Abstract

In the first part of this paper, we have introduced a novel theoretical approach to mating dynamics, known as Tie-Up Theory (TU). In this second part, in the context of the bio-cultural approach to literature, that assigns to fictional narratives an important valence of social cognition, we apply the conceptual tools presented in the first part to the analysis of mating-related interaction dynamics in some blockbuster Hollywood movies from WWII to today. The interaction dynamics envisioned by our theory accurately reflect, to a significant level of detail, the narrative development of the movies under exam from the viewpoint of the mating dynamics of the couple of main characters, accounting for the specific reasons that lead them to react to certain situations via certain behaviors, and for the reasons why such behaviors lead to certain outcomes. Our analysis seems thus to bring some further legitimacy to the bio-cultural foundation of the narrative structure of the movies that we analyze, and moreover to the idea that it is possible to ‘inquire’ characters about their choices according to the narratological-experimental lines suggested by some proponents of the bio-cultural approach.

Because authors of fiction are free to construct narrative and characters unencumbered by the irrelevant detail that makes it hard to pierce real-life emotional events, we can read plays and novels as the closest thing to a controlled experiment involving high-stakes human emotions.Elster [1] (pp. 107–108)

1. Introduction

In the first part of this paper [2] we have presented a new conceptualization of heterosexual mating as a dynamic process where the sexual and emotional dimensions interact in subtle, complex ways. In particular, our approach is based upon the recognition of a fundamental asymmetry between the sexes as to the role of sexual vs. emotional signals in promoting, in a given subject, a short- vs. long-term mating orientation—of course concurrently with a rich constellation of other kinds of factors [3]. The dynamic interaction schemes that we have introduced are original and are not found in the existing literature. However, their main implications cannot be regarded as unexpected solutions to issues that have drawn constant attention in scientific as well as popular debates [4]. Our theoretical constructs are best understood as rationalizations of fragmented bits of knowledge and experience about the social cognition of mating. Such bits have often been ingrained into human cultural repertoires, but seldom fully recognized for what they are. In this second part, we will show how some effective dynamic solutions to the problem of long-term mating in heterosexual couples have been codified as a sort of structural invariant in a certain class of romantic fictional narratives. Far from being rare, these narratives are commonly found both in literature and cinema, and can easily be exemplified.

To state that literary or movie narratives may provide some form of corroboration of a psychological model may sound bizarre. However, one of the most interesting developments of literary theory in the last years has been the claim that, from an evolutionary perspective, fictional narratives can be considered as a sophisticated strategy of social learning which enables individuals and groups to transmit, and to take advantage from, experiences they did not directly experiment with [5]. As [6] puts it, fictions are a form of simulation of social experience with considerable adaptive value, which can be inter-subjectively and inter-generationally transmitted. The most systematic applications of this intergenerational form of learning from experience are found in the sphere of social cognition [7], and particularly in the human capacity to develop a theory of mind that allows to understand and foresee the behaviors of other individuals and groups in certain social situations [8]. The mating process is one of the social situations where a theory of mind, and especially the ability to understand the intentions, desires and beliefs of the other, becomes an indispensable tool for the building of a stable bond among the subjects involved [9]. It is thus no surprise that mating-related issues and circumstances have been one of the most recurrent and characteristic elements of human narratives of any epoch, culture, and latitude [10]. Some authors dare to claim that the systematic analysis of the basic elements of fictional narratives shows how the accomplished mating of the main characters, as the result of the overcoming of any sort of obstacles and adverse intentions, represents the most common, and somehow necessary, outcome of many different typologies of stories which are found in the most diverse historical and socio-cultural contexts [11].

The mating problem is therefore not only relevant from the viewpoint of narratives as a form of social learning [12], but can even be considered as one of the model situations which have shaped social learning practices themselves, as a response to the social cognition issues it raises [13]. The mating process therefore provides strong incentives to socio-cognitive human development [14]. A key implication of the narrative perspective on heterosexual mating is thus that an accomplished couple (that is, a stable one, resilient to external circumstances) is made possible by physically and emotionally apt partners, well developed from the psycho-social viewpoint, and willing to pursue their couple goals despite the occurrence of unfavorable external conditions [15]. If interpreted as an injunction, and thus as a narrow, instrumental a contrario imperative, the narrative characterization of the ‘ideal’ (heterosexual) couple naturally lends itself to dangerous and potentially pathogenic distortions [16]. Of major concern, for instance, are phenomena such as the stigmatization of singles [17], people with disabilities [18] or of couples with LGBT, i.e., non-standard-heterosexual, orientations [19]. An analysis of LGBT mating dynamics from a narrative perspective is beyond the scope of this paper, although it clearly stands as a topic of great social relevance. Our emphasis on the mating process of the heterosexual couple, which is the specific conceptual domain of our theoretical approach, does not intend in any respect to imply a hegemonic or preferential vision of heterosexual relations within the broader sphere of human sexual and affective relations.

The socio-cognitive valence of fictional narratives largely depends on their capacity to balance elements of idealization and realism within the narrative rendition of the mating interaction [20]. Consequently, in the context of narrative approaches to the resilience of real couples, the shared construction of ‘we stories’, where such balance is explicitly negotiated by partners, acquires a prescriptive value [21]. Vice versa, the shared access within the couple to a fictional narrative universe has a positive impact on the creation of the appropriate conditions for an effective negotiation [22]. The narrative construction of marital harmony may therefore perform a role of social exemplification, whose effective replication and diffusion may in turn be interpreted as the production of a public good [23]. What gives interest to the story, however, is not the mere fact that the couple is successfully formed and persists over time, but rather the account of the actual process through which this becomes possible. Stories break down such process into the steps through which the lead characters learn to define and structure themselves as the partner’s ‘other half’ [24]. This is the nature of the knowledge upon which the narrative dimension of social learning ultimately focuses [25]. As shown by [26], it then becomes possible to regard romantic love as an evolved commitment device that makes couple bonding and stable mating possible. In so doing, it provides an incentive to joint parental investment in offspring rearing and, even more fundamentally, to the evolution of social intelligence and cooperation.

In this paper, we will analyze some examples of a certain instance of fictional narrative, the cinematic one, and more specifically a small sample of American romance movies from WWII up to the previous decade. The reason behind our choice is that Hollywood romance movies have played a major role in shaping the global imaginary of romantic relationships and couple formation [27]. The socio-cognitive relevance of movies, and specifically of Hollywood productions, which are skillfully designed to appeal to vast, inter-cultural audiences, is the combination of at least two factors. First, human beings spontaneously tend to organize in narrative form the cognition of their romantic relationships [28]. Second, movie narratives, in the context of contemporary popular culture, prove to be especially accessible and intelligible as compared to homologous literary forms [29]. Due to their social simulation function, fictional narratives may be ‘twice as true as fact’ [6], and recent research in the neuroscience of fiction appreciation reveals that neural activation patterns while accessing fictional narratives correspond to constructive simulation activity, as opposed to the ex-post action-based reconstruction of events that characterizes non-fictional ones [30]. Moreover, experimental evidence suggests that humans actively and naturally make use of fictional inputs to extract useful knowledge for the interpretation of real facts [31]. Through their parsimonious representation of the fundamental steps of the mating process, romantic fictional narratives may therefore provide a socially validated account of the crucial components of the most effective strategies that are characteristic of each sex [32].

It is important to underline how not all fictional narratives have the same social cognition value, and specifically that not all cinematic narrations that fall within the rubric of the romance are equally rich with significant elements in this regard [33]. In the first place, literary characters provide a richer basis for social cognition than more stereotyped popular characters [34]—an intuition that has been experimentally corroborated [35]. Moreover, even in case of powerfully sketched characters, it is necessary to fix attention upon narratives where the mating process is the central theme, rather than a marginal or instrumental one with respect to the real focus of the story, albeit such centrality may not always be obvious or explicit [36]. The knowledge resources that are of help for a better understanding of the mating process are not necessarily the product of the psychological insight and of the ingenuity of the screenwriters, but rather represent a sort of implicit narrative grammar that screenwriters ought to abide by if they want to build a credible story [37]. This is the reason why we find certain structural analogies between cinematic narratives from different periods, which are notably different for the most part of other relevant aspects, including implicit social norms and reference values, or the nature and content of sexual roles and stereotypes. In other words, cinematic narratives are not a blueprint of all-purpose troubleshooting recipes for mating issues, but rather an open-ended, reasoned repertoire of behavioral patterns in relevant social situations, crystallized into narrative structures [38].

