Investigating the Impact of Psychological Contract Violation on Survivors’ Turnover Intention under the Downsizing Context: A Moderated Mediation Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

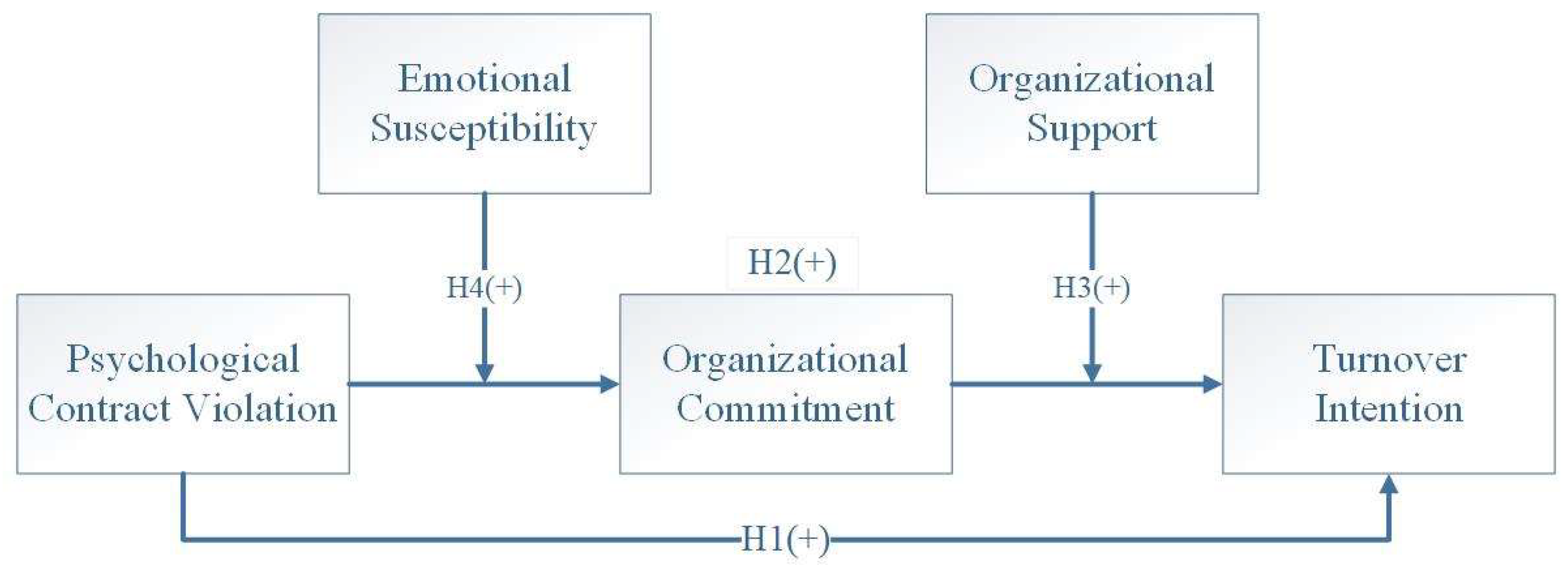

2. Theoretical Basis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Psychological Contract Violation and Turnover Intention

