From Laggard to Leader: A Novel Policy Perspective of Michigan’s Preliminary Path to Climate Success

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Michigan Healthy Climate Plan and American Environmental Justice

1.2. Sustainability, the U.S. Federal Government, and the Michigan Health Climate Plan

1.3. Michigan’s Environmental Legacy and a Legislative Push for Change

2. The Path to a Perspective

3. Transformative and Innovative Policy

4. The Michigan Healthy Climate Plan

4.1. Seven Primary Objectives of the Michigan Healthy Climate Plan

4.2. Solar Energy Facilities Taxation Act

4.3. Property Assessed Clean Energy Act

4.4. Clean Energy and Jobs Act and the Clean Energy Future Package

4.5. Policy Matrix for Michigan Healthy Climate Plan Goals

5. From Laggard to Leader?

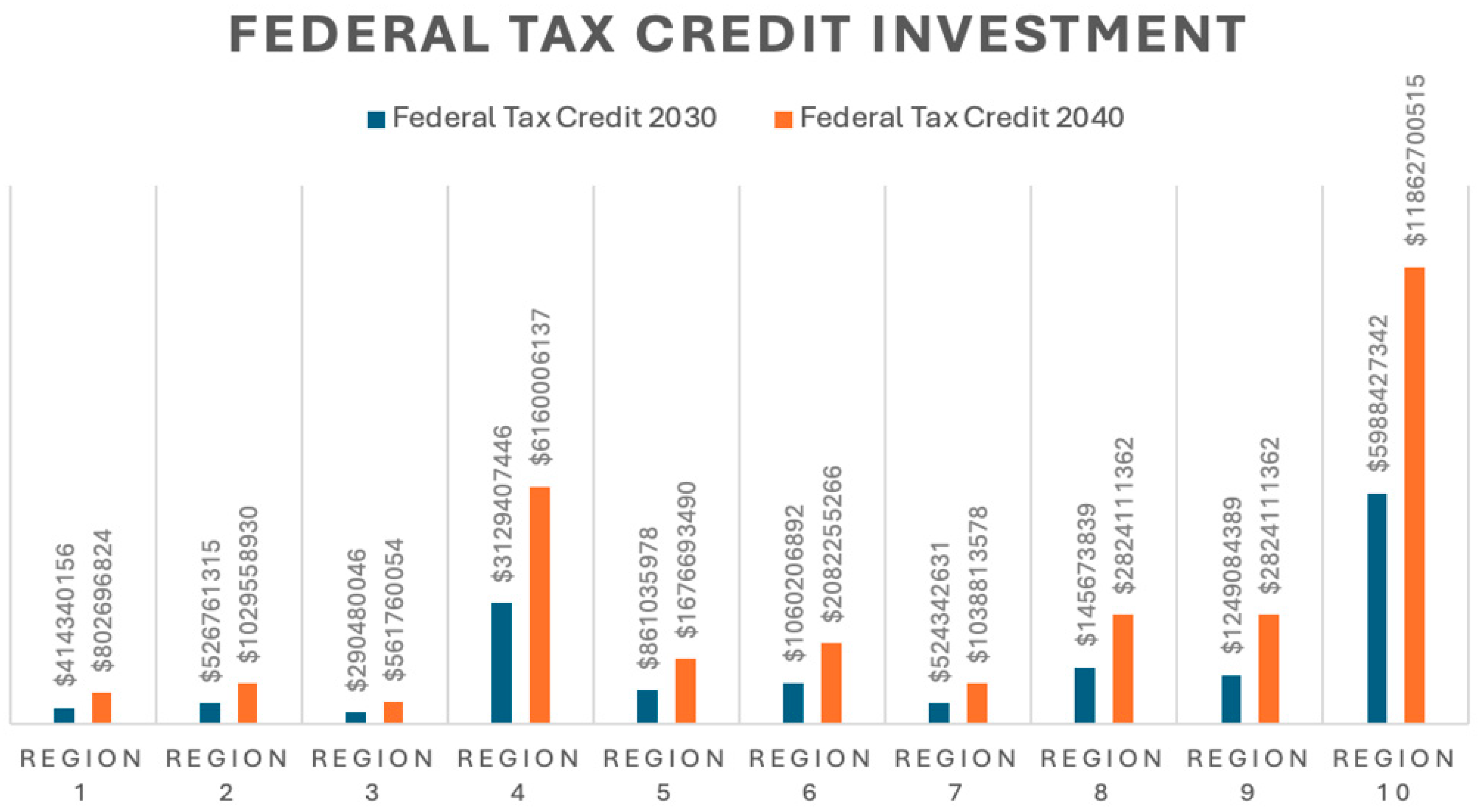

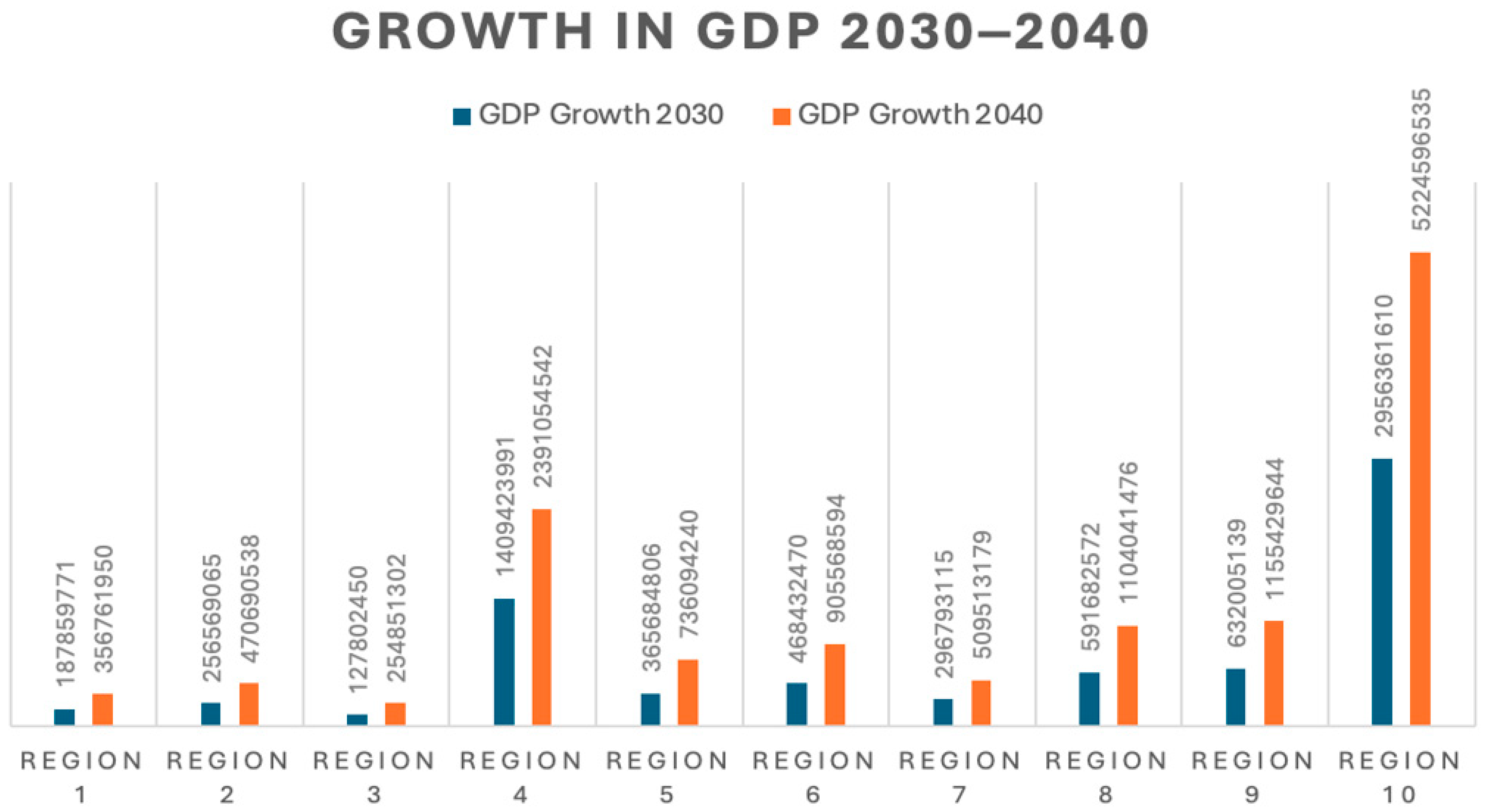

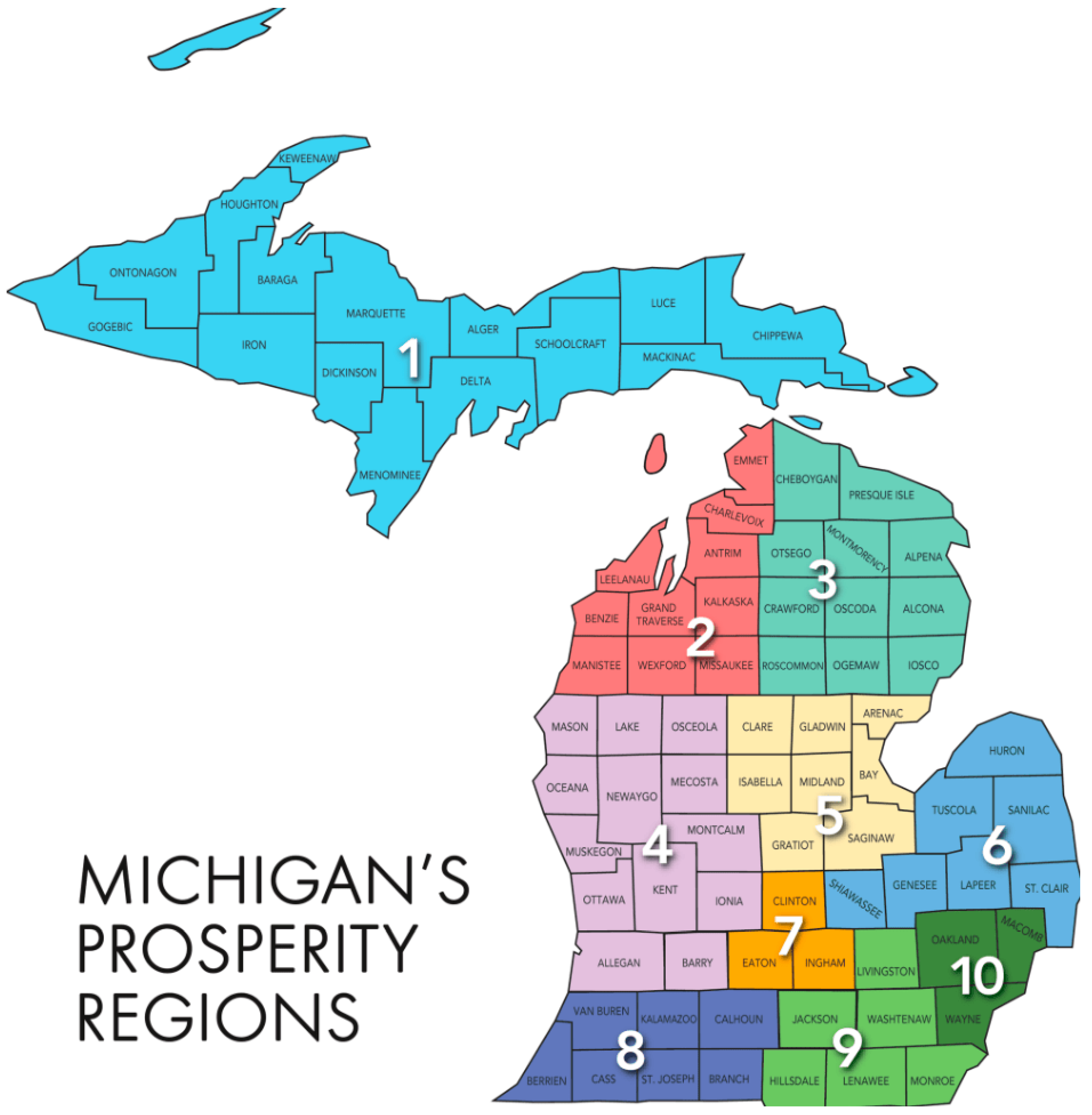

5.1. Economics and the Michigan Healthy Climate Plan

