Abstract

The objective of this research is to develop a methodology that allows the construction of a standard of knowledge management and technological innovation applicable to the field of the universities in Mexico, the use of which results in better use of their resources and the improvement of their productivity. The analysis is carried out based on the systematic integration of the knowledge management and innovation models published in recent years, as well as the results of the experiences that propose standards for knowledge management and innovation. The results found are that knowledge management favors and facilitates innovation in organizations and allows them to offer better products and services. These findings are with the application of a methodology and an instrument to measure the maturity of the organizational structure. The application of the evaluation instrument was applied in a single organization. However, it can be considered a case study that empirically contributes to the state of the art of knowledge management. Organizations need to become aware of the high value of the knowledge and experience in various fields of the people who participate in them. It has been observed that the participation of experts facilitates the achievement of organizational objectives and favors knowledge management and innovation. This study provided information and experiences of an administrative nature to a higher education institution, which allowed an improvement in strategic decision-making, the promotion of technological developments, and the improvement of internal processes that lead to greater effectiveness of the academic and research processes.

1. Introduction

The concept of innovation refers to a wide range of actions, products, and processes such as the improvement of administrative, planning, and programming systems, production processes, and the development of new products or the improvement of existing ones [1] Innovation is often associated with increased productivity, that is, with the reduction in the amount of physical work necessary for the production of goods and services [2]. This process, however, is not limited to the organization but rather involves interactive processes with external agents, such as customers, suppliers, and users.

As the paradigms in the creation of value have been changing toward a digital economy and transformation, society has had to modify its thinking schemes and consider new elements for the creation of value. Innovation has always been present in the history of humanity [3] because, through it, products and services have improved, benefiting users, consumers, companies, organizations, the ecosystem, and society.

The basis of innovation is organizational learning because it is the way to increase the knowledge of the company. The more knowledge is shared among the employees of a company, the greater the capacity for innovation. Consequently, the exchange and dissemination of knowledge facilitate innovation [4].

Innovation is therefore extremely dependent on the availability of knowledge [5]. However, the structure of knowledge production is today more complex and geographically more dispersed than ever [6], which forces to implement some degree of knowledge management and administration to achieve that innovation is successful.

Although it comes from knowledge, innovation cannot be the mere reproduction of accumulated knowledge; it is, without a doubt, the search and use of new and unique knowledge. We can reasonably say that innovation is the result of organizational knowledge management.

The research on which this document is based aimed to develop a methodology that would lead us to build an indicator of knowledge management and technological innovation applicable to the field of organizations in Mexico. For this reason, the research questions were: Will it be possible to explain knowledge management and technological innovation (KMTI) based on the factors included in the indicator proposal? What type of factor is the most significant for KMTI?

The article is made up of six sections: in addition to this introduction, which briefly addresses the background, objective, and research questions, the second section contains the methodology and describes the elements, stages, and criteria used to carry out the study; the third section addresses the theoretical framework and a review of the relevant literature is made; The fourth section shows the results obtained, both from the construction of the indicator and its pilot application in a public organization, the University of Guanajuato, Mexico; The fifth section contains the discussion of the results, emphasizing the usefulness of the information for the implementation of technological projects that lead to greater administrative and organizational efficiency. Finally, the conclusions derived from the investigation are included.

2. Materials and Methods

The research method that we have followed has been carried out from the neopositivist paradigm. In this context, the main conceptual and methodological constructions have been approached from the management approach, with special emphasis on organizational strategies. Likewise, due to the very nature of the object of study and the studies prior to this work, conceptual references have been adopted from the area of computer science and software development [7,8].

This investigation is of a transactional type because the data collection has been carried out in a single moment. It is exploratory-descriptive [9,10] and not experimental because a single evaluation instrument has been defined, built, validated, and implemented, which allows a direct approach to the object of study [7,8].

The methodological approach of this work is also based on an in-depth quantitative study depending on the purpose of the research.

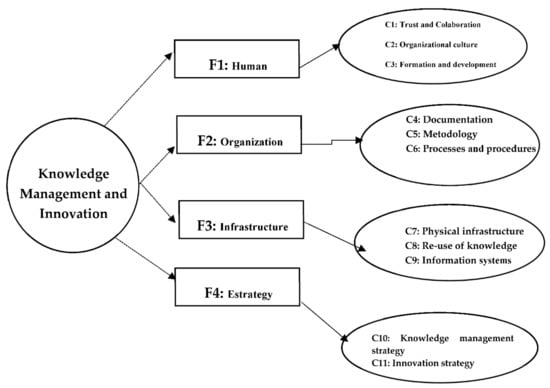

Based on the analysis of different models on knowledge and innovation management, a Mexican standard for knowledge management and technological innovation was designed based on the four main types of factors that, according to the academic literature, affect the management of knowledge: (1) human factor, (2) organization factor, (3) infrastructure factor, and (4) strategy factor.

Likewise, an own standard model was proposed and a proposal for its measurement (Figure 1) to support the theoretical and conceptual development of this research and, at the same time, allow the empirical validation of the research assumptions, as well as the knowledge management and technological innovation standard that is described and proposed in this research.

Figure 1.

Proposed measurement model.

In a first approximation, both the objective and the scope of the evaluation instrument are defined. Then, the items were constructed from the relevant literature on the subject. Finally, the theoretical and conceptual validation of the elements and components of the evaluation instrument is made. In addition, comments and suggestions from experts in the field were heard [9].

The evaluation instrument is made up of 83 items or statements that were used to inquire about the different types of components that constitute each of the factors studied (human, organization, infrastructure, strategy).

