Exploring the Paradigm of Enterprise Data Protection: Constructing Enterprise Data Rights Under the Rightification of Behavioral Regulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research Trends and Examination of the “Technical Control Paradigm”

2.2. Research Trends and Review of the “Behavioral Regulation Paradigm”

2.3. Research Trends and Examination of the “Rights Protection Paradigm”

2.3.1. Review of Property Rights Protection Paradigms for Enterprise Data

2.3.2. Review of Intellectual Property Protection Paradigms for Enterprise Data

2.3.3. Examination of the Special Property Rights Protection Paradigm for Enterprise Data

3. Method

3.1. Literature Review Method

3.2. Normative Analysis Method

3.3. Case Analysis Method

4. Paradigm Shift: The Explanatory Power of the “Rightification of Behavioral Regulation” Paradigm for Enterprise Data

4.1. Mutual Compatibility Between “Technical Control” and “Legal Control”

4.2. The Interlocking of “Legal Interest Protection” and “Rights Protection”

4.3. The Integration of “Property-Based Rights” and “Usage-Based Rights”

5. Paradigm Construction: Structuring Enterprise Data Rights Under the “Rightification of Behavioral Regulation” Approach

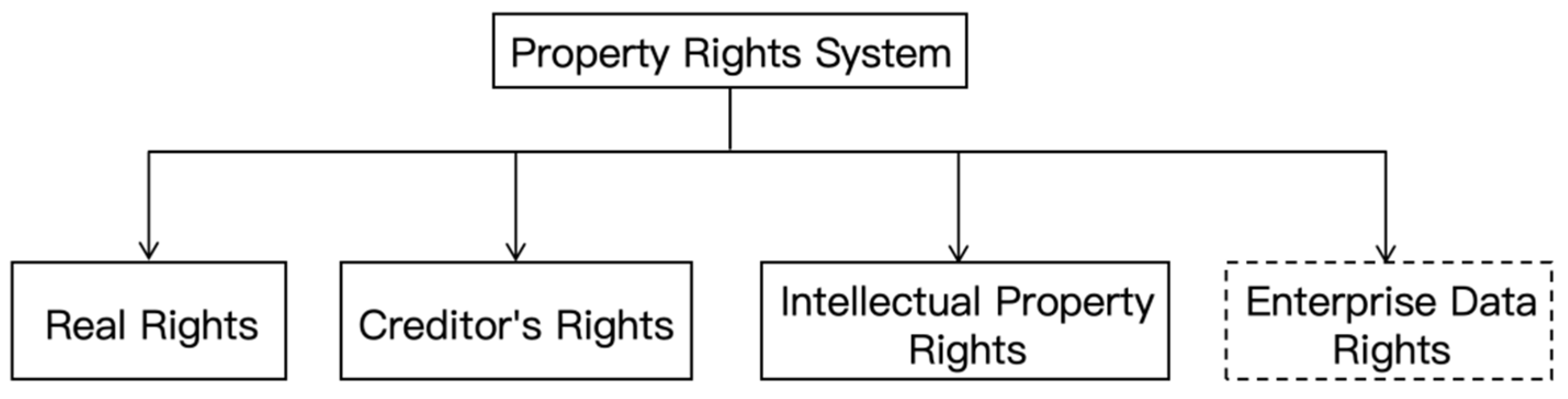

5.1. Positioning Corporate Data Rights Within the System Under the “Rightification of Behavioral Regulation” Approach

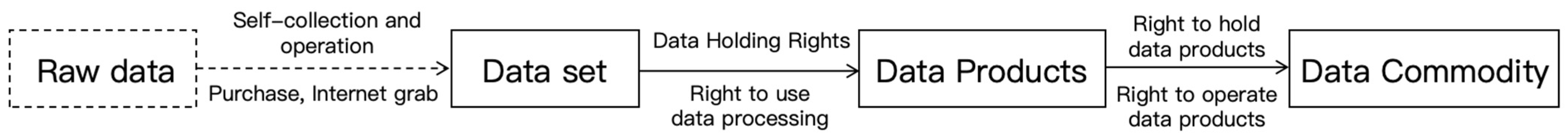

5.2. Defining the Subject Matter of Enterprise Data Rights Under the “Rightification of Behavioral Regulation”

5.3. Specific Functions of Enterprise Data Rights Under the “Rightification of Behavioral Regulation” Approach

5.4. Designing the Functional Combination of Enterprise Data Rights Under the “Rightification of Behavioral Regulation” Approach