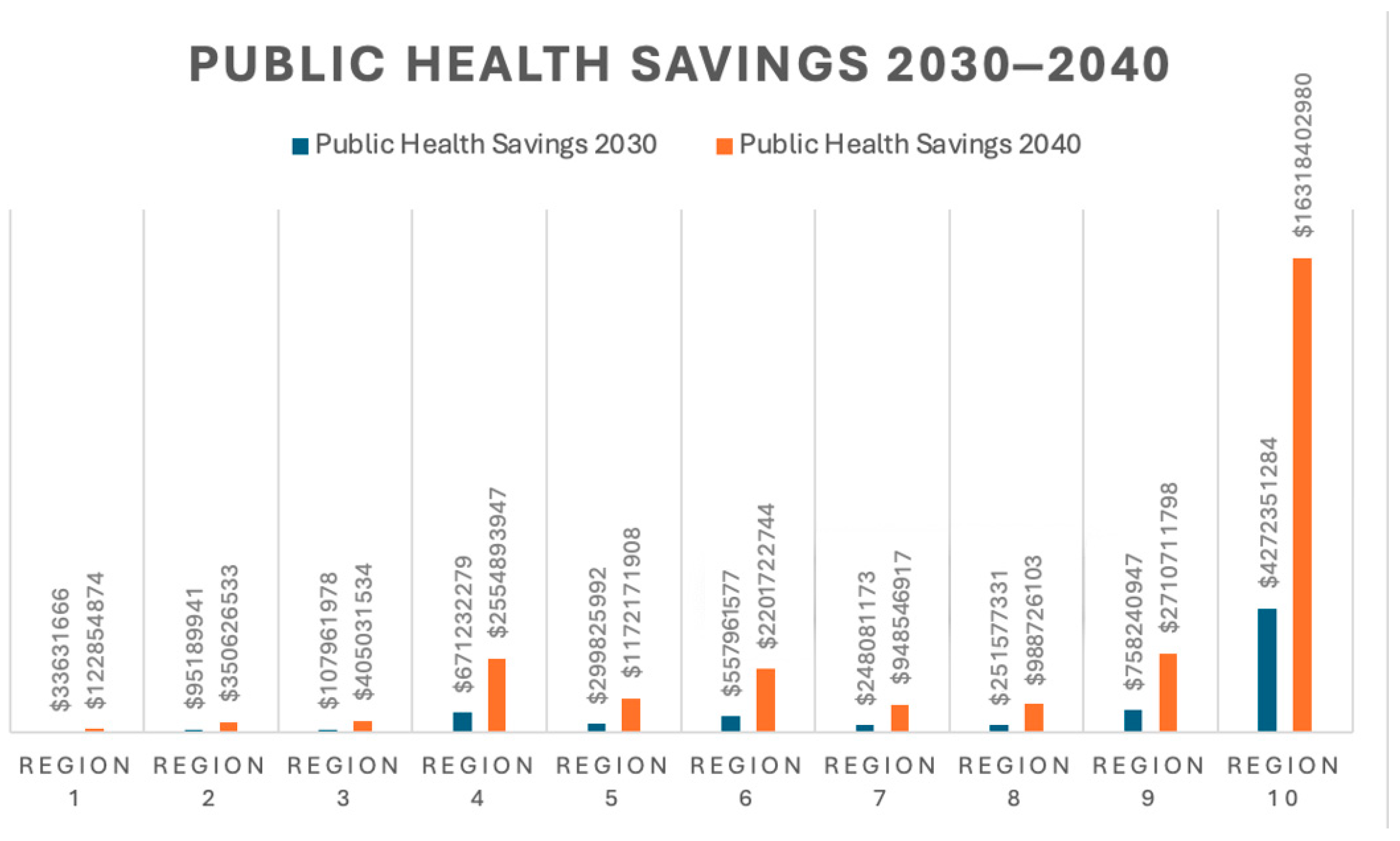

5.2. Health and Wellbeing and the Michigan Health Climate Plan

5.3. Funding the Michigan Health Climate Plan

5.4. Jobs and the Michigan Healthy Climate Plan

5.5. Transformative and Innovative Policy in Action

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Abbreviations

| MHCP | Michigan Healthy Climate Plan |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| NEPA | National Environmental Policy Act |

| IRA | Inflation Reduction Act |

| IIJA | Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

| PFAS | Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| EGLE | Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy |

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| HB | House bill |

| SB | Senate bill |

| PACE | Property assessed clean energy |

| MPSC | Michigan Public Service Commission |

| IRP | Integrated Resource Plan |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

