Visual Analysis Scenarios for Understanding Evolutionary Computational Techniques’ Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Evolutionary Computing

2.2. Estimation-of-Distribution Algorithms

- Initially, a population of N individuals is produced, generally assuming a uniform distribution of variables;

- A number m < N of individuals is then selected from the population by any of the selection methods used in evolutionary algorithms, such as tournament or truncation;

- On the basis of the evaluation of the selected individuals, a better probabilistic model for the variables is set up;

- On the basis of the distribution obtained in the previous step, a new population of N individuals is produced.

2.3. Information Visualization and Visual Analytics

2.3.1. Information Visualization

- Overview: provides the user with general context about all the data that will be analyzed;

- Zoom: allows the user to focus on a certain subset of the data to emphasize the analysis, that is, to analyze a certain context with greater precision;

- Filter: enables the user to reduce the size of the analyzed dataset, limiting the number of items based on the desired criteria;

- Details-On-Demand: provides additional non-visible information and details about a particular item;

- Relate: allows the analysis of the relationship among data items;

- History: keeps a history of actions to support the undo function;

- Extract: allows the extraction of sub-collections of detailed data when needed.

2.3.2. Visual Analytics

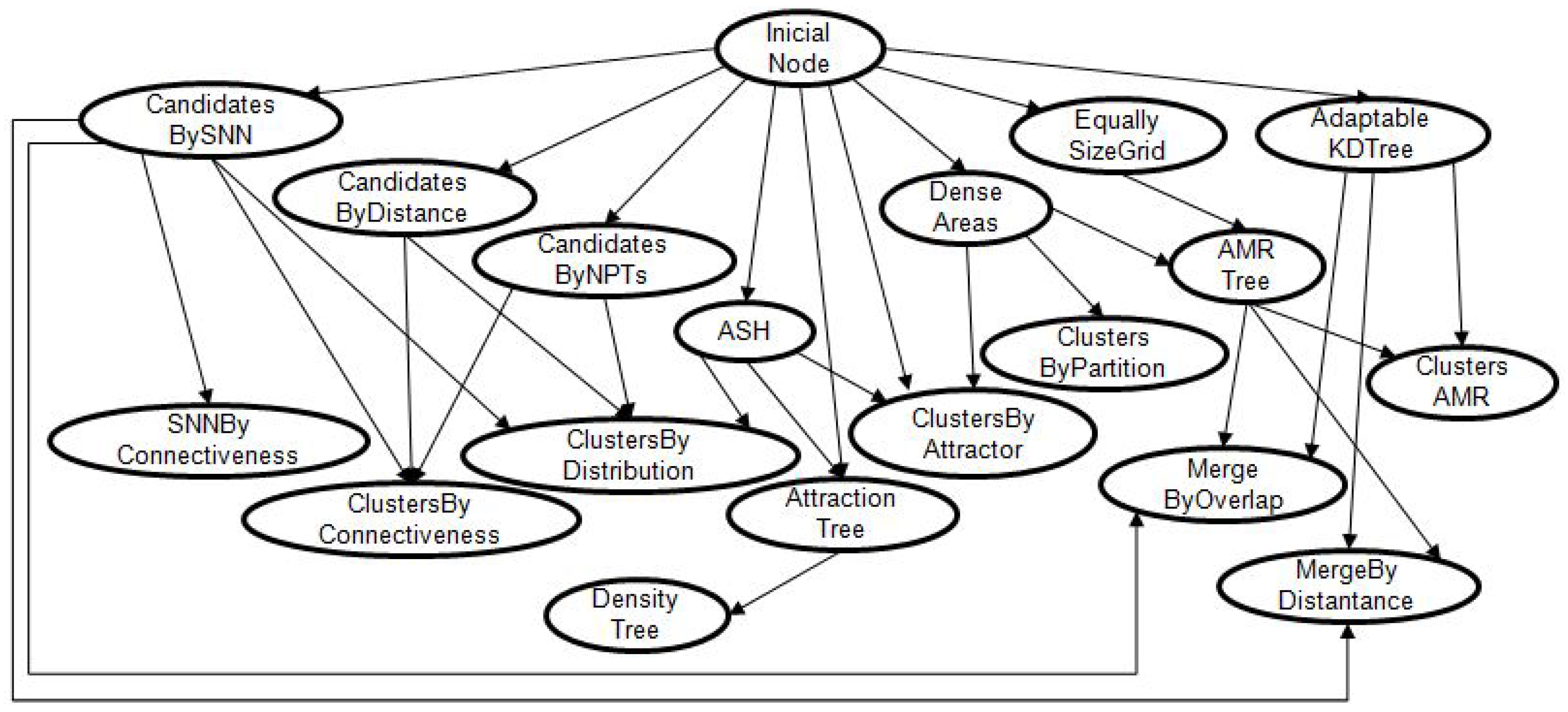

2.4. AutoClustering

- Generate a population of N density-based algorithms. Each individual (or algorithm) represents a possible path in the DAG.

- Use the Clest method to evaluate each individual.

- Eliminate the 50% of individuals with the lowest fitness.

- Update the probabilities of each edge of the DAG according to the frequency of use in the selected population (the 50% of individuals with a higher level of fitness).

- Generate a new population of N individuals using the updated DAG.

- Add the best individual from the previous population to the current one (implementing elitism).

- Repeat steps 2–7.

2.5. Fitness Function

3. Related Work

- Examining individuals and their codifications in detail;

- Tracing the origin and survival of building blocks or partial solutions;

- Tracking ancestral trees;

- Examining the effects of genetic operators;

- Examining the population considering convergence, specialization, etc.;

- Obtaining statistics and trends of the gross population;

- Examining freely in time (generations and rounds) and across populations.