2.2. The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment

2.3. The Moderating Role of Organizational Support

2.4. The Moderating Role of Emotional Susceptibility

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Results

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clinton, M.E.; Guest, D.E. Psychological Contract Breach and Voluntary Turnover: Testing a Multiple Mediation Model. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykan, E. Effects of Perceived Psychological Contract Breach on Turnover Intention: Intermediary Role of Loneliness Perception of Employees. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnley, W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Re-Examining the Effects of Psychological Contract Violations: Unmet Expectations and Job Dissatisfaction as Mediators. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L. Trust and Breach of the Psychological Contract. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 574–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wayne, S.J.; Glibkowski, B.C.; Bravo, J. The Impact of Psychological Contract Breach on Work-Related Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 647–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, M.; Boon, C. Performance and Turnover Intentions: A Social Exchange Perspective. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, A.W.; Der Velde, E.G.V.; Feij, J.A.; Van Gastel, J.H.M. Young Adults in Their First Job: The Role of Organizational Factors in Determining Job Satisfaction and Turnover. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 1992, 4, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosadeghrad, A.M. Occupational Stress and Turnover Intention: Implications for Nursing Management. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2013, 1, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, I.A.; Yadav, A.; Afzal, F.; Shah, S.M.Z.A.; Junaid, D.; Azam, S.; Jonkman, M.; De Boer, F.; Ahammad, R.; Shanmugam, B. Factors Affecting Staff Turnover of Young Academics: Job Embeddedness and Creative Work Performance in Higher Academic Institutions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascio, W.F. Downsizing: What Do We Know? What Have We Learned? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1993, 7, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevor, C.O.; Nyberg, A.J. Keeping Your Headcount When All about You Are Losing Theirs: Downsizing, Voluntary Turnover Rates, and the Moderating Role of HR Practices. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M.; Tetrick, L.E. The Psychological Contract as an Explanatory Framework in the Employment Relationship. Trends Organ. Behav. 1994, 1, 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kutaula, S.; Gillani, A.; Budhwar, P.S. An Analysis of Employment Relationships in Asia Using Psychological Contract Theory: A Review and Research Agenda. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gao, F. Psychological Contract and Turnover Intention: The Mediating Role of Organizational Commitment. J. Hum. Resour. Sustain. Stud. 2017, 5, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Fasolo, P.; Davis-LaMastro, V. Perceived Organizational Support and Employee Diligence, Commitment, and Innovation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.M.; Pereira Costa, S.; Doden, W.; Chang, C. Psychological Contracts: Past, Present, and Future. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2019, 6, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suazo, M.M.; Stone-Romero, E.F. Implications of Psychological Contract Breach: A Perceived Organizational Support Perspective. J. Manag. Psychol. 2011, 26, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Cinanni, V.; D’Imperio, G.; Passerini, S.; Renzi, P.; Travaglia, G. Indicators of Impulsive Aggression: Present Status of Research on Irritability and Emotional Susceptibility Scales. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1985, 6, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L.; Kraatz, M.S.; Rousseau, D.M. Changing Obligations and the Psychological Contract: A Longitudinal Study. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W.; Robinson, S.L. When Employees Feel Betrayed: A Model of How Psychological Contract Violation Develops. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 226–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.; Agrawal, R.K. Shri Ram Centre for Industrial Relations and Human Resources Emerging Employment Relationships: Issues & in Psychological Contract. Indian J. Ind. Relat. 2010, 45, 381–395. [Google Scholar]

- John, P.; Meyer Natalie, J.A. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 108–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nei, D.; Snyder, L.A.; Litwiller, B.J. Promoting Retention of Nurses: A Meta-Analytic Examination of Causes of Nurse Turnover. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starnes, B.J. An Analysis of Psychological Contracts in Voluntarism and the Influences of Trust, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment; Montgomery University: Auburn, AL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, G.A.; Won, D.; Chiu, W. Psychological Contract, Job Satisfaction, Commitment, and Turnover Intention: Exploring the Moderating Role of Psychological Contract Breach in National Collegiate Athletic Association Coaches. Int. J. Sport. Sci. Coach. 2019, 14, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands-Resources Theory. Wellbeing 2014, III, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Grover, S.; Reed, T.F.; Dewitt, R.L. Layoffs, Job Insecurity, And Survivors’ Work Effort: Evidence of An Inverted-U Relationship. Acad. Manag. J. 1992, 35, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.B. Economic Crisis, Downsizing and “Layoff Survivor’s Syndrome”. J. Contemp. Asia 2003, 33, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrando, C.; Constantinides, E. Emotional Contagion: A Brief Overview and Future Directions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 712606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.L.; Morrison, E.W. The Development of Psychological Contract Breach and Violation: A Longitudinal Study. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Wall, T. New Work Attitude Measures of Trust, Organizational Commitment and Personal Need Non-fulfilment. J. Occup. Psychol. 1980, 53, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, W.H.; Horner, S.O.; Hollingsworth, A.T. An Evaluation of Precursors of Hospital Employee Turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 1978, 63, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, R.W. The Emotional Contangion Scale: A Measure of Individual Differences. J. Nonverbal Behav. 1997, 21, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.A.; Chen, L.; Wu, L. Your Care Mitigates My Ego Depletion: Why and When Perfectionists Show Incivility Toward Coworkers. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 746205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghouri, M.W.A.; Tong, L.; Hussain, M.A. Does Online Ratings Matter? An Integrated Framework to Explain Gratifications Needed for Continuance Shopping Intention in Pakistan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Samin, T.; Gulzar, M.A.; Aljuaid, H.; Ahmad, M.; Mazzara, M. User Acceptance of HUMP-Model: The Role of E-Mavenism and Polychronicity. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 174972–174985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Hu, L. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Zhonglin, W.; Lei, C.; Kit-Tai, H. Mediated Moderator and Moderated Mediator. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2006, 38, 448–452. [Google Scholar]

