Extracting Narrative Patterns in Different Textual Genres: A Multilevel Feature Discourse Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (RQ1) Which linguistic features seem to be generally linked to each textual genre, and how prevalent are they?

- (RQ2) Is it possible to establish a connection between particular linguistic features and certain genres, given their main communicative purposes?

2. Related Work

3. Data and Tools

3.1. Corpora Collection

3.2. Linguistic Processing

- Freeling [45], a popular multilingual tool that allows us to obtain lexical, syntactic, and semantic information from a document. For example, features such as the presence of types of phrases, specific grammatical elements, or named entities were obtained thanks to this tool.

- AllenNLP [46]. This tool was used for the particular task of coreference resolution, as AllenNLP currently represents most of the state of the art on this specific research topic. Indeed, Freeling also includes a coreference resolution module, but it was observed that AllenNLP gave more adequate and complete results for the purpose of the present study. The coreference resolution model used is a model based on [47].

- CAEVO (Cascading Event Ordering system) [48], a tool capable of extracting and classifying discursive information related to events, time, and temporal expressions. For this purpose, it takes into account the TimeML specification [49], according to which an event refers to something that occurs or happens, and can be articulated by different kinds of expressions such as verbs, nominalizations, or adjectives. In addition, the tool classifies events semantically into one of seven categories: aspectual, perception, state, reporting, intensional action, intensional state, and occurrence. With this tool it is possible to extract all the interesting information regarding the event phenomena, not only with the terms that the tool identifies as events, but also their semantic environment.

