Social Media in Communicating about Social and Environmental Issues—Non-Financial Reports in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

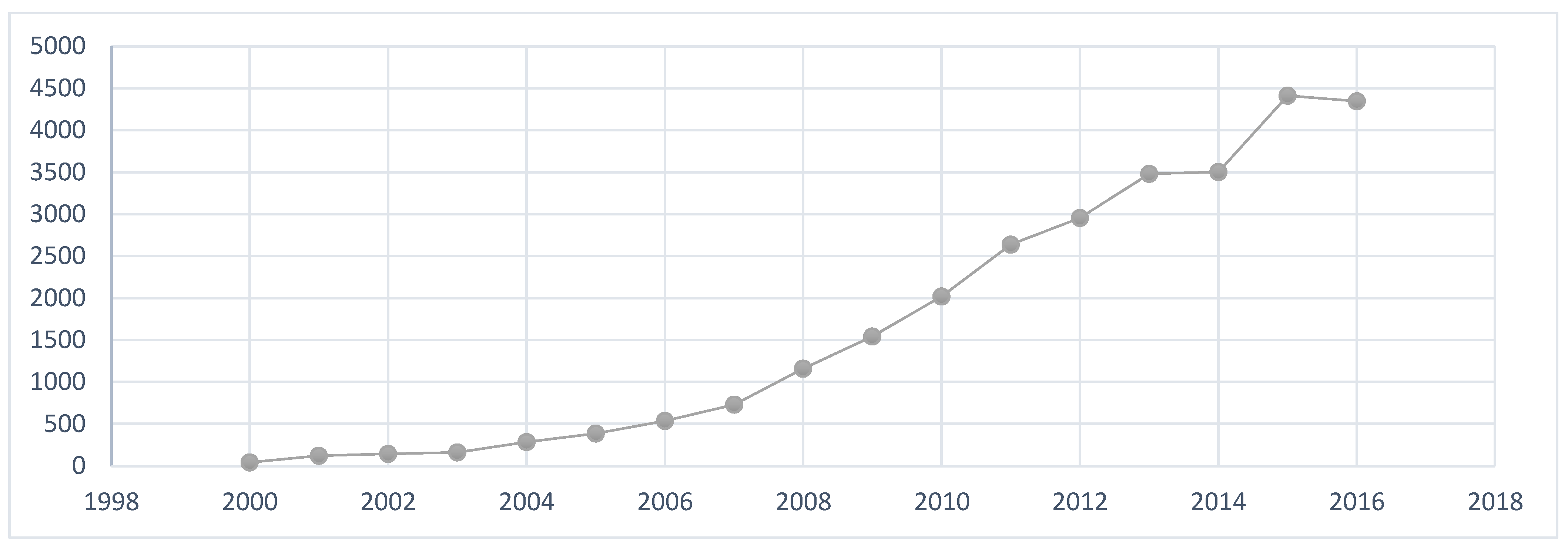

- The analysis covers the number of organizations reporting in the Responsible Business Forum (FOB) reports and their long-term practices and the implementation of socially responsive practices in the long term, in this case related to the analyzed period 2008–2019.

- It was verified which social media platforms entrepreneurs most often use to inform about good practices.

2. Theoretical Background

- -

- what are the costs of CSR activities incurred by the corporation,

- -

- how CSR activities affect the company’s financial results,

- -

- whether the costs related to CSR activities do not exceed the benefits of this activity (for the market, the environment, society).