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, S.H.; Deng, P. Exploration and Institutional Framework of a Unified Data Property Rights Registration System. E-Government 2024, 12, 28–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, L. Code 2.0: Law in Cyberspace; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.H. The Theoretical Justification of Emerging Rights and the Construction of Emerging Rights in Cyberspace. Soc. Sci. Beijing 2022, 4, 74–84. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.T. Artificial Intelligence and the Rebirth of Human Politics. Probe 2020, 5, 52–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.Z.; Yong, Q. From Embedding to Convergence: The Relationshipand Optimization between Technological Governance and Legal Governance. Acad. Mon. 2024, 12, 100–111. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.S.; Gao, Y. The Systemic Composition and New Characteristics of Digital Rights A Theoretical Analysis from the Perspective of Information Flow. Wuhan Univ. J. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2025, 3, 51–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S. Reinterpretation of the Statutory Principle of Intellectual Property Rights. Contemp. Law Rev. 2018, 6, 60–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S. The Concept Restoration and System Integration of Intellectual Property Law from the Perspective of Legal Interest Protection Theory. Zhejiang Acad. J. 2021, 4, 85–94. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.D. Behavioral Protection of New Data Property: Analysis Based on Property Rights Theory. Law Sci. Mag. 2023, 2, 54–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Behavior Regulation Mode for Copyright Protection of AI-generated Content—Taking Sora as an Example. Journal. Mass Commun. 2024, 6, 59–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.Q. The Merits and Shortcomings of the “Civil Rights Chapter” in the General Provisions of the Civil Code. Peking Univ. Law J. 2017, 3, 645–655. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C. Behavior Regulation Model of Enterprise Data Rights Protection and Application. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. Soc. Sci. 2022, 6, 84–92. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y. Reflection and Transformation of the Legal Path of Data Governance. Sci. Law J. Northwest Univ. Political Sci. Law 2020, 2, 79–89. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Li, Y.N. Path Selection for Data Protection. Academics 2018, 7, 52–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, C. Judgment Rules of Unfair Competition Cases Concerning Data. People’s Judic. 2019, 10, 16–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.J. The Civil Law Interpretation and Protection Methods of Personal Information. Law Sci. 2021, 3, 116–130. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.J. General Principles of Civil Law; China Legal Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K. Three Approaches to Data Protection: Comment on the Case of Weibo Accusing Maimai of Unfair Competition. J. Shanghai Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2017, 6, 15–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.X. On Data Usufruct. Soc. Sci. China 2020, 11, 110–131. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C.C. Jurisprudential Foundation and Institutional Framework for the Initial Configuration of Data Rights. Sci. Law J. Northwest Univ. Political Sci. Law 2024, 4, 105–113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.M. On Data Rights and Interests: From the Perspective of Bundle of Rights. Political Sci. Law 2022, 7, 99–113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.Q. On the Construction of New Data Property and its System Structure. Trib. Political Sci. Law 2017, 4, 63–77. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.Y. Theory of Structure of Mother Right-Child Right and Its Significance. J. Henan Univ. Econ. Law 2012, 2, 9–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.D. From “Separation of Powers” to “Exercise of Rights”. Soc. Sci. China 2021, 4, 87–206. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.H. A Critic of the Theory on Enterprise Data Property Rights Protection. Orient. Law 2022, 2, 132–143. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Wang, N. The Justification and Construction of “Bi-level Dual Structure” on Data Property Right. China Law Rev. 2023, 6, 138–156. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.D. On Legal Protection of Enterprises’ Data: Analysis Based on the Legal Nature of Data. Sci. Law J. Northwest Univ. Political Sci. Law 2020, 2, 90–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.Q. On the Property Law Protection of Company Data. Orient. Law 2018, 3, 50–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.P. Justification and Rules of Data Intellectual Property Rights. Law Soc. Dev. 2024, 4, 205–224. