Abstract

To overcome the data sparseness in word embedding trained in low-resource languages, we propose a punctuation and parallel corpus based word embedding model. In particular, we generate the global word-pair co-occurrence matrix with the punctuation-based distance attenuation function, and integrate it with the intermediate word vectors generated from the small-scale bilingual parallel corpus to train word embedding. Experimental results show that compared with several widely used baseline models such as GloVe and Word2vec, our model improves the performance of word embedding for low-resource language significantly. Trained on the restricted-scale English-Chinese corpus, our model has improved by 0.71 percentage points in the word analogy task, and achieved the best results in all of the word similarity tasks.

1. Introduction

Recently, textual data are mainly represented in the vector form: one-hot representation [1] and distributed representation [2]. One-hot representation is a very simple way of counting the total number of the whole words appeared in the text as N. Then each word is represented as a vector of length N, with an element value of “1” corresponding to the target word ID and “0” for the rest. Obviously, there is little syntactic or semantic information contained in vectors. At the same time, the sparsity and high-dimension of data lead to huge computing overhead in the processing of massive data. Distributed representation maps the attribute features of words into a set of consecutive dense real vectors discretely, which commonly referred as word embedding. Word embedding is easier for computer recognition, and is usually used in conjunction with distribution theory (words with the same context will have the same or similar semantic relationship) for semantic relation mining, since it contains some grammar and semantic information of the vocabulary. Therefore, word embedding is widely utilized in research fields such as data mining, machine translation, automatic question and answer, and information extraction.

At present, there are two types of word embedding models based on distributed theory, one is based on the method of co-occurring statistical information of word pairs [3], and the other is based on the method of neural network language model [4]. Methods based on word-pair co-occurrence information could not avoid the problems of huge vector dimensions and severe data sparsity. Therefore, researchers proposed several ways to reduce the dimension of the vector space and generate dense low-dimensional continuous word vectors, such as LSA [5], SVD [6] or LDA [7]. Furthermore, GloVe [8] captured semantic analogy information according to the co-occurrence probability of word pairs, and presented the model based on global matrix decomposition. Meanwhile, there is a more widely used word embedding model derived from the neural network model, which is first proposed by Bengio et al. [9] in 2003. Due to the low-efficiency training process of neural network language model (NNLM), Mikolov et al. [10] proposed Word2vec, an efficient open-source word embedding tool, by simplified the N-gram neural network model.

Both Word2vec and GloVe can satisfy the basic needs of simple tasks in natural language processing, such as word analogy and word similarity tasks, but perform poorly in the tasks that are oriented to special conditions and fields. There are two ways to improve the performance of word embedding. One is to extract and combine more features from the context, such as morphological features [11], dependency structures [12], knowledge base [13], semantic relations [14]. The other is to combine the language model of large-scale corpus trained from the neural network, such as ELMo [15], GPT [16], Bert [17], XLM [18]. Both the two ways improve the semantic expression of word embedding significantly, yet they need much more extra-resources, including but not limited to the corpus, encyclopedia dictionaries, semantic networks, morphology and dependency syntax analysis tools, and GPU servers. Unfortunately, none of these resources is easily available that it limits the improvement of low-resource language word embedding.

In this paper, we optimize the word embedding model for low-resource languages based on the intra-sentence punctuations and an easy-to-obtain bilingual parallel corpus. We first generate the global word-pair co-occurrence matrix, as well as reconstruct GloVe, according to the punctuation-based distance attenuation that is based on the features of punctuation and relative distance. Then, get the intermediate vectors of target language from the word alignment probability and intermediate vectors of parallel language trained with GIZA++ and reconstructed GloVe separately on the bilingual parallel corpus. Finally, constructing the low-resource word embedding model, which is constructed with the global word-pair co-occurrence matrix, the intermediate vectors of target language and the models form Word2vec. Experimental results show that our model effectively improves the word embedding performance for low-resource languages with limited additional resources.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 is the related works, and Section 3 details the specific theories and processes involved in our model. In Section 4, we evaluate and analyze the performance of the word embedding model with two different tasks. Finally, Section 5 is about the conclusion and further improvements for this work.

