Abstract

The population is getting old, and the use of technology has improved the quality of life of the senior population. This is confirmed by the increasing number of solutions targeting healthy and active ageing. Such solutions keep track of the daily routine of the elderly and combine it with other relevant information (e.g., biosignals, physical activity, social activity, nutrition) to help identify early signs of decline. Caregivers and elders use this information to improve their routine, focusing on improving the current condition. With that in mind, we have developed a software platform to support My-AHA, which is composed of a multi-platform middleware, a decision support system (DSS), and a dashboard. The middleware seamlessly merges data coming from multiple platforms targeting health and active ageing, the DSS performs an intelligent computation on top of the collected data, and the dashboard provides a user’s interaction with the whole system. To show the potential of the proposed My-AHA software platform, we introduce the My Personal Dashboard web-based application over a frailty use case to illustrate how senior well-being can benefit from the use of technology.

1. Introduction

As the population ages, it is rather vital to guarantee solutions for healthy and active ageing [1,2]. One can come across different solutions focused on the well-being of the senior population [3,4,5,6]. The main goal of such solutions is to gather data about the daily routine of the elderly to produce relevant information about how they live and how their choices affect their ageing. The impact and relevance of these solutions on senior well-being are evident [7]. However, these solutions have very specific purposes, such as monitoring and providing feedback on nutrition, cognitive function, social interaction, sleep, psychological state, physical activity, to name a few. This explains why these solutions are focused on integrating specific sensors (or set thereof), and sometimes are more concerned with data acquisition than providing a solution that is less stigmatising to the already sensitive target population, i.e., seniors.

It is this lack of complementarity among the available solutions that motivates our work: we believe that the quality of life of the elderly could be further improved, and caregivers could deliver better treatments if metrics, features, and intended purpose of these solutions were merged into a single solution, allowing data from different sources to be seamlessly combined into relevant information.

Furthermore, the proposed solution focuses on identifying and mitigating early signs of decline considering data from non-stigmatising wearable sensors and from the environments where older adults live. Thus, it targets the monitoring of senior health and offers a means to support disease prevention by considering the individualised profiling of users with personalised recommendations, feedback, and support.

My-active and healthy ageing (My-AHA), an EU consortium [8], proposed an Information and Communications Technology (ICT) platform for early detection of frailty. Thus, a sustainable ageing intervention can be carried out to reduce declines. The platform’s main objective is to reduce the risk of frailty, contributing to healthy physical activity, cognitive and psychological function, and the general well-being of the elderly. Additionally, it provides training of the elderly to manage their health, new types of health monitoring, and disease prevention.

With that in mind, we have developed a software platform to support My-AHA which comprises a middleware [9] capable of seamlessly integrating multiple healthy and active ageing platforms. Hence, in this paper, we present our proposed My-AHA software platform which consists of a middleware coupled with a DSS, and a front-end dashboard, named “My Personal Dashboard”. Our proposed My-AHA software platform is developed focusing on the use case for early detection of frailty, providing the means for users (i.e., caregivers and seniors) to understand and improve their current condition considering changes to cognitive, physical, social, and psychological parameters.

The contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- Development of a multi-platform middleware that seamlessly integrates health and ageing solutions to harvest data and post-process it into information to provide support for early detection of decline in different domains (e.g., psychological, physical, cognitive, social).

- Development of an easily integrable library in the form of a Java SDK that allows third-party applications to interact and use the features of My-AHA through its API, and perform analysis and/or machine learning over the data gathered by My-AHA platform.

- Development of a decision support system that provides guidance and motivation to further reduce the development of frailty. The proposed DSS computes personalized risk scores to monitor the condition of participants and create awareness. It comprises a Java application that listens to new metrics in the middleware and calls the computational engine developed in R in an event-based fashion. In addition, interventions and high scores can be calculated in a time-dependent way to promote a healthier lifestyle.

- The development of My Personal Dashboard that has been designed to provide a unifying layer to users, as an entry point of the senior into My-AHA system. It is a Single Page Application, responsive and accessible through the main recent browsers on the PC and on smartphones, in particular Firefox, Google Chrome, and Microsoft Edge on the pc and the latest versions of the browsers in the mobile platforms (Android and iOS).

This paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we describe ICT-based work that, at different levels, targets frailty, and that provides the basis for carrying on the proposed work, while Section 3 details the proposed platform of My-AHA. Section 4 presents how the My-AHA project supports frailty early detection and prevention. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

This section goes over literature work that is related to (and also helped to build) the proposed My-AHA software platform. The section starts by providing a brief overview on platforms and software architectures that also (or could be used to) target frailty. Then, it presents different solutions concerning My-AHA’s main components, namely the multi-platform middleware, DSS and personal dashboard centred on the detection of early signs of health decline.

It is worth mentioning that our goal in this section is not to provide a detailed analysis of the related work concerning platforms, software architectures, middlewares, DSSs, and dashboards. Instead, we focus on the relevance of healthy and active ageing solutions, and how My-AHA stands out in the case of frailty early detection and prevention.

There are different works specifically on ICT-based platforms and software architectures that focus on the early detection of frailty to help caregivers and seniors [10,11,12] or that could be used to target frailty [13,14]. Abbasi et al. [10] evaluate the acceptability of tools that identify signs of frailty based on their literature review, including the PRISMA-7 (a tool composed of yes/no questions), a 4-m walk test to assess the gait speed and the calculation of the electronic frailty index (eFI) score (it required the training of an assistant to calculate it for every patient). Their conclusions show that less disruptive and more informative tools are highly accepted among caregivers. This is in line with the approach of My-AHA in combining data from different platforms to aid caregivers. It is worth noting that some of the considered tools are not very scalable since they require trained personnel to go over the gait analysis and the eFI score calculation individually for each case, for instance.

Lunardini et al. [11] approaches the frailty detection on a home-based monitoring with the aim to support the independent living of the elder at home. To achieve this, the proposed MoveCare project used a subset of sensors, each one specialized to monitor a specific frailty sign, from weight values, low activity, questionnaires, grip strength etc. To detect unintentional weight loss, which can cause older adults to be more vulnerable, it used a specific model of a Beurer scale. To measure maximal grip strength, a smart anti-stress ball was designed and implemented specifically for this project. To obtain gait parameters it used a smart pair of shoe soles. The project also had some sensorized daily-use objects and an exergame component using the Nintendo Wii to monitor the daily activity of the patient. Another way of early identifying cognitive decline is through a series of spot questions that are asked to the elder. The main drawback of MoveCare is that it is tightly coupled with the specific sensor models used, and it could clearly benefit from a solution such as My-AHA by having access to more data from different platforms to more reliably identify frailty.

Zacharaki et al. [12] developed a system with the ambition to identify the most important signs of frailty and apply the insight and expertise for self-management and prevention. The FrailSafe architecture is based on a Big Data architecture for IoT. It is somewhat similar, component wise, with the My-AHA approach in that it has a dashboard to provide controls on the system to the doctors and data visualization to the patients. And it also has a back-end component with a data analysis module and a decision support system module. The difference when compared to My-AHA is that as the architecture relies on a gateway to resolve the communications between the sensors and the system, and therefore the system needs to know how to communicate with every sensor, which may affect scalability given the different sensors interfaces. This lack of an abstraction layer that enables easier integration with other platforms could be complemented with our My-AHA solutions.

There are also few architectures in the Internet of Things (IoT) domain that could be used to address frailty. Alreshidi and Ahmad [13] go over several types of architecture that can be used for IoT-based systems, and that could serve as basis for our work. Within the context of the authors classification, My-AHA architecture can be labelled as a “Reference Architecture for IoTs” as it provides generic and high-level (abstract) solutions that can be instantiated with specialized architectures such as IoTs devices. My-AHA decided to go with this type of architecture with the purpose of providing a reference framework (our Java SDK) that serves as a template with documented guidelines that allow high-level abstraction between systems. Also, this sort of architecture approach allows us to focus less in IoT connection, its quirks, and lack of standards, being more focused on creating a multi-platform middleware system, that integrates already existing platforms and is coupled with a with a DSS and a dashboard targeting sustainable ageing.

Manogaran et al. [14] proposes the use a Big Data architecture model for health care applications. The architecture consists of using IoT sensors to monitor the patient health condition, and the obtained data is continuously stored on the cloud. To protect the data, the cloud component also includes a security layer. Once stored, the monitoring system runs an algorithm with a prediction model for heart disease. By using a Big Data model, the proposal is a data-driven system, focusing on having a distributed scalable database, data analysis, and efficient data processing and storage. This approach also comes with its drawbacks, such as complex implementation and deployment and needing frequent maintenance. On the other hand, a middleware-oriented solution, like the one used in My-AHA, focuses on adding several layers of abstraction, defining a set of guidelines for the easy deployment of new platforms to the system.

Regarding middleware for health monitoring, Alonso et al. [3] considered the benefits of employing middleware solutions for Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) by providing a simple interface to access the underlying resources to simplify development. The study analysed several types of middleware, reviewing which requirements and desirable features a SHM system should have. The study recognises that adding a middleware layer provides an abstraction layer to ‘hide’ the complexity of handling the particularities of each hardware platform, such as wireless communications, power management, and low-level programming. This simplifies the integration with the new IoT devices and Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) by offering a high-level programming model for the development team. This aligns with My-AHA’s feature of providing a seamless way to gather data from different sources (i.e., platforms) to support the early identification and prevention of declines.

A hardware middleware device that handles the communication with the available sensors to retrieve the requested data was developed by Georgi et al. [15]. In this solution, the user requests a specific data type, not a sensor model; then the middleware retrieves the available devices for the requested data type. Thereafter a discovery service is launched to connect and retrieve data from the list of supported sensors. The solution also stores the credentials provided by the application’s developer for each sensor using a credentials manager component and supports sensors from some manufacturers. This application stores measured data in a local database and then displays them on a chart. While this solution relates to My-AHA from the API abstraction perspective, the main difference resides that it focuses on the sensors, and not in the platforms as proposed by My-AHA.

A middleware framework for the Health Information System (HIS) of National Taiwan University Hospital was created by Ko et al. [16]. This framework is a Service-Oriented Architecture which integrates heterogeneous platforms and databases while using the HL7 standard to cover all the data exchange. The HL7 standard defines how information is packaged and communicated from one party to another, setting the language, structure, and data types required for seamless integration between systems. Hence, the transition from the legacy system into the proposed system should be effortless. The middleware is divided in three components: HL7 Message Modules, Central WebService, and Sub-System Handlers. The first module is used to format all the messages exchanged across systems. The Central acts as the front-end of the data exchange. It receives and parses a received message and then dynamically loads and invokes correspondent sub-routines defined in the Sub-system component. The authors reported that the middleware was serving approximately 8000 outpatients a day. This solution is more focused on its middleware framework and not on the whole ecosystem of software when compared to My-AHA that focuses on bridging the gap between the technology, the data, and the users themselves.

Hofer et al. [17] suggested an interoperable personal health system to monitor the obstructive pulmonary disease. The architecture follows a server-client RESTful architecture with a publish/subscribe mechanism running on Android devices. The mobile device acts as a data collector with a continuous connection to the sensor and broadcasting the fetched data to a remote server for storage and later processing. A multi-sensor medical device is used to collect the data and measure several vital signs such as blood oxygenation, heart rate, skin temperature, and steps count. With all the obtained information, a machine learning component then calculates new models and refines them regularly. The server then pushes the refined models to the clients using a publish/subscribe mechanism. This paper does not focus on features such as abstraction and a modular solution, focusing more on supporting one device featuring multiple sensors which connect to the phone. This approach diverts from the one applied in My-AHA, where the focus was on the seamless integration of solutions already available on the market.

