Reference-Less Evaluation of Machine Translation: Navigating Through the Resource-Scarce Scenarios

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Quality Estimation

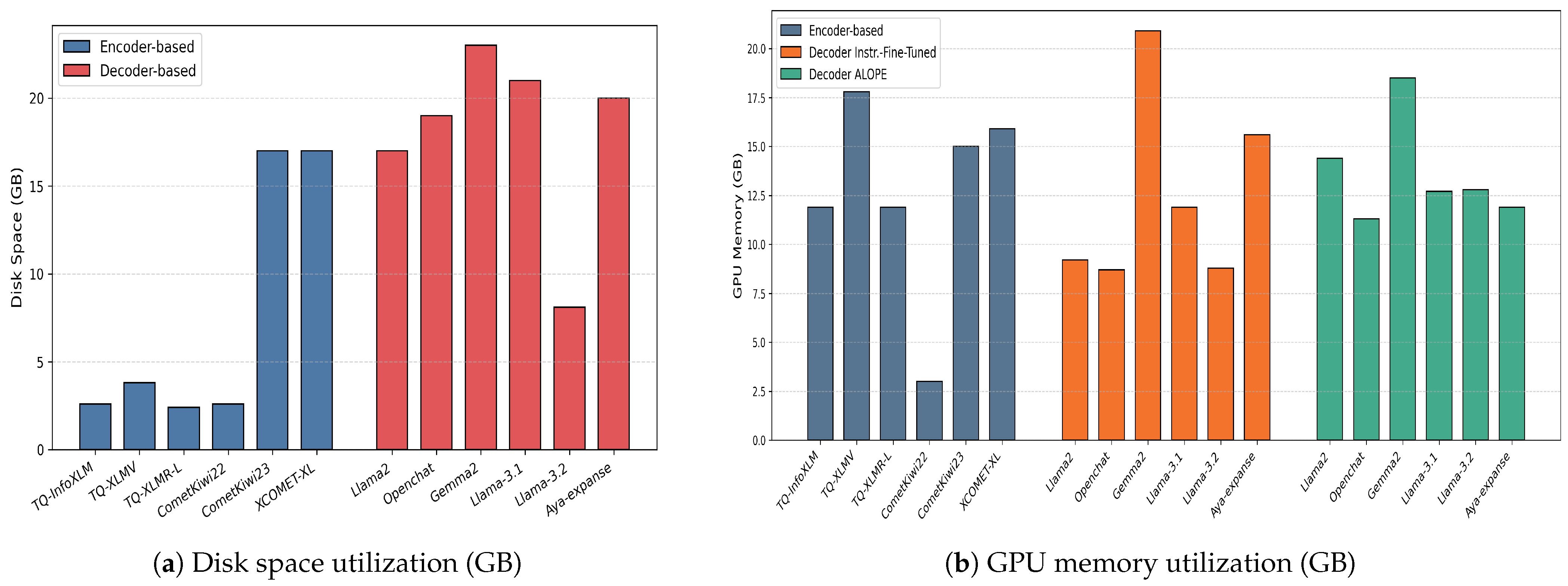

2.2. Encoder- and Decoder-Based Language Models

2.3. Direct Assessment Scores (DA Scores)

3. Data

4. Methods

4.1. Encoder-Based Methods

4.1.1. TransQuest

4.1.2. CometKiwi

4.1.3. xCOMET

4.2. Decoder-Based Methods

4.2.1. Instruction-Fine-Tuned LLMs for QE

4.2.2. TOWER+

4.2.3. ALOPE

5. Experiment Setup

6. Results and Discussion

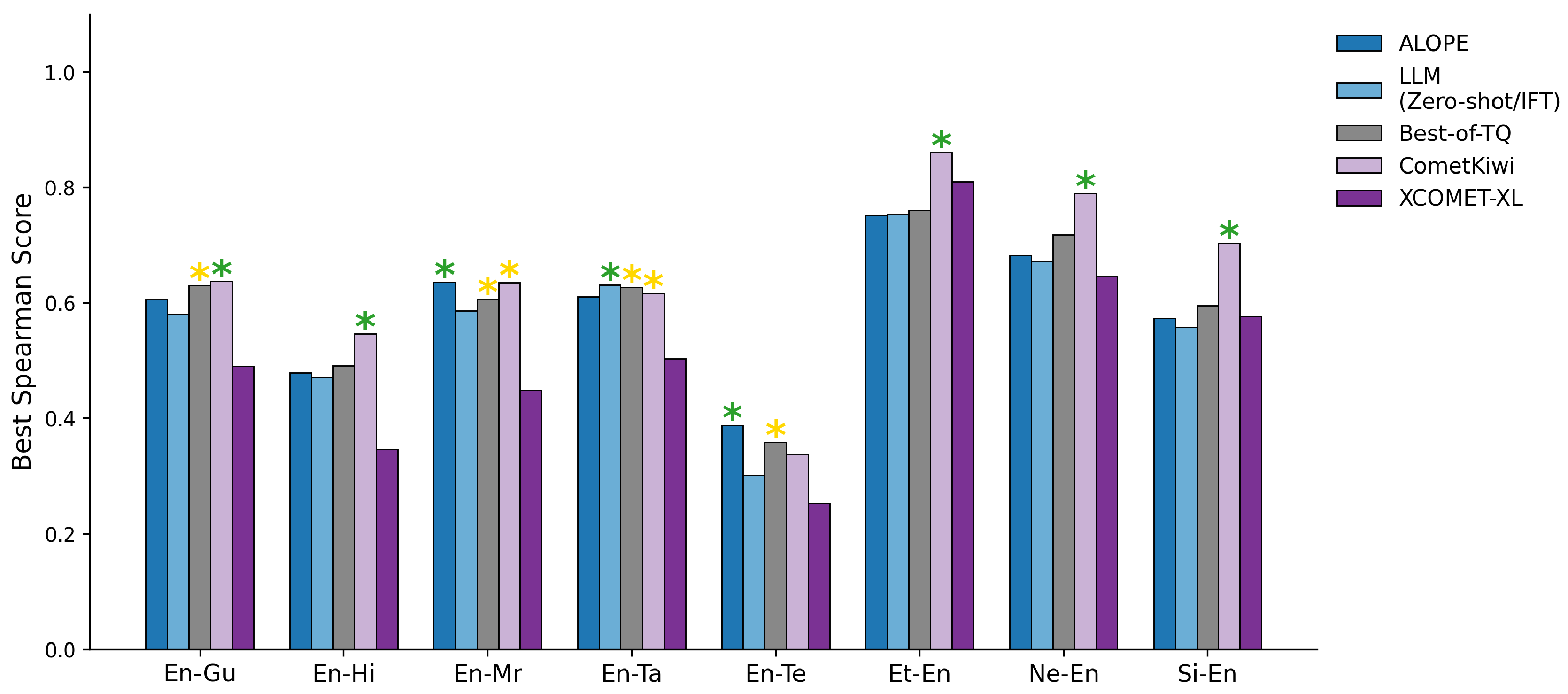

6.1. Encoder-Based

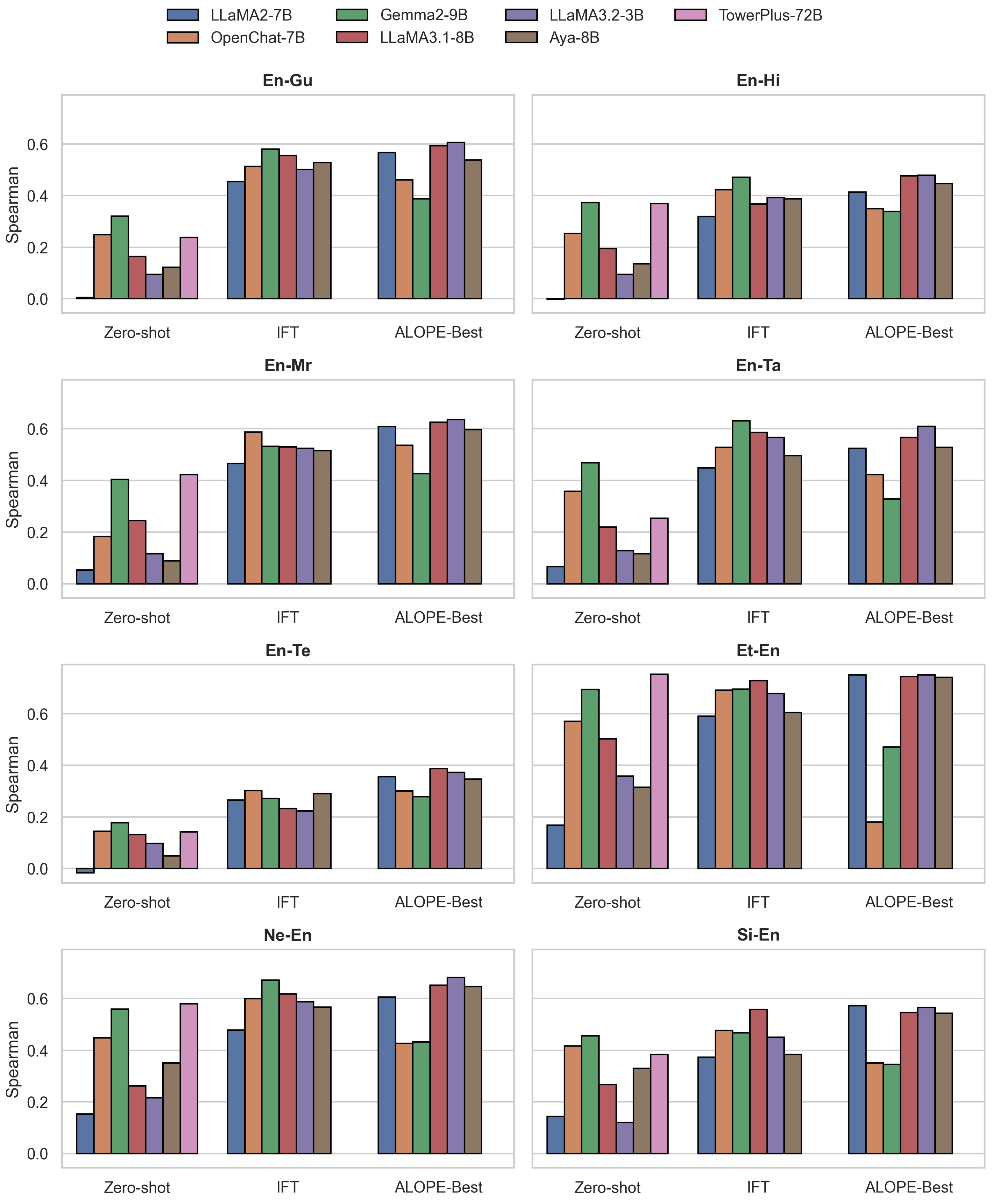

6.2. Decoder-Based

6.3. Comparative Analysis: Encoder vs. Decoder

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MT | Machine Translation |

| DA | Direct Assessment |

| QE | Quality Estimation |

| ALOPE | The Adaptive Layer Optimization for Translation Quality Estimation |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| MQM | Multidimensional Quality Metrics |

Appendix A. Experiment Results of ALOPE with Additional Transformer Layers

| TL | Model | En-Gu | En-Hi | En-Mr | En-Ta | En-Te | Et-En | Ne-En | Si-En |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL (-11) | Llama-2-7B | 0.360 | 0.301 | 0.361 | 0.254 | 0.293 | 0.405 | 0.164 | 0.049 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.514 | 0.412 | 0.609 | 0.438 | 0.304 | 0.148 | 0.554 | 0.493 | |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.594 | 0.476 | 0.605 | 0.610 | 0.373 | 0.748 | 0.678 | 0.560 | |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.490 | 0.411 | 0.572 | 0.445 | 0.336 | 0.569 | 0.453 | 0.439 | |

| TL (-20) | Llama-2-7B | 0.470 | 0.405 | 0.544 | 0.460 | 0.338 | 0.684 | 0.508 | 0.534 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.484 | 0.394 | 0.553 | 0.321 | 0.172 | 0.649 | 0.524 | 0.494 | |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.430 | 0.408 | 0.579 | 0.303 | 0.286 | 0.601 | 0.488 | 0.464 | |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.437 | 0.300 | 0.488 | 0.263 | 0.287 | 0.483 | 0.438 | 0.395 | |

