3. Method

The present research attempts to fill the gap between the theoretical approach of online education and its actual application, which is related to the experience, views and involvement of students in the educational process. At the same time, it attempts to investigate the degree to which the principles of educational neuroscience are utilized in the context of the online education of adult students in evening vocational upper secondary schools of the informatics sector during the pandemic in Greece.

Hence, the study aimed to investigate the following research questions:

How did the adult students of evening vocational upper secondary schools of the informatics sector cope with the technological requirements of online education?

How did the adult students of evening vocational upper secondary schools of the informatics sector perceive their participation in the online education?

To what extend did the adult students of evening vocational upper secondary schools of the informatics sector believe that they had achieved the learning outcomes?

How did the adult students of evening vocational upper secondary schools of the informatics sector communicate with educators and their classmates during the implementation period of online education courses?

To investigate the above research questions, the study was based on the naturalistic paradigm, and a qualitative methodology was adopted. In order to conduct the qualitative approach, a two-part questionnaire was used as a data collection tool. The first part included 15 structured open-ended questions in order to explore the learners’ views on online learning, and the second part included five questions about the demographic characteristics of the participants. The first section contained structured open-ended questions regarding technological requirements, level of participation, perceived achievement of expected learning outcomes, and teacher–student and student communication with their classmates. Three questions focused on technology requirements and technical issues related to online education. Participants were asked if they had the necessary equipment, if any technical problems arose during the online courses and if they were able to use the digital platforms. In addition, there were five questions related to the pros and cons of online education, acceptance or not, students’ preference for synchronous and asynchronous education, and how they experienced the new learning environment. Four questions explored the ability of students to achieve the expected learning outcomes in the theoretical and laboratory context of education, the involvement of learners with the activities and obligations, as well as the way they experienced online teaching. Moreover, three questions focused on the communication within the educators and the classmates, as well as the psychological impact that the online education had on them. The second section included questions about the students’ demographics and academic background, such as age group, gender, level of education, marital and work status. In order to refine the data collection strategies, the questionnaire was piloted with two students. The pilot study did not lead to any substantial modifications.

The research was conducted from 15 November–10 December 2020, when schools in Greece operated either fully online or following a hybrid model and attempted to record students’ views on their learning experience, in order to identify similarities and differences among them. Moreover, it aimed to record the levels of student participation, achievement of learning objectives and the quality of communication among students and teachers, in order to correlate the results with the principles of educational neuroscience. The questionnaire was completed by each student with the online presence of one of the authors. The answers collected by each participant were re-read by the other authors, in order to identify possible incomplete phrases and poorly meaningful sentences. The participants in the research study were all students of the informatics sector of the only evening vocational upper secondary school in a semi-urban island region of Greece. The participants were selected on the basis of their location and the accessibility by the researchers. Those students had experienced the ERT model during the previous school year, throughout the time of the first sanitary measures. Due to the pandemic, the research was conducted via online meetings, whose structure supported the collection of data on all the related issues.

More specifically, the adult students of the evening upper secondary vocational school of informatics sector ranged from 27 to 47 years old. They were 10 in total: 5 women and 5 men. The demographics of the participants are presented in

Table 2. Ten online meetings were held so that each participant could answer the questionnaire on the online presence of one of the researchers. Each student provided answers to all the question of the form.

The study followed the GDPR regulations for data collection and processing as well as the ethical guidelines of the University’s research ethics committee. A consent form was completed by each participant at the beginning of the process. The participation was voluntary and anonymous, and the students were informed that they could withdraw their participation at any time without any consequences. Only the authors had access to the research data.

4. Data Analysis and Results

NVivo software was used to analyze the data. The qualitative study focused on categorizing the findings on the thematic analysis of the responses, on the correlation of the responses with the demographic data, and on the further interpretation of the findings. Each individual’s data were anonymized, and each participant was encoded with a tag from S1 to S10.

Initially, the data were coded and nodes were created. The process started with an interview, and the first nodes were created. Then, from each of the other interviews, either new nodes emerged, or nodes that had already been created were strengthened. The research questions and the answers given by the students were considered in order to create the nodes (

Figure 1).