With a rapidly growing health care sector, research has tried to apply well-known decision support systems in the field of medical care. Focus rested on clinical applications that support finding an accurate diagnosis, improving treatment, or optimizing medication. For example, Roshanov et al. [18] studied the effectiveness of DSS systems employed in a clinical environment for chronic disease management. Several studies to determine if a DSS can improve the processes of chronic care, including diagnosis, monitoring and treatment, are presented. This study reviewed 55 trials from 71 publications. The results show that 87% of those trials measured system impact on the process of care. Furthermore, 65% of those demonstrated impact on patient outcomes and 31% showed a clear benefit on measures such as health-related quality of life, rates of hospitalisation, unscheduled care visits, and a host of disease-specific clinical outcomes. This work shows not only the importance of a DSS, but also provides insights that the more data is available to a DSS, the better it shall aid in prevention and treatment. This explains our choice of proposing the My-AHA platform that works on top of a different sourced data and builds relevant information to mitigate decline.

Until now, few DSS approaches tried address problems arising with aging societies. Personalized analysis and interventions are often missing. In addition, most systems monitor instead of advising or preventing the elderly decline. One example is the USEFIL platform [19], which aims to support active and healthy aging and even analyses data in a personalized fashion but fails to go beyond monitoring to alert users when recognizing abnormalities or health decline in the data.

In what concerns DSS for health management, Billis et al. [20] DSS’ monitors health assessment indicators on an ongoing basis, calculating the risk assessment and the seniors’ progression of depressive symptoms, alerting the caregivers with useful information and allowing a swift adjustment on the patients’ treatment accordingly. In an European project, Orte et al. [21] invented a multi-domain solution with a DSS to support elderly and their active aging. While an evaluation is not given, the focus lies on the methods and algorithms of the proposed DSS. Static and dynamic information from wearables and the environment is collected to provide so-called coaching plans. Users are able to choose from a list of proposed activities. While the first solution lacks any interventions plans, the seconds does not provide any detailed information about the current health status to predict risk factors. Here, My-AHA addresses both problems by implementing a more complete system.

In addition, focused approaches based on one modality have been realized as well. Billis et al. [22] implemented a system with the smart collection of TV usage patterns to enable active and healthy aging. Several health-related problems, like depressive symptomatology such as loss of interest in daily activities, depressive mood, sleep deprivation and total depression levels, could be associated with TV watching time. Although interesting findings and a helpful platform could be realized, My-AHA aims to provide more support by invoking a multimodal approach using different platforms.

From the perspective of the dashboard, My-AHA is a modular system, connecting in a complex platform multiple actors and platforms. One potential barrier for elderly users of the My-AHA platform is the technological layer. It is therefore imperative that the end user interface of the platform will be designed to help elderly users to adopt it and to receive stimuli toward healthy practices and active aging.

Even though the appropriation is defined as an individual process, it can also be cooperative. Considering that the collaborative appropriation is recognized as an important success factor [23], it would be useful to address it on My-AHA. The relationship between the subject and the healthcare professional (HP) is an object of study of several disciplines (medicine, anthropology, sociology, psychology) in order to understand the internal dynamics of the interaction and figure out if and how they can influence the results of the therapy [24]. This type of relationship can be established on three objectives: (1) to create a good interpersonal relationship; (2) exchange information; and, (3) make decisions about the type of treatment [24].

Some authors focus specifically on the role played by the HP across the various contexts of interaction. In fact, Lussier and Richard [25] argue that the HP attitude towards the interaction is strongly influenced by other aspects, such as the disease characteristics reported by the subject (i.e., the type of disease and its severity); the physical location where the interaction takes place (i.e., the surgery, the medical office, the emergency room, the patient’s home); and finally by the actors involved.

The interaction between the HP and patient can affect the results of the therapy. In particular, communication style can influence the results of the treatment even after some time away from the first consultation. Effective communication between the subject and HP can facilitate the process of care through indirect pathways, encouraging mutual understanding and the reinforcement of the therapeutic alliance, resulting in a greater treatment adherence. Effective verbal communication provides visible benefits for both parties: empathy from the HP enhances the emotional status of the patient in a positive loop promoting the psychological well-being through the reduction in negative emotions and an increase in positive emotions. Additionally, it fosters motivation about continuing the treatment.

The cooperative appropriation, based on relationship and cooperation among primary and secondary users, as well as included systems and platform, implies organizational preconditions that the design of the system has to address. In a socio-technical perspective, the system and its technical features must be deeply interrelated with the organizational and social context. This requires a holistic approach able to bring comprehensive, empathic understanding of users’ needs.

The theoretical models previously considered highlight the importance of the practice and the experience for the appropriation. The quality of the experience and the usability are core bricks that ground on the Human Factors methods and techniques.

The Human Centred Approach, historically set as a fundamental approach of Human Factors, Ergonomics and Human-Computer Interaction, is nowadays core in innovation design also [26,27,28,29]. The collection and understanding of the users’ needs and the context of their activities is the knowledge base and the main reference for each design and development phase. A set of tools and methodologies allow for gaining insights and understanding about every end users’ and stakeholders’ perspective (including mind-sets and background experiences) and the overall context. This approach sets the priority on the effectiveness and usability of the solution, ensuring sustainable processes and sense of co-ownership that serves as a base for building a long-term period end-user engagement. The Human Centred Approach is commonly adopted in the majority of research, design, and development in the field of tele-healthcare, tele-medicine, and tele-rehabilitation. The effectiveness of remote systems dedicated to the health depends not only on technology, but also on a careful design of the human—computer interaction [30].

In My-AHA, when designing innovative services, systems, and applications for the healthcare domain, it has been useful to adopt a user-centred approach, with particular attention on the usability of the system (ISO 9241/11) to be designed and evaluated in consideration of real users and everyday contexts of use. A usable system will be pleasant and easy to use, able to foster a functional alliance with the users that will experience accuracy, efficiency, satisfaction.

The above assumptions have provided useful input to bring into the My-AHA system some elements of a working appropriation strategy. It has been important to bear in mind both the technological and socio-organizational constraints [31]. From one hand, technology should help to decrease the workload of the individual. For instance, My-AHA dashboard supports the primary users in managing possible specific risks, following personalized activity plans; for the HP, they receive support in patient management and prescribe wider and personalized activity plans. On the other hand, it is important to be aware that technology increases the complexity of the interaction (Norman, 1988) due to mediation and remoted interaction, leading to a modification of the relational styles and procedures embedded in the clinical process.

Another design challenge has consisted in the clash between the needs and mental models of all targeted users that differ per age, expertise (on both the health domain and technology), country, and other variables. The system particularly works with the knowledge gap between the HP and primary users, including the so-called non-technical skills [32], products of experience that are difficult to export into the digital environment.

Considering these assumptions, the My-AHA dashboard provides an effective communication environment, inspired by real interactions and successful practices of the HPs and end users. Moreover, the system exploits the strategies and features of all the My-AHA platforms, aiming at stimulating and reinforcing proactivity and positive behaviour in their target.

Looking at these platforms, software architectures, middlewares, DSSs, and dashboards, one can see that My-AHA’s solution is not focused on the sensors/end-devices (or set thereof) from which we can get data. It rather focuses on providing the means to integrate different healthy and active ageing platforms (cf., Section 4) regardless of (i) the type of sensor/end-device they have (proprietary or not); (ii) the measurements they perform, and (iii) their specific goals. The My-AHA software platform’s novelty (further detailed in Section 3) relies on seamlessly combining data from multiple commercially available platforms (i.e., through API’s abstraction) and providing straightforward access to a variety of metrics. Moreover, it opens the possibility of these metrics for being post-processed into relevant information, which in our application scenario include the detection of cognitive, physical, social, psychological declines, but could be easily adapted for a different scenario.

Finally, My-AHA proposal differs from the analysed works as, besides having all the mentioned characteristics, it also provides a Java SDK to enable smooth and seamless integration of external entities with our proposed software platform speeding up this integration process. Another unique feature is the provision of methods that allow post-processing of measurements, even from external entities. Such methods allow the integration of systems such as the advanced DSS with functionalities to allow early frailty risk detection and intervention (i.e., prevention) and a platform targeted to the interface with the users which offers a dashboard where they can interact with the system in a simplified way.

3. Proposed My-AHA Software Platform

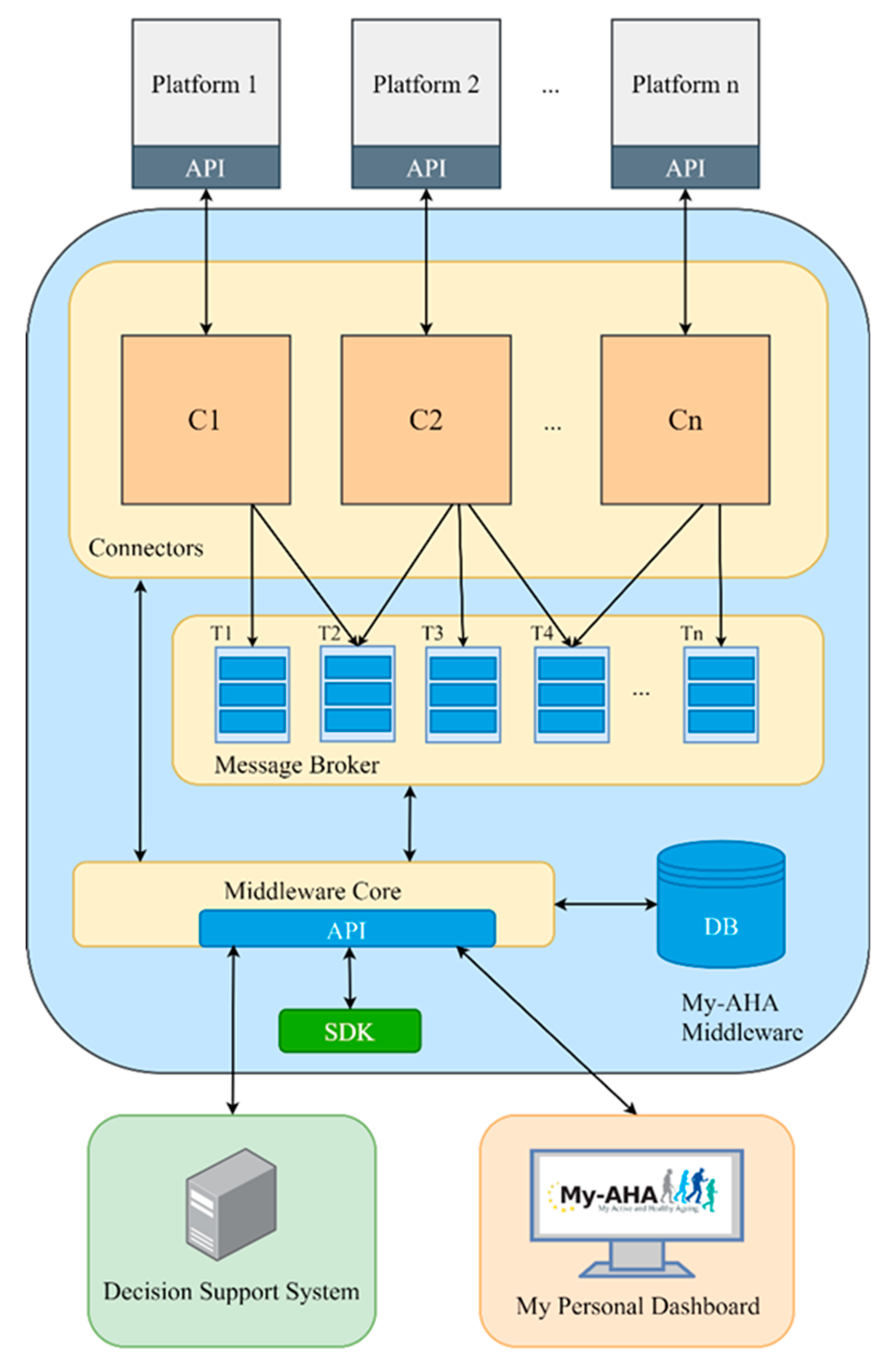

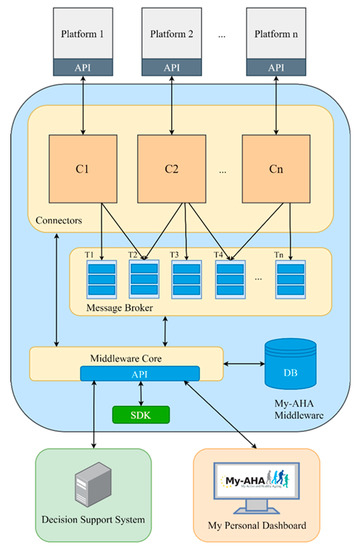

The proposed software platform for My-AHA is a modular, fully scalable, and easily deployable system. Figure 1 presents an overview of this platform, its main components, and their interoperability, which are further detailed next.