- Visualization of the fitness distribution—scatterplot;

- Visualization of genetic operators—matrix of points;

- Visualization of the genetic lineage of an individual—parallel coordinates, histograms.

4. Visualization Scenarios

- Data overview: these visualizations present the complete dataset and guide the user in further analysis.

- -

- Types of individuals;

- -

- Occurrence of individual types per generation;

- -

- Individuals with the best fitness.

- Tracking: these visualizations present the occurrence of individuals in the population and in each generation.

- -

- Tracking individuals.

- Individual features: these visualizations present the correlation between the individual parameters and allow for the analysis of outliers, trends, and patterns.

- -

- Correlation between fitness and parameters of the individuals per generation and rounds.

- Fitness: these visualizations aim to analyze the fitness in the population per generation and round to understand the evolution and diversity of the population.

- -

- Fitness evolution;

- -

- Average of fitness;

- -

- Variance of fitness.

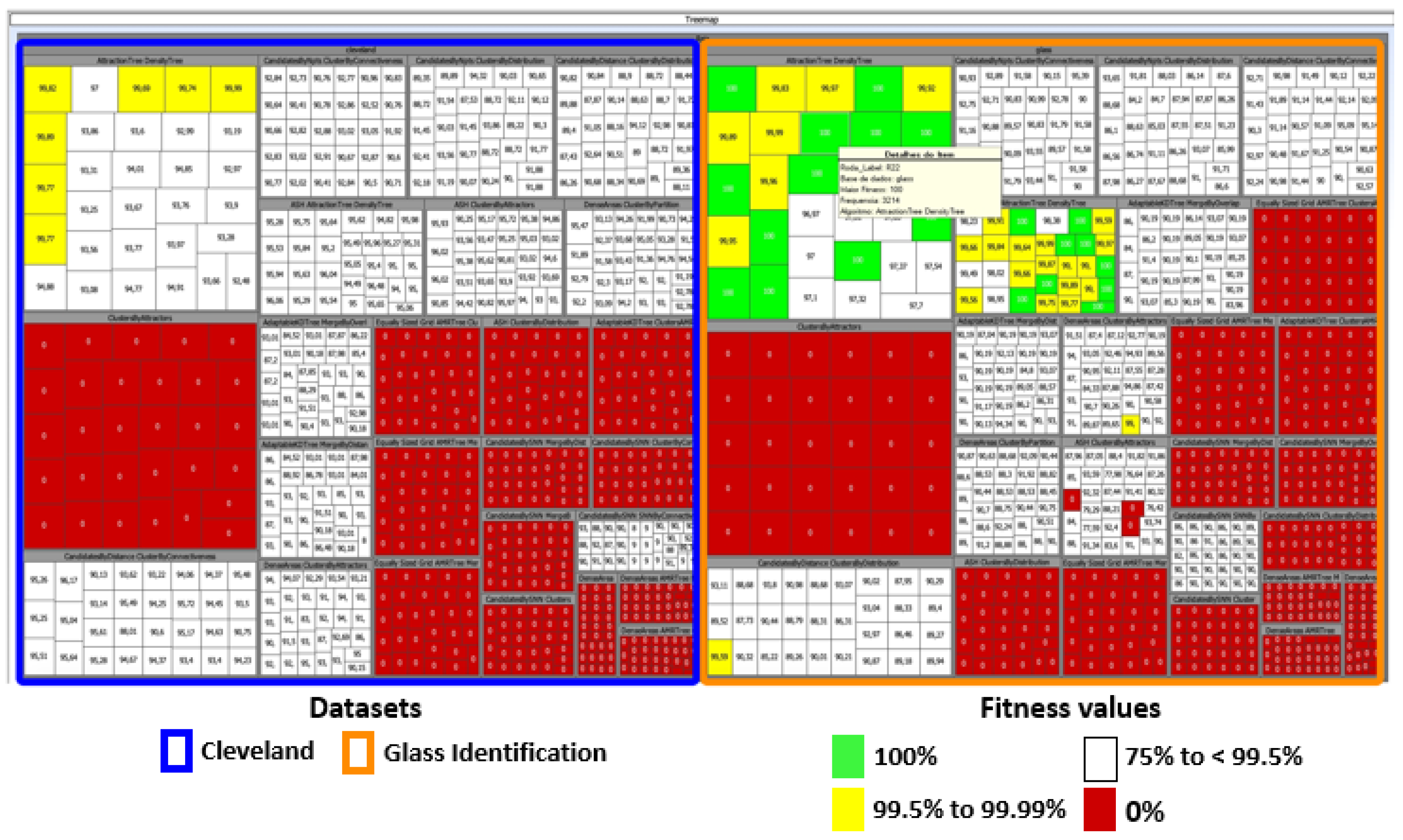

- Compare different datasets: these visualizations aim to compare the results of evolutionary techniques or tools for different datasets in order to find similarities or differences between individuals.

- -

- Comparison of individual classes in different datasets.

