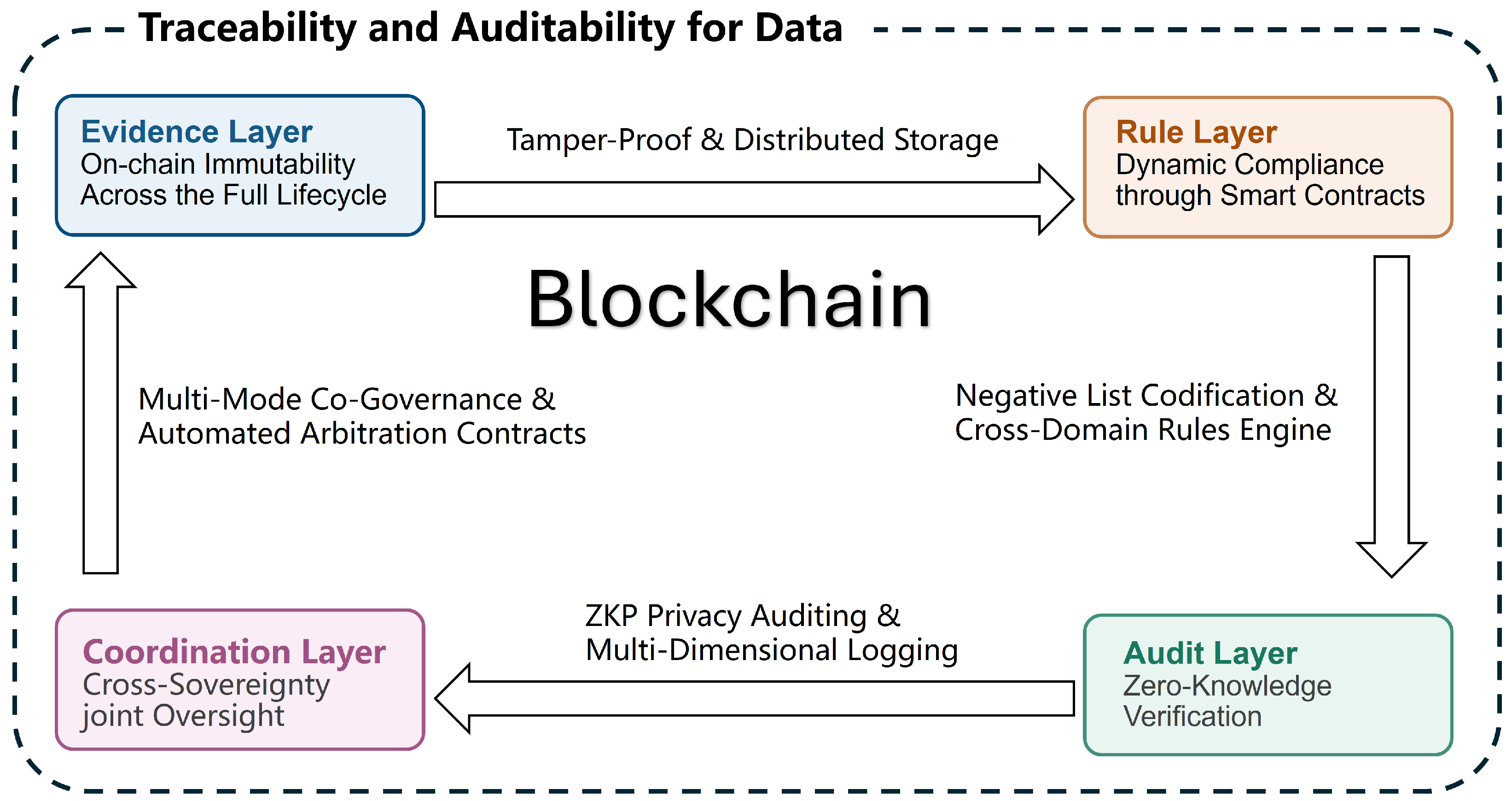

3.1.3. Strengthening Traceability and Auditing

- (1)

- Evidence layer: The entire life cycle of data generation, circulation, use, and extinction is recorded through the blockchain, and distributed storage is used to save the original data, achieving traceability in seconds.

- (2)

- Rule layer: Smart contracts embed data classification strategies and negative lists into the code and use natural language processing to parse legal provisions to generate executable compliance templates.

- (3)

- Audit layer: A zero-knowledge proof is used to verify whether data operations comply with policies, and SRv6 traffic labels and on-chain evidence are combined to form a visual audit map and realize multi-dimensional log analysis.

- (4)

- Collaboration layer: Regulatory agencies are introduced as authoritative nodes, multi-party co-governance and automated execution of arbitration contracts, and dispute resolution using verifiable credentials.

