Abstract

Nearly one-third of the U.S. population provides unpaid, informal caregiving to a loved one or friend. Caregiver health literacy involves a complex set of actions and decisions, all shaped by communication. Existing definitions depict health literacy as individuals’ skills in obtaining, understanding, communicating, and applying health information to successfully navigate the health management process. One of the major problems with existing definitions of health literacy is that it disproportionately places responsibilities of health literacy on patients and caregivers. In this conceptual piece, we define and introduce a new model of Relational Health Literacy (RHL) that emphasizes the communicative aspects of health literacy among all stakeholders (patients, caregivers, providers, systems, and communities) and how communication functions as a pathway or barrier in co-creating health care and health management processes. Future directions and recommendations for model development are described.

1. Introduction

Dr. Platon asked Connie to step into the hallway, leaving Ben alone in his ER patient room. Dr. Platon told Connie that Ben was dying, that any pursuit of treatment was futile, and that his liver had completely stopped functioning. Connie was dismayed. They had originally come to the hospital that morning to be cleared for gall bladder removal the following day.

The narratives Connie and Ben shared illustrate the health literacy challenges that oncology family caregivers face in providing care for their loved ones and the need for a more collaborative approach in understanding health literacy and the role of communication.

Family caregivers of cancer patients play a significant role in the decision-making about care [1,2], yet their level of involvement is highly dependent upon their health literacy needs [3]. Nearly one-third of the U.S. population provides unpaid, informal caregiving to a loved one or friend, hereafter referred to as caregivers [4]. A cancer diagnosis is the fourth main reason for an individual to need a caregiver [5], and approximately 86% of cancer patients are accompanied by a caregiver to clinical visits [3]. Complex medical jargon, challenging physician-caregiver communication, an absence of collaboration, and omissions of educational support for the caregiver are a few of the many challenges faced by oncology family caregivers [6].

Caregiver health literacy involves a complex set of actions and decisions, all shaped by communication [7] and impacts the caregiver’s ability to collaborate and interact with patient, provider, community, and system. Barriers to health literacy negatively impact a caregiver’s access to cancer information, reduce her/his coping strategies, mute resources and support networks, and result in lower quality of life for the patient [8,9]. Compromised health literacy skills contribute to health disparities among ethnic and racial minorities or those caregivers with low socioeconomic status [10]. With the importance and struggle of the caregiver underscored, the language and ideas behind health literacy need explication.

2. Considering Current Definitions of Health Literacy

Connie was left to tell Ben about the change in surgical plans, and had to describe some version of what Dr. Platon told her. Ben became angry and insisted they leave the hospital. As they were walking down the hall, Dr. Platon intercepted them and spoke with both of them this time. He told Ben that he had some kind of cancer, and that he was referring them to a regional cancer center to be ‘diagnosed and staged’.

Health literacy is positively correlated with the use of preventive screening and the quality of healthcare individuals receive [11]. Dominating definitions depict health literacy as individuals’ skills in obtaining, understanding, communicating, and applying health information to successfully navigate the health management process [12,13,14]. With such definitions, scholars and practitioners have developed health literacy measures to identify individuals’ health literacy levels in order to better serve the needs of particular patient groups. However, existing measures do not holistically examine what health literacy is and how it influences health outcomes [15]. One of the major problems with existing definitions of health literacy is that it disproportionally places the responsibilities of health literacy on patients and caregivers [16,17], particularly those with low socio-economic status and low educational achievements [18].

However, significant research exploring a more carefully examined approach to health literacy is on the rise. Importantly, The European Health Literacy (HLS-EU) reviewed current definitions and models and developed an integrative conceptual model that strongly recognizes the role the individual and population plays in health literacy, but also the role of the system and its resources in creating health literacy barriers and points of access [19]. The work of the HLS-EU reveals the different perspectives on the problems of health literacy in Europe compared to the US, which still operates heavily on the individual skill and deficit paradigm. Edwards et al. [20] also make a unique case that health literacy is distributed throughout the networks surrounding the patient, and these distributions directly impact the individual’s management of care. The work of these researchers informs and inspires a new paradigm of health literacy understanding in which health literacy is co-constructed.

