Fully-Cascaded Spatial-Aware Convolutional Network for Motion Deblurring

Abstract

1. Introduction

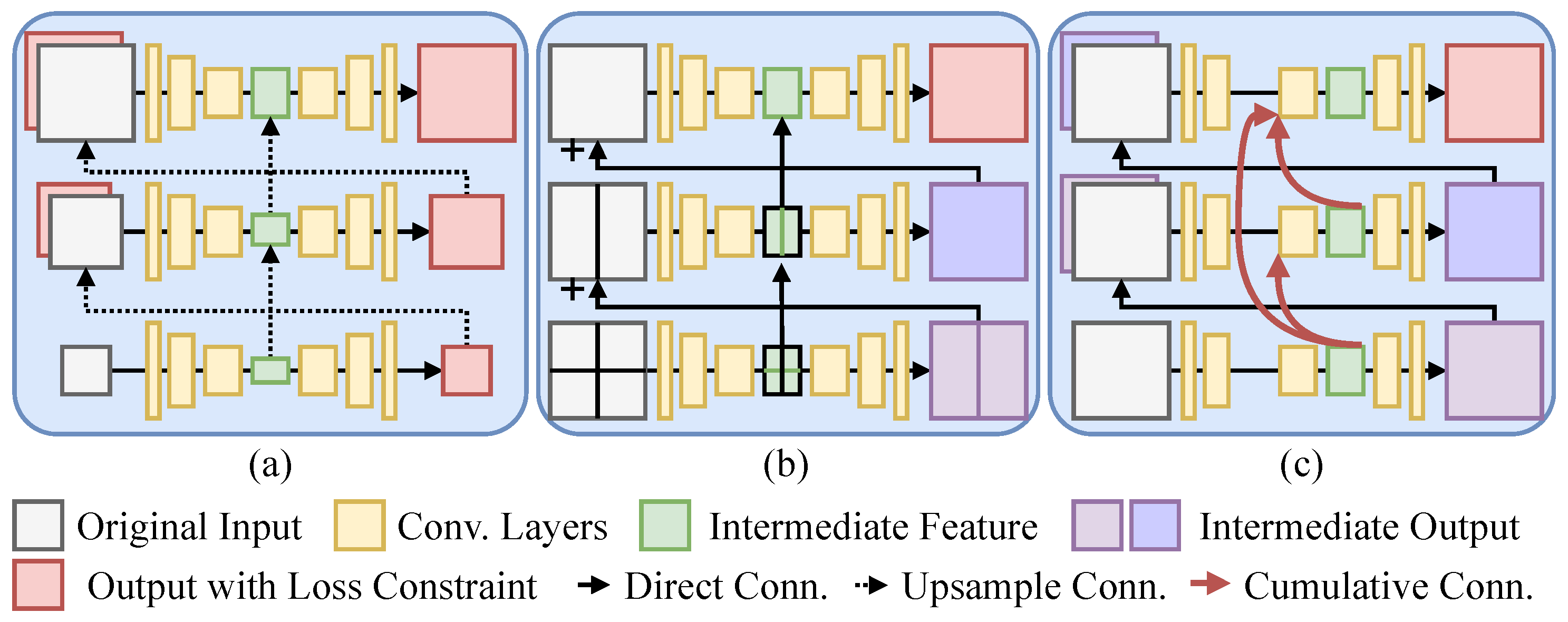

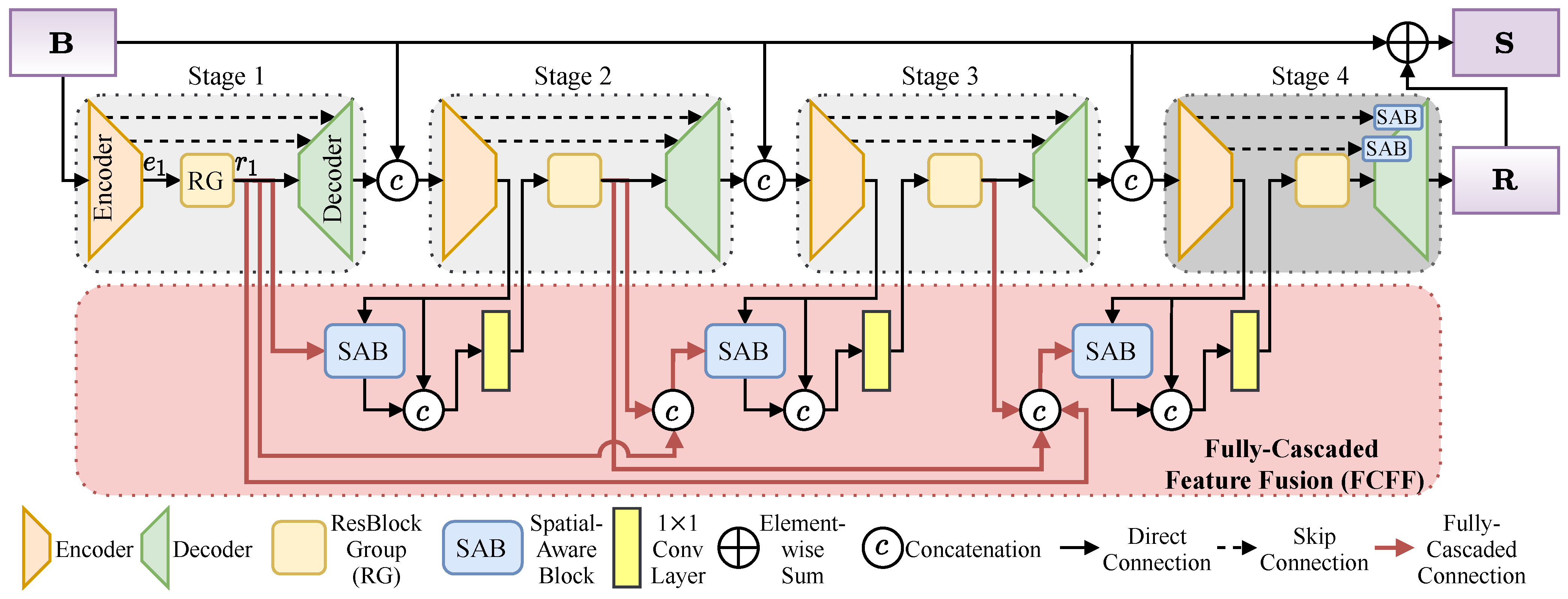

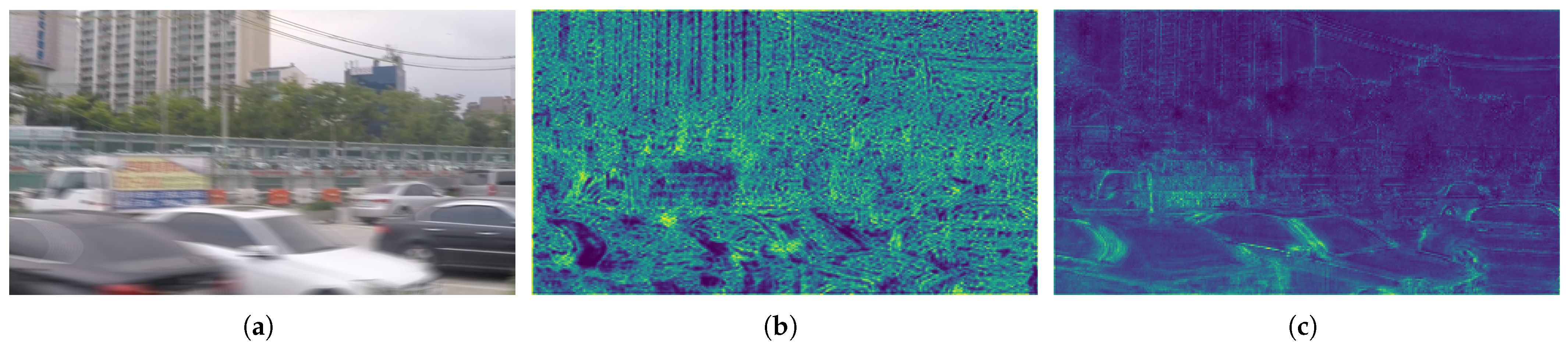

- We design a simple yet effective deblurring network with invariant-scale inputs. This network consists of multi-stage sub-networks, which process input images without downscaling them or splitting them into patches, as shown in Figure 1c. Moreover, we fully cascade all sub-networks (rather than only two adjacent ones) to enable each higher-level sub-network to progressively reuse features from all lower-level sub-networks.

