Abstract

Methodologies for future-oriented research are mutually beneficial in highlighting different methodological perspectives and proposals for extending higher-education didactics toward sustainability. This study explores how different augmented-reality applications can enable new ways of teaching and learning. It systematically investigates how student teachers (n = 18) in higher education experienced ongoing realities while designing learning activities for a hybrid conference and interconnecting sustainability knowings via didactic modeling and design thinking. This qualitative study aims to develop a conceptual hybrid framework concerning the implications of student teachers incorporating design thinking and inner transition into their professional work with future-oriented methodologies on didactic modeling for sustainability commitment. With a qualitative approach, data were collected during and after a hackathon-like workshop through student teachers’ reflections, post-workshop surveys, and observation field notes. The thematic analysis shed light on transgressive learning and a transition in sustainability mindset through the activation of inner dimensions. Findings reinforcing sustainability commitment evolved around the following categories: being authentic (intra-personal competence), collaborating co-creatively (interpersonal competence), thinking long-term-oriented (futures-thinking competence on implementing didactics understanding), relating to creative confidence (values-thinking competence as embodied engagement), and acting based on perseverant professional knowledge-driven change (bridging didactics) by connecting theory-loaded empiricism and empirically loaded theory. The results highlight some of the key features of future-oriented methodologies and approaches to future-oriented methodologies, which include collaboration, boundary crossing, and exploration, and show the conditions that can support or hinder methodological development and innovation.

1. Introduction

The initial concept and foundational perspective that set the direction for the entire study is the current complex challenges in national, regional, and international collaboration between people, institutions, processes, networks, and organizations in formal and informal education to achieve the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs). The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe’s (UNECE) Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) framework 2021–2030 [1] notably emphasizes that participatory and collaborative processes integral to global sustainability efforts demand teamwork, trust, exchange, support, and inspiration, as well as the will to assist and to share. To respond to the critical questions initially raised by Earth4All [2], among others, strategic directions and authoritative dialogues need to involve educational institutions, respond to youth aspirations, and consider relevant quality standards, as well as employ digital learning as an integral tool within a culture of collaboration [3,4] In addition, to improve the infrastructure and operations of educational institutions, research is needed on how to strengthen their collaboration with external actors.

Furthermore, it is crucial to explore how the UN’s SDG 4.7 [5] can be integrated into the curricula of higher-education institutions and extend its outreach to other institutions [6]. The 2030 Agenda is a plan of action for universal and sustainable environmental, social, and economic development. It is made up of 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 4 emphasizes quality education as a prerequisite for sustainable societies and lifestyles. To ensure lifelong learning for sustainable development and achieve a transition to a sustainable society, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) must be a fundamental part of formal, informal, and non-formal education. ESD concerns everyone: government agencies, civil society organizations, and local communities. It is, therefore, incorporated into regulations at all levels of the Swedish education system. Education should promote the development and learning of all children, as well as a lifelong desire to learn. It must also instill respect for human rights and democracy and promote gender equality. ESD lays the foundation for active participation in civic life by explaining how society’s different functions and people’s ways of living can adapt to promote sustainable development. ESD must be available throughout life through formal, informal, and non-formal learning opportunities. ESD is incorporated into governing documents at all levels of the Swedish education system, including the curriculum for the compulsory school and the Swedish Higher Education Act. Children and young people have a critical role in the implementation of the 2030 Agenda, both in formal and informal learning environments. The National Council of Swedish Youth Organizations works to strengthen the participation of young people in decision-making processes related to the 2030 Agenda. The target for SDG 4.7 is to ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, the promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship, and appreciation of cultural diversity. Academia provides new knowledge and tools through research and cross-sectoral collaboration [5].

The research question focuses on challenges associated with integrating didactic models and design thinking with inner dimensions for educational development in the field of teaching and learning for sustainability. How knowledge related to sustainability is transformed into higher-education teaching and learning, including its outreach, is highlighted. This qualitative study aims to develop a conceptual hybrid framework concerning the implications of student teachers incorporating design thinking and inner transition into their professional work with future-oriented methodologies on didactic modeling for sustainability commitment. Therefore, the research question sheds light on what the critical perspectives on higher-education didactics for sustainability (HEDS) practices are in teacher education, with emphasis on student teachers’ experiences of learning affordances in future-oriented methodologies (FOM) as an educational development approach towards sustainability commitment.

2. Background and Context

In 2022, the Innovation Centre at Malmö University hosted a “Stormathon” involving international student teachers from the Teaching for Sustainability (TfS) course [7]. Given this context, the course leader (also the author) contacted the innovation center. This collaboration offered a broader context to examine how student teachers, during the Stormathon, were tasked with developing new eco-reflexive learning activities for the forthcoming global CEI 2024 conference. This conference was planned to be conducted in a hybrid format, with the aim of optimizing learning activities for the target group, consisting of students aged 13–19 and their teachers from some 20 countries (see Box 1). Earlier workshops and seminars in the TfS course equipped the student teachers with technical, pedagogical, and subject knowledge related to the main concepts shaping the CEI 2024 conference. Notably, the TfS teacher did not actively participate in the workshop activities or in the students’ subsequent reflection tasks, which were part of their coursework.

Box 1. Case CEI 2024.

Case CEI 2024 conducted by student teachers at the Stormathon Innovation Hub

Learning Affordances Reclaiming the New Normal and Open Digital Transformation of Sustainability Education

Our societies are facing broad sustainability challenges, and it is crucial that we develop learning opportunities that prepare us for an uncertain future, enable us to deal with complex transdisciplinary issues, enable us to collaborate, and empower us to take initiative and act in society.

Caretakers of the Environment International (CEI) is a worldwide network of secondary-school teachers and students who are actively concerned about critical sustainability issues and who are willing to do something about these issues through “non-formal” education activities and action-taking. CEI wishes to advance awareness of the urgent knowledge formation in professional networks, where expertise on pedagogical development of hybrid solutions and digitization of learning moments is shared. Before, during, and after the hybrid conference CEI 2024, the network challenges normative education for sustainable development (ESD) and enriches and rewards innovative collaboration between different actors in society. The CEI requests a hybrid conference that implements eco-reflexive Bildung-oriented sustainability activities, creating critical knowledge capabilities among school youth and their teachers worldwide. The CEI 2024 activities should promote critical eco-reflexive learning towards sustainability so that all participants can independently define issues and details about the projects on which they want to work.

Challenge statement

How could an all-day program look like for one of the days during the conference, focusing on how we can break through deep-rooted normative learning and teaching patterns and encourage eco-reflexive thinking to catch sustainability learning affordances inspired by non-formal (i.e., grassroots) organizations as a foundation towards sustainable development?

The program must consider the hybrid format and the target group of both school youth 13–19 years of age and their teachers.

This paper analyzes the reflections of the students during and following a two-day Stormathon workshop (Figure 1). The workshop took place during the autumn semester of 2022 as part of a Teaching for Sustainability (TfS) course for international student teachers in Sweden.

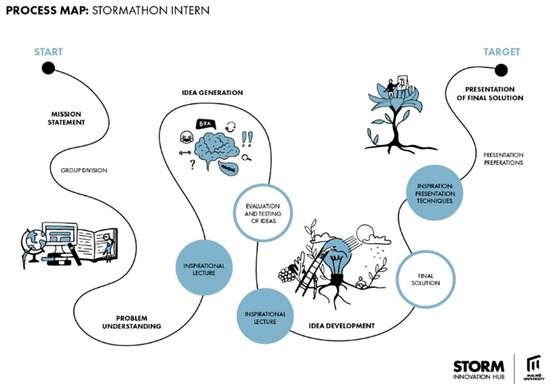

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework for the case CEI 2024 process applying Augmented Reality (AR) in Augmented Learning (AL) environments is captured in this process map of Stormathon.