Health literacy involves not only caregivers’ and patients’ cognitive and functional skills, but also the collaborative efforts among patients, caregivers, healthcare organizations, healthcare providers, and communities [21,22]. This collaborative view of health literacy underscores the synergy among healthcare recipients, formal and informal healthcare providers, and resources from healthcare systems to reduce health literacy barriers and inequity in health. Moreover, another challenge with current health literacy studies is that researchers and practitioners tend to focus on individuals who are already accessing healthcare systems [21]. The deficiencies of existing health literacy models reinforce the need for a comprehensive conceptual model reflecting the transactional nature of interactions among patients, caregivers, providers, systems, and communities [21,23] both in and out of healthcare systems [21].

Researchers in the late 1990s focused on context-specific skills of the individual, such as reading appointment slips and prescribed treatment regimens [16]. Early models of health literacy featured individuals’ literacy skills, health outcomes, and costs [12]. Baker [24] presented another model defining health literacy with two major domains. The first domain addresses individual capacities, such as reading fluency and prior knowledge, and the second domain examines a person’s ability to understand both written and spoken information. Paasche-Orlow and Wolf [25] viewed health literacy and health outcomes as context-sensitive, which depends on the relationship between individuals and the healthcare systems. Parnell [26] presented a conceptual model that depicts individuals’ health literacy as fluid and context-specific and is based on the impacts created by individuals, healthcare providers, and systems.

Different from these models in which researchers called both patients and their caregivers “individuals”, Yuen et al. [27] developed a multidimensional model of health literacy by presenting six domains that influence caregivers’ health literacy. Yuen et al. [27] emphasized that health literacy involves both personal and relational elements along with healthcare systems, healthcare providers, and communities.

Inspired by Yuen and colleagues’ [27] conceptual model that emphasizes the collaborative efforts of those who professionally and informally provide care, those who receive care, and the healthcare systems providing resources, we develop a conceptual model of relational health literacy (RHL) that emphasizes the communicative aspects of health literacy among all stakeholders (patients, caregivers, providers, systems, and communities) and how communication functions as a pathway or barrier in co-creating the health management process. What follows is a description of this early conceptual effort and research support for its creation.

3. Conceptualizing Relational Health Literacy

Commonly, health literacy is relegated to the individual and their skills in obtaining, reading, understanding, and using health information [7], all of which shape communication behaviors [3]. Caregivers still report facing challenges in getting information, feeling isolated, and find there is minimal educational support after appointments for loved ones [28]. Caregiver anxiety can impede the ability to understand information about cancer, leaving caregivers feeling further stressed and overextended [29]. Anxiety about communication with oncologists further contributes to caregiver distress and lowered quality of life [30]. Confused and isolating communication between cancer providers and caregivers often obstructs the understanding of pharmaceutical instructions [31], and can result in poor adherence to analgesic regimens that leave patient pain undertreated [32,33].