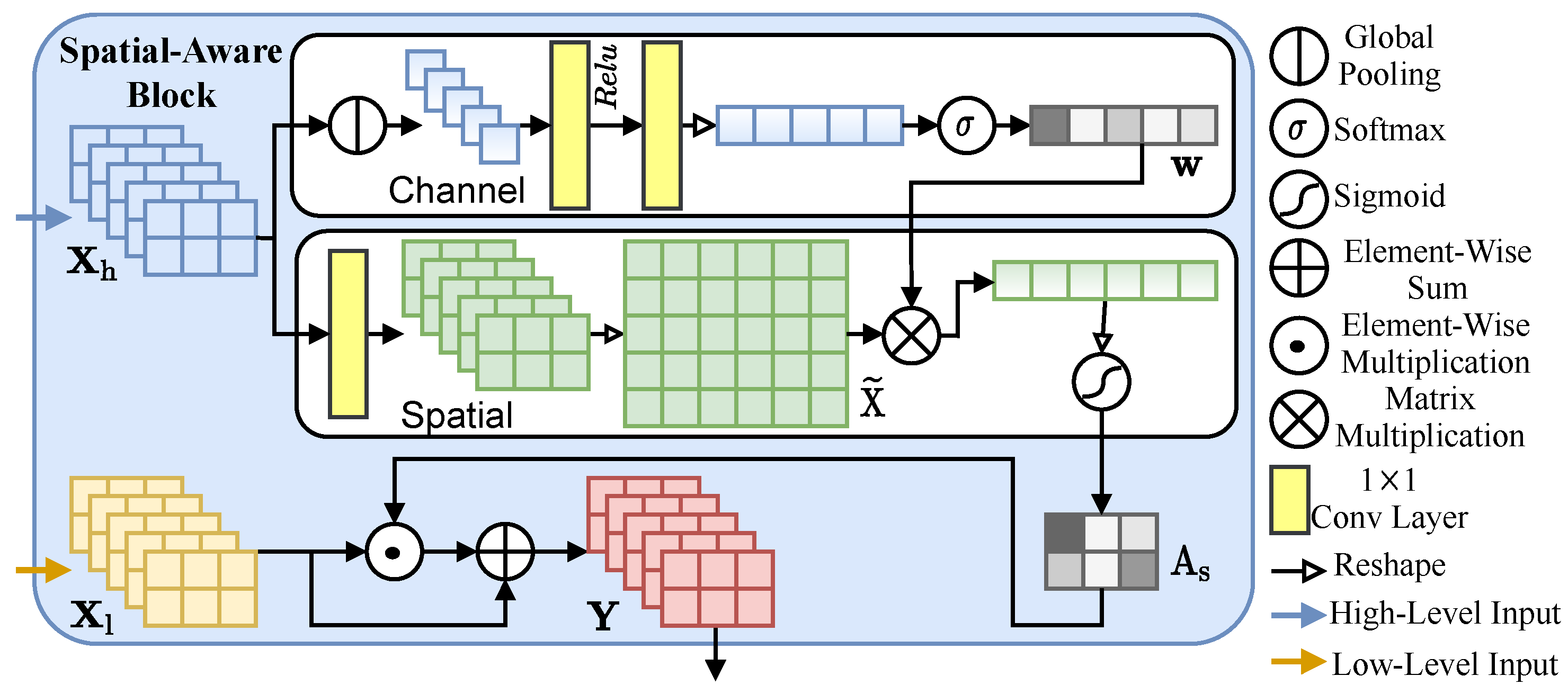

- We devise a lightweight spatial-aware block (SAB) that incorporates a novel channel-weighted spatial attention (CWSA) mechanism, which adopts a channel-weighted summation instead of the conventional channel pooling. SAB enhances the extraction and representation of spatial features. When integrated into both the fully-cascaded feature fusion (FCFF) and skip connections, SAB facilitates more effective feature fusion and spatial detail compensation, thereby further improving deblurring performance.

- We conduct extensive experiments on four representative datasets to evaluate the performance of the proposed FSCNet. Experimental results demonstrate that our method outperforms the state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods while maintaining a favorable performance–complexity trade-off.