The Stormathon Workshop

The Stormathon serves as a pedagogical model for the entrepreneurial development of innovative ability, with the objective of creating new ideas and options for active learning [8,9]. During the workshop, participants were grouped into teams and guided through various exercises by experienced process leaders and innovation coaches. The goal of the Stormathon workshop was to plan activities for the Caretakers of the Environment International (CEI) meeting, scheduled for summer 2024 in a hybrid format. The CEI 2024 case, titled “Learning Affordances Reclaiming the New Normal and Open Digital Transformation of Sustainability Education” (see Box 1), exemplifies how virtual exchanges can be implemented in higher education to foster collaboration with youth and teachers in society [3,10,11,12].

3. Theoretical Framing

In some recent systematic reviews of pedagogy of emerging technologies during the era of digitalization and artificial intelligence, cases presented (even in specific discipline subjects) are relevant to the current study and in the context of sustainable development for education in the new era, according to [10], in view of the evolving and vast studies. Chiu [10] found that AR and VR applications were the most investigated of the identified types of technologies used in chemistry education, while the main areas of focus were associated with virtual laboratories, visualization and interaction with subject structures, and practical activities in the classroom. The evidence presented in Chiu’s study also indicates the promising applications of artificial intelligence and learning analytics in analyzing student feedback and behavior, assessing student understanding of subject-specific concepts, and investigating student reasoning and cognitive processes during interpretation tasks. Areas requiring more investigations, research, and potential future applications, accompanied by pedagogical implications of education for sustainable development, will also be identified based on the evidence presented in this study.

3.1. Design Thinking

The theoretical origin of the Stormathon workshop lies in the field of collaborative learning, which includes the acquisition of generic skills in team learning processes [13]. The Stormathon workshop utilized the Input-Process-Output model [14], which explores how experiences, behavioral beliefs, problem understanding, idea generation, and assimilations of team members influence the team’s collective functioning and their perception of innovative skill acquisition [15]. The Stormathon workshop was based on applied design thinking [16,17]. Moving beyond more conventional discussion or reflection fora in interactive platforms, design thinking [18] adds the dimension of individual or collaborative creative processes and can be used to focus on action for concrete cases. In relation to the adopted approaches in this study regarding education for sustainable development, a recent study by [19] explored how the use of design thinking through transformative learning is nurturing sustainability changemakers. Their findings show that the design supported developing a sustainability mindset, sustainability literacy, transversal skills, and creative confidence.

3.2. Teachers Re-Contextualizing Powerful Knowings

Teaching has evolved beyond merely imparting knowledge to the next generation. It is undergoing a transformation [20], becoming a design science, and there is a need to re-purpose higher-education didactics for sustainability [6,21]. Like architects and other design professionals, teachers are required to devise creative and evidence-based methods to improve their practice. Although teachers design and test new ways of teaching using technology-enhanced learning [10,11,22] to support their students, teaching is not recognized as a design profession [18]. As a result, teachers’ discoveries and inventions often remain localized. By altruistically demonstrating and communicating their best ideas as structured pedagogical patterns [21], such as “didaktik modeling” (see below), teachers could collectively develop vital professional knowledge to be used as relevant and powerful knowings [23,24,25]. Teachers’ professional development often goes unrecognized ([26], as do the innovative ideas they discover in their everyday teaching practice. Their proven experiences, which are valuable and should be shared and communicated to other teachers to build didactic models based on mutual ideas, could be re-contextualized, as suggested by [27]. This re-contextualization could occur via didactic modeling, emphasizing locality, decontextualization, decision-making, and argumentation. There is a call for more research in teacher professional development programs and teacher training workshops to support school teaching, advance the professional scholarship of teaching, and theoretically reinforce and deepen design thinking [19].

3.3. Didactic Modeling

Virtual exchange arrangements are online people-to-people actions that promote inclusive dialogue and flexible talent training. They generate opportunities for youth and teachers worldwide to access high-quality international and cross-cultural education, both formal and informal, without the need for physical mobility [28]. While virtual dialogue cannot fully replace the benefits of physical mobility [11], the ability for participants to meet and engage in debate in virtual exchanges allows them to reap some of the benefits of international educational experiences. Digital platforms enable a response to global mobility restrictions due to visas, funding or time constraints, and the need to reduce greenhouse emissions from international travel [29].

As a tool for didactic modeling, ongoing realities (OR) [30] can be viewed as a contemporary concept that contributes to the development of augmented learning within a framework of Augmented Realities (AR) in comparison with Khairani and Prodjosantoso [12], acting as a catalyst (Figure 1). Simultaneity, presence, and ongoing are key terms that follow this process in all its aspects [31]. The learning affordances provided by comprehensive experiences in both physical and digital rooms allow for the combination of synchronous and asynchronous modalities [10,32,33,34]. This gives participants greater freedom to explore at their own pace, depending on their needs or interests.

This approach is seen as a form of transgressive learning, highlighted by Lotz-Sisitka et al. [35], offering a learning experience that transgresses boundaries and aims to establish new ways of thinking and knowing. Therefore, transformative, transgressive learning includes learning encounters with elements that are not yet present, emerging disruptively or seamlessly via a process in open systems [35].

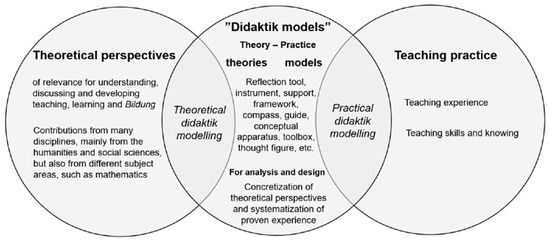

Didactic modeling is relevant to teachers or student teachers using didactic models not only to systematically design and analyze their teaching but also to connect with formal research-related activities (cf. [36]). “Didaktik modeling” ([37], p. 253) refers to didactic knowledge, which involves the systematic use and development of didactic models in teaching practice. By working systematically with praxis-based didactic models in practice, sometimes in collaboration with researchers and as outreach, opportunities for the teachers’ systematic development of their teaching can be created (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Didactic modeling illustrated by sustainability teaching arrangements in school ([37], p. 253).

3.4. Bridging Theoretical Perspectives with Practical Didactic Modeling

To prevent practice didactics from becoming superficial, the practical periods in teacher education could be arranged in transdisciplinary themes and analyzed in terms of intuitive action [38,39]. Case-based work is an approach that allows researchers to bridge more theoretically oriented elements of the curriculum with opportunities for practice and action-oriented learning. The case method applied in the Teaching for Sustainability course, as outlined in the present study, involves student teachers analyzing hybrid and subject-didactic models, including a detailed discussion of complex, contextual teaching situations [32,40]. The method considers that learning takes place when knowledge is constructed within social contexts, and participants’ experiences are central to the communication that ensues. By grappling with the dilemmas presented in the case and collectively reflecting on these dilemmas, new understandings can be created [41]. In that way, recognizing integrated inner–outer transformation in research, education, and practice [42], an essential vehicle for bridging the SDGs with the inner development goals (IDGs) is made accessible [26].