If all such knowledge is easily accessible, and entrenched in human cultures, why mating and couple dynamics issues keep on baffling individuals and societies with their complexities? This is in fact a key theme in narrative-based social learning [39]. Being able to learn from the circumstances of fictional characters and situations is an important potential source of evolutionary advantage [40], but the social cognition value of fictional knowledge constantly co-evolves with the social environment itself. What remains stable is our instinctive reliance toward fiction as a gateway of exchange between the self and the social reality. The well documented, cross-cultural capacity of fiction to elicit powerful, authentic individual and collective emotional responses is a clear certification of its relevance as a socio-cognitive learning platform [41]. If the fictional nature of stories might imply at times some psychological distancing [42], the profound link that is established between the acquisition of social abilities and narrative competences since early childhood makes it natural for humans to consider fiction as an externalization of consciousness [43]. The tension between narrative ‘enchantment’ vs. ‘disenchantment’ may be solved differently in different social contexts. For instance, post-modern societies may have grown skeptical as to the idea that narratives are linked to some form of stable, widely shared reality beyond the sphere of a language game anchored to a specific social context [44]. The idea that narratives, and more generally the arts [45], are shaped by their adaptive value, moreover, obviously conflicts with the postmodern scholarly perspective [46], which fiercely disputes it. However, the increasing, concordant evidence of the subtle interplay between fictional narratives and human emotion [47] and cognition [48] in the shaping of individual and social realities makes, in our opinion, a powerful case for the emerging dialogue among literary disciplines, psychology and the social and biological sciences as a promising new frontier of theoretical and empirical research [49].

In this paper, we will show how some of the main implications of the theoretical model that we developed in the first part [2], in particular with reference to the most effective strategies for the creation and consolidation of the couple, are reflected to an intriguing degree of accuracy into the narrative dynamics of certain Hollywood romances. We do not think that the domain of application of our model is limited to mainstream cinematic narratives from WWII to the present day, although such period represents an interesting benchmark in many respects [50]. We expect to find similar results also considering a geographically and historically wider range of examples of literary and cinematic narratives, and we intend to develop this extended analysis in future research. However, within the context of the present paper, we feel that our results may represent a meaningful enough first step to spark fresh interest toward the analysis of mating and couple dynamics issues through the lens of an interdisciplinary synthesis between psychology and the humanities. We thus mean to probe our behavioral approach at a narratological as well as at an experimental level, and possibly to devise new types of joint narratological-experimental [51] and narratological-neuroscientific tests (building upon promising results such as those of [52]).

After having discussed in some more detail the relationship between fictional narratives and social cognition in Section 2, in Section 3 we discuss how the mating process constitutes a basic theme of fiction. In Section 4 we re-introduce, for the reader’s convenience, the basic tenets of our theoretical approach presented in [2]. In Section 5 we present a new development of the theoretical framework, that further builds on [2] and is useful for the analysis that follows. In Section 6 we finally analyze a sample of cinematic narratives with the tools previously deployed. Section 7 presents some concluding remarks.

2. Fictional Narratives and Social Cognition: A Bio-Cultural Approach

The advantage of an approach that focuses upon fictional narratives is that it allows to test, however indirectly, behavioral responses in more complex, variegated and ‘natural’ contexts than usually possible in laboratory settings [53]. The two options, though, are not mutually exclusive, and could and should both be explored in their different capacities whenever possible [54]. Laboratory experimentations are necessarily centered upon extremely specific, circumscribed effects, and their results may greatly contribute to a better understanding of human behavior. However, the applicability of such results to real social contexts calls for their embedding into an appropriate, general theoretical framework [55]. On the other hand, an approach based on the analysis of narratives does not allow to differentially isolate single effects, and is rather geared toward testing the meaningfulness of a compound of effects and hypotheses, again under the roof of a suitable theoretical framework [56]. Both options suffer from substantial limitations and are based upon a complex constellation of assumptions (explicit or not), and are therefore complementary, both as to their shortcomings and potential.

An approach to fiction as the outcome of a process of social learning under evolutionary constraints may be deployed in bio-cultural terms, based upon recent research in evolutionary psychology, and more generally in evolutionary sciences [57]—and even phrased in explicitly Darwinian terms [58]. Besides the by now rich literature devoted to the bio-cultural approach to literary fiction [59], analogous considerations have already been presented for cinematic fiction [60]. The reference to specific adaptive issues makes such approaches not only compatible, but complementary to the body of psycho-evolutionary literature on mating.

However, in what respect fictional narratives might provide a corroboration of the psychological foundations of certain human behaviors [61]? The theme has been the object of a heated debate in literary disciplines. As already remarked, fictional narratives concern characters that have never existed and events that have never happened, but stand as complex mental simulations [62]. Fiction therefore does not describe ‘real’ situations [63], also in the light of the filtering role of the social construction of the interpretive practices through which we access, and give meaning to them [64]. One could thus argue that legitimizing fiction as a social learning platform ultimately amounts to tweaking it via instrumental, parody-like interpretive manipulations [65]. These objections can be countered, however, by noticing that that there is no need that fiction qualifies as a faithful correspondence to real-life situations or interactions to acquire cognitive and pragmatic value [6], and that the knowledge value of fictional narratives does not necessarily call for a functionalist forcing of narrative devices [66]. The essence of the bio-cultural approach lies in underlining how fiction can be read as a response to specific adaptive challenges, which cannot be reduced to the outcome of a social construction process, in that it plays a key, increasingly understood role in the development of domain-specific human cognition [67], both at the individual and social levels [68]. We can specifically consider fiction as a specialized form of social play [69,70], which we could call cognitive play [71]. Fiction can thus be regarded as a laboratory that allows humans to elaborate, already in the early developmental phases [72], and in a systematic way [73], increasingly sophisticated forms of a theory of mind [74], that allow them to reliably reconstruct in due detail the mental states of the other humans they interact with, and to foresee and interpret their behaviors accordingly. The meaningfulness of fiction does not therefore lie in depicting ‘real’ situations but ‘hypothetically realistic’ ones, which not only present imaginary characters, but are legitimately staged in imaginary settings (including ‘impossible worlds’) while preserving their socio-cognitive value. For instance, Jane Austen novels may be consistently interpreted as a systematic exploration of the role of incomplete information as to the true intentions of potential male partners in the context of female strategies of mate selection, in a society where the cost of a wrong mating choice was basically borne by women [75]—an instance of strategic interaction that lends itself to be explicitly analyzed in game theoretic terms [76].

Fictional narratives reflect and shape our approach to the understanding of events [77], and especially of complex chains of events with relevant social consequences [78]. Therefore, humans pay special attention to causal relationships in fiction [79], tend to better remember causally related fictional events than non-causally related ones [80], and attach importance to events in relation to their roles in fictional causal chains [81], and to the richness of their causal ramifications [82]. This explains why giving emphasis to characters, objects or events that do not play a role in the story’s causal unfolding is often stigmatized by audiences as an abuse. The structure of fictional narratives obeys criteria of cognitive parsimony so as to eliminate possible sources of ‘noise’ in the social simulation, and to best preserve the fiction’s adaptive value as a source of useful heuristics [83], and of emotional insights [84]. The role of fiction in the development of empathic capacities in humans is widely documented both historically [85] and experimentally [86]. The selection and attraction of a mating partner provide obvious examples of situations that call for both the understanding and the interpretation of complex sequences of social events, and the skillful emphatic reading of the involved subjects [87]. Therefore, we can consider romantic fictions as laboratories for the representation, comprehension, and interpretation of events deriving from male-female interactions with relevant mating-related implications [12,88]. Fictional social simulations foster a subtly balanced attitude as far as learning is concerned: the cognitive distancing from characters allows a reasoned insight into the implications of their behaviors and choices, while the deep emotional resonance with their vicissitudes marks the latter as subjectively relevant experience [41,89]. It is not surprising therefore that, in the context of the bio-cultural approach, it is possible to single out socially validated fictional narratives that prove useful to the understanding of the micro-structure of the male-female interactions in mating situations, and of their psychological and behavioral foundations, as the result of long, cumulative historical processes of social learning [90].

Creating fictional narratives (romantic or not) with high social cognition value is difficult [91]. In their narrative deployment, there is a concurrence of elements that serve hedonic (pleasure-seeking) and eudaimonic (truth-seeking) motives [92], both of which carry intrinsic value. Fictions that mainly serve a purely hedonic entertainment motive, however, are mainly targeting relaxation and psychological detachment [93], and have modest social cognition value. Social cognition is strongly related to sense-making, and thus to an appreciative attitude that attaches value to complex logical and emotional stimulations [94], and does not eschew sad or problematic themes [95]. Meaningful experiences of appreciation are associated to human virtue dilemmas and to insightful reflection on lifetime goals and purpose [96]. Motivated cognition, driven by emotional motives, plays a key role in determining the cognitive depth of appreciation of exposure to fictional narratives [97]. Emotionally moving narrative contexts are, in turn, more effective in eliciting reflective responses [98], an aspect that is of special importance in the social cognition of mating processes. Not surprisingly, then, romance fictions are more conducive to interpersonal sensitivity than most other literary genres [99]. By stimulating reflection, eudaimonic appreciation improves affective self-regulation and well-being [100], as well as self-perception and acceptance, together with relief for relatively distant affective losses [101]. The effects of eudaimonic appreciation are moreover stable and consistent across different media [102], and are especially significant when a permanent personal commitment toward a certain fictional world (fandom) is established [103]. On the other hand, the stability of hedonic vs. eudaimonic motives across different cultures is more problematic and calls for context-specific analysis [104].

