Abstract

As a country, Romania tries to communicate abroad its authenticity, intact nature and unique cultural heritage. This message matches perfectly the main attributes associated to Rodna Mountains National Park, as it is the second national park in Romanian. The aim of the research is to identify and analyze the prospects for sustainable development of rural tourism in the area of Rodna Mountains National Park, taking into account its impact on the social and economic life of the inhabitants of the Rodna commune, but also factors that may positively or negatively influence the whole process. From a methodological perspective, quantitative methods were used; a survey-based research was carried out among Romanian mountain tourists, aiming at identifying and analyzing their opinions and suggestions regarding tourism in protected areas in Romania, as well as the impact of the tourist flows generated by the Park upon the surrounding communities. Rodna Mountains National Park seems to be among the favorite destinations of tourists, as the respondents have a good and very good general impression about the interaction with the mountain and protected areas, prefer internal to external destinations regardless of the season, budgets allocated per night, per stay and annually are quite high, so the purchasing power is also high; they constitute a solid foundation for the decisions of the tourist development of the area. The need for holidays and the savings that tourists make throughout the year to go on vacation, regardless of income level, give viability to this opportunity. Other results of this research are related to the problems tourists helped to identify and the solutions they proposed.

1. Introduction

Most research studies targeting Romania’s foreign visitors originating from the country’s identified target markets, with the purpose of better understanding the reasons why they pick Romania’s destinations, have led to the identification of the key attributes of the national tourist brand Explore the Carpathian Garden!: intact nature; authenticity; unique culture; and safety. Furthermore, researchers concluded that the brand’s personality must focus on features like good, pure, green, and innocent, and when emphasizing the values of the tourist brand: exploration, spirituality, and good and simple life. Thus, the differentiation elements of Romania as opposed to other destinations are linked to the intact nature, the unique cultural heritage, and the authentic rural lifestyle. In fact, these elements constitute the six forms of tourism to be promoted and developed by Romania during the coming years with priority: tourist circuits, rural tourism, virgin nature and natural parks, health and beauty tourism, active and adventure tourism, and city-breaks. Briefly, authorities try to communicate abroad that Romania “is an authentic country, with intact nature and with a unique cultural heritage”. This message matches perfectly the main attributes associated with the destination by foreign tourists who have visited the destination or who know persons who have visited it: authentic, rural, hospitality and green [1,2,3].

On one hand, taking into consideration the differentiation elements of Romania as a destination, and on the other hand bearing in mind the very many challenges faced by rural communities in Romania, it becomes obvious that rural tourism is one of the most effective solutions for harmonizing environmental conservation requirements and norms, of increasing sustainability and of providing significant development solutions for vulnerable destinations [4]. Regarding the development of sustainable tourism, Cucculelli and Goffi [5] state in their paper that, although there is no exact definition in the literature, because each destination has its specific attributes, we know that this development of sustainable tourism is a long term objective and a dynamic, ever-changing concept. The objectives of this development are to minimize the negative effects on the environment, to protect the cultural heritage and at the same time to provide learning opportunities, including positive benefits for the local economy and contribution to increasing the structure of local communities. In a broader sense, rural tourism refers to holidays in rural areas, but this definition seems to be quite inaccurate, generating divergent views on the content and characteristics of rural tourism. If rural tourism is a wider concept, the agritourism is more rigid, respecting a series of regulations. According to the UNWTO [4,6], agritourism refers to staying in someone’s house (boarding house, farm), consuming agricultural products from the locals, and participating in all the specific agricultural activities. A definition of agritourism is stated by Stănciulescu, Lupu, Țigu, Titan, & Stăncioiu [7]: “Agritourism represents a form of tourism, which is practiced in the rural environment, based on providing, under peasant household conditions, services such: accommodation, meal, entertainment and others. Thus, through agritourism, the natural and anthropic resources of the area are capitalized in this way, contributing to raising the standard of living of the rural population. Unlike rural tourism, agritourism involves accommodation in the peasant household (pension, etc.); the consumption of agricultural products from the household; participation to some extent in the activity required for agriculture”.

Jugănaru, Jugănaru, & Anghel (2008) highlight the fact that the generous characteristics of sustainable tourism allow it to take various forms, such as ecological tourism, green tourism (ecotourism), light tourism (soft tourism), rural tourism and agrotourism, community-based tourism, fair, solidarity and responsible tourism, etc. [8].

From among these, we consider that community-based tourism is one of the most appropriate forms for the development of tourism in the villages surrounding the Rodna Mountains. Community-based tourism refers to the involvement of locals in the development of tourism for their benefit: they build and manage accommodation units, as well as local services offered to tourists. Increased attention is paid to respecting the nature and traditions of the local population, which are in fact the real added value. Community-based tourism contributes significantly to the development of production activities, such as those related to agricultural products or handicraft workshops, the products of which are sold mainly to tourists. Connell (1997) states that participation is “not only about achieving a more efficient and equitable distribution of material resources: it is also about exchanging knowledge and transforming the learning process itself into a service for the development of people’s self” [9]. This definition brings the collaboration between those involved in tourism activities within the commune under scrutiny. In this regard, Bramwell et. all (2016) noted that locals need to be encouraged to move towards a sustainable approach to tourism development: if tourism is a revenue-generating sector for local communities and can have a multiplier effect, then the host population must feel empowered, fully participating in development [10]. Therefore, in order to achieve a convergence between different types of tourism and sustainable tourism, there is a need for proper demand management and especially awareness among locals about the benefits of such an approach and the creation of an enabling environment in which they can actively and freely participate in a sustainable development of tourism in the area.