3.2. Cross-Border Data Governance

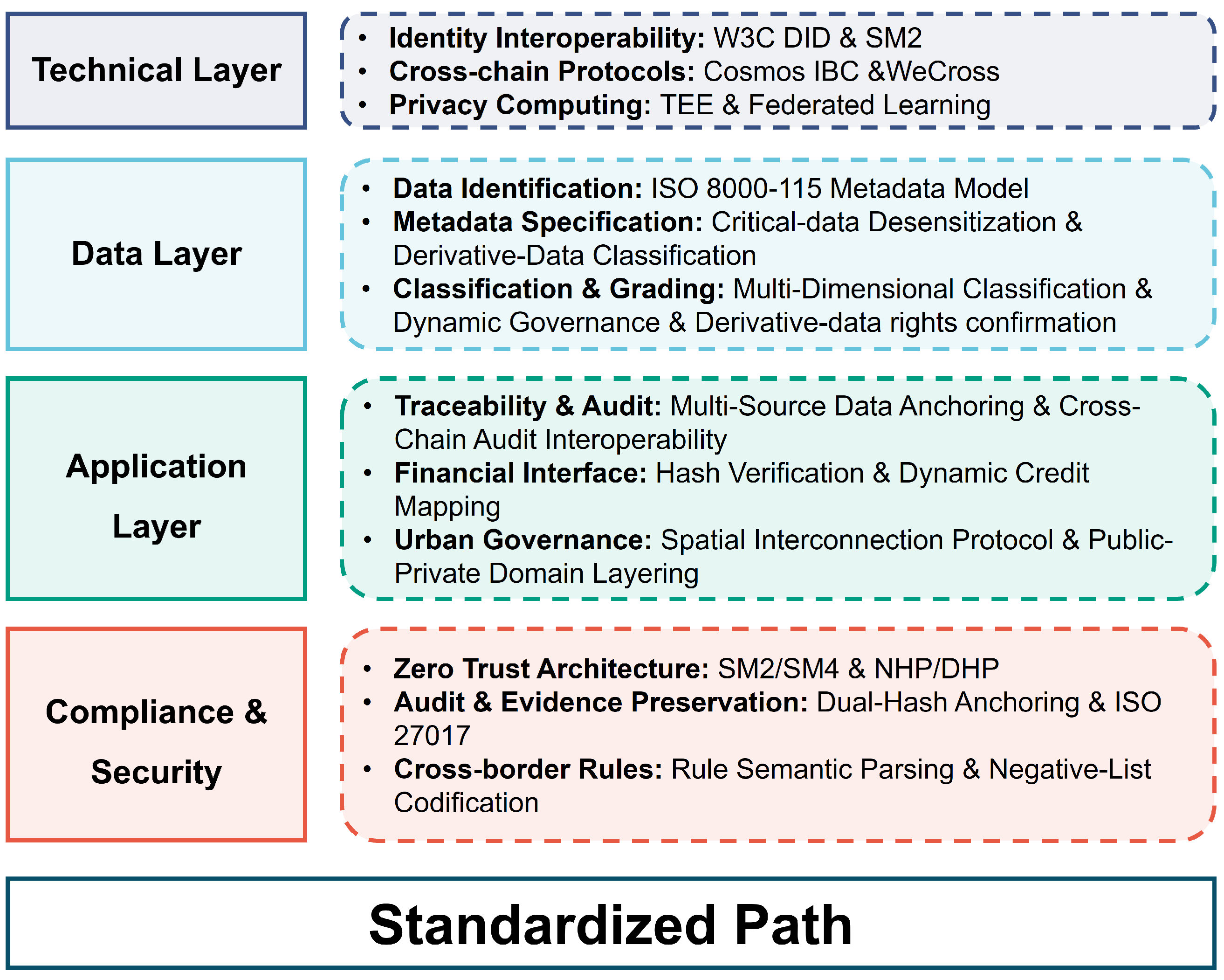

3.3. Standardized Path

- (1)

- Technical layer standards: These focus on making different computer systems work together, especially concerning digital identity, connecting different blockchains, and protecting private information. For digital identity, the standards combine W3C decentralized identifiers (DIDs) [78], a secure way to represent users online, with SM2, a cryptographic algorithm. Developments in connecting blockchains have been made by joining the Cosmos Inter-Blockchain Communication (IBC) protocol with enterprise platforms that offer blockchain services. Privacy-focused systems now also provide ways for different computers to work together securely using trusted execution environments (TEEs), which protect data even when it is in use, and federated learning, where multiple systems can analyze data together without sharing sensitive information.

- (2)

- Data layer standards: These standards emphasize data identification, metadata specifications, and hierarchical classification schemes to ensure semantic consistency throughout data circulation. Data identification can adopt the ISO 8000-115 [79] metadata model [80] to refine the rules for classification and grading implementation in industry as well as build a cross-domain understanding bridge based on JSON-LD and semantic interoperability.

- (3)

- Application layer standards: Vertical field standards should be formulated for supply chain traceability, financial services, and smart city governance scenarios. Traceability auditing incorporates hybrid standards combined with blockchain-based attestation mechanisms, establishing comprehensive “data, credit and product” mapping protocols in the financial field [81], and frameworks for cross-domain spatial interconnection interfaces are defined in urban governance to unify interaction rules across transportation and enterprise mobility scenarios [82].

- (4)

- Compliance and security standards: These reinforce systems where trust is never assumed, called zero-trust systems, and provide ways to check compliance and manage international rules. Zero-trust specifications control access to systems at all times. Protocols based on ISO 27017 verify compliance with the GDPR and national regulations. Coding rules for sending data across borders are automated to automatically check compliance.