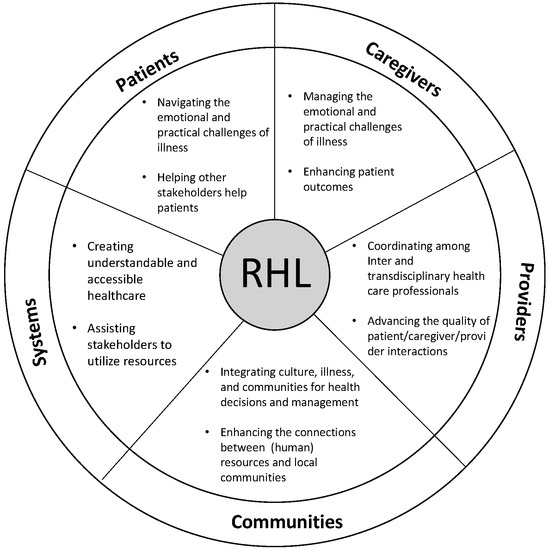

We feature the experience of Connie and Ben in the US healthcare system used in previous caregiver research leading to this conceptual work with their story de-identified, upon receiving an approval from the appropriate Institutional Review Board [34,35]. Their journey reveals the complexity of health literacy in the context of oncology, and the many channels of incomplete, conflicting, and stressful information bombarding the caregiver. We follow Connie’s experience in this unfolding case to demonstrate the weight of multiple stakeholders in the creation of barriers and pathways to health literacy. What follows is an articulation of these stakeholder groups and their role in co-creating health literacy for the oncology family caregiver. The consideration of stakeholder domains in health literacy leads us to consider the new conceptual idea of relational health literacy, see Figure 1. Unique to this conceptual model is the role of communication in serving as a barrier or pathway to improved and co-created health literacy. The five domains of the model, patients, caregivers, providers, communities, and systems, will be described in light of their communication role in co-created relational health literacy.

Figure 1.

Relational Health Literacy Conceptual Model.

Ben was diagnosed at the regional cancer center with adenocarcinoma of unknown primary site, an aggressive metastatic cancer. It was Stage IV. He had not eaten for 7 days and was struggling to drink. Unlike Dr. Platon, oncologists there did not offer suggestions about abandoning treatment, and instead referred him on to a comprehensive cancer center in southern Texas. This would mean a 10-hour grueling car ride.

3.1. Patients

Patients are the individuals who receive healthcare, directly experience the treatments, and face the health outcomes. When managing health, patients’ health literacy plays an important role in the various occasions when they make decisions; that is, where to look for health-related information, what to trust and to what extent, to whom they share information about the issues and how, when to see healthcare providers, which healthcare providers to see, and what treatments are selected. Various factors, including patients’ cognitive, linguistic, and numeracy skills, cultural beliefs and/or expectations about healthcare, and interactions with healthcare providers affect patients’ health literacy and their health outcomes [11,36,37,38]. Other factors, such as emotional distress and distrust toward health systems and/or health providers, can influence patients’ health outcomes regardless of their level of individual health literacy [39,40].

Facing a diagnosis with major health issues causes a tremendous amount of anxiety and uncertainty that can disturb not only a patient’s cognitive decision-making abilities but also their basic physical health. Moreover, revealing low (health) literacy or asking for assistance to understand the information causes patients to experience shame, even when they have high health literacy and/or educational achievement [41]. Researchers reported that patients’ distrust toward healthcare providers and emotional distress, whether or not they are related to the health issues in question, prevents patients from taking recommended actions even when patients have high health literacy [40,42].

Communication can enhance patients’ sense of “therapeutic alliances” [43] with other stakeholders (individuals categorized in healthcare providers, caregivers, communities, and systems), which can alleviate the emotional distresses, increase trust in healthcare providers and healthcare systems, and expand or at least sustain patients’ motivations and skills to gather credible information to make appropriate decisions for their health. Patients’ active communication with healthcare providers, in return, can assist healthcare providers to facilitate patient-centered care [44].

Connie wanted Ben to live and to receive treatment. She had two disparate diagnoses and descriptions from providers about how Ben could navigate this illness, and was eager to act on the second version—treat and survive. Once in south Texas, Ben continued to worsen. He was too weak to sit in the clinic waiting room before his appointment, and Connie went alone instead with Ben’s records.

3.2. Caregivers

In 2018, the National Alliance for Caregiving report on “Caregiving in the US” recognized the exigent need for caregiver provisions as a national public health issue. Unpaid, untrained, informal family/friend caregivers provide the backbone of healthcare delivery in the United States. They are pivotal in decision-making, treatment planning, place of care decisions, and intervention acquisition and withdrawal. Caregivers take a variety of roles in assisting patients’ journeys in health management. Like Connie, caregivers are often tasked with sharing news of a diagnosis with the patient and others—A multifaceted role that involves deciding (1) what information should be shared, (2) when to share it, and (3) how the news should be shared [45]. Caregivers are in need of communication skill building, as their interactions are a key factor in enacting support and decisions for good patient outcomes [46,47].