At the same time, rural tourism also plays an important role in the green economy. Mukhambetova, et al. (2019) define this concept as being “a system of economic activities related to the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services that lead to increased human well-being on the long run, while not exposing future generations to significant environmental risks or environmental deficits” [11]. Practically, the definition relies on the concept of sustainability: maximizing the benefits, while minimizing the negative impacts.

Like in other Eastern European countries, Romanian mountain tourism has registered a rapid development beginning with the 1990s. In fact, the increasing popularity of mountain destinations, in the context of a lax legal framework, led to an unbalanced development of the supply side, as Tănase & Nicodim (2020) point out [12]: “These resulted in concentration of the offer in certain areas and buildings with a questionable framing from the legal point of view. Without taking into account the accommodation capacity of the destination or the access roads, we are now in the situation in which there is overcrowding, especially during weekends and during the tourist seasons”. The same authors, Tănase & Nicodim (2020), also highlight the main conclusions of the 9th World Congress on Snow and Mountain Tourism (UNWTO, 2016), according to which, overall, today’s tourists present an increased interest for sport and adventure tourism and, at the same time they are also more and more interested in health tourism. Furthermore, tourism is closely linked to creating special moments and to generating emotional experiences. Gaining popularity, adventure tourism is becoming “softer” and it increases the chances of revenues to stay in the visited destination. Moreover, authenticity is achieved by linking tourism to the local culture and local people. At the same time, the need for a balanced development taking economic needs and nature protection into consideration also increases. Of course, the role of digitalization is also emphasized, as it is closely linked to the tourists’ decision-taking process in terms of destination choice, providing them access to information but also personalization possibilities and mobile experiences. Furthermore, mountainous destinations gain popularity in the context of the new global trends that encourage hiking tourism and raise the younger generations’ interest towards such activities [12,13].

Mountain tourism is also strongly related to the respect for nature. Duglio & Letey (2019) say that “together with the main aim of preserving nature, national parks are also expected to play an important role for the local communities, driving economic activities toward the lens of sustainable development” [14]. According to Dinică (2017) [15], the demand for protected area tourism is growing, raising concerns for its environmental sustainability. At the same time, sustainability can be the key for the development of tourism in protected areas, by bringing together hiking tourism and cultural experiences [13]. Butzmann & Job (2016) [16] add that only an appropriate mix of tourism products in protected areas can help fulfill the double mandate of both “protection” and “use”, which are demanded by the political, socio-economic and environmental changes. A study carried out by Dumitraș et al. (2017) [17] in which an on-site survey questionnaire was presented to visitors of national and natural parks in Romania showed that tourists gain benefits after visiting the protected areas, which assures their “use”, but not their “protection”.

The local community is a key actor in sustainable tourism. Souca (2019) ran a research, focusing on the rural communities in Romania. She concludes that Romanian villages have not achieved their full potential offering in terms of rural tourism, because of the poor involvement of the local community in the strategic tourism planning process, and because of the changes in the tourists’ behaviour. In urban areas, in response to these changes in the tourists’ behaviour, a better form of cultural tourism has emerged, namely creative tourism. The study showed that not only the urban areas, but also the Romanian rural areas have residents endowed with abilities necessary in developing creative tourism. The main conclusion was that to revitalize the Romanian rural tourism, the entire local community needs to be involved in the tourism planning process, not just the ones with direct ties to it [18].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Area of Investigation

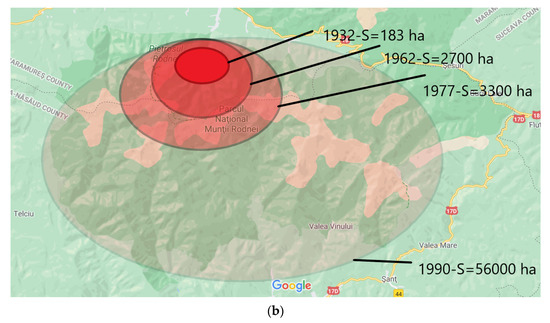

Rodna Mountains National Park (RMNP) is the second national park in Romania. Its protection began in 1932 with the recognition as a scientific reserve of the 183 hectares (ha) of alpine pit in the Pietrosu Mare peak (in fact, the country’s first such reservation). The reserve expanded to 2700 ha in 1962, growing later to 3300 ha, in 1977. The protected area was awarded the most important status in Paris, in 1979, when the 3300 ha were declared by the United Nations Educational Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO) as an area of the Biosphere Reserve under the Human and Biosphere Program. Obviously, “being part of the World Heritage is considered an honor and nations lobby hard to get their buildings and historic ruins on the list, a stamp of approval that brings prestige, tourist income, public awareness, and, of most importance, a commitment to save irreplaceable monuments” [19]. Afterwards, the pastures and forests of the Rodnei Mountains, a rich resource of biodiversity, have been centralized and the Park has grown continuously (Figure 1). Furthermore, researchers and specialists from the Biological Research Institute of Cluj and Bucharest drew up the Fundamental Study between 1980 and 1985, which was later approved by the central public authority responsible for the environment. This was the last stage that led to the establishment of the Rodna Mountains National Park, a protected natural area, with the status of a national park, “for the preservation of biodiversity and landscape, protection of rare and valuable species, for the promotion of and encouraging tourism, awareness and education of the public in the spirit of nature protection and its values, with a total area of 46,399 hectares, being the second largest in the category of national parks in the country” [20,21,22,23].