- Bull Schaefer, R.A.; Palanski, M.E. Emotional Contagion at Work: An In-Class Experiential Activity. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 38, 533–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, W.; Zhao, J.; Rust, K.G. A Sociocognitive Interpretation of Organizational Downsizing. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, A.E.; Simmering, M.J. Understanding Pay Plan Acceptance: The Role of Distributive Justice Theory. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2002, 12, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Description | X2/df | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-factor model | PC + OC + TI + OS + ES | 4.20 | 0.126 | 0.153 | 0.425 | 0.392 |

| Two-factor model | PC + OC + TI + OS; ES | 4.03 | 0.123 | 0.168 | 0.444 | 0.425 |

| Three-factor model | PC + OC + TI; OS; ES | 3.98 | 0.122 | 0.167 | 0.455 | 0.434 |

| Four-factor model | PC + OC; TI; OS; ES | 2.28 | 0.080 | 0.083 | 0.772 | 0.757 |

| Five-factor model | PC; OC; TI; OS; ES | 2.10 | 0.00 | 0.078 | 0.806 | 0.792 |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | 1.91 | 0.29 | |||||||||||

| 2 Age | 2.99 | 0.95 | −0.187 * | ||||||||||

| 3 Marriage | 1.89 | 0.39 | 0.087 | 0.321 ** | |||||||||

| 4 Position | 1.37 | 0.64 | −0.171 | 0.088 | −0.049 | ||||||||

| 5 Length of service | 3.11 | 1.10 | −0.189 * | 0.497 ** | 0.228 * | 0.073 | |||||||

| 6 Education | 1.33 | 0.60 | −0.117 | 0.146 | 0.056 | 0.439 ** | 0.048 | ||||||

| 7 Psychological contract violation | 2.14 | 0.70 | −0.148 | 0.069 | −0.124 | 0.256 ** | 0.134 | 0.261 ** | (0.86) | ||||

| 8 Turnover intention | 2.45 | 0.79 | −0.101 | −0.054 | −0.123 | 0.265 ** | 0.032 | 0.127 | 0.511 ** | (0.77) | |||

| 9 Organizational commitment | 3.45 | 0.53 | 0.049 | −0.018 | 0.062 | −0.259 ** | −0.062 | −0.237 * | −0.646 ** | −0.719 ** | (0.76) | ||

| 10 Organizational support | 3.27 | 0.60 | 0.074 | −0.057 | 0.041 | −0.221 * | −0.150 | −0.213 * | −0.604 ** | −0.343 ** | 0.502 ** | (0.79) | |

| 11 Emotional susceptibility | 3.81 | 0.56 | −0.018 | 0.006 | 0.021 | −0.022 | −0.135 | −0.170 | −0.202 * | −0.043 | 0.091 | 0.287 ** | (0.79) |