2. Related Works

2.1. Word Embeddings for Low-Resource Languages

Generally speaking, the performance of the word embedding model is mainly determined by the following aspects, including the scale of training corpus, the mining of inner contextual semantic information and the usage of external knowledge. Recently, the optimizations for low-resource languages are usually carried out from the latter two aspects, because of the inherent shortage of resources limits the effectiveness and practicability of most methods.

Chao Jiang et al. [19] argued that the zero entries in the word co-occurrence matrix constructed from low-scale language could provide valuable information for training word embedding, especially when the co-occurrence matrix is very sparse. They proposed a positive-unlabeled learning approach to factorize the co-occurrence matrix and improved the performance compared with GloVe.

Gemma et al. [20] introduced a fast and efficient word embedding model with the weighted graph from word association norms (WAN). Although this model works well for the low-resource language, building WAN is still a difficult and time-consuming task.

Mikel et al. [21] summarized and proposed a robust self-learning method based on the cross-lingual corpus. First, pre-training the monolingual word embedding for each language with frequently used models. Then mapping them into a public space for adversarial learning to optimize the low-resource language with fully trained vectors from rich-resource language. In addition, seed dictionaries can help further improve the performance of low-resource language word embedding.

In this paper, we improve the word embedding model by introducing both inner and external knowledge. Internally, we focus on the impact of punctuation and relative distance on semantic relevance. Externally, we introduce the bilingual parallel corpus for semantic expansion.

2.2. Applications of Punctuations in Natual Language Processing

Punctuations have important applications in natural language processing. They can be used directly for sentence segmentation in tasks related to text processing and play a more critical role in punctuation prediction and text analysis tasks.

Punctuation prediction refers to the recovery or prediction of punctuation marks in a text generation task, usually closely related to sentence boundary detection. As in automatic speech recognition, lack of punctuation can lead to ambiguity problems and confuses both the human reading comprehension and subsequent natural language processing applications (e.g., semantic analysis, automated question and answer, machine translation, etc.). Currently, punctuation prediction methods mainly focus on deep and convolutional neural network models [22] combined with prosodic, acoustic and, lexical features.

Punctuation-aware decoding that works with parsing models can also improve unsupervised dependency parsing [23]. In sentiment analysis, punctuations are important for sentence segmentation and emotional tone judgment, especially in short web text. First, negative words combined with the subsequent punctuation can add negative labels to words between them when dealing with negative sentences [24]. In addition, punctuations such as “!” and “?” can help determine the mood intensity of the current sentence [25].

However, most of the current word embedding models pay little attention to punctuations and even filter out punctuations during the data pre-processing phase. Because there are large enough corpora for training, this defect does not affect high-resource languages, but causes serious waste of semantic information for low-resource languages. Therefore, we focus on the punctuation-based semantic balance mechanism to optimize the word embedding model for low-resource languages.

2.3. GIZA++ Word Alignment

Word alignment is a key step in the statistical machine translation system, which mainly implements word correspondence between source and target languages, and supports the follow-up processes such as phrase extraction, phrase table construction and decoding.

Relatively speaking, the small-scale parallel corpus is an easy-to-obtain resource for resource- scarce languages. So in this paper, we align the word pairs and acquire the word alignment probability with GIZA++ [26], which is an extension of GIZA (an integral part of the statistical machine translation toolkit EGYPT). The aligned parallel words are consistent in semantics with the source word according to the theory of IBM Model 3. Therefore, we regard the aligned parallel words as the semantic extension context of source word, and introduce them into the word embedding training process together.

2.4. Word-Pair Co-Occurrence Matrix

The general construction of a word-pair co-occurrence matrix is as follows:

Given a certain size of training corpus C, and construct the corresponding vocabulary V. N is the size of table V, L is the size of sliding context window. The window orientation is bilateral (left, right or bilateral). If , . Element in the word-pair co-occurrence matrix represents the co-occurrence frequency between the key word and its contextual words in the global corpus C.

The word-pair co-occurrence matrix is a basic but important feature function of statistic-based word vector models. In general, the original matrix has large-scale dimensions and sparse data, which obviously affects the computational efficiency. In order to reduce the matrix dimension and generate continuous real word vectors, statistical models based on the singular value decomposition (SVD) theory had been widely used until GloVe was proposed.