2. Related Work

2.1. End-to-End Deblurring Driven by Convolutional Networks

2.2. Attention-Enhanced Deblurring in Convolutional Networks

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview

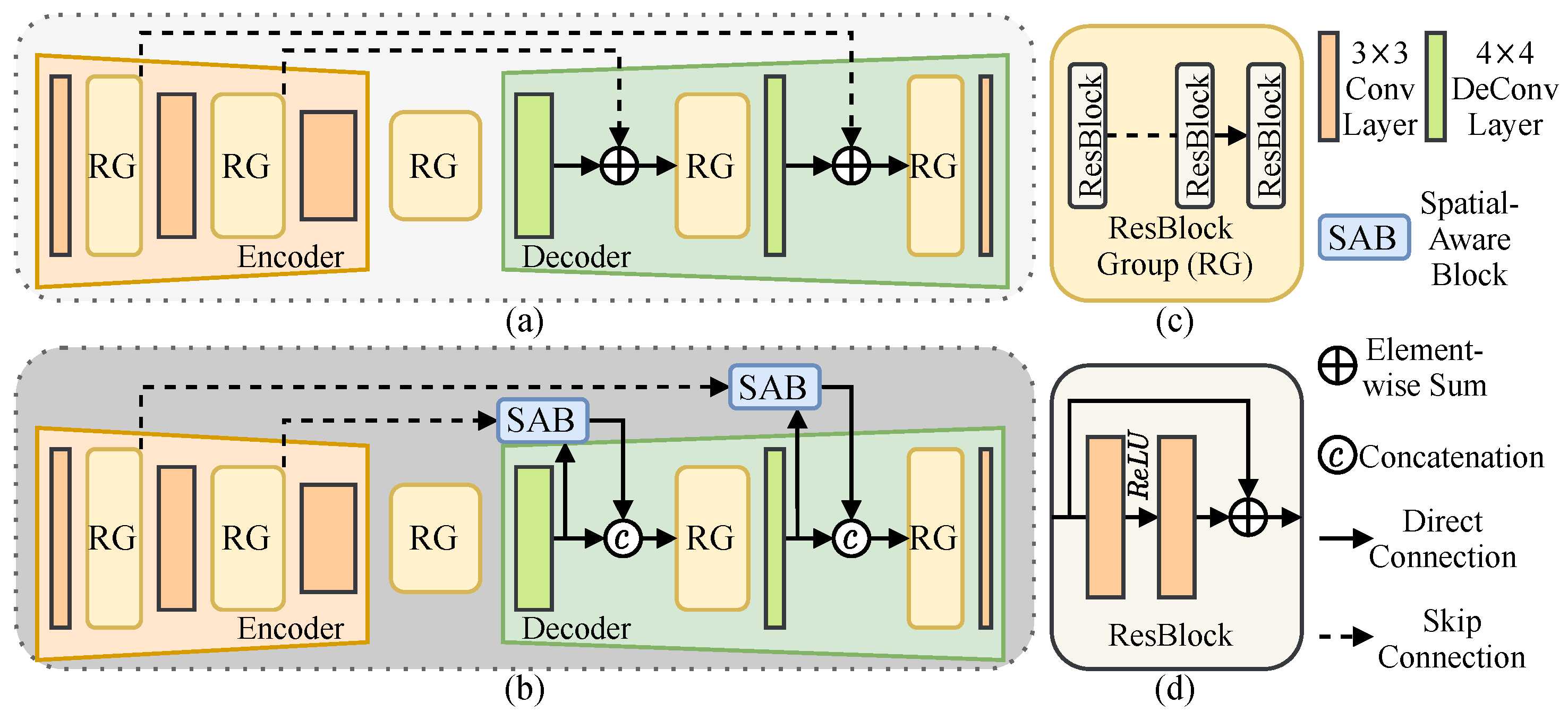

3.2. Multi-Stage Sub-Networks

3.3. Fully-Cascaded Feature Fusion

3.4. Spatial-Aware Block

3.5. Loss Function

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Settings

4.2. Ablation Study

4.2.1. Impact of the Number of Stacked ResBlocks in RG

4.2.2. Effectiveness of the Base Architecture, FCFF, and SAB

- M1: Base architecture only, without FCFF and all SAB modules; represents the efficient invariant-scale input foundation.

- M2: M1 combined with FCFF (without SABs); used to assess the contribution of FCFF on the base framework.

- M3: M2 with additional SABs applied to the last stage; used to evaluate the individual effect of the last-stage SABs.

- M4: M1 integrated with FCFF (with SABs); used to verify SAB’s role in feature fusion.

- FSCNet: M1 integrated with FCFF (with SABs) and last-stage SABs; represents the full configuration.

