Religious Liberty in Prisons under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act following Holt v Hobbs: An Empirical Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000 (RLUIPA)

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Selection

- The prisoner’s claim was brought and decided under RLUIPA. Prisoners often brought claims under the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause or the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. A decision was included only if the text of the decision revealed the case was disposed of under the Act rather than an alternative legal ground.

- The data was derived from published and indexed/” “unpublished” courts of appeals decisions. Most of Courts of Appeals decisions are decided as “unpublished.” This does not mean they are unavailable on various data bases but only that the circuit judges deciding the case concluded the holding will not be considered to have formal precedential value. However, in every other respect these decisions purport to following legal precedent applicable to the case before the court.

- The decision was rendered by one of the United States Circuit Courts of Appeals. Thus, United States District Court and U.S. Supreme Court decisions were not included in the data base.

- Prisoners bringing claims are or were incarcerated in state facilities. This is because RLUIPA only provides for religious accommodations to prisoners housed in state facilities.

- The cases were decided during the period following the Holt decision in January 2015. Those cases ranged from June 2012 to March 2018.

3.2. Decisional Categories

3.2.1. Procedural Dismissals

3.2.2. Merits Decisions

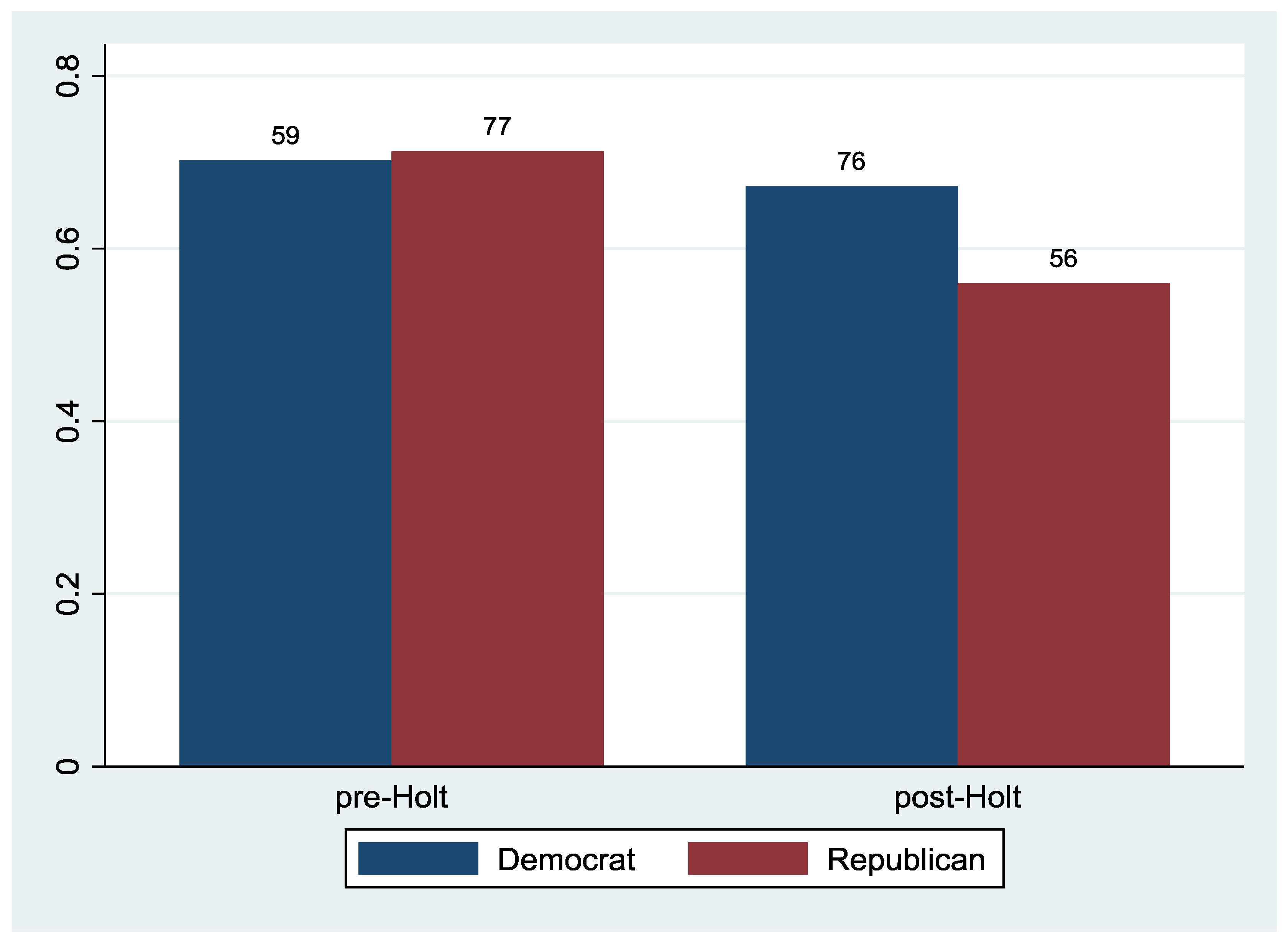

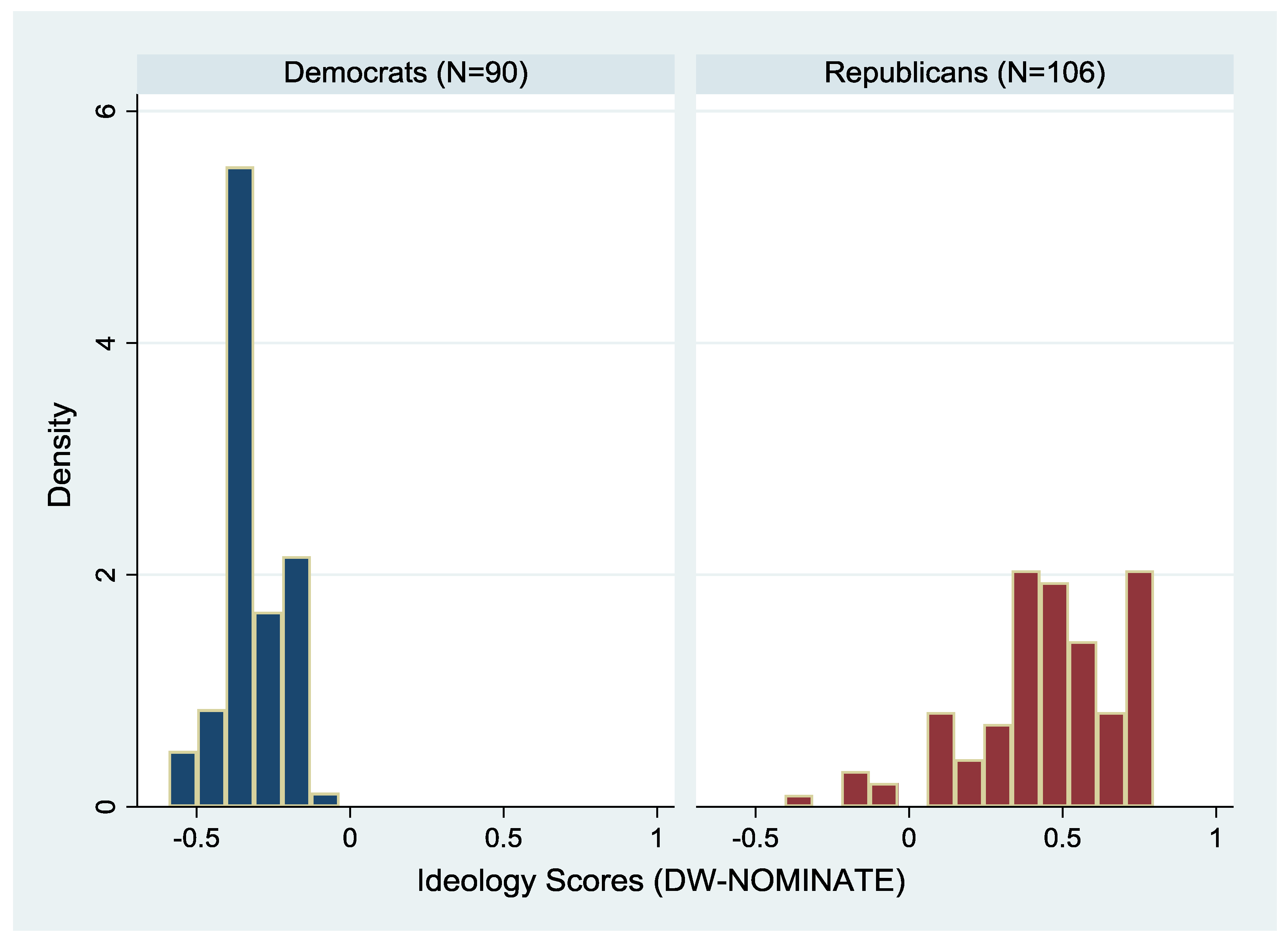

3.2.3. Courts of Appeals Voting Patterns

3.2.4. Case Locating and Coding

4. Results

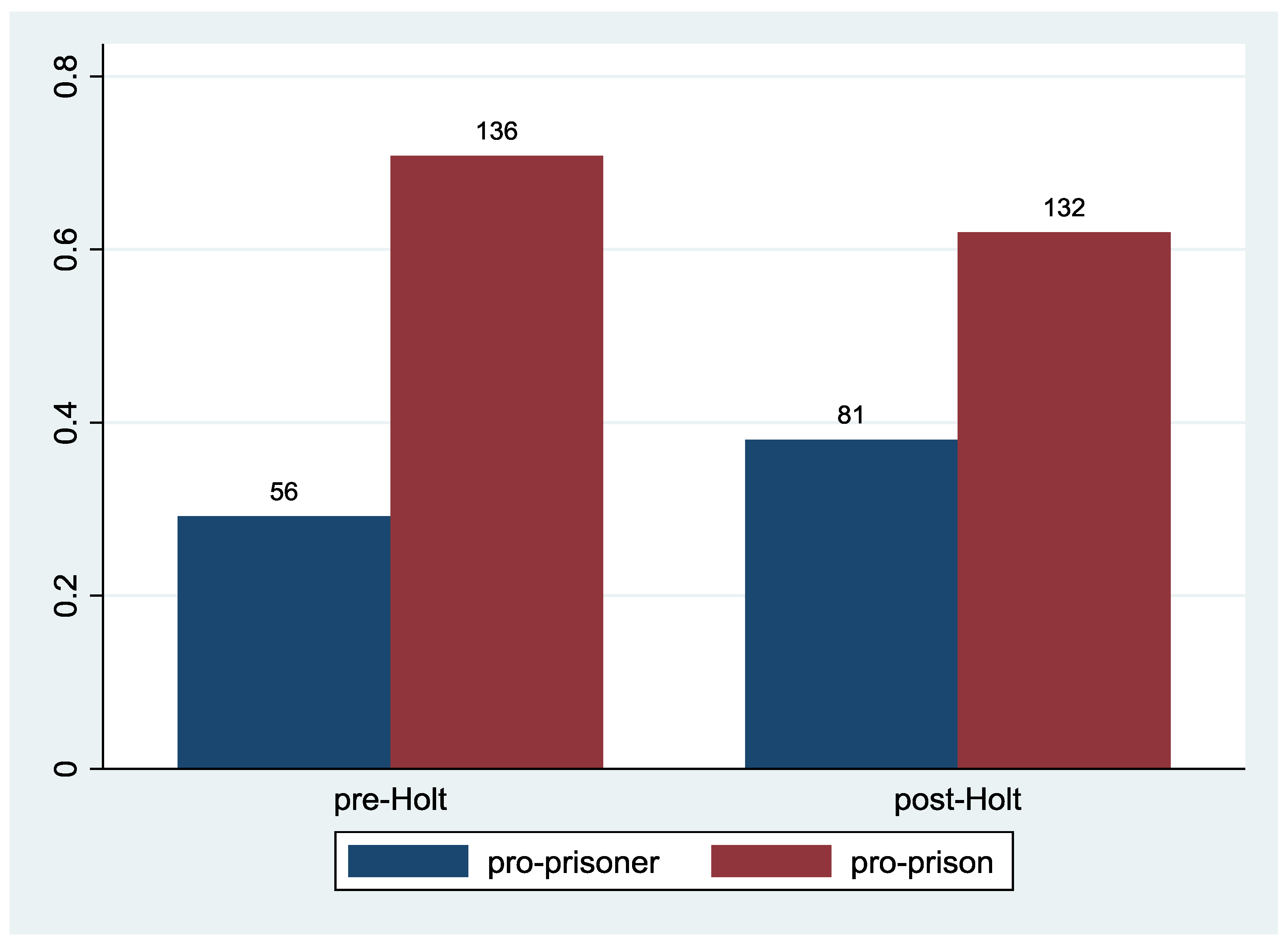

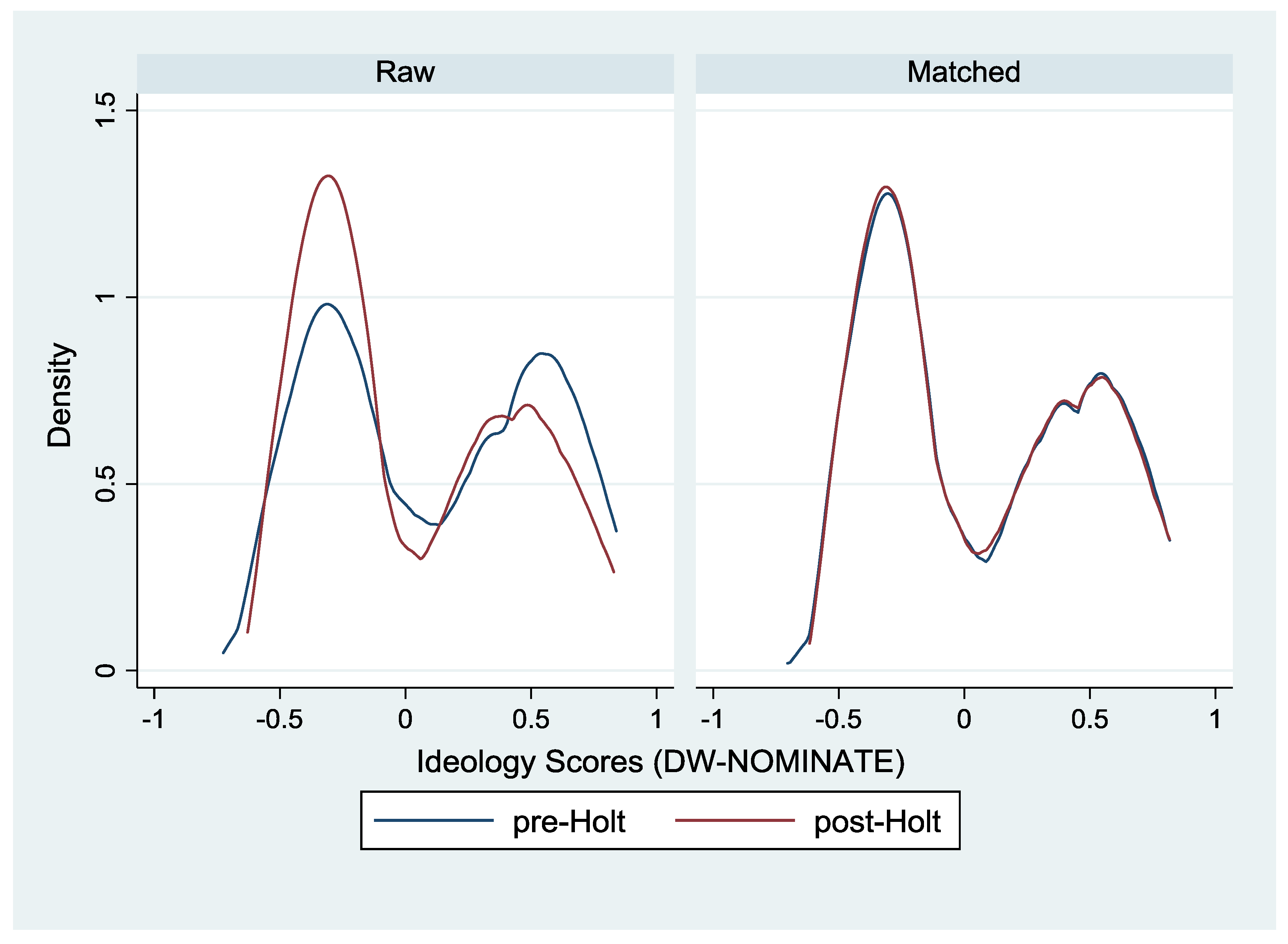

Matching Analysis

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bollman, Barrick. 2018. Deference and Prisoner Accommodations Post-Holt: Moving RLUIPA toward ‘Strict in Theory, Strict in Fact’. Northwestern University Law Review 112: 839–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gaubatz, Derek L. 2005. RLUIPA at Four: Evaluating the Success and Constitutionality of RLUIPA’s Prisoner Provisions. Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy 28: 501–10. [Google Scholar]