The validation of the instrument is performed in three phases: in the first, the evaluation instrument is presented, and the confidentiality of the responses is declared; in the second, the general information of the participant is obtained (education, type of position, assignment, seniority, among other issues) and, in the third, the items of the factors described in the research model are questioned. These items are questions that are answered on a seven-point Likert scale, which is the most recommended in this type of study [10]. On the scale, 1 represents “totally disagree” and 7 represents “totally agree”.

For the sample design, a set of characteristics that facilitated the application of the evaluation instrument were considered. Among the characteristics considered are the following.

- It was defined that the institution analyzed with the instrument would be a public university because knowledge is intensively produced in them [11], and some type of management is necessary in this field so that the natural generation, regeneration, and accumulation of the knowledge leads to the development of innovations [12];

- The one selected was the University of Guanajuato, an organization with more than 5000 employees;

- It was defined that the specific area where the implementation of the evaluation instrument would occur would be one whose presence is indispensable in most organizations, regardless of whether it is a public or private organization. For this reason, the evaluation instrument was applied in an area of high management of the administration of institutional resources. This area offers very important support to the university in substantive functions that provide various services for the proper development of academic activity. The support offered by this area to the university ranges from technological services to financial services, including support for information and communication processes, planning, as well as support for some processes of promotion and assignment of academic stimuli. It is an area subject to strict regulation and constant audits of the most diverse nature that makes it difficult for it to develop high levels of organizational innovation.

As a control mechanism, in the first stage, information was collected provided by the immediate bosses of the potential participants. This information was compared with that collected in the application of the instrument, which added greater reliability to the profile of the participants. The sample was 218 workers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Stages of database debugging based on the sample design.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

For the application of the instrument, it was decided to use the Qualtrics® software because it allows the realization of the application online, the export of results in Excel and in CSV (comma-separated value) format, which facilitates the analysis, monitoring, reporting, and the availability of real-time response on the multiplatform. Data analysis was performed with SPSS® software.

2.1. Theoretical Framework

This section addresses the role that universities play in generating knowledge and innovation, as well as the robust literature on the influence of these processes on the development of organizations. The Mexican standard for knowledge management and technological innovation is also presented.

2.1.1. Knowledge Management Models

There are multiple proposed models of knowledge management, [9] only analyzed 160 of them, normally these models are associated with the general process of knowledge management, already explored by different authors [13,14], there are even models of knowledge and technology transfer [15].

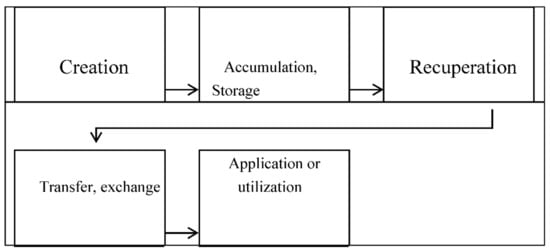

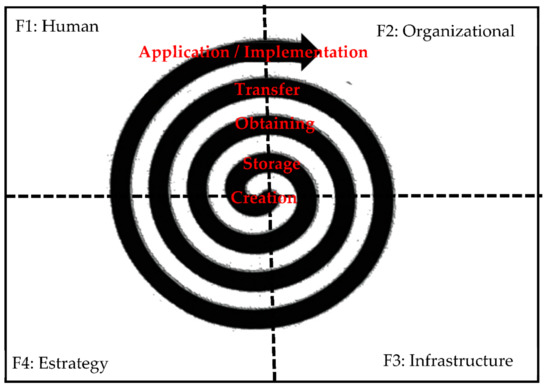

Typically, these models integrate the phases of creation, accumulation, recovery, transfer, and application of knowledge (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Knowledge management process (KMP). Source: own elaboration, adaptation of the proposal of [13].

Consequently, it is possible to observe in the academic literature the agreement on the statement that it is not the amount of existing knowledge at a given moment that is important, but rather the ability of the company to effectively apply existing knowledge to create new knowledge [16,17] in such a way that knowledge management encourages innovation [18,19].

Thus, KM involves activities related to the capture, use, and exchange of knowledge by the organization and is an important part of the innovation process [20] From its origins, it has been an element that can contribute to achieving the objectives of the organization by putting at its service what people know, their experiences, and their abilities [21,22,23]. Undoubtedly, today more than ever, it is necessary to manage what we know [24], and it is important to ensure systematic management of knowledge [9] in organizations.

As has been pointed out, there is a great diversity of knowledge management models [9,25,26,27]. To facilitate understanding, they have been grouped in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics found in knowledge management models.

2.1.2. Knowledge and Innovation

The concept of innovation encompasses new technologies for production processes, new administrative structures or systems, and new plans or programs belonging to members of the organization [1]. Innovation is often associated with increased productivity that reduces the amount of physical labor required to produce goods and services [2], but it is not limited to the internal borders of the organization but involves interactive processes, in which organizations interact with external partners, including customers and users [29].

The basis of innovation is organizational learning because this is the way to increase knowledge of the company. The more knowledge is shared among the employees of a company, the greater the capacity for innovation will be [30]. Consequently, the exchange and dissemination [4] of knowledge facilitates innovation [31].

An innovation is fully achieved when it is integrated and combined with prior knowledge [29]. However, innovation in the knowledge-based economy cannot mean the mere reproduction of knowledge [32]. The innovation process is commonly equated with a permanent search for the use of new and unique knowledge [23]. We can reasonably speak of knowledge management and innovation; as a result of the effective management of organizational knowledge [33].

The innovation process relies heavily on knowledge, particularly since knowledge represents a much deeper domain than simply that of data, information, and conventional logic.

Innovation management [34] and knowledge management [21,23] go hand in hand by providing a space where learning is simple and continuous. The role of KM and innovation is generally to amplify and accelerate the creation of value for the organization, even more than any strategy or business model.