Figure 1.

High-level overview of the My-AHA software platform.

3.1. Middleware

Following a top-down approach, this section starts with a description of the inner components of the middleware presented in the My-AHA software platform (cf., Figure 1).

3.1.1. Middleware Connectors

One of the key components of the middleware and a critical component of My-AHA is the set of modules called connectors. The connectors are the software modules responsible for checking if new data is available at the external platforms they are interfacing for My-AHA, and, if there is, securely fetching this new data and storing it locally. These background services are periodically triggered, autonomously searching for new data on behalf of all the registered users which granted access to external platforms.

Since the sensors’ communication protocols change from sensor to sensor, and data is processed differently (or not even on the sensor itself), the interfacing with the sensor is performed through the third-party platforms. This way, it is up to those platforms to assure the communication and data processing of sensor data. Also, since is not out of the scope of the project to develop an end-user device or even communicate directly with isolated sensors, with this approach, we can focus on the middleware software interfacing with the external platforms. This approach specifies that the main requirement for an external platform for being integrated into our middleware is to have an accessible API capable of accepting requests on behalf of users. Another advantage of such an approach is that the amount of code necessary to connect to a platform with multiple sensors is highly reduced compared to connecting to the sensors individually since the connection and authentication mechanisms are shared among all the devices present on that platform. Usually, the queries to retrieve different data from the same platform are also very similar, streamlining this introduction of new devices.

The connectors go through the list of middleware registered users who have previously authenticated and authorised access to each third-party platform to query for new data. The association of the user account to one of the supported external platforms is performed through a dedicated web interface (Section 4.5.3). There, the users can check the list of the supported platforms, and they can select the platform and grant access to the middleware. After the selection of the platform, the user is redirected to that platform’s authentication page, showing which information is being shared with the My-AHA platform. In case the user is successfully authenticated, the respective authentication token is sent back to My-AHA for further interaction with the platform by the middleware on behalf of the user. Those further interactions are done through third-party APIs dealing with the respective users’ authentication and authorisation mechanisms. At any time, the user can go to the web interface and disconnect the middleware from the third-party platform, stopping any further interactions between the two entities.

This set of connectors was built to be modular. All the connectors follow the same structure, varying only on the specificities that each platform imposes. By following this standard structure, the process of adding new connectors and replacing old/outdated ones was highly simplified. Such changes on the list of available platforms are easily implementable, as we need to guarantee that the external platform exposes APIs that implement the necessary security mechanisms for user authentication and further calls on behalf of the user and allows for data querying.

The data fetched from each external platform is decomposed into the supported parameters and sent to a message broker in a pre-defined format for later handling.

3.1.2. Middleware Message Broker

Since the proposed middleware platform follows a message-driven scheme, a message broker can be adopted. The message broker provides several topics (i.e., channels to which clients can subscribe to receive messages). Each topic (cf., blue blocks in Figure 1) holds data retrieved by the connectors from platforms and published into the topics as messages. Each topic is associated with a single parameter considered for frailty assessment (e.g., weight, blood pressure, walking time, etc.) where all the data retrieved from the external platforms related with that parameter is inserted. This message broker works in a publish/subscribe model. The connectors are the ones responsible for retrieving the data and publishing it in the topics. The subscription of a respective topic is required to receive updates regarding a specific parameter. The proposed architecture allows multiple publishers and subscribers for the same topic. As for some parameters, we might have an overlap of third-party platforms providing concurrent data (e.g., different wristbands tracking activity monitoring), which means that the respective connectors will be publishing data into the same topic. The information is distinguished by tagging the source of data. Therefore, the client can identify it, but the structure of the data itself becomes platform agnostic.

3.1.3. Middleware Core

The middleware core is the centrepiece of the middleware platform. It is the component that orchestrates the functioning of all the other ones. It periodically (i.e., currently on an hourly basis) triggers the connectors to initiate a new run and search for new users’ data on the connected external platforms. It handles the deployment of the middleware API described in Section 3.1.4.

The middleware core is itself one of the subscribers of the message mentioned above broker. It is responsible for creating all the message topics inside the message broker, and for subscribing to all of them. By doing this, it can listen to all the updates on measurements and properly store them on the local database with the pre-defined structure. With this approach, on subsequent contact with the third-party data provider, we look only for newly available data since the previous call.

As the data and respective structure are very different for each of the healthy and active ageing solutions to interface with My-AHA (and shall not be modified), a NoSQL database is adopted since flexible models are required to put them all together. This database stores all the user profiles, data retrieved from original solutions, knowledge, and recommendations generated by the DSS and parallel algorithms for frailty assessment.

The middleware core is also responsible during this local data storing process to check for measurements, either individually or grouped, which have associated and do the necessary processing (further described in Section 4.2). One example of such rules are the individual goals, better described in Section 4.5.5.

3.1.4. Middleware API

No external component interacts directly with the middleware core. As previously described, the core deploys a RESTful API that interfaces external clients with the system. This API exposes several methods that allow for external components to interact with the My-AHA system in a secure and simplified way. These methods allow for fetching the requested data from the database, ranging from measurements to user profiles to and all the associated parameters.

Moreover, it is through this API that the DSS platform connects and access the middleware data and stores its outcomes (details in Section 3.2). It also provides the needed methods for the dashboard to manage and visualise the user’s information and data in a more user-friendly way (further described in Section 3.3).

To guarantee the security of the data, this API has a security layer to restrict access to those who are not authorised or do not have access to perform some actions. So, applications must complete the authentication process to be able to call the API methods successfully.

3.1.5. Software Development Kit (SDK)

An SDK was developed, in the form of a Java library, to facilitate the interface with the system. This SDK is an alternative to direct interaction with the API above mentioned and can easily be integrated by any external entity willing to interact with our middleware platform. It implements all the API methods for data management along with the basic functionalities of authentication and token management, which are handled transparently. The API and authentication functionalities allow us to seamlessly integrate with external entities to My-AHA for performing tasks such as data analysis or machine learning over the collected data.

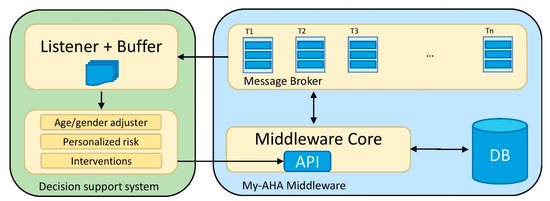

3.2. Decision Support System (DSS)

Moving outside of the middleware platform physical boundaries, we find the first platform of the software ecosystem that interacts with the middleware, the DSS.

To profile participants using the My-AHA platform and provide personalised recommendations, feedback, and support, a DSS was implemented. It aims to support elderly people in monitoring, preventing, and treating frailty in old age, but more specifically to reduce the risk of conversion from pre-frail to frail. The developed DSS software model is the computational engine of the risk model seamlessly integrated into the My-AHA ecosystem by making use of the RESTful API implemented by the middleware. It offers personalised risk values based on the participants’ data and tailored intervention plans to improve their ageing. The risk values are a set of outcomes which are calculated by weighing in specific risk factors for each domain (e.g., the history of strokes has an impact on the physical risk value). The underlying Bayesian probability model (developed by the consortium of the My-AHA project) is based on a wide range of scientific literature. For example, studies such as the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) [33] were investigated to identify relevant risk factors and their effect on frailty. In addition, the model compromises person specific data and prior information as an age and gender adjusted probability. The prior probability based on a population level found in literature is adapted based on a list of risk factors which can be given or not. Data used and the resulting computation are specific for different risk domains. The overall probability calculation can be summarised as follows:

personalized information = personal data × prior information (population level),

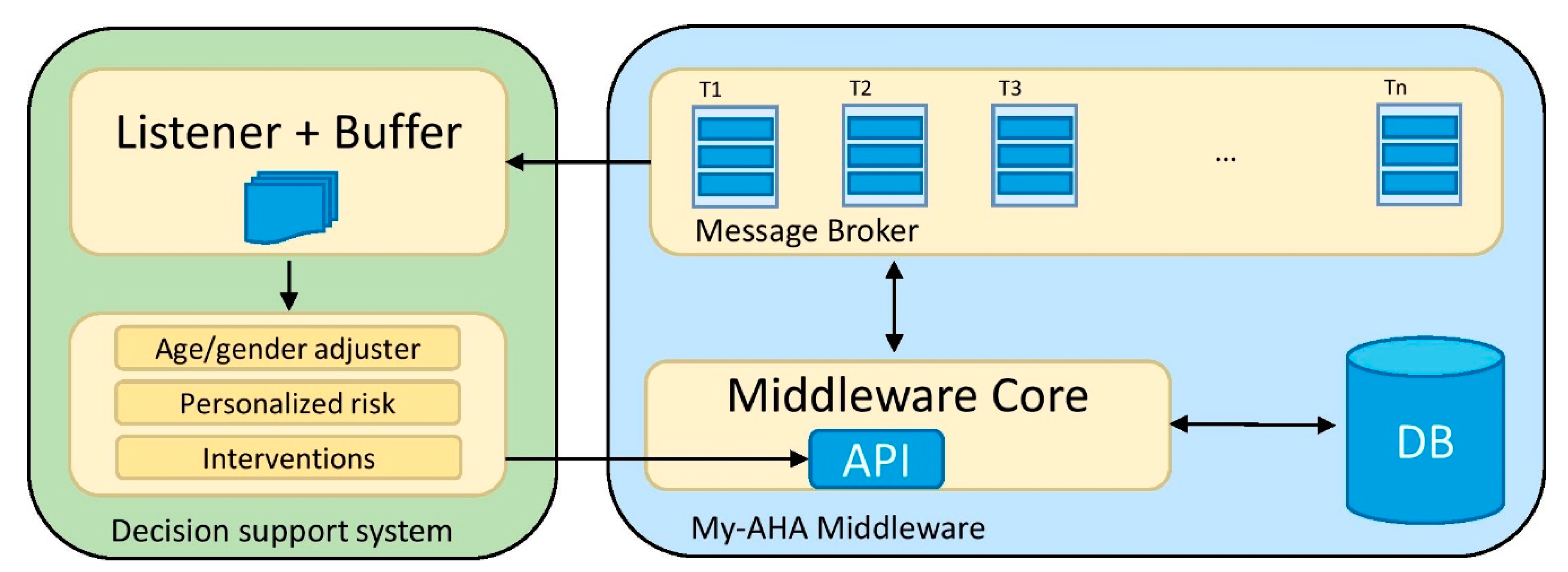

Further, the Bayesian approach allows us to build a modular risk model which can be updated according to evolving scientific findings and further collected data. A similar method to these analyses used during the My-AHA project and more detailed information can be found in the work from Niederstrasser et al. [34]. Figure 2 shows a schematic visualisation of the interaction between middleware and DSS.

Figure 2.

DSS interaction with the middleware platform.