For a word and its contextual words and , represents the probability that appears in the context of throughout the corpus C when . As we can see, when is related to but unrelated to , , on the contrary, , and if is related or unrelated to both and , . From these correspondences, we can train out word vectors from the analogy between the semantic relationship of words and the ratio of word-pair co-occurrence probability.

Therefore, we can analogize the relationship between semantic relation of words and the proportion of word-pair co-occurrence probability, and then present the approximate relationship between word vectors and co-occurrence matrix. In addition, GloVe uses a random gradient descent algorithm to simplify the training process, further improving the computational efficiency. Formula (1) is the loss function and Formula (2) is the weight function.

The word-pair co-occurrence matrix in GloVe is a global statistical probability matrix extracted from the monolingual corpus, which is important and easily available for resource-scarce languages.

2.5. Neural Network Word Embedding Models

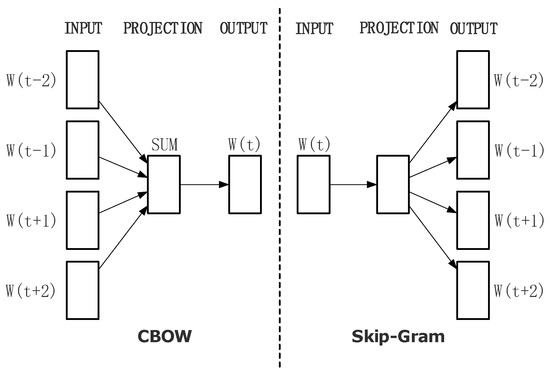

Word2vec contains two word embedding models, as shown in Figure 1. The continuous bag-of-words model (CBOW) aims to predict the current word from contextual words, while Skip-gram predicts the contextual words from current word. In order to improve training efficiency, there are two different accelerate algorithms, namely hierarchical soft-max and negative samples (NEG). Essentially, hierarchical soft-max algorithm is a continuous classification problem based on Huffman theory. It optimizes the traditional soft-max algorithm and avoids the all-words probability calculation for each iteration. The training efficiency is greatly improved, and the time complexity is reduced from to . NEG is a simplified algorithm of noise contrastive estimation (NCE) [27]. It constructs the training set by weighted negative sampling and balances the distribution of words by subsampling. In general, compared with hierarchical soft-max, NEG is faster because it avoids the circular classification along the inner node path.

Figure 1.

Models of Word2vec.

Word2vec guarantees the performance of the model by training as much corpus as possible in the shortest possible time. It simplifies the models and algorithms by multiple sampling as much as possible to increase the training efficiency and evades the impact of word relative distance on semantic relevance. Therefore, it is not suitable well for resource-scare languages, and we need to refactor its models and algorithms.

3. Word Embedding Model Based on SOP and Parallel Corpus

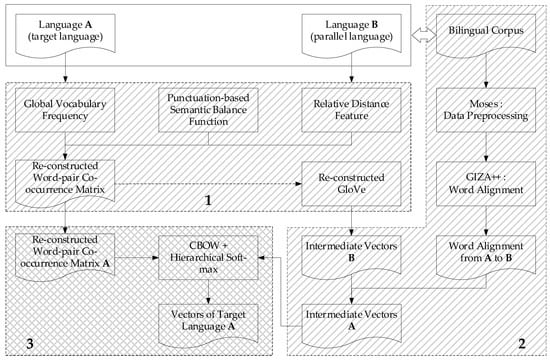

In this section, we present a word embedding model based on semantic obstructing punctuation (SOP) and parallel corpus, which integrates with the punctuation-based semantic balance function, relative distance feature, bilingual alignment information, word-pair co-occurrence matrix, and reconstructed Word2vec model together. Figure 2 shows the training process of this model.

Figure 2.

Training process of word embedding model based on SOP and parallel corpus.

The whole flow diagram is summarized into three main stages that marked with shaded boxes:

- Construct the global word-pair co-occurrence matrix. We integrate with the global vocabulary frequency information, the punctuation-based semantic balance function, and relative distance feature to generate the global word-pair co-occurrence matrix. We also adjust the GloVe model with this re-constructed matrix, and use the optimized model to generate the intermediate vectors in the next stage.