KM processes could positively affect innovation [4]. Innovation has become one of the key priorities for organizations that want to achieve a competitive advantage [35]. Through the codification of the acquired knowledge, its reuse, storage, refinement, and improvement, organizational innovations can be generated [36].

In sum, derived from the analysis of the relationship between knowledge management and innovation, it is possible to point out the following:

- Good knowledge management encourages innovation [37];

- The knowledge required for innovation is distributed within organizations (across all geographically dislocated functions and business units) and across organizations (for example, through IT vendors, consultants, and involved companies) [38];

- A suitable KM allows continuous improvement of products, services, and cost reduction [39];

- KM processes could positively affect innovation [4];

- Through the codification of the acquired knowledge, its reuse, storage, refinement, and improvement, organizational innovations can be generated [36];

- Through knowledge management and innovation, a sustainable competitive advantage can be achieved [35,40].

A healthy organization generates knowledge and uses it. As organizations interact with their environments, they absorb information, convert it into knowledge, and carry out actions based on the combination of that knowledge and their experiences, values, and internal norms. Without knowledge, an organization, paradoxically, could not organize itself.

Innovation has become an imperative in our days [41]. Their presence is a strategic component of the development of organizations [42,43] and the economic growth of nations. Organizations must be able to propose new models for doing business, modify their organizational competencies and create or provide new capabilities to their members.

It is a reality that innovation has accelerated, and that competition is increasingly difficult and more global [17]. Innovation, as a dynamic process, crystallizes due to the accumulation of knowledge that occurs through learning and interaction.

Thanks to knowledge management, it is possible to detonate administrative, market, technological, and organizational innovations [44] that favor the achievement of the organization’s objectives. Innovation and knowledge creation are a virtuous circle, an indissoluble pairing [21]. This can be seen in Figure 1.

“Innovation is based on the ability to generate and use knowledge, focus it towards solving problems and introduce the solutions that emerge in the market. In this way, innovation contributes to productivity, which in turn drives competitiveness” [45].

Innovation management [34] and knowledge management should be practices of the same process where learning is simple and continuous. The role of knowledge and innovation management is, in general, to amplify and accelerate the creation of value for the organization, even more than any strategy or business model.

As the relationship between knowledge and innovation is wide and profuse, its attention by organizations is a necessary (although not sufficient) condition to achieve organizational objectives. Innovation, as a dimension of knowledge management, occurs through the application of knowledge and the creation of new knowledge [46].

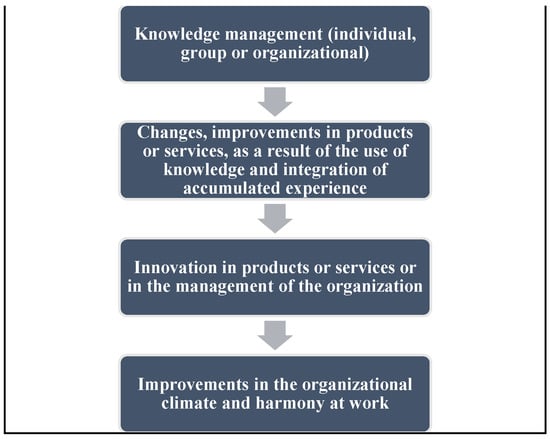

Innovation has therefore been seen as an externality, as a by-product, as a benefit, of knowledge management, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Innovation as a product of knowledge management. Source: self-made.

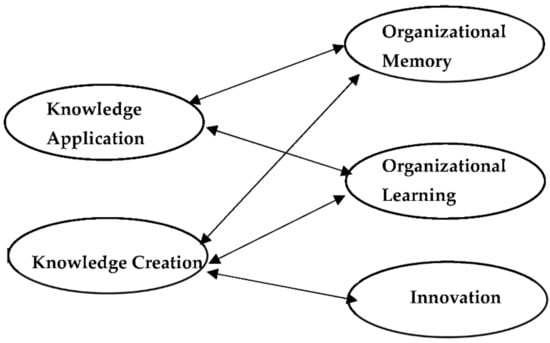

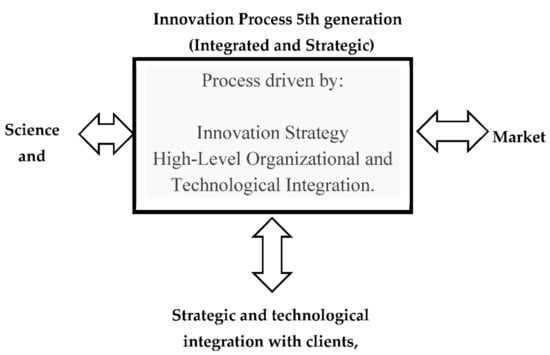

Dodgson’s model (Figure 4) considers innovation a strategy that occupies the central place in the technological and knowledge integration processes. The condition for the operation of this strategy is a high level of organizational and technological integration since technology, by itself, does not produce innovations. It is the high organizational levels that promote innovations and generate interactions between users, providers, creating innovation communities and networks in organizations.

Figure 4.

Relationship between creation and application of knowledge and innovation. Source: [46].

It can be concluded, in summary, from the knowledge management-innovation relationship, that good knowledge management encourages innovation and that the knowledge necessary for innovation is disseminated within organizations, in their functions, and in the units of geographically dislocated business; that it is also disseminated among organizations such as IT vendors, consultants, and the companies involved; that good knowledge management allows continuous improvement of products, services and cost reduction [39]; that technology management processes could positively affect innovation [4]; that organizational innovations can be generated through the codification of acquired knowledge, its reuse, storage, refinement and improvement, and that a sustainable competitive advantage can be achieved through knowledge management and innovation [35].