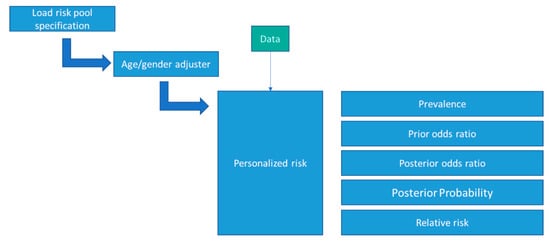

The process is initiated by the DSS which issues a request to the middleware for receiving updates for specific user metrics relevant to calculate the risk value for each domain (e.g., body weight, history of stroke, etc.). A Java application is responsible for receiving relevant changes in participants data. Every time a new entry on the requested metrics list comes in, the application is notified and starts the update process. Messages are bundled according to their associated domain for 200 milliseconds to prevent redundant computations, which could mainly occur when a group of metrics is updated all at once. An example of this could be when participants update the questionnaires in the dashboard and generate 23 new entries for their data. Afterwards, the underling DSS core (written in R) is called to start the computation of risk values.

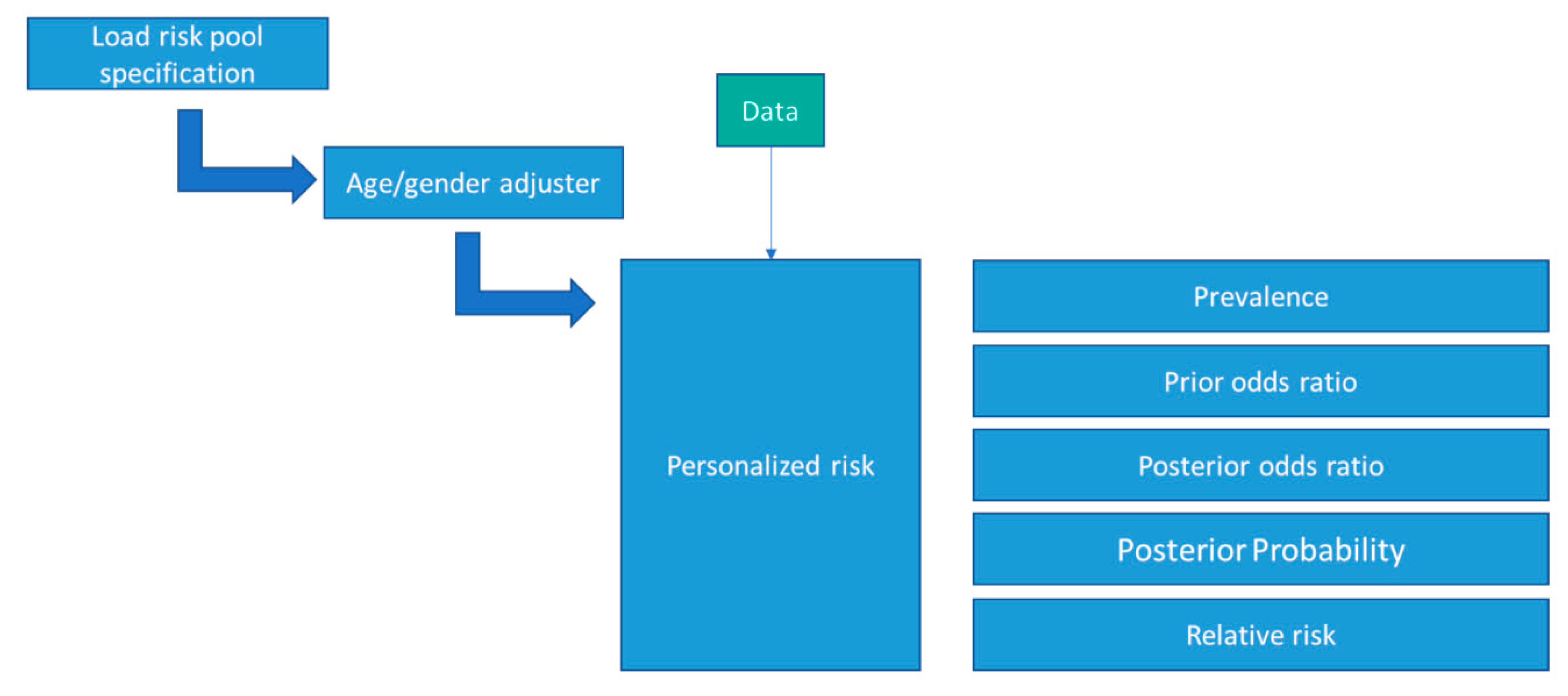

Next, the DSS initiates a multi-step computation process, including a pre-processing task to load a risk pool specification and run an age/gender adjuster. This process is depicted in Figure 3. There, an initial risk is loaded from a pool and the users are categorised by their age and gender. Afterwards, the personalised risk is computed in several different steps. Initially, the prevalence data for age and gender are individually calculated according to the extracted nonlinear weighted regression models for each domain. Next, the probability is converted into an odds ratio (prior odds ratio) which is combined into value for all domains (posterior probability). The relative risk for the user can be given, which is depending on the aimed domain and the individual user data. Five Risk values (Frailty, Falls, Dementia, Depression and Loneliness) are calculated in 4 different domains: Cognitive, physical, psychological, and social. Finally, the outcomes are pushed back to the middleware, from where they can be visualised in participants dashboards (Section 4.5.2 shows examples of these outcomes). Since these outcomes are treated as a standard user metric, a history of the risk values can also be visualised to track its evolution over time.

Figure 3.

The DSS multi-step computation process.

Similar to this process of fetching user data and creating new outcomes, the DSS can provide tailored interventions. Previously, intervention plans could be assigned based on several questionnaires by a clinician during the course of the project. To integrate this assignment as an automated process into the platform, the DSS evaluates individual participants’ data and allocates interventions corresponding to the questionnaires which have been transformed to simple decision trees incorporating the middleware data. For example, physical training sessions or plans to improve sleeping quality will be suggested based on previous training sessions, falls, and insecurities in walking and the measured sleeping time, respectively. Intervention plans and assignments were developed based on a detailed literature search as part of the My-AHA project. Interventions are allocated to the user in the middleware (Section 4.5.4 shows an interface where the user can see and select the assigned interventions).

It is worth noting that although these calculations are user-specific, the DSS is entirely unaware of the user identity. The DSS only receives an anonymised user ID and the user’s metrics, which include the age and gender. It sends back to the middleware the personalised risk-values and intervention assignments, and no other personal data is exchanged.

3.3. My Personal Dashboard

For visual interaction and validation of the healthy models and the intervention plans, a front-end for the elderly involved in the field trials, named My Personal Dashboard, has been realized. It has been designed to provide a unifying layer to users, over the single platforms and organisations, and also to provide a coherent and integrated understanding and experience of the My-AHA system as a whole. The My Personal Dashboard is the visual interface that allows the users of the system (e.g., the elderly themselves directly or the caregivers) to interact with it.

It was built as Single Page Web Application with responsiveness as the main driver in its developments to boost its accessibility since the end-users could be in the group of people which are not very familiar with the usage of technology. The technological approach allows performance similar to traditional native apps inside the web browser. The website is loaded entirely at the beginning, and the only network calls necessary to guarantee its functionalities are calls to API methods for the My-AHA middleware to retrieve/store data. The technology used for the development was React.js [35] alongside with Redux [36], and for handing the responsiveness of the interface React-FlexBox-Grid toolbox [37].

Regarding the data exchanges between the dashboard and the middleware, first, the user needs to start the authentication process and request its credentials. Upon successful authentication, the middleware answers with the OAuth tokens, which are used in the upcoming interactions. Whenever the users introduce a new value of their health status, the platform calls the middleware API to inject a new metric for the logged-in user. These values may trigger the risk-value calculation, which is later transmitted back to the dashboard where the user could see it in a user-friendly tailored interface. More details of this interface can be seen in Section 4.5.

The dashboard is also responsible for initiating the exchange of credentials for the users to link their external platforms with My-AHA. The user selects a platform from the available list (visual example in Section 4.5.3); this selection drives the user to the external platform website to follow their own procedure for authentication. When this authentication is concluded, the external platform reports back to the redirect URL in the dashboard the OAuth tokens necessary for the middleware to perform subsequent queries on behalf of the user. These tokens are sent to the middleware and associated with the user account. So, whenever the connectors are triggered for a new run, these tokens are used.

3.4. Security and Privacy

Although this is not an isolated component like the ones presented before, the security and privacy of the exchange data was a major concern throughout the development phase in the sense that all the communications established between the middleware and the external components recur to the available API methods, which, in turn, require prior authorization and authentication before being able to perform further interactions.

Before data exchange is allowed, an application needs to go through the authorization process where a client ID and secret and the chosen username/password pair are granted to the application. This data will be required for the application to authenticate itself with the system generating the access token required on the subsequent calls to other API methods.

The third-party platforms assure user data privacy, since we are fetching data from these platforms, for which the users had already accepted their end-user license agreements. So, when the user accesses the My-AHA dashboard and selects the external platform, the users grant the middleware access to that data. At this step, the external platforms usually notify the users of which data is being shared with the external platform, in this case, My-AHA. The data is securely stored in an anonymised database alongside its platform and date of origin, date of arrival in our platform, and its corresponding data parameter.

Whenever the user decides to revoke access to new data, he can do it through the same dashboard where it granted My-AHA access to the external platforms. As a result, this stops the middleware from fetching new user data for the corresponding platform. In this case, and for study purposes, the data already retrieved is kept. If a user finds it necessary, he can also explicitly request for all his data to be deleted.

4. Frailty Use Case

Frailty is a progressive process of increasing vulnerability, predisposing to functional decline and, finally, leading to death. It consists in the loss of functional homeostasis, which is intended as the potential for the individual to resist disease without loss of function. Nevertheless, frailty can be perceived from different domains (i.e., cognitive, physical, social, psychological), and My-AHA focuses on detecting changes on such domains by determining levels of frailty to help caregivers and the seniors themselves improve their current condition [38].

To fulfil the main requirement of supporting for early risk detection and intervention in the frailty use case, several additional components and API methods were added beyond the core of the described My-AHA software platform.

4.1. Inclusion of Additional Metrics

Since the goal of the use case is to detect and prevent frailty using a multi-dimensional approach early, we needed to obtain the subject’s data from a wide variety of domains. The list of domains includes Activity Monitoring (e.g., daily activity tracking including steps taken, distance walked, etc.), Fall Risk (e.g., history of recent falls and/or the risk of falling again including the factors leading to this), Physical (e.g., weight, height, blood pressure, etc.), Nutritional (e.g., macronutrients of what the subjects are eating), Social (e.g., social activities or details of the subject, such as, owning a pet, smoking, early retirement, etc.), Cognitive (e.g., scores in cognate tests), Emotional (e.g., prior depressions), and Sleep (e.g., sleeping time and quality).

Currently, My-AHA can fetch data from the following platforms: Smart Companion, an application developed by Fraunhofer Portugal AICOS that besides other features includes an advanced activity tracker and fall risk predictor [39]; VitaDock [40] by Medisana that provides through a vast set of sensors a wide variety of data: activity (e.g., steps, distance, and energy) and sleep tracker, blood pressure, pulse, blood glucose, insulin, carbohydrates, body weight, body temperature, oxygen saturation; CognHome provides scores and all the metadata related with cognitive games; iStoppFalls [41] provides activity data and fall risk scores resultant from the exercises and games played with the platform; Fitbit [42] provides macronutrients data from food logging application and activity data registered by the Fitbit activity tracker.

My-AHA allows connection to platforms that encompass a set of sensors instead of connecting to an individual sensor directly. This opens the possibility to not only integrate additional devices (which may bring different measurements that were not considered before) but also provides more reliable measurements by connecting different devices which may offer some redundancy. An example of such a solution was the case of the sleep tracker. The initially selected sensor was commercially discontinued. Since we were already connecting our middleware to the VitaDock platform [40] by Medisana, it was straightforward to include the ViFit Activity-Tracker [43], which besides the desired sleep tracker also brought in the same package an alternative for an activity tracker.

As already described, one of the main concerns during the conception and development of My-AHA software platform was its modularity, since it would allow for easy replacement of platforms. An example of this was the replacement of the initially selected solution for nutrition recommendation and food logging. The users would use this platform to register what they were eating, and we could later retrieve the nutritional data from the registered food. However, the company providing this platform has ceased activity, and we had to find a replacement for this type of data provider. Taking advantage of the connectors’ modular capability, we could create a new connector targeting Fitbit [42], implementing their APIs for authentication and data handling, and keep retrieving the same nutritional data from a different platform.