An eudaimonic interest for fictional narratives with sad or tragic implications reveals a willingness to experience emotions (meta-emotions) and to improve self-insight [105]. Entertainment-focused, purely hedonic attitudes toward narrative may on the contrary nurture illusory, stereotypical relational expectations in real life situations [106], thus worsening rather than improving the mind reading and empathic capacities of readers. Only a limited number of fictional narratives is recognized and inter-generationally transmitted as part of a socio-cognitively validated canon, which may markedly differ from the corresponding current academic canon [107]. In general, in the short-term, box office returns tend to reward hedonic fictional narratives more than eudaimonic ones, whereas the latter are met with higher critical acclaim [108]. However, certain eudaimonic narratives receive at the same time both viewers’ and critical acclaim, and leave a permanent impression in audiences due to their meaningfulness and to the richness of the spectrum of mixed affects they can evoke [109]. The value of permanence of such narratives depends upon the fact that their deep structure and the features of their main characters are only in part shaped by the prevailing social conventions and ideological representations of the time (that is, by the factors that play a central role in social constructionist approaches). They maintain their value also beyond their socio-cultural context of reference [110] in that they reflect, as it can be deduced for instance from a selected sample of Shakespearian quotes, fundamental aspects of the human mating dynamics as modeled by long-term sexual selection and by biological and social evolution [111]. By providing a detailed analysis of Shakespeare’s Hamlet from a neuro-scientific perspective, [112] offers an illustration of the level of accuracy of fictional narratives in capturing subtle aspects of the cognitive and affective dimensions of human nature, which have only very recently become intelligible to us in scientific terms. Cognitive models of story comprehension and production, and collected neurophysiological evidence show moreover a significant level of agreement [113], although the relevant neural circuitry is extremely complex and largely still not fully understood [114].

It is well known that language plays a key role in the evolutionary selection of cooperation [115]. Moreover, collective expression activities such as making music or dancing are in turn quite effective in promoting pro-social behaviors, already in early childhood [116,117]. Fictional narratives allow an extra step in making social norms explicit, and in contributing to the solution of common knowledge problems by means of the creation of a common reference among players, as shown by [118]. [119] illustrates how a central theme in fictional narratives is the altruistic implementation of social norms. [120] clarifies the role of literary narrative in the evolutionary development of non-self-centered moral sentiments. In an evolutionary psychology context [121], stories help listeners to refine their understanding of social emotions [122], within a controlled context where it is possible to identify and simulate possible scenarios and event unfolding schemes. They also enable the investigation of one’s own instinctual feelings, impulse reactions and emotional responses to typical social situations which could become highly relevant in future life course [123], or just hypothetically [124]. Through stories, individuals may develop and test those capacities for attention, intelligence and cooperation that are necessary for an effective management of the most complex social interactions [59]. The emphatic and prosocial effect of fiction exposure is moreover potentiated when subjects generate imagery that makes the narrative situation more concrete to them [125]. Personal characteristics, however, imply different consequences of exposure to certain fictional narratives in terms of emphatic understanding and prosocial behavior [126]. As illustrated in the first part [2], the mating dynamics in terms of the Tie-Up Cycle (TU-C) may be regarded as a joint cooperative effort between different-sex players, and therefore the bio-cultural approach turns out especially appropriate as an ‘experimental’ platform for the evaluation of the adequacy and effectiveness of mating behaviors and strategies.

If fictional characters are modelled by evolutionary pressures that reflect basic aspects of human nature in connection to certain social situations [127], their psychological features cannot be interpreted as mere compositional choices by the authors, or as a mere reflection of certain ideological social constructions [128]. They must also reflect some level of understanding of human nature [129], which allows us to interrogate characters in analogy to what we do with living experimental subjects, and to analyze their ‘responses’ by means of suitable psychological tools [130]. [131], for instance, explicitly tests, upon the narrative schemes of a certain number of tales, a social constructivism hypothesis that European popular tales are shaped by a socially modelled ideology of male domination, and shows that the hypothesis receives a modest empirical support. [132] presents a comparative analysis of male characters with a prevailing sexual vs. emotional orientation regarding the mating process, and examine the dilemma, from the female perspective, between the genetic endowment of the dominating, sexually opportunist male vs. the offspring rearing capacity of the sensitive, sexually faithful male [133]. To this purpose, characters from British romance literature are exposed to the evaluation of a sample of women, to verify whether more dominant characters tend to be selected more often by women who are more oriented to short-term mating, and vice versa. The hypothesis is substantially supported by experimental results. Fictional characters seem therefore apt to systematically elicit human behavioral responses and choices that are coherent with our understanding of mating strategies, through suitable role simulation and empathic identification processes [134]. On the other hand, fictional characters are not quite mere narrative depictions of ‘actual’ human beings [135], and need to fulfil specific ‘conditions of existence’ [136]. They are multi-faceted entities [137] that evolve through their dynamic interaction with their audiences [138]. This latter aspect ultimately determines whether a certain fictional narrative is inter-generationally transmitted or not, by being socially validated on the basis of its capacity to spark a significant social diffusion of re-reading/re-narration practices [139]. In our case, the fictional narrative must be validated as a relevant characterization of certain mating-related situations and dynamics, to be legitimately considered both the result of, and a source of inspiration for, social learning processes that transmit useful information on these topics [140]. For this reason, we will focus upon some very well-known cinematic narratives which have been significantly appreciated by audiences worldwide, leaving in turn a traceable mark in the collective imaginary of couple formation processes in the 20th and 21st century, in the USA and globally.

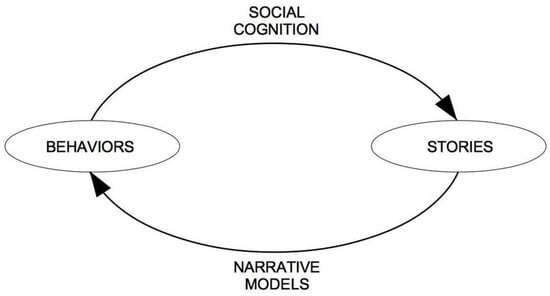

We can sum up some salient aspects of the previous discussion by concluding that the interaction between narratives and behaviors can be characterized as a co-evolutionary process [141]. The dynamic link from behaviors to stories is determined by the adaptive challenges posed by the social cognition of mating processes. The dynamic link from stories to behaviors is driven by the cultural influence effect, in terms of between-partner cooperation (and specifically of shared attention and intentionality in the unfolding of the mating process), facilitated by stories-driven insight into the situations and issues that are typical of the mating sphere of human experience. In other words, the behaviors-stories and stories-behaviors links define, respectively, the ‘exploratory’ and ‘implementation’ phases of the narrative social cognition of mating processes. Such co-evolutionary process is synthetically depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The process of co-evolution between narratives and behaviors.

3. Couple Formation as a Basic Narrative Theme

As already observed, mating situations and issues occupy a particularly important place within the corpus of human narrations [142]. Even when their role in the story is not central, the formation of one or more couples almost always pops up within the narrative arc [143]. And very often the formation of the couple (or of more couples) functions as a basic pillar of the narrative itself. All this attention seems to suggest that, from the social cognition viewpoint, mating issues present an almost inexhaustible richness of possibilities [144], which lend themselves to the development of countless narrative explorations, as well as to the targeted re-interpretation of already familiar ones [145]. However, in which sense should this be truer of mating with respect to other spheres of human experience, of equal relevance from the point of view of evolutionary success, such as for instance the processes of production of goods and accumulation of wealth?