4. Multilevel Feature Study of the Genres

4.1. Shallow Features

4.1.1. Word Length

4.1.2. Commas

4.2. Part-of-Speech (POS) and Syntactic Features

4.2.1. Nouns and Proper Nouns

4.2.2. Personal Pronouns

4.2.3. Adjectives and Adverbs/Wh-Adverbs

4.2.4. Verbal Tenses

4.2.5. Nonfinite Verb Forms

4.2.6. Predicative Complement

4.2.7. Figures

4.3. Semantic Features

4.3.1. Events

4.3.2. Time Links

4.3.3. Named Entity Length

4.3.4. Parenthesis, Interrogative, and Exclamatory Sentences

4.3.5. Subject and Object Dependency Relations

4.4. Discourse-Related Features

4.4.1. Coreference

4.4.2. Discourse Markers

4.4.3. Time Expressions

4.4.4. Quotation Marks

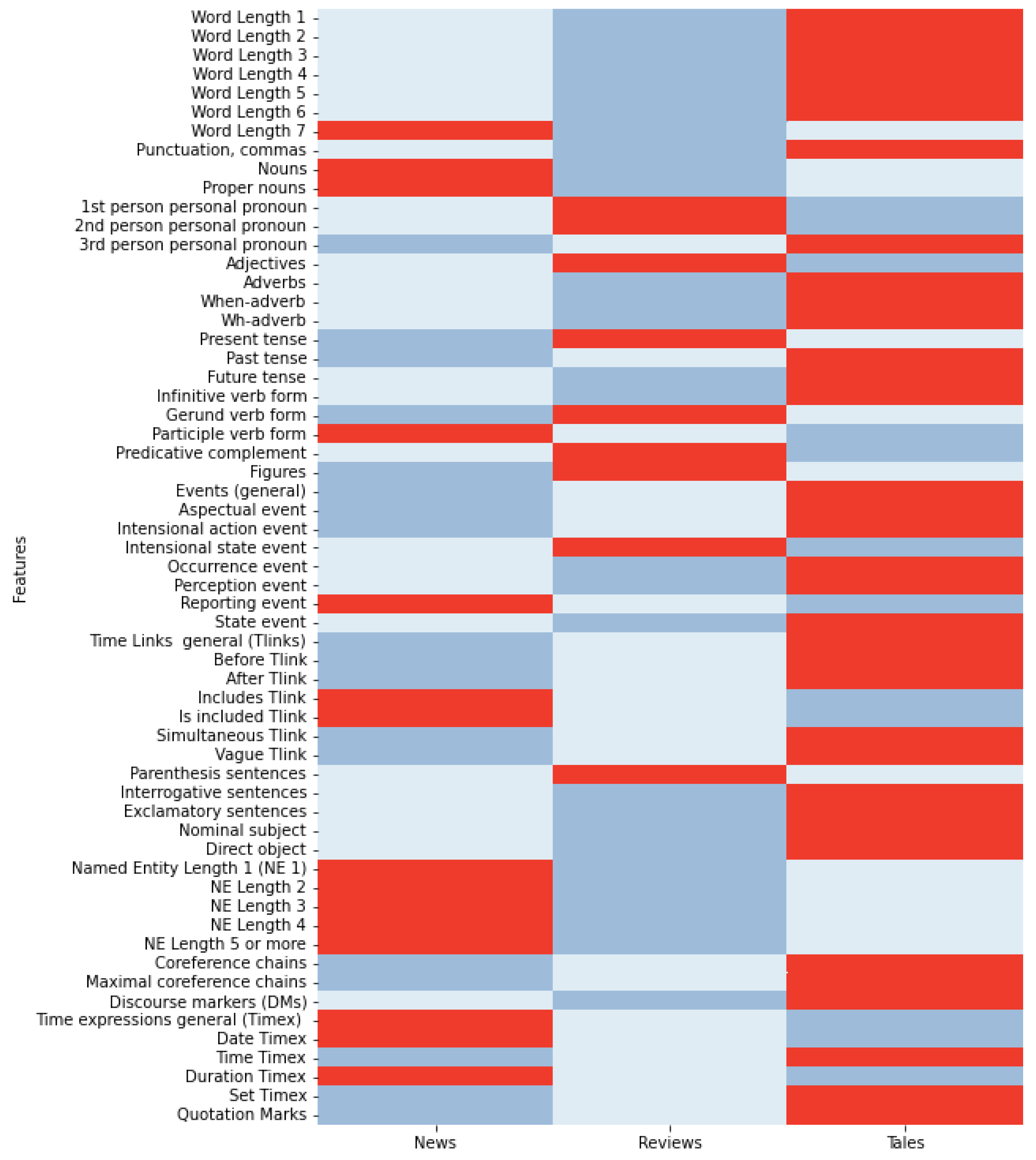

5. Overall and Final Remarks

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bögel, T.; Strötgen, J.; Gertz, M. Computational narratology: Extracting tense clusters from narrative texts. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation 2014, Reykjavik, Iceland, 26–31 May 2014; European Language Resources Association: Paris, France, 2014; Volume 14, pp. 950–955. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, I. Computational narratology. In Handbook of Narratology; Hühn, P., Meister, J.C., Pier, J., Schmid, W., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin/München, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.S. Discourse modes: Aspectual entities and tense interpretation. Cah. Gramm. 2001, 26, 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, W.; Waletzky, J. Narrative analysis. Essays on the verbal and visual arts. In Proceedings of the 1966 Spring Meeting of the American Ethnological Society, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 8–9 April 1966; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Igl, N.; Zeman, S. Perspectives on Narrativity and Narrative Perspectivization; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M.L. Toward a definition of narrative. In The Cambridge Companion to Narrative; Herman, D., Ed.; Cambridge Companions to Literature; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, D. Story Logic: Problems and Possibilities of Narrative; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, D. Basic Elements of Narrative; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Swales, J. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings; Cambridge University Press: Cambirdge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, V.K. Analysing Genre: Language Use in Professional Settings; Applied Linguistics and Language Study; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Askehave, I.; Swales, J.M. Genre identification and communicative purpose: A problem and a possible solution. Appl. Linguist. 2001, 22, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fina, A.; Georgakopoulou, A. The Handbook of Narrative Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Draheim, D.; Pappel, I.; Lauk, M.; Mcbride, K.; Misnikov, Y.; Nagumo, T.; Lemke, F.; Hartleb, F. On the narratives and background narratives of e-government. In Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2020; HICSS: Maui, Hawaii, USA, 2020; pp. 2114–2122. [Google Scholar]