Figure 1.

(a) The Location of the Rodna Mountains National Park. (b) The Development of the Rodna Mountains National Park. Source: [24].

As recognition of its international value, in 2007, the park became a Natura 2000 site (SCI–Site of Community Importance and SPA–Site of Avifaunistic Importance), covering today a total area of 47,500 ha (the park extended to the East, including the Gagi glacier, with an area of 1101 ha) [20]. Thus, Rodna Mountains National Park is an important protected area that contributes to the preservation of the Carpathian biodiversity, a valuable resource both at European and global levels, as proven by the Carpathian Convention, signed in 2007. The Convention includes Romania, together with the other six Carpathian countries (The Czech Republic, Poland, Serbia, Slovakia, Ukraine and Hungary). This partnership aims at facilitating the collaboration between governmental and non-governmental organizations, specialized institutes, international experts and financiers. The goal of the partnership is, of course, to protect the Carpathian biodiversity and to facilitate the area’s sustainable development.

RMNP includes only part of the whole Rodna Mountains chain, namely from West to East, a length of the main ridge of about 55 km (km) (from Şetref-pass to Rotunda-pass) and from North to South, a length of 25 km (from Prislop-pass to Valea Vinului village in Rodna commune). Approximately 80% of the park’s surface is located in Bistrița-Năsăud County and the remaining 20% is located in Maramureș County. Visitors can access the park by train only via the Salva-Vișeu railway line, after the closure of the Ilva Mică-Rodna railway line in 2017, which used to provide several access routes to the park. Access is also provided by the roads connecting Transylvania to Maramureș (via Şetref-pass on DN17C) and Moldova (through Rotunda-pass, on DN17D, currently undergoing rehabilitation works).

As of May 2004, the Administration of the Rodna Mountains National Park (ARMNP) is the management body of the park (according to the Management Contract No 734/22 May 2004). Having financing and management attributions, ARMNP is headquartered in Rodna commune, Bistrița-Năsăud County; a working point has been set up in Borșa, Maramureș County. The objectives of the managing body include: the implementation of the actions foreseen by the management plan; to draw up project proposals; to access various sources of financing; to start attractive tourist programs; to generate revenues for the RMNP and the neighboring local communities; to develop tourist facilities (retreats, refuges, halting points, parking lots, information boards, etc.) and to ensure the maintenance and renovation of the existing tourist facilities; to carry out scientific and various volunteer activities within the park; to map the habitats and species of community interest, by digitizing satellite images or aerial photography of the RMNP area and by verifying them in the field; to calculate the population optimum for a number of key species of flora and fauna, compulsory steps for the inclusion of RMNP in international networks that promote ecological tourism and the harmonious communion of human beings with nature (PAN-Park, MAB-UNESCO); the establishment of management lines for a number of priority conservation habitats; the exchange of experience with other similar protected areas in the country and abroad and the development of an adequate infrastructure for RMNP, by setting up sightseeing centers, information points, mountain trails, offering visitors and tourists the opportunity to enjoy information and safety during the visit of the park [20].

Obviously, the top management of the ARMNP sees tourism as a valuable income source and high potential for the locals in the areas adjacent to the park. Furthermore, the interest in sustainable, ecological tourism is also visible, as the park authorities want to be actively involved in various international specific networks, such as the MAB UNESCO committee, and programs, such as “IMPACT Innovative models for protected areas—exchange and transfer” financed through the INTERREG program between 2016 and 2020. Since 2014, the average yearly number of park visitors has exceeded 30,000 tourists, with more than two thirds of them arriving during the peak season (July and August); some 75% access the park from the North, while only the remaining 25% enter from the Southern side. Visitors can choose from 19 available visiting routes, amounting 374 km of marked and signalized trails and 14 halting places [25]. Compared to the most popular worldwide protected areas, which record tourist arrivals of millions and even tens of millions, the number of yearly arrivals is very low [26]. The arrivals indicator per square kilometer (km2) registers a very small value (of 0.0256 tourists/km2/year), allowing further development within the limits imposed by the principles of sustainability. In addition, according to the National Institute of Statistics (NIS) [27], tourist arrivals amount in Rodna to a little more than 1000 tourists per year (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tourist activity in the Rodna commune.

The values of the average length indicator are low and suggest transit or business tourism. Still, given the low development of local businesses and the fact that the destination is located rather at an end of the road, the calculated values reflect a low attractiveness of the commune’s tourist offer and a poor capitalization of the tourist potential of the park. However, perhaps partly due to the recent national promotion of tourism and partly due to some local actions, the current trend is on the rise, which once again confirms the tourist potential of the destination.