Appendix F

Appendix G

Appendix H

References

- Davenport, C. A Climate Laggard in America’s Industrial Heartland Has a Plan to Change, Fast. New York Times [Digital Edition], 2 July 2023. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/02/climate/michigan-climate-change.html (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Maracci, S. Michigan 2050 Carbon Neutrality Goal Could Be an Economic Engine—If It Avoids a Rush to Gas. Forbes. 2022. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/energyinnovation/2022/02/09/michigan-2050-carbon-neutrality-goal-could-be-an-economic-engineif-it-avoids-a-rush-to-gas/ (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Executive Office of the Governor. ICYMI: New Report Shows Gov. Whitmer’s Clean Energy Legislation Will Lower Costs, Create Thousands of Good Paying Jobs, and Stimulate an Economic Boom. 2024. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/news/press-releases/2024/09/09/icyminew-report-shows-gov-whitmers-clean-energy-legislation-will-lower-costs (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Lioubimtseva, E.; Zylman, H.; Carron, K.; Poynter, K.; Rashrash, B.M.-E. Equity and Inclusion in Climate Action and Adaptation Plans of Michigan Cities. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency. Environmental Justice Timeline. Available online: https://19january2021snapshot.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/environmental-justice-timeline_.html (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Jones, A.C. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Environmental Justice Activities and Programs. 2024. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47920#:~:text=12898%2C%20EPA%20has%20generally%20defined,policies.%2210%20Other%20federal%20departments (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Bullard, R.D.; Mohai, P.; Saha, R.; Wright, B. Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty: Why Race Still Matters After All These Years. Environ. Law 2008, 38, 371. [Google Scholar]

- Executive Order 12898. Summary of Executive Order 12898—Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice In Minority Populations and Low Income Populations. Available online: https://www.archives.gov/files/federal-register/executive-orders/pdf/12898.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- United States Department of Energy. Community Guide to Environmental Justice and NEPA Methods. 2019. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2019/05/f63/NEPA%20Community%20Guide%202019.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Nobles, M.; Womack, C.; Wonkam, A.; Wathuti, E. The Sustainability Movement is 50. Why Are World Leaders Ignoring it? Nature 2022, 606, 225. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-01508-2 (accessed on 26 August 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Brundtland, G. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Dunn, A.D. At the Intersection of Environmental Justice and Sustainability Lies a more Equitable, Healthy Future for U.S. Communities. UMKC Law Rev. 2024, 92, 773–787. [Google Scholar]

- Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. Statute at Large 136 Stat. 1818 – Public Law No. 117–169. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Oloriz, M.; Tong, C.; Ramirez, A.; Shah, N. The Utility of Now: How the IIJA and IRA Are Expediting the ‘Utility of the Future’ Into the Present. Available online: https://www.westmonroe.com/perspectives/point-of-view/utility-of-now-how-iija-ira-expediting-utility-of-the-future#:~:text=In%20this%20sense%2C%20IIJA%20and,mechanism%20to%20catalyze%20this%20change (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2022. Pub L No 117-58. 135 Stat 429. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/3684 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- The White House. Fact Sheet: The Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal Boosts Clean Energy Jobs, Strengthens Resilience, and Advances Environmental Justice. Available online: https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/11/08/fact-sheet-the-bipartisan-infrastructure-deal-boosts-clean-energy-jobs-strengthens-resilience-and-advances-environmental-justice/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Bertrand, S. How the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Work Together to Advance Climate Action. Available online: https://www.eesi.org/articles/view/how-the-inflation-reduction-act-and-bipartisan-infrastructure-law-work-together-to-advance-climate-action (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Saha, D.; Jaeger, J. America’s New Climate Economy: A Comprehensive Guide to the Economic Benefits of Climate Policy in the United States. World Resources Institute, 2020. Available online: https://files.wri.org/d8/s3fs-public/americas-new-climate-economy.pdf?_gl=1*13c9u13*_gcl_au*MTUyMzU2MjQyNi4xNzQ4NjM2Njc2 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Claussen, E.; Peace, J. Energy Myth Twelve—Climate Policy will Bankrupt the U.S. Economy. In Energy and American Society—Thirteen Myths; Sovacool, B.K., Brown, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.; Alfredsson, E.; Westling, N. Climate Change Co-Benefits: A Review. Clim. Policy 2019, 20, 292–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, M. Optimistic Prospects for US Climate Policy in the Biden Administration; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, 2021; Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep30503 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Wang, D.; Mei, J. An Advanced Review of Climate Change Mitigation Policies in the United States. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 208, 107718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahal, S. Detroit Launches $15M Effort to Curb Basement Backups in Flood Prone Neighborhoods. The Detroit News. Available online: https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit-city/2022/02/07/detroit-launches-15-m-program-reduce-basement-backups/6686251001/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Nelson, G. Toxic Great Lakes Algae Makes Michigan Sick. But Remedy May be Near. Bridge Michigan. Available online: https://www.bridgemi.com/michigan-environment-watch/toxic-great-lakes-algae-makes-michigan-sick-remedy-may-be-near (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Ross, I. Canadian Wildfire Smoke Just Blanketed the Midwest—Again. Michigan Advance. Available online: https://michiganadvance.com/2024/05/18/canadian-wildfire-smoke-just-blanketed-the-midwest-again/ (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Fergen, J.T.; Bergstrom, R.D.; Steinman, A.D.; Johnson, L.B.; Twiss, M.R. Community Capacity and Climate Change in the Laurentian Great Lakes Region: The Importance of Social, Human, and Political Capital for Community Responses to Climate-Driven Disturbances. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 675, 993–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graydon, R.C.; Mezzacapo, M.; Boehme, J.; Foldy, S.; Edge, T.A.; Burbacher, J.; Chan, H.M.; Dellinger, M.; Faustman, E.M.; Rose, J.B.; et al. Associations Between Extreme Precipitation, Drinking Water, and Protozoan Acute Gastrointestinal Issues In Four North American Great Lake Cities 2009-2014. J. Health Water 2022, 20, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, R. Michigan Agriculture Faces Impact of Climate Change. WLNS. Available online: https://www.wlns.com/news/michigan-agriculture-faces-impact-of-climate-change/ (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Nickels, A.E.; Clark, A.D. Framing the Flint Water Crisis: Interrogating Local Nonprofit Sector Responses. Adm. Theory Pract. 2019, 41, 200–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobek, J. Stress, Coping, Resilience and Trust during the Flint Water Crisis. Behav. Med. 2020, 46, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmer, R.W.; Reeves, D.M.; Cassidy, D.P. Per- and Polyfluorinated Alkyl Substances (PFAS) Cycling within Michigan: Contaminated Sites, Landfills, and Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water Res. 2022, 210, 117983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, S.M.; Schulenberg, J.W. Impacts of Climate Change on the Environment, Increase in Reservoir Levels, and Safety Threat to Earthen Dams: Post Failure Case Study of Two Cascading Dams in Michigan. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2022, 18, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schot, J.; Steinmueller, W.E. Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation, and transformative change. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1554–1567. [Google Scholar]