Nodes are corresponded to concepts, properties, categories or relationships. From the nodes, four categories emerged that consisted of three or more codes (

Table 3). The four categories are (i) technology requirements and technical issues related to online education, (ii) pros, cons and students’ acceptance of online education, (iii) students perceived achievement of the learning outcomes and (iv) teacher–student and student communication with their classmates.

More specifically,

- (i)

Technology requirements and technical issues related to online education.

Concerning the technological needs and with relation to the first research question, nine out of ten learners reported that they were able to meet the hardware and software needs and did not have to deal with related issues, which showcases that they had adequate technological equipment and, more specifically, internet connection and a computer (desktop or laptop) or tablet. It is important to note that the participants in this research are upper secondary students of the informatics sector and, therefore, the use of digital technologies is more than satisfactory. Nevertheless, seven learners stated that during the lessons there were technical problems, such as power outages or internet connection problems, while three learners stated that they had no problems. The answers show that technical problems are difficult to avoid. However, these problems often negatively affect the learning process. Moreover, the learners claimed that they did not face any problems connecting to the online course and said they were able to respond to the online education process (

Table 4). Despite the fact that the participants are adult learners, they were able to fully respond to the technical difficulties of online education. The answers give a similar picture as the one seen from the first question. In other words, it seems that the participating learners, due to their studies, have satisfactory technological skills in the use of digital technologies.

- (ii)

Pros, cons and students’ acceptance of online education.

Regarding the second research question, the findings show that in this new educational context, six of the adult learners in the study preferred the course in the physical learning environment, three learners preferred the online courses and one learner preferred a blended framework with the theory in the virtual environment and the laboratories in the physical learning environment (see

Table 5). Of additional interest is that seven out of ten participants in this research stated that online education gave them the opportunity to increase their participation in the lesson in relation to the lesson in the physical school environment. Two learners had opposite opinion, and one learner (S1) maintained a neutral stance stating: “I feel that it was the same. As I was in the classroom, the same I feel in the virtual classroom. My participation did not increase or decrease”. Adult learners do not seem to reject online education, but instead show interest in it.

Moreover, nine out of ten learners indicated that they prefer synchronous online learning to asynchronous since it gives them the opportunity to attend and engage in the lesson in real time and at the same time cover the needs in the compulsory school hours. As one student (S3) characteristically stated, “I prefer the synchronous form of online education, since we discuss, exchange views, have the teacher with us and do not feel cut off from our classmates. The asynchronous model is largely lonely”. Attempting to re-establish their views on online education, the students identified that this educational approach has significant benefits for them, such as (a) they are at home, (b) they are in a safe environment, and (c) they have the opportunity to continue their education. On the other hand, they referred to the poor quality of the teaching provided, especially for the laboratory part of this. According to S3 “Online teaching was not bad. However, we had a lot of problems with the labs. Workshops could practically not take place other than the programming workshops”. At the same time, the S5 states: “The frame was tolerable. But it is by no means the same as being at school. Often, we did not listen, other times the connection was lost. We would not have these problems at school. Of course, not that we would not have more...”.

- (iii)

Students perceived achievement of the learning outcomes.

As far as the perceived achievement of expected learning outcomes (third research question) is concerned, seven learners stated that they met the requirements of the courses through online education, while three learners answered that they could not cope with this process. Moreover, six learners believed that they understood the lesson and achieved the expected learning outcomes to a high level, while four learners stated that they did not succeed (see

Table 6). However, when the question focused on the laboratory lessons, it was pointed out that despite the differentiated teaching approach to that in the physical lab, six learners stated that they encountered difficulties in attending the laboratories, two learners stated that they were satisfied with the progress of the laboratory lessons, and two learners stated that they maintained a neutral attitude toward the question, as they were not sure about the level of achievement of the expected learning outcomes. The participants’ answers regarding the laboratory’s attendance of courses are related to hardware and software issues. The response of S8 highlights the basic difference: “The programming lab classes went smoothly, although we could not work with our classmates. However, operating systems and networking labs were difficult to complete as needed.” In addition, eight learners answered that they were quite consistent with the assignments and study they had to complete, while two learners answered that they were not consistent. One of them stated that he was inconsistent due to the lack of appropriate technological equipment (he had a tablet, and several specific tasks could not be done) and the second stated that he forgot quite often to complete his tasks. S9 states “The obligation to go to school led me to find time to work from home. Now on the online learning it is different. The lesson ends and I leave aside all the tasks I have to do for school, due to family obligations”.