2.2. Methodology

This research study is part of a larger one, conducted by the authors between the years 2017 and 2018, with the purpose of identifying and analyzing the prospects of sustainable rural tourism development in the Rodna Mountains National Park area. From a methodological perspective, this research paper relies on the usage of quantitative methods. A survey-based research has been carried out among Romanian mountain tourists, that may or may not have visited Rodna Mountain National Park, aimed at identifying and analyzing their opinions and suggestions regarding tourism in protected areas in Romania, concentrating on the Rodna Mountains National Park, as well as the impact of the tourist flows upon the neighboring communities. A self-applied questionnaire was designed, tested and launched online in 2017 via various communication channels, social-media platforms (mostly on Facebook), Romanian online forums, and discussion groups; printed versions of the same questionnaire were distributed to the park’s visitors by the ARMNP. As a tool of quantitative research, the self-applied online questionnaire allows relatively easy contact with mountain tourism practitioners and involves considerable timesaving in the processing of results. The analysis of the data was carried out with the support of a specialized software package, namely, using IBM SPSS Statistics. The survey consisted of 25 questions related to mountain tourism and 7 questions related to identification data of the respondents. A total number of 131 valid responses were received, from a total of 131. Approximately 2700 mountain tourists received the questionnaire. These tourists were targeted online, being selected from various discussion groups and platforms dedicated to mountain tourism in Romania. It can be seen that, from a demographic point of view, the structuring of respondents is appropriate. In terms of gender, the two sexes are evenly distributed. In fact, the same is overall valid for the members of the targeted groups. Age groups are also balanced, with a somewhat higher representation of the 19- to 45-year-old persons, followed by the 46 to 55 and 56–65 age groups; these groups are consistent, as well, with the profile of the Romanian internet users. Most respondents do not have any children (70.22%). Furthermore, in order to be able to consider the sample representative from the point of view of the respondents’ occupational status, the division between the large categories must be relatively balanced. This is also the case for the sample in question, which largely respects the proportions at national level. Likewise, the income distribution also reveals an evenly split sample.

Induction and deduction contributed considerably to the interpretation of the current situation of the disadvantaged communities and to the identification of the possible future situation if the tourist offer would develop both quantitatively and qualitatively. They are mostly used for combining quantitative research, based on the online questionnaire and correlating certain factors identified after analyzing the answers, with qualitative, focused on face-to-face interviews conducted in 2017 with three economic and social categories: entrepreneurs (6 out of a total of 7 accommodation unit owners existent in the Rodna commune in 2017; 2 agro-tourism boarding houses; and 4 rural boarding houses), exponents of public administration (Rodna commune City Hall and Rodna Mountains Park Administration) and locals.

Furthermore, for an analysis as complex as possible and with results as close as possible to reality, it is necessary to test the bivariate correlations based on different answers in order to identify whether or not there is a significant link between the various variables analyzed. The IBM SPSS Statistics Data Editor program was used in this respect. Given the relatively low number of responses received, the authors decided not to run any other statistical test, considering that their relevance would be affected by the sample-size.

3. Results and Discussions

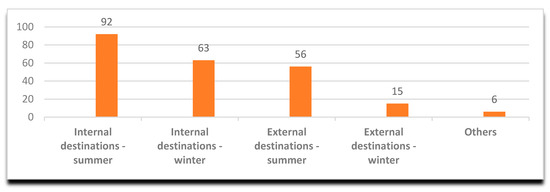

Romanian tourists mainly opt for domestic destinations (Chart 1) during the warm season (92 of 131), followed by domestic, national destinations in the cold season (63), respectively by the external, foreign destinations during the summer season (56) and in the cold one (15). Other choices may include a lack of preference for one season or for the destination type.

Chart 1.

Destination preference, by type.

The preference of tourists for domestic voyages and for summer trips is obvious. In terms of choice frequency, of different types of destinations, there is a clear preference for mountain destinations in the summer (with an average score of 1.92 on a scale of 1–always to 4–never) followed by mountain destinations during winter (2.35), sea (2.56), city-break (2.85) and spa resorts (3.16).

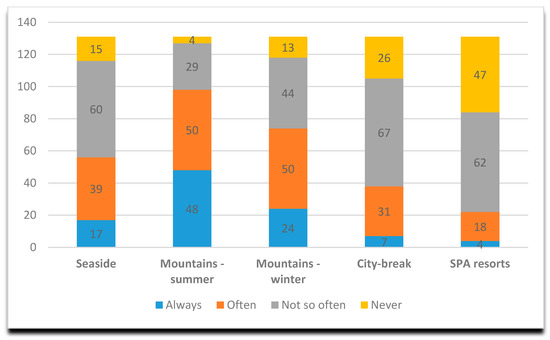

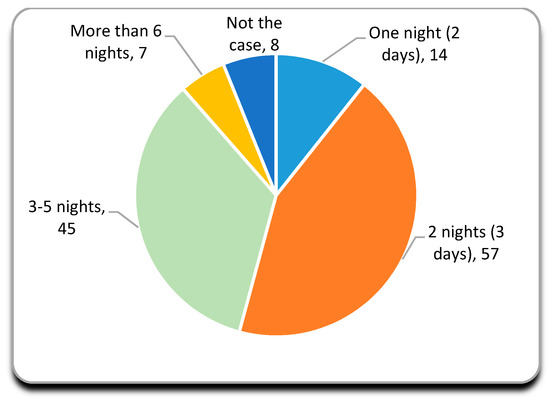

Thus, Romanian respondents generally prefer (Chart 2) domestic mountain destinations during the summer. Furthermore, the same respondents choose internal mountain destinations at least once a year, while the mountain destinations from abroad only once in 5 years or never. Typically, the average length of stay (Chart 3) in the case of such holidays is of 2 to 5 nights; 44% of the respondents seem to prefer short weekend breaks (of two nights), while a little more than a third spend 3 to 5 nights on such trips (34%).