- Luno, J.A.; Louwerse, M.; Beck, J.G. Tell us your story: Investigating the linguistic features of trauma narrative. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, Berlin, Germany, 31 July–3 August 2013; Knauff, M., Pauen, M., Sebanz, N., Wachsmuth, I., Eds.; The Cognitive Science Society: Seattle, WA, USA, 2013; pp. 2955–2960. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, K.R. News from the future: A corpus linguistic analysis of future-oriented, unreal and counterfactual news discourse. Discourse Commun. 2016, 10, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Huang, R. Temporal event knowledge acquisition via identifying narratives. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; Association for Computational Linguistics: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, V.K. Interdiscursivity in professional communication. Discourse Commun. 2010, 4, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzone, G.E. Genre analysis. In The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction; Tracy, K., Sandel, T., Ilie, C., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; McKeown, K. Towards automatic detection of narrative structure. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation 2014, Reykjavik, Iceland, 26–31 May 2014; European Language Resources Association: Paris, France, 2014; pp. 4624–4631. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, R.; Rahimtoroghi, E.; Corcoran, T.; Walker, M. Identifying narrative clause types in personal stories. In Proceedings of the 15th Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 18–20 June 2014; Association for Computational Linguistics: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Propp, V.I. Morphology of the Folktale; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1968; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Gervás, P. Computational drafting of plot structures for Russian folk tales. Cogn. Comput. 2016, 8, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imabuchi, S.; Ogata, T. A story generation system based on Propp theory as a mechanism in an integrated narrative generation system. In Advances in Natural Language Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, D. Variation across Speech and Writing; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, D. The multi-dimensional approach to linguistic analyses of genre variation: An overview of methodology and findings. Comput. Humanit. 1992, 26, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, D.; Conrad, S. Register, Genre, and Style; Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McEnery, T.; Xiao, R.; Tono, Y. Corpus-Based Language Studies: An Advanced Resource Book; Routledge Applied Linguistics; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, I.; Grieve, J. Stylistic variation on the Donald Trump Twitter account: A linguistic analysis of tweets posted between 2009 and 2018. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, S.; Nesi, H.; Biber, D. Discipline, level, genre: Integrating situational perspectives in a new MD analysis of university student writing. Appl. Linguist. 2019, 40, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katinskaya, A.; Sharoff, S. Applying multi-dimensional analysis to a Russian webcorpus: Searching for evidence of genres. In Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Balto-Slavic Natural Language Processing, Hissar, Bulgaria, 10–11 September 2015; Piskorski, J., Pivovarova, L., Šnajder, J., Tanev, H., Yangarber, R., Eds.; INCOMA Ltd.: Shoumen, Bulgaria, 2015; pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, Y.T.; Chen, J.L.; Cha, J.H.; Tseng, H.C.; Chang, T.H.; Chang, K.E. Constructing and validating readability models: The method of integrating multilevel linguistic features with machine learning. Behav. Res. Methods 2015, 47, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Lu, D.; Shen, Y.; Cai, Y. Linguistic feature representation with statistical relational learning for readability assessment. In Proceedings of the 8th CCF International Conference on Natural Language Processing and Chinese Computing, Dunhuang, China, 9–14 October 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimino, A.; Wieling, M.; Dell’Orletta, F.; Montemagni, S.; Venturi, G. Identifying predictive features for textual genre classification: The key role of syntax. In Proceedings of the 4th Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics 2017, Rome, Italy, 11–13 December 2017; Collana dell’Associazione Italiana di Linguistica Computazionale. Accademia University Press: Torino, Italy, 2017; pp. 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zen, E.L. Corpus-driven analysis on the language of children’s literature. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Recent Innovations 2018, Jakarta, Indonesia, 26–28 September 2018; SciTePress—Science and Technology Publications: Setúbal, Portugal, 2018; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almiron-Chamadoira, P. Online reviews as a genre: A semiotic analysis of Amazon.com 2010–2014 reviews on the categories ‘Clothing’ and ‘Electronics’. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Digital Tools & Uses Congress, Paris, France, 3–5 October 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutskiv, A.; Popovych, N. Big data-based approach to automated linguistic analysis effectiveness. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Data Stream Mining & Processing, Lviv, Ukraine, 21–25 August 2020; IEEE: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yae, J.; Yoon, S. The compatibility condition for expressives revisited: A big data-based trend analysis. Lang. Sci. 2017, 64, 69–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamallo, P.; Garcia, M.; Pineiro, C.; Martinez-Castano, R.; Pichel, J.C. LinguaKit: A big data-based multilingual tool for linguistic analysis and information extraction. In Proceedings of the 2018 5th International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security, Valencia, Spain, 15–18 October 2018; IEEE: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacristán, P.P. Bedtime Stories. Short Stories with Values. 2008. Available online: https://freestoriesforkids.com/ (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Lobo, P.V.; De Matos, D.M. Fairy tale corpus organization using latent semantic mapping and an item-to-item top-n recommendation algorithm. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation 2010, Valletta, Malta, 17–23 May 2010; European Language Resources Association: Paris, France, 2010; Volume 10, pp. 1472–1475. [Google Scholar]