Two sources of innovation are identified: on the one hand, research, and development (RandD) processes and, on the other, existing knowledge. Therefore, innovation must be understood as a much broader set than the generation of new knowledge through RandD since it includes many other actions both in the productive sector and in the coordination of various economic and social actors, both public and private [47].

2.1.3. The Role of Universities in the Generation of Knowledge and Innovation

Although innovation was initially associated with the productive sector, today, all approaches recognize that universities, research centers, companies, the government, the legislature, financial institutions, and intermediary organizations that promote it are basic actors that participate in innovation systems [45].

Universities and research centers have played an important role as agents of economic and social development since the second half of the 20th century. However, as universities and public research centers have increased their capacity to generate new knowledge, both in quantity and quality, the demand for a return has been increasing for the benefit of society that makes possible the activity of research, mostly through public budgets earmarked for this purpose. Thus, society has improved the perception of the role of academic institutions and their tasks, but the demand for them has also increased.

In modern economies, the valuation of knowledge has increased the relevance of university research as a source of innovation and, therefore, of competitiveness. Pressure for educational institutions began to gain momentum during the 1990s as an explicit obligation of universities, not only due to the appearance of new fields of knowledge with high commercialization potential but also due to the reduction in public support, which has raised the need for alternative sources of financing [48]. Universities, often with traditional structures and strategies, are challenged to fulfill this mission effectively.

The higher education system in Mexico is very broad and ranges from public universities to private research centers, forming a great system that contributes and interacts in regional innovation ecosystems.

The university will have an impact on regional, national and global development, not only by providing competent graduates but also with the interactive creation of technology and innovation in its field of action. This policy of interaction and contribution is what drives the creation of fourth-generation universities.

In this framework, the University of Guanajuato contributes strongly to the development of research by improving impact indicators, although the transition from research to innovation has not yet been completed.

Although, as Reichert [49] says in his work on the role of universities in regional innovation ecosystems:

“The Fourth Generation University pursues a less explicitly linear vision of innovation. Here, innovation is jointly pursued by triple helix partners in common spaces and institutional frameworks, to address the challenges prioritized by all partners. This innovation is possible thanks to previous institutional changes: greater autonomy, interdisciplinary organization, collaboration structures, teaching and learning reforms, expanded services, as well as government incentives and a greater openness of companies to interact with external partners in open innovation.”

In this sense, this work has focused, in the first instance, on measuring the maturity of knowledge management and how it contributes to the generation of innovation, specifically analyzing the organizational and institutional contexts in order, based on this information, to define strategies and actions that are transformed into processes and technologies that institutionally enable a better context for the contribution to the state innovation ecosystem.

In Mexico, these fourth-generation universities are beginning to emerge with interactions that are still incipient because there are internal and external factors that inhibit them, but they promise to be the leading institutions in this new decade.

In this document, only the internal processes of administration and services that serve as support to the function of Third Generation Universities are analyzed, which guide their research and use it as an input for the teaching activity [49].

To motivate universities to advance toward this fourth generation, there must be policies and strategies that guarantee the transfer and interaction of research products toward the regional innovation ecosystem, with more agile administrative and legal processes, which facilitate researchers and students the formalization of contracts, agreements, registration of intellectual property, acquisitions, tenders, security, use of administrative information systems and, of course, a functional and well-prepared organizational structure.

2.1.4. Mexican Standard for Knowledge Management and Open Innovation (MSKMOI)

A standard could support organizations to identify the various variables that affect the best use of their resources, as well as to establish, based on objective measurement, the best strategy to gain knowledge and improve their administration to achieve innovation in your products, processes, or services.

Figure 5 shows a standard model with a spiral like the one proposed a few years ago by Nonaka and Takeuchi [23] for knowledge creation, project management, and, more recently, for software development. The last turn of the spiral represents the implementation of knowledge, that is, innovation.

Figure 5.

Dodgson model. Source: Dodgson et al., 2008.

The proposed model has four quadrants that consider the four factors under study: human, infrastructure, organization, and strategy. These factors have been observed and validated by different authors [9].

The maturity of these factors leads the organization to develop and materialize knowledge management and innovation [50].

Next (Table 4), each of the factors (F) that affect knowledge management are analyzed: (1) human factor, (2) organization factor, (3) infrastructure factor, and (4) strategy factor [9] and the components of each of them (shown in Figure 1). This analysis is carried out through the stages that are commonly shown in Figure 5): creation, storage, obtaining, transfer, and application of knowledge [14].

Table 4.

Description of the factors and their components integrated into the proposal.

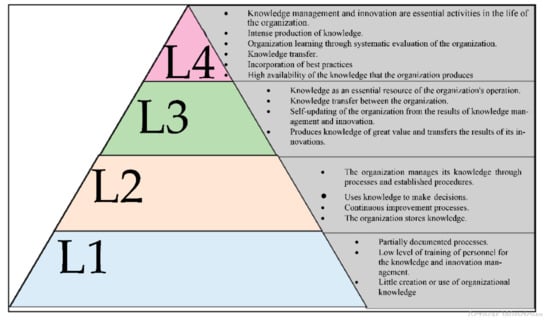

The levels that have been defined for the proposed standard have been derived from previous work carried out in the academic world [72], from the gradual nature that is normally observed in knowledge management and innovation, and from the approach that is commonly observed it is associated in other models, such as the assessments of the levels of the technology readiness level (TRL) and the models of generation or production of knowledge, originally proposed.

In Figure 6, the model’s measurement proposal was developed around four levels: basic, intermediate, advanced, and expert.

Figure 6.

Proposed knowledge and innovation management model. Source: self-made.