The theme of couple formation is generally associated to that of the development of personality and more generally of human faculties, and to the eventual achievement of the full range of human decision-making and emotional capacities [146]. Consequently, in romances, changes in the personality of characters due to the narrative unfolding of events, tend to be more pronounced than for humans in comparable conditions [147]. The union with one’s ‘other half’ generally stands for a sort of symbolic demarcation of the passage between a developmental phase and the next one, not only in terms of age, but of psychological maturity [148]. This is a result of the overcoming of the obstacles and trials that, along the narrative arc, prevented the characters from accomplishing their union, prompting them to upscale their individual qualities to an extent that, in some cases, is nothing short of a full-blown transformation [11]. In stories with a full eudaimonic valence, the nature of the obstacles to be overcome, moreover, is not merely incidental. It is the substantiation of cognitive conflicts whose relevance and implications extend beyond the characters’ sphere, to ideally address the reader [149]. The eudaimonic valence of the romantic fictional narrative is further reinforced by the arousal of tender affective states that is a natural counterpart of romance [150]. With the formation of the new couple, the partners question their own, original socio-affective environment and together commit to the co-creation of a new relational space, partly self-produced through an effective cooperative combination of reciprocal idealizations [151]. Such mutual adaptation needs to prove its adaptive value, by ensuring the continuity of the process of inter-generational transfer of genetic endowment, material resources, and knowledge [152]. It is no wonder, therefore, that the theme of couple formation takes on such a central place in narratives, also in social contexts characterized by a strong relativism as to the existential meaning of romantic love [153]. The possible formation of a stable couple is directly linked not only to the adaptive survival of the human kind, but also of the stories themselves through their inter-generational transmission [154]. Not incidentally, in the most elementary forms of narration such as in many tales of popular tradition (which often serve as matrices for up-to-date narrative re-modulations; see e.g., [155]), the formation of the couple is not only the point of arrival of the narrative but also its definitive fixation. Once the couple is successfully formed, there is no more urge to go on with the story, as everybody will “live happily ever after”—despite the ‘after’ notoriously being the most critical phase, and a most interesting source of narrative complexity [156].

Equally important themes, such as the already mentioned one of goods production and wealth accumulation, find a much more problematic collocation within the narrative repertoire, and the main reason is the ambiguity of their relationship with the afore-mentioned process of maturation and achievement of the human developmental process [157]. Within the economy of the narration, the formation of a couple has always a positive valence, insofar as the partners begin a relationship founded on deep affinities, and thus stable and psychologically (and often biologically) rewarding [158]. The fact of finding a ‘soulmate’ and getting united is the object of a univocally positive evaluation in the perspective of the narration, even when such union may be jeopardized by unsurmountable difficulties or by tragic combinations of circumstances that prevent it from fully happening, for instance because of the death of one or both partners [159]. In other words, the formation of the couple, if happening appropriately, always yields a positive impact in terms of a full realization of the human potential of the characters, and acquires a possible exemplary value [160]. On the contrary, the formation of a couple with the ‘wrong’ partner inevitably yields tragic, and possibly irrevocable consequences [161]. A successful mating, therefore, provides an example of moral clarity that elicits cooperation in viewers [162], and, if marked by dramatic circumstances, even feelings of elevation [163], which explains in turn its centrality in human fictional narratives.

The main message that the narrative repertoire seems to transmit from the viewpoint of the social cognition of mating is the importance of choosing the right partner [164], and the simultaneous necessity of making the couple ‘safe’, by stabilizing it through a process of personal, reciprocally orientated growth of both partners, and of knowledgeable conflict resolution [165], to make the mating resilient with respect to a vast array of external circumstances that might threaten it.

In the case of other evolutionarily relevant themes such as goods production and wealth accumulation, there is not, within the body of the narrative repertoire, an equally unanimous evaluation in terms of a positive association between the achievement of the goal and the full deployment of human potential [166]. Even when, for instance, wealth is accumulated effectively and at the same time honestly, there is always the risk that the achievement of abundance may corrupt the character, exposing him/her to various tragic developments [167]—and this is of course true a fortiori when wealth is achieved through unlawful, or morally dubious choices [168]. In other words, there are human activities whose evolutionary benefits are undeniable, such as wealth accumulation, but whose evaluation in terms of narrative social cognition turns out to be ambiguous, because of their possible negative effects on personality development and moral prowess [169]. Whereas morally ambiguous characters may actually fulfil hedonic entertainment motives through the mediation of moral disengagement [170], morally clear ones prompt appreciation through the mediation of self-expansion [171]. The centrality of the mating process within human narrations therefore represents the implicit recognition of its value as a foundational element of human development, with respect to which it assumes an almost paradigmatic role [172]. Other dimensions of human experience, equally important in principle in their evolutionary implications, occupy a less central position and are subject to a more nuanced evaluation because of their susceptibility with respect to certain aspects of human nature that present widely recognized criticalities, such as the effect of an excessive abundance of material resources [173].

The implicit thesis that underlies the centrality of the mating process in fictional romantic narratives, according to which the formation of an ‘appropriate’ couple always yields beneficial effects for the involved subjects, as well as for the community in the light of what we know of human nature [174], is openly questioned by the schools of thought that regard the typical deployment of romance narratives as a sneaky celebration of the female enslavement to the norms of a patriarchal society [175]. However, considering by default romantic fictional narratives as mere expressions of an ideology of gender dominance amounts in practice to a petition of principle, which does not give to such narratives a fair chance to prove their socio-cognitive value [176]—an aspect which cannot in turn be taken for granted, but must be demonstrated with respect to specific adaptive issues.

4. Tie-Up Theory: Basic Notions and Implications for the Fictional Social Cognition of Mating

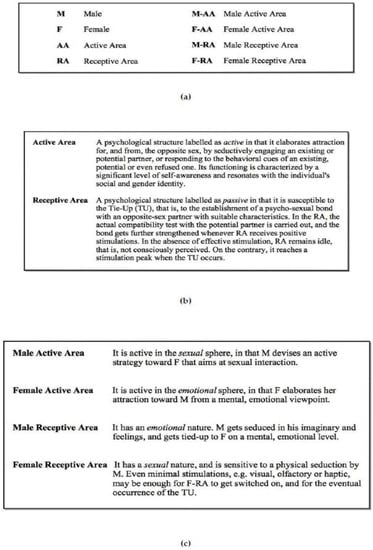

In this section, we review the basic concepts of the Tie-Up theory presented in [2], which are useful for our analysis of the socio-cognitive dimension of mating in fictional romantic narratives. We report the theory’s basic notation and definitions in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 for the reader’s convenience.

Figure 2.

(a) Basic terminology; (b) Active and Receptive Areas; (c) Characteristics of Male vs. Female Active and Receptive Areas.

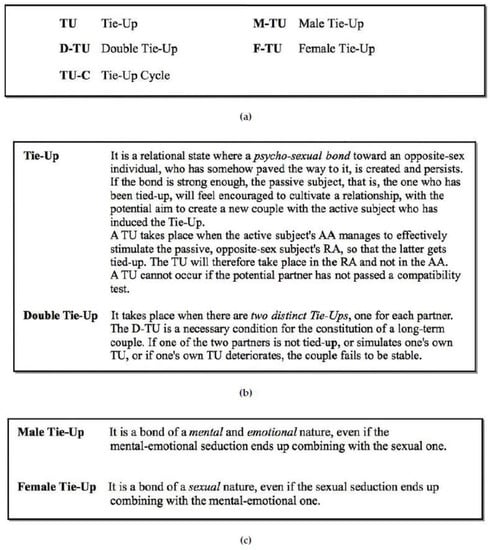

Figure 3.

(a) Basic Tie-Up terminology; (b) Tie-Up and Double Tie-Up; (c) Male vs. Female Tie-Up.

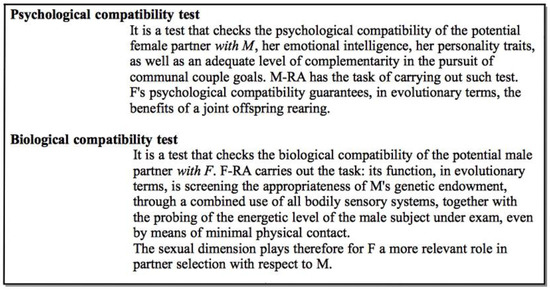

Figure 4.

Compatibility tests.

Figure 5.

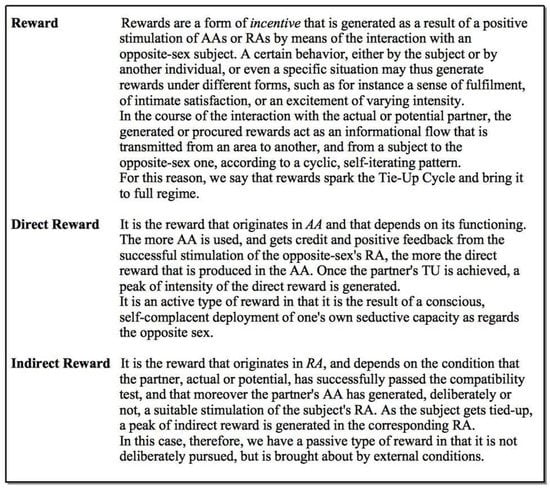

Rewards.

Figure 6.