A similar situation also happened with the inclusion above of Fitbit. It was initially included as a replacement for Nutrition logging, but since some of the subjects already had activity trackers from Fitbit, with a reduced effort a connector was included to fetch the Activity Tracking data from Fitbit.

With this inclusion, besides widening the range of platforms available on the My-AHA ecosystem, we also provide redundancy, as the data retrieved from Fitbit can also be retrieved from Smart Companion and Medisana. So, one user might not have all the platforms available but can have at least one, increasing the data collection and its availability. Likewise, in a situation where the user has all these devices, the data retrieved from each one is tagged with its origin, and later it can be used for comparisons between the different data providers.

Since there is also data that cannot be automatically retrieved through sensors (e.g., years of school, early retirement, etc.), it was also essential to include a mechanism for integrating self-reported data. For this purpose, the users can access questionnaires in the dashboard, which they can fill in with their responses. These answers are also converted into measurements (e.g., early withdrawal from school can potentially contribute to an increase in the risk of cognitive frailty) to further enhance the calculation of the frailty indexes for the individual.

4.2. Post-Processing of Measurements

To have continuously updated frailty risk scores (which themselves are also treated as measurements) for each subject, we needed to provide to the DSS a live feed from a set of specific parameters. Therefore, whenever a new measurement arrives for a user, which impacts a specific risk value, the calculation must be done with the updated values. For that, we included suitable methods on the API/SDK related to this usage scenario to (i) easily subscribe for updates on the desired topic measurements, and (ii) upon the arrival of new measurements, to re-calculate the risk values for that user, injecting back in the appropriate topic the new value of frailty risk. The users themselves can later check what their risk score is on a dedicated interface (further detailed in Section 4.5.2).

Besides these characteristics, some of the measurements can be associated with goals that are defined by the users. A user can check on the dashboard what the measurements are that can be associated with a specific goal. Furthermore, it can set the value for the goal, and whenever the goal is reached, the user is notified of this accomplishment.

These notifications can be sent to a mobile dashboard app running in Android, to a web version of the dashboard, or to a list of messages like a mailbox. An example of such goals is the measurements associated with physical activity in which the user defines a minimum number of steps per day or week. The user can then check his progress and get motivated to reach the goal, also improving in this way his overall physical health.

4.3. Possibility to Share the Data with a Clinician

To increase the quality of life of the subjects participating in the study, the clinicians must be closely monitoring their subjects’ data. To ease this task for both clinicians and patients, we created mechanisms to make this possible. To do so, a clinician can send a request to a subject to follow his data, and once the subject accepts such requests, the clinician can visualise the data being collected by the subject.

With the connection established and the capacity to analyse this data, the clinician can decide if there is a need to recommend the subject to intervention programs that will seek to improve their condition. The subject can see what the clinician recommended and schedule its execution. The clinician also gets the information if the subject performed the recommended intervention and can check the evolution.

4.4. API for Other System Clients

In order for the other parties that do not run directly on the middleware to interact with the user’s data securely, the My-AHA API was enhanced with other methods.

We created methods for the clinicians to assign and manage the assigned interventions for the subjects they are following. Besides this manual assignment of interventions, the DSS is also able to assign them based on the users’ gathered data automatically. On a straightforward scenario, if My-AHA detects lower activity and an increase of physical frailty from a given subject, the DSS can automatically assign an intervention that fosters improvement in physical activity. The DSS, as already described, runs more complex scenarios by analysing the users’ data against a set of decision trees and deciding the need whether or not to assign interventions.

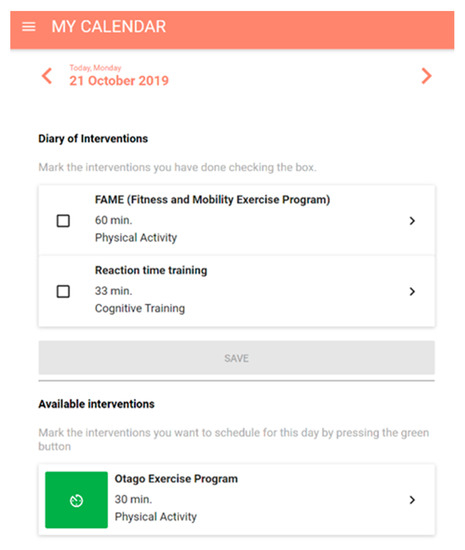

Since not all the interventions can be automatically tracked (e.g., specific exercise programs such as OTAGO home-based exercise program [44] or FAME (Fitness and Mobility Exercise Program) [45]), users have an interface similar to a calendar where they can register whether the assigned intervention was performed. Later, a clinician can check that calendar and, based on the user report, analyse the impact of such interventions on the user frailty data, and consequently on their quality of life. Section 4.5.4 will further detail a practical implementation of this calendar function.

There are also methods to allow access to anonymised data, which can be used for statistical analysis, group comparisons, or research in general. This data can be requested per user, measurement, intervention domain, or trial site.

The middleware included a separate endpoint where the high scores for some of the metrics are stored to ease group comparison between users or even trial centres. Section 4.6 includes an example of the usage of these high scores.

4.5. My Personal Dashboard

As aforementioned, the My Personal Dashboard has been designed to provide a unifying layer to users, over the single platforms and organisations, for providing a coherent and integrated understanding and experience of the My-AHA system as a whole.

The web interface accessible here [46] was tested with the foremost recent browsers both on the PC and on smartphones. To foster its accessibility, the responsiveness of the interface was one of the main drivers of its development so the interface will adapt accordingly with the devices used to guarantee excellent user experience.

Due to practical reasons, the dashboard is also available through an Android application, downloadable from Google Play Store [47].

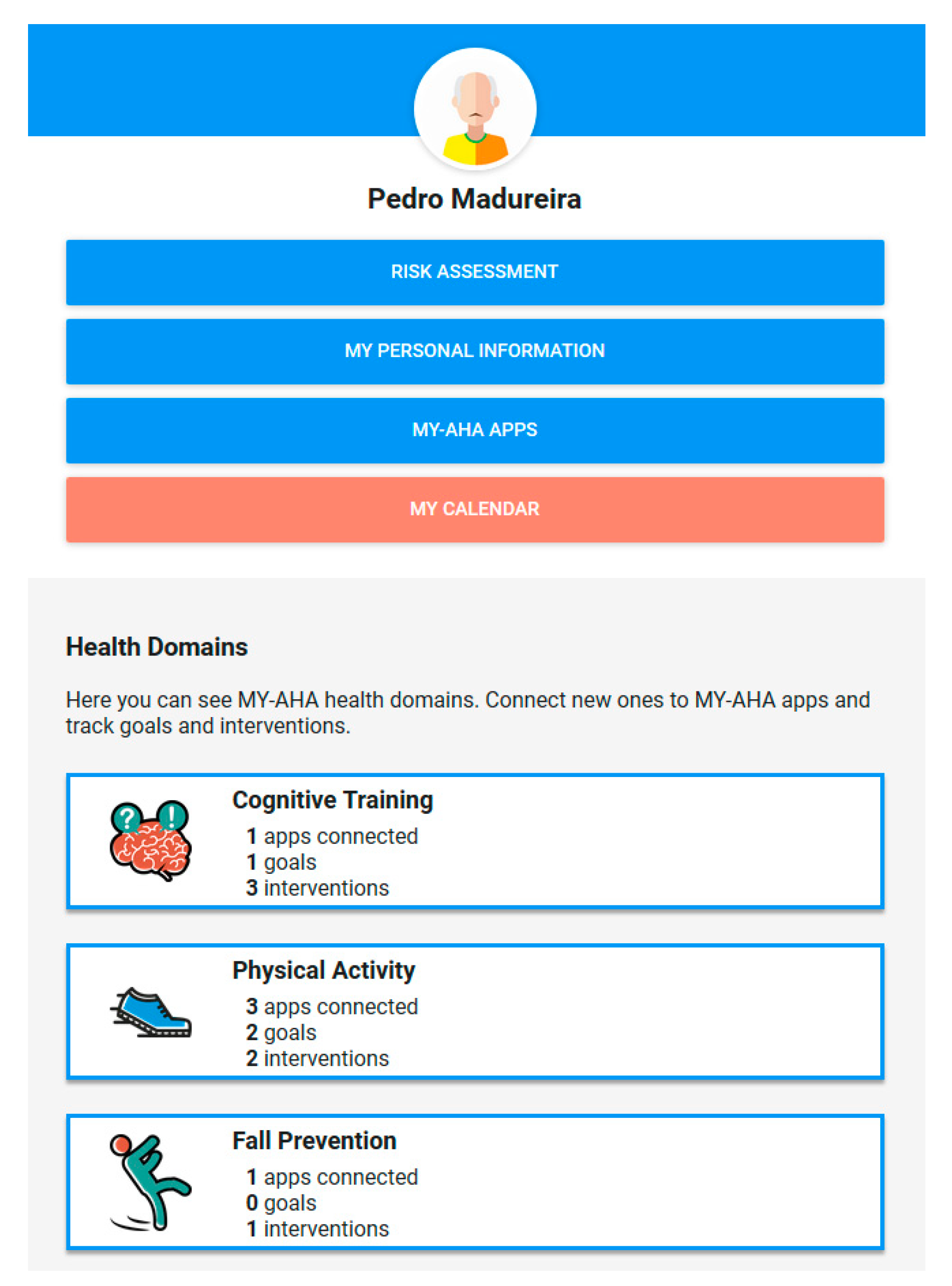

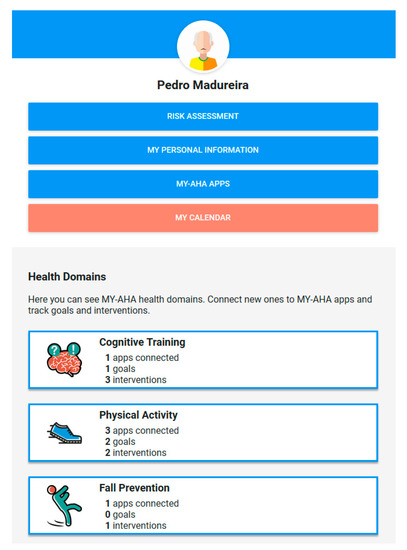

Figure 4 shows the dashboard home screen alongside four of its main sections:

Figure 4.

Dashboard home screen.

- Risk Assessment

- My personal information

- My-AHA apps

- My calendar

In the following sub-sections, a short description of each function and its connection with My-AHA middleware is provided.