- Goce Beneficente. 2015. Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act—Religious Liberty Holt v. Hobbs. Harvard Law Review 129: 351–57. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, Luke W., and Rachel N. Busick. 2018. Sex, Drugs, and Eagle Feathers: An Empirical Study of Federal Religious Freedom Cases. Seton Hall Law Review 48: 353–401. [Google Scholar]

- Laycock, Douglas, and Luke W. Goodrich. 2012. RLUIPA: Necessary, Modest, and Under-Enforced. Fordham Urban Law Journal 39: 1021–41. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, David M. 2016a. To Seek a Newer World: Prisoner’s Rights at the Frontier. Michigan Law Review First Impressions 114: 124–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, David M. 2016b. Lenient in Theory, Dumb in Fact: Prison, Speech, and Scrutiny. The George Washington Law Review 84: 972–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisk, Gregory C., and Michael Heise. 2012. Ideology ‘All the Way Down’? An Empirical Study of Establishment Clause Decisions in Federal Courts. Michigan Law Review 110: 1201–64. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | (Goodrich and Busick 2018, n. 3) (Collecting articles concerned with the threat caused by federal statutory enactments expanding protection for religious adherents). |

| 2 | Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520 (1993) (city’s ordinance, prohibiting ritual animal sacrifices, violated the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause failed to survive the rigors of strict scrutiny; it singled out activities of Santeria faith and suppressed more religious conduct than was necessary to achieve their stated ends); but see, O’ Lone v. Estate of Shabazz, 482 U.S. 342 (1987) (so long as the policy is reasonably related to legitimate penological objectives, the Free Exercise Clause does not require prisons to show there are no reasonable alternatives that would accomplish its security needs before it infringes on an inmate’s free exercise of religion). |

| 3 | See, e.g., Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 (1962) (holding that a state statute authorizing a short voluntary prayer for recitation at the start of the school day violates the establishment of religious clause of the First Amendment); Lee v. Weisman, 505 U.S. 577 (1992) (including clergy who offer prayers as part of an official public-school graduation ceremony is forbidden by the Establishment Clause); Larkin v. Grendel’s Den, Inc., 459 U.S. 116 (1982) (vesting in the governing bodies of churches and schools the power to prevent issuance of liquor licenses for premises located near the church or school violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment); but see, Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709 (2005) (Section 3 of RLUIPA, on its face, qualifies as a permissible accommodation to religious exercise that is not barred by the Establishment Clause); Corporation of Presiding Bishop of Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints v. Amos, 483 U. S. 327 (1987) (upholding against an Establishment Clause challenge a provision exempting religious organizations from the prohibition against religion-based employment discrimination in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964). |

| 4 | See, e.g., The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, Pub. L. No. 103-141, 107 Stat. 1488 (16 November 1993), codified at 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb through 2000bb 4. This was introduced by Congressman Chuck Schumer (D-NY) on 11 March 1993. A unanimous U.S. House and a nearly unanimous—three senators voted against passage—passed the bill, and President signed it into law. |