Two significant findings emerge from the question “Which teaching ways led you to become more involved in the learning process?”. The first is related to the teaching approaches used by the educators and the second to the techniques that encourage active participation. More specifically, three out of ten students stated that they were tired of PowerPoint presentations; two students highlighted the opportunities given to them by educators to work individually and return plenarily to discuss their results; and five students identified that the monologue from teachers led to a passive attitude resulting in non-participation in the lesson. In addition, the students made positive comments about the opportunities given to them for interactive discussion and about the short questions that the teacher asked and had to answer. Moreover, four students identified the post-lesson assignments as positive for online teaching, while five argued that they did not like these assignments, as in the physical learning environment these assignments could be completed in school and so they did not have an additional obligation during their spare time.

Regarding the fourth research question about the communication in the new learning environment, seven out of ten stated that they were satisfied with the online communication with educators. The other three participants did not express dissatisfaction but indicated that they would prefer communication in the physical school environment (see

Table 7). S5 states “I do not think communication was improved. However, I would rather talk to the teachers at school. The discussions we had there were more complete.” At the same time, when asked if it was possible and satisfactory to communicate with their classmates during the pandemic, it seems that students divide communication into two levels: (a) in the context of the lesson and (b) in the context of out-of-school communication. Six learners stated that they did not miss communication with each other since they communicated online, while four learners answered that they lacked contact. S2 states: “After school we communicated via phone, skype and other ways. At school, however, communication decreased. The lesson was done, often we did not exchange opinions and so it was not like before.”. In the same vein, S4 states: “The online classroom has not provided opportunities for collaboration and communication. But we have not lost contact, we communicate after school”. On the contrary, S7 reports: “At school we talked, communicated, exchanged thoughts. Now we are locked in the house and we have no communication”. Concerning the psychological impact that e-learning had on students, eight learners answered that their psychology was unaffected, while two answered that their psychology was negatively affected.

Based on the above, the findings show that the students’ learning experience was partly satisfactory. The students highlighted their efforts to adapt to the evolving pandemic, the new learning environment and the changes in their daily program. The research highlighted that students face similar problems as students from other countries and other education systems. It turns out that the students sometimes found it difficult to secure their participation in the educational process since there were times when they endured negative experiences. They had to manage distractions that detuned them as well as the pessimism they experienced due to the pandemic. At the same time, however, their feelings differ in the subject of laboratory education, where the difficulty they experienced seems more intense.

Further analysis of the data with NVivo software revealed interesting findings. More specifically,