3. Results

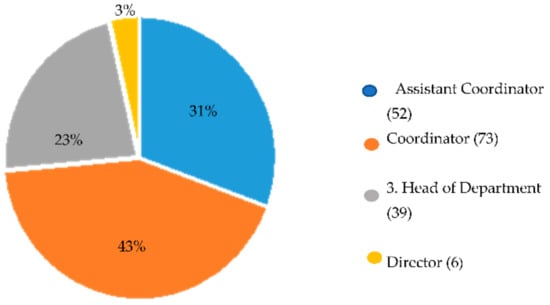

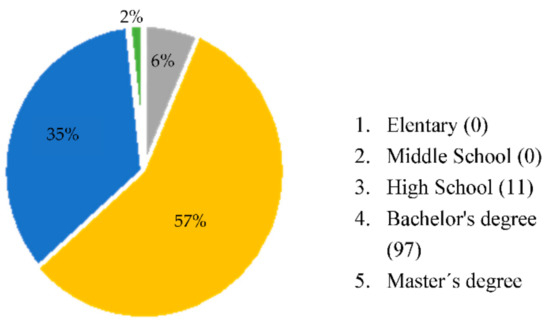

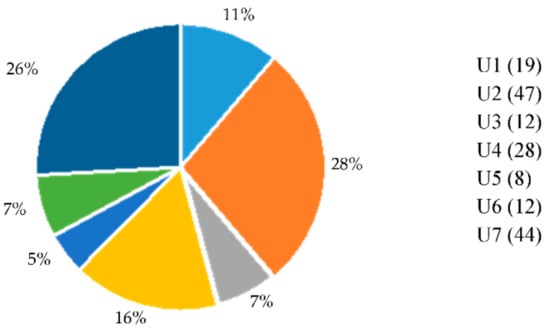

The participants in the sample on which this study is based are people who have an average seniority of nine years in the organization. The summary of the information on the type of position, the administrative unit of assignment and the academic degree is presented in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 7.

Summary of the elements that characterize the levels of the MSKMTI. Source: self-made.

Figure 8.

Participation by type of position. Source: self-made.

Figure 9.

Participation by level of studies. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 10.

Participation by administrative unit. Source: own elaboration.

The number of participants in the sample guarantees a good representation of all potentially eligible areas to answer the evaluation instrument. These areas, as mentioned before, are related to the management of technologies, purchases, infrastructure, financial resources, human resources, the health system, and the organization’s top administrative management.

In total, the participants come from 12 positions classified according to the tabulator, the functions, and the responsibilities that emerge from the organizational manuals. In particular, the organization’s trusted personnel tabulator was used to classify the positions of the participants, which is shown below.

- (a)

- Factorial analysis

The evaluation instrument identified the main components that confirm the theoretical framework used and the four factors evaluated in the proposed research model.

In this analysis, the correlation between the items allows them to be reduced and grouped into factors (factor reduction) where, if the items were not associated, the value assigned to them would be close to zero.

The exploratory factor analysis was carried out, and the main factors of the instrument were identified (F1: F4), which confirms the theoretical framework used and the four factors evaluated in the proposed model. The items that make up the factors of the proposed model are reflected in the factor analysis and confirm the theories used as a reference to generate the evaluation instrument.

It should also be mentioned that some criterion confirmation exercises were carried out using different control variables. It is observed, as a conclusion, that the criterion is confirmed and the factors are built according to the proposed model.

- (b)

- Analysis of correlations between the study items

It is confirmed that there are eight items found through the study of correlations. These items confirm some research assumptions. The items belong to different categories of factors identified by number in the evaluation instrument: (a) organization factor starts with item 10; (b) infrastructure factor start with item 11; (c) human factor starts with item 12; (d) strategy factor start with item 13. It has been decided to keep the items that have a correlation greater than 0.7, as suggested in the academic literature. The explanation of these relationships is described in Table 5.

Table 5.

Correlation study.

- (c)

- Structural analysis of equations

This analysis is based on a second-generation technique for data analysis in social research. It is common when it comes to validating factors that are commonly associated with phenomena that are not observable to the naked eye and that, therefore, it is necessary to build a model for the interpretation of these relationships [73,74].

The designed model only contemplates levels three and four of the MSKMTI and the 47 items that constitute them (Table 4) because it is there where the object of study of this research occurs. It was wanted to observe how the various factors proposed in the research model are related and affect knowledge management and innovation.

Consequently, it can be observed in the table that factor 4 (Strategy) is the one that has the greatest weight on knowledge management and innovation (0.968). These weights, distributed in this way, show that it is necessary to have a strategy that is the supporting element and that is decisive for both knowledge management and innovation in organizations to occur. In this sense, the use of strategic planning tools that favor the achievement of organizational objectives has allowed the combination of all the revised concepts to converge in a proposal that today is materialized in the proposed standard.

The results of the model can be summarized in the following points: (a) It is possible to explain the management of knowledge and innovation from the factors proposed and observed through the EMGCIT; (b) The strategy factor stands out to be the most significant for knowledge management and innovation in the context of this study, and (c) It is possible that the human factor has less incidence in the higher levels of the standard as a consequence of the automation of processes and the use of technologies at all levels of the organization.

