Unlocking the Transformative Potential of Outdoor Office Work—A Constructivist Grounded Theory Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Previous Research

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Selection

3.2. Interviews

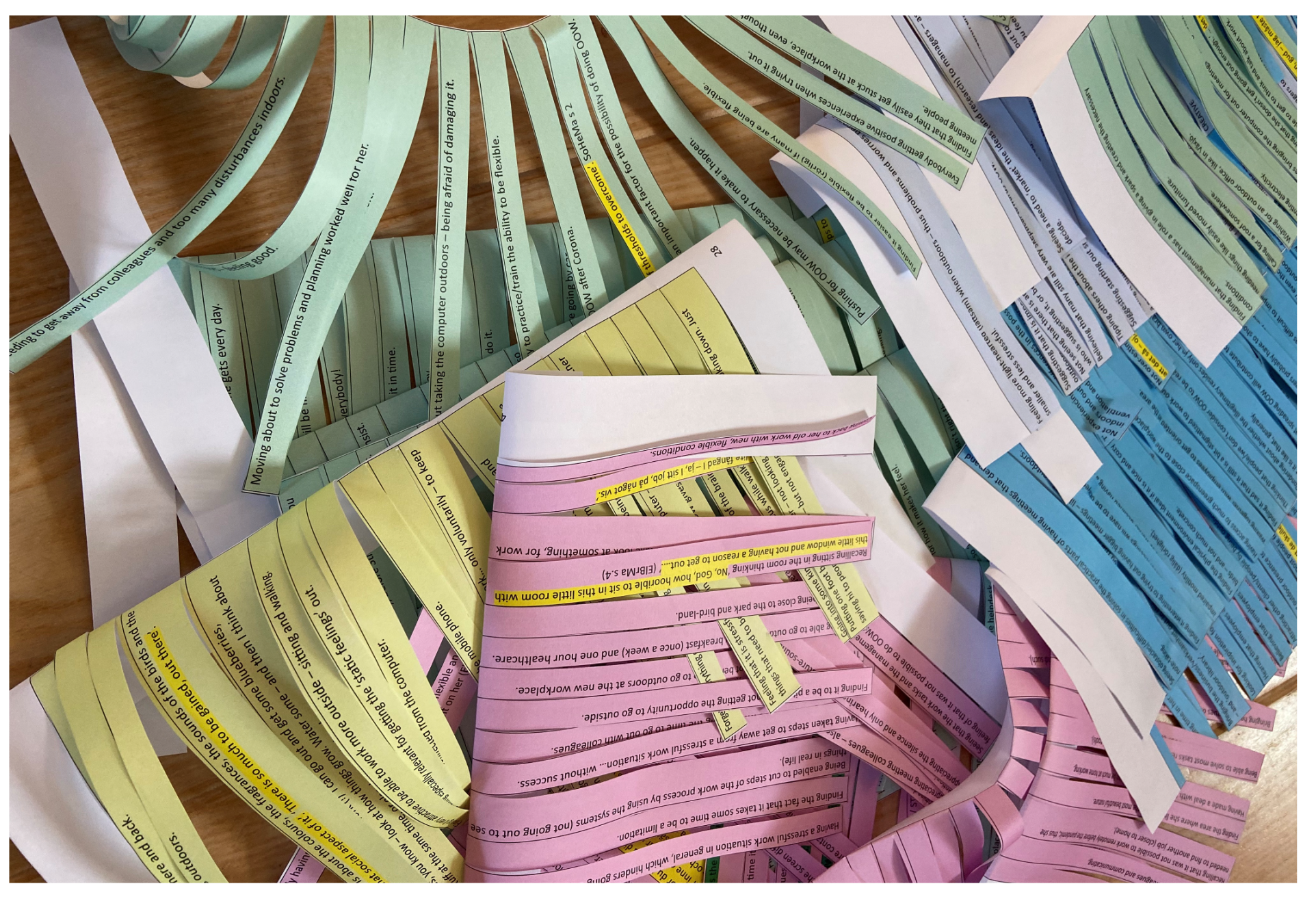

3.3. The Coding Process

3.4. Ethical Statement

4. Results

4.1. Practicing Outdoor Office Work

“When you start thinking about this, it’s like—why haven’t we done this before—it seems really strange. If you think about it, if you’re reasonably intelligent, all the health benefits of being outside, getting fresh air, sunlight, greenery…”(C)