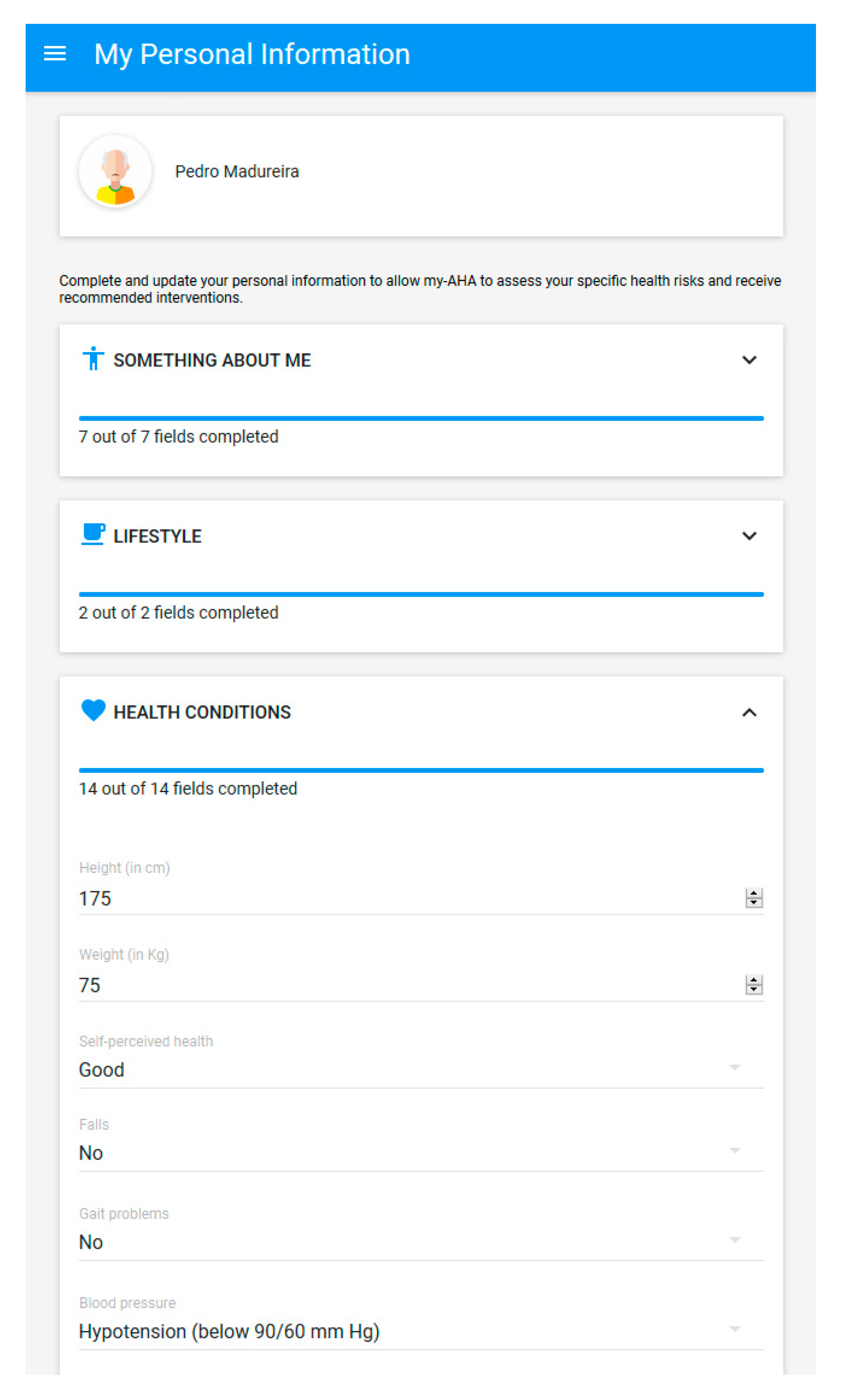

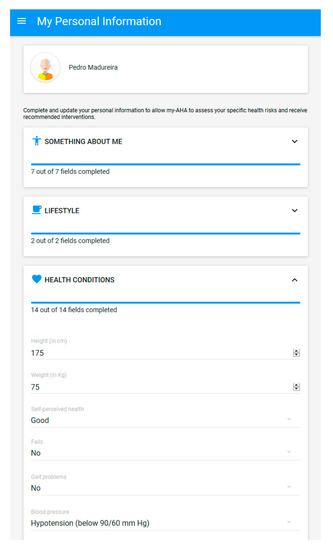

4.5.1. My Personal Information

The screen “My personal information” (shown in Figure 5) can be used by the elderly to provide more details about themselves by displaying data that could not be automatically acquired from sensors or external platforms. Since this data cannot be automatically retrieved, the filling of this data in the dashboard has major importance for the system, so the users are encouraged to fill it upon registering on the platform. Only after the filling of this data can the system provide some of the personalised risk values and get to know the users better in order to give them more personalised advice.

Figure 5.

My Personal Information screen.

The information is categorised into different sections (for a total of 23 questions):

- Something about me (General personal data) (e.g., education, employment, living area)

- Lifestyle (Habits) (e.g., daily alcohol consumptions, smoking habits)

- Health conditions (e.g., falls, gait problems, cholesterol)

This section is connected to My-AHA middleware both for retrieving the data stored and for updating the related personal information.

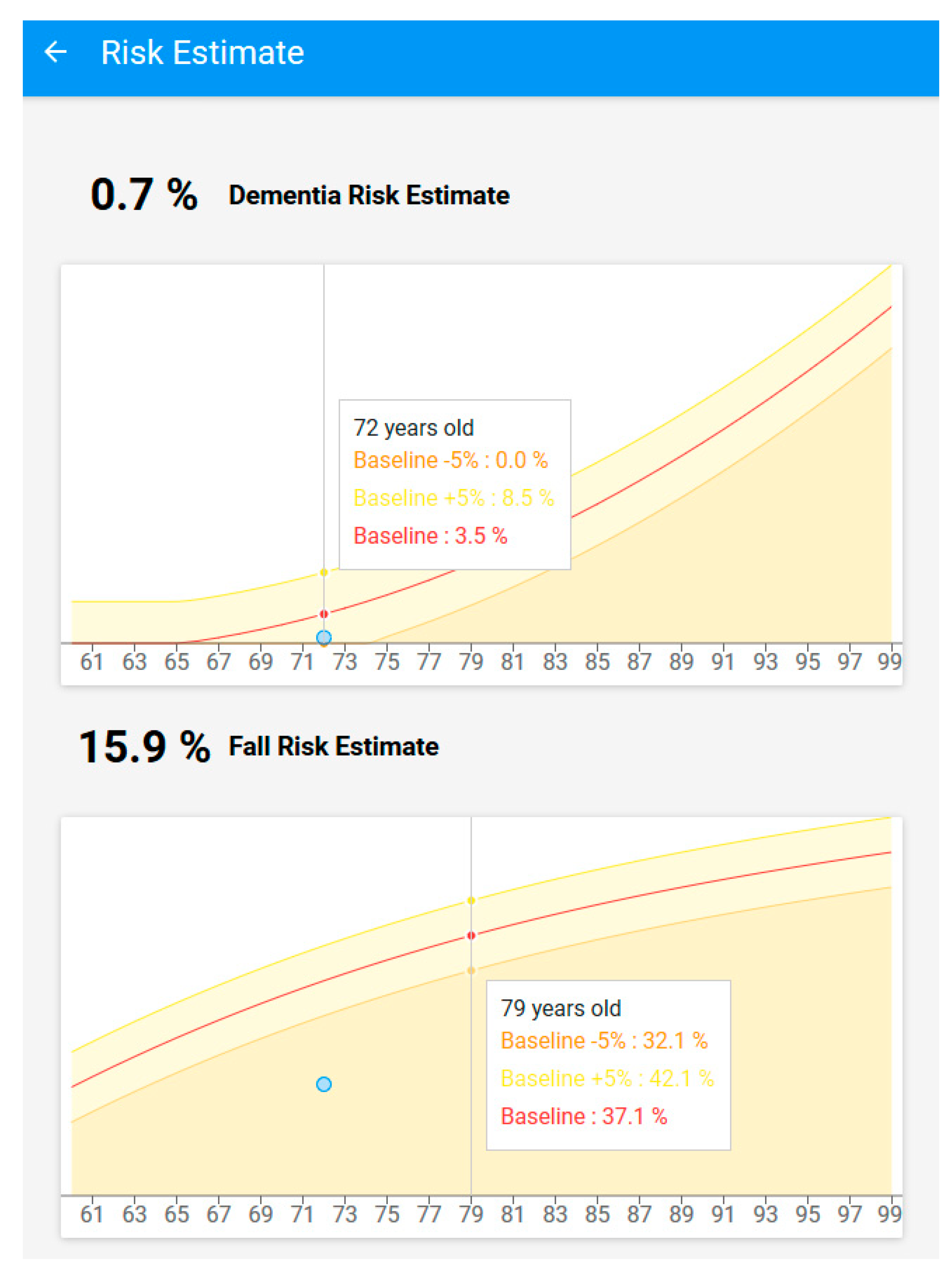

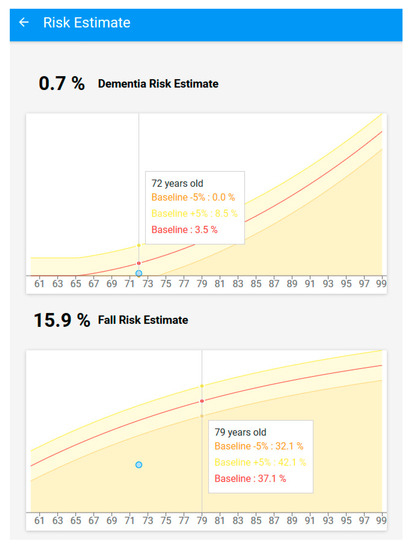

4.5.2. Risk Assessment

When the user enters this section of the dashboard, is shown the overall probability of developing frailty symptoms in different domains: cognitive, physical, emotional, and social. Then, the user can select the result of each domain to see more detailed information. The risk is represented in a plot and shows how the user’s risk is in comparison with the average profile of older people, depending on their age. The risks, as mentioned in Section 3.2, are calculated from a subset of metrics, provided by the user to the system.

The “Risk Assessment” functionality directly gathers the data by My-AHA database. The updated personal information, the continuous monitoring of health parameters, and the results of the intervention plans have been regularly analysed by my-AHA DSS that provides the updated risk assessments for the users.

Figure 6 shows an example of the estimations for dementia and fall risks for a fictitious user. In both cases, the user estimated risk (represented by the blue circle) is slightly below the baseline for the user’s age (represented by the red line), but inside the −5/+5% baseline’s range. The user can see the estimated evolution of the risk values with the age if he does not change any behaviours.

Figure 6.

Risk Values example.

One crucial educational aspect of fostering the self-care of the users is that information is also given on what the metrics are (risk factors) that impact each risk value. So, the user can better understand what can be changed in order to reduce the risks. It is also possible to simulate the outcome of risk values if some of the factors would change. For example, the effects of bodyweight reduction on the risk values can be identified.