4.2.3. Validation of CWSA in SAB

4.3. Performance Comparisons

4.3.1. Quantitative Evaluations

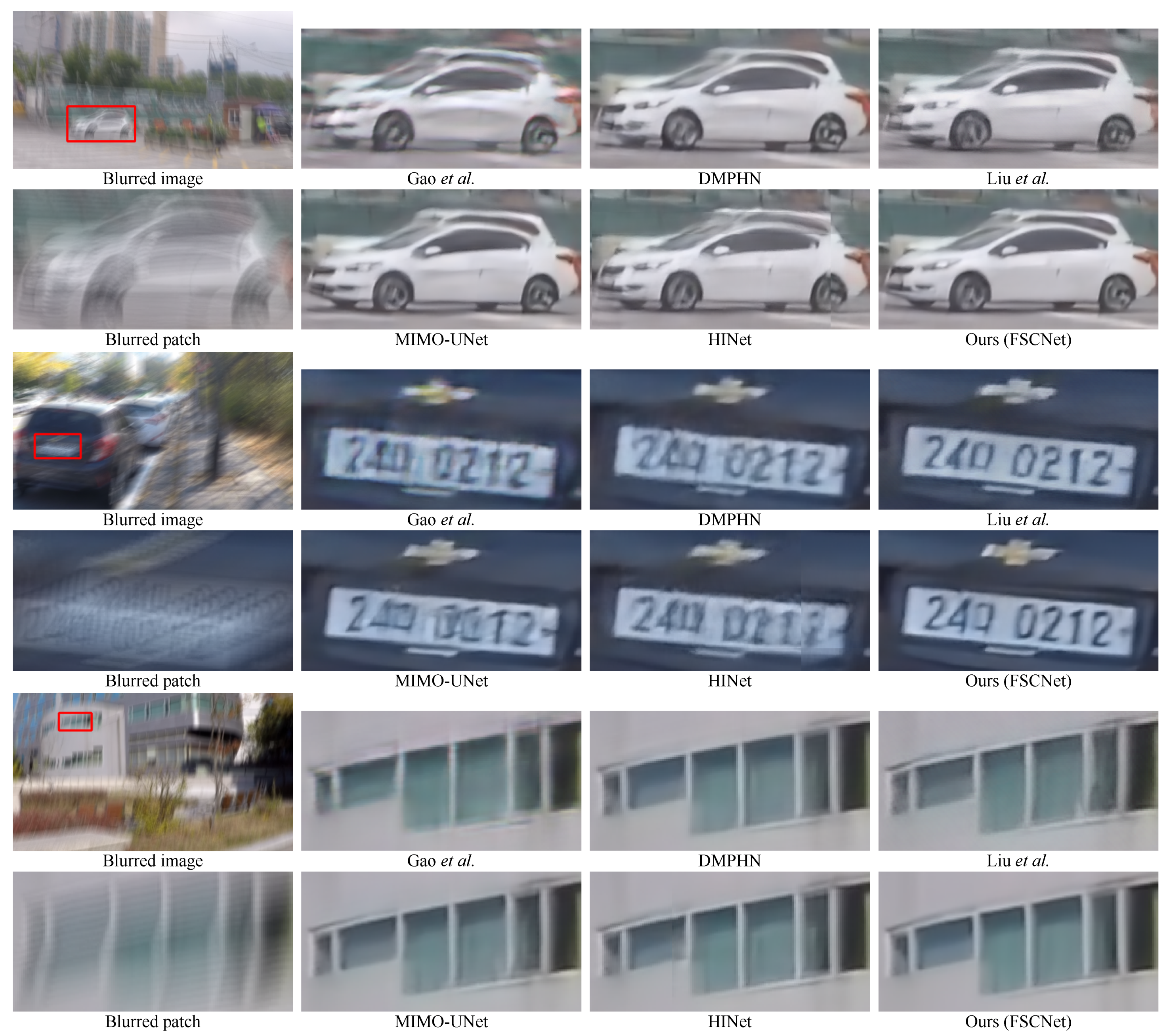

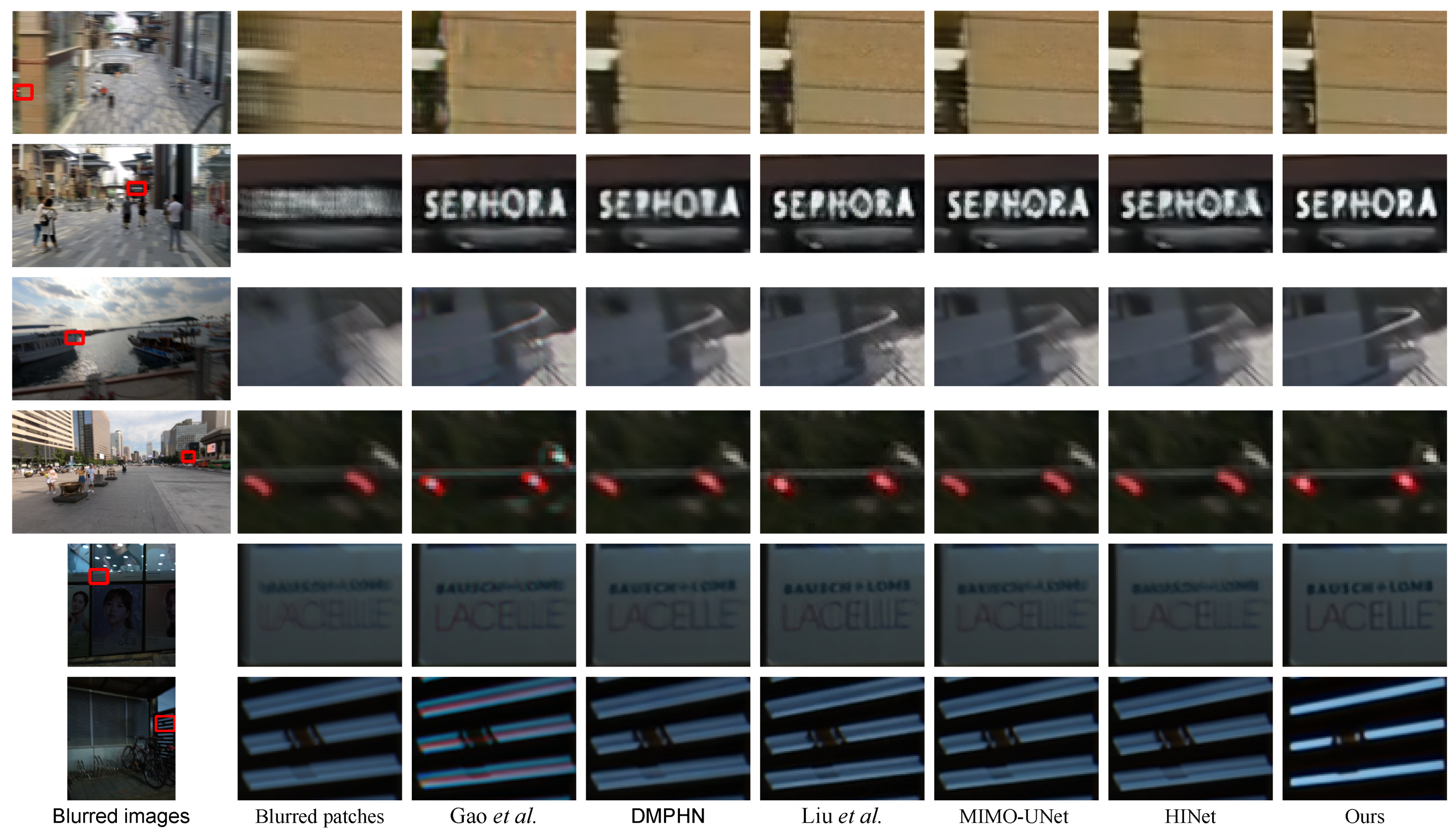

4.3.2. Qualitative Evaluations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, L.; Sun, J.; Quan, L.; Shum, H.Y. Image deblurring with blurred/noisy image pairs. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2007 Papers; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2007; p. 1-es. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, W.; Yu, F. An efficient image reconstruction framework using total variation regularization with LP-quasinorm and group gradient sparsity. Information 2019, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovhannisyan, S.; Agaian, S.; Panetta, K.; Grigoryan, A. Thermal Video Enhancement Mamba: A Novel Approach to Thermal Video Enhancement for Real-World Applications. Information 2025, 16, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Q.; Jia, J.; Agarwala, A. High-quality motion deblurring from a single image. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2008, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, C.J.; Hirsch, M.; Harmeling, S.; Schölkopf, B. Learning to deblur. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 38, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, A. A neural approach to blind motion deblurring. In European Conference on Computer Vision, Proceedings of the 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, S.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, K.M. Deep Multi-scale Convolutional Neural Network for Dynamic Scene Deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Gao, H.; Shen, X.; Wang, J.; Jia, J. Scale-Recurrent Network for Deep Image Deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 8174–8182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Wang, W.; Lu, X.; Shen, J.; Ling, H.; Xu, T.; Shao, L. Human-Aware Motion Deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 5571–5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Tao, X.; Shen, X.; Jia, J. Dynamic Scene Deblurring with Parameter Selective Sharing and Nested Skip Connections. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3843–3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, F.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Sheng, Y.; Zhang, G. Multi-scale Grid Network for Image Deblurring with High-frequency Guidance. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2021, 24, 2890–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dai, Y.; Li, H.; Koniusz, P. Deep Stacked Hierarchical Multi-Patch Network for Image Deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 5971–5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suin, M.; Purohit, K.; Rajagopalan, A. Spatially-attentive patch-hierarchical network for adaptive motion deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 3606–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ren, W.; Yu, K.; Zhang, K.; Cao, X.; Liu, W.; Menze, B. Pyramid architecture search for real-time image deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 4298–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, K.; Rajagopalan, A.N. Region-Adaptive Dense Network for Efficient Motion Deblurring. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 11882–11889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J.; Ji, S.W.; Hong, J.P.; Jung, S.W.; Ko, S.J. Rethinking coarse-to-fine approach in single image deblurring. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 4641–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lu, X.; Zhang, J.; Chu, X.; Chen, C. Hinet: Half instance normalization network for image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Yu, C. Multi-stage attentive network for motion deblurring via binary cross-entropy loss. Entropy 2022, 24, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Wang, Q.; Dai, H.N.; Li, P. Multi-stage feature-fusion dense network for motion deblurring. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2023, 90, 103717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Shen, C.; Yang, Y.B. Image restoration using very deep convolutional encoder-decoder networks with symmetric skip connections. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, F.J.; Peng, Y.T.; Tsai, C.C.; Lin, Y.Y.; Lin, C.W. BANet: A blur-aware attention network for dynamic scene deblurring. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 6789–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Liang, Z.; Gan, Y.; Zhong, J. A novel copy-move forgery detection algorithm via two-stage filtering. Digit. Signal Process. 2021, 113, 103032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.L.; Gan, Y.F.; Vong, C.M.; Yang, J.X.; Zhao, J.H.; Luo, J.H. Effective and efficient pixel-level detection for diverse video copy-move forgery types. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 122, 108286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.F.; Yang, J.X.; Zhong, J.L. Video Surveillance Object Forgery Detection using PDCL Network with Residual-based Steganalysis Feature. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2023, 2023, 8378073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; He, D.; Wang, H.; Qu, Q.; Shan, C.; Zhu, X.; Zhong, J.; Gao, P. Attenuated color channel adaptive correction and bilateral weight fusion for underwater image enhancement. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2025, 184, 108575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, W.; Wang, H.; Gao, P.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X. A fusion framework with multi-scale convolution and triple-branch cascaded transformer for underwater image enhancement. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2025, 184, 108640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wang, Q.; Dai, H.N.; Wang, H.; Li, P. LNNet: Lightweight nested network for motion deblurring. J. Syst. Archit. 2022, 129, 102584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Albanie, S.; Sun, G.; Wu, E. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 42, 2011–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.; Gupta, A.; He, K. Non-local Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7794–7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, K.; Loy, C.C.; Lin, D. Prime Sample Attention in Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11580–11588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Bao, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lu, H. Dual Attention Network for Scene Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3141–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wei, Y.; Huang, L.; Shi, H.; Liu, W.; Huang, T.S. CCNet: Criss-Cross Attention for Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 45, 6896–6908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.S.; Huang, J.B.; Ahuja, N.; Yang, M.H. Deep laplacian pyramid networks for fast and accurate super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nah, S.; Baik, S.; Hong, S.; Moon, G.; Son, S.; Timofte, R.; Mu Lee, K. Ntire 2019 challenge on video deblurring and super-resolution: Dataset and study. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–17 June 2019; pp. 1996–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, J.; Lee, H.; Won, J.; Cho, S. Real-world blur dataset for learning and benchmarking deblurring algorithms. In European Conference on Computer Vision, Proceedings of the 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; Noordhuis, P.; Wesolowski, L.; Kyrola, A.; Tulloch, A.; Jia, Y.; He, K. Accurate, large minibatch sgd: Training imagenet in 1 hour. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.02677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Models | PSNR | SSIM | Model Size | FLOPs | Inference Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSCNet-R2 | 31.72 | 0.951 | 23.10 MB | 67.05 G | 171 ms |

| FSCNet-R3 | 32.23 | 0.955 | 31.91 MB | 98.55 G | 228 ms |

| FSCNet-R4 | 32.48 | 0.958 | 40.73 MB | 130.05 G | 287 ms |

| FSCNet-R5 | 32.75 | 0.960 | 49.54 MB | 161.55 G | 346 ms |

| FSCNet-R6 | 32.83 | 0.960 | 58.36 MB | 193.05 G | 405 ms |

| FSCNet-R7 | 33.01 | 0.962 | 67.18 MB | 224.54 G | 461 ms |

| FSCNet-R8 | 33.03 | 0.962 | 75.99 MB | 256.04 G | 523 ms |

| Models | FCFF | FCFF with SABs | Last Stage with SABs | PSNR | SSIM | Model Size | FLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 32.78 | 0.960 | 66.00 MB | 223.60 G |