“Think outside the box—that it will work. (…) put on a pair of comfortable shoes, and begin with walking meetings, I mean (…) don’t make it such a big deal that you have to sit in a specific place and be on screen all the time, and many people turn off their screens anyway, so you too can do that.”(C)

4.2. Challenging the Taken-for-Granted

“It is more like—“Wow, what a luxury. You look like you’re having a wonderful time!” But, I choose not to interpret it as—“Aha, here you are, basking in the sun” (…) but, absolutely—some probably have these thoughts and don’t find it as quite as much work, to sit outdoors.”(O)

“There is something telling me—and I think that many would agree—that it isn’t really work when you’re outside working. Somehow there is still this—and maybe that’s just me, because I haven’t heard anyone saying it, so maybe it’s just in my head, but generally I think that there is a view that one should sit at the office in front of the computer.”(K)

“It feels a bit like—you know—when you’re sitting indoors in cozy clothes (…) That it’s a bit casual in a way. With all this in the background, when there’s a breeze or the sun is shining so wonderfully, it makes me come across as if I’m not taking the meeting seriously enough, like I’m just slacking off a bit.”(H)

“… if you are the only one stepping out, all the time, that will probably make one feel like they’re sort of sneaking away from work, but (…) if you see that the boss does it, then it’s kind of a completely different thing.”(O)

“The opportunities are there, and I do it sometimes. I just go out the door and I walk in the neighborhood of the head office, but the work life has changed since the pandemic in a way (…) we work fifty percent at home and fifty percent at the office, in my team. So, the fifty percent at the office, is also consciously and unconsciously chosen to be at the office, because we want to be together. So, if I then say—hey, I walk—then I don’t live up to this new rule of being together.”(A)

4.3. Enjoying Freedom and Disconnection

“And, also when you are outside, you are distant from the physical work—the frame of the physical work—the building and everything that is associated with that. When you leave that space you go into another space, where I feel you are a little distant from that. That might also be why you feel a bigger belonging because you are not constrained (…) So, when you are in a physical building your whole system is filled up with everything you have experienced in that building. For instance, with these people in these meeting rooms. When you’re outside, you are out of that. So, you are more free.”(D)

“There is something about not sitting in front of each other. When you are walking next to each other, then someone is coming up to you and then suddenly it is a new group talking and then behind yourself… so you are much more social and more diverse and more equal, I would say.”(D)

4.4. Feeling Connected and Interdependent

“Now, I look in front of me and I am seeing trees, trees, trees (…). So, in the parallel part of your system… that’s just how it is for me—and then I feel… I get this humbleness. Being part of this bigger thing.”(D)

“Also, that’s where the unpredictable aspect comes in. There’s something about it. The unpredictability might be unwelcome in more formal meetings, but in more informal ones, it can be an advantage because then it becomes more relaxed… a cat comes running by, or it could still happen indoors, but I don’t know—things happen, you know, that weren’t always planned, and it’s just a bit more lively.”(E)

“While, if I get to walk (…) I don’t do twelve other things at the same time, so I listen—I mean, I listen hundred times better when I am outdoors having this meeting, because then it is just that.”(A)

4.5. Promoting Health and Well-Being

“It feels (…) much better that work in a way is connected to your health (…) it means really a lot that you have felt that it is very connected to a healthier lifestyle that I get at work instead of having to take care of it outside of work, exclusively.”(O)

“Yeah, if you manage to combine this (working outdoors), then you have the peace after work, otherwise when you come home from work—no, now I have to go out, or get that part that’s needed. Everyone needs to get out a bit, but then I’ve already had my exercise and I’ve already had my fresh air, so I don’t need to rush out in the evening, so then I also have the peace to be at home and cook dinner and do whatever needs to be done. I get a completely different balance in my schedule throughout the day.”(L)

“… I suppose that it’s both physical and psychological […] and that is of course interrelated, but […] I often find that it comes at the end of the day—I have a feeling in my body telling me ‘how was this day?’—and, the more I have been moving about, been outdoors, seen different things—have had a kind of connection with something real—nature, or trees, or—you know—outdoors, with everything that is. Then, I can get this nice feeling. If it has been sunny and such—it can remain for a long time […] it is a good feeling in the body. I feel that I have gotten sun. It may have been a little windy, but still it feels good, because—yeah, I feel more alive at the end of a day like that.”(E)