- (d)

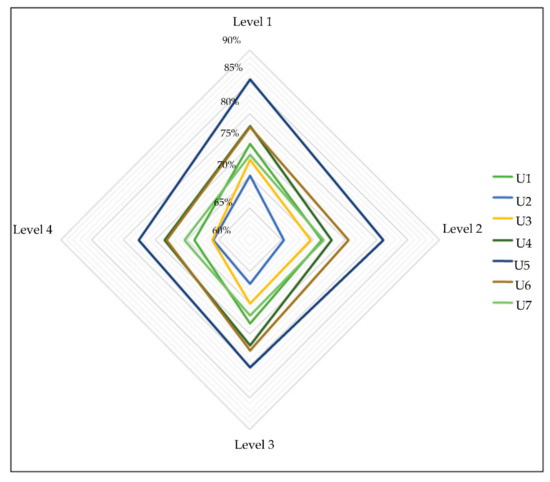

- Analysis based on the levels proposed in the standard

To carry out this analysis, it was decided to use the Likert scale (seven points), assuming that the value 7 corresponds to 100% in the EMGCIT levels. In this way and observing the characteristics of the participants in this study (organizational unit, U), individual evaluations have been obtained of the degree of approximation to each of the levels proposed in the standard by the organizational areas involved.

Observing the Table 6, it can be concluded that the organizational unit that had the greatest scope at all levels was 5, which may be due to the preparation and continuity in the work permanence of the members of the unit and the high demand for quality in the service that is offered. It should be considered that in this unit, there are standardized processes, intense production of knowledge, fostering organizational learning, constantly updating the staff and its members have, on average, a high degree of academic preparation.

Table 6.

Organizational units: compliance with the MSKMTI.

It can also be seen that Unit 2 is the one with the worst performance. For this reason, it is necessary to use strategies that gradually allow you to rise to higher levels in the standard.

Figure 11 presents a visual summary of the scope of each of the organizational units, as well as the comparison between them in relation to the MSKMTI levels.

Figure 11.

Scope of the units with respect to the EMGCI. Source: own elaboration.

Organizations, in addition to implementing the standard, must develop strategies to make use of knowledge management for the benefit of innovation translated into culture and harmony in organizations.

One of the results of this work is the construction of an instrument that, developed in the form of a standard, of gradual and differentiated application, facilitates Mexican organizations the search, within their context of influence and performance, of a better level within the standard. This would allow them to deploy strategies and actions to enhance the creation of knowledge and development of innovations, as summarized in Figure 6.

From this study, the improvement of some strategies and actions that had already been carried out was accelerated, such as the professionalization and development of personnel, optimal technological equipment, as well as the acquisition of specialized software for the automation of processes and key tasks.

In particular, from the generation of an adequate collaborative environment, the participation of the various work teams in external calls was fostered and encouraged, where projects were presented to underpin knowledge management and technological innovation.

A specific result was the support of Conacyt (National Council of Science and Technology) to two projects to obtain resources with the objective of creating a repository of information and digital data for the management of knowledge through collections made up of the academic production of the university community for preservation, access and dissemination purposes.

The specific cases on the effects of the project were the following: first, the favorable participation in a project called to “Provide solidity and integration of elements to the Institutional Repository project of the University of Guanajuato”; second, the strengthening of institutional data centers to improve the management and security in the use of the information that is generated; third, the consistent support, by the university, since 2015, of an investment budget to expand and strengthen the Institutional Information Network that links the various university campuses; fourth, the creation of its own Intranet supported in the framework of the ANUIES TIC 2019 call; and fifth, the achievement of two other awards in 2020, on “Comprehensive Management of Public Works of the University of Guanajuato” and on “Transparency Platform of the University of Guanajuato” (Table 7).

Table 7.

Actions and achievements obtained by the University of Guanajuato.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

With the results obtained in this research, a line of application and research has been left open to compare, in other organizational contexts, both the model and the proposed standard, thus taking advantage of previous experience to improve the new application. The instrument is currently being adapted to test, over the course of this year, the effectiveness of our proposal in at least two different contexts.

This study provides indications of the positive effects that can be obtained in an organization, as reflected in the actions undertaken by the University of Guanajuato and the achievements obtained through them. However, there is a strong limitation in research in public higher education institutions, as is the case of the organization studied here. However, this allows us to verify that, in this area, knowledge management and technological innovation support the decision-making of the administration and contributes to improving the use of its resources and its productivity.

These results are not perfectly generalizable to all areas since the way in which companies and organizations operate is different in contexts, regulations, economic exchanges, etc.

Like all research work, it is a proposal capable of being improved in the sense that in the academic field, there are no endpoints or immutable truths. However, we seek to contribute to the leveling of knowledge management and innovation capabilities that allow Mexico to match what is happening on the international scene in terms of improving the productivity and competitiveness of organizations.

In this research, a methodology was developed to build an indicator of knowledge management and technological innovation applicable to the field of organizations in Mexico. For its test, the University of Guanajuato was selected as a representative public institution in the Mexican context in the field of knowledge generation.

However, an open mind toward knowledge management and innovation is required for the methodology to improve the use of resources and organizational productivity in institutions that are dedicated to the creation, preservation, obtaining, application, and dissemination of knowledge.

For organizations to adopt the standard, the generation of policies and strategies focused on that objective is urgent. Other organizations, such as the High Tech Industry Association, Ministry of Labor, Secretaries of Economic Development, and others, could value the use of a standard such as the one proposed here in their partner organizations.

The results obtained with the application of the standard allowed us to explain the management of knowledge and innovation from the factors proposed and observed.

In the context in which the study was carried out, the strategy factor stood out as the most significant for the achievement of the purposes, while the human factor had less impact on the higher levels of the standard, possibly because of the automation of processes and the use of technologies at all levels of the organization.

The application of the standard should be recommended in a varied set of public and private organizations, for profit or social purposes, and government agencies that allow validating and comparing its effectiveness in different application contexts.

As knowledge and innovation are global strategic components, it is necessary for organizations to become aware of the high value of having people who have knowledge and experience in various fields and whose contribution –not only monetary– facilitates the achievement of organizational objectives.

It is necessary to develop permanent institutional training programs for all members of the organizations. This would contribute not only to the self–preservation of knowledge but to the motivation and personal and professional growth of its members.