| M2 | ✔ | ✗ | ✗ | 32.91 | 0.961 | 66.60 MB | 224.20 G |

| M3 | ✔ | ✗ | ✔ | 32.96 | 0.961 | 66.64 MB | 224.34 G |

| M4 | ✔ | ✔ | ✗ | 32.98 | 0.961 | 67.13 MB | 224.41 G |

| FSCNet | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 33.01 | 0.962 | 67.18 MB | 224.54 G |

| Models | PSNR | SSIM | Model Size | FLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAB uses CBAM | 32.60 | 0.959 | 66.66 MB | 224.21 G |

| SAB uses CWSA | 33.01 | 0.962 | 67.18 MB | 224.54 G |

| Models | GoPro | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR | SSIM | Model Size | FLOPs | Inference Time | |

| SRNDeblur [8] | 30.20 | 0.933 | 32.26 MB | 536.93 G | 672 ms |

| Gao et al. [10] | 30.96 | 0.942 | 46.46 MB | 471.36 G | 575 ms |

| DMPHN [12] | 31.39 | 0.948 | 86.90 MB | 128.80 G | 765 ms |

| RADN [15] | 31.82 | 0.953 | - | - | - |

| Liu et al. [11] | 31.85 | 0.951 | 108.33 MB | 280.46 G | 625 ms |

| Suin et al. [13] | 32.02 | 0.953 | - | - | - |

| MIMO-UNet [16] | 32.44 | 0.957 | 64.59 MB | 150.11 G | 359 ms |

| HINet [17] | 32.77 | 0.959 | 354.71 MB | 153.52 G | 256 ms |

| FSCNet (Ours) | 33.01 | 0.962 | 67.18 MB | 224.54 G | 461 ms |

| Metric | DMPHN [12] | MIMO-UNet [16] | HINet [17] | FSCNet (Ours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPIPS | 0.082 | 0.062 | 0.060 | 0.058 |

| Models | HIDE | REDS | RealBlur-R | RealBlur-J | Weighted Avg | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | |

| SRNDeblur [8] | 28.36 | 0.902 | 26.84 | 0.873 | 35.27 | 0.937 | 28.48 | 0.861 | 28.69 | 0.889 |

| Gao et al. [10] | 29.11 | 0.913 | 26.89 | 0.873 | 35.39 | 0.938 | 28.39 | 0.859 | 28.94 | 0.892 |

| DMPHN [12] | 29.10 | 0.918 | 26.15 | 0.851 | 35.48 | 0.947 | 27.80 | 0.847 | 28.55 | 0.883 |

| Liu et al. [11] | 29.48 | 0.920 | 26.73 | 0.858 | 35.40 | 0.934 | 28.31 | 0.854 | 28.97 | 0.886 |

| MIMO-UNet [16] | 29.99 | 0.930 | 26.43 | 0.859 | 35.54 | 0.947 | 27.64 | 0.837 | 28.91 | 0.889 |

| HINet [17] | 30.33 | 0.932 | 26.87 | 0.867 | 35.75 | 0.950 | 28.17 | 0.849 | 29.30 | 0.895 |

| FSCNet (Ours) | 30.64 | 0.937 | 27.00 | 0.873 | 35.87 | 0.953 | 28.67 | 0.872 | 29.53 | 0.903 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, Y.; Tao, B.; Wang, Q.; Mai, G.; Guo, C. Fully-Cascaded Spatial-Aware Convolutional Network for Motion Deblurring. Information 2025, 16, 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121055

Hong Y, Tao B, Wang Q, Mai G, Guo C. Fully-Cascaded Spatial-Aware Convolutional Network for Motion Deblurring. Information. 2025; 16(12):1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121055

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Yinghan, Bishenghui Tao, Qian Wang, Guizhen Mai, and Cai Guo. 2025. "Fully-Cascaded Spatial-Aware Convolutional Network for Motion Deblurring" Information 16, no. 12: 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121055

APA StyleHong, Y., Tao, B., Wang, Q., Mai, G., & Guo, C. (2025). Fully-Cascaded Spatial-Aware Convolutional Network for Motion Deblurring. Information, 16(12), 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121055