3. Materials and Methods

4. Communication about Corporate Social Responsibility towards Sustainable Development

4.1. Non-Financial Reporting as a Sign of Growing Importance Stakeholders

4.2. Worldwide Non-Financial Reporting

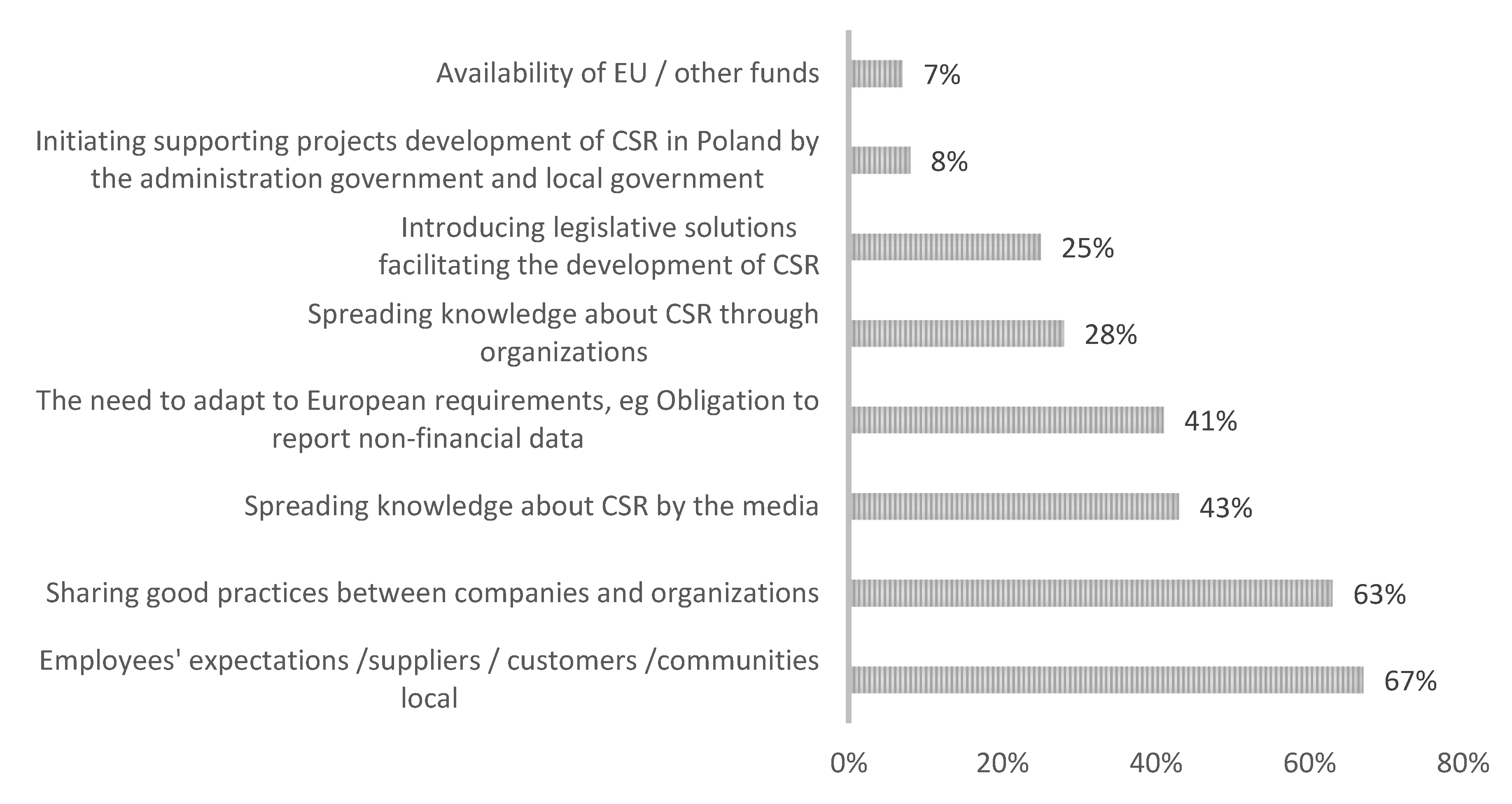

4.3. Social Reporting in Poland

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- A social report should be properly prepared, consistent and credible, in line with a specific communication strategy with the environment, presenting achievements rather than undefined visions of the future, but containing future goals and the manner of their implementation, responses to possible threats, as well as statistical data describing a given organization.

- Periodic social reports have a positive impact on the perception of a given economic organization and improve its competitive position in the market.

- The form of the report and messages on social and environmental activities should be friendly to stakeholders using various computer systems and reading tools. It is recommended to use the information on websites and social forums of enterprises to enable easy data analysis, collecting to track historical changes.

Limitation and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Calcagni, F.; Amorim Maia, A.T.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Langemeyer, J. Digial co-construction of relational values: Understanding the role of social media for sustainability. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1309–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Yalcinkaya, G.; Bstieler, L. Sustainability, Social Media Driven Open Innovation, and New Product Development Performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin, C.J.; Cheng, D.K. Enhancing the performance of supplier involvement in new product development: The enabling roles of social media and firm capabilities. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2018, 23, 462–488. [Google Scholar]