3.5. Competencies for Advancing Social Transformations to Sustainability

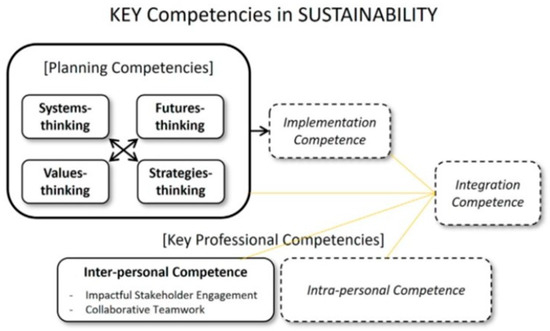

The findings of Redman and Wiek’s study [43] highlight the capabilities of change agents to advance social transformations towards sustainability [19]. They outline a framework of eight key competencies in sustainability (Figure 3), which are broadly applicable to sustainability education and operationalization across disciplines, learning settings, and global contexts.

Figure 3.

Unified framework of competencies for advancing sustainability transformations centered on 8 key competencies in sustainability with 5 established (bold) and 3 emerging (italic) and complemented by professional competencies ([43], p. 7).

The unified framework of key competencies in sustainability links science, education, and society. It is designed to be tested in real-world problem-solving settings [44], contributing to the intersectional effort to expedite transformations toward the SDGs (cf. [26,45].

This study employs this framework as a lens for analyzing the results. Redman and Wiek [43] underscore a fundamental need for the scholarly community to unite and better coordinate their efforts, the necessary advancements in research, and the development of emerging competencies. This study could potentially complement these efforts and help overcome the current fragmented structure of the field. It calls for immediate research, paving the way for more robust progress.

4. Method

Augmented learning (AL) is augmented reality that is used for learning. Augmented learning could be seen as an on-demand learning technique where the environment adapts to the learner. As augmented reality asks students to become active participants in their own learning, it can make them more interested and engaged in the subject matter [12]. Educators can use augmented reality in their classrooms to engage their students, reinforce information, and excite them about learning. AR is created by integrating digital information into the real world. Compared to virtual reality, augmented reality as a heightened version of reality additionally generates immersion, participation, and interaction [10,11]. Providing remediation on-demand can give learners a greater understanding of a topic, stimulate discovery and learning, and enable them to interact by initiating hybrid contexts for an in-person conference. Hybridity means that learning is highlighted based on these different aspects, which contribute to the teaching obtaining important resources for the students’ knowledge formation. The concept of hybridity explains how people in a certain context use several different mediating resources to create meaning and to understand the world. Understanding can then take place in a third space, limiting for or beneficial to learning depending on the collaboration between different classroom contexts and forms of knowledge content [46]. Sometimes, these parts conflict with each other and then risk inhibiting learning, which can thus be considered based on conflicts, tensions, and diversity [32]. In this study, the intention is to create hybrid contexts as “the third space” based on how teacher-students can contextualize knowledge content by presenting a conference program on a sustainability theme with learning activities that work in relation to the knowledge concept at simultaneous in-person and virtual meetings.

4.1. Future-Oriented Methodologies Supporting Inner Transition and Sustainability Commitment

The foundational basis in this study regarding the methodology employed for redesigning higher-education didactics for sustainability (HEDS) is influenced by Nordic and German didactic theory and Dewey’s [47] pragmatic philosophy and relies on five forms of democratic participation [48]. This is needed for the students to become a part of a democratic-based education and political decision-making. Therefore, communicative reflection tools such as the deliberative discussion (1) are employed. Together with agency (2) in terms of planning the context, environments, and artifacts in education; creativity (3) allowing educative moments of experience-based knowledge; critical reflections (4) on trends, traditions, and science models; and authentic participation (5) for building relevance of knowledge in education, i.e., meaning-making, the educational changes and dynamics are supported. Therefore, the HEDS methods employed in this study are grounded on offering the participants the ability to feel confident in discussing alternative ways in a safe environment, planning for inclusion, thinking and acting outside the box, rethinking/reflecting, and being true to themselves.

For a comprehensive understanding of the educational dynamics and to support the proposed changes in higher-education didactics, the broader approach that describes sustainability commitment as a multidimensional didactical approach as in the model by [49] could be recognized. That integrates key aspects, including intellectual (e.g., scientific rigor and critical thinking), emotional (e.g., emotional responses, relationships, personal engagement), and practical aspects (e.g., practical activities and actional skills).

4.2. Cultivating Sustainability Commitment through Transformational Learning Mindsets

The workshop was designed to utilize the innovation sprint format [50] to promote collaboration, communication, and co-creation skills to stimulate idea development in a playful way [51]. A Stormathon, spanning two days, is aimed at equipping the students with practical innovation methodologies in a responsible way [7]. Inspired by traditional hackathons, experienced coaches and external inspirational speakers lead the student teams through a process where they develop an innovative concept in real time to address an unsolved problem or fulfill an unmet need. The activity is structured into three parts: problem understanding and needs assessment, idea generation and development, and presentation and pitching techniques. At Malmö University, these workshops are typically integrated into a course that requires an innovative approach. This approach aids students in developing their problem-solving skills, recognizing opportunities to run their businesses or projects, and equipping them with a foundation of innovative tools and approaches that can be applied in design thinking and planning for reality-based action-taking. The workshops aim to offer equal conditions and opportunities for personal development, irrespective of the student’s background, leadership abilities, or conditions for taking initiative.

4.3. Participants

The class consisted of 1 male and 17 female student teachers organized into four teams, with 3–5 individuals per team. These teams were formed by the teacher rather than by the students themselves. The surveys and other data collection methods employed for this study (see Scheme 1) did not gather demographic information on the participants or focus on their diversity. Nonetheless, the data reflects a multicultural representation of experiences, with the students aged between 20 and 28 years hailing from countries such as Austria, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Japan, Switzerland, and Spain. Their interactions were conducted in English, which was not their native language. The students specialized in primary and middle-school teacher training.

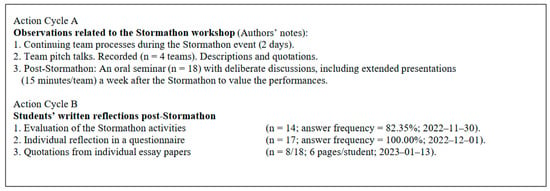

Scheme 1.

Overview of the data collection: Action cycles of interaction and reflection.

4.4. Data Collection

The data collection took place in the autumn semester of 2022. The data were collected through surveys and questionnaires completed by the workshop participants, who were students enrolled in the Teaching for Sustainability (TfS) course. Additional data were collected through the students’ perceptions as articulated in individual essay papers (see Scheme 1). The surveys and questionnaires were completed in conjunction with the workshop, with data collection spanning two action cycles. The data collected during Action Cycle A highlighted interaction and reflection, while the data collected in Action Cycle B focused on written documentation (Scheme 1). Upon conclusion of each action cycle, the students’ perceptions were gathered through both individual and focus group reflections.

4.5. Data Analysis

The data underwent thematic exploration through qualitative analysis. This form of thematic analysis [52] emphasizes the use of hierarchical coding but balances a highly structured process of analyzing textual data with the flexibility to cater to the study’s requirements [53]. A coding template was developed for the validation of oral seminar activities, individual reflections, and written post-validation questionnaires and papers. To define an initial coding template, an open coding approach was used to create an initial coding template generated from a subset of the data material. These codes were subsequently revised and refined based on subsequent transcripts in an iterative reflective process. All quotes were carefully read, analyzed, and then slightly edited for readability. Any information related to a specific person was replaced with a non-identifiable descriptor. All data collected were reviewed securely and anonymously to ensure accuracy.