Caregivers face an increased need for information related to caregiving tasks as well as supportive tools for developing coping and hands-on medical caretaking skills [48]. When caregivers are responsible for the tasks that can affect their loved one’s lives (i.e., cleaning a ventricular assist device), the caregivers’ skills to complete the task correctly can be largely affected by pressure and emotional distress [49]. Caregivers provide support and aid that varies from observable practices (i.e., arranging transportation) to complex support (i.e., communicating health information). As part of complex caregiving tasks, caregivers must coordinate medications from different providers across care settings [50]. Other challenges include understanding and recognizing the names, functions, and side effects of medicines [50]. Caregiver communication mediates coping, positively impacts the stress experienced in illness [51], increases the caregiver’s ability to assist the patient with safe and effective home medication use [52], and reduces the risk of hospital admission or readmission for the patient [53].

Connie met with Dr. Brown, a gastrointestinal oncologist. After a great deal of resistance, Dr. Brown acquiesced to Connie and ordered a round of chemotherapy for Ben. The infusion would start that evening if Connie could complete the payment for it before billing closed at 5 pm.

3.3. Providers

Healthcare providers are the stakeholder group commonly regarded as having high health literacy; that is, they hold the information and skills necessary for giving diagnoses, explaining the information about symptoms and treatments, and guiding patients and caregivers to utilize appropriate resources. However, RHL reframes that assumption and holds all stakeholders responsible for creating barriers and limitations for self and other stakeholder groups. As such, using complex and impenetrable language or information contributes to overall low health literacy across stakeholders [26]. Despite different types of involvements with patients and their family members, providers are not always aware of the patients’ and caregivers’ needs for the information related to diagnoses and treatment options, as well as the type of supports and resources [54] they can access. Many healthcare providers, who often enter the healthcare field with a strong passion for helping others, often experience the dilemma of being caught between their desire to meet patient/caregiver needs and the constraints imposed by healthcare systems [41].

In addition to increasing healthcare providers’ awareness and understandings of health literacy, communication can help mitigate difficulties and barriers across stakeholders. Promoting healthcare providers’ communication skills can not only enhance patients’ participation in decision-making but also increases the likelihood that patients/caregivers understand treatment procedures and follow the recommended regimens [55,56].

In a span of less than 10 days, Connie and Ben had entered a new universe of cancer and fear. The first chemo infusion ended early, as Ben became violently ill. He took to his bed at the hotel, and Connie waited for improvements or their next appointment, whichever might come first. They knew no one in South Texas, and they knew no one with cancer. Their hotel was far from a grocery store as it was located in downtown Houston, and Ben was too sick to be left alone.

3.4. Communities

Various types of communities exist among the stakeholders, which both prohibit and facilitate the process of healthcare and management. Local communities, illness communities, and specific cultural groups are a few examples of community in RHL. Fatalistic perspectives shared in a cultural community, for example, would prevent individuals from actively seeking treatment regardless of their health literacy level [57]. On the other hand, belonging to a certain group of people (i.e., illness community) allows individuals with low health literacy to readily access healthy options without understanding the detailed information and/or taking individualized actions [58,59].

For patients and caregivers, their interactions and involvement within local communities allow individuals to develop higher skills in identifying resources and information [60]. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention has identified the power of community in their research on social network strategies, in which community-based intervention development has proven far more successful than healthcare organizations at providing care interventions for HIV and other chronic illnesses [61]. Health literacy can be distributed and expanded through communication among social communities, and the individuals who distribute health literacy tend to become more health literate [20]. The significant reach and credibility of communities and their health literacy is a burgeoning area of research, exemplified by new work in environmental health literacy, which explores community health outcomes and risk [62].