- Generate the bi-lingual based intermediate word embedding. We obtain the word alignment probability from bilingual parallel corpus trained with Moses and GIZA++, and get the intermediate vectors of language B trained with the reconstructed model mentioned in Stage 1. Then we combine the alignment probability with the intermediate vectors B to figure out the intermediate vectors A.

- Refactor the word embedding model. We refer to Word2vec and build the final word embedding model, which combined with the word-pair co-occurrence matrix generated from Stage 1 and the intermediate vectors A from Stage 2. Finally, calculating the word vectors of target language A by using this model.

3.1. Construct the Global Word-Pair Co-Occurrence Matrix

The re-constructed word-pair co-occurrence matrix proposed in this paper is calculated with the SOP-based distance attenuation function.

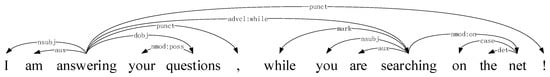

The distance attenuation function is used to determine the relative position feature weight of a word pair in the context window. This weight reflects the semantic relevance between word pairs. Intuitively, the further the distance between words in a sentence, the lower the semantic relationship between them. At present, there are two representative distance attenuation functions, such as in Word2vec and in GloVe, where L is the context window size and is the absolute distance between and . However, due to the grammatical structure and punctuation marks used in the sentences, the simple distance attenuation function does not match the actual semantic relationship satisfactorily. Figure 3 shows the dependency analysis of a sentence, in which the directed arc connection path between the two words indicates the semantic correlation of this word pair. As we can see, the semantic relation of {answering, questions} is closer than {your, questions}, while the former has a longer word spacing than the latter. Meanwhile, {I, questions} is also closer than {questions, while} because of the semantic interrupt caused by punctuation “,”. Both of them show that the simple distance attenuation function used in GloVe or Word2vec does not work well in actual contexts. A direct and effective strategy is to replace the absolute distance with the span in the dependency tree between word pairs. Unfortunately, this approach requires corresponding dependency treebanks or dependency analysis tools, which is time-consuming and labor-intensive for low-resource languages.

Figure 3.

Dependency analysis of a sentence.

In this paper, we define the punctuations within the sentence as semantic obstructing punctuation (SOP) which destroys the contextual semantic coherence of a sentence, such as “,”. In order to get the preliminary assessment of the impact of SOP on semantic information, we count the distribution of punctuation in the novel Don Quixote, and list the results in Table 1. Divide the punctuations into two classifications based on whether they strongly interrupt the semantic continuity of the context: SOP refers to those interrupted and N-SOP refers to the others. Sentences include SOP account for 88.02% of the whole novel, as well as, SOP accounts for 98.45% of the total number of punctuation marks and 12.02% of the total number of words. It can be seen that SOP strongly participates in the representation of sentences, so it is necessary to introduce the punctuation mechanism into the training process of word embedding.

Table 1.

Distribution of punctuation marks in novel: Don Quixote.

According to the researches above, we summarize two hypotheses:

1. The semantic relationship decreases as the distance increases between words in the sentence.

2. There is no semantic relationship between the words distributed on both sides of SOP.

Constructing the SOP-based distance attenuation function:

When there is no SOP exists between words in the sentence, the attenuation coefficient is the reciprocal of the absolute distance. Otherwise, for data smoothing, we use the reciprocal of the maximum window size instead of 0. Taking Figure 1 as an example, setting the context window length . When the keyword is “questions”, the corresponded context is {“I”, “am”, “answering”, “your”, “,”, “while”, “you”, “are”}. According to the original distance attenuation function in GloVe, the distance weights of the word pair (answering, questions) and (while, questions) are both 1/2, which is obviously not correspond to the semantic relationship. Because the comma symbol interrupts the relationship between the word pair (while, questions). Therefore, we adjust the distance weight of word pair (while, questions) by 1/4 according to Formula (3), which is obviously consistent with the real semantic relationship better.

Traverse the whole text and construct the word-pair co-occurrence matrix based on Formula (3) and (4), where represents the number of times and appeared together in a sliding window.

3.2. Generate the Bi-Lingual Based Intermediate Word Embedding

Compared with the dependency treebank and semantic network, small-scale bilingual parallel corpus is a relatively easy-obtained resource, because of the lower linguistic expertise requirements for annotating staff. Therefore, we can optimize the performance of word embedding for low-resource language with the potential semantic information extracted from the bilingual corpus. In this paper, we first clean and normalize the bilingual parallel corpus with Moses and then get the word alignment information trained with GIZA++.