The analysis of the empirical material can be described as abductive analysis [54], which involves identifying descriptions of the material in relation to the research aim. The process alternated between theory-loaded empiricism and empirically loaded theory (cf. Figure 2), revealing qualitative patterns. The analysis followed the interpretation paths of close reading and listening to identify distinctive descriptions and to critically problematize distinctive categories of descriptions in relation to earlier research and concepts [55,56]. A consistent analysis was performed, considering the didactic modeling, which resulted in a conceptual focus [37]. Empirical and theory-based interpretation paths were characteristically intertwined. Quotations were selected for their clear exemplification of the categories of descriptions in the data gathered.

5. Findings

This section presents empirical findings from the study, with a focus on the insights gleaned from multiple rooms of didactic modeling. The analysis identified a variety of key sustainability competencies [43,57]. The focus of the study was to explore how augmented learning via design thinking [19], could be integrated into the didactic modeling of teaching for learning activities in a program and a hybrid conference. The approach was not to measure learning objectives in non-traditional teaching, nor to evaluate the student teachers´ perception of different artifacts or to determine the learning benefit. Rather, the study explored multiple forms of knowing, thus challenging the norm and transformative education in general [35].

Data were exclusively obtained from the analysis of the approaches used by the student teachers and ideas tested through the discussion with them. The thematic analysis [52,53] shed light on transgressive learning and a transition in sustainability mindset (cf. [58]) integrating inner development goals [26,42]. Consequently, the five following categories of descriptions appeared. Reinforcing sustainability commitment evolved around the categories of being authentic (intra-personal competence), collaborating co-creatively (interpersonal competence), thinking long-term-oriented (futures-thinking competence on implementing didactics understanding), relating to creative confidence (values-thinking competence as embodied engagement), and acting based on perseverant professional knowledge-driven change (bridging didactics) by connecting theory-loaded empiricism and empirically loaded theory [37]. Each of these categories collaboratively contributes to the problem-solving process and is detailed below. To a certain extent, these categories also correlate with some key sustainability competencies [43,59].

5.1. BEING Authentic with Intra-Personal Competence for Sustainability Commitment via Relationship to Self

Authenticity plays an important role in the development of agency, drawing on Bandura’s ([60]) theory of human agency and considering revealed relationships [18]. The anthropocentric perspective often overshadows the multidimensional complexities and political and social structures [59,61]. Consequently, the bonus frequently falls on the individual to construct adequate modes to establish and visualize relationships between the dimensions of sustainable development [26]. While this responsibility could be experienced as an indirect burden on the student teachers, they demonstrated responsiveness and navigated through the complexities and simplicities in dealing with the authentic and reality-based case [43]. They gained motivation from a power-critical perspective, underscoring the significance of space for participants’ self-understanding [42]. These challenging conditions reveal the potential of education and its crucial role in making sustainability challenges understandable, especially when they are often invisible.

Unsurprisingly, the students referred to the three fundamental questions in didactics—why? what? and how? [62]. The question of why a particular topic should be taught is of paramount importance. This ensures that not only the teacher but also the students understand the relevance of learning that specific topic. The student teachers grasped the significance of the sustainability-centered case, CEI 2024. They had previously focused on the theoretical perspectives relevant to understanding and developing sustainability teaching arrangements and had successfully passed exams on theoretical didactic modeling earlier in the TfS course [25]. To attain a common foundation, the student teachers also studied and discussed the book The World We’ll Leave Behind: Grasping the Sustainability Challenge [63]. During the Stormathon workshop, the student teachers were tasked with concretizing these theoretical perspectives and practically applying the profession-developing subject didactics (cf. [37]). Given the hybrid format of an all-day program in the CEI 2024 conference, the student teachers were required to thematically integrate these theoretical perspectives into an analysis, in conjunction with systematically proven teaching experience [64], to use practical didactic modeling (see Figure 2) for the case design.

The student teachers highlighted that sustainability, as a topic, offers many opportunities for transdisciplinary teaching, transcending the boundaries set by school subjects, norms, and the classroom itself [44,65]. For example, while sustainability is usually linked with the subject of science, many other subjects—such as art, geography, civic science, and psychology—also contribute to Global Learning for Sustainable Development (GLSD) [4]. According to one student teacher, the topic is highly suitable for a project week, incorporating all subjects. A Whole Institution Approach (WIA) [25,66,67] was proposed, encompassing teaching approaches and didactic methods aligned with GLSD. Furthermore, schools need to ensure the sustainability of their resources and provide further education for their teachers and other staff, therefore integrating sustainability into every aspect of the decision-making process. A Whole-School Approach (WSA) to sustainability could then serve as a catalyst for education renewal in times of distress [68]. Additionally, the student teachers suggested that schools cooperate with local government and other partners, such as institutions:

I would like to analyze the Stormathon. I found it like an activity I participated in when I was in high school, which was about developing a product based on a local company’s story. Although the themes are different, the two have one thing in common: they allow students to participate in a real process that requires a certain amount of responsibility and demands. And students could usually not be involved on a large scale, which is very creative. I felt that the contribution of being able to come up with ideas for the actual project enables students to motivate themselves by imagining the situation in which their ideas are being carried out. It is good for spontaneous learning and sustainable goals.(Student Teacher 1)

The quotation above acknowledges the importance of authenticity and agency in establishing powerful sustainability. By positioning the students as agents, on the planner side rather than the passive side, authenticity enables them to learn spontaneously and creatively, which they cannot achieve in the classroom:

Subsequently, everyday life or also the classroom could be redesigned together in a more sustainable way. Didactic principles that must not be ignored are definitely inclusion, participation, and tolerance: every opinion should be heard and accepted, and a pleasant and appreciative learning atmosphere is essential. The diversity of personalities and opinions should be seen as an enriching opportunity for development, which is also important to make clear to the children. In these processes, children also learn how important empathy is. I could deepen my knowledge about sustainability in the classroom.(Student Teacher 2)

The students showed both appreciation and disappointment concerning the Stormathon workshop. However, they acknowledged that they appreciated the practical settings and enjoyed the critical discussions organized for them in this context. The drawbacks exemplify the student teachers’ perception that the content was not tailored to them as a target group. They thought that the workshop was not congruent with SDG 4.7 and suggested that the topics of teaching/education for sustainability should have been given more prominence. Individual questionnaire quotes will follow:

I think it was nice, in general, to have a workshop and to work together in a team in such an intense way. But, unfortunately, it felt like they missed the point—they didn´t see us as a target group. I was missing the education part/input a bit. And for me, it was too much about economics and stuff like “advertisement.” So, I would continue having these workshops, but I would clearly talk about the target group, the correct focus and the goals of it (in advance—with the Stormathon team). I still learned a lot from it, so don´t worry:)(Student Teacher 4)

Many students highlighted the challenging situation and suggested improvements to the workshop to streamline the process during the challenge, aiming for more efficient solutions for the authentic case. These aspects, in addition to the critical eco-reflexive statements made by the students, need to be considered to ensure adequate content and co-design for similar workshops in the future.

The views of all student teachers are valued and deemed valid in engaging contradictions and seeking out new forms of agency. These can be identified via various expressions of agency, including resistance, critique, explanation, reframing, envisioning, committing to actions, navigating power relations, and taking transformative action. According to Lotz-Sisitka et al. [35], this provides a useful means of reflexively reviewing the processes and outcomes of transformative, transgressive learning, irrespective of disciplinarity.