4. Case Study and Validation

4.1. Case Introduction

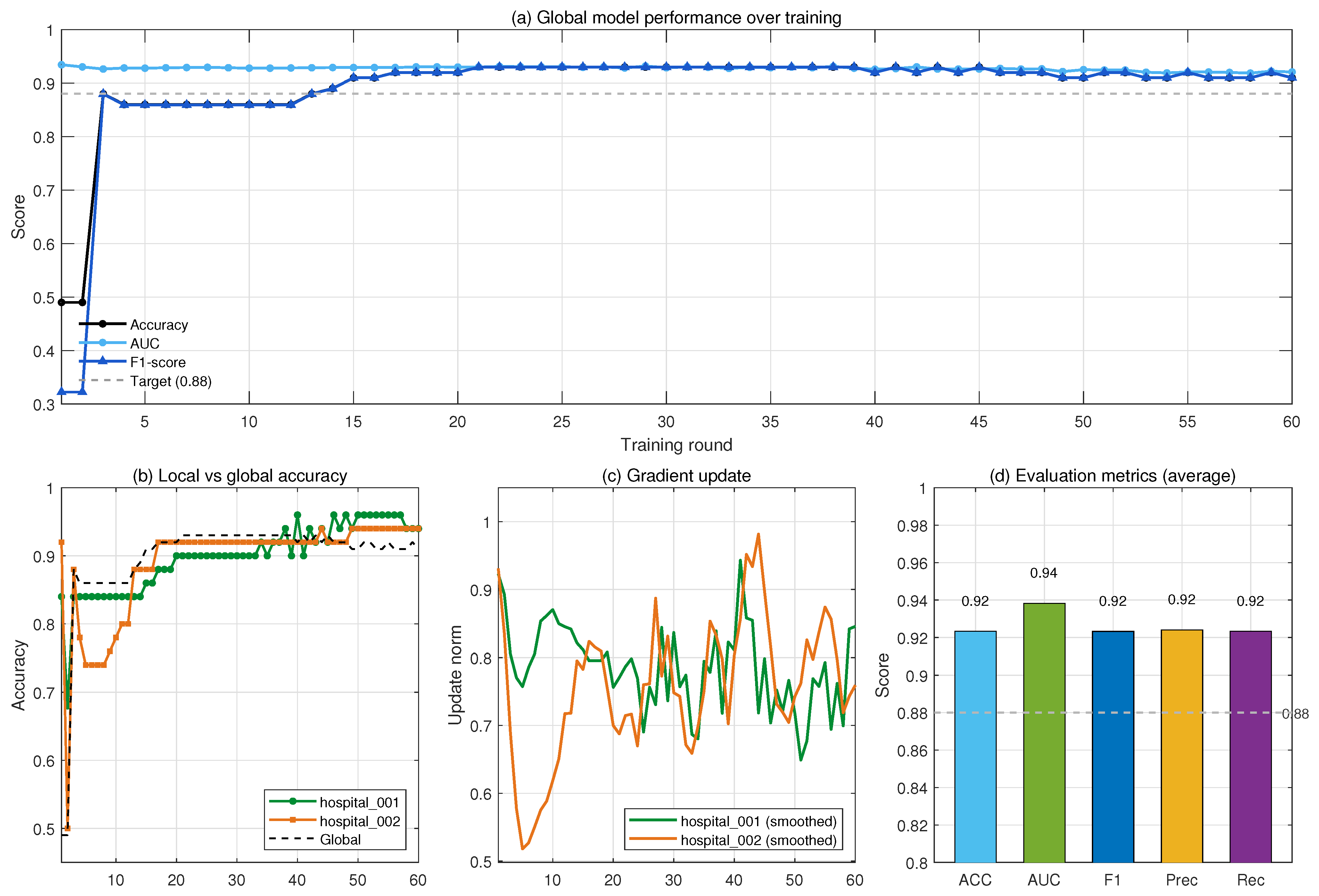

4.2. Verification Case and Evaluation Results

4.2.1. LPHS–XV Collaborative Trust Verification Scheme

- (1)

- On-Chain Light Attest

- (2)

- Off-Chain Deep Store

- (3)

- Cross-Layer Verifiable Bridge

4.2.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.2.3. Case Result Analysis