| TL (-24) | Llama-2-7B | 0.500 | 0.421 | 0.538 | 0.379 | 0.239 | 0.630 | 0.507 | 0.472 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.421 | 0.378 | 0.552 | 0.330 | 0.290 | 0.515 | 0.530 | 0.464 | |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.443 | 0.376 | 0.507 | 0.367 | 0.299 | 0.559 | 0.528 | 0.487 | |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.375 | 0.319 | 0.440 | 0.337 | 0.220 | 0.393 | 0.407 | 0.345 |

Appendix B. Pearson’s and Kendall’s Tau Correlation Scores of Encoder-Based QE Approaches

| Model | En-Gu | En-Hi | En-Mr | En-Ta | En-Te | Et-En | Ne-En | Si-En | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MonoTQ-InfoXLM | 0.680 | 0.460 | 0.610 | 0.336 | 0.658 | 0.434 | 0.650 | 0.435 | 0.330 | 0.247 | 0.755 | 0.560 | 0.767 | 0.530 | 0.627 | 0.413 |

| MonoTQ-XLM-V | 0.586 | 0.396 | 0.518 | 0.312 | 0.608 | 0.389 | 0.654 | 0.435 | 0.312 | 0.246 | 0.764 | 0.565 | 0.743 | 0.517 | 0.643 | 0.425 |

| MonoTQ-XLM-R-XL | 0.652 | 0.432 | 0.617 | 0.346 | 0.489 | 0.317 | 0.690 | 0.454 | 0.292 | 0.230 | 0.729 | 0.536 | 0.727 | 0.514 | 0.607 | 0.409 |

| CometKiwi-22 | 0.615 | 0.416 | 0.511 | 0.283 | 0.717 | 0.449 | 0.601 | 0.404 | 0.233 | 0.162 | 0.807 | 0.624 | 0.750 | 0.566 | 0.678 | 0.469 |

| CometKiwi-23 | 0.678 | 0.467 | 0.618 | 0.390 | 0.711 | 0.455 | 0.648 | 0.446 | 0.310 | 0.235 | 0.852 | 0.661 | 0.783 | 0.599 | 0.730 | 0.515 |

| xCOMET-XL | 0.517 | 0.351 | 0.305 | 0.235 | 0.439 | 0.304 | 0.443 | 0.357 | 0.213 | 0.174 | 0.771 | 0.609 | 0.705 | 0.467 | 0.597 | 0.409 |

Appendix C. Pearson’s and Kendall’s Tau Correlation Scores of Decoder-Based QE Approaches

| Model | En-Gu | En-Hi | En-Mr | En-Ta | En-Te | Et-En | Ne-En | Si-En | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-shot | ||||||||||||||||

| Llama-2-7B | 0.015 | 0.005 | −0.031 | −0.001 | 0.054 | 0.042 | 0.034 | 0.054 | 0.005 | −0.013 | 0.173 | 0.129 | 0.144 | 0.119 | 0.155 | 0.113 |

| OpenChat-7B | 0.267 | 0.187 | 0.315 | 0.188 | 0.323 | 0.137 | 0.400 | 0.270 | 0.155 | 0.109 | 0.550 | 0.411 | 0.476 | 0.320 | 0.439 | 0.299 |