5.2. COLLABORATING Co-Creative Visioning with Interpersonal Competence via Respectful Critics of the Process

The students demonstrated values-thinking competency as they mapped, specified, and negotiated sustainability values [69,70]. They also questioned why the Stormathon Hub does not incorporate sustainability into their work. In addition, one student teacher highlighted that “the Stormathon Hub tries to be super innovative, but then they should also be modern and work more digitally using, for example, websites like Microboard or, at least, draw and write on computers or iPads.” This recommendation highlights the students’ strategic-thinking competency; they recognized complex problems, analyzed the current state, including its historical context, and crafted future sustainability visions (cf. [59]):

Talking about being innovative—and this is just my personal opinion—being innovative is related to the future. At the same time, [the] future is related to climate change and sustainability. So why does the Stormathon Hub not connect their work with actually being sustainable? For me sustainability is more than having the SDGs printed out on pillows.(Student Teacher 4)

In a more critical analysis, the focus shifts to interpersonal competency and collaboration through the different stages of the problem-solving process at Stormathon. However, the students questioned the reliability and validity of these aspects, noting a discrepancy between claims and their experiences. The absence of integrated problem-solving competency was evident [59]:

Another thing is that I was literally shocked at how much staff was involved in this whole workshop. I think it is not necessary to have around 10 adults taking care of around 15 students while they are working. Honestly, don’t they have something else to do? Most of the time they were more disturbing than supporting our working process by interrupting.(Student Teacher 4)

Nevertheless, the median student evaluation seemed to indicate a reasonably empowering experience and learning outcome (score 5 out of 6). Many students expressed satisfaction with the entire process of solving the CEI 2024 case. Reflecting on hybridity connected to the case, a valuable lesson emerged from student evaluations: designing a third space (cf. [32]) for future hackathons, considering a blend of in-person and virtual learning. Most of the students appreciated that the Stormathon allowed them to take responsibility for their own learning (a median score of 5 out of 6). They effectively managed the teamwork by balancing individual contributions while collaborating to develop innovative concepts. Their diverse methods and mixed ideas hold promise for the future:

Positive or negative? My team worked independently. The cause of this independence, however, might have resulted out of very broad and not structured tasks and questions given by the Stormathon team.(Student Teacher 7)

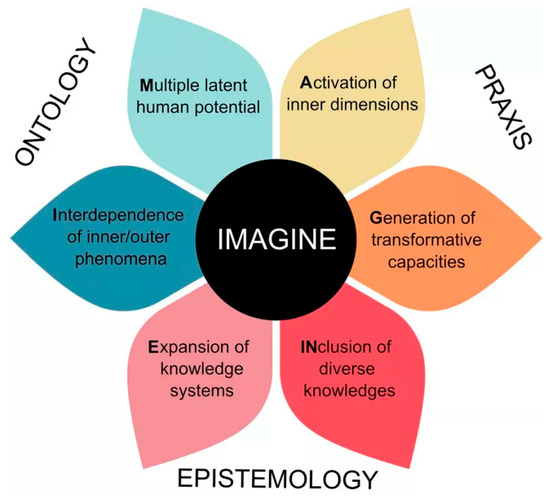

The independence resulted in interdependence among inner and outer phenomena across individual, collective, and system levels, as well as the multiple latent human potential to enable transformative change within each of them were recognized (cf. [42]). The quotations mirror that the sustainability content took a back seat to the hackathon process. Still, they also illustrate that the students had opportunities to develop future-thinking competency through the iterative processes integrated to complement the hackathon format. The students valued the exchange of reflections and feedback from their fellow students, as they shared their created future scenarios with non-interventions [69,70] during class discussions. Recognizing activation of inner dimensions, the student teachers shifted focus from challenging disconnection moves toward the qualities in relationships. Therefore, the generation of transformative capacities took place (cf. [42]) through intentional practices.

I would have liked to have more space to talk about design aspects, as in room or conference design, or how the breaks and lunches are supposed to look like. I also felt like the day after the pitch, when we discussed the proposals in class, all teams had more freedom and time to present, and all ideas came across better because we focused on the content. With the pitch, it was more about “selling yourself”.(Student Teacher 8)

The importance of investigating the dimension of epistemology is stressed, and inclusion of diverse knowledges and expansion of knowledge systems (cf. [42]) are requested by the student teachers. Therefore, the key characteristics of the emerging field of inner transition, existential resilience, existential sustainability, and personal spheres of transformation deserve increasing attention also in teacher education [42]. Unpredictably, the empirical data in this study has, in its analysis, recognized a reinforcement in the identified six key characteristics of inner transformation, which are framed and organized under the acronym IMAGINE (see Figure 4) by Ives, Schäpke, Woiwode, and Wamsler [42].

Figure 4.

IMAGINE: systematization of the six core characteristics of inner transformation and inner–outer change processes, organized under the dimensions of ontology, praxis, and epistemology. All six characteristics are entangled, intertwined, and interdependent ([42], p. 2778).

An important lesson drawn from the participants’ evaluations is that hackathon-like workshops involving professional facilitators need to be conducted with pedagogical anchoring. The organizing team of teachers and instructors must maintain a subject-didactic modeling focus to prevent ambiguous learning situations and frustration [71]. This finding aligns with results from other studies that emphasize key competencies in integrated problem-solving competency for sustainability (cf. Figure 3; [59]). Integrated problem-solving competency entails the ability to apply collective problem-solving procedures to complex sustainability problems. This involves developing viable action plans and successfully implementing sustainability strategies through collaborative and self-directed methods.

5.3. THINKING Long-Term-Oriented Futures-Thinking with Competence on Implementing Didactics Understanding via Complex Awareness

Critical re-contextualization unfolded through a series of various flow steps, preparing the pitching of new ideas. During the Stormathon, ongoing observations revealed the students’ fluctuating attitudes—swinging between hope, frustration, and goal completion. Their belief in the process enforced a sense of obedience, leading them to comply with explicit instructions or orders from a person in “authority”, in this case, the workshop facilitators:

Preparing the conference, in general, the methods were a good idea, but putting them in practice was not that balanced. More focus on us becoming teachers—the target group. Sometimes it felt like they were talking more about start-ups than about educational activities, didn´t really learn anything new… it sometimes felt a bit overwhelming.(Student Teacher 5)

Some of the students criticized the working methods and the learning activities at the Stormathon workshop. They felt that these methods did not adequately reinforce the learning objectives aimed at developing critical knowledge capabilities to concretize the conference concept in alignment with their assigned task. For instance, one student emphasized that the topic and the subject content needed to be central:

To be honest, I did not enjoy the working at Stormathon really much for several reasons. First, I think everything is just super superficial, the actual thing and topic is pushed in the background. Instead, we wasted our time to doing the same task, over and over again and writing on an indescribable and disproportionate amount of Post-its. This time should be used for talking about really important stuff, for example sustainability and the current and upcoming global issues!(Student Teacher 4)

However, most students perceived this issue as rather confident. When asked whether the Stormathon had developed their ability to solve the challenges posed by the CEI 2024 case, the responses revealed a relatively high median score (of 4.5 out of 6) of 14 respondents out of 17 providing affirmative answers.