Defining is the monolingual corpus of language A, and is the parallel corpus of languages A and B. We use GIZA++ to align and extract the bidirectional word alignment file , and sort out the word alignment relationship , where word , word and is aligned to A, is the alignment probability between word and .

We can map the sematic information from language B to language A based on the word alignment probability . Replacing the original word-pair co-occurrence matrix in GloVe with the adjusted one mentioned in Section 3.1 to reconstruct the original GloVe model, and training the intermediate word vectors of language B from the parallel corpus . And then generating the intermediate word vectors of language A with the alignment probability and the word-alignment- based vector mapping function shown in Formula (5), where represents the vector of word and represents the vector of word .

3.3. Refactor the Word Embedding Model

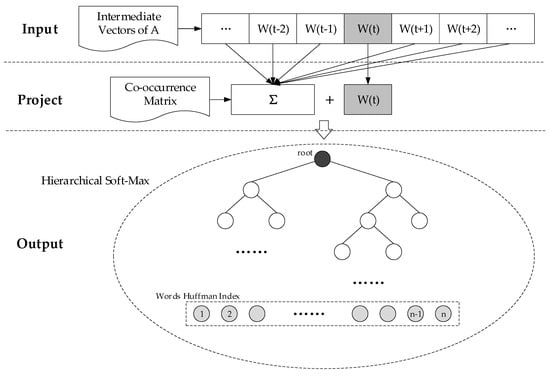

The final word embedding model is combined with the results of the two processes detailed above: the global word-pair co-occurrence matrix constructed by the SOP-based distance attenuation function in Section 3.1, and the intermediate word vectors of language A generated from the word alignment file in Section 3.2. Taking CBOW model and hierarchical soft-max algorithm as examples in Figure 4, the intermediate vectors A are used as the initial values of language A for corpus in the Input Layer. Then, combing the Formulas (2), (3) and (5) to construct the contextual representation function of word in the Project Layer, i.e.,

where the element in word-pair co-occurrence matrix is used as the association weight between words and in the same context window.

Figure 4.

Reconstructed word embedding model.

Finally, taking CBOW and hierarchical soft-max as an example, we used the gradient descent algorithm to calculate and iteratively update the word vectors of language A until the gradient converges and get the final result. In addition, we remove the random sampling process used in the Word2vec, because it limits the semantic extraction for low-resource language despite improving the operating efficiency for rich-resource language.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Corpus, Model and Parameter Settings

In this paper, we take an English-Chinese parallel corpus as the training set, which is consisted with the news of official UN documents, and oral conversations of English learning websites and movie subtitles shared by AI Challenger 2018. To simulate low-resource text, we randomly sample 1M couples of sentences with the sentence length limited to 15 words. We tokenize the Chinese corpus with HIT LTP [28], and extract the word alignment probability with GIZA++.

In order to verify the contributions of the SOP-based distance attenuation function, word-pair co-occurrence matrix and word alignment probability in this paper, we take Word2vec and GloVe as the baseline standard, and construct other three word embedding models: “G+SOP+Distance”, “W+SOP+Distance”, “W+SOP+Distance+Align”. The first model is GloVe with SOP-based distance attenuation function. Compared with Word2vec with no attenuation function used, “W+SOP+ Distance” is combined with SOP-based word-pair co-occurrence matrix only, while “W+SOP+ Distance+Align” is combined with all of the features.

Refer to the prior knowledge in other papers [8], for all of our experiments, we set the word vector dimension as 200, minimum word frequency as 0 or 5, bilateral context, and the slide window size is 5, 8 or 10. For GloVe and “G+SOP+Distance”, we set , , and choose the initial learning rate of 0.05. For Word2vec, “W+SOP+Distance” and “W+SOP+Distance+ Align”, we train the word vectors by use of CBOW and hierarchical soft-max, since they work better when canceling the multiple sampling for small-scale corpus.