Ben never got out of bed after his one and only chemotherapy treatment. Connie had completed the payment for $12,000.00 using their bank card. They were between health insurances and had no coverage. Both Connie and Ben were wealthy, and were in a unique position to pay outright for the single treatment. Despite their wealth, Ben and Connie were stuck in a hotel across from the hospital, and the only place to go for help was the ER. After three days of watching Ben writhe in pain, unable to take liquids or eat, Connie chartered a private plane home to Oklahoma. Once there, she initiated hospice care on her own, without the support of Dr. Platon, their local physician.

3.5. Systems

Healthcare organizations and their operations are included in the systems domain of the RHL model. The Plain Writing Act of 2010 and Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) i.e., [63], introduced the requirement of understandable written and spoken communication in all U.S. healthcare systems. These guidelines recommend the use of plain language when communicating with patients and family members by stressing the consequences of low health literacy [64]. Along with the Department of Health and Human Services Plain Writing Act and the Federal Plain Language Guidelines [63], the plain language categories developed by Kaphingst et al. [65] guide health literacy assessment, analysis, and the creation and development of health-related materials. The plain language index includes: (a) A reading level no higher than sixth grade, (b) use of the active voice, (c) use of the second person to address patients, (d) limited use of medical jargon, (e) brief sentences, and (f) easy to understand phrasing.

Wayfinding and signage, whether electronic or on-site, are partners to plain language work. Without communicative pathways for patients and caregivers, provider contact can remain elusive and effective care can be delayed or missed entirely. Health literacy is impacted by various factors, including limited English proficiency, language discordance, use of interpreters, availability of educational materials in other languages, healthcare system resources, and provider preparation and support within a system [27,66,67,68]. Despite governmental efforts to mitigate cultural and linguistic gaps across systems, health literacy challenges remain in large part because of limited resources and deficient skills to implement change [69,70].

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

A central catalyst for this early work in Relational Health Literacy is the struggle of the family caregiver. The complexity of the caregiver’s work is most accurately understood in light of the stakeholder contributions to health literacy. A key focus of RHL work going forward will involve caregiver training and the rigorous development of resources and tools for use by community, providers, and systems.

Recommendations for future work on RHL will include the following initiatives.

Develop the conceptual model of RHL. As RHL grows, we will explore targeted interventions for each stage of model development. Using existing instruments from related fields, it will be important to quantify the domains of RHL. Ideally, this model should account for health literacy and explain how its stakeholders co-create health literacy.

Employ RHL as a resource for all stakeholders. Disseminating RHL to stakeholders in the form of research and relationship building will be central to integrating the domains and what we know about their impact on one another. Education for stakeholders should extend beyond a description of this conceptual model, and directly engage partnerships and suggested communication modalities to mitigate health literacy barriers cultivated across stakeholder domains. Targeting education modules and points of learning for the five domains will enable tool development and alteration of the entrenched practices and care approaches that reduce effective communication across the five domains.

Conduct RHL research. Expanding our efforts to address gaps in knowledge and bring communication and its role to the forefront of health literacy will guide future research projects. Investigations will include furthering our understanding of the process of RHL across domains in order to improve it, develop and test measures that inform RHL, measure health behavior change based on co-created health information distribution, and identify interventions that will improve our understanding of the complexities and solutions to low RHL.

The five stakeholder domains identified in RHL impacted Connie and Ben significantly. We can learn from their struggle, and from Connie’s journey in decision-making and care on behalf of her patient-spouse. The caregiver is, in many respects, the most vulnerable stakeholder in the entire model. They are situated at the crosshairs of pressure, high stakes, responsibility, and low preparedness in ways that other stakeholders are not. For these reasons, the oncology caregiver provided the entry point into our efforts to define and explore the RHL model in its initial stage.