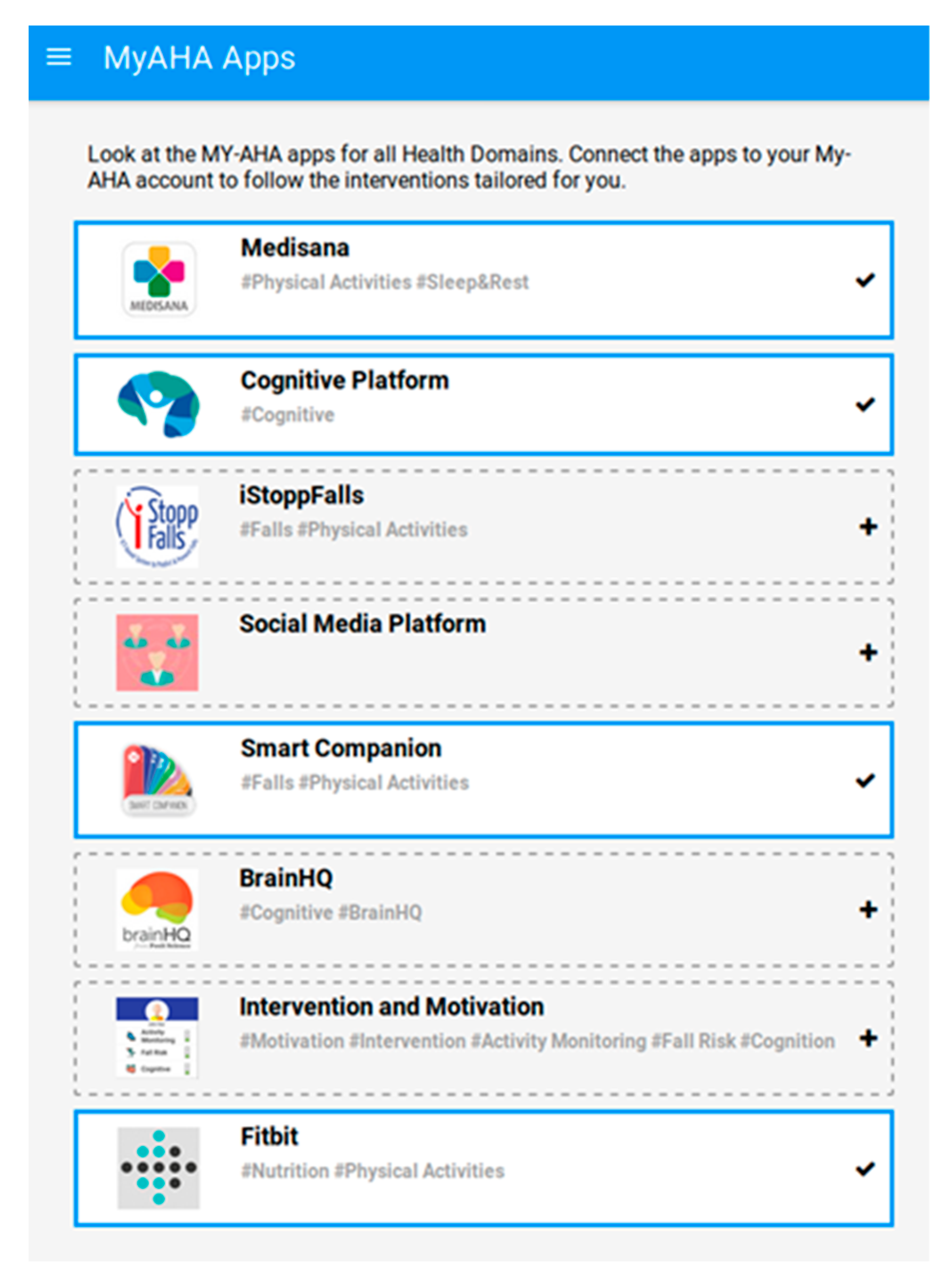

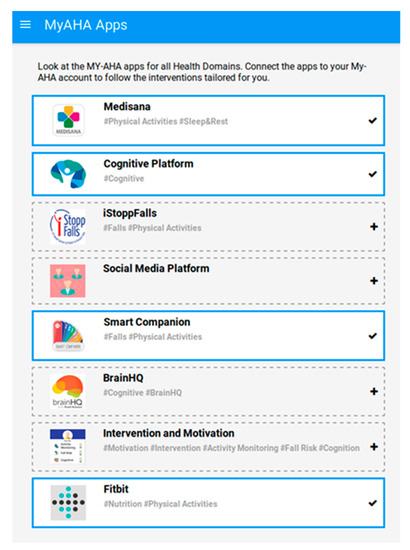

4.5.3. My-AHA Apps

The “My-AHA Apps”, as shown in Figure 7, presents the list of external platforms (independent of My-AHA) to which the middleware has a connection (the connectors mentioned above). These platforms grant the middleware access to user’s data. With that feed, the risk values algorithms on multiple domains, making it possible for the users to obtain interventions provided by other parties.

Figure 7.

My-AHA apps interface.

To use those apps, one must have to be previously registered in the original platforms. After that, to connect My-AHA with the user’s profile in another platform, one must click the platform icon and go through the platform’s authentication procedure and grant access to their data. The middleware stores only the authentication tokens provided by the platform and with this can perform automated further data queries to the platforms on behalf of the user in order to regularly gather the updated data.

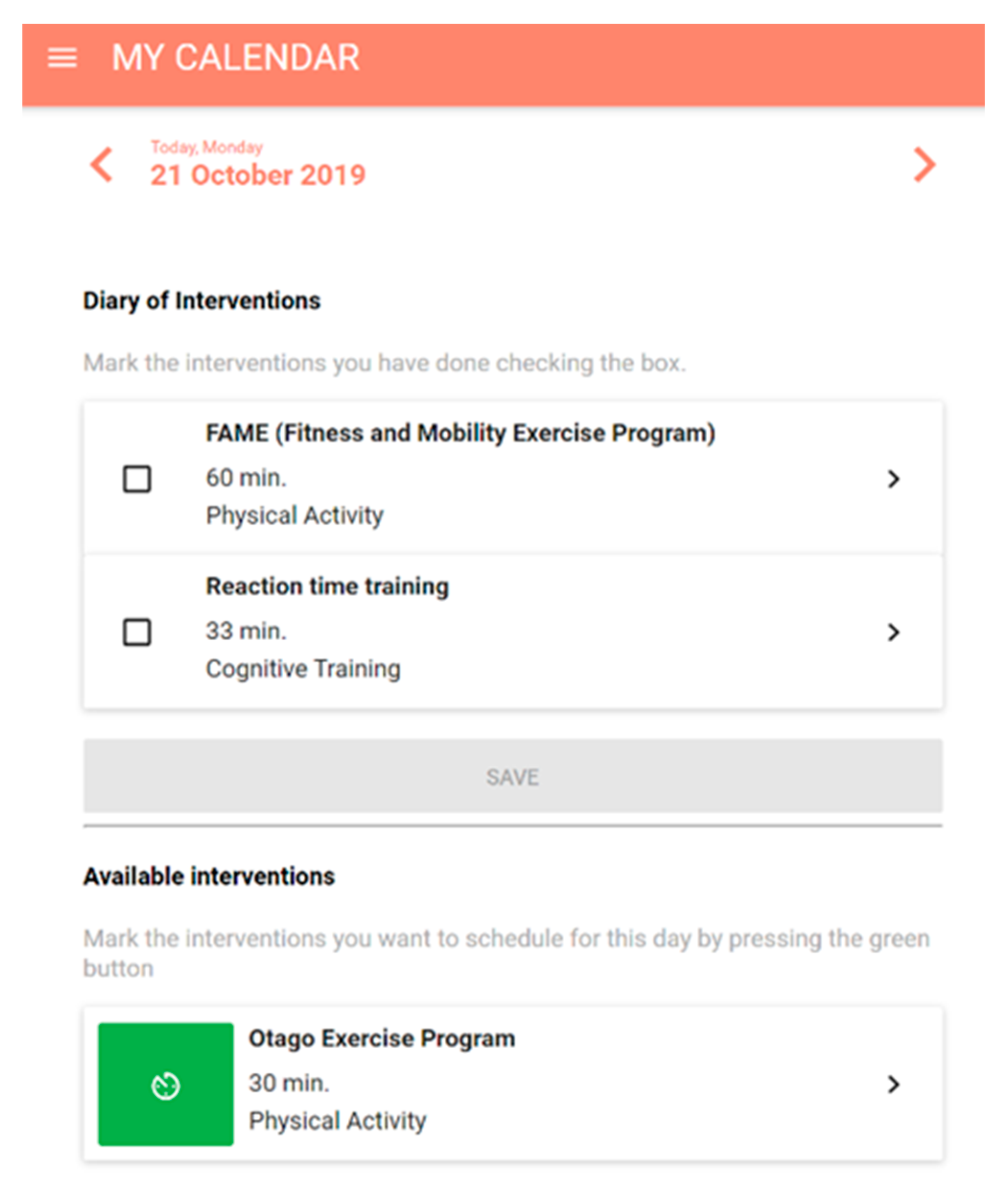

4.5.4. My-Calendar

My-Calendar is the tool that allows the user to keep track of the interventions assigned to them, either automatically by the DSS algorithms or by a clinician. The user can also plan when to perform such interventions (e.g., perform a specific exercise program) and mark them when done. This process is required when automatically tracking such intervention is not possible through the external platforms connected to the system. Keeping an updated record of the performed interventions is essential to guarantee that the My-AHA system functions efficiently, allowing the health professionals to monitor the user-health evolution and their related risks and suggest the better-personalised interventions for the user.

The calendar section gathers the intervention plan available for the user by the connection with the My-AHA middleware. Once the user completes the intervention scheduled, it must register the activity. In this way, the My-AHA middleware and the My-AHA DSS can track the performed intervention, and also gather aggregated data on the user’s adherence to the intervention plan.

Strictly related to my-Calendar function, the Intervention section, available for each domain of My-AHA system, can show the interventions assigned to the user. Figure 8 shows an example of this interface where it is possible to check that the user had planned for the selected day the interventions “FAME Exercise Program” and “Reaction time training” and are pending confirmation that has been performed. Additionally, this user could also schedule the “OTAGO Exercise Program” intervention.

Figure 8.

My-Calendar interface.

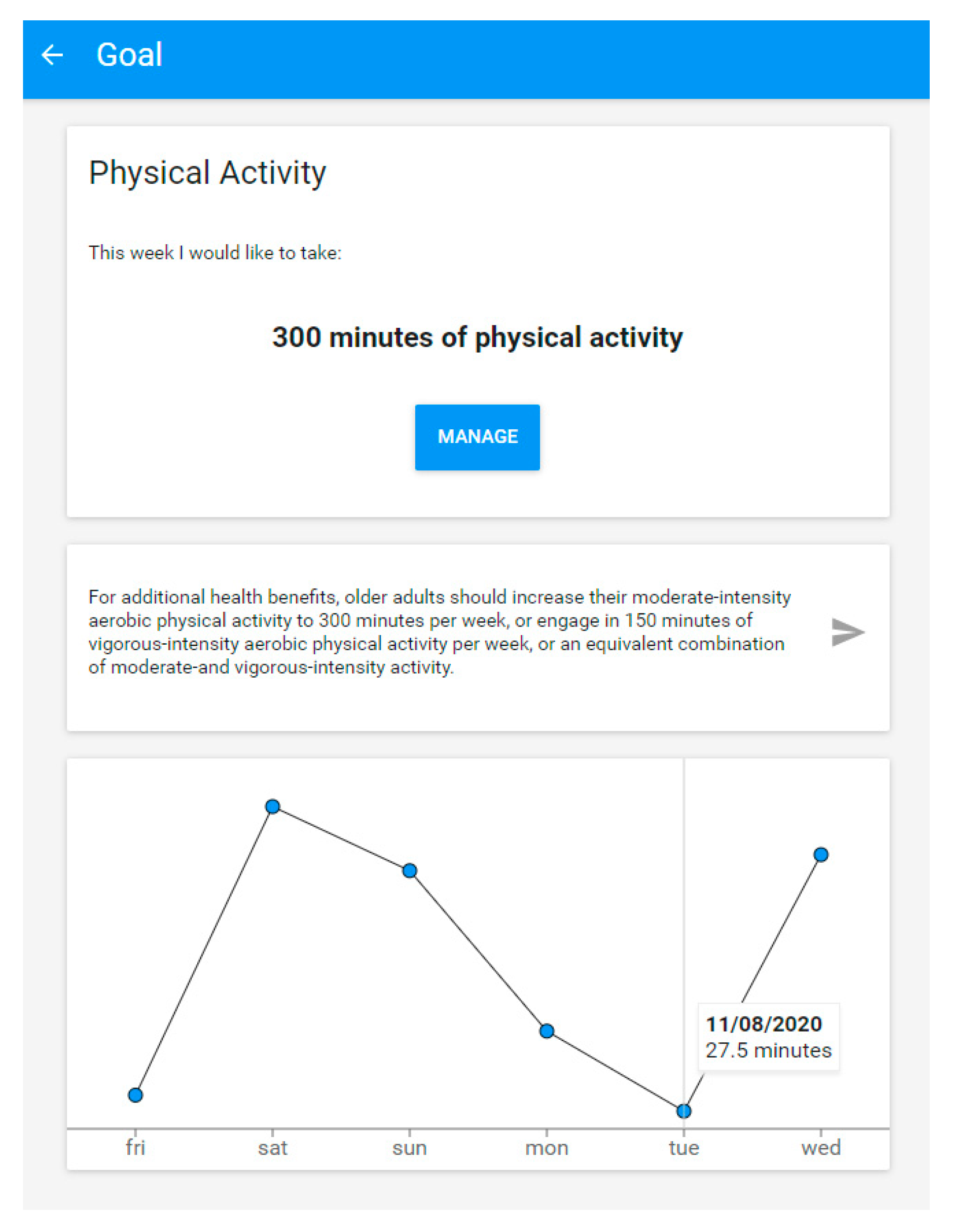

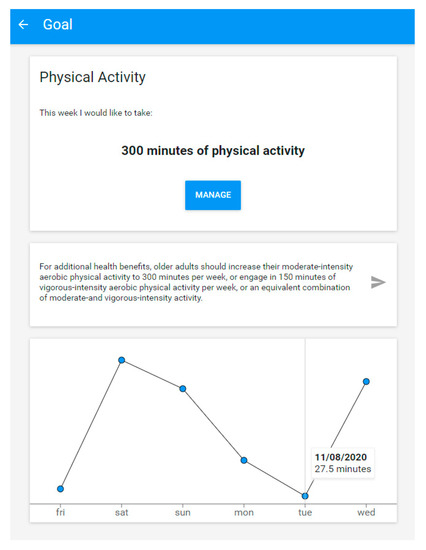

4.5.5. Goals

With the purpose of increasing users’ engagement with the My-AHA platform and fostering positive changes in their daily life routines, we introduced a Goals section inside My Personal Dashboard. This section comprises a simple interface that consists of a chart displaying the participant aggregated data for the last 7 days of a given data parameter (or an aggregation of parameters) and a button which allows the participant to customize its goal on the current domain for regular adjustments.