4.3. Case Summary and Outlook

5. Summary

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kar, S. Data for Better Lives: World Development Report 2021 by World Bank Group. J. Data Sci. Inf. Cit. Stud. 2023, 2, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Jun, S.P. Privacy-preserving data mining for open government data from heterogeneous sources. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, F.; Jussen, I.; Springer, V.; Gieß, A.; Schweihoff, J.C.; Gelhaar, J.; Guggenberger, T.; Otto, B. Industrial data ecosystems and data spaces. Electron. Mark. 2024, 34, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M.; Halevy, A.; Maier, D. From databases to dataspaces: A new abstraction for information management. ACM Sigmod Rec. 2005, 34, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, D. The Construction Principles and Development Paths of Trusted Data Spaces in China. J. Mod. Inf. 2025, 45, 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, B. A federated infrastructure for European data spaces. Commun. ACM 2022, 65, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacco, M.; Kocian, A.; Chessa, S.; Crivello, A.; Barsocchi, P. What are data spaces? Systematic survey and future outlook. Data Brief 2024, 57, 110969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieß, A.; Schoormann, T.; Möller, F.; Gür, I. Discovering data spaces: A classification of design options. Comput. Ind. 2025, 164, 104212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörandner, F.; Ramacher, S.; Roth, S. Selective end-to-end data-sharing in the cloud. J. Bank. Financ. Technol. 2020, 4, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A. Reconciling blockchain technology and data protection laws: Regulatory challenges, technical solutions, and practical pathways. J. Cybersecur. 2025, 11, tyaf002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Han, M. Data sharing and exchanging with incentive and optimization: A survey. Discov. Data 2024, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Sun, Y.; Ni, W.; Ding, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, W. Attacks against cross-chain systems and defense approaches: A contemporary survey. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2023, 10, 1647–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, T.; Moniz, N.; Faria, P.; Antunes, L. Towards a data privacy-predictive performance trade-off. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 223, 119785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanchangya, T.; Sarker, T.; Rahman, J.; Islam, M.S.; Islam, N.; Siddiqi, K.O. Mapping Blockchain Applications in FinTech: A Systematic Review of Eleven Key Domains. Information 2025, 16, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmanavičiūtė, L.; Masteika, S. Towards understanding the application areas of zero knowledge proof: A comprehensive analysis. In Proceedings of the 19th Prof. Vladas Gronskas International Scientific Conference, Kaunas, Lithuania, 29 November 2024; pp. 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Salles, M.A.V.; Dittrich, J.P.; Karakashian, S.K.; Girard, O.R.; Blunschi, L. iTrails: Pay-as-you-go Information Integration in Dataspaces. In Proceedings of the VLDB, Vienna, Austria, 23–28 September 2007; Volume 7, pp. 663–674. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, R. Integrating IoT and cloud computing for continuous process optimization in real-time systems. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2025, 6, 2540–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyskind, G.; Nathan, O.; Pentland, A.S. Decentralizing privacy: Using blockchain to protect personal data. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops, San Jose, CA, USA, 21–22 May 2015; pp. 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, A.; Wenzel, K.; Hänel, A.; Teicher, U.; Weiß, A.; Schäfer, U.; Ihlenfeldt, S.; Eisenmann, H.; Ernst, H. Towards a seamless data cycle for space components: Considerations from the growing European future digital ecosystem Gaia-X. CEAS Space J. 2024, 16, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Qin, B.; Zhai, M.; Susillo, W. Secure and fair data trading based on blockchain with enhanced access control. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 7277–7292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Xu, M.; Yang, X.; Li, P.; Yang, C.; Liu, Q.; Xiong, X.; Chen, P.; Wang, W. Trans-border Trusted Data Spaces: A General Framework Supporting Trustworthy International Data Circulation. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 30481–30496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessi, N.; Pes, B. Towards scientific dataspaces. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Joint Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology, Milan, Italy, 15–18 September 2009; Volume 3, pp. 575–578. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Jain, S. A survey on dataspace. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Network Security and Applications, Chennai, India, 15–17 July 2011; pp. 608–621. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, B.; Jürjens, J.; Schon, J.; Auer, S.; Menz, N.; Wenzel, S.; Cirullies, J. Industrial Data Space: Digital Souvereignity over Data; Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft: München, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Wang, G.; White, B.; Cottrell, R.L. A blockchain-based decentralized data storage and access framework for pinger. In Proceedings of the 2018 17th IEEE International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications/12th IEEE International Conference on Big Data Science and Engineering (TrustCom/BigDataSE), New York, NY, USA, 1–3 August 2018; pp. 1303–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Jarke, M.; Otto, B.; Ram, S. Data sovereignty and data space ecosystems. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2019, 61, 549–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. SSRN Electron. J. 2008, 3440802, 10-2139. [Google Scholar]

- Priyanshu, S.; Kumar, S.; Garg, S. Blockchain-Based Data Security. In Digital Forensics and Cyber Crime Investigation: Recent Advances and Future Directions; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, M. Overview of colored coins. White Pap. 2012, 41, 94. [Google Scholar]

- Counterparty Community. Counterparty (Platform). 2025. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Counterparty_(platform) (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Buterin, V. A next-generation smart contract and decentralized application platform. White Pap. 2014, 3, 2-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cuffe, P. The role of the erc-20 token standard in a financial revolution: The case of initial coin offerings. In Proceedings of the IEC-IEEE-KATS Academic Challenge, Busan, Korea, 22–23 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Benet, J. Ipfs-content addressed, versioned, p2p file system. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1407.3561. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, D.P. Filecoin. In Getting Started with Ethereum: A Step-by-Step Guide to Becoming a Blockchain Developer; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, Á.; Pozo, A.; Cantera, J.M.; De la Vega, F.; Hierro, J.J. Industrial data space architecture implementation using FIWARE. Sensors 2018, 18, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaler, J. Proofs, arguments, and zero-knowledge. Found. Trends® Priv. Secur. 2022, 4, 117–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belchior, R.; Vasconcelos, A.; Guerreiro, S.; Correia, M. A survey on blockchain interoperability: Past, present, and future trends. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldwasser, S.; Micali, S.; Rackoff, C. The knowledge complexity of interactive proof-systems. In Providing Sound Foundations for Cryptography: On the Work of Shafi Goldwasser and Silvio Micali; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Schnorr, C.P. Efficient signature generation by smart cards. J. Cryptol. 1991, 4, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiat, A.; Shamir, A. How to prove yourself: Practical solutions to identification and signature problems. In Proceedings of the Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques, Linköping, Sweden, 20–22 May 1986; pp. 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Groth, J. On the size of pairing-based non-interactive arguments. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Vienna, Austria, 8–12 May 2016; pp. 305–326. [Google Scholar]

- Gabizon, A.; Williamson, Z.J.; Ciobotaru, O. PLONK: Permutations over Lagrange-Bases for Oecumenical Noninteractive Arguments of Knowledge. Report 2019/953. Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2019; Preprint. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/953 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Boneh, D.; Drake, J.; Fisch, B.; Gabizon, A. Halo infinite: Proof-carrying data from additive polynomial commitments. In Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference, Virtual, 16–20 August 2021; pp. 649–680. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson, E.; Bentov, I.; Horesh, Y.; Riabzev, M. Scalable, Transparent, and Post-Quantum Secure Computational Integrity. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2018; 46, preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson, E.; Bentov, I.; Horesh, Y.; Riabzev, M. Fast reed–solomon interactive oracle proofs of proximity. In Proceedings of the 45th International Colloquium on Automata, Languages, and Programming (ICALP 2018), Prague, Czech Republic, 9–13 July 2018; pp. 14:1–14:17. [Google Scholar]