- Diercks, G.; Larsen, H.; Steward, F. Transformation innovation policy: Addressing variety in an emerging policy paradigm. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillitsch, M.; Hansen, T.; Coenen, L.; Miörner, J.; Moodysson, J. Innovation policy for system-wide transformation: The case of strategic innovation programmes (SIPs) in Sweden. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1048–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B.; Kivimaa, P.; Ramirez, M.; Schot, J.; Torrens, J. Transformative outcomes: Assessing and reorienting experimentation with transformative innovation policy. Sci. Public Policy 2021, 48, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Governor Gretchen Whitmer. Executive Directive 2020—10. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/news/state-orders-and-directives/2020/09/23/executive-directive-2020-10 (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy. Michigan Becomes a National Leader in Climate Action with New Legislation, Making Progress on the Goals of the MI Healthy Climate Plan. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/egle/newsroom/mi-environment/2023/11/28/michigan-becomes-a-national-leader-in-climate-action-with-new-legislation (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Solar Energy Facilities Taxation Act. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. Available online: https://legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/publicact/pdf/2023-PA-0108.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Executive Office of the Governor. Whitmer Signs Bipartisan Bills to Expand Clean Energy Create Jobs and Lower Energy Costs. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/news/press-releases/2023/07/27/whitmer-signs-bipartisan-bills-to-expand-clean-energy-create-jobs-and-lower-energy-costs (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- US Department of Energy. Property Assessed Clean Energy Programs. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/scep/slsc/property-assessed-clean-energy-programs (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Property Assessed Clean Energy Act. State of Michigan 95th Legislature. Available online: https://legislature.mi.gov/documents/2009-2010/publicact/pdf/2010-PA-0270.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Public Act 106. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. 2023. Available online: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/publicact/pdf/2023-PA-0106.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Public Act 107. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. 2023. Available online: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/publicact/pdf/2023-PA-0107.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Journal of the Senate. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. No. 50. pp. 943–944. 2023. Available online: https://legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/Journal/Senate/pdf/2023-SJ-05-24-050.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Ottawa County. Property Assessed Clean Energy Program. 2024. Available online: https://miottawa.org/dsi/economic-development/pace/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy. MI Healthy Climate Plan. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/egle/about/organization/climate-and-energy/mi-healthy-climate-plan (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Public Act 233. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. Available online: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/publicact/pdf/2023-PA-0233.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Public Act 234. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. Available online: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/publicact/pdf/2023-PA-0234.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Journal of the House. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. No. 28. p. 372. Available online: https://legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/Journal/House/pdf/2023-HJ-03-22-028.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Journal of the House. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. No. 93. p. 2325. Available online: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/Journal/House/pdf/2023-HJ-11-02-093.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Martinez, V. House Democrats Celebrate Signing of Clean Energy Bills. Available online: https://housedems.com/house-democrats-celebrate-signing-of-clean-energy-bills/ (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Clean and Renewable Energy and Energy Waste Reduction Act. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. Available online: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/publicact/pdf/2023-PA-0235.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Public Act 229. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. Available online: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/publicact/pdf/2023-PA-0229.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Public Act 230. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. Available online: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/publicact/pdf/2023-PA-0230.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Public Act 231. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. Available online: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/publicact/pdf/2023-PA-0231.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Community Worker and Economic Transition Act. State of Michigan 102nd Legislature. Available online: https://www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2023-2024/publicact/pdf/2023-PA-0232.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2024).