- Cristiano, J.J.; Liker, J.K.; White, C.C. Customer driven product development through quality function deployment in the U.S. and Japan. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2000, 17, 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, A.; Jablonski, M. Social Perspectives in Digital Business Models of Railway Enterprises. Energies 2020, 1, 6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, R. The Changing Nature of Corporate Social Responsibility CSR and Development–The Case of Mauritius; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Menedżerowie CSR 2020 [2020 CSR Managers]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stawicka, E. Sustainable development and the business context of CSR benefits on the polish market. Oeconomia 2017, 16, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliszkiewicz, J. Przywództwo, Zaufanie, Zarządzanie Wiedzą w Innowacyjnych Przedsiebiorstwa [Leadership, Trust, Knowledge Management in Innovative Enterprises]; CeDEWu: Warszawa, Polska, 2019; pp. 1–215. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of Sustainability Reporting: A Review of Results, Trends, Theory, and Opportunities in an Expanding Field of Research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R. Modelling CSR: How managers understand the responsibilities of business towards society. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintrakarn, P.; Jiraporn, P.; Treepongkaruna, S. How do independent directors view corporate social responsibility (CSR) during a stressful time? Evidence from the financial crisis. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 71, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forum Odpowidzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce 2020, [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, C.E.; Rothenberg, S. Firm Performance: The Interactions of Corporate Social Performance with Innovation and Industry Differentiation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. CSR w Polsce Menedżerowie/Menedżerki 500 [CSR in Poland Managers/Managers 500]; GoodBrand & Company: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vashchenko, M. An external perspective on CSR: What matters and what does not? Bus. Ethics 2018, 26, 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluchna, M.; Roszkowska-Menkes, M. Non-Financial Reporting, Conceptual Framework, Regulation and Practice. In Corporate Social Responsibility in Poland; Stehr, C., Przytuła, S., Długopolska, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, B.; Chung, Y. The effects of corporate social responsibility on firm performance: A stakeholder approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joniewicz, T. Szykujcie Dane Niefinansowe [Prepare Non-Financial Data]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lulewicz-Sas, A. Ewaluacja Społecznie Odpowiedzialnej Działalności Przedsiebiorstwa [Evaluation of Socially Responsible Activities of the Enterprise]; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Białostockiej: Białystok, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aureli, S.; Salvatori, F.; Magnaghi, E. A Country-Comparative Analysis of the Transposition of the EU Non-Financial Directive: An Institutional Approach. Acc. Econ. Law 2020, 10, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Directive on Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/non-financial-reporting_en (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce, Dobre Praktyki 2008. [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce, Dobre Praktyki 2009. [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce, Dobre Praktyki 2010. [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce, Dobre Praktyki 2011. [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce, Dobre Praktyki 2012. [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce, Dobre Praktyki 2013. [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce, Dobre Praktyki 2014. [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce, Dobre Praktyki 2015. [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce, Dobre Praktyki 2016. [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce, Dobre Praktyki 2017. [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce, Dobre Praktyki 2018. [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Forum Odpowiedzialnego Biznesu. Raport Odpwiedzialny Biznes w Polsce, Dobre Praktyki 2019. [Responsible Business. Responsible Business in Poland Report, Best Practices]; FOB: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- GRI. Sustainability Disclosure Database. 2018. Available online: http://database.globalreporting.org (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Social Media Users in Poland. Available online: https://napoleoncat.com/stats/social-media-users-in-poland/2019/12 (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Number of Monthly Active Facebook Users Worldwide as of 1st Quarter 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/ (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Kłobukowska, J. Społecznie Odpowiedzialne Inwestowanie na Rynku Kapitałowym w Polsce. Stan i Perspektywy Rozwoju. [Socially Responsible Investing in the Capital Market in Poland. Status and Development Prospects]; Wydawnictwo UMK w: Toruniu, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Michalczuk, G. Raportowanie zintegrowane jako innowacyjne narzędzie rachunkowości w budowaniu relacji inwestorskich. [Integrated reporting as an innovative accounting tool in building investor relations. Studia Ekonomiczne. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach, nr. Studia Ekon. 2016, 299, 222–231. [Google Scholar]

- Churet, C.; Eccles, R.G. Integrated reporting, quality of management and financial performance. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2014, 26, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, D.; Brash, C. Management customer relationships in the e-business world: How to personalize computer relationships for increased profitability. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2001, 29, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawicka, E. Sustainable Development the Digital Age of Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, G.; Apostolakou, A. Corporate social responsibility in Western Europe: An institutional mirror or substitute? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, S.J. Using social media to discover public values, interests, and perceptions about cattle grazing on park lands. Environ. Manag. 2014, 53, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCI France Pologne. CSR w Praktyce. Barometr francusko-polskiej Izby Gospodarczej. [CSR in Practice. Barometer of the French-Polish Chamber of Commerce]; CSR w Praktyce: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aluchna, M.; Anam, L.; Joniewicz, T.; Sowińska, E.; Stachniak, A. Brak raportowania przestanie się opłacać. Rzeczpospolita 2021, A13, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst & Young LLP. Value of sustainability reporting. In A study by EY and Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship; Ernst & Young LLP: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- EU. Komisja Europejska. Wytyczne Dotyczące Sprawozdawczości w Zakresie Informacji Niefinansowych, 2017/C 215/01. 2017. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52017XC0705(01)&from=PL (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Kotonen, U. Formal Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting in Finnis Listed Companies. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2009, 10, 176–207. [Google Scholar]

