Information: A Conceptual Investigation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. What Information Is Not

2.1. Uncertainty

Thus, the specific focus of these approaches is explicitly not meant to contribute to a general clarification of the concept of information. In particular, it is not the intention of this approach to explain what information (in a general sense) might be. Shannon’s theory defines a way to measure information, it does not explain what it is. But the latter point is exactly addressed when seeking for a characterization of the concept of information. As concepts must inherently be associated with meaning, no conceptual characterization can circumvent meaning. So if we don’t have meaning at hand, it is not to be seen how a conceptual clarification may evolve. This excludes any approaches from our investigation that do not involve meaning.Frequently the messages have meaning; that is, they refer to or are correlated according to some system with certain physical or conceptual entities. These semantic aspects of communication are irrelevant to the engineering problem.

2.2. Semantic Information and Information Flow

In the sequel, we adopt Dretske’s notion of a ‘cognitive system’, which, however, will be subject to further specifications.Once this distinction [of information and meaning] is clearly understood, one is free to think about information (though not meaning) as an objective commodity, something whose generation, transmission, and reception do not require or in any way presuppose interpretive processes. One is therefore given a framework for understanding how meaning can evolve, how genuine cognitive systems […] can develop out of lower-order, purely physical, information-processing mechanisms. […] The raw material is information.(cf. [12]; p. vii)

2.3. Perception and Epistemology

2.4. Information Reviewed

3. Information and Knowledge

[…] to describe the active and a posteriori action of the mind depicting something unknown or helping memory, as part of the ars memoriae, to better remember a past situation through the pictorial representation of a sentence (sententiae informatio).(cf. [30]; p. 352)

4. Conceptualizations of Information

4.1. Concepts Associated with Information

In this definition, information is understood to be the result of a transformative process that relies on a general understanding of terms like useful, purpose, and understanding. Interestingly, information is then further described as the result of a process that “reduces uncertainty” (cf. [36]; p. 6). This additional remark hints at understandings of ‘information’ that have been suggested by Shannon and others; as discussed above, these understandings attempt to turn the definition into a formally treatable form but result in a neglected conceptual reduction.Information is generally considered to designate data arranged in ordered and useful form. Thus, information will usually be thought of as relevant knowledge, produced as output of processing operations, and acquired to provide insight in order to (1) achieve specific purposes or (2) enhance understanding.

4.1.1. Practice

“Information” is the judgment […] that given data resolve questions. In other words, information is the meaning someone assigns to data. Information thus exists in the eyes of the beholder.(cf. [39]; p. 20)

4.1.2. Wisdom

4.2. Conceptualizations of Information in Organizational Units

…knowledge as a dynamic human process of justifying personal belief toward the ‘truth’.(cf. [42]; p. 58)

Not only are the definitions of the three entities vague and imprecise; the relationships between them are not sufficiently covered.

This image holds two tacit assumptions; firstly, it implies that the relationship is asymmetrical, suggesting that data may be transformed into information, which, in turn, may be transformed into knowledge. However, it does not seem to be possible to go the other way.

One of the most important characteristics of knowledge is abstraction, the suppression of detail until it is needed […]. Knowledge is minimization of information gathering and reading – not increased access to information. Effective knowledge helps you eliminate or avoid what you don’t want. Such abstraction also enables you to make judgments in a variety of situations, to generalize.

- to access individual experience (“tacit knowledge”)

- to collect it in a form available for the unit (“knowledge management”)

- to extract the valuable core of this knowledge (“abstraction”)

- to verify its contents (“true facts”)

- to represent these in a form that can be utilized (“explicit Knowledge”).

4.3. Conceptualizations of Information in Information Science

4.3.1. Information as Difference

4.3.2. Information as a Process

4.3.3. Information as Transformation

4.3.4. Modification of Knowledge Structures

- The internal constitution of the structure.

- The nature or ‘carriers’ of the external influences that “make a difference.”

- The alteration of the structure after an effect by external influences.

4.3.5. Information and Knowledge

4.3.6. Information and Data

4.3.7. Information and Meaning

Something only becomes information when it is assigned a significance, interpreted as a sign, by some cognitive agent.(cf. [12]; p. vii)

4.3.8. Formalization of Information

…states in its very general way that the knowledge structure is changed to the new modified structure by the information , the indication the effect of the modification.(cf. [61]; p. 131)

5. The Philosophical Background

5.1. Pragmatism

Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object.(cf. [59]; paragraph 5.402)

- Firstness is the mode of being of that which is such as it is, positively and without reference to anything else.

- Secondness is the mode of being of that which is such as it is, with respect to a second but regardless of any third.

- Thirdness is the mode of being of that which is such as it is, in bringing a second and third into relation to each other.