| Gemma-2-9B | 0.093 | 0.254 | 0.482 | 0.289 | 0.430 | 0.311 | 0.400 | 0.353 | 0.052 | 0.134 | 0.620 | 0.524 | 0.329 | 0.416 | 0.427 | 0.332 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.183 | 0.115 | 0.261 | 0.135 | 0.289 | 0.171 | 0.254 | 0.152 | 0.153 | 0.092 | 0.500 | 0.354 | 0.333 | 0.191 | 0.291 | 0.190 |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.100 | 0.068 | 0.148 | 0.067 | 0.163 | 0.084 | 0.128 | 0.091 | 0.082 | 0.071 | 0.355 | 0.255 | 0.231 | 0.155 | 0.136 | 0.085 |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.013 | 0.096 | 0.055 | 0.102 | 0.027 | 0.069 | −0.047 | 0.088 | −0.006 | 0.038 | 0.240 | 0.229 | 0.299 | 0.259 | 0.309 | 0.240 |

| Tower+-72B | 0.278 | 0.184 | 0.478 | 0.286 | 0.500 | 0.322 | 0.386 | 0.189 | 0.156 | 0.106 | 0.754 | 0.586 | 0.604 | 0.462 | 0.368 | 0.296 |

| Instruction Fine-Tuning | ||||||||||||||||

| Llama-2-7B | 0.539 | 0.342 | 0.477 | 0.234 | 0.515 | 0.335 | 0.526 | 0.333 | 0.228 | 0.195 | 0.597 | 0.420 | 0.558 | 0.335 | 0.389 | 0.260 |

| OpenChat-7B | 0.597 | 0.383 | 0.568 | 0.314 | 0.621 | 0.429 | 0.582 | 0.396 | 0.261 | 0.221 | 0.667 | 0.501 | 0.665 | 0.430 | 0.479 | 0.337 |

| Gemma-2-9B | 0.660 | 0.438 | 0.602 | 0.352 | 0.625 | 0.388 | 0.647 | 0.474 | 0.223 | 0.200 | 0.654 | 0.502 | 0.731 | 0.492 | 0.471 | 0.330 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.613 | 0.416 | 0.517 | 0.272 | 0.608 | 0.388 | 0.625 | 0.438 | 0.206 | 0.167 | 0.693 | 0.533 | 0.684 | 0.444 | 0.557 | 0.399 |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.587 | 0.374 | 0.558 | 0.289 | 0.593 | 0.381 | 0.612 | 0.424 | 0.177 | 0.162 | 0.657 | 0.489 | 0.653 | 0.421 | 0.458 | 0.319 |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.624 | 0.396 | 0.532 | 0.287 | 0.591 | 0.373 | 0.560 | 0.368 | 0.221 | 0.209 | 0.587 | 0.431 | 0.653 | 0.409 | 0.385 | 0.271 |

| ALOPE-TL (-1) | ||||||||||||||||

| Llama-2-7B | 0.630 | 0.409 | 0.554 | 0.290 | 0.643 | 0.436 | 0.581 | 0.372 | 0.306 | 0.242 | 0.736 | 0.540 | 0.647 | 0.425 | 0.605 | 0.401 |

| OpenChat-7B | 0.043 | 0.033 | 0.111 | 0.059 | −0.174 | −0.080 | 0.159 | 0.021 | 0.125 | 0.117 | 0.132 | 0.090 | −0.064 | −0.003 | −0.027 | 0.000 |

| Gemma-2-9B | 0.367 | 0.229 | 0.333 | 0.197 | 0.441 | 0.277 | 0.267 | 0.204 | 0.200 | 0.162 | 0.435 | 0.296 | 0.407 | 0.283 | 0.362 | 0.220 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.630 | 0.430 | 0.572 | 0.331 | 0.606 | 0.445 | 0.593 | 0.403 | 0.330 | 0.248 | 0.710 | 0.534 | 0.672 | 0.470 | 0.584 | 0.388 |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.662 | 0.437 | 0.608 | 0.337 | 0.692 | 0.457 | 0.634 | 0.417 | 0.314 | 0.243 | 0.734 | 0.534 | 0.727 | 0.490 | 0.594 | 0.385 |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.086 | 0.047 | 0.172 | 0.123 | 0.284 | 0.148 | 0.039 | −0.006 | 0.231 | 0.190 | 0.105 | 0.077 | 0.048 | 0.007 | 0.080 | 0.051 |

| ALOPE-TL (-7) | ||||||||||||||||

| Llama-2-7B | 0.623 | 0.409 | 0.407 | 0.231 | 0.569 | 0.382 | 0.540 | 0.348 | 0.240 | 0.218 | 0.733 | 0.539 | 0.641 | 0.433 | 0.613 | 0.408 |

| OpenChat-7B | 0.008 | 0.024 | 0.160 | 0.073 | −0.133 | −0.046 | 0.063 | 0.093 | 0.146 | 0.128 | 0.146 | 0.098 | 0.167 | 0.087 | 0.132 | 0.038 |

| Gemma-2-9B | 0.412 | 0.260 | 0.386 | 0.210 | 0.481 | 0.289 | 0.315 | 0.187 | 0.237 | 0.187 | 0.446 | 0.310 | 0.432 | 0.300 | 0.405 | 0.235 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.641 | 0.428 | 0.579 | 0.337 | 0.654 | 0.444 | 0.593 | 0.377 | 0.363 | 0.266 | 0.740 | 0.542 | 0.669 | 0.459 | 0.596 | 0.387 |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.657 | 0.441 | 0.598 | 0.338 | 0.660 | 0.443 | 0.640 | 0.423 | 0.319 | 0.255 | 0.733 | 0.551 | 0.701 | 0.483 | 0.602 | 0.394 |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.608 | 0.388 | 0.576 | 0.312 | 0.615 | 0.426 | 0.588 | 0.374 | 0.301 | 0.240 | 0.727 | 0.539 | 0.671 | 0.470 | 0.582 | 0.386 |

| ALOPE-TL (-16) | ||||||||||||||||

| Llama-2-7B | 0.603 | 0.388 | 0.493 | 0.266 | 0.615 | 0.414 | 0.540 | 0.344 | 0.262 | 0.212 | 0.748 | 0.550 | 0.640 | 0.413 | 0.611 | 0.404 |

| OpenChat-7B | 0.489 | 0.323 | 0.477 | 0.241 | 0.592 | 0.378 | 0.482 | 0.295 | 0.260 | 0.208 | 0.185 | 0.120 | 0.471 | 0.296 | 0.395 | 0.242 |

| Gemma-2-9B | 0.427 | 0.270 | 0.431 | 0.232 | 0.483 | 0.290 | 0.358 | 0.223 | 0.142 | 0.092 | 0.463 | 0.323 | 0.419 | 0.293 | 0.406 | 0.239 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.609 | 0.402 | 0.562 | 0.315 | 0.656 | 0.430 | 0.568 | 0.366 | 0.283 | 0.237 | 0.697 | 0.537 | 0.668 | 0.473 | 0.552 | 0.364 |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.611 | 0.400 | 0.587 | 0.322 | 0.677 | 0.426 | 0.619 | 0.390 | 0.331 | 0.233 | 0.744 | 0.544 | 0.721 | 0.498 | 0.609 | 0.405 |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.552 | 0.333 | 0.522 | 0.268 | 0.611 | 0.392 | 0.560 | 0.337 | 0.271 | 0.215 | 0.724 | 0.528 | 0.656 | 0.410 | 0.580 | 0.383 |

| ALOPE-TL(-11) | ||||||||||||||||

| Llama-2-7B | 0.385 | 0.245 | 0.293 | 0.206 | 0.393 | 0.241 | 0.246 | 0.174 | 0.175 | 0.200 | 0.406 | 0.274 | 0.130 | 0.108 | 0.078 | 0.032 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.565 | 0.367 | 0.546 | 0.288 | 0.615 | 0.436 | 0.530 | 0.304 | 0.282 | 0.206 | 0.141 | 0.100 | 0.590 | 0.396 | 0.533 | 0.346 |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.654 | 0.430 | 0.577 | 0.335 | 0.673 | 0.434 | 0.659 | 0.444 | 0.354 | 0.257 | 0.745 | 0.548 | 0.718 | 0.496 | 0.604 | 0.400 |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.555 | 0.347 | 0.563 | 0.286 | 0.598 | 0.403 | 0.528 | 0.313 | 0.317 | 0.233 | 0.561 | 0.397 | 0.501 | 0.316 | 0.492 | 0.306 |