Chart 2.

Frequency of destination choice, by type.

Chart 3.

The average length of a holiday in the Romanian mountains.

In order to establish whether tourists consciously or not pick National and/or Natural Parks, they were asked to mention how often they take into considerations such protected areas as mountain holiday destinations. The responses lead to the finding that the proximity of the destination to such an area is not a conscious decision criterion. Furthermore, tourists were asked how many of their holidays in the last 5 years were in protected areas. The answers indicate, on average, 4.6 holidays in protected areas. Thus, one may conclude that Romanian tourists do not necessarily consciously choose such types of destinations but these destinations are included in the list of frequented areas. The respondents were asked to spontaneously mention protected areas; thus, the most famous ones among them are: Retezat National Park, Rodna Mountains National Park and Piatra Craiului National Park. These responses confirm that Rodna Mountains National Park is one of the most well-known protected areas in Romania. When asked to mention their preferred hiking destinations, the respondents named: Rodna Mountains, Apuseni Mountains and Retezat Mountains. Once again Rodna Mountains enjoy popularity and also a visible preference of the tourists. Therefore, its increased tourist potential is highlighted. Moreover, Rodna Mountains National Park ranks first in terms of tourists’ preferences, being followed by Retezat and Apuseni.

When tourists opt for holidays in protected areas, the main reasons for choosing this type of destination are: hiking, curiosity related to certain tourist attractions, environmental quality and enriching knowledge by observing some plants or animals. By correlating the answers provided by the tourists with the suggestions of the entrepreneurs for the local public authorities related to how to increase the number of tourist arrivals in the area [28], one may point out that it is compulsory to mark tourist routes properly and to produce quality tourist maps, revealing that tourists are first of all concerned with their safety when picking mountain destinations.

The research also focused on establishing why tourists opted in the past (more than 5 years ago) for the Natural and/or National Parks they had visited. Thus, the main reasons indicated for visiting such areas are represented by (well-preserved) nature and its special landscapes, while those who did not opt for such destinations mentioned the lack of interest as main reason. For a better evaluation of the attractiveness of Natural and/or National Parks, tourists were asked to mention the sources of their dissatisfaction; the main aspects are presented in decreasing order: tourist pollution, followed by the lack of tourist marking signs, and the management and marketing of the park, especially in the field of promotion, whereas tourists consider that there is a need for more intensive and efficient promotion of these areas. Once the main issues were mentioned, tourists also came up with solutions for the improvement of the identified problems. Thus, they largely agree that the management of protected areas needs to be improved, and to a lesser extent, tourists propose more intensive promotion, the improvement of the tourist offer, the improvement of the access infrastructure, and the implementation of measures and actions to empower and educate tourists. Until now, the need for proper marking signs on tourist trails, more intensive promotion of protected areas, and the improvement of the access infrastructure were mentioned by the entrepreneurs and the locals during the interviews [28] and were also brought up by the respondents of the questionnaire. However, the education and responsibility of tourists have not been discussed so far. Thus, in order to observe the civic responsibility of the tourists, they were asked if they took part in one of the most extensive waste collection programs run in the forests, namely “Let’s do it, Romania!”. Both affirmative and negative answers needed explanations. The results show that the vast majority of respondents (70.22%) did not participate due to the program’s poor promotion and low recognition (“I do not know the program”) and to the lack of free time (busy schedule). However, among the reasons for participation, the tourists mentioned the desire to actively participate in changing the world into a better place and also to reduce the level of illegal garbage disposal and pollution.

Furthermore, tourists were asked about the activities they opt for during a mountain holiday. The responses were varied enough, including among their preferences: hiking, tourist orientation, barbeque and downhill slope-based skiing. These results are in line with the conclusions of interviews taken with the entrepreneurs and the park administration, which identify mountain hiking as an activity preferred by the large majority of tourists [28].

Mountain tourism is clearly one of the types of tourism carried out in groups. Thus, tourists were asked to mention how many people accompany them while mountain hiking; in this respect, it has been found that the groups of tourists generally consist of two to four persons and rarely exceed six people.

Moreover, related to the form of the group preferred by tourists for mountain hiking (Chart 4), not in terms of size, but as composition, the answers indicated a reluctance to travel to such destinations with children, parents, and other relatives; most of the tourists chose to be accompanied by friends. Obviously, this situation is also consistent with the fact that most respondents do not have children at all. On the other hand, the age of children influences the behaviour of tourists: a holiday with a child less than 2 years of age will be different from many points of view compared to a holiday with a 5–10-year-old child and even more different than a holiday with or without a child over 18 years old. The respondents with all-grown children are quite numerous. Furthermore, investigating whether these groups of tourists call for guiding services or not, it seems that the frequency with which tourists benefit from specialized guidance is very low: nearly 55% of the respondents never ask for such services and another almost 37% seldom consider such services. This situation does not necessarily indicate an educated consumer, nor is it consistent with the aforementioned safety-first concern.