- Bünz, B.; Bootle, J.; Boneh, D.; Poelstra, A.; Wuille, P.; Maxwell, G. Bulletproofs: Short proofs for confidential transactions and more. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–24 May 2018; pp. 315–334. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H.; Han, K.; Ju, C.; Kim, M.; Seo, J.H. Bulletproofs+: Shorter proofs for a privacy-enhanced distributed ledger. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 42081–42096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Hu, Y.; He, J.; Fan, H.; An, Z. Health-zkIDM: A healthcare identity system based on fabric blockchain and zero-knowledge proof. Sensors 2022, 22, 7716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, S.; Hassanizadeh, P. From Interaction to Independence: zkSNARKs for Transparent and Non-Interactive Remote Attestation. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2024, 2024, 1068. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, C.; Chowdhury, A.R.; Boneh, D.; Chaudhuri, K. Fairproof: Confidential and certifiable fairness for neural networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.12572. [Google Scholar]

- Adida, B. Helios: Web-based Open-Audit Voting. In Proceedings of the USENIX Security Symposium, San Jose, CA, USA, 28 July–1 August 2008; Volume 17, pp. 335–348. [Google Scholar]

- Setty, S. Spartan: Efficient and general-purpose zkSNARKs without trusted setup. In Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 17–21 August 2020; pp. 704–737. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.J.; Waiwitlikhit, S.; Stoica, I.; Kang, D. Zkml: An optimizing system for ml inference in zero-knowledge proofs. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth European Conference on Computer Systems, Athens, Greece, 22–25 April 2024; pp. 560–574. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, E.T.M.; Pérez, M.Q.; Sánchez, P.M.S.; Bernal, S.L.; Bovet, G.; Pérez, M.G.; Pérez, G.M.; Celdrán, A.H. Decentralized federated learning: Fundamentals, state of the art, frameworks, trends, and challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 2983–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. (TIST) 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Hard, A.; Rao, K.; Mathews, R.; Ramaswamy, S.; Beaufays, F.; Augenstein, S.; Eichner, H.; Kiddon, C.; Ramage, D. Federated learning for mobile keyboard prediction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1811.03604. [Google Scholar]

- Minto, L.; Haller, M.; Livshits, B.; Haddadi, H. Stronger privacy for federated collaborative filtering with implicit feedback. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 342–350. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, S.; Henecka, W.; Ivey-Law, H.; Nock, R.; Patrini, G.; Smith, G.; Thorne, B. Private federated learning on vertically partitioned data via entity resolution and additively homomorphic encryption. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.10677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, R.; Hardy, S.; Henecka, W.; Ivey-Law, H.; Patrini, G.; Smith, G.; Thorne, B. Entity resolution and federated learning get a federated resolution. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.04035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Cai, S.; Xiao, X.; Chen, G.; Ooi, B.C. Privacy preserving vertical federated learning for tree-based models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.06170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Fan, T.; Jin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Papadopoulos, D.; Yang, Q. Secureboost: A lossless federated learning framework. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2021, 36, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, L.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, F. Multimodal federated learning: A survey. Sensors 2023, 23, 6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhuang, F.; Zhang, X.; Tong, Y.; Dong, J. A comprehensive survey of federated transfer learning: Challenges, methods and applications. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 18, 186356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Miao, T.; Mirian, N.; Chen, X.; Xie, H.; Feng, Z.; Guo, X.; Li, X.; Zhou, S.K.; Duncan, J.S.; et al. Federated transfer learning for low-dose PET denoising: A pilot study with simulated heterogeneous data. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 2022, 7, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Chen, D.; Qian, B.; Yao, L.; Li, Y. Federated fine-tuning of large language models under heterogeneous tasks and client resources. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 14457–14483. [Google Scholar]

- Kosba, A.; Miller, A.; Shi, E.; Wen, Z.; Papamanthou, C. Hawk: The blockchain model of cryptography and privacy-preserving smart contracts. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Jose, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 839–858. [Google Scholar]

- Bünz, B.; Agrawal, S.; Zamani, M.; Boneh, D. Zether: Towards privacy in a smart contract world. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 10–14 February 2020; pp. 423–443. [Google Scholar]

- Mühle, A.; Grüner, A.; Gayvoronskaya, T.; Meinel, C. A survey on essential components of a self-sovereign identity. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2018, 30, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, B.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Shi, W. A scalable cross-chain access control and identity authentication scheme. Sensors 2023, 23, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, A.G.; Eram, A.; Talburt, J.R. ISO 8000-61 Data Quality Management Standard, TDQM Compliance, IQ Principles. In Proceedings of the MIT International Conference on Information Quality, Little Rock, AR, USA, 6–7 October 2017; pp. 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaruddin, N.A.; Mohamed, I.; Jarno, A.D.; Daud, M. Cloud Security Pre-assessment Model For Cloud Service Provider Based On ISO/IEC 27017: 2015 Additional Control. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Global Business and Social Science 2020 (3rd ICGBSS 2020), Online, 3–4 October 2020; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Panek, W. People’s Republic of China and the adequacy–Why Chinese data protection law is not adequate within the meaning of the GDPR. Masaryk. Univ. J. Law Technol. 2024, 18, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokhbeh Zaeem, R.; Chang, K.C.; Huang, T.C.; Liau, D.; Song, W.; Tyagi, A.; Khalil, M.; Lamison, M.; Pandey, S.; Barber, K.S. Blockchain-based self-sovereign identity: Survey, requirements, use-cases, and comparative study. In Proceedings of the IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology, Melbourne, Australia, 14–17 December 2021; pp. 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Firdausy, D.; Silva, P.D.A.; van Sinderen, M.J.; Iacob, M.E. Semantic discovery and selection of data connectors in international data spaces. In Proceedings of the Interoperability for Enterprise Systems and Applications, I-ESA 2022, Valencia, Spain, 23–25 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- W3C DID v1.0; Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) v1.0; World Wide Web Consortium (W3C): Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022.