| 5 | 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000cc to cc-5 (2012). |

| 6 | See, e.g., Smith v. Perlman, 658 Fed Appx 606 (2nd Cir. 2016); Holland v. Goord, 758 F.3d 215, 224 (2nd Cir. 2014) (observing that RLUIPA stands in contrast to the Free Exercise Clause’s less demanding rational basis test); Madison v. Ritter, 411 F.Supp.2d 645, aff’d in part, and reversed in part, 474 F.3d 118 (4th Cir. Year) (observing that RLUIPA provides more protection than the First Amendment) and O’Lone v. Estate of Shabazz, 482 U.S. 342, 349 (1987) (quoting Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78, 79 (1987)). |

| 7 | |

| 8 | See, e.g., (Bollman 2018) (applying descriptive statistics to study among other things the effects of Holt v. Hobbs, U.S., 135 S.Ct. 853 (2015) on case outcomes at the U.S. District Courts and U.S. Courts of Appeals). |

| 9 | 135 S.Ct. 853 (2015). |

| 10 | Id. |

| 11 | 544 U.S. 709, 712–13 (2005). |

| 12 | (Sisk and Heise 2012) (observing strong ideological voting in Establishment Clause cases). |

| 13 | Id. |

| 14 | 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc–1(a). See, Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709 (2005) (describing test). “[A] prison cannot meet its burden to prove least restrictive means unless it demonstrates that it has actually considered and rejected the efficacy of less restrictive measures before adopting the challenged practice.” Shakur v. Schriro, 514 F.3d 878, 890 (9th Cir. 2008) (quoting Warsoldier v. Woodford, 418 F.3d 989, 999 (9th Cir. 2005). |

| 15 | 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc–5(4). It states government under the Act “(A) means (i) a State, county, municipality, or other governmental entity created under the authority of a State; (ii) any branch, department, agency, instrumentality, or official of any entity listed in clause (i); and any other person acting under color of State law…” See, e.g., Wood v. Yordy, 753 F.3d 899, 902 (9th Cir. 2014) (dismissing action against officials in their individual capacities, since RLUIPA does not authorize suits against persons other than in an official capacity). |

| 16 | 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc–5(4) (limiting reach of statute to state entities); Daley v. Lappin, 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 100624 (M.D. Pa 7 September 2011) (holding that a federal prisoner is ineligible for relief under RLUIPA), vacated and remanded on other grounds, 555 Fed. Appx. 161 (2014). |

| 17 | 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc–2(a) (“A person may assert a violation of this chapter as a claim or defense in a judicial proceeding and obtain appropriate relief against a government”). |

| 18 | See, e.g., Sossamon v. Texas, 131 S.Ct. 1651 (2011); Sharp v. Johnson, 669 F.3d 144, 155 (3d Cir. 2012); Rendelman v. Rouse, 569 F.3d 182, 189 n. 2 (4th Cir. 2009); Wright v. Lassiter, 633 Fed Appx 150 (4th Cir. 2016) (per curium) (unpublished disposition). |

| 19 | Begnoche v. DeRose, 2017 U.S. App. LEXIS 1386*7, note 6 (3d Cir. 2017) citing Sharp v. Johnson, 669 F.3d 144, 155 (3d Cir. 2012) (citing Sossamon v. Texas, 563 U.S. 277, 131 S.Ct. 1651, 1655, 1660 (2011). |

| 20 | Davilia v. Marshall, 2016 WL 2941929*2 (11th Cir. 2016); Begnoche v. DeRose, 2017 U.S. App. LEXIS 1386*7, note 6 (3d Cir. 2017); Holland v. Goord, 758 F.3d 215, 224 (2nd Cir. 2014) (RLUIPA does not authorize claims for monetary damages against state officers in either their individual or official capacities) (citing Washington v. Gonyea, 731 F.3d 143, 145-46 (2nd Cir. 2013); Stewart v. Beach, 701 F.3d 1322, page (10th Cir. 2012); Nelson v. Miller, 570 F.3d 868, 886–89 (7th Cir.2009); Rendelman v. Rouse, 569 F.3d 182, 188–89 (4th Cir.2009); Sossamon v. Lone Star State of Tex., 560 F.3d 316, 328–29 (5th Cir.2009), aff’d on other grounds by 131 S.Ct. 1651 (2011) Smith v. Allen, 502 F.3d 1255, 1271–75 (11th Cir.2007), abrogated on other grounds by Sossamon, 131 S.Ct. 1651. |