4.6. Enhancing Performance

“In one way it is more efficient, because you are solving your problems on site and that’s much more telling than sitting indoors looking at a map. You sense the place in a different way. And, in that way it is more efficient to be outdoors—as you may get a quicker solution.”(I)

“… but, I can’t say that it is so—oh, it is so much more efficient! But, in one way I would like to say that I feel that many meetings can be shortened (…) and in those walk-and-talks—I think that they are improving, in terms of quality, because we listen, so it feels as if we—so, we are much sharper when outdoors—walking and talking. They become more, I was about to say clinical, but I meant ‘clean’ (…) it is easier to stick to the subject. I also feel another thing being about memory-training, or to actually not needing to have everything on a Power Point, or a screen (…) that it’s easier to—yes, that’s right—this is what we are supposed to talk about.”(C)

“I feel creative when I walk here and look at the rowan-berries, the leaves, the yellow flowers—and I am thinking that—Wow, something really happens with my head when I get impressions like that. Then, I also think that there is something about the feet moving. I don’t know what it is, but I feel as if it helps one’s thoughts—that you get a certain pace in your flow of thoughts.”(A)

4.7. Adding a Dimension

“Otherwise, when you’re just sitting and working, it’s just that you get out of what you’re doing. That is, if I’m sitting and doing something, that’s just it—there’s nothing beyond that. But, if I’m sitting outside, it’s like this: Yes, then it’s what I accomplish, plus I get a bit of sun or whatever it may be, or just a bit of wind on my face […] If I have just been sitting indoors, in a dark room—among a bunch of folders and such—it can feel very… I don’t know—just very… It is hard to describe the feeling in your body. It is more a kind of nothing.”(E)