| ALOPE-TL(-20) | ||||||||||||||||

| Llama-2-7B | 0.485 | 0.329 | 0.465 | 0.277 | 0.600 | 0.383 | 0.480 | 0.317 | 0.262 | 0.232 | 0.647 | 0.488 | 0.537 | 0.358 | 0.560 | 0.378 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.560 | 0.346 | 0.524 | 0.276 | 0.576 | 0.389 | 0.504 | 0.220 | 0.212 | 0.119 | 0.617 | 0.463 | 0.553 | 0.371 | 0.522 | 0.347 |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.487 | 0.304 | 0.508 | 0.281 | 0.604 | 0.410 | 0.475 | 0.207 | 0.299 | 0.195 | 0.540 | 0.424 | 0.493 | 0.341 | 0.498 | 0.324 |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.538 | 0.308 | 0.516 | 0.207 | 0.528 | 0.340 | 0.493 | 0.179 | 0.282 | 0.201 | 0.471 | 0.327 | 0.439 | 0.305 | 0.441 | 0.273 |

| ALOPE-TL(-24) | ||||||||||||||||

| Llama-2-7B | 0.526 | 0.356 | 0.544 | 0.293 | 0.610 | 0.375 | 0.486 | 0.259 | 0.241 | 0.164 | 0.618 | 0.445 | 0.526 | 0.357 | 0.513 | 0.331 |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.458 | 0.294 | 0.507 | 0.261 | 0.575 | 0.388 | 0.456 | 0.223 | 0.284 | 0.198 | 0.456 | 0.362 | 0.513 | 0.374 | 0.477 | 0.324 |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.516 | 0.311 | 0.449 | 0.257 | 0.548 | 0.355 | 0.448 | 0.251 | 0.270 | 0.205 | 0.549 | 0.392 | 0.510 | 0.371 | 0.523 | 0.343 |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.433 | 0.262 | 0.484 | 0.220 | 0.528 | 0.300 | 0.506 | 0.235 | 0.221 | 0.153 | 0.409 | 0.264 | 0.408 | 0.281 | 0.418 | 0.237 |

Appendix D. Spearman Correlation Scores of Decoder-Based Methods Across Selected Models

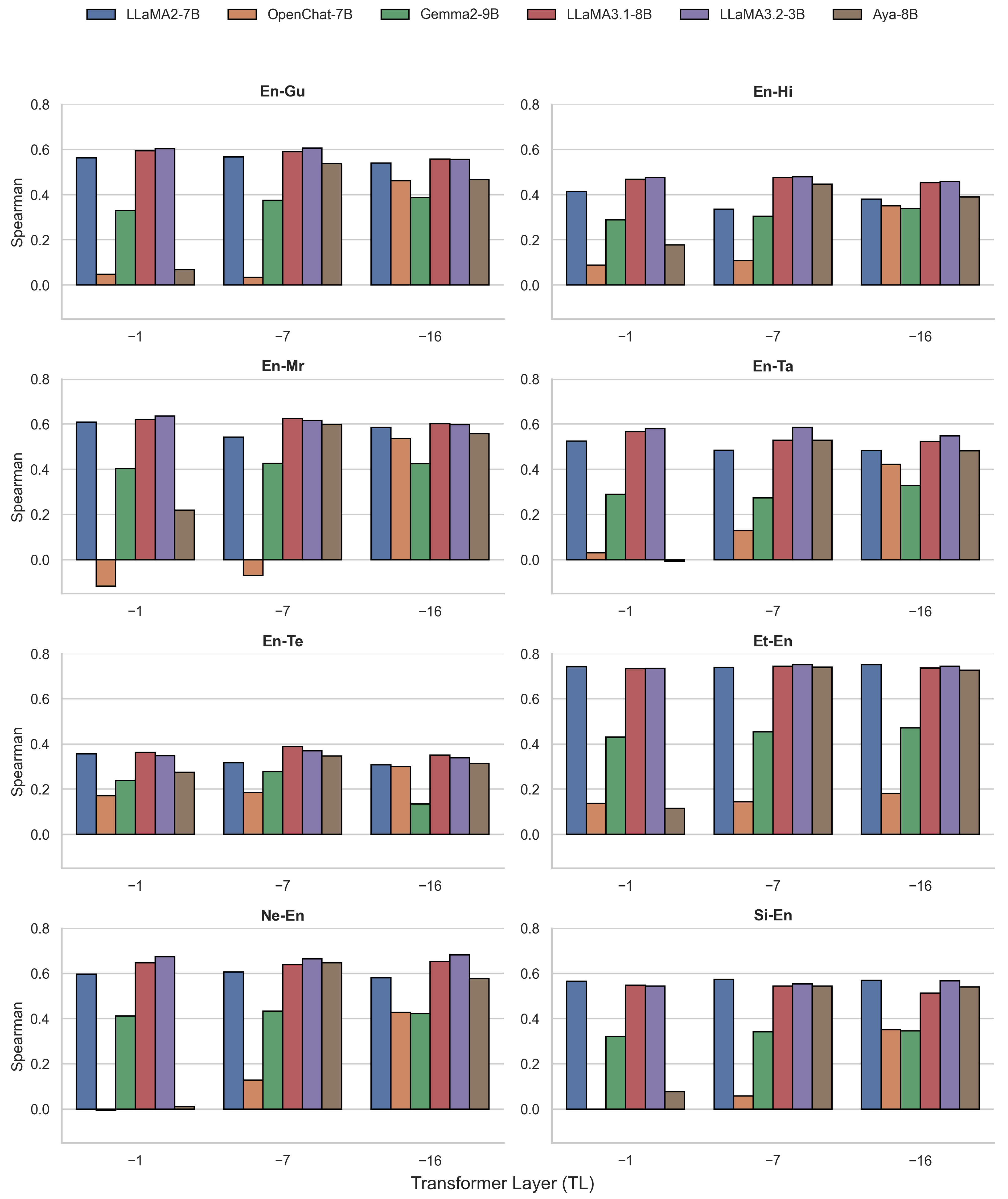

Appendix E. Spearman Correlation Scores Across Selected Transformer Layers (TL) with ALOPE Fine-Tuning