Author Contributions

J.V.G. and S.T. conceived and designed this conceptual project. Both authors substantially contributed research across all aspects of the paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Laidsaar-Powell, R.; Butow, P.; Bu, S.; Charles, C.; Gafni, A.; Fisher, A.; Juraskova, I. Family involvement in cancer treatment decision-making: A qualitative study of patient, family, and clinician attitudes and experiences. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.W.; Cho, J.; Roter, D.L.; Kim, S.Y.; Yang, H.K.; Park, K.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, H.Y.; Kwon, T.G.; Park, J.H. Attitudes toward Family Involvement in Cancer Treatment Decision Making: The Perspectives of Patients, Family Caregivers, and Their Oncologists. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laidsaar-Powell, R.; Butow, P.; Boyle, F.; Juraskova, I. Managing challenging interactions with family caregivers in the cancer setting: Guidelines for clinicians (TRIO Guidelines-2). Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallup Healthways Wellbeing Survey More than One in Six American Workers Also Act as Caregivers. Available online: http://www.gallup.com/poll/148640/One-Six-American-Workers-Act-Caregivers.aspx (accessed on 2 April 2017).

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Families Caring for an Aging America; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, M. What Family Caregivers Need from Health IT and the Healthcare System to be Effective Health Managers. Available online: http://www.connectedhealthresources.com/What_Family_Caregivers_Need_from_Health_IT_and_the_Healthcare_System_to_be_Effective_Health_Managers_Sterling_December_2014_v2.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- Smedley, B.D.; Stith, A.Y.; Nelson, A.R. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Available online: https://www.nap.edu/read/12875/chapter/1 (accessed on 1 March 2016).