4.2. Evaluation Tasks

Evaluation on this work is word analogy task described in Mikolov et al. [29]. The structure of the questions in the task is described as follows: A is to B as C is to _. The data set consists of a semantic subset and a syntactic subset. The answer of this question is predicted by cosine similarity calculation, and will be the only correct result when it is consistent with the word provided from the data set. We also evaluate our models with Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (PCC) on variety of word similarity data sets listed in Table 2: RG [30], MC [31] (subset of RG), WordSim [32], SCWS [33] (with part-of-speech tagging and sentential contexts), RW [34] (for rare words).

Table 2.

Word similarity data sets.

4.3. Results

We present results of word analogy task for all of the 5 models with 2 minimum Min-Count frequencies and 3 window sizes in Table 3. Model “W+SOP+Distance+Align” achieves a total accuracy of 21.30%, better than other models, with window size 5 and Min-Count 5. Meanwhile, both “G+SOP+Distance” and “W+SOP+Distance” have a slight improvement in most cases compared with their original models. The results show significantly that SOP-based distance attenuation function and word alignment probability can effectively improve the performance of word embedding on the small-scale corpus.

Table 3.

Results of word analogy task.

Table 4 shows the results of word similarity tasks. For each model, we get the word vectors with 6 different values of window size and Min-Count, and obtain 6 groups of cosine similarity scores for each word pairs in a certain word similarity data set. Computing the PCC between human judgements and 6 groups of scores separately. Then the item in the table is the average of 6 different PCC values corresponded to each model. As we can see, “W+SOP+Distance+Align” performs overall optimum compared with Word2vec, but lost to GloVe and “G+SOP+Distance” on MC and RG. Considering the number of word pairs in MC and RG in Table 2, the consistency of the lexical distribution between the training corpus and the task sets may be too low since the number of samples is too small, which affects the model performance evaluation. In addition, “W+SOP+Distance +Align” is optimal when “W+SOP+Distance” drags the hind legs, which indicates that the word alignment probability can bring more word similarity information for word embedding.

Table 4.

Results of word similarity task.

5. Conclusions and Future Works

In this paper, we present a low-resource oriented word embedding model learned from Word2vec and GloVe. We focus on the impacts of the punctuation and relative distance on the word-pair co-occurrence matrix, as well as the word alignment information trained from the bilingual parallel corpus with GIZA++. Then, refer to the framework of Word2vec, we integrate the co-occurrence matrix and the word alignment information to reconstruct the final word embedding model. The results evaluated on a small scale of 1 million parallel corpus show that both the SOP-based distance attenuation function and bilingual word alignment information can raise the performance of Word2vec and GloVe effectively. For future works, we will build the relevant test sets for low-resource languages and verify the actual effectiveness of our model in other languages. In addition, considering the cross-lingual word embedding based on adversarial learning can map the semantic information from rich–source language to low-resource language, we will try to improve the performance of our model by replacing word alignment information with cross-lingual transfer knowledge.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y.; Methodology, Y.Y.; Software, Y.Y.; Validation, Y.Y., X.L. and Y.-T.Y.; Investigation, Y.Y.; Resources, X.L. and Y.-T.Y.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; Writing—review and editing, X.L. and Y.-T.Y.; Funding acquisition, Y.-T.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U1703133), The West Light Foundation of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 2017-XBQNXZ-A-005), Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (Grant No. 2017472), The Xinjiang Science and Technology Major Project under (Grant No. 2016A03007-3), The High-level talent introduction project in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Grant No. Y839031201).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Collobert, R.; Weston, J.; Bottou, L.; Karlen, M.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Kuksa, P. Natural language processing (almost) from scratch. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2493–2537. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlgren, M. The Word-Space Model: Using Distributional Analysis to Represent Syntagmatic and Paradigmatic Relations between Words in High-Dimensional Vector Spaces. Ph.D. Thesis, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Turney, P.D.; Pantel, P. From frequency to meaning: Vector space models of semantics. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2010, 37, 141–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, A.; Hinton, G.E. A scalable hierarchical distributed language model. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–10 December 2008; pp. 1081–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Deerwester, S.; Dumais, S.T.; Furnas, G.W.; Landauer, T.K.; Harshman, R. Indexing by latent semantic analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1990, 41, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullinaria, J.A.; Levy, J.P. Extracting semantic representations from word-pair co-occurrence statistics: A computational study. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RRitter, A.; Etzioni, O. A latent dirichlet allocation method for selectional preferences. In Proceedings of the 48th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Uppsala, Sweden, 11–16 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; Manning, C. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y.; Ducharme, R.; Vincent, P.; Jauvin, C. A neural probabilistic language model. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 1137–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolov, T.; Sutskever, I.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.S.; Dean, J. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Stateline, NV, USA, 5–10 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cotterell, R.; Schütze, H. Morphological word-embeddings. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Denver, CO, USA, 31 May–5 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, O.; Goldberg, Y. Dependency-based word embeddings. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Baltimore, MD, USA, 22–27 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Bai, Y.; Bian, J.; Gao, B.; Wang, G.; Liu, X.; Liu, T.-Y. Rc-net: A general framework for incorporating knowledge into word representations. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM International Conference on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Shanghai, China, 3–7 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, H.; Wei, S.; Ling, Z.-H.; Hu, Y. Learning semantic word embeddings based on ordinal knowledge constraints. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Beijing, China, 26–31 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.E.; Neumann, M.; Iyyer, M.; Gardner, M.; Clark, C.; Lee, K.; Zettlemoyer, L. Deep contextualized word representations. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, New Orleans, LA, USA, 1–6 June 2018; pp. 2227–2237. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training. Available online: https://www.cs.ubc.ca/~amuham01/LING530/papers/radford2018improving.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2019).