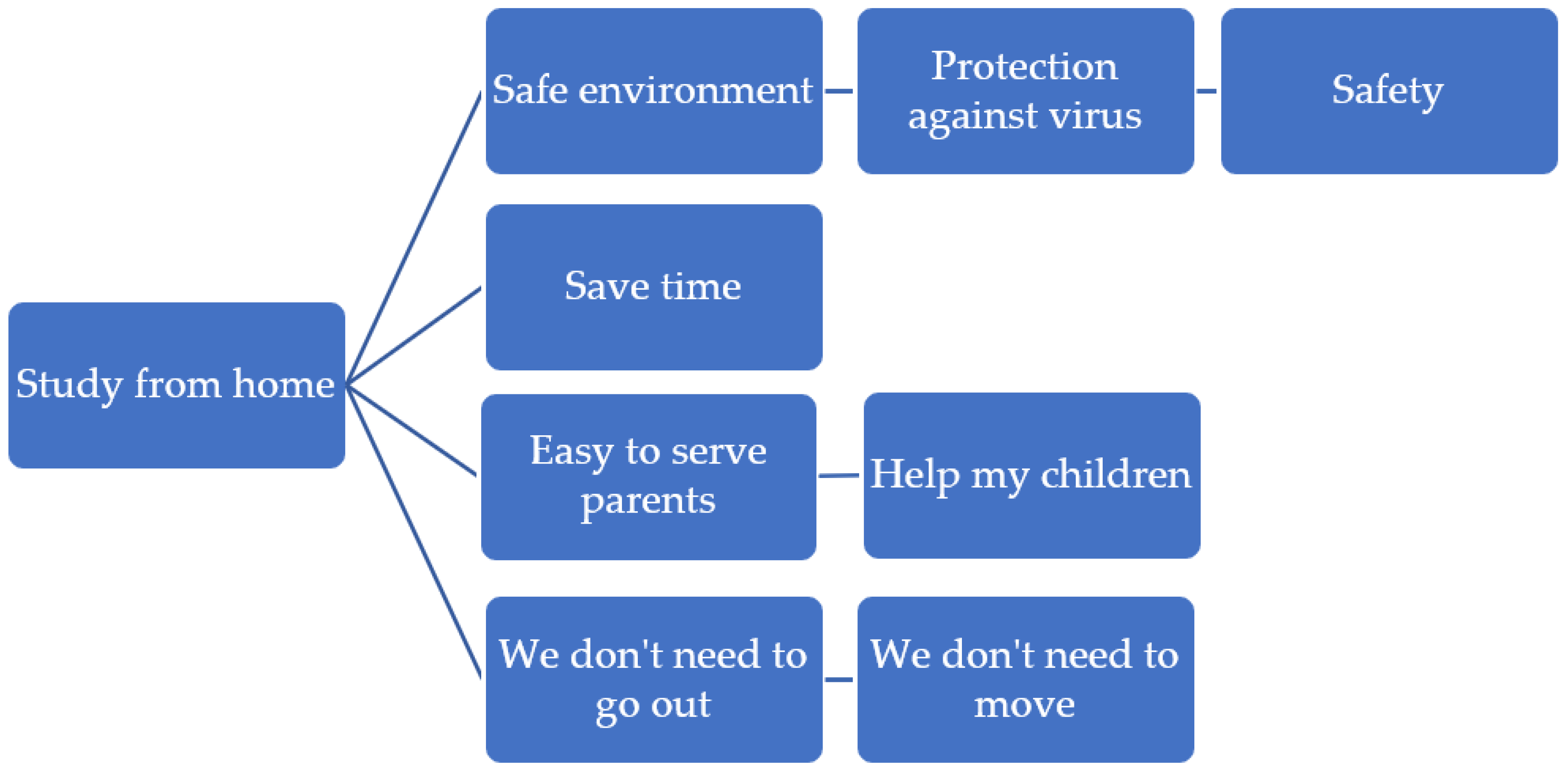

Figure 1 highlights the views of learners in relation to the opportunity they had to participate from home in online education (see

Figure 2). By categorizing the answers, it turns out that there are four reasons why adult students consider that they benefit from the possibility of online course attendance: (a) they do not need to travel, (b) security against COVID-19 is ensured, (c) they save time, and (d) they can take care of their parents and children as adults with family responsibilities. Three out of five women were classified as those who had a positive view about online education, as opposed to men. Of these, S4 and S10, who had a family, found online education to be very helpful, as they had the opportunity to be at home and at the same time they could attend classes and supervise their family. Interestingly, the S4, who is employed, married and the oldest one of all states: “For me, the online education was good and very facilitating, since I have children, and also elderly parents to take care of at home”. On the contrary, the S7 had a particularly difficult time managing the family context, stating: “Everything has increased. Home lessons and family at the same time. For many hours we were all together and at the same time we all had obligations and needs. I would prefer to go back to school”.