The assessment methods used during the Stormathon, for example, the final pitch, varied in their ability to demonstrate their achievement of a good conference concept. Some students expressed that the entrepreneurial approach prioritized by the workshop facilitators was not directly relevant to their chosen profession. One student’s response exemplified this sentiment:

Presenting an educational program that you were planning for 9 h in three minutes with three slides to an audience/jury consisting of designers, innovation advisors, business developers and project managers did not at all give me the feeling of having made a great learning gain for me as a teacher. As most of us become or already are teachers, I do not know whether the tips from a business developer on how to speak in front of a group of people makes any sense or helps anyone. In addition to that, I do not think that organizing the whole presentation as a competition is a nice setting. As it should be much more about collaboration and giving useful feedback and asking critical questions, where there was no time for.(Student Teacher 8)

For many students, the pitch session proved stressful and irrelevant. It lacked emphasis on collaboration and critical feedback related to the educational content. The three-minute pitch method failed to capture the entire thinking process, the dedication, and the nuanced questions. As a result, the students felt the essential aspects were lost during this condensed presentation of conference ideas:

I would have loved it if the final presentation would have been more focused on the actual conference and program we designed and less on how to make it a good pitch (was interesting, but nothing new). How to make a business pitch is not that relevant for us as teachers.(Student Teacher 8)

Students recognized missed opportunities and weaknesses due to time constraints during the Stormathon. They wanted to share and highlight more of their teams’ innovative sustainability ideas, state-of-the-art concepts, and proposals for a successful and unique hybrid conference. These reflections occurred during the final stages of the conference.

5.4. RELATING with Creative Confidence and Values-Thinking Competence for Embodied Engagement Connecting Empathy and Compassion

Embodied engagement emerged through carefully selected future-oriented methods. The students appreciated the interactive layout aspects inherent in the case processes. Collaborating in teams with mixed nationalities, they gained exposure to a rich tapestry of diverse perspectives:

I learned a lot of new things from my team: The ability to be creative and do something different. New methods. Opportunity to get an insight into different fields and areas. Get to know the other students and solving the “case” together.(Student Teacher 7)

Three general competencies were frequently highlighted as crucial for driving sustainability transformations: critical thinking, creativity, and learning (cf. [43]):

The aspect of creativity team-working skills has been promoted—communication, listening to each other, trying to understand the ideas of the others, appreciate/accept the ideas/view of others, the fika [Swedish coffee break] ☺ nice people who tried to support us/our working process. Structure and guidance. Empathy role (teacher, student).(Student Teacher 5)

Although some students appreciated the facilitators’ interpersonal competency [43] for their input and support during the creative working process, others perceived it as a moment of disruption. However, such disruptions are essential for driving transformative and transgressive development in sustainability learning in higher education, as highlighted by Lotz-Sisitka et al. [35]. These disruptions can provide opportunities for engaged, experiential, transformative praxis for student teachers. To build a more sustainable world, we need more disruptive capacity building and transgressive pedagogies [44]. The described forms of learning all require engaged forms of pedagogy that involve impactful stakeholder engagement and collaborative teamwork [43,45]:

Sometimes we were very engrossed in our planning in our team rooms and were in full flow when someone came in and asked us lots of questions or criticized us, and that often threw us off track. That took our motivation away. The thing is that the timing just wasn´t right for it when we were in the middle of discussions. Moreover, it wasn´t about educational stuff but more about the “marketing stuff”… I am sure there was no bad intent behind it; but, unfortunately, in most cases, these multiple disturbances did not help us.(Student Teacher 4)

Self-reflection on the Stormathon, as documented in the TfS student papers (13 January 2023), also showed the challenging nature of climate change for certain participating students. Moreover, it underscored the importance of action-oriented learning activities:

I could never grasp the whole concept and the consequences of it/the collapse of the Earth. I still struggle up to this day to have an optimistic outlook on this situation and to keep the balance between staying informed and not being overwhelmed by all the negative information. The workshops and seminars helped me to keep this balance, because here we learned more about the actual ideas and how we can teach sustainability. Especially the Education for Change workshop and the Stormathon helped me to get a more practical approach on this topic. And besides that provided me with many resources I can use in the future. For me, personally, it was very inspiring to see with what ideas everyone else came up with and to have an open space to share ideas and concepts.(Student Teacher 8)

This exemplifies what Lotz-Sisitka et al. [35] describe as transformative and transgressive forms of social learning—a process that requires co-learning in multi-actor and multi-voiced formations. Concerning whether the students achieved a respectable conference concept for the CEI 2024 case via the processes at the Stormathon (median value of 5 out of 6), the responses highlighted the robust influences of a whole institution approach in the social-ecological transformation (cf. [26,72]. Additionally, the hackathon-inspired ideas and the brainstorming were experienced as productive, as illustrated in the following:

There are many more connections and thoughts that you can make while talking about a topic. I like that I could always refer to what others were saying. Also, it isn’t that exhausting while speaking. I feel like more ideas come “flowing” into your mind because your brain is always searching for new things to say, so it is more like a brain Stormathon, which is very productive.(Student Teacher 6)

The students also highlighted that certain aspects of the CEI 2024 case-solving processes at Stormathon could benefit from change and improvement. Specifically, they expressed a desire to delve deeper into the role of schools in society, embracing a whole-school approach. This exploration would shed light on the significant influence schools wield in driving social-ecological transformation:

I think, for our team, it was important to have a common thread and a framework around our whole program, to include physical activities, nature, and to put a focus on communication and taking actual action and use the possibility to decrease hierarchy between teachers and students and create a global dialogue, since some countries are already much more effected by the climate change than we are.(Student Teacher 7)

In alignment with several of the quotations above, another student teacher (5) also observed that the students had developed a good idea for the concept with a clear framework and a common thread. As also emphasized by Lotz-Sisitka et al. [35], knowledge co-production can be positioned under scientifically new or “post-normal” conditions during such specific pedagogical processes. The emergence of a form of disruptive competence in and for higher education is, therefore, critical and warrants consideration (cf. [6]).

5.5. ACTING Based on Perseverant Professional Knowledge-Driven Change—Bridging Didactics by Connecting Theory-Loaded Empiricism and Empirically Loaded Theory

Professional knowledge emerged from the theory-induced entrepreneurial design thinking [19]. The hackathon produced both negative and positive consequences, particularly relating to subject-didactic modeling (cf. [8]). Student teachers expressed very strong criticism in their evaluations, holistically analyzing the efficiency, the management, and the actual knowledge concept development within the framework of the hackathon ideation process. In several respects, the Stormathon format did not align with the content, intention, acting, and design of the individual participants (cf. [65]. While the workshop format encouraged performativity in acting, invention, and spontaneous shifting collectively, it fell short of achieving the anticipated smooth pathways for catalyzing change, building viable sustainability capital, and delivering appropriate sustainability competencies [43,59]:

I do not think that my learning outcome was big because there were not many opportunities for me to learn something new. For example, there was no inspiring materials or deeper background information on a specific topic that could have been used as a topic for the conference (e.g., fast fashion, water pollution…). That would have been useful to go much deeper in planning an interesting program… And despite that we had a whole day, there was no time to do some own research on topics or new teaching methods. I mean, I learned something about the whole “designer innovative” world, but this made me question if we could ever solve global issues if we spend our time cheering at every idea and nonsense that comes out of our mouths, like we had to. This hinders honest communication. There were so many things in the whole setting that hindered me to learn something. Moreover, I already organized workshops, discussion rounds, etc. on that topic, where I had the feeling that I learned much more and took much more responsibility since these events were happening.(Student Teacher 4)

Such student reflections indicated a need for a “new philosophy” and alternative formats in sustainability didactic modeling for the development of both compassion and critical knowledge capabilities toward sustainability commitment (cf. [49,58,73]). Despite the numerous shortcomings highlighted by many students, constructive aspects of these complex relationships were also evident, and certain advantages were conveyed:

In a specific way, we were actively involved during our Stormathon. During this innovation bootcamp, we had to come up with different workshops and tasks to form a conference cut out for students and teachers. We learned multiple ways of idea generation and were challenged to think and work as innovators rather than teachers. All this showed and emphasized to me the importance of involving the students, activating prior-knowledge, and nurturing their motivation, as well as posing a challenge to them.(Student Teacher 8)