[Semiosis is] an action, or influence, which is, or which involves, a cooperation of three subjects, such as a sign, its object, and its interpretant, this tri-relative influence not being in any way resolvable into actions between pairs.(cf. [59]; paragraph 5.484)

A sign, or Representamen, is a First which stands in such a genuine triadic relation to a Second, called its Object, as to be capable of determining a Third, called its Interpretant, to assume the same triadic relation to its Object in which it stands itself to the same object. The triadic relation is genuine, that is its three members are bound together by it in a way that does not consist in any complexus of dyadic relations.

A sign, or representamen, is something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity. It addresses somebody, that is, creates in the mind of that person an equivalent sign, or perhaps a more developed sign. That sign which it creates I call the interpretant of the first sign. The sign stands for something, its object. It stands for that object, not in all respects, but in reference to a sort of idea, which I have sometimes called the ground of the representamen.

5.2. Morris’ Analytical Reductions

- (1)

- syntactics, the study of “the formal relations of signs to one another”;

- (2)

- semantics, the study of “the relations of signs to the objects to which the signs are applicable”;

- (3)

- pragmatics, the study of “the relation of signs to interpreters”.

6. A Semiotic View of Information

6.1. Data Denotes the Syntactical Dimension of a Sign

6.2. Knowledge Denotes the Semantical Dimension of a Sign.

- (1)

- It is abstracted from the process of the semiosis as a whole and only its result is under consideration.

- (2)

- The reduction of the dimensions reflects intersubjectivity and, as such, must not depend on a concrete interpreter.

- universally valid;This would be ideal for a pure semantic characterization—a characterization that does not take into account who produced it and is, in general, the pretension of truth. However, even Tarski’s semantic theory of truth [19] in mathematics has not experienced general acceptance as a universal methodology and remains bound to the Hilbert-Tarski-style of mathematics. See, for example, constructive mathematics in the sense of Brouwer [82] for an alternative approach.There are no other apparent grounds for a universally accepted methodology; thus, this claim must be considered a “regulative idea” (in the sense of Kant) and may only be approximated in reality.

- dependent on presuppositions;If we give up a unifying, universal view on truth (as the different conceptions of truth indicate) we end up with a diversity of conflicting understandings. Accordingly, the unifying pretension of validity vanishes as well. This implies a community that shares presuppositions. Hence, the abstraction determining the semantic nature of the knowledge is only acknowledged by and accepted in this community. As a result, we find a diversity of competing understandings. Thus, knowledge represents a system’s view only; it is bound to a shared understanding within a community.

- only subjective;In general, this does not count for knowledge, but may qualify as the starting point for knowledge. In this sense, it is the basis for any process resulting in knowledge (cf. the abstract characterization of knowledge described later).