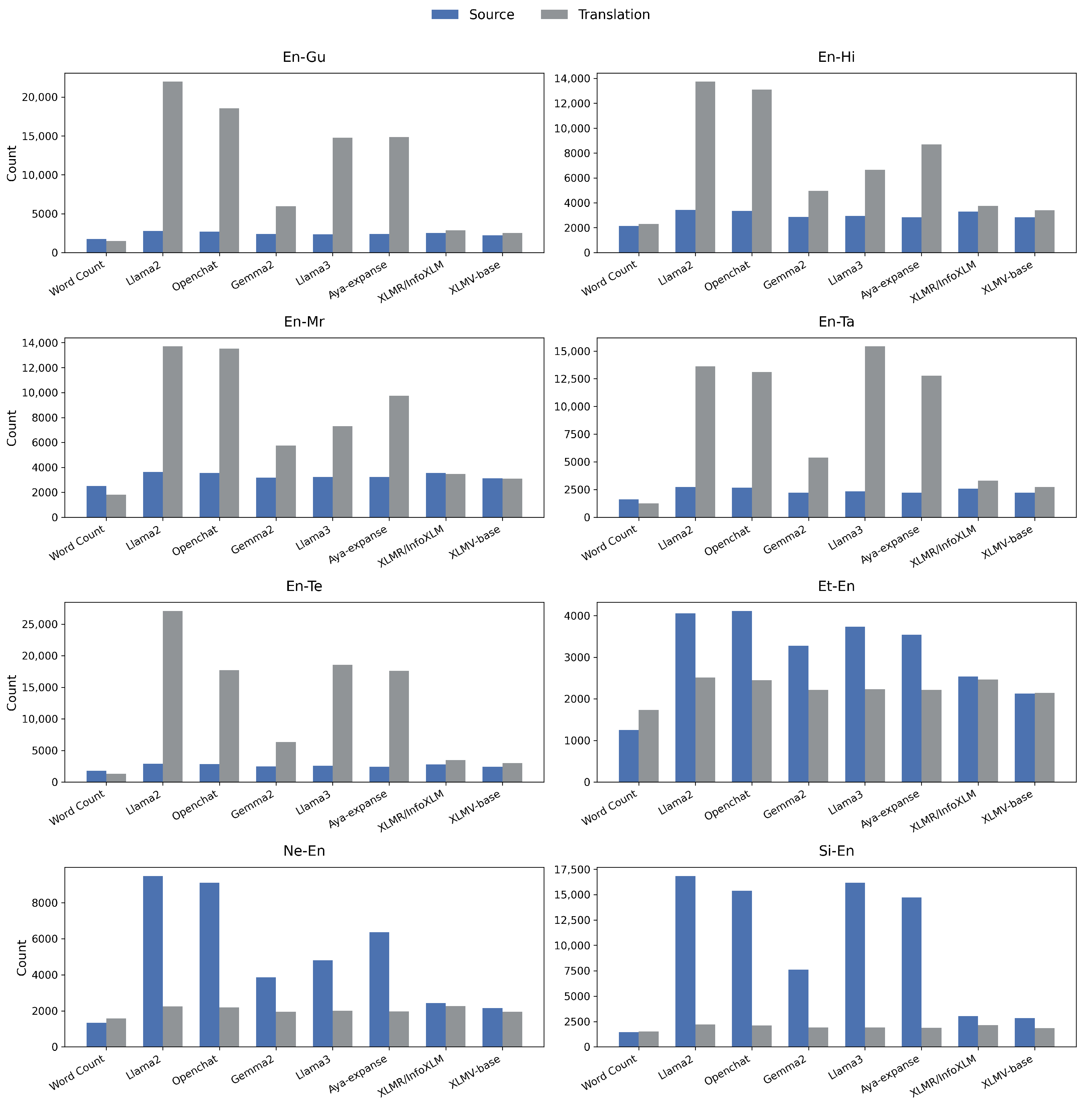

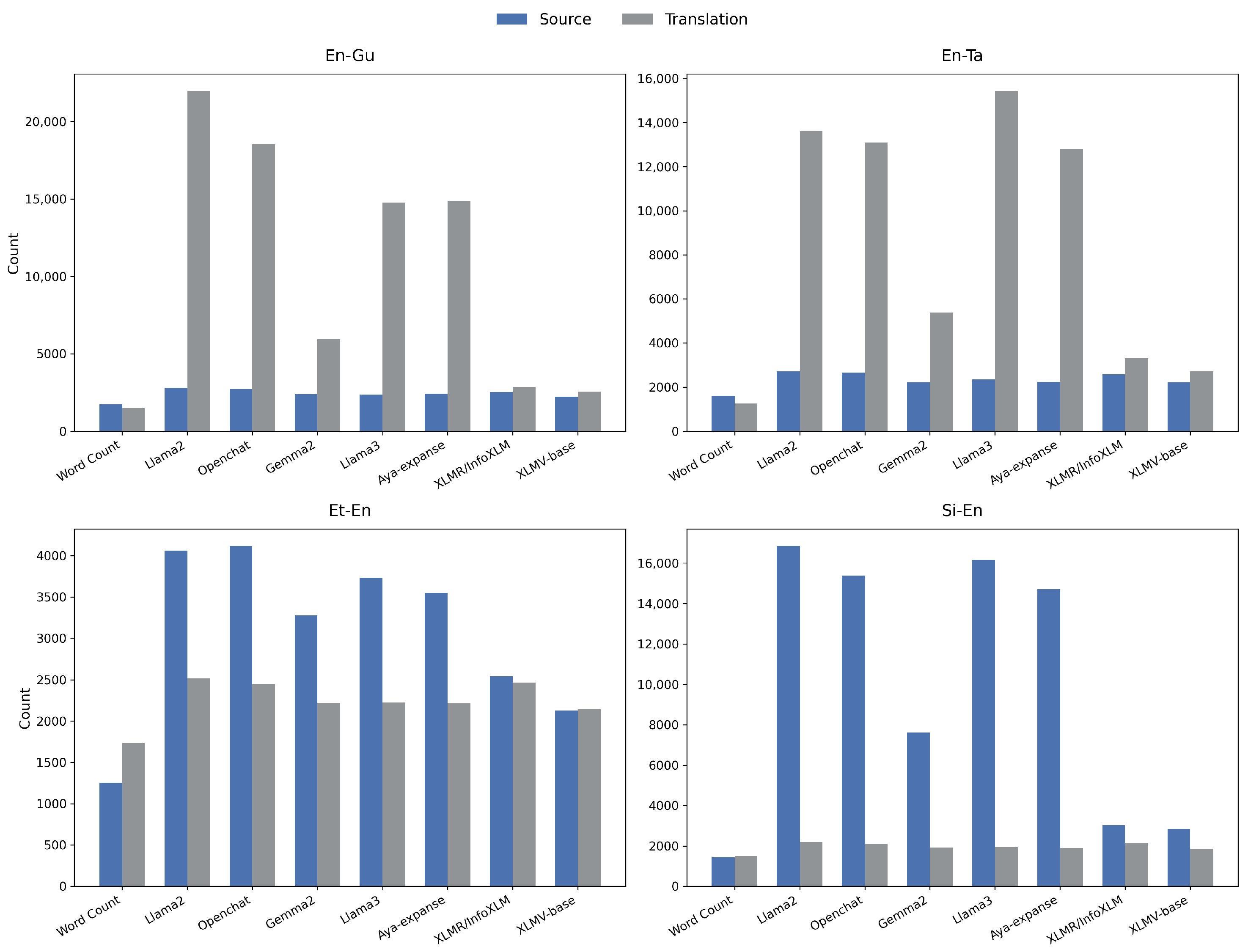

Appendix F. Tokenization Analysis with All the Language Pairs

References

- Kumar, A.; Kunchukuttan, A.; Puduppully, R.; Dabre, R. In-context Example Selection for Machine Translation Using Multiple Features. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.14105. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-jussà, M.R.; Cross, J.; Çelebi, O.; Elbayad, M.; Heafield, K.; Heffernan, K.; Kalbassi, E.; Lam, J.; Licht, D.; Maillard, J.; et al. No language left behind: Scaling human-centered machine translation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.04672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocmi, T.; Bawden, R.; Bojar, O.; Dvorkovich, A.; Federmann, C.; Fishel, M.; Gowda, T.; Graham, Y.; Grundkiewicz, R.; Haddow, B.; et al. Findings of the 2022 conference on machine translation (WMT22). In Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Machine Translation (WMT), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–8 December 2022; pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pitman, J. Google Translate: One Billion Installs, One Billion Stories—Blog.Google. 2021. Available online: https://blog.google/products/translate/one-billion-installs/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Almahasees, Z.; Meqdadi, S.; Albudairi, Y. Evaluation of Google Translate in Rendering English COVID-19 Texts into Arabic. J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 2021, 17, 2065–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranathunga, S.; Lee, E.S.A.; Prifti Skenduli, M.; Shekhar, R.; Alam, M.; Kaur, R. Neural Machine Translation for Low-Resource Languages: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papineni, K.; Roukos, S.; Ward, T.; Zhu, W.J. Bleu: A Method for Automatic Evaluation of Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 7 –12 July 2002; Isabelle, P., Charniak, E., Lin, D., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2002; pp. 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Y.; Baldwin, T.; Moffat, A.; Zobel, J. Continuous Measurement Scales in Human Evaluation of Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 7th Linguistic Annotation Workshop and Interoperability with Discourse, Sofia, Bulgaria, 8–9 August 2013; Pareja-Lora, A., Liakata, M., Dipper, S., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lommel, A.R.; Burchardt, A.; Uszkoreit, H. Multidimensional quality metrics: A flexible system for assessing translation quality. In Proceedings of the Translating and the Computer 35, London, UK, 28–29 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Specia, L.; Paetzold, G.; Scarton, C. Multi-level translation quality prediction with quest++. In Proceedings of the ACL-IJCNLP 2015 System Demonstrations, Beijing, China, 26–31 July 2015; pp. 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Scarton, C.; Specia, L. Document-level translation quality estimation: Exploring discourse and pseudo-references. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 16–18 June 2014; pp. 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kepler, F.; Trénous, J.; Treviso, M.; Vera, M.; Martins, A.F. OpenKiwi: An open source framework for quality estimation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.08646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepler, F.; Trénous, J.; Treviso, M.; Vera, M.; Góis, A.; Farajian, M.A.; Lopes, A.V.; Martins, A.F.T. Unbabel’s Participation in the WMT19 Translation Quality Estimation Shared Task. In Proceedings of the Fourth Conference on Machine Translation, Florence, Italy, 1–2 August 2019; Volume 3: Shared Task Papers, Day 2, pp. 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specia, L.; Blain, F.; Logacheva, V.; Astudillo, R.F.; Martins, A.F.T. Findings of the WMT 2018 Shared Task on Quality Estimation. In Proceedings of the Third Conference on Machine Translation: Shared Task Papers, Belgium, Brussels, 31 October–1 November 2018; pp. 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rei, R.; Treviso, M.; Guerreiro, N.M.; Zerva, C.; Farinha, A.C.; Maroti, C.; de Souza, J.G.C.; Glushkova, T.; Alves, D.; Lavie, A.; et al. CometKiwi: IST-Unbabel 2022 Submission for the Quality Estimation Shared Task. In Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Machine Translation (WMT), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–8 December 2022; Koehn, P., Barrault, L., Bojar, O., Bougares, F., Chatterjee, R., Costa-jussà, M.R., Federmann, C., Fishel, M., Fraser, A., Freitag, M., et al., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 634–645. [Google Scholar]