- Michigan Senate Democrats. Senate Passes Momentous Legislation to Create ‘Clean Energy Future’ in Michigan. Available online: https://senatedems.com/blog/2023/10/26/clean-energy-2/ (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Office of Senator Aric Nesbitt. Nesbitt: Michiganders Can’t Afford Dems’ Radical Energy Deal. Available online: https://newsletters.misenategop.com/w/lUBjFCdpKOtE3lTbOPD8IQ (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Lazo, A. California Isn’t on Track To Meet Its Climate Change Mandates—And a New Analysis Says It’s Not Even Close. Cal Matters. 2024. Available online: https://calmatters.org/environment/climate-change/2024/03/california-climate-change-mandate-analysis/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- California Innovation Index. 2023 California Green Innovation Index. 2023. Available online: https://greeninnovationindex.org/2023-edition/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Baldassare, M. California Is a Model for Climate Change Action When International Efforts Fall Short. 2023. Available online: https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2023/07/california-is-a-model-for-climate-change-action-when-international-efforts-fall-short?lang=en (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Vogel, D. California Greenin’: How the Golden State Became an Environmental Leader; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, A. Silicon Valley Goes Green: The Origin of California’s Climate Regime. Soc. Forces 2022, 102, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy. Michigan’s Priority Climate Action Plan. 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-03/michigan-egle-pcap.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- 5 Lakes Energy. Michigan Clean Energy Framework: Assessing the Economic and Health Benefits of Policies to Achieve Michigan’s Climate Goals. 2023. Available online: https://5lakesenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/5-Lakes-MEIBC-MI-Clean-Energy-Framework-report.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Office of Governor Gretchen Whitmer. Gov. Whitmer, Legislative Leaders Celebrate Passage of FY25 Budget. 2024. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/news/press-releases/2024/06/27/gov-whitmer-legislative-leaders-celebrate-passage-of-fy25-budget (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Michigan Infrastructure Office. Biden-Harris Administration’s Inflation Reduction Act Sparks Job Creation, Results in over $26 Billion in Clean Energy Investments and Projects Across Michigan. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/issues/michigan-infrastructure-office/mio-press-release/2024/08/15/biden-harris-administrations-inflation-reduction-act (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Michigan Infrastructure Office. Department of Energy Awards $18 Million to Michigan to Help Small Suppliers Modernize Their Manufacturing Capabilities. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/issues/michigan-infrastructure-office/mio-press-release/2024/08/15/department-of-energy-awards-$18-million-to-michigan#:~:text=A%20new%20report%20from%20Climate,and%20now%20employ%20123%2C983%20Michiganders (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Clean Jobs American 2024. IRA Drives Clean Economy Job Surge: E2’s Ninth Annual Analysis of U.S. and State Clean Energy Sector Employment. 2024. Available online: https://cleanjobsamerica.e2.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/E2-2024-Clean-Jobs-America-Report_September-17-2024.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Robinson, S.; Freedman, A. Michigan has one of the Nation’s Least Reliable Power Grids. Axios 2024. Available online: https://www.axios.com/local/detroit/2024/04/29/michigan-has-one-of-nations-least-reliable-power-grids (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Michigan Department of Energy, Great Lakes, and Energy. Michigan Is Energized: Report Ranks State 6th in the Nation for Clean Energy Jobs. 2024. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/egle/newsroom/mi-environment/2024/10/25/report-ranks-state-6th-in-nation-for-clean-energy-jobs (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Michigan’s Clean Energy Economic Comeback: How Local Economies in Michigan Are Benefiting from State and Federal Climate Policies; 5 Lakes Energy, 2024; Available online: https://5lakesenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Final-MI-analysis-regions.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Union of Concerned Scientists. On the Road to 100 Percent Renewables for Michigan. 2022. Available online: https://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/2022-04/on-the-road-100-renewable-mi-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- State of Michigan. State of Michigan Prosperity Regions. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/-/media/Project/Websites/mdhhs/Folder3/Folder39/Folder2/Folder139/Folder1/Folder239/Prosperity_Map1_430346_7.pdf?rev=4b907ee644814b6397163752b0c3807e (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Pauli, B.J. The Flint water crisis. WIRES Water 2020, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, D. Consumers Energy Broke Ground on a 1900 Acre Solar Farm in Muskegon County. Available online: https://www.fox17online.com/news/local-news/consumers-energy-broke-ground-on-1-900-acre-solar-farm-in-muskegon-county#:~:text=Consumers%20Energy%20broke%20ground%20on%201%2C900%2Dacre%20solar%20farm%20in%20Muskegon%20County,-Prev%20Next&text=Consumers%20Energy%20is%20building%20their,of%20many%20more%20to%20come (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Davidson, K. Michigan Remains on Top in Clean Energy Projects, New Study Says. Michigan Advance, 2025. Available online: https://michiganadvance.com/2025/01/17/michigan-remains-on-top-in-clean-energy-projects-new-study-says/#:~:text=Compared%20to%20the%20other%20states,receiving%20%2427.84%20billion%20in%20investments. (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Consumers Energy: Environment. Our Plan: To Eliminate Coal Use and Reduce Carbon Emissions 90% by 2040. Available online: https://www.consumersenergy.com/about-us/sustainability/environment#:~:text=Our%20Plan:%20To%20Eliminate%20Coal,to%20redefine%20Michigan’s%20energy%20future. (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- DTE Press Release. Michigan Public Service Commission Approves DTE’s Landmark Clean Energy Plan. 2023. Available online: https://ir.dteenergy.com/news/press-release-details/2023/Michigan-Public-Service-Commission-approves-DTEs-landmark-clean-energy-plan/default.aspx (accessed on 14 May 2025).