Figure 9 shows an example of the goals screen for the domain of physical activity. The default goal for physical activity follows the World Health Organization guidelines of physical activity for adults aged 65 years or above which recommends at least 150 min of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week [48]. The user can manually increase this default goal to the value it finds accomplishable and is also given the hint that for additional health benefits, the user should increase their moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity to 300 min per week.

Figure 9.

The goals interface.

In the background, the My-AHA platform is computing all the entries of physical activity the participant performed over the last 7 days including walking, running, or biking that were automatically recorded by the external platforms connected to My-AHA and displaying them on the chart.

As a simple gamification feature, upon achieving the defined goal, the participant receives a notification informing of its achievement.

4.6. Interventions and High Scores through the DSS

To reduce, or delay as much as possible, the declines that are linked with frailty, it was decided to include in the system a set of interventions, providing insights to support the process of behavioural change in the subjects and help them improve their quality of life in several areas. These interventions are automatically updated regularly and compromise well-known programs such as the OTAGO home-based exercise program [44], the FAME program [45], and the iStoppFalls exergames [41] for the physical domain and n-back training [49] and CBMT [50] in a gamified way for the cognitive domain. The DSS uses simplistic decision trees to infer if one user should be assigned an intervention plan or not, or maybe tweak some parameters regarding some previous assignments.

Moreover, the DSS is also calculating high scores based on some of the metrics arriving in the middleware. It uses the high scores endpoint inside the middleware API to store the individual user’s high score data (e.g., most steps taken in a day). This allows us, for example, to obtain a current value of a high score of a given metric which can be used to compare within the test centre which users are more engaged in the physical activity tasks, and this way, compare adherence between them. However, this can also be extended to group comparisons. Since the data is tagged with the centre the user belongs to, it is possible to create a comparison between groups.

With this data, motivational programs can be created, in a gamified way, to motivate users to follow the assigned interventions.

4.7. Living Lab Methodology

A living lab methodology has been applied throughout the project. The new developments were constantly being delivered for a closed set of users, which already have experience with this close involvement with industry or research developments on real-world evaluation process and iterative design/development. This allowed for short iteration processes of development and feedback.

Three settings have been settled for the Living Lab activities. Table 1 summarizes the settings (in Germany), providing more detail of their locations, the number of participants, their living condition, and also the activities they were performing.

Table 1.

Living Lab settings, their users’ living conditions, and their activities.

Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary users have been engaged either for participatory design of the platforms and of the services to be delivered for evaluating the proposed solutions.

After the end of the preliminary testing phase, named Alpha wave, about 20 participants took part in a study phase to investigate usage indicators of the current My-AHA prototype and to design new changes in the technologies for the incoming Randomised Control Trial (RCT).

Our data suggested that the participants in our study experienced enhanced levels of social collaboration and that the group-based activities had a positive impact on the motivation to continually use the My-AHA components. By integrating the My-AHA components, as well as combining technical learning sessions and physical sports courses into their daily lives and routines, participants in the study found that the relationships between them had been strengthened. The results also demonstrate clear social effects, with the system standing as a resource for certain kinds of social responsibility and social interaction to be fostered by our participants.

The main outcome of My-AHA Living Labs is that the combination of ICT plus social activities is key for older adults (domain of active & healthy ageing). This guarantees a good user experience and sustainable use and long-term acceptance.

4.8. Evaluation

My-AHA underwent an initial testing phase with users with constant and close follow-up by the caregivers during a period of 6 months following the living lab methodology described in Section 4.7. That period allowed for an early evaluation of some of the initial assumptions on the technology developed. During that period, due to external and unforeseen circumstances, we were forced to replace one of the external platforms interfacing with My-AHA that was providing nutritional data. It was at that time that the connection with Fitbit was introduced to the system. This update allowed us not only to have an alternative source of data but also to prove within a real scenario the modularity and robustness of the whole software platform that allowed us to replace a data provider in a simplified way, having only to deal with the particularities of the authentication and querying of the new platform without having to change any structure of our system from that point onwards.

This initial phase allowed us also to listen to feedback from the caregivers working more closely with the participants. It was from this feedback arose the idea arose of the goals presented in Section 4.5.5. Upon implementing it, the caregivers noticed a renewed interest in the platform from the participants with the objective of achieving their self-set goals. Furthermore, another important feedback that has been gathered and treated after this first validation has concerned the possibility to schedule and to keep track of the interventions. For this reason, my-calendar functionality has been designed (see Section 4.5.4).

After this initial testing phase, My-AHA ran a multicentre 18-month RCT [51] that lasted until late 2019. This RCT used the initially developed software platform and was further enhanced on the testing phase as a supporting technology for the whole system. Since the project encompassed partners from different countries, it was decided that also this RCT would include users from Spain, Italy, Austria, Australia, and Japan, totalling around 110 users regularly using the system.

When writing this paper, the users participating in the RCT have already contributed to 606,000 measurements collected by the middleware. Even though the RCT inside the My-AHA project has already been finished, several users are still engaged with the platform. By looking at the systems’ data, it is possible to observe that the whole list of users, which besides the RCT above’s participants, also includes users from the living labs testing phase and development and demonstration users, resulting in a total 390 entries on the database that have already provided a total of 935,000 measurements.

From these numbers, some conclusions can be derived from the RCT. The number of measurements coming from passive solutions (e.g., activity trackers) is significantly higher than the ones from platforms where users need to actively engage to generate data (e.g., food logging through Fitbit), and the later tends to decrease over time. So, for future inclusions of external platforms, the target would be focused on solutions that are able to collect data passively. Also, data coming from the dashboard where the users need to answer it manually (refer to Section 4.5.1) came very infrequently, and most of the users answered it only once upon registration, making it challenging to track the evolution over time of some of the risk values. Some of this data insertion in the platform was indeed automated, like the case of body weight, where the users could manually add their weight via the dashboard but could insert it using a Smart Scale from Medisana platform, making it independent of the manual entry.

Regarding the performance of the middleware, each connector was kept running on an hourly basis throughout the whole RCT. The search for new measurements for each one of the registered users’ connected platforms was tested, totalling at the time of writing roughly 470 individual connector runs per hour (each one of these individual runs including multiple API calls). On average, a complete run of the system lasted approximately 50 s. The complete run goes through all the users, searching for new measurements, storing them, notifying the DSS, performing all the necessary updates and post-processing, and finally storing the updated risk, therefore, giving a considerable margin for the scalability of the system. Even with the increase of users and platforms, from the initial testing phases to the total amount of users in the RCT, the performance of the system kept very stable, increasing our degree of confidence in the robustness of the whole system.

5. Conclusions

We have presented our proposed My-AHA software platform that comprises a software ecosystem designed to seamlessly integrate different health and active ageing solutions, targeting senior well-being. It is a platform for senior health monitoring that targets disease prevention through individualised profiling and personalised recommendations, feedback, and support. Considering the use case of early frailty detection, My-AHA focuses on helping caregivers and the seniors themselves improving their current condition considering changes to cognitive, physical, social, and psychological parameters.

My-AHA differentiates from other solutions by being a very dynamic and modular solution, supporting post-processing of measurements, which allows the implementation of a DSS to calculate the frailty risk scores continuously and the inclusion of a dashboard to provide the users with visual feedback. Its inherent modularity on the middleware enables the addition of new platforms and data sources that can be used by the system as alternative sources of data. The security features allow the user to revoke access to its data and complete anonymisation. Furthermore, future integrations with other external systems either through an API to access data and metrics or through the SDK are facilitated. Moreover, clinicians can assign and manage the assigned interventions for the subjects.

In the future, we plan to test My-AHA in a use case to assist clinical trials and to expand further the tracking of transactions using distributed ledger technologies. Also, further research in order to increase user’s adherence to the solution will be performed, either by the integrations of more sources to automate data collection or by more close engagement with the users. It is also planned in parallel the usage of this software platform for a different use case outside of the health scope. With that, we intend to validate that the solution itself is agnostic of the application scenario.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.M., N.C., F.S., W.M., M.B. and P.G.; methodology, P.M., F.S., W.M. and A.O.-J.; software, P.M., N.C., M.B., P.G.; validation, P.M., N.C., M.B. and P.G.; investigation, P.M., N.C., F.S., W.M., A.O.-J., M.B. and P.G.; resources, F.S. and W.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M., N.C., A.O.-J., M.B. and P.G.; writing—review and editing, P.M., N.C., F.S., W.M., A.O.-J., M.B. and P.G.; supervision, F.S., A.O.-J. and W.M.; project administration, P.M.; funding acquisition, F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The European Union supported this work through the My-AHA project (H2020-PHC 21–2015, grant agreement no. 689592).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the whole My-AHA project consortium that directly or indirectly contributed for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Palestra, G.; Rebiai, M.; Courtial, E.; Koutsouris, D. Evaluation of a rehabilitation system for the elderly in a day care center. Information 2018, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C.A.; Collier, R.; O’Hare, G.M.P. A review and classification of assisted living systems. Information 2018, 9, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, L.; Barbarán, J.; Chen, J.; Díaz, M.; Llopis, L.; Rubio, B. Middleware and communication technologies for structural health monitoring of critical infrastructures: A survey. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2018, 56, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Martinez-Martin, E.; Cazorla, M.; Julian, V. PHAROS—PHysical assistant RObot system. Sensors 2018, 18, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhushri, P.; Dzhagaryan, A.; Jovanov, E.; Milenkovic, A. An mHealth tool suite for mobility assessment. Information 2016, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.C.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, S.; Jin, Y.; Baležentis, T. A comprehensive evaluation of the community environment adaptability for elderly people based on the improved TOPSIS. Information 2019, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, J.; Neiterman, E.; Oremus, M.; Lemmon, K.; Stolee, P. Perspectives of older adults, caregivers, and healthcare providers on frailty screening: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- My Active and Healthy Ageing. Available online: http://www.activeageing.unito.it/ (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Madureira, P.; Cardoso, N.; Sousa, F.; Moreira, W. My-AHA: Middleware Platform to Sustain Active and Healthy Ageing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications, Barcelona, Spain, 21–23 October 2019; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, M.; Khera, S.; Dabravolskaj, J.; Garrison, M.; King, S. Identification of Frailty in Primary Care: Feasibility and Acceptability of Recommended Case Finding Tools within a Primary Care Integrated Seniors’ Program. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2019, 5, 233372141984815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardini, F.; Luperto, M.; Romeo, M.; Renoux, J.; Basilico, N.; Krpic, A.; Borghese, N.A.; Ferrante, S. The movecare project: Home-based monitoring of frailty. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics, BHI 2019—Proceedings, Chicago, IL, USA, 19–22 May 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]