- Aboujaoude, E. The virtual personality of our time. The dark side of e-personalities. In Wirtualna Osobowość Naszych Czasów. Mroczna Strona E-Osobowości; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, C.A.; Patti, V. Editorial for the Special Issue on “Love & Hate in the Time of Social Media and Social Networks”. Information 2018, 9, 185. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Feijoo, B.; Romero, S.; Ruiz, S. Effect of Stakeholders’ Pressure on Transparency of Sustainability Reports within the GRI Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, D. Do Financial Markets Care About Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure? Further Evidence from China. Aust. Account. Rev. 2017, 34, 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, S.; Stawinoga, M.; Velte, P. Stakeholder expectations on CSR management and current regulatory developments in Europe and Germany. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2015, 12, 505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Lament, M. Quality of non-financial information reported by financial institutions. The example of Poland and Greece. Cent. Eur. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2017, 22, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Tiron-Tudor, A.; Nicolò, G.; Zanellato, G. Ensuring more sustainable reporting in Europe using non-financial disclosure–De facto and de jure evidence. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. The corporate governance reporting in the European Union. In Driving Productivity in Uncertain and Challenging Times; Cooper, C., Ed.; University of the West of England, British Academy of Management: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peršić, M.; Janković, S.; Krivačić, D. Sustainability accounting: Upgrading corporate social responsibility. In The Dynamics of Corporate Social Responsibility; Aluchna, M., Idowu, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 285–303. [Google Scholar]

- Venturelli, A.; Caputo, F.; Cosma, S.; Leopizzi, R.; Pizzi, S. Directive 2014/95/EU: Are Italian companies already compliant? Sustainability 2017, 9, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, M.; Sabelfeld, S.; Blomkvist, M.; Tarquinio, L.; Dumay, J. Harmonising non-financial reporting regulation in Europe: Practical forces and projections for future research. Meditari Account. Res. 2018, 26, 598–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, C.; Rocca, L.; Veneziani, M.; Teodori, C. Ex-ante impact assessment of sustainability information–the Directive 2014/95. Sustainability 2014, 10, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, J.; Riedl, E.J.; Serafeim, G. Market reaction to mandatory nonfinancial disclosure. Manag. Sci. 2018, 65, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- CSRinfp. Raporty Społeczne, Ranking [Social Reports, Ranking]. CSRinfo. Available online: https://www.csrinfo.org/ (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Werenowska, A.; Rzepka, M. The Role of Social Media in Generation Y Travel Decision-Making Process (Case Study in Poland). Information 2020, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefănescu, C.A.; Tiron-Tudor, A.; Moise, E.M. Eu non-financial reporting research–insights, gaps, patterns and future agenda. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2021, 22, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litz, R.A. A resource-based-view of the socially responsible firms: Stakeholder interdependence, ethical awareness, and issue responsiveness as strategic assets. J. Bus. Ethics 1996, 15, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Henriques, I. Stakeholder influences on sustainability practices in the Canadian forest products industry. Strateg.Manag. J. 2005, 26, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L. Stakeholder influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 794–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Dmytriyev, S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Stakeholder Theory: Learning from each other. Symph. Emerg. Issues Manag. 2017, 1, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Rosati, F.; Venturelli, A. The determinants of business contribution to the 2030 Agenda: Introducing the SDG Reporting Score. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zicari, A. Can One Report be Reached? The Challenge of Integrating Different Perspectives on Corporate Performance. In Communicating Corporate Social Responsibility: Perspectives and Practice; Tench, R., Sun, W., Jones, B., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; pp. 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P.; Song, H.-C. Similar but not the same: Differentiating corporate sustainability from corporate responsibility. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 105–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, M.; Adams, M.; Walker, T.R.; Magnan, G. How corporate social responsibility can be integrated into corporate sustainability: A theoretical review of their relationships. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 25, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stawicka, E.; Paliszkiewicz, J. Social Media in Communicating about Social and Environmental Issues—Non-Financial Reports in Poland. Information 2021, 12, 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12060220

Stawicka E, Paliszkiewicz J. Social Media in Communicating about Social and Environmental Issues—Non-Financial Reports in Poland. Information. 2021; 12(6):220. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12060220

Chicago/Turabian StyleStawicka, Ewa, and Joanna Paliszkiewicz. 2021. "Social Media in Communicating about Social and Environmental Issues—Non-Financial Reports in Poland" Information 12, no. 6: 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12060220

APA StyleStawicka, E., & Paliszkiewicz, J. (2021). Social Media in Communicating about Social and Environmental Issues—Non-Financial Reports in Poland. Information, 12(6), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12060220