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.N. Establishing and Improving the Data Intellectual Property Rights System. Guangming Daily, 28 March 2025; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. On Theoretical Proof and Normative Construction for Intellectual Property Protection of Enterprise Data. China Law Rev. 2023, 2, 38–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.X.; Chen, X.J. Derivative Data Constitutes the Subject Matter of Data Proprietary Rights. China Social Sciences News, 13 July 2016; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, D.M. Can “Data” be Integrated into the Category of Objects of Intellectual Property Rights? J. Political Sci. Law 2024, 1, 137–148. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.M.; Dai, M.M. Research on Rights Attributes and Legal Protection of Big Data Products. J. Zhejiang Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2020, 2, 26–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.F. The Institutional Guarantee of Social Innovation with Regards to China’s “Big Data Strategy”—From the Perspective of Intellectual Property Rights. J. Nanjing Univ. Sci. Technol. Soc. Sci. 2019, 3, 27–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Z.Y. On the Construction of Data Property Right. Jurist 2021, 6, 75–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.B. On Data Property Rights as a New Type of Property Right. Soc. Sci. China 2023, 4, 144–163. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.L.; Cai, X.X. Digital Economy and the Legal Protection of Enterprise Data Property. Trib. Soc. Sci. 2023, 4, 180–191. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Smith, H.E. An economic analysis of civil versus common law property. Notre Dame L. Rev. 2012, 88, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne. Human Rights and Diversity—Philosophy of Human Rights; Xia, Y., Zhang, Z., Translators; Encyclopedia of China Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1995; p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.E. Exclusion versus Governance: Two Strategies for Delineating Property Rights. J. Leg. Stud. 2002, 31, 453–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L. An Interpretation of the System of the Tri-Right Separation of Data: Underlying Logic, Jurisprudential Reflection, and Legal Realization. J. Beijing Adm. Inst. 2024, 6, 76–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K. From Bundle of Rights to Right as Modularity: Reflection and Reconstruction of the Separation of Three Rights in Data. China Law Rev. 2023, 2, 22–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Yu, Z.Y. Rethinking Competitive Relationship and Reconsidering the Pathof Anti-Unfair Competition Law for Data Rights Confirmation. Sci. Technol. Law Chin.-Engl. Version 2024, 5, 25–36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Genealogy of Property Rights,Numerus Clausus of Property Rights and Property Law in General of Civil Law. Trib. Political Sci. Law 2016, 1, 103–118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Z.Q. Theoretical Justification and Normative Construction of the Protection of Environmental Right Under Law of Intellectual Property. Law Sci. 2022, 8, 177–192. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt, M.; Kerber, W. Property rights theory, bundles of rights on IoT data, and the EU Data Act. Eur. J. Law Econ. 2024, 57, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.Q. General Principles of Civil Law, 2nd ed; China Legal Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.H. Absolute Rights,Absolute Duties and their Relativization A Unified Framework for Protection of Civil Rights and Legal Interests. Peking Univ. Law J. 2023, 3, 646–667. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Cheng, Z.R. Behavioral Regulation Models for the Protection of Data Property Interests. J. Zhengzhou Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2023, 6, 44–53+139. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hohfeld, W.N. Fundamental legal conceptions as applied in judicial reasoning. Yale Law J. 1917, 26, 710–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.X.; Huang, Y.B. On the Historical Origin and Realistic Implications of the Bundle of Rights. Dongyue Trib. 2025, 6, 68–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.W. On the Data Entitlement Framework: From Object to Model. J. Comp. Law 2024, 2, 135–148. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.X. On the hierarchical nature of data property rights system: “Three Three System” Data Rights Confirmation Law. China Leg. Sci. 2023, 4, 26–48. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.Y. The Legislative Expression of the Principle of Numerus Clausus. ECUPL J. 2019, 5, 106–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.X. Restructuring Reproduction Rights: Legal Path for Data Training in Generative Artificial Intelligence. Orient. Law 2024, 6, 70–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, X.Z. Constructing a System for the Fair Use of Enterprise Data Rights. Inn. Mong. Soc. Sci. 2025, 2, 108–117+213. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.M. Property Rights Legislation: Adopting Property Rights or Property Rights. People’s Court Daily, 27 August 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, K.K. The constituent elements of the theory of distinction between creditor’s rights and real rights. Chin. J. Law 2005, 1, 20–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.D. The Categorization, Institutionalization and Codification of Property Right: Taking the Draft of Civil Code as the Research Subject. Mod. Law Sci. 2017, 3, 31–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.M. Data Rights and Interests Expression Civil Law. Jingchu Law Rev. 2024, 1, 19–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qi, A.M. On the Legal Protection of Information Property and the Establishment of the Property Right System in the Civil Law System: Also on the Relationship within Property Law, intellectual property law and information property law. Acad. Forum 2009, 2, 145–152. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.E. The Legal Nature and Sectional Protection of Data Rights. Theory Mon. 2020, 3, 113–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. Research on the Mechanism for the Ownership and Authorization of Corporate Data Rights. J. Comp. Law 2020, 3, 56–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.W. Research on Local Policies in China for Data Rights Confirmation and Registration from the Perspective of Enterprise Data Assetization. J. Inf. Resour. Manag. 2024, 6, 85–98. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.M. Civil Law; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2005; p. 309. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.Y. Civil Law; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2000; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.X. Legal Analysis on the Power Structure of Intellectual Property. Res. Rule Law 2014, 7, 112–119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.E. General Principles of Civil Law (Volume I); China Law Press: Beijing, China, 2005; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, X.P. The Effective Utilization of Data as a Factor of Production Requires a Proper Understanding of the Fundamental Connotation of Data Resource Holding Rights. Science and Technology Daily, 5 September 2022; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.K.; Zhou, X.J. Ownership of Data Resources: Generative Logic, Institutional Positioning, and Operation Paradigm. J. Yanbian Univ. Soc. Sci. 2024, 3, 85–99+143. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.S. The Construction of Data Holder’s Right under Possession Theory. Jinan J. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2023, 4, 50–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.P. Rights Allocation of Data Holders:Legal Implementation of Structural Separation of Data Property Rights. J. Comp. Law 2023, 3, 26–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B. The Discomfort of Dividing Data Property Rights—Turning to Data Ownership Based on Module Theory. Orient. Law 2024, 1, 47–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.P. On Data Holder’s Right Towards a New Paradigm to Achieve Orderly Data Flow. Peking Univ. Law J. 2023, 2, 307–327. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.H. The Data Holding Right. ECUPL J. 2025, 2, 6–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shang, J.G. Chinese Solution for the Allocation of Data Element Rights and Interests. J. Shanghai Norm. Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2023, 3, 82–94. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.C.; Chen, R.K. Legal Interpretation of Data Resource Holding Rights. Sci. Technol. Law Chin.-Engl. Version 2024, 2, 21–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y. Interest Construction and Institutional Safeguards for the Right to Operate Data Products. Digit. Law 2024, 4, 56–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ji, L.L. The Judicial Dilemma of Enterprise Data Protection and the Dimension of Breaking the Situation: The Road to Typed Right Confirmation. Leg. Forum 2022, 3, 109–121. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, R. On Intellectual Property Protection of Enterprise Data. Soc. Sci. Shenzhen 2024, 2, 75–88. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, Y. Modern Japanese Intellectual Property Law Theory; China Law Press: Beijing, China, 2010; p. 7, Li, Y., et al., Translators. Available online: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E6%97%A5%E6%9C%AC%E7%8E%B0%E4%BB%A3%E7%9F%A5%E8%AF%86%E4%BA%A7%E6%9D%83%E6%B3%95%E7%90%86%E8%AE%BA/570268 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Lv, B.B. Justifying the Right to Personal Information as a Civil Right:Taking Intellectual Property as the Reference. China Leg. Sci. 2019, 4, 44–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Li, D. The Right Explanation and Legal Expression of the Data Property Right Separation. J. Guangxi Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2024, 1, 183–193. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y. From Data Production to Data Circulation: A Double-layer Allocation Scheme for Data Property Rights. Chin. J. Law 2023, 3, 73–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J. Forming an Autonomous Digital Jurisprudence Theory. Guangming Daily (Theory Edition), 16 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Case Name | Case Number | Case Impact | Judicial Characterization of Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dianping v. Aibang | Beijing No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court (2011) Yizhong Minzhong No. 7512 | China’s First Case Involving Local Search Platforms | Competitive Property Rights in Data Aggregates |