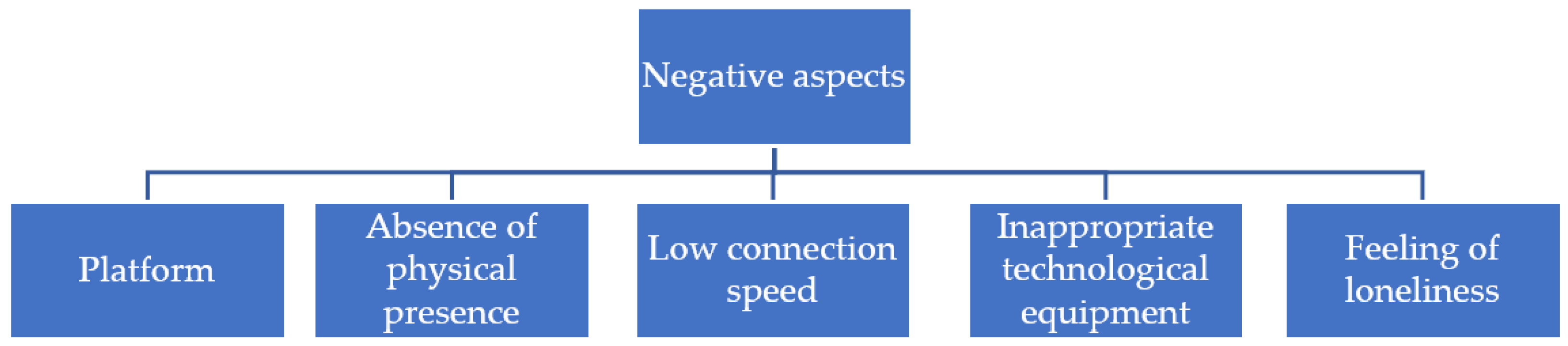

Another interesting finding from the NVivo analysis refers to the negative aspects presented in the participants responses. The most frequently appeared word was the word platform followed by the absence of physical presence, low connection speed, lack of appropriate technological equipment and feeling of loneliness (

Figure 3).

Interestingly, learner S9, the youngest learner, had the most negative views on online learning, stating that “there is not always a quiet environment at home and communication with the educator and classmates was not always direct”.