6.3. Information Denotes the Pragmatic Dimension of a Sign.

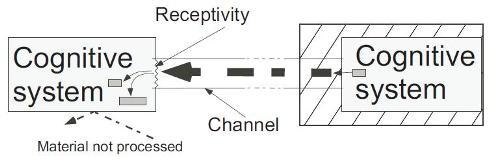

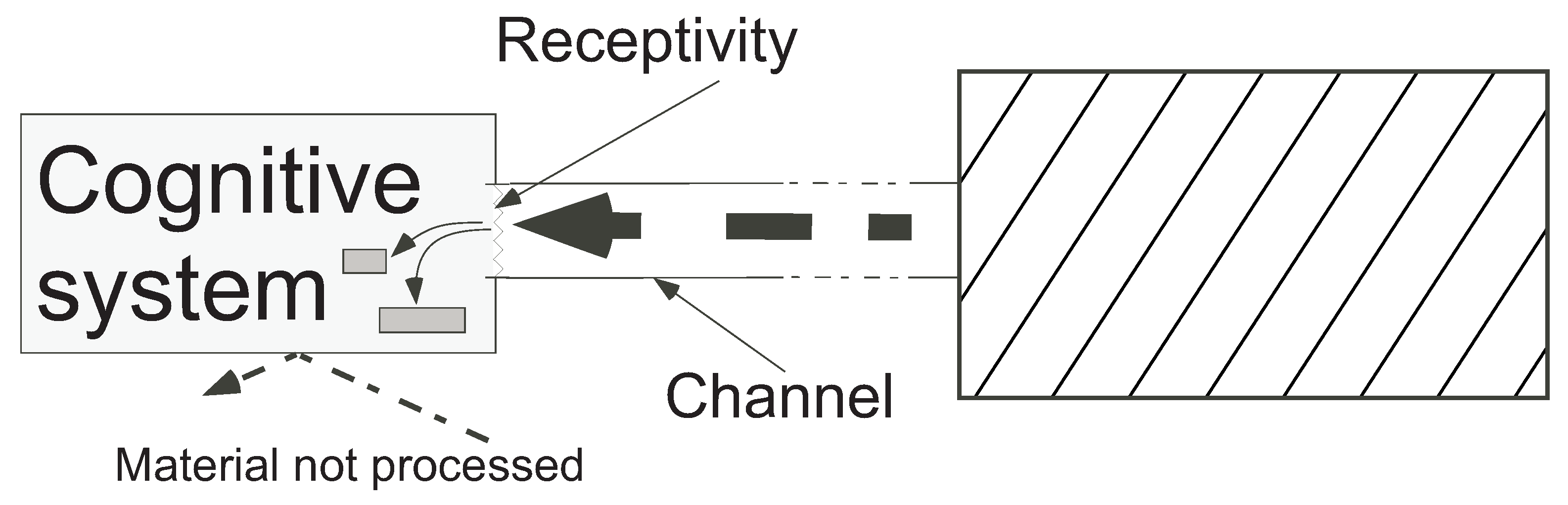

Moreover, this appropriation necessarily involves a communication act as described in Figure 2. To speak of ‘information’ therefore requires two different cognitive systems: the one that produces the knowledge item and the one that tries to appropriate it. But what actually goes through the ‘channel’ in Figure 2 (or, in other words, what is communicated between the two cognitive systems) is only data, the syntactical dimension of the sign. The other dimensions are determined by the system’s property and thus are not attached to or otherwise connected with the sign. Information as external knowledge is presented to the communication system simply as data, without this justification. The associated interpretation and justification are the system’s properties and, as such, are not present in what is communicated[84]. The mere exchange of data—the pure communication act—must be complemented by an attempt to re-create the other semiotic dimensions that had been associated with that data in the external system. This is what is meant by appropriation. Because it is indeed a re-interpretation, this process has the potential to either succeed or fail. The result of the process may either fit into the knowledge system or generate inconsistencies.It is common among cognitive scientists to regard information as a creation of the mind, as something we conscious agents assign to, or impose on, otherwise meaningless events. Information, like beauty, is in the mind of the beholder.

7. Knowledge as a Conceptual Basis for Information

7.1. The Concept of Knowledge

7.2. Truth as a Criterion

7.3. Mathematics as the Ideal Scientific Discipline?

7.4. Knowledge in Mathematics

- a constitution of objects in a formal language (Frege’s Begriffssprache) as data

- a concept of meaning specifically tailored for mathematics along with

- a conception of validity, i.e., truth (see [19])

- a constitution of validity that excludes self-referential constructions

- logical inference rules preserving truth

- a dependency structure provided by a concept of justification (‘proof’)

8. Information

8.1. Information and Uncertainty

8.2. Information and Knowledge

- Information as the basis for knowledge.This kind of dependence seems trivial at first: simply neglect or ignore the impact of the pragmatic dimension of information. But information is also knowledge. So this pragmatic dimension is reflected in the system’s constitution from which the information stems. Just putting this dimension aside would affect the whole system’s internal constitution and, consequently, the basis for the constitution of this item as knowledge as well. Thus, we either must have some legitimate reason to do so, or we turn knowledge into pure belief, which is not as reliable as knowledge (cf. the characterization of knowledge presented above). Hence, this cannot be done without disqualifying it as knowledge at all. So the conditions and specific commitment to which the process of knowledge generation is bound may not simply be ignored. Instead, it must be expected that information is taken out of something that may rightly claim to be knowledge.Remember, however, that information essentially includes an aspect of externality. Hence, it necessarily remains external and thus potentially beyond our control. In other words, we are not necessarily able to understand why some given conviction bears some degree of validity or why it can be legitimately considered knowledge in the external knowledge system. Instead, we may simply trust in and try to appropriate it. Thus, in principle there is no safe basis to turn information into knowledge. This is the reason for the aspect of uncertainty necessarily associated with information.Moreover, for knowledge based on information, there is necessarily an interpretation process associated (remember that only data is exchanged). Such an interpretation process has to address the problem of coherence or consistency of the possibly different justification processes associated with the information item (the data) and the knowledge system under consideration, respectively. In any case, it must be observed that no incompatible views are merged. This is exactly the task of the appropriation process.

- Knowledge as a basis for information.Knowledge—which must be knowledge inside a knowledge (or cognitive) system—may only be turned into information in view of another knowledge (or cognitive) system. However, an internal constitution—its internal commitments—predetermines what could be considered knowledge within the system and is thus involved in the constitution of knowledge. One might think of attempts to communicate these commitments in (meta-)communication. This may indeed be successful, to a certain extent. But an appropriation process is needed to accommodate it anyway, which may be supported—but certainly not substituted—by this additional communication level.