4.1. Test Setup and Datasets

4.2. Data Overview

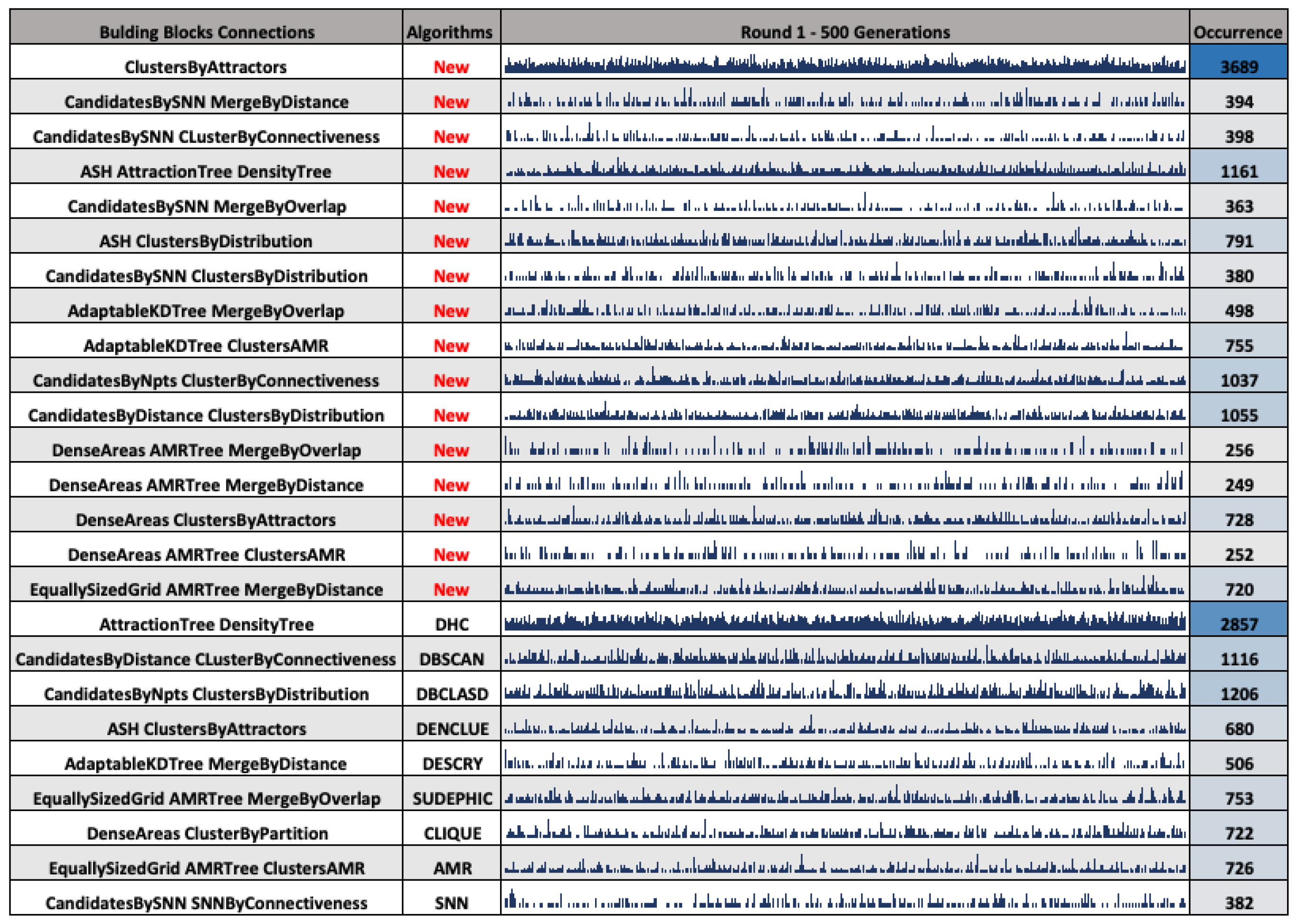

4.2.1. Type of Individuals

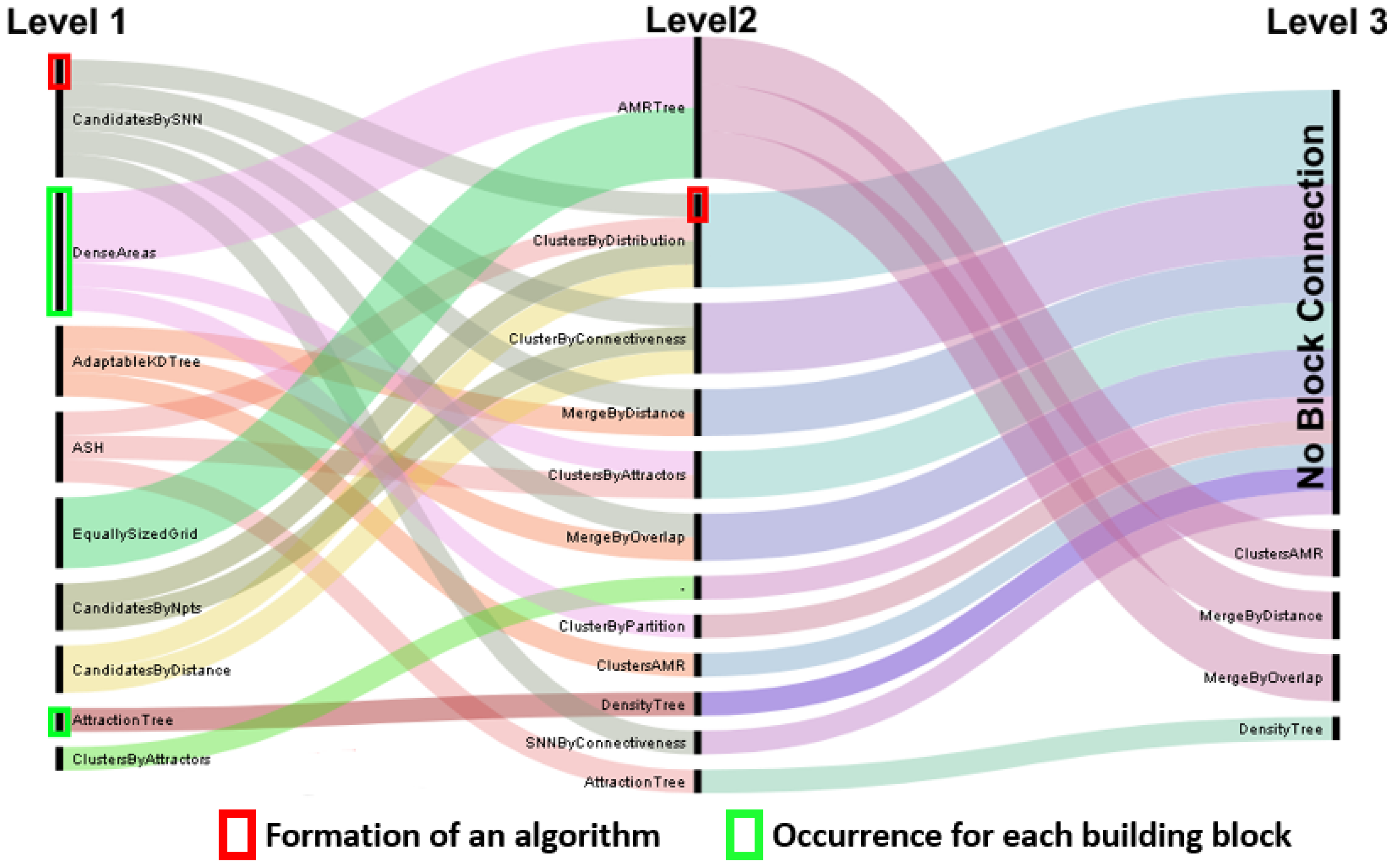

4.2.2. Occurrence of Individual Types Per Generation

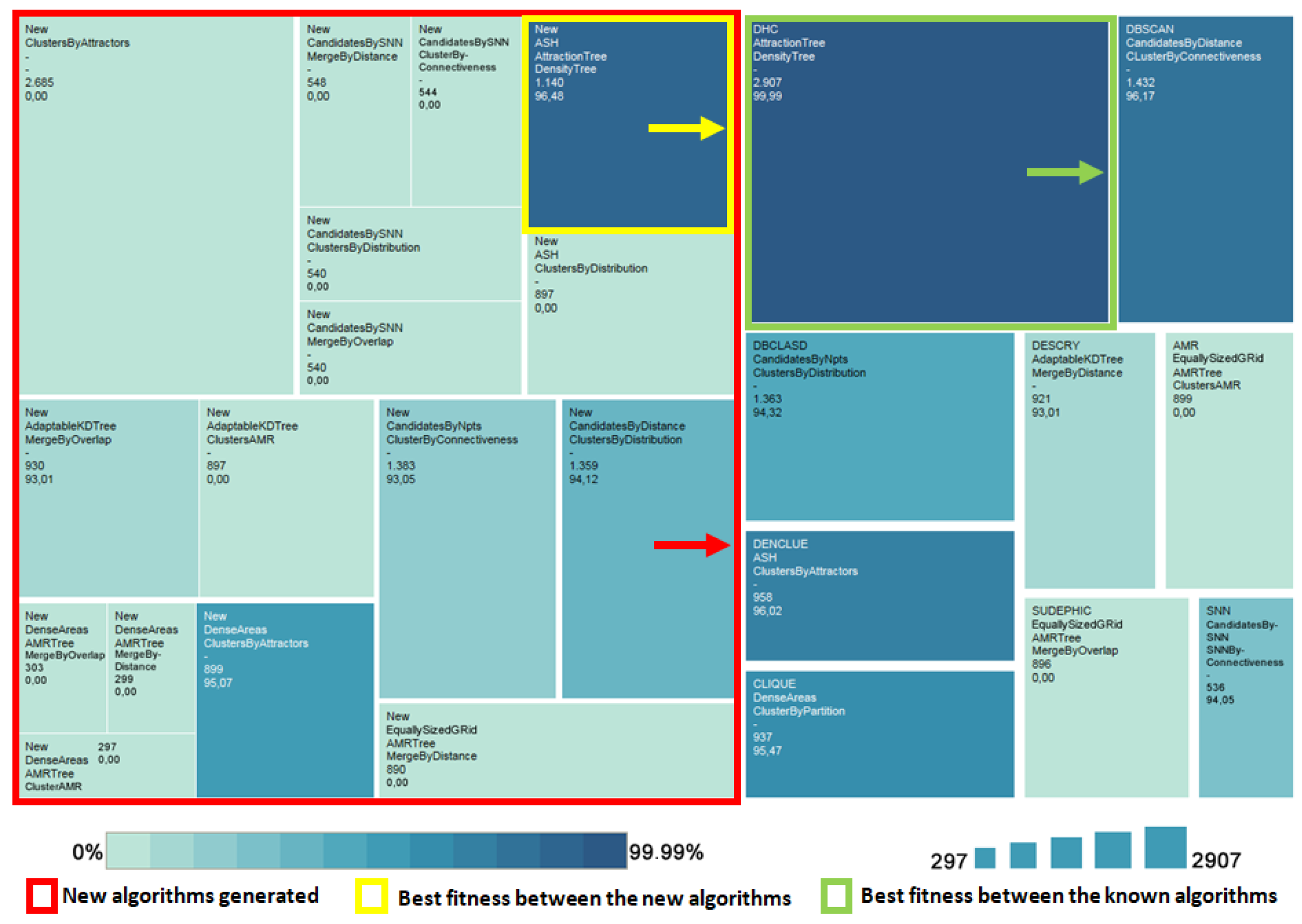

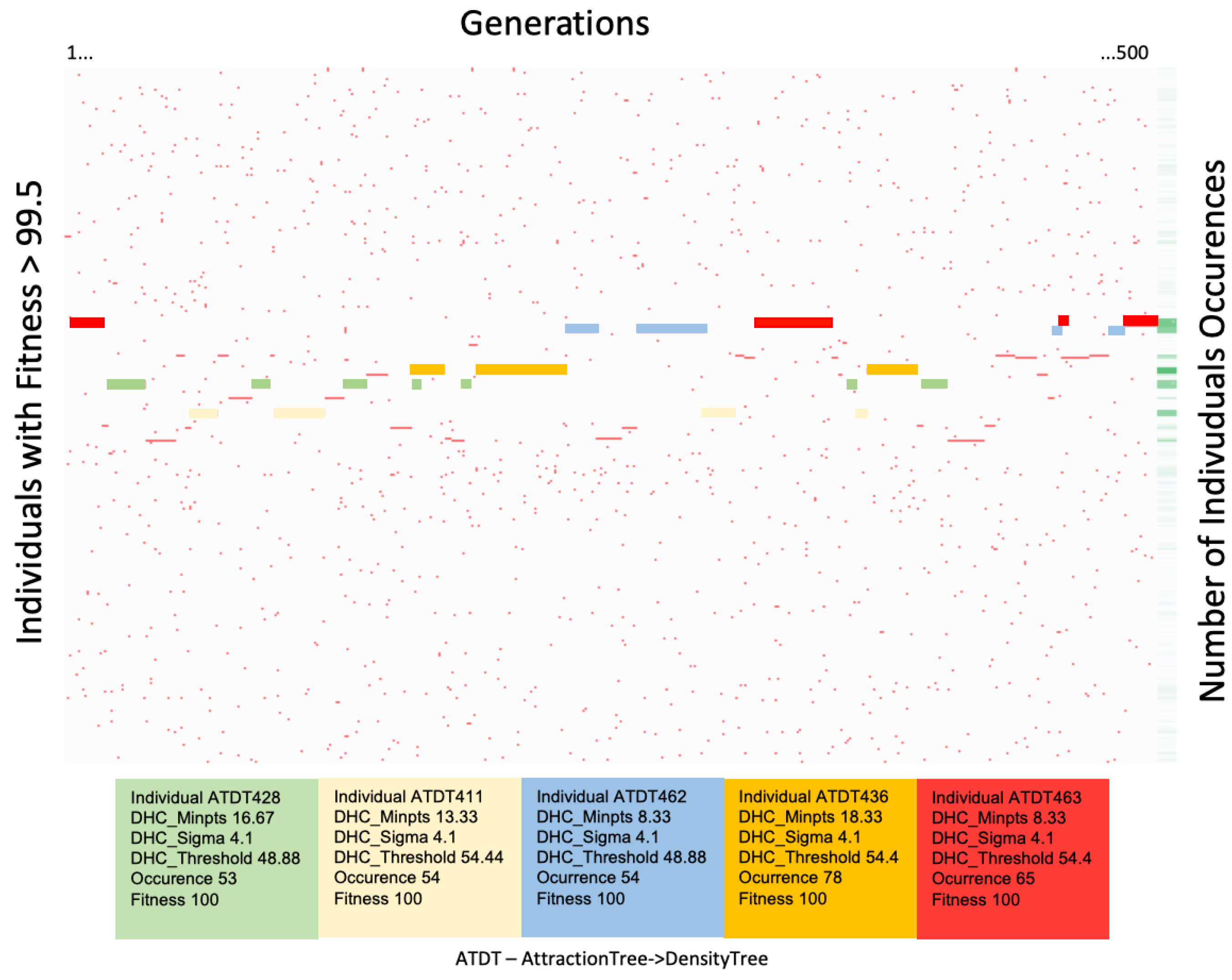

4.2.3. The Best Fitness

4.3. Tracking

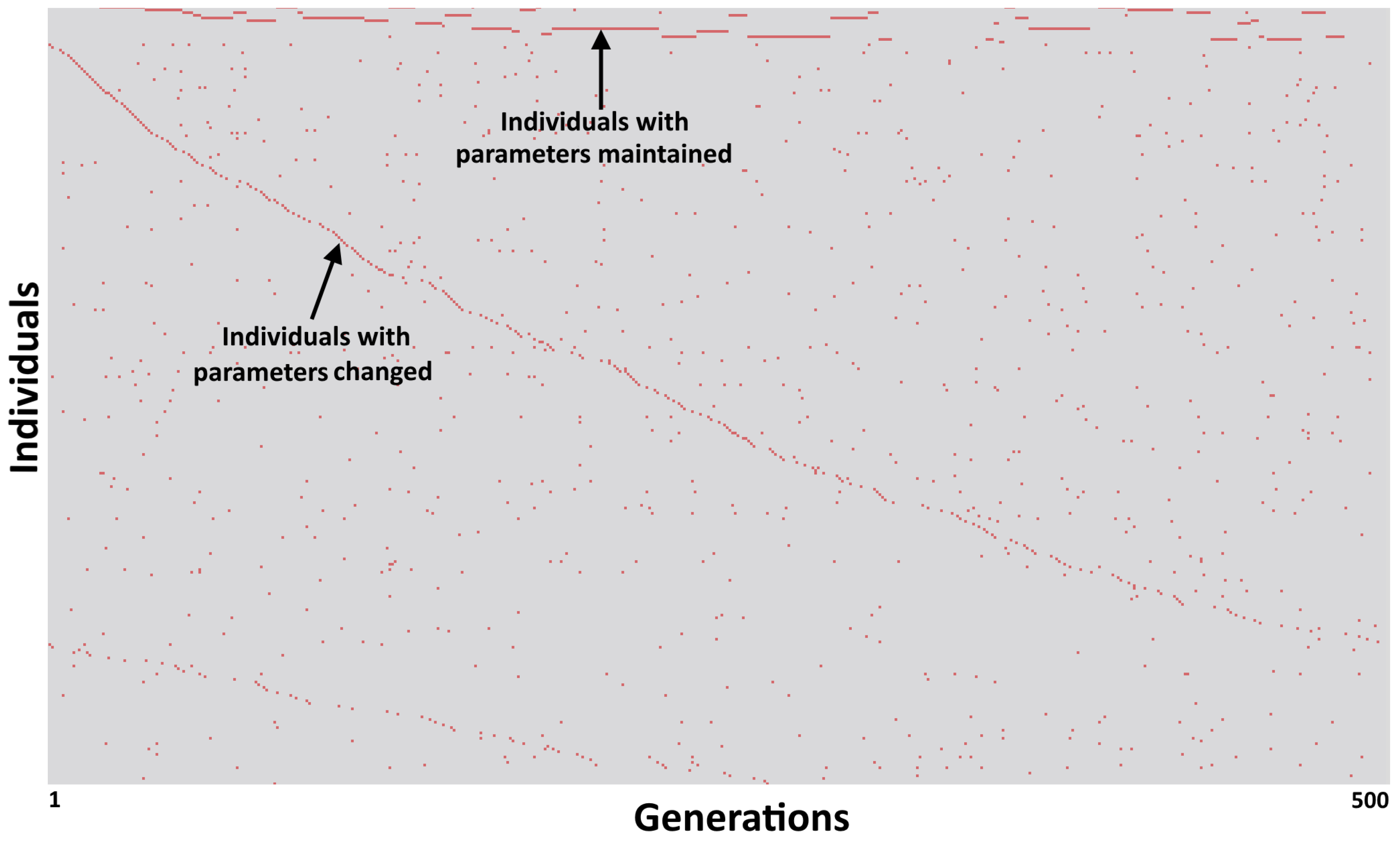

Tracking Individuals

4.4. Individuals Feature

Correlation between Fitness and Parameters

4.5. Fitness

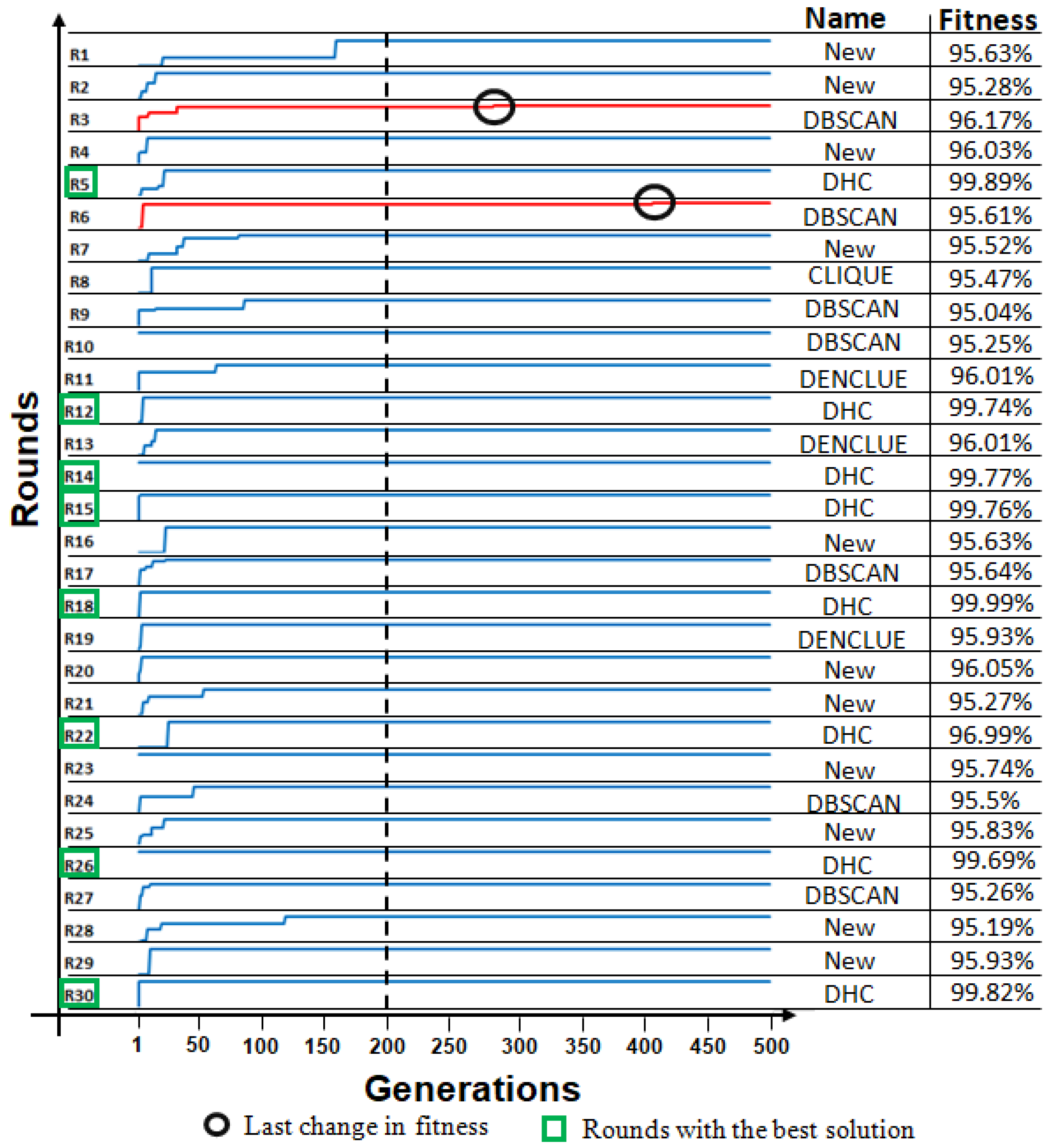

4.5.1. Fitness Evolution

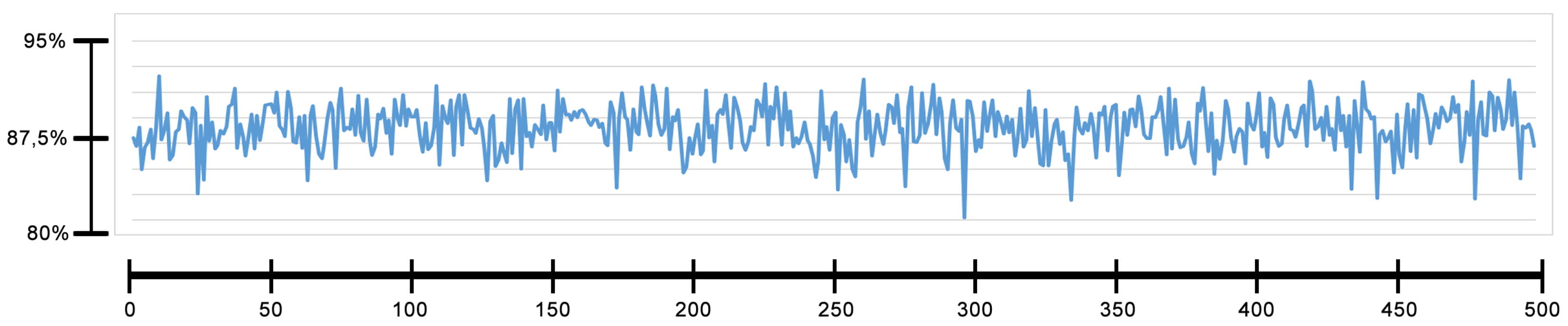

4.5.2. Average of the Fitness

4.6. Compare Different Datasets

Comparison of Algorithm Types in Different Datasets

5. Final Remarks and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinton, G.; Deng, L.; Yu, D.; Dahl, G.E.; Mohamed, A.R.; Jaitly, N.; Senior, A.; Vanhoucke, V.; Nguyen, P.; Sainath, T.N.; et al. Deep neural networks for acoustic modeling in speech recognition: The shared views of four research groups. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2012, 29, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Lai, J.; Wang, C.D. Ensemble clustering using factor graph. Pattern Recognit. 