- Over, P.; Dang, H.; Harman, D. DUC in context. Inf. Process. Manag. 2007, 43, 1506–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, M.; Anthony, C.; Voll, K.D. Methods for creating semantic orientation dictionaries. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, Genoa, Italy, 22–28 May 2006; European Language Resources Association: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 427–432. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, H.N.T.; Le, A.C.; Nguyen, L.M. Linguistic features for subjectivity classification. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Asian Language Processing, Hanoi, Vietnam, 13–15 November 2012; IEEE Computer Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaimin, M.S.M.; Hijazi, M.H.A.; Alfred, R.; Coenen, F. Natural language processing based features for sarcasm detection: An investigation using bilingual social media texts. In Proceedings of the 2017 8th International Conference on Information Technology, Amman, Jordan, 17–18 May 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padró, L.; Stanilovsky, E. FreeLing 3.0: Towards wider multilinguality. In Proceedings of the 8th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference 2012, Istanbul, Turkey, 21–27 May 2012; ELRA: Paris, France, 2012; pp. 2473–2479. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, M.; Grus, J.; Neumann, M.; Tafjord, O.; Dasigi, P.; Liu, N.; Peters, M.; Schmitz, M.; Zettlemoyer, L. AllenNLP: A deep semantic natural language processing platform. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.07640. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; He, L.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.S. End-to-end neural coreference resolution. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 7–11 September 2017; Association for Computational Linguistics: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, T.; McDowell, B.; Chambers, N.; Bethard, S. An Annotation Framework for Dense Event Ordering; Technical Report; Carnegie-Mellon University: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pustejovsky, J.; Castano, J.M.; Ingria, R.; Sauri, R.; Gaizauskas, R.J.; Setzer, A.; Katz, G.; Radev, D.R. TimeML: Robust specification of event and temporal expressions in text. New Dir. Quest. Answering 2003, 3, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Alemany, L.A. Representing Discourse for Automatic Text Summarization via Shallow NLP Techniques. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gkotsis, G.; Stepanyan, K.; Pedrinaci, C.; Domingue, J.; Liakata, M. It’s all in the content: State of the art best answer prediction based on discretisation of shallow linguistic features. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM Conference on Web Science, Bloomington, IN, USA, 23–26 June 2014; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, A.J.M. Thematic and topical structuring in three subgenres. A contrastive study. Miscelánea J. Engl. Am. Stud. 2003, 27, 131–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dijk, T.A.V. News as Discourse; University of Groningen: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Compagnone, M.R.; Fiorentino, G. TripAdvisor and tourism: The linguistic behaviour of consumers in the tourism industry 2.0. In Strategies of Adaptation in Tourist Communication; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 270–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Bhattacharyya, P. Estimating annotation complexities of text using gaze and textual information. In Cognitively Inspired Natural Language Processing; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 49–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, C. Narrativity and involvement in online consumer reviews: The case of TripAdvisor. Narrat. Inq. 2012, 22, 105–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, J.; Salamó, M.; Martí, M.A. Función de las secuencias narrativas en la clasificación de la polaridad de reviews. Proces. Leng. Nat. 2014, 52, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, J.I.A.; Guijarro, A.J.M. Narración Infantil y Discurso: Estudio Lingüístico de Cuentos en Castellano e Inglés; Number 4 in Colección Arcadia; Universidad de Castilla La Mancha: Cuenca, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C. English newspapers as specimen: A study of linguistic features of the English newspapers in the 20th century from historical linguistics. Stud. Lit. Lang. 2017, 14, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R. English Grammar; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero Salas, F. Elements of English Grammar: Fernando Herrero Salas, 2nd ed.; Bubok Publishing S.L.: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, M.; Maestre, M.M.; Lloret, E.; Cueto, A.S. Leveraging machine learning to explain the nature of written genres. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 24705–24726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurí, R.; Littman, J.; Gaizauskas, R.; Setzer, A.; Pustejovsky, J. TimeML Annotation Guidelines, Version 1.2.1; 2006. Available online: https://timeml.github.io/site/publications/specs.html (accessed on 27 November 2022).