- Gibson, J.; Snodgrass, J. The relationship of health literacy to the stress level of informal caregivers. Int. J. Literacies 2014, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Sherwood, P.R. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Am. J. Nurs. 2008, 108, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion; National Academics: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- The Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020: Phase I Report, Recommendations for the Framework and Format of Healthy People 2020. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/PhaseI_0.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2018).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Learn about Health Literacy. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn/ (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- Haun, J.N.; Valerio, M.A.; McCormack, L.A.; Sørensen, K.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K. Health literacy measurement: An inventory and descriptive summary of 51 instruments. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 302–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. Health literacy: Report of the council on scientific affairs. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1999, 281, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutilli, C.C.; Bennett, I.M. Understanding the health literacy of America results of the National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Orthop. Nurses 2009, 28, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, P.; DiNenno, E. Communities in Crisis: Is There a Generalized HIV Pidemic in Lmpoverished Urban Areas of the United States? Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/poverty.html (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- Sorenson, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, B. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, M.; Wood, F.; Davies, M.; Edwards, A. ‘Distributed health literacy’: Longitudinal qualitative analysis of the roles of health literacy mediators and social networks of people living with a long-term health condition. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 1180–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterham, R.W.; Hawkins, M.; Collins, P.A.; Buchbinder, R.; Osborne, R.H. Health literacy: Applying current concepts to improve health services and reduce health inequalities. Public Health 2016, 132, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, W.S.; Gaysynsky, A.; Persoskie, A. Health literacy and communication in palliative care. In Textbook of Palliative Care Communication; Wittenberg, E., Ferrell, B.R., Goldsmith, J., Smith, T., Ragan, S.L., Glajchen, M., Handzo, G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Young, A.J.; Stephens, E.; Goldsmith, J.V. Family caregiver communication in the ICU: Toward a relational view of health literacy. J. Fam. Commun. 2017, 17, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.W. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 878–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Wolf, M.S. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am. J. Health Behav. 2007, 31, S19–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parnell, T.A. Health Literacy in Nursing: Providing Person-Centered Care; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yuen, E.Y.N.; Dodson, S.; Batterham, R.; Knight, T.; Chirgwin, J.; Livingston, P. Development of a conceptual model of cancer caregiver health literacy. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2016, 25, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Alliance for Caregiving. From Insight to Advocacy: Addressing Family Caregiving as a National Public Health Issue; National Alliance for Caregiving: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, J.; Lee, C.J.; Jensen, J.D. Correlates of cancer information overload: Focusing on individual ability and motivation. Health Commun. 2016, 31, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Given, B.A.; Sherwood, P.; Given, C.W. Support for caregivers of cancer patients: Transition after active treatment. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 2011, 20, 2015–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, D.T.; Berman, R.; Halpern, L.; Pickard, A.S.; Schrauf, R.; Witt, W. Exploring factors that influence informal caregiving in medication management for home hospice patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2010, 13, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayahara, M. Pain medication management by hospice caregivers. J. Pain 2011, 12, P27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miaskowski, C.; Dodd, M.J.; West, C.; Paul, S.M.; Tripathy, D.; Koo, P.; Schumacher, K. Lack of adherence with the analgesic regimen: A significant barrier to effective cancer pain management. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 4275–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittenberg Lyles, E.; Goldsmith, J.; Ragan, S.; Sanchez-Reilly, S. Dying with Comfort: Family Illness Narratives and Early Palliative Care; Hampton Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, J.; Wittenberg Lyles, E.; Shaunfield, S.; Sanchez-Reilly, S. Unfolding case responses to a palliative appropriate patient: A reflective practice dilemma when the case does not fit the algorithm. Am. J. Hospice Palliat. Med. 2011, 26, 236–241. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, D.M.; Larson, J.L.; Zikmund-Fisher, B.J. Associations between health literacy and preventive health behaviors among older adults: Findings from the health and retirement study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sentell, T.; Braun, K.L. Low health literacy, limited English proficiency, and health status in Asians, Latinos, and other racial/ethnic groups in California. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, A.Y.M.; Bo, A.; Hsiao, H.Y.; Wang, S.S.; Chi, I. Health literacy issues in the care of Chinese American immigrants with diabetes: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, R.O.; Chakkalakal, R.J.; Presley, C.A.; Bian, A.; Schildcrout, J.S.; Wallston, K.A.; Barto, S.; Kripalani, S.; Rothman, R. Perceptions of provider communication among vulnerable patients with diabetes: Influences of medical mistrust and health literacy. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schinckus, L.; Dangoisse, F.; Van den Broucke, S.; Mikolajczak, M. When knowing is not enough: Emotional distress and depression reduce the positive effects of health literacy on diabetes self-management. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajah, R.; Ahmad Hassali, M.A.; Jou, L.C.; Murugiah, M.K. The perspective of healthcare providers and patients on health literacy: A systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative studies. Perspect. Public Health 2018, 138, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, P.J.; Nakamoto, K. Health literacy and patient empowerment in health communication: The importance of separating conjoined twins. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 90, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Street, R.L., Jr.; Makoul, G.; Arora, N.K.; Epstein, R.M. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, C.L.; Coran, J.J.; Hagen, M.G. Revisiting patient communication training: An updated needs assessment and the AGENDA model. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 88, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewing, G.; Ngwenya, N.; Benson, J.; Gilligan, D.; Bailey, S.; Seymour, J.; Farquhar, M. Sharing news of a lung cancer diagnosis with adult family members and friends: A qualitative study to inform a supportive intervention. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrell, B.; Wittenberg, E. A review of family caregiving intervention trials in oncology. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northouse, L.L.; Katapodi, M.C.; Song, L.; Zhang, L.; Mood, D.W. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2010, 60, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, N.C.; Demiris, G. The roles of telehealth tools in supporting family caregivers: Current evidence, opportunities, and limitations. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2017, 43, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilger, D. The Emotional Health Literacy Block. Available online: https://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2013/11/emotional-health-literacy-block.html (accessed on 14 May 2018).