- Ranasinghe, T.; Orasan, C.; Mitkov, R. TransQuest: Translation Quality Estimation with Cross-lingual Transformers. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Barcelona, Spain, 13–18 September 2020; Scott, D., Bel, N., Zong, C., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 5070–5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrella, S.; Proietti, L.; Scirè, A.; Campolungo, N.; Navigli, R. MATESE: Machine Translation Evaluation as a Sequence Tagging Problem. In Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Machine Translation (WMT), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–8 December 2022; pp. 569–577. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, J.; Vera, M.; van Stigt, D.; Kepler, F.; Martins, A.F. Ist-unbabel participation in the wmt20 quality estimation shared task. In Proceedings of the Fifth Conference on Machine Translation, Virtual, 19–20 November 2020; pp. 1029–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, Y.; Kim, Z.M.; Moon, J.; Kim, H.; Park, E. PATQUEST: Papago Translation Quality Estimation. In Proceedings of the Fifth Conference on Machine Translation, Virtual, 19–20 November 2020; pp. 991–998. [Google Scholar]

- Conneau, A.; Khandelwal, K.; Goyal, N.; Chaudhary, V.; Wenzek, G.; Guzmán, F.; Grave, E.; Ott, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Unsupervised Cross-lingual Representation Learning at Scale. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Virtual, 5–10 July 2020; Jurafsky, D., Chai, J., Schluter, N., Tetreault, J., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 8440–8451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gu, J.; Goyal, N.; Li, X.; Edunov, S.; Ghazvininejad, M.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L. Multilingual denoising pre-training for neural machine translation. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2020, 8, 726–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Burstein, J., Doran, C., Solorio, T., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2019; Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocmi, T.; Federmann, C. Large Language Models Are State-of-the-Art Evaluators of Translation Quality. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference of the European Association for Machine Translation, Tampere, Finland, 12–15 June 2023; Nurminen, M., Brenner, J., Koponen, M., Latomaa, S., Mikhailov, M., Schierl, F., Ranasinghe, T., Vanmassenhove, E., Vidal, S.A., Aranberri, N., et al., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Mujadia, V.; Mishra, P.; Ahsan, A.M.; Sharma, D. Towards Large Language Model driven Reference-less Translation Evaluation for English and Indian Language. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Natural Language Processing (ICON), Goa, India, 14–17 December 2023; Pawar, J.D., Lalitha Devi, S., Eds.; Goa University: Goa, India, 2023; pp. 357–369. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhujan, A.; Kanojia, D.; Orasan, C.; Qian, S. When LLMs Struggle: Reference-less Translation Evaluation for Low-resource Languages. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Language Models for Low-Resource Languages, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 19–20 January 2025; Hettiarachchi, H., Ranasinghe, T., Rayson, P., Mitkov, R., Gaber, M., Premasiri, D., Tan, F.A., Uyangodage, L., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 437–459. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.; Park, J. Papago’s Submission to the WMT22 Quality Estimation Shared Task. In Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Machine Translation (WMT), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–8 December 2022; pp. 627–633. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, K.; Wan, Y.; Liu, D.; Yang, B.; Lei, W.; He, X.; Wong, D.F.; Xie, J. Alibaba-Translate China’s Submission for WMT 2022 Quality Estimation Shared Task. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.10049. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, S.; Tao, S.; Yang, H.; Chen, J. NJUNLP’s Participation for the WMT2022 Quality Estimation Shared Task. In Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Machine Translation (WMT), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–8 December 2022; pp. 615–620. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhujan, A.; Kanojia, D.; Orăsan, C. Optimizing quality estimation for low-resource language translations: Exploring the role of language relatedness. In Proceedings of the International Conference on New Trends in Translation and Technology Conference 2024, Varna, Bulgaria, Spain, 3–6 July 2024; Incoma Ltd.: Sevilla, Spain, 2024; pp. 170–190. [Google Scholar]

- Deoghare, S.; Choudhary, P.; Kanojia, D.; Ranasinghe, T.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Orăsan, C. A Multi-task Learning Framework for Quality Estimation. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023, Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; pp. 9191–9205. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A Survey of Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2303.18223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guzmán, F.; Chen, P.J.; Ott, M.; Pino, J.; Lample, G.; Koehn, P.; Chaudhary, V.; Ranzato, M. The flores evaluation datasets for low-resource machine translation: Nepali-english and sinhala-english. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.01382. [Google Scholar]