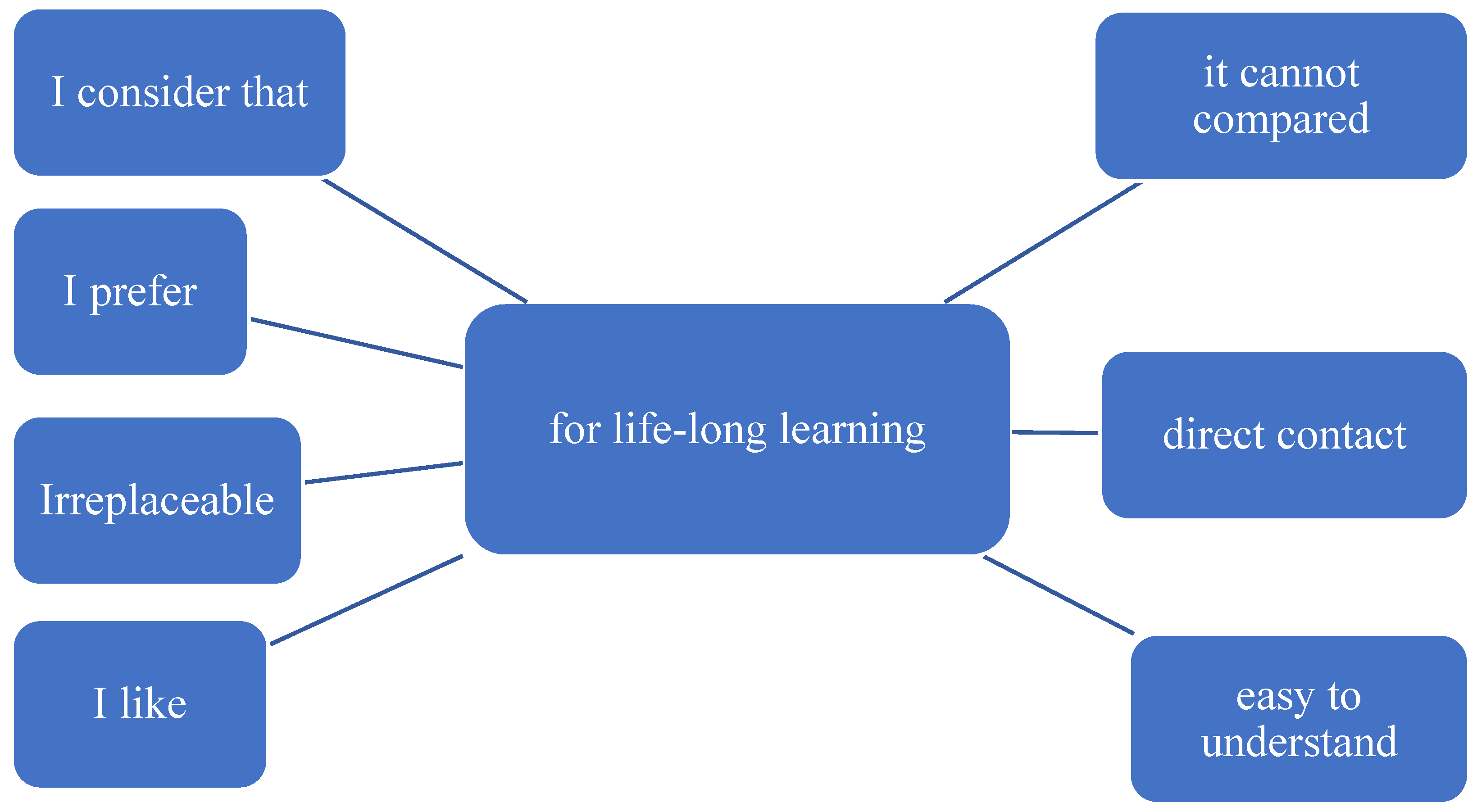

In a similar context,

Figure 4 highlights the learners’ views as they compare online learning with learning in the physical learning environment and identify the reasons why they prefer to be in the physical learning environment. The three learners who prefer the online learning were the learners S2, S4 and S8, who are married and workers. It seems that the online education serves them for professional and family reasons.

Finally,

Figure 5 shows the reasons why learners prefer synchronous online education over asynchronous. From the tree, it seems that synchronous online education provides the opportunity for communication, which was largely absent from everyday life due to the pandemic.

Finally, it is interesting that the students who are employed did not want to have an extra workload after school (which was open in the afternoon) since the next day they had to work both for their job and for the school assignment(s). S4 states: “Working from home and getting them ready for the next lesson was stressful and I could not cope since I had both my job and my family”.

5. Discussion

When schools around the world were forced to conduct online courses in order to continue education and at the same time protect the population from COVID-19 and limit its spread, the implementation of the physical classroom model to the online environment was observed. As a result, the conditions for an optimal learning context (learner’s will, appropriate educational material and appropriate pedagogical approaches) disappear [

37]. The research found that the structure of the online teaching that was applied influenced both the acceptance and the successful learning experience.

The online teaching that was finally offered was an improvised creation of each educator, while s/he tried to transfer the physical classroom to the online environment. This improvisation led to a variety of teaching approaches that changed the way students experienced the learning process, affecting both their emotions and their learning path. Another issue was the forced integration of tools that served as a means of communication and learning. Although technological tools are used in physical education (blackboard, marker, chalk, paper, pens, and computers in the laboratory), the need to use appropriate tools depending on the activities and improvisation of teachers led to a variety of approaches that had a total of positive impact on students’ digital literacy, but at the same time, a negative impact on their learning.

As a result, the students showed low motivation and dissatisfaction with the experience and finally accepted this new model of education as a “necessary evil”. It appears from the present research, as well as at an international level, that the students experienced monotonous or non-interactive lectures [

38], they were taught with the same approach that they met in the physical classroom, without appropriate planning, without exploring the needs and without the experience of teachers to carry out such teaching.