2016, 50, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attorre, B.F.M.; Silva, L.A. Open Source Tools Applied to Text Data Recovery in Big Data Environments. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Brazilian Symposium on Information Systems: Information Systems: A Computer Socio-Technical Perspective, Goiania, Brazil, 26–29 May 2015; Brazilian Computer Society: Cuiabá, Brazil, 2015; Volume 1, p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Nametala, C.A.; Pimenta, A.; Pereira, A.C.; Carrano, E.G. An Automated Investment Strategy Using Artificial Neural Networks and Econometric Predictors. In Proceedings of the XII Brazilian Symposium on Information Systems on Brazilian Symposium on Information Systems: Information Systems in the Cloud Computing Era, Santa Catarina, Brazil, 17–22 May 2016; Brazilian Computer Society: Cuiabá, Brazil, 2016; Volume 1, p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Hinneburg, A.; Keim, D.A. An efficient approach to clustering in large multimedia databases with noise. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 27–31 August 1998; Volume 98, pp. 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Do Nascimento, T.C.S.; de Miranda, L.C. Chronos Acoes: Tool to Support Decision Making for Investor of the Stock Exchange. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Brazilian Symposium on Information Systems: Information Systems: A Computer Socio-Technical Perspective, Goiania, Brazil, 26–29 May 2015; Brazilian Computer Society: Cuiabá, Brazil, 2015; Volume 1, p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Fekete, J.D. Visual analytics infrastructures: From data management to exploration. Computer 2013, 46, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Shi, J.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Zhu, J.; Liu, S. Towards better analysis of deep convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2017, 23, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mühlbacher, T.; Piringer, H.; Gratzl, S.; Sedlmair, M.; Streit, M. Opening the black box: Strategies for increased user involvement in existing algorithm implementations. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2014, 20, 1643–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portugal, I.; Alencar, P.; Cowan, D. A Preliminary Survey on Domain-Specific Languages for Machine Learning in Big Data. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Software Science, Technology and Engineering (SWSTE), Beer-Sheva, Israel, 23–24 June 2016; pp. 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Sagduyu, Y.; Grushin, A. How to steal a machine learning classifier with deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Technologies for Homeland, Waltham, MA, USA, 25–26 April 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heghedus, C.; Chakravorty, A.; Rong, C. Energy Informatics Applicability; Machine Learning and Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data, Cloud Computing, Data Science Engineering (BCD), Yonago, Japan, 12–13 July 2018; pp. 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiguins, A.S.G.; Limão, R.C.; Meiguins, B.S.; Junior, S.F.S.; Freitas, A.A. AutoClustering: An estimation of distribution algorithm for the automatic generation of clustering algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Brisbane, Australia, 10–15 June 2012; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, A.A. Data mining and Knowledge Discovery with Evolutionary Algorithms; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cagnini, H.E.L. Estimation of Distribution Algorithms for Clustering And Classification. Master’s Thesis, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Larrañaga, P.; Lozano, J.A. Estimation of Distribution Algorithms: A New Tool for Evolutionary Computation; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Norwell, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tufte, E.R.; Goeler, N.H.; Benson, R. Envisioning Information; Graphics Press: Cheshire, CT, USA, 1990; Volume 126. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, R. Information Visualization; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shneiderman, B. The eyes have it: A task by data type taxonomy for information visualizations. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Visual Languages, BouIder, CO, USA, 3–6 September 1996; pp. 336–343. [Google Scholar]