Generating “communities of practice”, in all its manifestations (courses, workshops, blogs, wikis, etc.) allows the dissemination and obtaining of new knowledge and fostering innovation.

There is no magic recipe for creating perfect innovation ecosystems, but it is possible to help create incentives for organizations to improve their innovation and knowledge management practices.

To the extent that organizations consciously and proportionally value each of the components of the standard, they will generate strategies to measure the contribution they have in achieving the objectives of this.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C.I.-L. and J.A.R.-H.; methodology, R.A.R.-C.; A.V. defined the database and performed the analyzes in the software that was used; the research design was carried out by J.A.R.-H. and R.A.R.-C., as well as the design of the survey and information gathering; P.C.I.-L., writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing; the work was supervised by J.A.R.-H.; the project administration was carried out by R.A.R.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, and the APC was funded by Universidad de Guanajuato.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://ugtomx-my.sharepoint.com/:f:/g/personal/pc_isiordia_ugto_mx/ElEWI231s1VBsGin9uKIVAkBXRqhRmxUsG1NnLGEyGOHxg?e=Fkwdn6 (accessed on 10 April 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dalkir, K. Knowledge Management in Theory and Practice; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Coad, A.; Segarra, A. Firm Growth and Innovation. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 43, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, N.Y. De Animales a Dioses. Una Breve Historia de La Humanidad; Debate, E., Ed.; CIAD: Madrid, Spain, 2014; Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/jatsRepo/417/41755135015/html/index.html (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Darroch, J.; McNaughton, R. Examining the Link between Knowledge Management Practices and Types of Innovation. J. Intellect. Cap. 2002, 3, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf Al-Aama, A. Technology Knowledge Management (TKM) Taxonomy. VINE 2014, 44, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIPO C.U.I. The Global Innovation Index 2020: Who Will Finance Innovation? Cornell Un.: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-2-38192-000-9. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_gii_2020.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Corbetta, P. Metodología y Técnicas de Investigación Social; McGraw-Hill: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Sampieri, R.F.-C. Metodología de La Investigación. 2015. Available online: https://www.uca.ac.cr/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Investigacion.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Heisig, P.; Suraj, O.A.; Kianto, A.; Kemboi, C.; Perez Arrau, G.; Fathi Easa, N. Knowledge Management and Business Performance: Global Experts’ Views on Future Research Needs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 1169–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K. Investigación de Mercados, 5th ed.; Pearson Educación: México City, Mexico, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Makani, J.; Marche, S. Towards a Typology of Knowledge-Intensive Organizations: Determinant Factors. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2010, 8, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, H.; Valle, C.; Peralta, G.; Farioli, M.; Giacosa, L. Entrepreneurial and Innovative Practices in Public Institutions; Leitão, J., Alves, H., Eds.; Applying Quality of Life Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-32090-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Lee, K.; Lee, S.; Kang, I.W. KMPI: Measuring Knowledge Management Performance. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Liang, P.; Tang, A.; van Vliet, H. Knowledge-Based Approaches in Software Documentation: A Systematic Literature Review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2014, 56, 545–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, E.R.V.; Rodríguez, S.E. Knowledge and Technology Transfer Relationship between a Research Center and the Production Sector: CIMAT Case Study. Lat. Am. Bus. Rev. 2016, 17, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Kayworth, T.R.; Leidner, D.E. An Empirical Examination of the Influence of Organizational Culture on Knowledge Management Practices. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 22, 191–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, S.; Testa, S. Innovation or Imitation? Benchmarking Int. J. 2004, 11, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, L. Why Knowledge Management Is Important to the Success of Your Company. Available online: http://www.forbes.com/sites/lisaquast/2012/08/20/why-knowledge-management-is-important-to-the-success-of-your-company/#54e0b05c5e1d (accessed on 1 January 2015).