8.3. Re-Interpretation of Conceptualizations of Information

- (1)

- Information is […] a difference that makes a difference.This characterization suggests that we need a “doubtful situation”, one that is not already covered by the contents of our knowledge system. In such a situation we need “a difference”, some additional external knowledge item (information) that is not contained in the knowledge system. The intention is to gain hints to overcome the crucial situation that triggered the need for information. This means that it should indeed “make a difference”, or properly extend our knowledge base.

- (2)

- Information is […] the values of characteristics in the processes’ output.The “process” mentioned in this statement may be understood as referring to the process of information seeking and subsequent appropriation of external knowledge. Both kinds of processes are involved in the steps to dissolve the “doubtful situation” that is the starting point for the request for information. Of interest, however, is the result of these processes, the “output”. As a result of the information-seeking process, we are confronted with mere data. The “characteristics” of data must be exhibited and (hopefully) evaluated in a positive way, such that the data may contribute to a solution. In other words, its “value” has to be established. This is what appropriation must perform, such that the “doubtful situation” vanishes.

- (3)

- Information is that which is capable of transforming structure.This item emphasizes the expectation of information. As stated in point (1), information must at least have the potential (being “capable”) to dissolve the “doubtful situation” by extending the knowledge system appropriately (“transforming structure”). If this does not happen, we cannot speak of information.

- (4)

- Information is that which modifies […] a knowledge structure.This statement is similar to statement (3), but concentrates on the effect of information on knowledge systems (“structures”). “Capabilities” are not the focus but the result, the actual extension of the knowledge system (“modifies”) after the appropriation of information from some other source.

- (5)

- Knowledge is a linked structure of concepts.In this paper, we have shown that the semantic dimension of knowledge does not mean that a dimension is totally missing (see the discussion at the beginning of this section). Instead, it must be subject to a legitimate abstraction, which is only possible if it is able to rely on the respective grounds of a system’s constitution.Point (5) suggests that the necessary systemic character of knowledge is a consequence of its semantic nature. It argues that the system must not merely be some amorphous compilation of knowledge items without internal structure but must provide the basis on which the abstraction can be performed, which is not possible without this internal constitution of the knowledge system.

- (6)

- Information is a small part of such a structure.This item supports the view that information must be knowledge—external knowledge, to be precise, but knowledge nonetheless. It cannot be less; information cannot be pure belief or even mere data. On the contrary: it must have a background in some (external) knowledge system. Subjective belief with no indication of justification remains arbitrary and certainly does not count as information. Information must be more; it must at least indicate its origin, including some kind of justification (which, however, has still to be appropriated).

- (7)

- Information can be viewed as a collection of symbols.Statement (7) hints at what can only be communicated or transferred between cognitive systems: it is data, or the syntactical dimension of a sign. It concentrates on the carriers of information and emphasizes that we do not have more at first hand. However, we do know with whom or what the communication process has been performed. By exploiting the necessary setting of this basic situation as given in Figure 2, we may infer more, such as whether the data indeed stem from an external knowledge structure or from some other source.

- (8)

- This is again the famous “fundamental equation” that illustrates the basic situation in which we may speak of information. Aspects of this equation can be found in the discussion of statements (1) through (7). “” may be interpreted as the “small piece of such a structure” in (6), “” is the knowledge system and “” is the effect of “” on the the knowledge system “” (namely that information causes an extension of the knowledge system and would not otherwise qualify as information). Moreover, the “” must be subject to an appropriation process, which turns it into something different: “”.We have shown that this equation incorporates—in coded, symbolic form—fundamental determinants of the concept of ‘information’ along with its relationship to the concepts necessarily connected with it, as described in the previous sections of this paper. In this sense, this paper contributes to the general research program formulated by Brookes (cf. [61]; p. 117), who stated:The interpretation of the fundamental equation is the basic research task of information science.This is exactly what we have done in this paper.

- (9)

- tacit knowledgeIn this additional item, we again refer to the discussion of “tacit knowledge” and comment on it based on our discussion so far. As mentioned above, external knowledge (“information”) is potentially beyond our control and solely bound to the external system’s constitution. As this may lead to inconsistencies, special attention must be paid to the conditions under which a comprehension of information into a knowledge system is possible at all.This problem applies to any compilation of what is called “tacit knowledge” into an integrated whole. Because the different information items may be based on incompatible processes of their respective genesis, the integrated system may easily show incoherence, inconsistency or contradiction such that, in effect, no knowledge system can be established on the basis of the integrated compilation. Instead, “anything goes” (or, in logical terms, “ex falso quodlibet”).It is important to ensure that no incompatible views are merged. This means that all items of such a collection have to undergo an appropriation process. As there may be inconsistencies between those information items, decisions have to be made about how to handle such inconsistencies in case they arise during such an appropriation process [109].