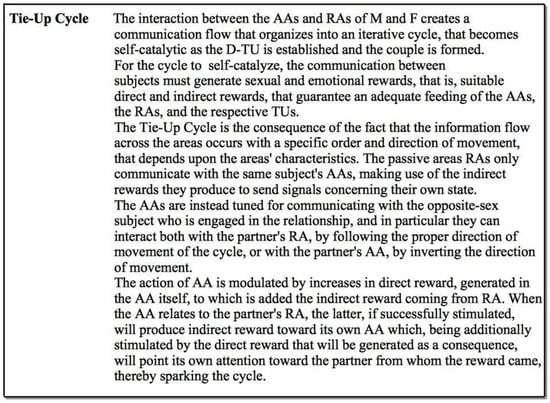

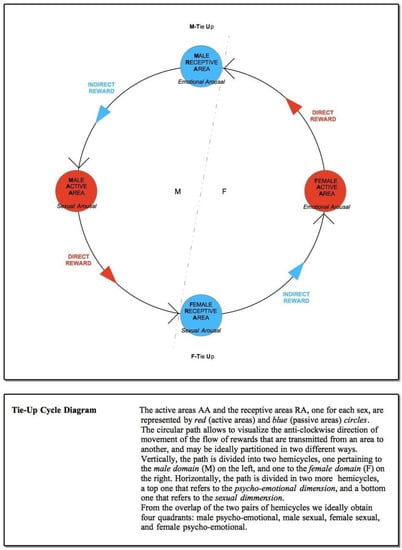

Tie-Up Cycle.

Figure 7.

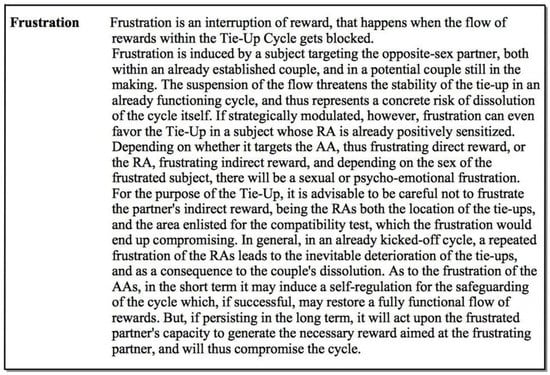

Frustration.

Figure 8.

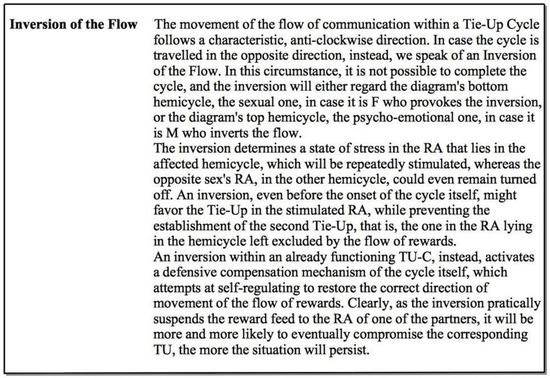

Inversion of the flow.

Figure 9.

Tie-Up Cycle Diagram.

Reframing the previous discussion on the fictional social cognition of mating in terms of the Tie-Up theory’s conceptual framework is quite natural.

In the perspective of narrative social cognition, the union with one’s ‘other half’ acquires an almost normative value as a metonymic representation of the full achievement of human potential, both individually and collectively, with a strong valence of compensatory idealization of the dysfunctionality of real couples [177]. The formation of a couple with the appropriate partner brings with it an expectation of existential fulfilment with positive collective spillovers [178]. Thus, the effective completion of a Tie-Up Cycle (TU-C) [2], and the consequent emergence of a stable couple elicits social recognition as an indirect result [179]. The interruption of a TU-C and the ensuing dissolution of the couple, on the contrary, prompts a perception of damage, not only at the individual level, but at the social one as well. The responsibility of the break-up must be traced back, depending on cases, to one of the partners or to both, as an effect of an evaluative deliberation that any subject outside the couple feels entitled to carry out, consciously or unconsciously, on the basis on his/her own knowledge of the relevant facts and of his/her social and emotional closeness to either partner [180]. As already pointed out above, the cooperation among partners within the couple tends to be regarded as a public good, and therefore the couple break-up creates a social incident [181], with the consequent, spontaneous activation of social defense mechanisms such as gossiping, which at least in part function as a deterrent [182].

In the context of the Tie-Up theory (TU), the iteration of TU-C may be regarded as nothing but the representation of the partners’ human maturation in its various components. When the Double Tie-Up (D-TU) is realized, the male partner M gets a deep emotional reward that does not conflict with, and on the contrary provides a confirmation to, his sexual identity, whereas the female partner F in turn obtains a strong sexual reward which does not threaten, but on the contrary reinforces, her emotional identity. Both M and F thus get, from the couple relationship, a wealth of psychological resources, that are expendable not only within the couple itself, but also in the broader sphere of their social life. And in fact, the empirical evidence shows how a high quality of couple relationship is associated to better results in the various dimensions of social and professional life [183].

On the other hand, as we know from the analysis presented in [2], it cannot be taken for granted that the emergence of a TU necessarily implies positive consequences in terms of individual psycho-social development. If TU is one-sided, it is quite possible that very negative psycho-social developmental effects result. The conditions for the emergence of M-TU or F-TU, as discussed in [2], are essentially linked to the success in carrying out a physical test in the case of F, and a psycho-emotional test in the case of M. The logic of selection that drives such tests is aimed at checking the level of compatibility regarding, respectively, reproductive success and future offspring rearing. However, there is no certainty that the partner to whom one is tied-up will have all the necessary qualities to ensure the formation of a stable long-term couple—an outcome that, as discussed, depends upon a complex dynamic process of reciprocal behavioral tuning. For these reasons, in the repertoire of fictional narratives the relational struggles of unhappy couples command a level of attention comparable to the one paid to the vicissitudes of happy couples, in that, in a problem-solving perspective, issues related to the failure or deterioration of TU deserve a special interest [184].

The theme of the narrative social cognition of mating is generally the object of a particular interest for audiences of female rather than male readers [185]. This difference finds an explanation in the context of the TU theory. As seen in [2], the dynamics of TU-C implies that F is more exposed than M to the risk of a partner’s failed TU and of the ensuing consequences, and especially so if the interaction has led F to sexually conceding to a not yet tied-up M. Therefore, for F more than for M, it is crucial to elaborate a reliable theory of mind that allows her to anticipate and to interpret M’s signals, thereby avoiding exposure to the risk of sexual opportunism from M’s side. Moreover, for F the emotional dimension is characteristic of the Active Area (F-AA), and thus refers to the conscious level of her strategic interaction with M. Then, all the useful elements that are socially transmitted in narrative mode and that may contribute to a deeper understanding of the emotional interaction with M will be of special relevance for F. For M, instead, the emotional dimension characterizes the Receptive Area (M-RA), and is thus essentially unconscious. Consequently, M will be less interested toward, and will associate a smaller strategic value to, the acquisition of narratively transmitted knowledge centered upon the emotional introspection which is the key focus of a large share of the fictional accounts of couple formation. M will attribute more relevance to the social cognition of aspects that are characteristic of the expression of his M-AA, and thus in particular to the strategies of sexual conquest, and to the acquisition of resources that improve the effectiveness of such strategies (material wealth, power, physical prowess). Men’s preferential attention will therefore be directed toward narratives centered upon relatively more hedonic topics of competition, conflict and antagonistic achievement of real or symbolic goals [186].

5. The 6 Ways and Their Interaction Diagrams

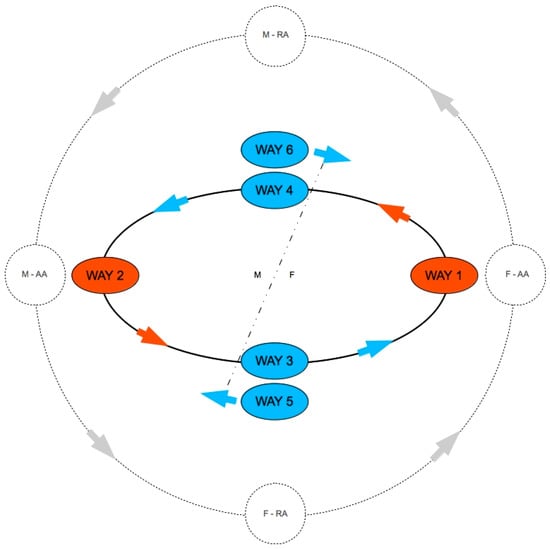

In [2] the notion of Way has been introduced as the initial path that marks the start of a TU-C. Such early phase has a key role in the further dynamic development of TU-C itself. Depending on who, between the two potential partners, takes the initiative, and on the area from which the interaction starts, it is possible to single out six basic cases, three for each sex. The summing up diagram, that helps to associate the Ways’ numeration to the various cases (see Figure 10), visually synthetizes the relationships between each Way and the AA vs. RA of M vs. F from which TU-C takes off. Specifically, TU-C starts from AAs are depicted in red and starts from RA in blue for each hemicycle, male and female. It turns out, then, that to each AA corresponds only one possible Way (1–2), whereas from each RA two different Ways can depart (3–5 vs. 4–6), depending on the direction of movement of TU-C—clockwise or anti-clockwise.