- Wiig, K.M. Knowledge Management: An Introduction and Perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 1997, 1, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Innovation Strategy 2015 an Agenda for Policy Action. OECD Rev. Innov. Policy 2015, 395–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popadiuk, S.; Choo, C.W. Innovation and Knowledge Creation: How Are These Concepts Related? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2006, 26, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Gupta, R.K.; Saxena, K.B.C.; Sikdar, A. Knowledge Creation in Organizations: Proposition for a New Model. Knowl. Manag. Innovation Technol. Cult. 2007, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge Creating Company; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, T.H.; Prusak, L. Working Knowledge How Organization Manage What They Know; Harvard Business Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Haslinda, A.; Sarinah, A. A Review of Knowledge Management Models. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2009, 2, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Hislop, D. Knowledge Management in Organizations: A Critical Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Piraquive, F.N.D.; García, V.H.M.; Crespo, R.G. Knowledge Management Model for Project Management. In International Conference on Knowledge Management in Organizations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Handzic, M. Integrated Socio-technical Knowledge Management Model: An Empirical Evaluation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2011, 15, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R. Organizational Change and Information Systems. In Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organisation; Spagnoletti, P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 2, ISBN 978-3-642-37227-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lytras, M.D.; De Pablos, P.O.; Damiani, E.; Avison, D.; Naeve, A.; Horner, D.G. (Eds.) Best Practices for the Knowledge Society. Knowledge, Learning, Development and Technology for All. In Proceedings of the SecondWorld Summit on the Knowledge Society, Chania, Crete, 16–18 September 2009; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zyngier, S.; Burstein, F.; McKay, J. Governance of Strategies to Manage Organizational Knowledge. In Case Studies in Knowledge Management; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2005; pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Stehr, N.; Adolf, M.; Mast, J.L. Knowledge Society, Knowledge-Based Economy, and Innovation. In Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1186–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Rodríguez, A.; Leal-Millán, A.; Roldán-Salgueiro, J.L.; Ortega-Gutiérrez, J. Knowledge Management and the Effectiveness of Innovation Outcomes: The Role of Cultural Barriers. Electron. J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 11, 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Hamel, G.; Mol, M.J. Management Innovation. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2008, 33, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosilj Vukšić, V.; Pejić Bach, M. Background and Scope of the Special Issue on “Innovations Driven by Knowledge Management”. Balt. J. Manag. 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.H.H.; Yip, M.W.; Din, S.b.; Bakar, N.A. Integrated Knowledge Management Strategy: A Preliminary Literature Review. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 57, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, A. Knowledge Management and Innovation at 3M. J. Knowl. Manag. 1998, 2, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, J.; Newell, S.; Scarbrough, H.; Hislop, D. Knowledge Management and Innovation: Networks and Networking. J. Knowl. Manag. 1999, 3, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levett, G.P.; Guenov, M.D. A Methodology for Knowledge Management Implementation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2000, 4, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, M. The Role of Knowledge Management in Innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Rueda, F.; Millot, M. Measuring Design and Its Role in Innovation. 2015. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/5js7p6lj6zq6-en (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. The Five Forces That SHAPE Competitive Strategy; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, S.D.; Johnson, M.W.; Sinfield, J.V. Institutionalizing Innovation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dutrénit, G.; Jover, N. Academia-Sector Productivo: Una Vinculación Fortificadora de Sistemas Nacionales de Innovación. Lecciones de Cuba, Costa Rica y México; Editorial UH: Habana, Cuba, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Diakoulakis, I.E.; Georgopoulos, N.B.; Koulouriotis, D.E.; Emiris, D.M. Towards a Holistic Knowledge Management Model. J. Knowl. Manag. 2004, 8, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrénit, G.; Vera-Cruz, A.O. Repensando el Desarrollo Latinoamericano: Una Discusión Desde los Sistemas de Innovación; Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016; pp. 351–383. [Google Scholar]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Rozakis, S.; Grigoroudis, E. Agri-Science to Agri-Business: The Technology Transfer Dimension. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, S. The Role of Universities in Regional Innovation Ecosystems; Association of European University Presses: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, J.-A. Organisational Innovation as Part of Knowledge Management. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2008, 28, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Choi, H. Knowledge Management Enablers, Processes, and Organizational Performance: An Integrative View and Empirical Examination. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 20, 179–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massingham, P. An Evaluation of Knowledge Management Tools: Part 1—Managing Knowledge Resources. J. Knowl. Manag. 2014, 18, 1075–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, R. Teoría y Diseño Organizacional, 10th ed.; Berrett-Koehler: México, Mexico, 2011; ISBN 978-607-481-764-5. [Google Scholar]

- Perez Lopez-Portillo, H. Knowledge Management and Measurement in Public Sector Organizations; University of Guanajuato: Guanajuato, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Batini, C.; Scannapieco, M. Methodologies for Information Quality Assessment and Improvement. In Data and Information Quality; Data-Centric Systems and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 353–402. ISBN 978-3-319-24106-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, C.H.; Hax, A.C. Manufacturing Strategy: A Methodology and an Illustration. Interfaces 1985, 15, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, R.; Ramsin, R. Methodologies for Developing Knowledge Management Systems: An Evaluation Framework. J. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 19, 682–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pee, L.G.; Kankanhalli, A. Understanding the Drivers, Enablers, and Performance of Knowledge Management in Public Organizations. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Cairo, Egypt, 1–4 December 2008; ACM: Cairo, Egypt, 2008; pp. 439–466. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez López-Portillo, H.; Romero Hidalgo, J.A.; Mora Martínez, E.O. Factores Previos para la Gestión del Conocimiento en la Administración Pública Costarricense. In Administrar lo Público 3; CICAP, Universidad de Costa Rica: San José, Costa Rica, 2016; pp. 102–129. ISBN 978-9968-932-22-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wiig, K.M. Knowledge Management in Public Administration. J. Knowl. Manag. 2002, 6, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-F.; Hsieh, P.-H.; Hung, W.-H. Enablers and Processes for Effective Knowledge Management. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 734–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. United Nations E-Government Survey 2014. “E-Government for the Future We Want”; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Puron-Cid, G. Factors for a Successful Adoption of Budgetary Transparency Innovations: A Questionnaire Report of an Open Government Initiative in Mexico. Gov. Inf. Q. 2014, 31, S49–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.M.; Maxwell, T.A. Information-Sharing in Public Organizations: A Literature Review of Interpersonal, Intra-Organizational and Inter-Organizational Success Factors. Gov. Inf. Q. 2011, 28, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvas, I.; Bassiliades, N. A Process-Oriented Ontology-Based Knowledge Management System for Facilitating Operational Procedures in Public Administration. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 4467–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, K. Information Matters: Government’s Strategy to Build Capability in Managing Its Knowledge and Information Assets. Leg. Inf. Manag. 2010, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Man, A.-P. Knowledge Management and Innovation in Networks; Edward Elgar Publishing: Jottham, UK, 2008; ISBN 9781848443846. [Google Scholar]

- Pisano, G.P. You Need An Innovation Strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 93, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Akhavan, P.; Jafari, M.; Fathian, M. Critical Success Factors of Knowledge Management Systems: A Multi-Case Analysis. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2006, 18, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodgson, M.; Gann, D.; Salter, A. The Management of Technological Innovation: Strategy and Practice, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; ISBN 9780199208531. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.H.; Sriram, R.D. The Role of Standards in Innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2000, 64, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasik, S. A Model of Project Knowledge Management. Proj. Manag. J. 2011, 42, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS; SmartPLS GmbH: Boenningstedt, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).