| Variables and Models | Organizational Commitment | Turnover Intention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Gender | −0.015 | −0.055 | −0.053 | −0.023 | −0.059 |

| Age | 0.035 | 0.034 | −0.095 | −0.093 | −0.071 |

| Marriage | 0.070 | −0.026 | −0.094 | −0.02 | −0.037 |

| Position | −0.184 | −0.094 | 0.241* | 0.171 | 0.109 |

| Length of service | −0.077 | 0.009 | 0.071 | 0.005 | 0.011 |

| Education | −0.164 | −0.043 | 0.031 | −0.062 | −0.091 |

| Psychological contract violation | −0.626 ** | 0.484 ** | 0.069 | ||

| Organizational commitment | −0.663 ** | ||||

| R2 | 0.094 | 0.434 | 0.092 | 0.295 | 0.544 |

| ΔR2 | 0.34 | 0.203 | 0.249 | ||

| F | 3.379 ** | 21.208 ** | 3.294 * | 11.581 ** | 28.765 ** |

| Mediating Model | Indirect Effect | SE | LLCL | ULCL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC→OC→TI | 0.466 | 0.069 | 0.339 | 0.612 |

| Variables and Models | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover Intention | Organizational Commitment | Turnover Intention | Turnover Intention | |

| Gender | −0.024 | −0.049 | −0.057 | −0.058 |

| Age | −0.092 | 0.028 | −0.073 | −0.074 |

| Marriage | −0.021 | −0.022 | −0.036 | −0.043 |

| Position | 0.169 | −0.084 | 0.112 | 0.090 |

| Length of service | 0.001 | 0.024 | 0.017 | 0.023 |

| Education | −0.064 | −0.037 | −0.088 | −0.093 |

| Psychological contract violation | 0.458 * | −0.531 * | 0.099 | 0.051 |

| Organizational Support | −0.045 | 0.165 | 0.066 | 0.008 |

| Organizational Commitment | −0.675 * | −0.686 * | ||

| Organizational Commitment * Organizational Support | 0.138 * | |||

| R2 | 0.267 | 0.428 | 0.525 | 0.563 |

| ΔR2 | 0.161 | 0.097 | 0.038 | |

| F | 10.143 * | 19.770 * | 25.709 * | 24.576 * |

| Variables and Models | Organizational Commitment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Gender | −0.053 | −0.023 | −0.022 |

| Age | −0.095 | −0.093 | 0.096 |

| Marriage | −0.094 | −0.02 | −0.021 |

| Position | 0.241 * | 0.171 | 0.168 |

| Length of service | 0.071 | 0.005 | 0.011 |

| Education | 0.031 | −0.062 | −0.053 |

| Psychological contract violation | 0.484 ** | 0.497 ** | |

| Emotional susceptibility | 0.042 | ||

| Psychological contract violation * Emotional susceptibility | −0.40 | ||

| R2 | 0.092 | 0.295 | 0.299 |

| ΔR2 | 0.203 | 0.04 | |

| F | 3.294 * | 11.581 ** | 9.089 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, H.; Wang, G.; Ghouri, M.W.A.; Deng, Z. Investigating the Impact of Psychological Contract Violation on Survivors’ Turnover Intention under the Downsizing Context: A Moderated Mediation Mechanism. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031770

Lv H, Wang G, Ghouri MWA, Deng Z. Investigating the Impact of Psychological Contract Violation on Survivors’ Turnover Intention under the Downsizing Context: A Moderated Mediation Mechanism. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031770

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Hao, Guofeng Wang, Muhammad Waleed Ayub Ghouri, and Zhuohang Deng. 2023. "Investigating the Impact of Psychological Contract Violation on Survivors’ Turnover Intention under the Downsizing Context: A Moderated Mediation Mechanism" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031770

APA StyleLv, H., Wang, G., Ghouri, M. W. A., & Deng, Z. (2023). Investigating the Impact of Psychological Contract Violation on Survivors’ Turnover Intention under the Downsizing Context: A Moderated Mediation Mechanism. Sustainability, 15(3), 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031770