| Policy Area | Goal | Strategies and Actions | Effectiveness Cost and Feasibility | Equity Impact | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Justice | Ensure fair access to clean air, water, and energy for all communities |

| High Medium | Medium -High | Ongoing |

| Energy Transition | Shift from fossil fuels to clean energy |

| High High | Medium | Longterm Consumers Energy and DTE Energy plan carbon neutrality by 2050 [Appendix H] |

| Sustainable Agriculture | Reduce GHGs and enhance resilience in ag sector |

| Medium Medium | Medium | Ongoing |

| Sustainability | Promote circular economy and reduce consumption |

| Medium High | Low to high medium | Ongoing |

| Renewable Energy | Scale up solar, wind, and battery storage |

| High Medium | Medium to high | Longterm scaled increases via the Clean and Renewable Energy and Energy Waste Reduction Act |

| Carbon Neutrality | Achieve net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 |

| High High -medium | High medium (design dependent) | Longterm (2050) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schneider, L.U.; Boyd, N. From Laggard to Leader: A Novel Policy Perspective of Michigan’s Preliminary Path to Climate Success. Challenges 2025, 16, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16020027

Schneider LU, Boyd N. From Laggard to Leader: A Novel Policy Perspective of Michigan’s Preliminary Path to Climate Success. Challenges. 2025; 16(2):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16020027

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchneider, Laura U., and Nancy Boyd. 2025. "From Laggard to Leader: A Novel Policy Perspective of Michigan’s Preliminary Path to Climate Success" Challenges 16, no. 2: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16020027

APA StyleSchneider, L. U., & Boyd, N. (2025). From Laggard to Leader: A Novel Policy Perspective of Michigan’s Preliminary Path to Climate Success. Challenges, 16(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe16020027