- Sparks, B.; Browning, V. The impact of online reviews on hotel booking intentions and perception of trust. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.S. Modes of Discourse: The Local Structure of Texts; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; Volume 103. [Google Scholar]

- Bertills, Y. Beyond Identification: Proper Names in Children’s Literature; Akademisk Avhandling; Åbo Akademi University Press: Åbo, Finland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Li, Q.; Jin, L.; Feng, L.; Clifton, D.A.; Clifford, G.D. Detecting adolescent psychological pressures from micro-blog. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Health Information Science, Shenzhen, China, 22–23 April 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, A.J.M. The role of semiotic metaphor in the verbal-visual interplay of three children’s picture books. A multisemiotic systemic-functional approach. Atlantis 2016, 38, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Taavitsainen, I. Emphatic language and romantic prose: Changing functions of interjections in a sociocultural perspective. Eur. J. Engl. Stud. 1998, 2, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiola, R. Interjectional issues in translation: A cross-cultural thematized approach. Babel 2016, 62, 300–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitler, E.; Nenkova, A. Revisiting readability: A unified framework for predicting text quality. In Proceedings of the 2008 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–27 October 2008; Association for Computational Linguistics: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2008; pp. 186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.T.; Chen, M.C.; Sun, Y.S. Characterizing the influence of features on reading difficulty estimation for non-native readers. CoRR 2018, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubey, P.K.; Huang, R. Improving event coreference resolution by modeling correlations between event coreference chains and document topic structures. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; Association for Computational Linguistics: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I. How and when do children acquire the use of discourse markers? In Proceedings of the 5th Cambridge Postgraduate Conference in Language Research, Cambridge, UK, 20–21 March 2007; Cambridge Institute of Language Research: Cambridge, UK, 2007; Volume 40, pp. 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Crotts, J.C.; Mason, P.R.; Davis, B. Measuring guest satisfaction and competitive position in the hospitality and tourism industry: An application of stance-shift analysis to travel blog narratives. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabi Sari, I. The analysis of the discourse markers in the narratives elicited from Persian-speaking children. J. Engl. Lang. Pedagog. Pract. 2013, 6, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez, M.V.S. Lenguaje literario, géneros y literatura infantil. In Presente y Futuro de la Literatura Infantil; Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha: Cuenca, Spain, 2000; pp. 27–66. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, I.K.; Burgers, C. Do consumer critics write differently from professional critics? A genre analysis of online film reviews. Discourse Context Media 2013, 2, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # Docs | # Sents | # Words | Sents/Doc | Words/Doc | Words/Sent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| News | 487 | 12,565 | 274,153 | 26 | 563 | 26 |

| Reviews | 447 | 17,150 | 306,120 | 38 | 685 | 21 |

| Tales | 496 | 16,236 | 344,606 | 33 | 695 | 24 |

| Features | News | Reviews | Tales |

|---|---|---|---|

| Word length 1 | 77.37 | 123.79 | 129.11 |

| Word length 2 | 97.55 | 111.09 | 117.98 |

| Word length 3 | 105.07 | 145.62 | 181.90 |

| Word length 4 | 81.50 | 124.25 | 142.56 |

| Word length 5 | 55.36 | 77.01 | 78.78 |

| Word length 6 | 46.85 | 51.27 | 52.52 |

| Word length 7 | 160.72 | 130.85 | 95.94 |

| Punctuation, commas | 32.90 | 33.61 | 58.99 |

| Features | News | Reviews | Tales |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nouns | 168.57 | 164.23 | 139.68 |