In addition, students faced multiple challenges, such as distraction, communication problems with classmates and their educators, and space issues, as most of the time, the whole family was at home and connected online for either work or educational purposes. Because of these challenges, their experiences were also affected, and their perspective on online education was probably affected, with the risk of having a negative predisposition to the technology education revolution. Although students attempted to be involved in the process, the structures and manner of teaching limited their participation in the learning process. In addition, it appeared that for the students of the present study, the specific model of education did not have a psychological impact. The students referred to isolation, loneliness, but on the other hand, they considered it necessary to protect themselves and their families from the coronavirus.

Concluding from the above, it seems that long-term planning is required for the integration of online education structures in all schools. It is useful for these structures to be consistently offered to students as an alternative process and to be regularly evaluated. The role of educational neuroscience is crucial in designing learning experiences that adopt its principles.

First and foremost, educators’ training in both distance education and educational neuroscience is necessary. The ultimate goal is for each school unit or group of schools to have a special educator who will be able to conduct research within the school units to specify the needs of teachers. Thanks to the results of the research will be able to develop distance learning material in collaboration with his/her colleague. In this way, the learning processes (e.g., structure, duration of lectures) will be standardized and the material repository of each school unit will be developed. This way, students and teachers will be able to refer to it when they need it. This will contribute to learning, thanks to the plasticity of the human brain and its ability to make connections.

In addition, the high level of students’ active participation in the educational process can contribute to their learning. Online learning environments offer multiple opportunities for a variety of activities that can enhance learner’s engagement and are sometimes richer than the education in a physical environment (private chat, group chat, digital boards and breakout sessions) in such a way that learners participate actively and have multiple opportunities to engage in the learning process [

39]. In the context of forming, consolidating, storing and retrieving new knowledge, the educator can take advantage of the digital media offered to perform diagnostic, formative and final assessment. By utilizing evaluation procedures, the teacher can either identify the pre-existing perceptions of the learners, identify whether the learners have the prerequisite knowledge, or monitor the progress of them. Through the use of the digital media provided and the inclusion of frequent but non-threatening assessment, the educator can enhance the learning of the students, as long as it also provides them with appropriate feedback to understand the idea or concept. Brain development can be further enhanced by taking advantage of both the learning barriers that students encounter and by exploiting the cases of not achieving the expected learning outcomes. In order to achieve reinforcement during online learning, learners need to be actively involved in the learning process by negotiating the issues identified by the educator or arising within the group. The aim is to give learners the opportunity to re-examine obstacles (either their own or others’) both individually and collaboratively, to eliminate possible misunderstandings and to achieve the expected learning outcomes [

27].

In the context of online learning, the multidimensional approach can be attempted through a variety of teaching and learning ways. It is important for the educator during the design to integrate a series of problem-solving activities, both open and closed type and of different strategies. In this way, learners will have the opportunity to engage in activities using a variety of approaches. Multiple representations play a special role in physical and online classroom teaching. According to findings in the field of educational neuroscience, multiple representations are a vital component of learning. A multidimensional approach to knowledge provides alternative ways for learners to acquire new knowledge, overcome obstacles and apply this practice in their daily lives [

29].

The need for a differentiated approach per student or group of students is an important component in achieving learning. Hence, the learning environment that includes positive emotional experiences and connections for learners contributes to learning. Learning seems to be enhanced when learners approach concepts and ideas with creativity and flexibility [

30]. Consequently, the learning environment in online learning is important to function in such a way as to provide learners with the time they need to be creative. Technology today provides the means for the realization and implementation of online collaborative actions. The possibility of utilizing virtual rooms is one of the means that can enhance the collaboration between learners [

40,

41]. In the online classroom, collaboration between learners is important for two reasons: (a) it allows them to share their concerns, ideas and successfully study the problem given to them, and (b) it helps them to understand and recognize how other people work.

All of the above lead to the need to further enhance the readiness of teachers so as to be able to adopt the principles of educational neuroscience. The students’ answers show that once the technical issues have been overcome and everyone has the necessary technical equipment, it is important to focus on learning in the context of the online environment. It is shown that online educational environments can operate based on the principles of educational neuroscience, so that active learning is a fact, assessment is integrated, a multidimensional framework exists and collaborative teaching is substantive.