| Sina v. Maimai Case | Beijing Intellectual Property Court (2016) Jing 73 Min Zhong No. 588 | China’s First Unfair Competition Case Involving Big Data | Competitive Property Rights in User Data Information |

| Taobao v. Meijing | Hangzhou Intermediate People’s Court of Zhejiang Province (2018) Zhe 01 Min Zhong No. 7312 | China’s First Unfair Competition Case Involving Big Data Products | Data Products Possess Competitive Property Rights Interests but Do Not Constitute Property Ownership |

| KuMiKe App v. CheLaiLe App Unfair Competition Case | Hangzhou Binjiang District People’s Court (2019) Zhe 0108 Min Chu No. 5049 | China’s First “Web Crawler” Software Case | Intangible Property and Competitive Interests in Data Collections |

| Tencent v. Juketong Company et al. Unfair Competition Case | Hangzhou Binjiang District People’s Court (2019) Zhe 0108 Min Chu 5049 | China’s First Unfair Competition Case Involving Recognition of WeChat Data Rights | User Information Possesses Data Rights of Different Natures. |

| Ant Microloan v. Suzhou Langdong Network Technology | Hangzhou Intermediate People’s Court, Zhejiang Province (2020) Zhe 01 Min Zhong 4847 | China’s First Unfair Competition Case Involving Public Data | Competitive Rights in Public Data |

| Douyin v. Liujie | Hangzhou Intermediate People’s Court, Zhejiang Province (2020) Zhe 01 Min Zhong 4847 | China’s First Live Streaming Data Rights Case | Competitive Property Rights in Live Streaming Data |

| Specific Rights Framework | Basic Characteristics | Protection Model |

|---|---|---|

| Property Rights Framework | Intertwined “Separation of Rights and Exercising of Rights” | Ownership Protection Model |

| Data Exclusive Rights Protection Model | ||

| Multi-tier Usufruct Rights Model | ||

| Intellectual Property System | The Clash Between Traditional and Emerging Rights | Traditional Intellectual Property |

| Emerging Intellectual Property Rights | ||

| Scenario-Based Protection of Intellectual Property | ||

| Data-Specific Property Rights | The Interplay Between “Full Property Rights and Limited Property Rights” | Specialized Property Rights |

| Separate Property Rights |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, X.; Ding, W.; Fu, D. Exploring the Paradigm of Enterprise Data Protection: Constructing Enterprise Data Rights Under the Rightification of Behavioral Regulation. Information 2025, 16, 1028. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121028

Hu X, Ding W, Fu D. Exploring the Paradigm of Enterprise Data Protection: Constructing Enterprise Data Rights Under the Rightification of Behavioral Regulation. Information. 2025; 16(12):1028. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121028

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Xiaowei, Wen Ding, and Deqian Fu. 2025. "Exploring the Paradigm of Enterprise Data Protection: Constructing Enterprise Data Rights Under the Rightification of Behavioral Regulation" Information 16, no. 12: 1028. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121028

APA StyleHu, X., Ding, W., & Fu, D. (2025). Exploring the Paradigm of Enterprise Data Protection: Constructing Enterprise Data Rights Under the Rightification of Behavioral Regulation. Information, 16(12), 1028. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16121028