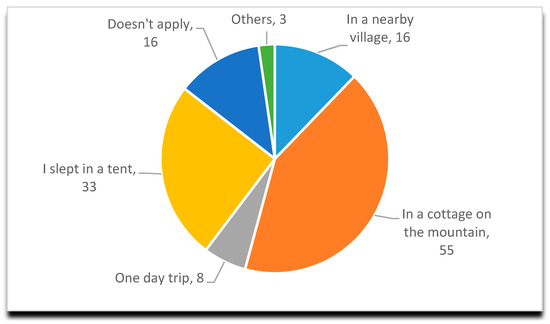

Chart 4.

The types of accommodation establishments chosen by tourists who go on hiking trips.

Related to the preferred types of accommodation units, the results show mountain cottages on the top of the list, followed by tents and accommodation units in the nearby villages (Chart 4). One may deduce that tourists prefer hiking for more than one day and, consequently prefer not to return to the neighboring villages, but this does not exclude the possibility for tourists to accommodate in a nearby locality before and after the hiking in order to rest.

Of course, depending on the types of trails, in certain destinations tourists will not spend more than a night in one cottage. Another explanation for the fact that tourists do not choose in large numbers to stay in the nearby villages is also related to the fact that some of them live in the proximity of the protected areas. When asked how often they visit Natural and/or National Parks in the case they live nearby, the visiting frequency is quite high.

The financial aspect was also approached. Thus, the answers provided by the tourists led to an average budget for one night (2 days) of 294.08 lei (approx. 60 euros), an average budget for the whole stay of 935.64 lei (approx. 190 euros), and an average annual budget for holidays of 4783.60 lei (approx. 982 euros).

In order to be able to conclude on how tourists relate to protected areas, they were asked about their general impression relative to their past interaction with the mountain and with the protected areas. Thus, many tourists have a good and very good impression both in terms of interaction with the mountain and also with the protected areas.

For a more complex and realistic analysis bivariate correlations were tested based on the provided answers, aiming at establishing whether or not there is a significant relation between the analyzed variables, taking into consideration a level of significance of 0.05. A specialized software solution was used in this respect. The main findings relative to the tested variables are briefly presented below.

As data presented in Table 2 reveal, a significant, positive, strong relationship was identified between those who choose mountain destinations during the summer and those who choose mountain homeland destinations.

Table 2.

Strong, positive connection between those who choose mountain destinations during the summer and those who choose mountain destinations in Romania.

Thus, those who choose mountain destinations prefer the ones in the country. The same was tested for those who choose mountain destinations in the winter.

The link between them and those who prefer domestic mountain destinations is positive (Table 3) but of medium intensity. This reveals that summer mountain tourism is preferred in the country, while winter tourism is in close competition against foreign destinations.

Table 3.

Average, positive connection between those who choose mountain destinations in winter and those who choose mountain destinations in their homeland.

The existence of a link between the average duration of a holiday in the country and the budget allocated for a stay was also analyzed, resulting in a positive, medium-intensity link (Table 4). This is due to transport costs that apply irrespective of duration and some potential discounts for long-term accommodation. The longer a holiday will be, the larger the budget for the entire stay.

Table 4.

Positive link, of medium intensity, between the duration of a holiday in the country and the allotted budget per stay.

Another test shows that there is no significant link between the average length of a holiday in the country and the monthly income per person of the respondents.

Thus, when tourists plan their vacation time, this is not influenced by their income levels (Table 5). Tests also show that there is no relationship between the chosen park and the budgets allocated per night (−0.21), throughout the stay (−0.15) and annually (0.10), neither between the preferred park and the monthly income (0.02) per person, which means that holidays in different protected areas do not involve different levels of budgets or incomes, holidays of this type having the same overall costs, irrespective of the protected area that represents the destination. There is no link between the tourists’ favorite park and the impression they have related to protected areas (0.08); generally, tourists perceive protected areas as good and very good. Furthermore, there is no link between the preferred park and the frequency with which tourists spend their holidays in protected areas near their home (0.00). This leads to the conclusion that the preference for certain protected areas is related to popularity and to the way those responsible for managing the area promote the specific destination. The number of holidays in the protected areas of the last 5 years and the monthly income per person are not linked (0.11), respective of the annual budget allocated for holidays (−0.11). The choice of holidays in protected areas is not influenced by income or holiday budget. Consequently, not only tourists who do not have large incomes and cannot afford their holidays in exotic destinations opt for this type of destination, but also those who have large incomes and want to relax, reconnect with nature, breathing clean air and disconnecting from everyday activities and concerns. Taking these findings into consideration, types of accommodation and travel services can be varied, addressing more customer segments.

Table 5.

Lack of a link between the average length of holiday in the country and the monthly income per person of the respondents.

A strong positive link (0.55) exists between those who choose to spend their holidays in protected areas with children and the number of children in a family. Thus, families with children choose to spend their holidays with their little ones. An average-intensity relationship (0.24) exists between those who choose to spend their holidays with children in protected areas and the type of accommodation unit chosen, meaning that tourists traveling with children often prefer other types of compared to those who travel without children, most of the time choosing accommodation in the nearby village.