Figure 10.

The six Ways and their relationships with the positions in Tie-Up Cycle (TU-C).

Red arrows indicate the direction of movement of the cycle in Ways 1–2, which, departing from the respective AAs, will head toward the RA of the opposite sex’s partner along the only possible path, by following the same direction of the grey arrows that indicate the natural anti-clockwise movement along TU-C. The blue arrows, instead, may move both anti-clockwise—as in Ways 3–4—or clockwise—as in Ways 5–6. Ways 5–6, in particular, represent the cases of inversion of the flow, where after the departure from the RA, once reached the AA within one’s own hemicycle, the subject’s AA does not choose to go on toward the partner’s RA, but turns back and directly communicates with the partner’s AA, so as to induce the partner to increase the stimulation of the subject’s RA. Way 5 and Way 6 lie outside the central ellipse to indicate their higher criticality, as we shall see, from the point of view of an effective start of TU-C, due to the additional difficulties posed by the fact that, in these two Ways, one moves in the opposite direction with respect to the TU-C flow.

To sum up, the Ways characterized by female initiative have odd numbers (1-3-5), whereas those characterized by male initiative have even numbers (2-4-6). The Ways in red that depart from AAs, that is from the active areas of each sex, represent the classical approach to the other sex: The relational one for women, who approach men by establishing a psychological and emotional tuning (Way 1), and the sexual one for men toward the woman who physically attracts them (Way 2). The Ways in blue that depart from the RAs, that is from the passive areas of each sex, which as we know regulate the TU, present two different possibilities of approach, depending on whether one moves across the ‘long’ or the ‘short’ path. A woman who feels physical attraction for a man and decides to seduce him has therefore two options, that correspond to two different types of seduction. In the case of Way 3, we will speak of a mental type of seduction, more sensual than sexual, by F who aims at conquering the M-RA of the man toward which she feels physical attraction. In the case of Way 5, instead, the seduction will be explicitly and directly sexual. For a man who experiences a psychological fascination and curiosity for a woman, toward whom he will also grow a physical attraction and interest, there will be again two approach options. The first is physically seducing the woman with a targeted sexual approach (Way 4). The second is inverting the flow and addressing her as a friend and confidant, who understands and supports her, with a relational approach aiming at the creation of an affinity connection rather than of a sexual one (Way 6).

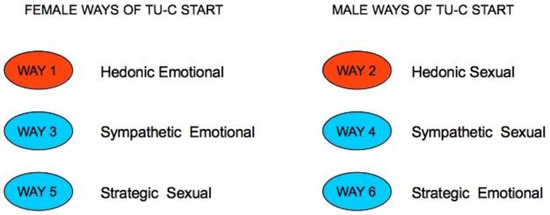

In short, Ways 1–2, by moving from the respective AAs of F and M, leverage upon the subject’s own direct reward and are thus characterized by a hedonic approach, focused upon the own pleasure of the subject who takes the initiative and that is centered, in the case of the woman, upon the emotional sphere, and in the case of the man, upon the sexual one. In Ways 3 and 4, the start is from the activated RAs and addresses the opposite sex partner’s RA, thus aiming at a double activation which literally assumes a sympathetic character. In Ways 5 and 6, finally, the start still occurs from the activated RAs, but now addresses the opposite sex partner’s AA, to obtain a response that ensures an interest from the latter, which is being directly rewarded, so that it persists in the interaction. We will therefore speak in this case of a strategic approach, in that the purpose of the subject who takes the initiative is that of binding the partner, while at the same time avoiding the test and the consequent risk of failing it. Figure 11 illustrates the scheme just presented. Between the hedonic Ways 1–2, Way 1 is characterized emotionally and Way 2 sexually. Between the sympathetic Ways 3–4, Way 3 is once more emotional whereas Way is still sexual. Finally, between the strategic Ways 5–6, Way 5 is sexual and Way 6 emotional.

Figure 11.

The driving elements in the 6 Ways, and the initiative lead by male (M) vs. female (F).

The difference between the starts from AAs and those from RAs is their implications in terms of the rewards that are produced. Starting the cycle from one of the AAs implies starting with a production of direct reward in the hemicycle of departure, in the absence of an additional indirect reward and with the RA in the same hemicycle still turned off. The activation of the latter will exclusively depend upon the behavior of the potential partner—and in particular upon the extent to which the partner will be willing to travel along his/her own half of the cycle. Starting from a RA implies instead the production of both rewards, direct and indirect, and this exposes to the risk of a TU before the partner gets tied-up in turn. In this case, therefore, choosing the ‘long’ path (Ways 3 and 4) means caring in the first place about the fact that the partner gets tied-up, even before stimulating the potential partner’s AA (‘short’ path), to amplify the production of indirect reward by the subject’s own RA (Ways 5 and 6). Ways 3 and 4 represent the ‘long’ paths because, in the case of the woman, she intends to stimulate M-RA to arrive to M-AA only afterwards, that is, to the sexual sphere that will produce the additional indirect reward she is craving, thus determining or reinforcing her own TU. Likewise, the man will target F-RA before moving forward to F-AA, which will eventually boost his indirect reward of an emotional nature, thus determining or reinforcing the male TU. The bigger risk that is implicit in this conduct is the possibility of a negative outcome of the compatibility test by the opposite-sex potential partner, which would jeopardize any possibility of a TU. On the other hand, if the test is passed successfully, there will be a concrete possibility that TU-C will be entirely travelled along several times, and that the D-TU that is necessary to its maintenance will consequently shape up. In the case of Ways 5 and 6, the short path leads, independently of any compatibility, to an immediate increase of one’s own indirect reward (sexual for the woman, psychological-emotional for the man), while at the same time substantially reducing the possibility of activation of the potential partner’s RA, and thus making it more difficult that the latter gets tied-up and that the TU-C actually starts.

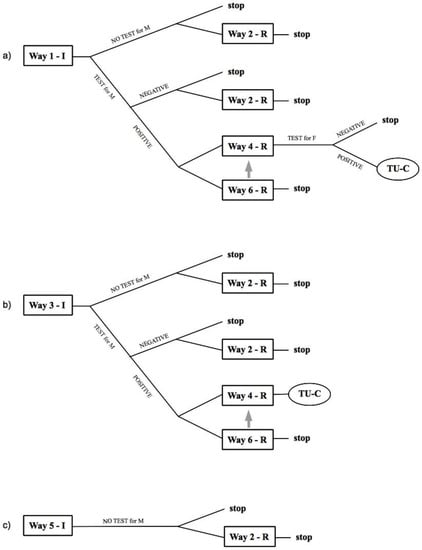

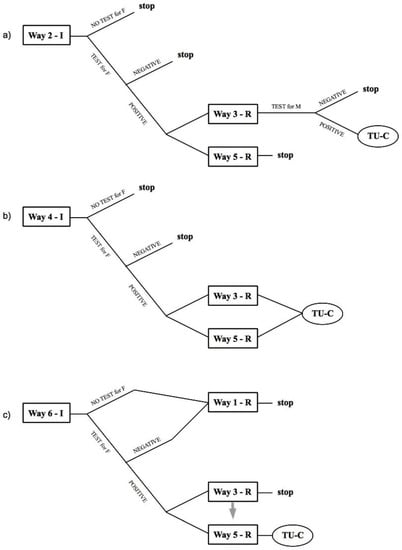

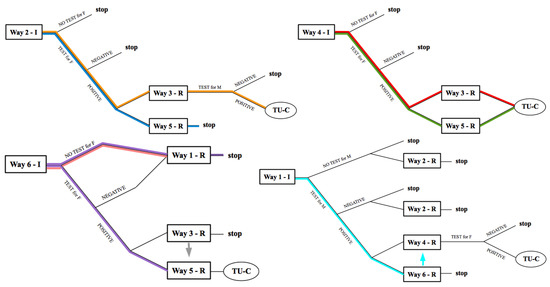

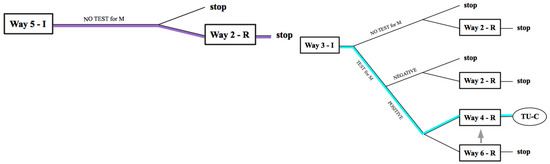

The complexity of the initial interaction dynamics in the launch of a TU-C cannot obviously be reduced to the Way chosen by the initiator subject who enters the cycle first. The start of a TU-C by one of the potential partners inevitably implies a response by the opposite-sex subject—in case s/he has an interest in being involved—who will in turn enter TU-C from an own, characteristic Way. We can thus identify two types of Ways: the one of the initiator, that we will call the Impulse Way (Way-I), and that of the potential partner who reacts consequently, that will be called the Response Way (Way-R). We obtain accordingly the interaction diagrams shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Interaction diagrams with an impulse by F. (a) F’s entry in TU-C from Way 1; (b) F’s entry from Way 3; (c) F’s entry from Way 5.