9. Conclusions

References and Notes

- Floridi, L. Open problems in the Philosophy of Information. Metaphilosophy 2004, 35, 554–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell. Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423, 623–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- We are well aware that, as in many fields of inquiry, this important work built on that of predecessors. Nyquist [110] studied the limits of a telephone cable for the transmission of ‘information’, and Hartley [111] developed a conceptualization of information based on “physical as contrasted with psychological considerations” for studying electronic communication. See also [58] for a short survey of the development of ‘information theory’. The break-through, however, may certainly be associated with the papers mentioned above.

- Hintikka, K.J.J. On semantic information. In Information and Inference; Hintikka, K.J.J., Suppes, P., Eds.; Reidel: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1970; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- In [59] (paragraph 5.404) Peirce provides an example by considering the idea of a force. He discusses the claim of the German Physicist Kirchhoff stating that although we understand precisely the effect of force, we do not understand at all what force itself is.

- Bar-Hillel, Y.; Carnap, R. An Outline of a Theory of Semantic Information; Technical report no. 247; Research Laboratory for Electronics, MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K.R. Logik der Forschung; Springer: Wien, Austria, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K.R. Degree of Confirmation. Brit. J. Phil. Sci. 1954, 5, 143–149, Correction ibid. 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Hillel, Y.; Carnap, R. Semantic Information. Brit. J. Phil. Sci. 1953, 4, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemeny, J.G. A Logical Measure Function. J. Symb. Logic. 1953, 18, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dretske, F. Knowledge and the Flow of Information; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Barwise, K.J.; Perry, J. Situations and Attitudes; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, K. Logic and information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barwise, J.; Seligman, J. Information Flow: The Logic of Distributed Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Floridi, L. Outline of a Theory of Strongly Semantic Information. Available online: http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/2537/1/otssi.pdf (last accessed on 15 October 2010).

- Floridi, L. Is Information Meaningful Data? Available online: http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/2536/1/iimd.pdf (last accessed on 15 October 2010).

- Israel, D.; Perry, J. What is Information? In Information, Language, and Cognition; Hanson, Ph., Ed.; University of British Columbia Press: Vancouver, Canada, 1990; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tarski, A. Der Wahrheitsbegriff in den Sprachen der deduktiven Disziplinen. Anz. Österr. Akad. Wiss. Math.-Nat. Klasse. 1932, 69, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Natterer, P. Systematischer Kommentar zur Kritik der reinen Vernunft; de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, I. Gesammelte Schriften; Akademie-Ausgabe: Berlin, Germany, 1900ff; Volumes. I–XXIII. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig, M.R.; Breedlove, S.M.; Watson, N.V. Biological Psychology: An Introduction to Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience, 4th ed.; Sinauer: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dretske, F. Seeing and Knowing; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Dretske, F. Knowledge and the Flow of Information; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, I. Kritik der reinen Vernunft; Riga, Latvia, 1789. [Google Scholar]

- We do not want to commit ourselves to any philosophical position at this point in this paper. In fact, we think that virtually any philosophical position, from naive realism to idealism, will comply with the arguments presented in this paper.

- Schnelle, H. Information. In Historisches Wörterbuch der Philosophie; Ritter, J., Gründer, K., Eds.; Schwabe & Co. Verlag: Basel, Stuttgart, Germany, 1976; Volume 4, pp. 156–357. [Google Scholar]

- Thesaurus linguae latinae [Thesaurus of the Latin language]; Teubner: Leipzig, Germany, 1900ff; (See also the revised edition published by de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1992ff.).

- Capurro, R. Information. Ein Beitrag zur Etymologischen und Ideengeschichtlichen Begründung des Informationsbegriffs; Saur: München, Germany, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Capurro, R.; Hjørland, B. The Concept of Information. Annu. Rev. Inform. Sci. Tech. 2003, 37, 343–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.; Weiner, E. (Eds.) Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1989.

- Peters, J.D. Information: Notes toward a critical history. J. Commun. Inq. 1988, 12, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- For a discussion of related positions see also Brian Cantwell Smith’s forthcoming book [112] whose aim is to provide a comprehensive, systematic, philosophically rigorous analysis of the foundations of computing. See especially volume I, chapters 3 and 5 on meaning.

- Brookes, B.C. The Developing cognitive viewpoint in information science. In International Workshop on the Cognitive Viewpoint; de Mey, M., Ed.; University of Ghent: Ghent, Belgium, 1977; pp. 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ingwersen, P. Information Retrieval Interaction; Taylor Graham: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, D.H. Computers in Society; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Task Force on Computing Curricula IEEE Computer Society Association for Computing Machinery. Computing Curricula 2001 Computer Science. Final Report. Available online: www.acm.org/education/curric_vols/cc2001.pdf (last accessed on 15 October 2010).