- Blain, F.; Zerva, C.; Rei, R.; Guerreiro, N.M.; Kanojia, D.; de Souza, J.G.C.; Silva, B.; Vaz, T.; Jingxuan, Y.; Azadi, F.; et al. Findings of the WMT 2023 Shared Task on Quality Estimation. In Proceedings of the Eighth Conference on Machine Translation, Singapore, 6–7 December 2023; Koehn, P., Haddow, B., Kocmi, T., Monz, C., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 629–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerva, C.; Blain, F.; Rei, R.; Lertvittayakumjorn, P.; de Souza, J.G.C.; Eger, S.; Kanojia, D.; Alves, D.; Orăsan, C.; Fomicheva, M.; et al. Findings of the WMT 2022 Shared Task on Quality Estimation. In Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Machine Translation (WMT), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–8 December 2022; Koehn, P., Barrault, L., Bojar, O., Bougares, F., Chatterjee, R., Costa-Jussà, M.R., Federmann, C., Fishel, M., Fraser, A., Freitag, M., et al., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Specia, L.; Blain, F.; Fomicheva, M.; Fonseca, E.; Chaudhary, V.; Guzmán, F.; Martins, A.F.T. Findings of the WMT 2020 Shared Task on Quality Estimation. In Proceedings of the Fifth Conference on Machine Translation, Virtual, 19–20 November 2020; Barrault, L., Bojar, O., Bougares, F., Chatterjee, R., Costa-Jussà, M.R., Federmann, C., Fishel, M., Fraser, A., Graham, Y., Guzman, P., et al., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 743–764. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhujan, A.; Kanojia, D.; Orasan, C.; Ranasinghe, T. SurreyAI 2023 Submission for the Quality Estimation Shared Task. In Proceedings of the Eighth Conference on Machine Translation, Singapore, 6–7 December 2023; Koehn, P., Haddow, B., Kocmi, T., Monz, C., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzek, G.; Lachaux, M.A.; Conneau, A.; Chaudhary, V.; Guzmán, F.; Joulin, A.; Grave, E. CCNet: Extracting High Quality Monolingual Datasets from Web Crawl Data. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Marseille, France, 11–16 May 2020; Calzolari, N., Béchet, F., Blache, P., Choukri, K., Cieri, C., Declerck, T., Goggi, S., Isahara, H., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., et al., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 4003–4012. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.; Gonen, H.; Mao, Y.; Hou, R.; Goyal, N.; Ghazvininejad, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Khabsa, M. XLM-V: Overcoming the Vocabulary Bottleneck in Multilingual Masked Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; Bouamor, H., Pino, J., Bali, K., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 13142–13152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Z.; Dong, L.; Wei, F.; Yang, N.; Singhal, S.; Wang, W.; Song, X.; Mao, X.L.; Huang, H.; Zhou, M. InfoXLM: An Information-Theoretic Framework for Cross-Lingual Language Model Pre-Training. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Virtual, 6–11 June 2021; Toutanova, K., Rumshisky, A., Zettlemoyer, L., Hakkani-Tur, D., Beltagy, I., Bethard, S., Cotterell, R., Chakraborty, T., Zhou, Y., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 3576–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rei, R.; Guerreiro, N.M.; Pombal, J.; van Stigt, D.; Treviso, M.; Coheur, L.; de Souza, J.G.C.; Martins, A. Scaling up CometKiwi: Unbabel-IST 2023 Submission for the Quality Estimation Shared Task. In Proceedings of the Eighth Conference on Machine Translation, Singapore, 6–7 December 2023; Koehn, P., Haddow, B., Kocmi, T., Monz, C., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.F.T.; Astudillo, R.F. From Softmax to Sparsemax: A Sparse Model of Attention and Multi-Label Classification. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.02068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, N.M.; Rei, R.; Stigt, D.V.; Coheur, L.; Colombo, P.; Martins, A.F.T. xcomet: Transparent Machine Translation Evaluation through Fine-grained Error Detection. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2024, 12, 979–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomicheva, M.; Sun, S.; Fonseca, E.; Zerva, C.; Blain, F.; Chaudhary, V.; Guzmán, F.; Lopatina, N.; Specia, L.; Martins, A.F.T. MLQE-PE: A Multilingual Quality Estimation and Post-Editing Dataset. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Marseille, France, 20–25 June 2022; Calzolari, N., Béchet, F., Blache, P., Choukri, K., Cieri, C., Declerck, T., Goggi, S., Isahara, H., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., et al., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 4963–4974. [Google Scholar]

- Sai B, A.; Dixit, T.; Nagarajan, V.; Kunchukuttan, A.; Kumar, P.; Khapra, M.M.; Dabre, R. IndicMT Eval: A Dataset to Meta-Evaluate Machine Translation Metrics for Indian Languages. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; Rogers, A., Boyd-Graber, J., Okazaki, N., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; Volume 1: Long Papers, pp. 14210–14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinska, M.; Raj, N.; Thai, K.; Song, Y.; Gupta, A.; Iyyer, M. DEMETR: Diagnosing Evaluation Metrics for Translation. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 7–11 December 2022; Goldberg, Y., Kozareva, Z., Zhang, Y., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 9540–9561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rei, R.; Guerreiro, N.M.; Pombal, J.; Alves, J.; Teixeirinha, P.; Farajian, A.; Martins, A.F.T. Tower+: Bridging Generality and Translation Specialization in Multilingual LLMs. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.17080. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhujan, A.; Qian, S.; Matthew, C.C.C.; Orasan, C.; Kanojia, D. ALOPE: Adaptive Layer Optimization for Translation Quality Estimation using Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.07484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.M.; Santurkar, S.; Ma, T.; Liang, P. Data Selection for Language Models via Importance Resampling. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.03169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedemann, J. Parallel Data, Tools and Interfaces in OPUS. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’12), Istanbul, Turkey, 23–25 May 2012; Calzolari, N., Choukri, K., Declerck, T., Doğan, M.U., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., Moreno, A., Odijk, J., Piperidis, S., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 2214–2218. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Vargus, F.; D’souza, D.; Karlsson, B.F.; Mahendiran, A.; Ko, W.Y.; Shandilya, H.; Patel, J.; Mataciunas, D.; O’Mahony, L.; et al. Aya Dataset: An Open-Access Collection for Multilingual Instruction Tuning. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; Ku, L.W., Martins, A., Srikumar, V., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2024; Volume 1: Long Papers, pp. 11521–11567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, N.; Morrison, J.; Pyatkin, V.; Huang, S.; Ivison, H.; Brahman, F.; Miranda, L.J.V.; Liu, A.; Dziri, N.; Lyu, S.; et al. Tulu 3: Pushing Frontiers in Open Language Model Post-Training. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2411.15124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Agrawal, R.; Zhang, S.; Indurthi, S.R.; Zhao, S.; Song, K.; Xu, S.; Zhu, C. WPO: Enhancing RLHF with Weighted Preference Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; Al-Onaizan, Y., Bansal, M., Chen, Y.N., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 8328–8340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.09685. [Google Scholar]

- Kocmi, T.; Federmann, C. GEMBA-MQM: Detecting Translation Quality Error Spans with GPT-4. In Proceedings of the Eighth Conference on Machine Translation, Singapore, 6–7 December 2023; Koehn, P., Haddow, B., Kocmi, T., Monz, C., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. BMJ 2014, 349, g7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, I.; Huang, Y.; Chen, J.; Benesty, J.; Benesty, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Cohen, I. Pearson correlation coefficient. In Noise Reduction in Speech Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lapata, M. Automatic Evaluation of Information Ordering: Kendall’s Tau. Comput. Linguist. 2006, 32, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chok, N.S. Pearson’s Versus Spearman’s and Kendall’s Correlation Coefficients for Continuous Data. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rei, R.; Stewart, C.; Farinha, A.C.; Lavie, A. COMET: A neural framework for MT evaluation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.09025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, A.B.; Nagarajan, V.; Dixit, T.; Dabre, R.; Kunchukuttan, A.; Kumar, P.; Khapra, M.M. IndicMT Eval: A Dataset to Meta-Evaluate Machine Translation metrics for Indian Languages. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.10180. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Y.; Baldwin, T. Testing for Significance of Increased Correlation with Human Judgment. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; Moschitti, A., Pang, B., Daelemans, W., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E. Regression Analysis; Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics: Applied Probability and Statist Ics Section Series; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, X.P.; Aljunied, M.; Joty, S.; Bing, L. Democratizing LLMs for Low-Resource Languages by Leveraging their English Dominant Abilities with Linguistically-Diverse Prompts. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; Ku, L.W., Martins, A., Srikumar, V., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 3501–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Split | En-Gu | En-Hi | En-Mr | En-Ta | En-Te | Et-En | Ne-En | Si-En |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | 7000 | 7000 | 26,000 | 7000 | 7000 | 7000 | 7000 | 7000 |

| Testing | 1000 | 1000 | 699 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Method | En-Gu | En-Hi | En-Mr | En-Ta | En-Te | Et-En | Ne-En | Si-En |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MonoTQ-InfoXLM-Large | 0.630 | 0.478 | 0.606 | 0.603 | 0.358 | 0.760 | 0.718 | 0.579 |

| MonoTQ-XLM-V | 0.552 | 0.446 | 0.556 | 0.607 | 0.358 | 0.766 | 0.705 | 0.595 |

| MonoTQ-XLM-R-Large | 0.599 | 0.491 | 0.457 | 0.627 | 0.339 | 0.737 | 0.700 | 0.575 |

| CometKiwi-22 (InfoXLM) | 0.574 | 0.408 | 0.627 | 0.567 | 0.231 | 0.827 | 0.755 | 0.648 |