Figure 13.

Interaction diagrams with an impulse by M. (a) M’s entry in TU-C from Way 2; (b) M’s entry from Way 4; (c) M’s entry from Way 6.

From the viewpoint of the launch of TU-C, and thus of the possible creation of a long-term couple, Way-I represents only the first step of a dynamic interaction that can be depicted in terms of a tree diagram, and in fact it is the choice of Way-R that determines, to a large extent, the success or failure in terms of TU-C completion vs. breakdown. The presence of several points of arrest of the cycle, indicated with “Stop” in the diagrams, shows how the possibility to get into a dead end is more likely than it could be expected. For a woman who takes the initiative, the formation of a stable couple with the chosen partner only occurs in one and a half cases (that is, one case plus a further, specific sub-case), a much narrower range of opportunity if compared to the three and a half favorable cases that can occur if the initiative is taken by the man.

Let us now examine in detail how the interaction may unfold when it is F who enters TU-C first, from one of the positions Way 1-3-5 schematically represented in Figure 12. A F who starts from the position Way 1-I is in a situation of excitement of her own F-AA. She has found a M toward whom she feels an emotional attraction, in terms of admiration or appreciation of some personal characteristics such as personality traits (kindness, amiability, moral integrity etc.), talents (intellectual brightness, creativity, professional skills etc.), resourcefulness (wealth, power, etc.). Even the fact that the man is the object of special attention by other women, who are considered a valid benchmark in some capacity, may in some cases spark interest. These factors, if attractive enough for F, may fuel an emotional excitement which, irrespectively of the physical traits or looks of M, will provide a level of direct reward for F large enough to prompt her to activate her F-AA toward M, to amplify such reward as much as possible. When F-AA addresses M-RA on a psycho-emotional level, following the natural direction of movement along TU-C, it will likely end up activating the psychological compatibility test by M, which as we know is generally unconscious and automatic. However, such test could also fail to be launched if M quickly leans toward a sexual appreciation of F, intentionally disregarding the emotional level, and thwarting the very possibility of a psychologically-driven interaction. If M does not carry out the test, there are two possibilities. Either M refuses the Way 1 approach by F and does not enter the TU-C at all, so that the latter aborts even before the start (Stop), or he enters TU-C from a Way 2-R position, engaging F on a sexual level of interaction. Also in the second case, in the best hypothesis that F successfully carries out her biological compatibility test on M and consequently activates her F-RA, thereby accepting M’s sexual approach, the breakdown of TU-C is only a matter of time, and will depend on the speed of decay of the peak of direct reward enjoyed by M. If instead M starts and completes his test of psychological compatibility on F, there are again two possible outcomes. If the test is negative, as above, M will not enter TU-C or will enter it from a Way 2 position. If conversely the test is successful, M will feel a psychological and emotional attraction for F. This is the only path that opens a possibility of a solid launch of TU-C, provided that M enters the cycle through an appropriate Way.

AA and RA, as already remarked, correspond to two different relational dimensions for each sex: The sexual, and psycho-emotional ones. The initiator of the TU-C, depending on the chosen Way-I, implicitly opts for one of them. For an appropriate deployment of TU-C, each dimension may accommodate only one TU, that is, the one of the initiator or that of the respondent. Ruling out the cases where the initiator acts upon a different dimension than the one onto which s/he previously tied-up (that is, the cases Way 4-I and Way 3-I), to have a stable TU-C it is necessary that, whatever the dimension that corresponds to the chosen Way-I, Way-R responds onto the opposite one, to pave the way for the second TU, which is indispensable to the launch of TU-C. If therefore Way-R remains on the same dimension as Way-I as in the case of Figure 12a, where Way 6-R responds to Way 1-I, the only possible unfolding will be a Stop. If indeed F moves from Way 1-I, acting on the psycho-emotional dimension with a non-activated F-RA, the only effective response for M, to keep a concrete possibility of TU-C open, is that of tying-up himself first onto the same dimension of Way 1-I, to subsequently provoke the Tie-Up of F by switching to the opposite dimension, that is via a sexual approach from the position Way 4-R. In the case of Way 2-R, we likewise have a switch to the opposite dimension, as M moves to the sexual dimension to which F is sensitive, thereby creating the conditions for F to tie-up, but in the absence of M-TU. If instead M, as the consequence of a successful psychological compatibility test favored by Way 1-I, gets tied-up and enters from the position Way 6-R without moving to the opposite dimension, he will remain the only one to be tied-up, that is, will experience a one-sided attraction, whereas F will feel perfectly fulfilled by the intense friendship relationship with M. On the other hand, in the position Way 6-R, M has already gone a long way down the approaching path to F, and thus, in this condition, he could venture into a change of Way, shifting from Way 6-R to Way 4-R (as indicated by the grey arrow in Figure 12a), with the consequent, necessary change of dimension of interaction.

When, to the contrary, F enters TU-C on a sexual dimension, this is the case of Way 5-I (see Figure 12c). In the absence of manipulative intentions by F (a case that we rule out here), her F-RA will be activated, and possibly F-TU could have occurred already. Now, M has simply to choose between two possibilities—accepting the sexual offers of F, or not. This kind of entrance into TU-C by F does not induce any compatibility test by M, and does not reach out to his M-RA. If M responds, he will do it onto the same dimension with Way 2-R, without shifting to the psycho-emotional dimension, not having previously matured an interest toward F yet. Consequently, there will be no possibility of completing the cycle, and TU-C will break down before the start. In the Way 2 position, M has no incentive to shift to the opposite dimension, and likewise for F in the position Way 1, for the simple reason that their RAs have not been previously activated, and therefore they have no drive to go for an indirect reward, being already fully gratified by the direct rewards generated by their AAs. In such situations, TU is precluded.

In other words, for TU-C to take place, Way-R may respond on the same dimension of Way-I only if the initiator subject is already tied-up on the opposite dimension. If this is not the case, for TU-C to be launched, the respondent subject must switch to the opposite dimension with respect to the one that is characteristic of Way-I. For this reason, the role of the respondent is crucial, in that s/he has an opportunity to correct any TU-C setup errors by the initiator. The subject that initiates by moving from a Way-I that is relatively unfavorable to the launch of TU-C, for instance F in a position Way 1-I, will call for a very precise response by M, namely, in our example, Way 4-R—an effective seduction of F in the context of a pre-existing male, emotional Tie-Up. Any other response by M would jeopardize the possibility of a D-TU.

In the case of an entry by F in a position Way 1-I, instead, it’s she who now has a turned off F-RA, but acting on a psycho-emotional dimension with the consequent stimulation of M-RA, she can induce the test by M. The same happens for position Way 3-I, with the difference that in this case F has already carried out with success her test on M, so that, if also M’s test on F succeeds (and in the absence of external obstacles, that we do not consider here), TU-C will be safely launched with no need for further preliminary moves. Both in the case of Way 1-I and Way 3-I, it will be necessary that M switched to the opposite dimension, moving from the emotional to the sexual one, and this may happen directly by entering from Way 4-R or, if the initial response is from Way 6-R, by subsequently moving to Way 4-R, as indicated by the grey arrow. Remaining in Way 6-R would preclude the launch of TU-C.

When it is M who takes the initiative, his approach will be sexual in two cases out of three (see Figure 13). In fact, positions Way 2-I and Way 4-I are very similar and may be a source of confusion, if not for the fundamental difference that, in Way 2-I, M-RA is not activated, whereas in Way 4-I it is. In Way 4-I, M has already chosen his partner, and is proposing to her to launch the TU-C (Figure 13b). In this case, if the biological compatibility test is successful (and there are no external obstacles), M now faces a safely successful path, independently of the Way-R from which F enters the TU-C. For M in Way 2-R, however, the goal is not the launch of TU-C, but there is a possibility that F, from a Way 3-R position, manages to induce M’s psychological compatibility test and to activate his M-RA. If this is the case, the TU-C will be launched even starting from a Way 2-I position. That is, M will be unintentionally but successfully involved on the psycho-emotional dimension because F has skillfully managed to switch the dimension of interaction on which Way 2-I took the lead. If on the contrary M does not approach F sexually, and enters from Way 6-I (see Figure 13c)—for whatever reason, and not necessarily due to M’s lack of confidence as to the sexual prowess of his M-AA—and so, if M keeps himself clear of a close physical reach by F, maintaining a normal level of relational distance, he will not create favorable conditions for F’s biological compatibility test. F will then simply feel gratified by M’s attentions, and will appreciate the pleasure of interacting with M on a psycho-emotional dimension, only enjoying a direct reward, whereas her F-RA will remain turned off, and any possibility of a TU-C will be ruled out, even if M-TU has already occurred.