- Keim, D.; Andrienko, G.; Fekete, J.D.; Görg, C.; Kohlhammer, J.; Melançon, G. Visual analytics: Definition, process, and challenges. In Information Visualization; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 154–175. [Google Scholar]

- Keim, D.A.; Mansmann, F.; Schneidewind, J.; Ziegler, H. Challenges in visual data analysis. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Information Visualisation, London, UK, 5–7 July 2006; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Shneiderman, B. Tree visualization with tree-maps: 2-d space-filling approach. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 1992, 11, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinar, E.F. Data visualization. In Big Data at Work: The Data Science Revolution and Organizational Psychology; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2015; pp. 129–171. [Google Scholar]

- Inselberg, A.; Dimsdale, B. Parallel coordinates for visualizing multi-dimensional geometry. In Computer Graphics 1987; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1987; pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W.k.; Liu, Y.; Choudhary, A. A Grid-Based Clustering Algorithm Using Adaptive Mesh Refinement. Available online: http://users.eecs.northwestern.edu/~choudhar/Publications/LiaLiu04A.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2019).

- Agrawal, R.; Gehrke, J.; Gunopulos, D.; Raghavan, P. Automatic Subspace Clustering of High Dimensional Data for Data Mining Applications; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J. A distribution-based clustering algorithm for mining in large spatial databases. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Data Engineering, Orlando, FL, USA, 23–27 February 1998; pp. 324–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X. A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Visual Languages, BouIder, CO, USA, 3–6 September 1996; Volume 96, pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Hinneburg, A.; Keim, D.A. A general approach to clustering in large databases with noise. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2003, 5, 387–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angiulli, F.; Pizzuti, C.; Ruffolo, M. DESCRY: A density based clustering algorithm for very large data sets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Data Engineering and Automated Learning, Exeter, UK, 25–27 August 2004; pp. 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.; Pei, J.; Zhang, A. DHC: A density-based hierarchical clustering method for time series gene expression data. In Proceedings of the Third IEEE Symposium on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering, Bethesda, MD, USA, 12 March 2003; pp. 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.; Lv, H.; Sun, Q. An improved clustering algorithm based on density and shared nearest neighbor. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference, Chongqing, China, 20–22 May 2016; pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhou, H.; Wang, W.; Shi, B. SUDEPHIC: Self-tuning density-based partitioning and hierarchical clustering. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Database Systems for Advanced Applications, Bali, Indonesia, 21–24 April 2014; pp. 554–567. [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge, J.N. Replicating cluster analysis: Method, consistency, and validity. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1989, 24, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, U.; Chachoo, M. Performance evaluation of j48 and bayes algorithms for intrusion detection system. Int. J. Netw. Secur. Its Appl. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.S.; De Jong, K.A.; Burke, D.S.; Grefenstette, J.J.; Ramsey, C.L. Visual analysis of evolutionary algorithms. In Proceedings of the 1999 Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 July 1999; Volume 2, pp. 1419–1425. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Zhu, J. Towards better analysis of machine learning models: A visual analytics perspective. Vis. Inform. 2017, 1, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.; Machado, P.; Assunção, F.; Leitão, A. Elicit: Evolutionary computation visualization. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 2015 Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation, Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2015; pp. 949–956. [Google Scholar]

- McPhee, N.F.; Casale, M.M.; Finzel, M.; Helmuth, T.; Spector, L. Visualizing Genetic Programming Ancestries. In Proceedings of the 2016 on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion, Denver, CO, USA, 20–24 July 2016; pp. 1419–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Daneshpajouh, H.; Zakaria, N. A Clustering-based Visual Analysis Tool for Genetic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications, Porto, Portugal, 27 February–1 March 2017; pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Munzner, T. Visualization Analysis and Design; AK Peters/CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, R.; Bielza, C.; Larranaga, P.; Lozano, J.A.; Echegoyen, C.; Mendiburu, A.; Armananzas, R.; Shakya, S. Mateda-2.0: Estimation of distribution algorithms in MATLAB. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 35, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichman, M. UCI Machine Learning Repository; University of California: Oakland, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brito, Y.; Santos, C.; Mendonca, S.; Arújo, T.D.; Freitas, A.; Meiguins, B. A Prototype Application to Generate Synthetic Datasets for Information Visualization Evaluations. In Proceedings of the 2018 22nd International Conference Information Visualisation (IV), Fisciano, Italy, 10–13 July 2018; pp. 153–158. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meiguins, A.; Santos, Y.; Santos, D.; Meiguins, B.; Morais, J. Visual Analysis Scenarios for Understanding Evolutionary Computational Techniques’ Behavior. Information 2019, 10, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/info10030088

Meiguins A, Santos Y, Santos D, Meiguins B, Morais J. Visual Analysis Scenarios for Understanding Evolutionary Computational Techniques’ Behavior. Information. 2019; 10(3):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/info10030088

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeiguins, Aruanda, Yuri Santos, Diego Santos, Bianchi Meiguins, and Jefferson Morais. 2019. "Visual Analysis Scenarios for Understanding Evolutionary Computational Techniques’ Behavior" Information 10, no. 3: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/info10030088

APA StyleMeiguins, A., Santos, Y., Santos, D., Meiguins, B., & Morais, J. (2019). Visual Analysis Scenarios for Understanding Evolutionary Computational Techniques’ Behavior. Information, 10(3), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/info10030088