Some students personally experienced the development of an architecture as an educator through the lens of sustainable grown-upness. They recognized this as one of the benefits of working with the concrete case and the performance framework within it:

Before attending the course at Malmö University, my knowledge when it comes to sustainability was limited, which hindered me to talk about it with other people and my parents. If I talked about it, the knowledge wasn’t as profound, which didn’t make me feel confident or too comfortable talking about it. I did have a certain interest and motivation in the topic, which is why I was sad I didn’t learn about it in my home university. This lack of confidence would have resulted in me not teaching it effectively to my students. My guess is that this is also why I didn’t learn about it when I was in school. It was not the biggest topic at the time, and my teachers probably didn’t know much about it themselves. I am so glad that I was enabled to effectively teach sustainability in my future classroom. While I already knew most of the didactics and models I was told about in the course, I would not have been good to use them to teach sustainability. Now, I feel confident to teach sustainability, be a role model to the students and choose the right methods and tasks to do. I was never a person who didn’t care about the environment and a just future, but it was never too strong either, if I have to be honest with myself. Ever since the seminar and knowledge and awareness I gained, I get so much more involved in changing something and taking action. I experienced first hand why teaching for sustainability is such an important topic.(Student Teacher 3)

The long-term implications of the Stormathon are also discussed in the self-reflections in the student papers (n = 8; 13 January 2023). Despite being perceived as demanding, the Stormathon activities were deemed a valuable component of the course. Many student teachers had no prior experience with similar workshops. Consequently, participating student teachers acquired key sustainability planning competencies, including systems-thinking, values-thinking, self-reflection, and teacher competencies [43]. They also learned how to work practically with learning activities to support the attainment of professional key competencies. Furthermore, they systematically assessed the curriculum integration of key competencies while designing a hybrid conference with sustainability in mind.

6. Discussion

In this section, the research design is considered, and the results of the analyses are discussed at an overarching level. Certain conclusions are drawn regarding how these results can serve as a basis for further work with digitization and hybrid knowledge formation with the aim of developing diverse teaching approaches. Courageously, the impact of the critical perspectives on higher-education didactics for sustainability practices in teacher education—with emphasis on student teachers’ experiences of learning affordances of future-oriented methodologies as educational development approach towards sustainability commitment has been shed light on.

From a didactic perspective, the student teachers perceived the case methodology as relevant to teaching and learning for sustainability, with clear links to subject-specific content (sustainability didactics). The selected case allowed them to go beyond traditional boundaries imposed by the curriculum and institutional structures in education. However, this freedom also meant they received less support in developing strategies to work within such constraints. Furthermore, more course input could have been provided on the dilemmas associated with the teaching and learning situation of the CEI 2024 context.

The method employed in this study also acknowledges the strengths of using collaborative design thinking in higher education to foster subjectification and create a sense of community [19,74]. As the student teachers engaged in this process, they developed critical sustainability knowledge capabilities grounded in involvement and empowerment (cf. [49,50]).

Applying the concept of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in education goes beyond merely introducing curriculum content about sustainability. It also involves working with contemporary innovative approaches to pedagogy [4] and designing courses that encourage a deep approach to learning [75]. By recognizing IDGs integrated with SDGs and providing sufficient opportunities for reflection on concrete cases, learners can be committed with powerful sustainability insights and capabilities—enabling them to act as responsible global citizens [27]. Additionally, the value of informal learning opportunities is also prominent in the findings. The anchoring of the IDGs within the SDGs develops a framework for the proposed hybrid conference and can offer beneficial non-formal learning affordances, especially when collaboratively designed with innovative teacher education at university level [26,71]. While there are benefits to challenging tasks and pushing learners beyond their “comfort zone”, even in higher education [76], a shared vision of the activity and clear alignment in aims and expectations are necessary to retain participants’ confidence in the process [6,65].

In this study, many student teachers expressed that support and direction were lacking during the Stormathon activities. They felt compelled to opt for a “quick fix” rather than taking the time to address the dilemmas and learn from the phenomenon presented by the case. The students were tasked with addressing the topic of sustainability in the presentation of an agenda for the hybrid conference CEI 2024, which aligns with Agenda 2030 and the SDGs. However, some students experienced that their planning toward this goal did not gain adequate recognition. In their opinion, the didactic aspect was limited, and their planning of the case, prior to pitching it, was disregarded. Rather than being allowed to present the best conceivable activities for a full-day program during the CEI 2024 hybrid conference week (cf. [77]), the Stormathon format required them to reorganize their work and focus instead on managing what some deemed a high-profile pitch competition. This could be compared to Kahneman ([78]), who portrays intuition as recognition, which the more experienced teacher demonstrates by immediately accessing the answer stored in memory and good intuitive judgments arise. This contributes to the influence of decision-making in new situations, enabling a more experienced teacher to act appropriately. However, the spontaneous search for an intuitive solution can sometimes fail; in such cases as with student teachers, a shift may occur in the mindset towards a slower, more deliberate, and effortful form of thinking. But, the students were solution-oriented and wanted to independently direct the design process. However, they experienced that the time allotted was insufficient to fully consider the different constructed dilemmas presented by the Stormathon. As a result, they were unable to identify or conceive the didactic tools required for a continued learning progression and the context-based teaching of the case.

With increasing complexity comes greater uncertainty among students. And different approaches to modeling for sustainability necessitate translation across various contexts. Against this background, lecturers should actively participate in the conception or the revision of study programs providing guidance for sustainability to scholars and educators to understand the IDG concept and emergent field of inner transformation better, along with its main contribution supporting individual, collective, and system change [42]. Furthermore, the competency structure should be coordinated and harmonized across the modules and the educational elements—such as courses, excursions, projects, and assessment of learning outcomes contained therein. This ensures a common understanding of the competency structure across the entire study program among the lecturer team. When designing the various educational elements, clear communication with the students is crucial regarding the contribution of each educational component, teaching/learning arrangements, and assessments in achieving the desired competency development across the individual educational elements.

Students participating in the Stormathon workshop learned through their experiences and reflection that the pedagogy within design thinking needs to be more explicitly highlighted (cf. [19,79]. For many of the student teachers in this study, merely modeling good practice in general terms was insufficient to bridge the gap between the Stormathon assignments, which they perceived as fragmented or irrelevant, and the actual pedagogical practices to be implemented for the hybrid CEI 2024 conference program. Due to the limitations and shortcomings experienced on how individual, collective, and system change are entangled, it is important to shed light on why sustainability challenges can be understood as crises of relationships, disruptions, or disconnection and how—by shifting focus from entities to relationships, their qualities, and the processes comprising these. Modeling via HEDS can improve current approaches [42]. The analysis of the discussions of challenges recognized in the workshop [15] and the processes, in terms of communication, coordination, and cooperation, show conflicting feelings among the workshop facilitators and a sense of despair among some students. Nevertheless, for educators intending to redesign curricula in higher education from “a responsible research and innovation perspective”, enriching tools are recognized and accessible [7]. Based on a whole institution approach [25], the IMAGINE model presented (Figure 4) could be a useful instrument for heading a system change in the TfS course moment described in this study.