- ISO/IEC 27017:2015; Information Technology—Security Techniques—Code of Practice for Information Security Controls Based on ISO/IEC 27002 for Cloud Services. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Reed, D.; Sporny, M.; Longley, D.; Allen, C.; Grant, R.; Sabadello, M.; Holt, J. Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs) v1.0.; Draft Community Group Report; W3C: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 8000-115:2024; Data quality—Part 115: Master Data: Exchange of Quality Identifiers: Syntactic, Semantic and Resolution Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Gualo, F.; Caballero, I.; Rodriguez, M. Towards a software quality certification of master data-based applications. Softw. Qual. J. 2020, 28, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, T.; Ghita, B. Perspectives on Auditing and Regulatory Compliance in Blockchain Transactions. In Trust Models for Next-Generation Blockchain Ecosystems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 37–65. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; He, J.; Fang, X.; Luo, L.; Tian, C. Overall framework of IoT platform in urban agglomeration-cross-city, cross-domain, cross-level, and one-network unified management architecture. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Internet of Things and Machine Learning (IoTML 2023), Singapore, 15–17 September 2023; Volume 12937, pp. 239–247. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.P.; Morrison, P.; Dao, L. COVID-19 image data collection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.11597. [Google Scholar]

- Mironov, I. Rényi differential privacy. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 30th Computer Security Foundations Symposium (CSF), Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 21–25 August 2017; pp. 263–275. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ren, G.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S.; He, L.; Jia, Y. Building an IPv6 address generation and traceback system with NIDTGA in Address Driven Network. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2015, 58, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Shetty, S.; Tosh, D.; Kamhoua, C.; Kwiat, K.; Njilla, L. Provchain: A blockchain-based data provenance architecture in cloud environment with enhanced privacy and availability. In Proceedings of the 2017 17th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Grid Computing (CCGRID), Madrid, Spain, 14–17 May 2017; pp. 468–477. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Dou, H.; Chen, S.; Zhao, H. A Novel Block-chain based secure cross-domain interaction Approach for intelligent transportation systems. Phys. Commun. 2024, 63, 102223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Datta, A. Blockchain-enabled data governance for privacy-preserved sharing of confidential data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.D.; Ueyama, J. Blockchain-based data governance for privacy-preserving in multi-stakeholder settings. In Proceedings of the Anais Estendidos do XLII Simpósio Brasileiro de Redes de Computadores e Sistemas Distribuídos (SBRC 2024), Linköping, Sweden, 20–22 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Balachandar, S.K.; Prema, K.; Kamarajapandian, P.; Shantha Shalini, K.; Thanga Aruna, M.; Jaiganesh, S. Blockchain-enabled Data Governance Framework for Enhancing Security and Efficiency in Multi-Cloud Environments through Ethereum, IPFS, and Cloud Infrastructure Integration. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 2132–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widayanti, R.; Mutiara, A.B.; Tarigan, A. Data Governance in Blockchain-Based Systems for Internship Grade Conversion. Aptisi Trans. Technopreneurship (ATT) 2024, 6, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizal, M.; Mohemad, R.; Noor, N.M.M. A Systematic Literature Review on Blockchain for Implementation of Data Governance Framework. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2024, 102, 6448–6454. [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Reference | Year | Insights | Method | Contributions | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michael Franklin et al. [4] | 2005 | Replace the traditional DBMS’s “integrate first, then serve” paradigm with a “data space” paradigm for real heterogeneous data environments. | Conceptual modeling. | The concept of “Dataspaces (DSSP)” was systematically proposed for the first time, and several core research directions were clarified. | Lack of complete implementation and large-scale empirical evaluation. | |

| 1 | Salles, M.A.V. et al. [16] | 2007 | Marking user query behavior as low-cost mapping evidence to continuously improve integration quality. | Record trail metadata for each query and automatically discover or enhance schema mapping through path mining. | Implemented the first working pay-as-you-go prototype system iMeMex. | Affected by the cold start. The quality of early queries is insufficient. |

| Dessi, N. et al. [22] | 2009 | Data spaces meet the traceability needs of scientific workflows and support reproducible experiments at a low cost. | Modeling “tracing traces” as a class of objects. | The Dataspaces concept was applied to reproducible scientific research applications for the first time. | It is mainly aimed at life science scenarios, and its universality remains to be verified. | |

| 2 | Singh, M. et al. [23] | 2011 | Data space research has taken shape along the four main lines of “system-model-query-index”. | Literature review and context elaboration. | Provides the first panoramic research map, summarizing the top 10 challenges for the future. | Lack of comparable evaluations of representative prototypes. |

| Zyskind, G. et al. [18] | 2015 | Blockchain as a decentralized access control and audit layer. | Encode grants as on-chain transactions with off-chain secure storage for privacy. | Establishes foundations for IDS and Gaia-X practice. | Incomplete standards and high cross-domain alignment cost. | |