M could enter the TU-C from a Way 6-I position because his RA has been stimulated by a woman toward whom he is developing a psycho-emotional interest of some sort, and this position allows an approach to F that does not entail the risk of an immediate Stop. Such a risk would be incurred instead by moving from Way 2-I or Way 4-I. The Way 6-I move thus enables M to safely carry out his test of psychological compatibility on F, taking all the time needed. However, if M is already tied-up or gets tied-up meanwhile, and persists in Way 6-I because he feels insecure, he will have no chance to arrive at TU-C unless it is F that shifts the relationship to the opposite dimension and thus takes the sexual lead herself, responding from Way 5-R. This situation, however, requires in turn that the biological compatibility test by F has been already carried out independently of M’s initiative and that, in the case of success, F does not enter TU-C from Way 3-R without shifting to the opposite dimension, that is, with F still waiting for M to make the first move in sexual terms. If, in this circumstance, F does nevertheless enter from a Way 3-R position waiting for M’s move, in fact, this means that she is selecting a M with clear masculine characteristics, and will tend to exclude those potential partners who lack a strong enough capacity of initiative.

The cases of flow inversion, Way 5-I and Way 6-I present, in terms of the interaction diagrams, a disparity of possibilities that sees F at a disadvantage with respect to M in taking the initiative to launch the TU-C—the diagram in Figure 12c is the only one without any branches leading to a TU-C. This asymmetry is explained as follows. In the diagram of Way 5-I, there is no chance for M to carry out the test of psychological compatibility on F, whereas in the diagram of Way 6-I the possibility for F to carry out the biological compatibility test on M is contemplated (compare Figure 12c and Figure 13c). The key feature that differentiates the two cases, that should apparently be totally analogous for the two sexes, is the role of the sexual intercourse, which is contemplated in the Way 5-I case, but not in the Way 6-I one—at least until the respondent partner carries out her test as well. The sexual intercourse precludes the psychological compatibility test for the man, in that he, once reached the peak level of his direct reward, will have no incentive to carry out such test, and will rather seek new sources of direct reward. The psychological nature of the male compatibility test and the physical nature of the sexual intercourse may thus cause an experimentation tradeoff for M, which might prevent M’s test on F from happening. Specifically, if M reaches the peak level of direct reward through the intercourse before being induced to carry out the psychological test, his strongly stimulated M-AA will reinforce his propensity to look for further direct (and thus physical) rewards, rather than shifting the exploration to a psychological level in search of indirect rewards associated to the currently unstimulated M-RA, and the test will not take place. On the contrary, for F the physical nature of both the biological compatibility test and the sexual intercourse implies that the latter inevitably paves the way to the former, had the test not previously been completed already.

6. Fictional Narratives as a Social Cognition Laboratory of Mating: Hollywood Romances

The interaction schemes described in the previous section are to be considered as a basic classification of the possible impulse-response configurations between partners, as generated by the functioning of the AAs and RAs in the absence of major interfering factors of external (circumstances, obstacles etc.) or internal (ulterior motives, manipulation, deceit, etc.) nature. In a realistic interaction context, certain external forces might restrict, and in the limit even force or tweak, a certain behavioral response in a certain situation. For instance, there could be misunderstandings as to the identity of the subject of a compatibility test, or motivational problems with the acceptance of its outcome, and so on. Or it could be that the subjects themselves are prompted by a more complex intentionality, such as purposeful manipulation, which would make the interpretation of the signals by the potential partner particularly difficult. This could lead a subject to perceive as real a Tie-Up situation that is in fact only simulated—just to exemplify one of the most common occurrences. The possible variants and complications that may emerge through the action of any kind of internal or external factors are practically countless, and it is for this reason that fictional narratives can be regarded as an inexhaustible pool of social cognition resources for mating-related issues. An interesting narrative will not limit itself to a mechanical reproduction of the schematic unfolding of a certain interaction dynamic. It will explore the consequences of all kinds of external and internal perturbation factors on the eventual outcomes, as implicitly compared with the ideal ones that would emerge in the absence of disturbances. The more such variants will be able to draw attention upon relevant, and at the same time scarcely explored situations, the higher their knowledge value, and thus the interest they can command. On the contrary, an entirely foreseeable unfolding of a certain narrative situation will only be rewarding from the point of view of the momentary confirmation of the audience’s preexisting knowledge and expectations. Its limited socio-cognitive value added, however, will likely cause a quick fading of the audience’s interest through time.

In this section, we will analyze some examples of Hollywood narratives focused on an eudaimonical treatment of the dynamics of couple formation. The chosen movies all belong to the small league of universally renowned and celebrated cinematic romances, one for almost each decade from WWII onwards. All these movies have maintained their interest and meaningfulness for contemporary audiences, so that each of them can be safely said to occupy a distinctive place in the cinematic collective imaginary of our time. Therefore, despite any choice of a small number of movies may inevitably sound arbitrary to some extent, our pick can be taken as representative of the ‘narrative benchmark’ of the Hollywood romance repertoire, as it has been shaped up by audience response and inter-generational transmission in the past few decades. Further analysis on more case studies is obviously called for, but the present sample may be considered as a legitimate point of departure. Each of the chosen movie narratives will be analyzed by means of our theoretical framework. Specifically, we will reconstruct in some detail the main insights on the social cognition of mating that are contained in the narrative unfolding of each chosen movie, and will discuss to what extent such insights can be rationalized in terms of the implications of our theoretical framework.

We will show how, on the one hand, the fundamental structure of all the chosen movies is always traceable back to one of the interaction schemes presented in Figure 12 and Figure 13, and on the other hand how, in each case, the story’s unfolding yields some surprising developments or twists, which are however still interpretable as specific variations of a certain reference interaction scheme. To be appreciated in its cognitive valence, a fictional narrative must offer a reasonable perspective on the deep reasons that pull the potential partners to choose, in given circumstances, a certain mode of interaction rather than another. At the same time, though, the story must also account for the meaningfulness of the internal and external ‘perturbations’ that are introduced in the specific interaction scheme at play, avoiding to call upon artificial or implausible solutions that undermine the socio-cognitive value of the narrated situations. In this regard, we can consider the chosen Hollywood movies as socially validated sources of collective, narrative-based learning on mating-related issues. Their vast, durable social appreciation is the recognition of an effective co-evolutionary tuning between certain narrative situations, which have struck a chord of the collective imaginary and have thus been crystallized as timeless cinematic topoi, and a deep structural layer of actual mating behaviors. This qualifies these ‘movie classics’ at the same time as narrative models of strategic wisdom on real life mating situations, and as encyclopedic repertoires, narrative condensations of the social rumination of countless real life experiences across the generations.

6.1. Gone with the Wind

Among the Hollywood romances selected for our analysis, we start from the less recent one, Gone with the wind (1939). This movie has stably maintained in time a capacity to attract and fascinate several generations of viewers, with its description of a troubled, wavering couple relationship, which offers a wealth of cues to understand the complexity of the factors that enable the formation of a couple, that prevent its creation, and cause its dissolution. That between Scarlett O’Hara and Rhett Butler is thus probably one of the most globally renowned romances which, however, conceals an example of a D-TU that does not lead to the proper formation of a long-term couple. The major cause of a TU-C failure is ordinarily the existence of only one (unilateral) TU instead of two, that is, the fact that one of the potential partners is not tied-up. In this movie, however, despite that both characters get tied-up to the other at some point, so that a D-TU is realized in the couple, TU-C fails nevertheless. The specific problem that emerges in the relationship between Rhett and Scarlett is that their TUs are badly synchronized.

To understand better, let us start from a classification of the characters in terms of our interaction schemes. Rhett—the partner who gets tied-up from the beginning, already at the first meeting—provides a typical illustration of a M that enters first into the TU-C from a Way 4-I position. The fact that he is a consummated playboy should not lead into thinking of a case of Way 2-I, because Rhett represents the man who chooses his female partner under the impulse of his RA, and not of his AA. Even in the case of his habitual lover, the maitresse of the local brothel, it is clear how Rhett’s attraction is based upon a mental rather than physical predilection, which is driven by a sense of affinity and by a psychological correspondence. Scarlett is beautiful, but what intrigues the shrewd tombeur-de-femmes is not just her looks, but rather her capricious vitality, her bold and somewhat childish obstinacy, her coquettish but persistent astuteness that she intentionally cultivates to manipulatively secure the objects of her desires to herself only.