- Shackelford, R.; McGettrick, A.; Sloan, R.; Topi, H.; Davies, G.; Kamali, R.; Cross, J.; Impagliazzo, J.; LeBlanc, R.; Lunt, B. Computing Curricula 2005: The Overview Report. In Proceedings of the 37th SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education; ACM: Houston, TX, USA, 2006; pp. 456–457. [Google Scholar]

- Denning, P.J. The IT Scholl Movement. Commun. ACM 2001, 44, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehlen, A. Der Mensch: Seine Natur und seine Stellung in der Welt. In Gehlen, Arnold Gesamtausgabe; Rehberg, K.-S., Ed.; Vittorio Klostermann: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ackoff, R.L. Transformational consulting. Manage. Consult. Times 1997, 28, No. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dunham, R. Knowledge in action: the new business battleground. KM Metazine 1996, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, M. Tacit Dimension; Doubleday: Garden City, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. The Tree of Knowledge; Shambala: Boston, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- van der Spek, R.; Spijkervet, A. Knowledge Management: Dealing Intelligently with Knowledge; CIBIT: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, C.W.; Detlor, D.; Turnbull, D. Web Work: Information Seeking and Knowledge Work on the World Wide Web; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark, D. The Relationship between Information and Knowledge. In Proceedings of the 24th Information Systems Research Seminar in Scandinavia (IRIS 24), Ulvik, Hardanger, Norway, August 2001.

- Murray, Ph.C. Information, knowledge, and document management technology. KM Metazine 1996, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mattessich, R. On the nature of information and knowledge and the interpretation in the economic sciences. Libr. Trends 1993, 41, 567–593. [Google Scholar]

- Wiig, K.M. Knowledge Management Foundations: Thinking About Thinking—How People and Organizations Represent, Create, and Use Knowledge; Schema Press: Arlington, TX, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi, M. Personal Knowledge, corrected ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, C.W. The Knowing Organization; Oxforf University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomi, I. Data is more than Knowledge: Implications of the Reversed Knowledge Hierarchy for Knowledge Management and Organizational Memory. J. Manage. Inform. Syst. 1999, 16, 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomi, I. Corporate Knowledge: Theory and Practice of Intelligent Organizations; Metaxis: Helsinki, Finland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unit; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind; Paladin: St. Albans, Australia, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Losee, R.M. A Discipline Independent Definition of Information. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1997, 48, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, C.S. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce; Hartshorne, Ch., Weiss, P., Burks, A.W., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1931–1958; Volumes 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Belkin, N.J.; Robertson, S.E. Information Science and the Phenomenon of Information. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 1976, 4, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, B.C. The Foundations of Information Science. Part I. Philosophical Aspects. J. Inform. Sci. 1980, 2, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R. Measuring Information Output: A communication Systems Approach. Inform. Manage. 1978, 1, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizzaro, S. On the Foundations of Information Retrieval. In Proceedings of the annual Conference AICA’96; Rome, Italy, 1996; pp. 363–386.

- Mizzaro, S. Towards a Theory of Epistemic Information. In Information Modelling and Knowledge Bases XII; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brookes, B.C. The fundamental equation in information science. In Problems of Information Science, FID 530; VINITI: Moscow, Russia, 1975; pp. 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hookway, Ch. Peirce; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, K.A. The Continuity of Peirce’s Thought; Vanderbilt University Press: Nashville, TN, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fisch, M.H. Introduction to Writings of Charles S. Peirce; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Deledalle, G. Charles S. Peirce: An Intellectual Biography; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Murphey, M.G. The Development of Peirce’s Philosophy; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Gallie, W.B. Peirce and Pragmatism; Penguin: Harmondsworth, UK, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Buckler, J. (Ed.) Philosophical writings of Peirce; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1955.

- Morris, Ch.W. Signs, Language, and Behaviour; Prentice-Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Ch.W. Foundation of the theory of signs. In International Encyclopedia of Unified Science; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1938; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Carnap, R. Foundations of Logic and Mathematics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport, W.J. How to Pass a Turing Test: Syntactic Semantics, Natural-Language Understanding, and First-Person Cognition. J. Logic. Lang. Inf. 2000, 9, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathematical practice, however, is sometimes different. As mathematics has a semantical foundation (cf. Tarski’s conception of truth [19]), it claims intersubjective validity; see also the next section for this point. But in practice this validity is not necessarily guaranteed. There are known examples in the history of mathematics where this is not the case. See, e.g., the proof of the 0”’-priority method in logic [113], which initially was not really understood in the community by only studying the paper.