The student teachers expressed concerns regarding mutuality and conceptual clarity, differences in enabling critical reflections, and the process of turning theory-influenced learning processes into improved practice. Although the Stormathon intended to provide a valuable (cf. [19]) area for learning by exploring critical knowledge capabilities [4] through using design thinking, many students found the knowledge formation process unsatisfactory. They considered the subject didactics theory-based professional support [37] to be insufficient (cf. [80]). The students reported that the powerful sustainability insights were not sufficiently explained, and the main motivation for undertaking their case was lacking. They were deeply committed to finding mutually beneficial solutions [16] (Calvo to meet the goal of the challenge presented at Stormathon. This involved focusing on disrupting deep-rooted normative learning and teaching patterns, promoting eco-reflexive thinking, and capturing sustainability learning affordances. As Calvo, Cruickshank, and Sclater [16] point out, this underscores the need for more research to deepen our understanding of mutually transformative learning and co-design.

7. Conclusions

This study examined some of the challenges associated with integrating didactic models and design thinking for educational development in the field of teaching and learning for sustainability [19]. It contributes to wider research on the integration of digital tools into the curriculum in upper-secondary schools, teacher education, and tertiary contexts (cf. Figure 1). Exploring the role of technology-enhanced learning, including AR and VR [10,22], both the potentials and obstacles in enhancing authenticity and engagement in eXtended reality ([81]) are highlighted. This is achieved through student-developed hybridity, which enhances the contextualization of ongoing realities [11,32].

The methods employed at Stormathon hold the potential for long-term utility in the professional roles of future student teachers [51,57]. However, certain key features required by future-oriented methodologies [82], such as creativity and collaborative boundary-crossing explorative approaches, could either support or impede the development and innovation of these methodologies. In this context, the student-teacher reflections about CEI 2024 will be invaluable. They will be utilized by the executive committee in the Swedish branch of CEI in planning future conferences. These reflections serve an advisory role, offering insights on how to further optimize educational development. This includes how higher-education teachers can collaborate within student-teacher training courses and in planning to participate in the workshops at the Stormathon Innovation Hub. Finally, the perspectives of the student teachers are also crucial for the research field in general.

The present study, based on student evaluations and reflections, contributes a crucial perspective to the developing approaches in sustainability didactics. The aim of the study was to analyze student perspectives rather than to evaluate learning outcomes in terms of sustainability-related competencies. Hammer and Lewis [83] employed a scaled self-assessment method in their research, concluding that more innovative tools for planning competencies are needed to go beyond self-assessment. From this perspective, there is a call for more studies that explore how to propel research and progress in future-oriented methodologies and higher-education didactics toward sustainability.

8. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

This study is among the first to examine the impacts of combining transformative learning and design theory as a pedagogy in higher-education didactics for sustainability (HEDS) with an exploratory approach. This has implications for the study, which has quite a few limitations. Hence, methodological considerations will be shed light on in this section. However, that also leaves lots of space for future research within the field of HEDS and connections to inner transitions and dimensions of how sustainability education intervention affects learners differently and under different conditions.

Credibility is established by obtaining significant data that allow for posing adequate questions, conducting systematic connections throughout the research process, and crafting an ample analysis. The number of participants could be argued to be low. Therefore, the descriptive statistics claims made might not be considered to verify the result because of the small sample size. Still, the sample size was good for qualitative data, even though the validity was less reliable, referred to a quantitative approach. Brinkmann and Kvale ([84]) recommend that around 15–20 participants are optimal for conducting an in-depth analysis of data. This is often sufficient for a qualitative study that is relatively limited in scope. Considering this, in combination with the principle of saturation that underpins the methodological approach, the 18 participants and the interview-like questionnaires with open-ended questions and the essays provided sufficient data together with the observations notified. Another potential weakness is the gender predominance of female informants. However, there was no opportunity to include more male students since the majority of the course participants were female students. Despite this gender imbalance, the data were deemed sufficient, and the results contribute new insights. Therefore, without claiming that the results are representative of all student teachers and for all purposes, they are transferable, as generalizations are made through recognized categories of descriptions rather than by numerical representation. The answer frequency (also concerning the quantitative data) indicates that most of the voluntarily participating informants were relatively satisfied with sharing their reflections and experiences of applying the future-oriented methodologies and seemed to be genuinely eager to do so.

The rationale behind prioritizing student feedback in the study originates from a need for an in-depth understanding of possible processes and to explain methods linking specific learning activities and didactics with different phases of the student-teacher’s learning process (cf. [49]). Student teachers must additionally identify the conditional contexts in which HEDS works best to construct targeted confirmed outcomes. Educational efforts (i.e., teachers’ moves in relation to students’ sustainability commitment) might affect students differently under various conditions. Questions critical to answer are: First, if and how a newly gained mindset, skillset, and creative confidence, i.e., new learnings translate well into actions and benefit students’ individual well-being. Second, what factors explain why graduates from the same group perform differently during the course? Finally, the potential cognitive, emotional, practical, social, or organizational impacts should also be considered.

Potential biases explored might be in the framework of describing how various key sustainability competencies recognized and design theory-influenced pedagogical components are working in concert to support the development of redesigning higher-education didactics for sustainability. Due to eventual gaps in the approach of this study, future research may consider examining the longer-term impacts of HEDS on multiple levels of analysis. With longitudinal approaches and a longer time frame, career development can be followed and evaluated after the end of the teacher education program. That is missing in the current study due to time limits.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical guidelines of Swedish Research Council were followed during the research study and writing of this manuscript. This study was not subject to ethical review since no sensitive personal data were emerged.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Both orally during group forum discussions (witnessed by all the students, i.e., the informants several different times in the class and during the various workshops) and in connection to Questionnaires from which data were gathered. During the study, ethical guidelines stated by the Swedish Research Council (2017), have been thoroughly considered and applied. In this study, anonymity has been achieved in the transcriptions (Swedish Research Council, 2017). Data are stored and processed accordingly ((Swedish National Data Service, 2021. Checklist for Data Management Plan (pp. 1–16). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6424769). No sensitive personal data were gathered in this study (Swedish ResearchCouncil, 2017. Good research practice, Report no. VR1710, https://www.vr.se/english/analysis/reports/our-reports/2017-08-31-goodresearch-practice.html, accessed on 25 May 2024).

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to ethical restrictions. The data presented in this study can be available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Studies in Science, Environmental and Mathematics Education (SISEME) for research funding (autumn 2022) from the Department of Natural Science-Mathematics-Society at the Faculty of Education and Society, Malmö University.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Framework for the Implementation of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Strategy for Education for Sustainable Development from 2021 to 2030. ECE/CEP/AC.13/2022/3. 2022. Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2022-05/ece_cep_ac.13_2022_3_e.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Dixson-Decleve, S.; Gaffney, O.; Ghosh, J.; Randers, J.; Rockstrom, J.; Stoknes, P.E. Earth for All: A Survival Guide for Humanity; New Society Publishers: Gabriola, BC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson, E. Programme to Boost Young People’s Environmental Engagement. Web News at Malmö University. 5 April 2024. Available online: https://staff.mau.se/first-page/staff-news/programme-to-boost-young-peoples-environmental-engagement/ (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Nordén, B. Learning and Teaching Sustainable Development in Global-Local Contexts. Doctoral Dissertation, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Government Offices of Sweden. Goal 4: Quality Education. 2015. Available online: https://www.government.se/government-policy/the-global-goals-and-the-2030-Agenda-for-sustainable-development/goal-4-gender-equality/ (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- Mochizuki, Y.; Yarime, M. Education for sustainable development and sustainability science: Re-purposing higher education and research. In Routledge Handbook of Higher Education for Sustainable Development; Barth, M., Michelsen, G., Rieckmann, M., Thomas, I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tassone, V.; Eppink, H. The EnRRICH Tool for Educators: (Re-)Designing Curricula in Higher Education from a “Responsible Research and Innovation” Perspective. Deliverable 2.3 from the EnRRICH Project. 2016. [Google Scholar]