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Lample, G.; Conneau, A. Cross-lingual Language Model Pretraining. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1901.07291.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2019).

- Jiang, C.; Yu, H.F.; Hsieh, C.J.; Chang, K.W. Learning Word Embeddings for Low-Resource Languages by PU Learning. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1805.03366.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2019).

- Bel-Enguix, G.; Gómez-Adorno, H.; Reyes-Magaña, J.; Sierra, G. Wan2vec: Embeddings learned on word association norms. Semant. Web. 2019, 10, 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artetxe, M.; Labaka, G.; Agirre, E. A Robust Self-Learning Method for Fully Unsupervised Cross-Lingual Mappings of Word Embeddings. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1805.06297.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2019).

- Tilk, O.; Alumäe, T. Bidirectional Recurrent Neural Network with Attention Mechanism for Punctuation Restoration. In Proceedings of the Interspeech, San Francisco, CA, USA, 8–12 September 2016; pp. 3047–3051. [Google Scholar]

- Spitkovsky, V.I.; Alshawi, H.; Jurafsky, D. Punctuation: Making a point in unsupervised dependency parsing. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, Association for Computational Linguistics, Portland, OR, USA, 23–24 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, U.; Mansoor, H.; Nongaillard, A.; Ouzrout, Y.; Qadir, M.A. Negation Handling in Sentiment Analysis at Sentence Level. J. Comput. 2017, 12, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koto, F.; Adriani, M. A comparative study on twitter sentiment analysis: Which features are good? In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Applications of Natural Language to Information Systems, NLDB 2015, Passau, Germany, 17–19 June 2015; pp. 453–457. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Q.; Vogel, S. Parallel implementations of word alignment tool. In Proceedings of the Software Engineering, Testing, and Quality Assurance for Natural Language Processing, Columbus, OH, USA, 19–20 June 2008; pp. 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann, M.U.; Hyvärinen, A. Noise-contrastive estimation of unnormalized statistical models, with applications to natural image statistics. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 307–361. [Google Scholar]

- Che, W.; Li, Z.; Liu, T. Ltp: A Chinese language technology platform. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Computational Linguistics: Demonstrations, Beijing, China, 23–27 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1301.3781.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2019).

- Rubenstein, H.; Goodenough, J.B. Contextual correlates of synonymy. Commun. Acm 1965, 8, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.A.; Charles, W.G. Contextual correlates of semantic similarity. Lang. Cogn. Processes 1991, 6, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, R.L. Placing search in context: The concept revisited. Acm Trans. Inf. Syst. 2002, 20, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.H.; Socher, R.; Manning, C.D.; Ng, A.Y. Improving word representations via global context and multiple word prototypes. In Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Jeju Island, Korea, 8–14 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Luong, T.; Socher, R.; Manning, C. Better word representations with recursive neural networks for morphology. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, Sofia, Bulgaria, 8–9 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).