- Cf. logic as a basis for knowledge: there must be an underlying formal language—the/a language of logic—on which logic is able to operate. Furthermore, a form capable of representing elementary knowledge has to be established on which logic can operate. See Aristotle, who began the analysis of the elementary structure of something that is capable of logical deductions: it is the “ti kata tinos”, the something about something. In Frege’s conception of modern logic, concepts are considered as truth-functions themselves and thus, in a direct and immediate way, associate concepts (as 1-place relations) with knowledge.

- ‘Private conviction’ will stand for the Greek doxa as used by Plato in the context of knowledge (see [90]). For reasons that cannot be fully explained in this paper (see [107] for more details), we have chosen to use this notion instead of ‘belief’, which is more common in the tradition of the discussion of knowledge.

- To relate this epistemological view to certainty goes (at least) back to Descartes [114]. A similar understanding has also been adopted by Kant when writing “Endlich heißt das sowohl subjektiv als objektiv zureichende Fürwahrhalten das Wissen.” (cf. [25]; p. B 850/A 822), and has subsequently been widely acknowledged; see, for example, [115] or [116].

- Ayer, A.J. The Problem of Knowledge; Macmillan: London, UK, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer, L.E.J. Collected works; Heyting, A., Ed.; North Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- This characterization may also be considered a specification of what a cognitive system is. In some communities, it has become customary to denote such a system by an agent, be it human or not.

- This is the pure communication aspect associated with the dimensions of a sign. But such a communication setting may, in practice, be extended to include facets of the understanding of (at least parts of) the system’s properties, the type of validity accepted therein, etc. However, this is another matter and in principle subject to general hermeneutical reflections.

- The history of mathematics has shown that this is not necessarily the case. The proof of the independency of the continuum hypothesis from the axiom system ZFC, for example, has been disputed by the mathematical community.

- Troelstra, A.S.; van Dalen, D. Constructivism in Mathematics. An Introduction.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer, L.E.J. Proof that every full function is unifornly continuous (in Dutch). Koninkl. Nederl. Akad. Wetens. Proc. Sect. Sci. 1924, 27, 189–193. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, A.F. What is This Thing Called Science? 3rd ed.; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Capurro, R. Past, present, and future of the concept of information. TripleC 2009, 7, 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Platon, Theaitet. In [117].

- We have mentioned above that we prefer the term ‘conviction’ over ‘belief’. However, we use ‘belief’ in this section in accordance with the usual terminology in this field.

- Wieland, W. Platon und die Formen des Wissens; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Platon Menon. In [117].

- Gettier, E.L. Is justified true belief knowledge? Analysis 1963, 23, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cf. Aristotle’s theory of science in the second Analytic, which characterizes scientific concepts as those that are determined by definitions (see [118] Anal. post. II, 19, 100a f, Met. 1029b, Top. VI, 139a f).

- In Lotze [119], Par. 28, it is obvious that a pure “summation” of features turns out to be insufficient for conceptualizations, which is demonstrated by an example from mathematics. However, Lotze is not able to provide an intrinsic characterization of functional dependencies between concepts. It should be noted that one may start with a pure summation and nevertheless end up with a system comparable to first order predicate logic. This is shown by the Formal Concept Analysis approach (see, for example, Prediger [120]). However, this approach demonstrates how much technical effort is necessary to prove this equivalence, which is by no means easily seen.

- See also Lotze [119], §§28 and 110, who opposes the operator F(a,b,c,...) to a conceptualization given by a summation S=a+b+c+d... of attributes. However, Lotze is still far from providing a more precise specification of that operator at least outside mathematics. Only Frege’s conception of logic (along with Tarski’s definition of truth) may be seen as an implementation of this idea. However, it must be noted that Gabriel rightly hints at the most principal differences (see [119]; p. XXV).

- Cook Wilson, J. Statement and Inference; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Prichard, H. Knowledge and Perception; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.L. Sense and Sensibilia; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.L. Other minds. In Philosophical Papers; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1979; pp. 76–116. [Google Scholar]

- This is in contrast to Gödel, who stated that our logical intuitions like truth or concepts are contradictory (cf. [121]; p. 131). We emphasize the aspect of control rather than a principal avoidance of self-reference. For example, Cantor’s diagonalization method in mathematics (along with logical principles like the excluded third) constitutes a productive form of self-reference.