| 3 | Otto, B. et al. [24] | 2016 | Industrial data needs to flow across enterprises and must have “provable sovereignty and visible control”. | Propose a layered architecture with “data space connector + usage contract”. | Systematize the concept of “digital sovereignty” in industrial scenarios. | Relying on unified IDS authentication results in high initial deployment costs and unresolved cross-border legal issues. |

| Ali, S. et al. [25] | 2018 | Scientific monitoring requires multi-party governed data spaces across borders. | Write monitoring records such as network latency into the private chain and use signature metadata to achieve traceability. | First real deployment of “blockchain and data space” in PingER infrastructure. | It is only suitable for low-frequency writing and high-value scenarios, and its versatility and scalability remain to be verified. | |

| 4 | Jarke, M. et al. [26] | 2019 | Data sovereignty, not mere privacy, underpins sustainable inter-organizational data spaces. | Alliance-driven ecosystem built on IDS with IDS or Gaia-X and other standardized components. | Establishes foundations for the International Data Space (IDS), Gaia-X, and other alliance practices. | Incomplete standards and high cross-domain alignment cost. |

| 5 | Feng, Z. et al. [20] | 2024 | Security and fairness for large-scale data exchange. | Blockchain and smart contracts with cryptography and auditable access control to protect privacy and fairness. | Delivers a transparent, tamper-resistant, and accountable trading paradigm. | Potential throughput or storage bottlenecks at decentralized scale. |

| Zhang, C. et al. [21] | 2025 | Trustworthy, interoperable data spaces for cross-border data flows. | Cross-border exchange protocols, trust anchors, and auditable logging with differentiated compliance controls. | A comprehensive architecture covering security, privacy, and compliance for global interoperability. | There may be challenges when dealing with cross-border compliance and policy differences. |

| Year | Phase | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2008–2011 | Proposal of decentralized ledger and cryptoeconomic paradigm. | Satoshi Nakamoto [27] introduced a peer-to-peer electronic cash system based on proof of work (PoW), thereby defining a cryptoeconomic paradigm of an “immutable ledger and decentralized consensus”. The genesis block created the following year empirically demonstrated the feasibility of trustless value transfer and open participation, providing a prototype of “timestamp as provenance” for subsequent data spaces. |

| 2012–2015 | Universal Programmable Ledger and Smart Contract Platform. | Colored Coins (2012) [29], Counterparty (2014) [30], and others attempted to attach assets or data to the Bitcoin script layer. With the launch of Ethereum (2015) [31], Turing-complete smart contracts upgraded the “chain” to a “global state machine”, and the chain began to carry data logic other than tokens, laying the script foundation for subsequent interaction between in-chain data and off-chain space. |

| 2016–2018 | On-chain data governance ecosystem. | The ICO boom and establishment of the ERC20 and ERC721 [32] standards led to an explosion of on-chain native data assets (tokens and NFTs). IPFS [33] and Filecoin [34] introduced the concept of a distributed storage layer, making the “chain-data-space” ternary structure explicit for the first time. The chain is responsible for confirming ownership, and IPFS is responsible for addressing large blocks of content, forming the prototype of “on-chain index and off-chain space”. |

| 2019–2021 | Cross-chain interoperability and crystallization of on-chain governance. | The EU launched the International Data Space (IDS) and Gaia-X initiatives, proposing the concept of a “sovereign data space” [35]. Enterprise blockchains such as Hyperledger and Quorum have begun to connect to IDS connectors to realize “the chain as a data space node”, using hashes and signatures to write fine-grained off-chain data access policies onto the chain, thus achieving trusted circulation under compliant conditions. |

| 2022–2023 | Metaverse, digital twins, and AIGC are giving rise to large-scale 3D and spatiotemporal data. | The blockchain, as the “data price signal” layer, introduces compute-to-data, ZKP and verifiable computation (VC) [36], enabling data to be trained or rendered as “usable but invisible” in three-dimensional space. New block types such as “data space ID” and “proof of spatial location (PL)” are beginning to appear on the chain, realizing the three-way binding of data content, spatiotemporal coordinates, and ownership. |

| 2024–Present | Institutionalization of trustworthy data infrastructure and cross-domain data governance. | With the maturity of multi-chain interoperability, cross-domain identity (DID and VC), and spatial rendering protocols (OpenXR-on-chain), an integrated network of “blockchain-data space-spatial computing” is formed. The blockchain is upgraded to a “trusted data bus”, where any physical or virtual space can become a data domain with autonomous sovereignty. On-chain smart contracts automatically complete data ownership confirmation, pricing, authorization, settlement, and auditing. Data is “usable but invisible, controllable and measurable” across domains, ushering in a large-scale trusted data space era of “chain-driven data, spatial computing, and contract governance” [37]. |

| Protocol | Interactivity | Core Primitives | Typical Applications | Main Advantages | Representative Schemes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -protocol | Interactive | Number theory | Authentication; proof-of-knowledge primitive | Simple and easy to analyze, mature implementations | Schnorr [39]; Fiat–Shamir [40] |

| zk-SNARK | Non-interactive | Elliptic curves and pairings; KZG | Private payments; zkRollups; zkVMs | Short proofs, cheap on-chain verification, mature ecosystem | Groth16 [41]; PLONK [42]; Halo2 [43] |