| Proper nouns | 46.81 | 33.68 | 22.84 |

| 1st-person pronoun | 3.63 | 17.02 | 10.73 |

| 2nd-person pronoun | 0.53 | 5.85 | 4.46 |

| 3rd-person pronoun | 11.98 | 9.94 | 34.08 |

| Adjectives | 32.22 | 46.36 | 38.35 |

| Adverbs | 23.84 | 48.81 | 52.24 |

| When-adverb | 0.99 | 1.85 | 3.43 |

| Wh-adverb | 1.90 | 3.52 | 6.07 |

| Present tense | 20.94 | 47.85 | 17.27 |

| Past tense | 29.05 | 18.26 | 61.42 |

| Future verb form | 1.84 | 1.86 | 1.99 |

| Infinitive verb form | 19.83 | 27.64 | 32.00 |

| Gerund verb form | 13.03 | 14.71 | 12.02 |

| Participle verb form | 18.73 | 14.64 | 17.91 |

| Predicative complement | 18.02 | 34.20 | 28.92 |

| Figures | 24.24 | 40.87 | 11.67 |

| Features | News | Reviews | Tales |

|---|---|---|---|

| Events (general) | 68.58 | 66.62 | 97.62 |

| Aspectual event | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.82 |

| Intensional action event | 4.18 | 2.85 | 6.41 |

| Intensional state event | 3.35 | 6.49 | 3.89 |

| Occurrence event | 49.77 | 52.29 | 77.51 |

| Perception event | 0.22 | 0.64 | 0.80 |

| Reporting event | 8.69 | 1.66 | 5.37 |

| State event | 1.69 | 2.33 | 2.81 |

| Time links general (Tlinks) | 381.44 | 240.80 | 592.92 |

| Before Tlink | 46.55 | 29.82 | 104.08 |

| After Tlink | 36.90 | 17.12 | 67.02 |

| Includes Tlink | 1.79 | 0.99 | 1.74 |

| Is included Tlink | 15.58 | 5.79 | 9.94 |

| Simultaneous Tlink | 1.93 | 1.66 | 2.77 |

| Vague Tlink | 278.68 | 185.43 | 407.38 |

| Parenthesis sentences | 0.00 | 3.91 | 0.00 |

| Interrogative sentences | 0.21 | 1.75 | 2.42 |

| Exclamatory sentences | 0.06 | 2.21 | 2.85 |

| Nominal subject | 54.09 | 76.02 | 91.69 |

| Direct object | 31.37 | 38.44 | 42.86 |

| Named entity length 1 (NE 1) | 31.12 | 22.21 | 19.79 |

| NE length 2 | 9.97 | 8.46 | 2.34 |

| NE length 3 | 3.46 | 2.00 | 0.43 |

| NE length 4 | 1.30 | 0.66 | 0.12 |

| NE length 5 or more | 0.96 | 0.42 | 0.16 |

| Features | News | Reviews | Tales |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coreference chains | 16.47 | 15.25 | 18.33 |

| Maximal coreference chains | 7.94 | 7.60 | 10.36 |

| Discourse markers (DMs) | 13.05 | 20.74 | 22.61 |

| Time expressions general (timex) | 12.06 | 6.23 | 7.39 |

| Date timex | 6.83 | 2.66 | 3.07 |

| Time timex | 0.74 | 0.66 | 1.29 |

| Duration timex | 4.21 | 2.65 | 2.71 |

| Set timex | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.33 |

| Quotation marks | 6.23 | 0.10 | 12.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maestre, M.M.; Vicente, M.; Lloret, E.; Cueto, A.S. Extracting Narrative Patterns in Different Textual Genres: A Multilevel Feature Discourse Analysis. Information 2023, 14, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/info14010028

Maestre MM, Vicente M, Lloret E, Cueto AS. Extracting Narrative Patterns in Different Textual Genres: A Multilevel Feature Discourse Analysis. Information. 2023; 14(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/info14010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaestre, María Miró, Marta Vicente, Elena Lloret, and Armando Suárez Cueto. 2023. "Extracting Narrative Patterns in Different Textual Genres: A Multilevel Feature Discourse Analysis" Information 14, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/info14010028

APA StyleMaestre, M. M., Vicente, M., Lloret, E., & Cueto, A. S. (2023). Extracting Narrative Patterns in Different Textual Genres: A Multilevel Feature Discourse Analysis. Information, 14(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/info14010028