| CometKiwi-23 (XLM-R-XL) | 0.637 | 0.546 | 0.635 | 0.616 | 0.338 | 0.860 | 0.789 | 0.703 |

| xCOMET-XL | 0.490 | 0.346 | 0.448 | 0.503 | 0.253 | 0.810 | 0.646 | 0.576 |

| Approach | Model | En-Gu | En-Hi | En-Mr | En-Ta | En-Te | Et-En | Ne-En | Si-En |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-shot | Llama-2-7B | 0.006 | −0.002 | 0.053 | 0.067 | −0.016 | 0.168 | 0.153 | 0.144 |

| OpenChat-7B | 0.249 | 0.254 | 0.183 | 0.358 | 0.145 | 0.571 | 0.448 | 0.417 | |

| Gemma-2-9B | * 0.321 | * 0.373 | 0.404 | * 0.468 | * 0.177 | 0.695 | 0.560 | * 0.456 | |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.164 | 0.194 | 0.245 | 0.220 | 0.132 | 0.503 | 0.262 | 0.267 | |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.095 | 0.095 | 0.116 | 0.128 | 0.098 | 0.359 | 0.216 | 0.120 | |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.123 | 0.135 | 0.089 | 0.117 | 0.049 | 0.315 | 0.352 | 0.330 | |

| Tower+-72B | 0.238 | 0.369 | * 0.422 | 0.254 | 0.142 | * 0.753 | * 0.580 | 0.384 | |

| Instruction Fine-Tuned | Llama-2-7B | 0.454 | 0.319 | 0.466 | 0.449 | 0.266 | 0.591 | 0.478 | 0.374 |

| OpenChat-7B | 0.513 | 0.423 | † 0.587 | 0.528 | † 0.302 | 0.692 | 0.599 | 0.477 | |

| Gemma-2-9B | † 0.580 | † 0.471 | 0.533 | † 0.631 | 0.272 | 0.696 | † 0.672 | 0.468 | |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.555 | 0.368 | 0.530 | 0.586 | 0.233 | † 0.728 | 0.618 | † 0.558 | |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.501 | 0.393 | 0.524 | 0.567 | 0.224 | 0.678 | 0.587 | 0.451 | |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.528 | 0.388 | 0.515 | 0.496 | 0.290 | 0.605 | 0.568 | 0.384 | |

| ALOPE-Best (Ours) | Llama-2-7B | 0.567 | 0.414 | 0.609 | 0.525 | 0.356 | 0.751 | 0.606 | 0.573 |

| OpenChat-7B | 0.461 | 0.350 | 0.536 | 0.422 | 0.301 | 0.180 | 0.427 | 0.352 | |

| Gemma-2-9B | 0.387 | 0.339 | 0.426 | 0.328 | 0.278 | 0.471 | 0.433 | 0.346 | |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.594 | 0.477 | 0.625 | 0.567 | 0.388 | 0.744 | 0.652 | 0.547 | |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.606 | 0.479 | 0.636 | 0.610 | 0.373 | 0.751 | 0.682 | 0.567 | |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.538 | 0.447 | 0.597 | 0.528 | 0.347 | 0.741 | 0.646 | 0.544 |

| TL | Model | En-Gu | En-Hi | En-Mr | En-Ta | En-Te | Et-En | Ne-En | Si-En |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TL (-1) | Llama-2-7B | 0.563 | 0.414 | 0.609 | 0.525 | 0.356 | 0.742 | 0.596 | 0.565 |

| OpenChat-7B | 0.048 | 0.088 | −0.117 | 0.030 | 0.171 | 0.137 | −0.005 | −0.001 | |

| Gemma-2-9B | 0.331 | 0.288 | 0.403 | 0.289 | 0.238 | 0.431 | 0.411 | 0.322 | |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.594 | 0.469 | 0.620 | 0.567 | 0.363 | 0.734 | 0.647 | 0.547 | |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.604 | 0.477 | 0.636 | 0.580 | 0.348 | 0.735 | 0.674 | 0.543 | |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.068 | 0.178 | 0.219 | −0.006 | 0.275 | 0.115 | 0.012 | 0.077 | |

| TL (-7) | Llama-2-7B | 0.567 | 0.336 | 0.542 | 0.484 | 0.317 | 0.739 | 0.606 | 0.573 |

| OpenChat-7B | 0.034 | 0.108 | −0.069 | 0.129 | 0.185 | 0.144 | 0.128 | 0.057 | |

| Gemma-2-9B | 0.375 | 0.304 | 0.426 | 0.273 | 0.278 | 0.454 | 0.433 | 0.342 | |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.590 | 0.477 | 0.625 | 0.528 | 0.388 | 0.744 | 0.638 | 0.544 | |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.606 | 0.479 | 0.617 | 0.585 | 0.369 | 0.751 | 0.664 | 0.553 | |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.538 | 0.447 | 0.597 | 0.528 | 0.347 | 0.741 | 0.646 | 0.544 | |

| TL (-16) | Llama-2-7B | 0.540 | 0.381 | 0.585 | 0.482 | 0.308 | 0.751 | 0.580 | 0.569 |

| OpenChat-7B | 0.461 | 0.350 | 0.536 | 0.422 | 0.301 | 0.180 | 0.427 | 0.352 | |

| Gemma-2-9B | 0.387 | 0.339 | 0.425 | 0.328 | 0.134 | 0.471 | 0.422 | 0.346 | |

| Llama-3.1-8B | 0.558 | 0.453 | 0.602 | 0.523 | 0.350 | 0.737 | 0.652 | 0.513 | |

| Llama-3.2-3B | 0.557 | 0.459 | 0.597 | 0.547 | 0.338 | 0.745 | 0.682 | 0.567 | |

| Aya-Expanse-8B | 0.467 | 0.390 | 0.557 | 0.481 | 0.314 | 0.727 | 0.576 | 0.540 |

| Language Pair | Multi-Layer Regression | Dynamic Weighting | IFT | Best of Layer Specific ALOPE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 to −7 | −8 to −11 | −12 to −16 | −1 to −7 | −8 to −11 | −12 to −16 | |||

| En–Gu | 0.569 | 0.528 | 0.565 | 0.532 | 0.565 | 0.563 | 0.501 | 0.606 |

| En–Hi | 0.458 | 0.440 | 0.416 | 0.465 | 0.382 | 0.462 | 0.393 | 0.479 |

| En–Mr | 0.597 | 0.596 | 0.566 | 0.603 | 0.587 | 0.599 | 0.524 | 0.636 |

| En–Ta | 0.496 | 0.524 | 0.534 | 0.532 | 0.525 | 0.492 | 0.567 | 0.610 |

| En–Te | 0.351 | 0.303 | 0.347 | 0.339 | 0.325 | 0.355 | 0.224 | 0.373 |

| Et–En | 0.654 | 0.668 | 0.682 | 0.679 | 0.681 | 0.673 | 0.678 | 0.751 |

| Ne–En | 0.550 | 0.597 | 0.575 | 0.566 | 0.579 | 0.606 | 0.587 | 0.682 |

| Si–En | 0.504 | 0.475 | 0.523 | 0.493 | 0.468 | 0.482 | 0.451 | 0.567 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sindhujan, A.; Kanojia, D.; Orăsan, C. Reference-Less Evaluation of Machine Translation: Navigating Through the Resource-Scarce Scenarios. Information 2025, 16, 916. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16100916

Sindhujan A, Kanojia D, Orăsan C. Reference-Less Evaluation of Machine Translation: Navigating Through the Resource-Scarce Scenarios. Information. 2025; 16(10):916. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16100916

Chicago/Turabian StyleSindhujan, Archchana, Diptesh Kanojia, and Constantin Orăsan. 2025. "Reference-Less Evaluation of Machine Translation: Navigating Through the Resource-Scarce Scenarios" Information 16, no. 10: 916. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16100916

APA StyleSindhujan, A., Kanojia, D., & Orăsan, C. (2025). Reference-Less Evaluation of Machine Translation: Navigating Through the Resource-Scarce Scenarios. Information, 16(10), 916. https://doi.org/10.3390/info16100916