| zk-STARK | Non-interactive | Hash/IOP and FRI/coding theory | Large-scale verifiable computation; roll ups; recursive composition | Transparent, scalable, long-term security | STARK [44]; FRI [45]; |

| Bulletproofs | Non-interactive | DLP and inner product; Pedersen commitments | Range proofs; confidential transactions; set membership | No set-up, short proofs, aggregatable | Bulletproofs [46]; Bulletproofs+ [47] |

| Framework | Source Code Link |

|---|---|

| TFF | https://github.com/tensorflow/federated (Access date: 24 October 2025) |

| PySyft | https://github.com/OpenMined/PySyft (Access date: 24 October 2025) |

| FATE | https://github.com/FederatedAI/FATE (Access date: 24 October 2025) |

| FederatedScope-LLM | https://github.com/dbookbeatbuzz/FederatedScope-llm (Access date: 29 November 2025) |

| Work | Blockchain or Network Type | On-Chain vs. off-Chain Data Partition | Key Techniques | Governance Logic Implementation | Application Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | Blockchain as trust infrastructure for cross-organizational, cross-regional and cross-border trustworthy data spaces. | LPHS–XV: light proofs and compliance metadata stored on-chain; sensitive data stored off-chain and linked via a cross-layer verifiable bridge | Blockchain and ZKP with FL to build a collaborative trust mechanism, achieving data availability without visibility and compliance auditability | Technology–governance–standardization (TGS) framework jointly modeling technical mechanisms, governance rules, and standards for cross-border data-space governance | Explicitly targets cross-organizational, cross-regional, and cross-border trustworthy data spaces |

| Zhang and Datta 2024 [88] | Ethereum-like smart-contract blockchain and IPFS decentralized storage | Authorities, access policies, authorizations, and logs on-chain; confidential data encrypted by multi-authority CP-ABE and AES and stored in IPFS off-chain | Multi-authority CP-ABE (policy hiding, identity privacy) and AES with formal security analysis against illegal authorization | Smart contracts implement authority management, key issuance, data upload, and access control, embedding accountability into the ledger | Multi-organization cloud data sharing; not explicitly designed for cross-border governance |

| Garcia et al. 2024 [89] | Decentralized blockchain with prototypes on CosmWasm, Hyperledger Besu, and Ethereum | Data provenance, access events and consent on-chain; business data (e.g., e-prescriptions) protected by PRE stored off-chain | Proxy re-encryption (PRE) + BBS signatures for selective disclosure, consent management, and verifiable provenance | Smart contracts orchestrate data owner authorization, revocation and tracking workflows, executing privacy and consent management on-chain | Focuses on multi-stakeholder health and IoT scenarios, mostly within single jurisdictions |

| Balachandar et al. 2024 [90] | Private Ethereum (PoA consensus) + IPFS + multi-cloud infrastructure (OpenStack or OpenShift) | Data transactions, access records and governance metadata on-chain; large-scale business data and files stored off-chain across clouds and IPFS | Blockchain immutability + access control + encrypted communication; no advanced PETs such as ZKP or ABE | Smart contracts bind data access policies to cloud operations (store, replicate, and migrate), realizing policy-as-code governance and auditing | Supports multi-cloud and cross-region deployment; cross-border legal and compliance issues not explicitly modeled |

| Widayanti et al. 2024 [91] | Private or consortium blockchain in a university–industry collaboration setting | Internship grades, conversion rules, and approval workflows on-chain; detailed records remain in existing university and company systems | Immutable ledger + identity management + basic cryptography to ensure grade integrity, fairness, and accountability | On-chain modeling of internship grade conversion and approval workflows, binding roles (university, company, and regulator) to permissions | Cross-organization governance between universities and companies; cross-border data spaces not considered |

| Feizal et al. 2024 [92] | Systematic review of public, consortium, and private blockchains for data governance | Synthesizes patterns with identity, policies, and audit logs on-chain and business data off-chain; no concrete architecture proposed | Surveys ABE, smart contracts, encrypted storage, and other techniques, discussing scenarios, strengths, and limitations | Proposes a “when, why, who, and how” analytical framework and clarifies roles of data owners, users, and monitors in blockchain-based data governance | Covers multiple domains and multi-party settings; cross-border governance discussed only at a high level |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, Z.-Y.; Liu, G.-Y.; Ren, Y.; Yang, M.; Jiang, R.-W.; Luo, Y.; Ma, Y.-S. Trustworthy Data Space Collaborative Trust Mechanism Driven by Blockchain: Technology Integration, Cross-Border Governance, and Standardization Path. Information 2025, 16, 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121066

Liang Z-Y, Liu G-Y, Ren Y, Yang M, Jiang R-W, Luo Y, Ma Y-S. Trustworthy Data Space Collaborative Trust Mechanism Driven by Blockchain: Technology Integration, Cross-Border Governance, and Standardization Path. Information. 2025; 16(12):1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121066

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Zhi-Yong, Gao-Yuan Liu, Yi Ren, Ming Yang, Rong-Wang Jiang, Yang Luo, and Yu-Shi Ma. 2025. "Trustworthy Data Space Collaborative Trust Mechanism Driven by Blockchain: Technology Integration, Cross-Border Governance, and Standardization Path" Information 16, no. 12: 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121066

APA StyleLiang, Z.-Y., Liu, G.-Y., Ren, Y., Yang, M., Jiang, R.-W., Luo, Y., & Ma, Y.-S. (2025). Trustworthy Data Space Collaborative Trust Mechanism Driven by Blockchain: Technology Integration, Cross-Border Governance, and Standardization Path. Information, 16(12), 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121066