- Cauchy, A.-L. Cours d’analyse de l’École Polytechnique; Imprimerie Royale: Paris, France, 1821. [Google Scholar]

- Belhoste, B. Augustin-Louis Cauchy. A Biography; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, A.N.; Russell, B. Principia Mathematica; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1913; Volumes I-III. [Google Scholar]

- Tarski, A. Der Wahrheitsbegriff in den formalisierten Sprachen. Stud. Phil. Comment. Soc. Phil. Pol. 1935, 1, 261–405, (Polish original in [122].). [Google Scholar]

- Lenski, W. Gewusstes und Geteiltes. Zur Rolle der Logik zwischen Wissen und Wissenschaft. In Logik als Grundlage von Wissenschaft; Lenski, W., Neuser, W., Eds.; Universitäsverlag Winter: Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 89–141. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader, A.M. Toward a Theory of Library and Information Science; UMI Dissertation Information Service, Indiana University: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Another interesting approach is presented in Kanfer et al. [123] where “distributed knowledge processes” are discussed. The paper considers “embedded knowledge” which includes a shared understanding by group members. This conception is different from tacit knowledge: “embedded knowledge” is not ‘tacit’—just in the contrary, it is constructed collaboratively. Hence we find an extension of the concept of knowledge in alliances. It is then discussed how such forms of ‘knowledge’ may be made “mobile” outside their specific context. This question relates to the conditions under which external knowledge (being information) can be appropriated to constitute knowledge again. Moreover, the authors observe a process in groups that is similar to appropriation as discussed here. But there are also differences. The use of unprecise means, for example, such as metaphors were discussed to advance a shared understanding. Moreover, the role of misunderstandings is seen as a “necessary, and in some ways a potentially beneficial, aspect of any collaborative situation”. It would be interesting to see whether the analysis given in this paper could be transferred to the concept of “embedded knowledge”. Many basic concepts seem to have counterparts. ‘System’s property’, for example, could be related to “background needed to understand”, or “shared understanding” for ’appropriation’. This, however, constitutes separate work and will in any case be beyond the scope of this paper.

- Nyquist, H. Certain factors affecting telegraph speed. Bell. Syst. Tech. J. 1924, 3, 324–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, R.V.L. Transmission of Information. Bell. Syst. Tech. J. 1928, 7, 535–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.C. Age of Significance; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010ff; Available online: http://www.ageofsignificance.org/ (last accessed on 15 October 2010).

- Lachlan, A. A recurively enumerable degree which will not split over all lesser ones. Ann. Math. Logic. 1975, 9, 307–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descartes, R. Discourse on the method of rightly conducting the reason. In The Philosophical Works of Descartes; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 1931; Vol. 1, pp. 79–130. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasmith, Ch. Dictionary of Philosophy of Mind. Available online: http://philosophy.uwaterloo.ca/MindDict/ (last accessed on 15 October 2010).

- Kemerling, G. Philosophy Pages. Available online: http://www.philosophypages.com/index.htm (last accessed on 15 October 2010).

- Platon. Sämtliche Werke.; Hamburg, Germany, 1957f. [Google Scholar]

- Aristoteles. Aristotelis Opera; Bekker, I., Ed.; Academia Regia Borussica: Berlin, Germany, 1831–1870. [Google Scholar]

- Lotze, R.H. Logik. Erstes Buch. Vom Denken. New edition with an introduction by Gottfried Gabriel; Meiner Verlag: Hamburg, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Prediger, S. Kontextuelle Urteilslogik mit Begriffsgraphen. Ein Beitrag zur Restrukturierung der mathematischen Logik; Shaker Verlag: Aachen, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gödel, K. Russell’s mathematical logic. In The Philosophy of Bertrand Russell; Schilpp, P.A., Ed.; The Tudor Publishing Company: Evanstown, IL, USA, 1944; pp. 125–153. [Google Scholar]

- Tarski, A. Der Wahrheitsbegriff in den formalisierten Sprachen (Polish original). Compt. Rend. Séanc. Soc. Sci. Lettr. Varsovie, Classe III: Sci. Math. Phys. 1933, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Kanfer, A.G.; Haythornthwaite, C.; Bruce, B.C.; Bowker, G.C.; Burbules, N.C.; Porac, J.F.; Wade, J. Modeling distributed knowledge processes in next generation multidisciplinary alliances. Inf. Syst. Front. 2000, 2, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2010 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Lenski, W. Information: A Conceptual Investigation. Information 2010, 1, 74-118. https://doi.org/10.3390/info1020074

Lenski W. Information: A Conceptual Investigation. Information. 2010; 1(2):74-118. https://doi.org/10.3390/info1020074

Chicago/Turabian StyleLenski, Wolfgang. 2010. "Information: A Conceptual Investigation" Information 1, no. 2: 74-118. https://doi.org/10.3390/info1020074

APA StyleLenski, W. (2010). Information: A Conceptual Investigation. Information, 1(2), 74-118. https://doi.org/10.3390/info1020074