It is obvious that there is a strong positive link between the budget for a night (2 days) and the budget for the entire stay (0.69), but not between the budget allocated for a stay and the monthly income per person (0.18). Thus, it can be deduced that the need for holidays and relaxation exists regardless of the person’s income, and tourists raise money for holidays regardless of their income levels.

The relatively small number of respondents brings some limitations to the research, the results being representative for the investigated sample but they may differ in the case of other samples and other contexts. This is due to the very low rate of responses to online surveys that do not allow adequately stratify the population, as is the case with public opinion surveys.

Results can be summarized by pointing out the problems they helped identify, the solutions they proposed, but also the motivating factors for holidays in protected areas, and some of the tourists’ characteristics. Therefore, tourists report an issue of major importance in nature protection, namely the problem of waste, as observed by the majority of the respondents. However, their level of involvement in solving this problem is very low, inferred from the very low interest towards the participation in events such as “Let’s do it, Romania”. It is, therefore, the issue of the clandestine passenger: tourists want others to strive and enjoy together the result and common grasslands while the involvement in conservation is reduced. This may be because the power of the example is not well understood. A lack of tourism education results from the fact that activities of observation of fauna and flora are preferred, but the overwhelming majority of the respondents do not ask for professional guiding services. This is, in fact, consistent with the fact that “Romanian ecotourism is a sensitive field that needs national legislation to protect natural resources. The Romanian potential and the progress made in the field in the last decades highlight the need for greater involvement of the authorities in this regard.” [29].

4. Conclusions

A positive aspect is the fact that the Rodna Mountains National Park is one of the most popular protected areas. Moreover, tourists have a good general impression about interaction with mountain and protected areas and they prefer internal destinations as opposed to foreign ones regardless of the season. Allotted budgets per night, for a stay and annually are quite high, so the purchasing power is great, these being a solid foundation for decisions regarding the development of tourism supply in the area. The need for holidays and the savings that tourists make over the year, regardless of their income level, lend this opportunity to viability.

Some recommendations regarding tourists’ behaviour would be that they shall respect the protected area and subculture and local traditions, by reducing the level of pollution and respecting the conservation and protection measures of the area. They can also take a proactive attitude by organizing waste gathering events, cultural events and even setting up companies to provide hospitality services.

The findings of this research also lead towards the idea [30,31] that Rodna as a tourist destination must further focus on adopting development strategies that capitalize on its own capabilities, thus developing and managing its individual resources, transforming them into attractive tourist products, consistent with the image it desires to create and promote. Furthermore, the need for coordination also emerges; in this respect, the authors have published other research papers addressing this issue and how such a process can be achieved. Obviously, Rodna cannot simply rely on developing on its own, it also needs to establish close ties, building inter-destination bridges, with its neighboring communes and also with more developed and successful similar destinations from other European countries. Moreover, its development strategies must also consider an integrated approach, building on its natural resources and on its folklore, local traditions and multicultural heritage [32].