4.8. Framing the Findings

5. Discussion

5.1. Developing Healthier and Smarter Ways of Working

5.2. Transforming Work Life

5.3. Methodological Considerations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal8#targets_and_indicators (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Duran, A.T.; Friel, C.P.; Serafini, M.A.; Ensari, I.; Cheung, Y.K.; Diaz, K.M. Breaking Up Prolonged Sitting to Improve Cardiometabolic Risk: Dose-Response Analysis of a Randomized Cross-Over Trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2023, 55, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenfors, C.U.; Magnusson Hanson, L.; Oxenstierna, G.; Theorell, T.; Nilsson, L.G. Psychosocial working conditions and cognitive complaints among Swedish employees. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Osberg, G.; Osika, W.; Herndersson, H.; Mundaca, L. Linking internal and external transformation for sustainability and climate action: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, M.P.; Izak, M. Paradigms of Flexibility: A Systematic Review of Research on Workplace Flexibility. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2021, 18, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, J. Remote working: Unprecedented increase and a developing research agenda. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2022, 25, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Klerk, J.J.; Joubert, M.; Mosca, H.F. Is working from home the new workplace panacea? Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for the future world of work. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2021, 47, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lid Falkman, L.; Palm, K.; Rosengren, C. Kontoren som kan ändra vårt sätt att leva: Tre trender formar framtidens hybrida kontor. Forte Mag. 2023, 11, 26–27. Available online: https://forte.se/app/uploads/2023/11/fort-0095-forte-mag-nov-2023-ta.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Margolies, J. The Next Frontier in Office Space? The Outdoors. The New York Times, 15 January 2019. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/15/business/office-buildings-nature-biophilia.html (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2014; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, M. How might contact with nature promote human health? Promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 141022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Grellier, J.; Wheeler, B.W.; Hartig, T.; Warber, S.L.; Bone, A.; Depledge, M.H.; Fleming, L.E. Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Hartig, T.; Martin, L.; Pahl, S.; van den Berg, A.E.; Wells, N.M.; Costongs, C.; Dzhambov, A.M.; Elliott, L.R.; Godfrey, A.; et al. Nature-based biopsychosocial resilience: An integrative theoretical framework for research on nature and health. Environ. Int. 2023, 181, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.G.; Craig, T. The great outdoors? Exploring the mental health benefits of natural environments. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, E.A.; Estes, D. The effect of contact with natural environments on positive and negative affect: A meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Anderson, C.B.; Berman, M.G.; Cochran, B.; de Vries, S.; Flanders, J.; Folke, C.; Frumkin, H.; Gross, J.J.; Hartig, T.; et al. Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenfors, C.U.D.; Van Hedger, S.C.; Schertz, K.E.; Meyer, F.A.C.; Smith, K.E.L.; Norman, G.J.; Bourrier, S.C.; Enns, J.T.; Kardan, O.; Jonides, J.; et al. Positive Effects of Nature on Cognitive Performance Across Multiple Experiments: Test Order but Not Affect Modulates the Cognitive Effects. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R. View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1983; pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Atchley, R.A.; Strayer, D.L.; Atchley, P. Creativity in the Wild: Improving Creative Reasoning through Immersion in Natural Settings. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.J.H.; Lee, K.E.; Hartig, T.; Sargent, L.D.; Williams, N.S.G.; Johnson, K.A. Conceptualising creativity benefits of nature experience: Attention restoration and mind wandering as complementary processes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 59, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.; Barnes, M.; Jordan, C. Do Experiences with Nature Promote Learning? Converging Evidence of a Cause-and-Effect Relationship [Mini Review]. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 423551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.; Jordan, C. Editorial: The Natural World as a Resource for Learning and Development: From Schoolyards to Wilderness. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 475561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, K.H.; Raanaas, R.K.; Hägerhäll, C.M.; Johansson, M.; Patil, G.G. Nature in the office: An environmental assessment study. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2017, 34, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Largo-Wight, E.; Chen, W.W.; Dodd, V.; Weiler, R. Healthy workplaces: The effects of nature contact at work on employee stress and health. Public Health Rep. 2011, 126 (Suppl. S1), 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnstad, S.; Patil, G.G.; Raanaas, R.K. Nature contact and organizational support during office working hours: Benefits relating to stress reduction, subjective health complaints, and sick leave. Work 2016, 53, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dravigne, A.; Waliczek, T.M.; Lineberger, R.D.; Zajicek, J.M. The Effect of Live Plants and Window Views of Green Spaces on Employee Perceptions of Job Satisfaction. HortSci. Horts 2008, 43, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, X.; Jiali, L.; Jiang, B. Creating Restorative Nearby Green Spaces for Knowledge Workers: Theoretical Mechanisms, Site Evaluation Criteria, and Design Guidelines. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2022, 10, 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lottrup, L.; Stigsdotter, U.; Meilby, H.; Claudi Jensen, A.G. The Workplace Window View: A Determinant of Office Workers’ Work Ability and Job Satisfaction. Landsc. Res. 2013, 40, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Rodríguez, M.L.; Testa Moreno, M.; Moreno-Jiménez, P. Nature in the Office: A Systematic Review of Nature Elements and Their Effects on Worker Stress Response. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. The role of nature in the context of the workplace. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1993, 26, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lygum, V.L.; Dupret, K.; Bentsen, P.; Djernis, D.; Grangaard, S.; Ladegaard, Y.; Troije, C.P. Greenspace as Workplace: Benefits, Challenges and Essentialities in the Physical Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, C.; de la Fuente Suárez, L.A.; Tillander, A.; Toivanen, S.; Bälter, K. The outdoor office: A pilot study of environmental qualities, experiences of office workers, and work-related well-being. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1214338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersson Troije, C.; Lisberg Jensen, E.; Stenfors, C.; Bodin Danielsson, C.; Hoff, E.; Mårtensson, F.; Toivanen, S. Outdoor Office Work—An Interactive Research Project Showing the Way Out. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 636091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plambech, T.; Van Den Bosch, C.C.K. The impact of nature on creativity–A study among Danish creative professionals. Urban For. Urban Green 2015, 14, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudokas, K.; Dogan, H.A.; Viliūnienė, O.; Vitkuvienė, J.; Gražulevičiūtė-Vileniškė, I. Office-nature integration trends and forest-office concept FO-AM. Archit. Urban Plan. 2020, 16, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javan Abraham, F.; Andreasson, P.; King, A.; Bälter, K.; Toivanen, S. Introducing outdoor office work to reduce stress among office workers in Sweden. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33 (Suppl. S2), ii535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M.; Mårtensson, F.; Vogel, N. Developing outdoor spaces for work and study—An explorative place-making process. Front. Sustain. Cities 2024, 6, 1308637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herneoja, A.; Rönkkö, E.; Haapakangas, A.; Malve-Ahlroth, S.; Oikarinen, E.; Hosio, S. Interdisciplinary approach to defining outdoor places of knowledge work: Quantified photo analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1237069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaz, K.; Thornberg, R. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, T.M. Grounded Theory Research and Theory Building. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2002, 4, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bladt, M.; Aagaard Nielsen, K. Free space in the processes of action research. Action Res. 2013, 11, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, H. Resonance: A Sociology of our Relationship to the World. Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Damianakis, T.; Woodford, M.R. Qualitative research with small connected communities: Generating new knowledge while upholding research ethics. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapley, E.; O’Keeffe, S.; Midgley, N. Developing typologies in qualitative research: The use of ideal-type analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2022, 21, 16094069221100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, K. Health and Caring—From a European perspective. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2011, 6, 11458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barker, P.; Buchanan-Barker, P. The tidal model of mental health recovery and reclamation: Application in acute care settings. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 31, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCauley, C.O.; McKenna, H.P.; Keeney, S.; McLaughlin, D.F. Concept analysis of recovery in mental illness in young adulthood. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 22, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, K.; Brown, C.; Montarzino, A. Understanding Knowledge Workers’ Interactions with Workplace Greenspace:Open Space Use and Restoration Experiences at Urban-Fringe Business Sites. Environ. Behav. 2017, 49, 314–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, D.; Sherratt, F.; Smith, S. Handling the Hawthorne Effect: The challenges surrounding a participant observer. Rev. Soc. Stud. 2014, 1, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J. Crafting a Job: Revisioning Employees as Active Crafters of Their Work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, C.; Schippers, M.C.; Stegmann, S.; Bakker, A.B.; van Baalen, P.J.; Proper, K.I. Fostering Flexibility in the New World of Work: A Model of Time-Spatial Job Crafting. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, C. Double Loop Learning in Organizations. Harvard Business Review, September–October 1977. Available online: https://hbr.org/1977/09/double-loop-learning-in-organizations (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Mezirow, J. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series; Jossey-Bass Inc Pub: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Polletta, F. ”Free Spaces” in Collective Action. Theory Soc. 1999, 28, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagaard Nielsen, K.; Nielsen, B.S. Critical Utopian Action Research—The Potentials of Action Research in the Democratisation of Society. In Commons, Sustainability and Democratization; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Egmose, J.; Gleerup, J.; Nielsen, B.S. Critical Utopian Action Research: Methodological Inspiration for Democratization? Int. Rev. Qual. Res. 2020, 13, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, E. The Fear of Freedom; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, H. The idea of resonance as a sociological concept. Glob. Dialogue 2018, 8, 41–44. Available online: https://globaldialogue.isa-sociology.org/articles/the-idea-of-resonance-as-a-sociological-concept (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Brinkmann, S.; Kvale, S. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd ed; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. The power of Constructivist Grounded Theory for critical inquiry. Qual. Inq. 2017, 23, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, L. Det vårdande samtalet [The Caring Conversation]. Ph.D. Thesis, Åbo Academy University, Turku, Finland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petersson Troije, C.; Lisberg Jensen, E.; Redmalm, D.; Wiklund Gustin, L. Unlocking the Transformative Potential of Outdoor Office Work—A Constructivist Grounded Theory Study. Challenges 2024, 15, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe15020025

Petersson Troije C, Lisberg Jensen E, Redmalm D, Wiklund Gustin L. Unlocking the Transformative Potential of Outdoor Office Work—A Constructivist Grounded Theory Study. Challenges. 2024; 15(2):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe15020025

Chicago/Turabian StylePetersson Troije, Charlotte, Ebba Lisberg Jensen, David Redmalm, and Lena Wiklund Gustin. 2024. "Unlocking the Transformative Potential of Outdoor Office Work—A Constructivist Grounded Theory Study" Challenges 15, no. 2: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe15020025

APA StylePetersson Troije, C., Lisberg Jensen, E., Redmalm, D., & Wiklund Gustin, L. (2024). Unlocking the Transformative Potential of Outdoor Office Work—A Constructivist Grounded Theory Study. Challenges, 15(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe15020025