- Schumacher, K.L.; Plano Clark, V.L.; West, C.M.; Dodd, M.J.; Rabow, M.W.; Miaskowski, C. Pain medication management processes used by oncology outpatients and family caregivers part II: Home and lifestyle contexts. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 48, 784–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, B.S.; Miaskowski, C.; Given, B.; Schumacher, K. The cancer family caregiving experience: An updated and expanded conceptual model. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2012, 16, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roter, D.L.; Narayanan, S.; Smith, K.; Bullman, R.; Rausch, P.; Wolff, J.L.; Alexander, G.C. Family caregivers’ facilitation of daily adult prescription medication use. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodakowski, J.; Rocco, P.B.; Ortiz, M.; Folb, B.; Schulz, R.; Morton, S.C.; Leathers, S.C.; Hu, L.; James, A.E., 3rd. Caregiver integration during discharge planning for older adults to reduce resource use: A metaanalysis. J. Am. Geriat. Soc. 2017, 65, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robotin, M.C.; Porwal, M.; Hopwood, M.; Nguyen, D.; Sze, M.; Treloar, C.; George, J. Listening to the consumer voice: Developing multilingual cancer information resources for people affected by liver cancer. Health Expect. 2017, 20, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huntington, B.; Kuhn, N. Communication gaffes: A root cause of malpractice claims. Proc. (Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent.) 2003, 16, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agostino, T.A.; Atkinson, T.M.; Latella, L.E.; Rogers, M.; Morrissey, D.; DeRosa, A.P.; Parker, P.A. Promoting patient participation in healthcare interactions through communication skills training: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.Y.; Vang, S. Barriers to cancer screening in Hmong Americans: The influence of health care accessibility, culture, and cancer literacy. J. Commun. Health 2010, 35, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, M.C.; Machtinger, E.L.; Wang, F.; Schillinger, D. Health literacy and anticoagulation-related outcomes among patients taking warfarin. JGIM 2006, 21, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, Y.; Hohl, S.D.; Ko, L.K.; Rodriguez, E.A.; Thompson, B.; Beresford, S.A. Understanding the patient-provider communication needs and experiences of Latina and non-Latina White women following an abnormal mammogram. J. Cancer Educ. 2014, 29, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rikard, R.V.; Thompson, M.S.; McKinney, J.; Beauchamp, A. Examining health literacy disparities in the United States: A third look at the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of Social Networks to Identify Persons with Undiagnosed HIV Infection—Seven U.S. Cities, October 2003–September 2004. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5424a3.htm (accessed on 2 April 2018).

- Finn, S.; O’Fallon, L. The emergence of environmental health ltieracy—From its roots to its future potential. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Federal Drug Administration Federal Plain Language Guidelines. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/PlainLanguage/UCM346279.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Nouri, S.S.; Rudd, R.E. Health literacy in the “oral exchange”: An important element of patient-provider communication. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaphingst, K.A.; Kreuter, M.W.; Casey, C.; Leme, L.; Thompson, T.; Cheng, M.-R.; Jacobsen, H.; Sterling, R.; Oguntimein, J.; Filler, C. Health literacy INDEX: Development, reliability, and validity of a new tool for evaluating the health literacy demands of health information materials. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, E.L.; Doorenbos, A.Z.; Javid, S.H.; Haozous, E.A.; Alvord, L.A.; Flum, D.R.; Morris, A.M. Shared decision-making for cancer care among racial and ethnic minorities: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, e15–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costas-Muniz, R.; Sen, R.; Leng, J.; Aragones, A.; Ramirez, J.; Gany, F. Cancer stage knowledge and desire for information: Mismatch in Latino cancer patients? J. Cancer Educ. 2013, 28, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campesino, M.; Saenz, D.S.; Choi, M.; Krouse, R.S. Perceived discrimination and ethnic identity among breast cancer survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2012, 39, E91–E100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youdelman, M.K. The medical tongue: U.S. laws and policies on language access. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabler, R. What we’ve got here is failure to communicate: The Plain Writing Act of 2010. J. Legis. 2013, 40, 280–323. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).