The awareness of all these aspects is the first step in change and this is the true purpose and true significance of this paper. The hope that this first step will lead to as many others as possible in a straight line towards the common final goal, namely the improvement of living conditions and the capitalization of natural resources, is omnipresent between the lines of this paper. The survey was heavily distributed on most online Romanian groups with interests in mountain tourism and protected areas, as well as offline among tourists who visited Romanian protected areas in 2017. The relatively small number of respondents brings some limitations to the research, the results being representative for the sample in question, but they may differ for another sample and for another context. This is due to the very low rate of responses obtained in the case of online surveys, which do not allow a proper stratification of the population, as in the case of public opinion polls. Further research may solve this limitation and, also, show how the aspects discussed are evolving in time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-C.C., M.-M.C. and C.P.; methodology, A.-C.C. and M.-M.C.; software, A.-C.C.; validation, A.-C.C., M.-M.C. and C.P.; formal analysis, A.-C.C., M.-M.C. and C.P.; investigation, A.-C.C. and M.-M.C.; resources, A.-C.C., M.-M.C. and C.P.; data curation, A.-C.C. and M.-M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-C.C., M.-M.C. and C.P.; writing—review and editing, A.-C.C., M.-M.C. and C.P.; visualization, A.-C.C., M.-M.C. and C.P.; supervision, M.-M.C.; project administration, A.-C.C.; funding acquisition, A.-C.C. and M.-M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article. Data is contained within the article or supplementary material (The data presented in this study are available in [Cozma, A.-C.; Coroș, M.-M. Dezvoltarea turismului în Parcul Naţional Munţii Rodnei: Administraţia publică, actor central. Revista de Turism 2018, 89–94].)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Coroș, M.M. Managementul Cererii și Ofertei Turistice; CH Beck: Munich, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Regional Development and Tourism (MRDT). Romania Tourism Brand: Driving Values & Visual Identity (Brand Manual). 2011. Available online: https://issuu.com/mdrt/docs/ (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Ministry of Tourism. Romania Travel, Portalul Oficial al României ca Destinație Turistică Internațională. 2019. Available online: www.romania.travel/ (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Davidescu, A.A.M.; Strat, V.A.; Grosu, R.M.; Zgură, I.D.; Anagnoste, S. The Regional Development of the Romanian Rural Tourism Sector. Amfiteatru Econ. 2018, 20, 854–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucculelli, M.; Goffi, G. Does sustainability enhance tourism destination competitiveness? Evidence from Italian Destinations of Excellence. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogârlaci, M. Rural tourism sustainable development in Hungary and Romania. Quaestus Multidiscip. Res. J. 2014, 210–222. Available online: https://www.quaestus.ro/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/ogarlaci4.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Stănciulescu, G.; Lupu, N.; Ţigu, G.; Titan, E.; Stăncioiu, F. Lexicon de Termeni Turistici; Editura Oscar Print: București, Romania, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jugănaru, I.-D.; Jugănaru, M.; Anghel, A. Sustainable tourism types. Ann. Univ. Craiova Econ. Sci. Ser. 2008, 2, 797–804. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, D. Participatory development: An approach sensitive to class and gender. Dev. Pract. 1997, 7, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramwell, B.; Higham, J.; Lane, B.; Miller, G. Twenty-five years of sustainable tourism and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism: Looking back and moving forward. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhambetova, Z.S.; Mataeva, B.T.; Zhuspekova, A.K.; Zambinova, G.; Omarkhanova, Z.M. Green Economy in Rural Tourism. Ser. Soc. Hum. Sci. 2019, 6, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Tănase, M.O.; Nicodim, L. Mountain Tourism at the Beginning of the 21st Century. In New Trends and Opportunities for Central and Eastern European Tourism; Nistoreanu, P., Ed.; IGI Global Book Series Advances in Hospitality; Tourism, and the Services Industry (AHTSI): Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 94–107. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). 9th World Congress on Snow and Mountain Tourism, Sant Julià de Lòria, Andorra, 2–4 March 2016; Conclusions. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/imported_images/42770/8_0_conclusions.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Duglio, S.; Letey, M. The role of a national park in classifying mountain tourism destinations: An exploratory study of the Italian Western Alps. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 1675–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinică, V. The environmental sustainability of protected area tourism: Towards a concession-related theory of regulation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzmann, E.; Job, H. Developing a typology of sustainable protected area tourism products. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitraș, D.E.; Mureșan, I.C.; Jitea, I.M.; Mihai, V.C.; Balazs, S.E.; Iancu, T. Assessing Tourists’ Preferences for Recreational Trips in National and Natural Parks as a Premise for Long-Term Sustainable Management Plans. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souca, M.L. Revitalizing Rural Tourism through Creative Tourism: The Role and Importance of the Local Community. Mark. Inf. Decis. J. 2019, 2, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser-Segura, D.; Nistoreanu, P.; Dincă, V.M. Considerations on Becoming a World Heritage Site—A Quantitative Approach. Amfiteatru Econ. 2018, 20, 202–216. [Google Scholar]

- Jauca, D. Rezervație a biosferei—Prezentare Generală. In Monografia Comunei Rodna Veche; Editura Charmides: Bistrita, Romania, 2013; pp. 273–287. [Google Scholar]

- Romanian Government. Monitorul Oficial No 781/2008. 2008. Available online: http://idrept.ro/DocumentView.aspx?DocumentId=00116524 (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Romanian Parliament. Monitorul Oficial No 152/2000. 2000. Available online: http://idrept.ro/DocumentView.aspx?DocumentId=00033752 (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Romanian Parliament. Monitorul Oficial no 387/2009. 2009. Available online: http://idrept.ro/DocumentView.aspx?DocumentId=00122732 (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Map of Rodnei Mountains Map. Available online: https://haarkleurenfotos.blogspot.com/2018/05/harta-muntii-rodnei.html (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Regia Naţională a Pădurilor (RNP)—Romsilva, Administraţia Parcului Naţional Munţii Rodnei (APNMR) R.A. Raport Privind Activitatea Desfăşurată în Anul 2016 de Către RNP—Romsilva- Administraţia Parcului Naţional Munţii Rodnei R.A. 2017. Available online: www.parcrodna.ro/fisiere/pagini_fisiere/68/Raportul%20de%20activitate%20al%20APNMR%202016.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- Manusaride, D. Cele mai Populare Parcuri Naturale de pe Terra. 2015. Available online: http://ghideuropean.ro/cele-mai-populare-parcuri-nationale-de-pe-terra/ (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- National Institute of Statistics (NIS). Tempo Online—Statistical Data. 2020. Available online: http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/ (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Cozma, A.-C.; Coroș, M.-M. Dezvoltarea turismului în Parcul Naţional Munţii Rodnei: Administraţia publică, actor central. Revista Turism 2018, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Nistoreanu, P.; Aluculesei, A.-C.; Avram, D. Is Green Marketing a Label for Ecotourism? The Romanian Experience. Information 2020, 11, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țigu, G.; Garcia Sanchez, A.; Stoenescu, C.; Gheorghe, C.; Sabou, G.C. The Destination Experience through Stopover Tourism—Bucharest Case Study. Amfiteatru Econ. 2018, 20, 967–981. [Google Scholar]

- Haugland, S.A.; Ness, H.; Grønseth, B.-O.; Aarstad, J. Development of Tourism. An Integrated Multilevel Perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistoreanu, P.; Nicodim, L.; Tănase, M.O. Traditional Profession—Elements of Tourist Integrated Development in Rural Areas. Amfiteatru Econ. 2009, 11, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).