| 21 | See, e.g., Smith, 502 F.3d at 1272–75 (“[I]t is clear that the ‘contracting party’ in the RLUIPA context is the state prison institution that receives federal funds; put another way, these institutions are the ‘grant recipients’ that agree to be amenable to suit as a condition to receiving funds—but their individual employees are not ‘recipients’ of federal funding.”). Although the Spending Clause basis for suits under RLUIPA is clear, whether there is as well a Commence Clause basis for such claims is unclear. See, Haight v. Thompson, 763 F.3d 554 (6th Cir. 2014) (Cole, concurring). |

| 22 | 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000cc–1(b), 2000cc–2(a). See, e.g., Nelson v. Miller, 570 F.3d 868, 886 (7th Cir. 2009); Rendelman v. Rouse, 569 F.3d 182, 189 (4th Cir. 2009); Washington v. Gonyea, 731 F.3d 143, 146 (2nd Cir. 2013) (commenting without deciding that an adequate pleading under RLUIPA commence clause provision requires stating fact showing how the restriction on religious rights had an effect on interstate or foreign commerce). |

| 23 | See, Banks v. Secretary, Pennsylvania Dep’t of Corrections, 601 Fed Appx. 101, **5) (3d Cir. 2015) (denying prison-specific injunctive and declaratory relief, holding that claims were moot on transfer because injunctive and declaratory relief for injury at institution where he no longer resided could have no effect on defendant’s behavior toward him). |

| 24 | The Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) provides that “[n]o action shall be brought with respect to prison conditions … by a prisoner confined in any … prison … until such administrative remedies as are available are exhausted.” 42 U.S.C. § 1997e(a). The purpose of the exhaustion requirement is twofold. See, Woodford v Ngo, 548 U.S. 81, 89 (2006). First, it “protects administrative agency authority” by allowing the agency to “correct its own mistakes” rather than being immediately “haled into federal court.” Id. (internal citations omitted). Second, it promotes efficiency insofar as administrative review processes are generally faster and more economical than is litigation. Id. Even where the parties subsequently seek judicial remedies, the administrative-review process often produces a useful record to ease and expedite further proceedings. Id. See also, McCarthy v. Madigan, 503 U.S. 140, 150 (1992). |

| 25 | See, Daley v. Lappin, 555 Fed Appx 161, 167 (3 d Cir. 2014) (defendant’s failure to assert exhaustion defense in district court cannot be raised for the first time on appeal). |

| 26 | 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc–2(b); Chance v. Tex. Dep’t of Criminal Justice, 730 F.3d 404, 410 (5th Cir.2013). |

| 27 | Holt v. Hobbs, 135 S. Ct. 853, 862 (quoting Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., U.S., 134 S.Ct. 2751, 2775, 189 L.Ed.2d 675 (2014)). See, e.g., Washington v. Klemm, 497 F.3d 272, 28 (3d Cir. 2007) (for purposes of RLUIPA, substantial burden exists where: a follower is forced to choose between following the precepts of his religion and forfeiting benefits otherwise generally available to other inmates versus abandoning one of the precepts of his religion in order to receive a benefit; or , the government puts substantial pressure on an adherent to substantially modify his behavior and to violate his beliefs); Smith v. Governor for the State of Alabama, 562 Fed. Appx. 806 (11th Cir. 2014) (granting summary judgment to defendant on ground that plaintiff failed RLUIPA’s substantial burden test which “requires at a minimum that a RLUIPA plaintiff demonstrate that government’s denial of a particular religious item or observance was more than an inconvenience to one’s religious practice.”). |

| 28 | See, e.g., Holt v. Hobbs, 135 S.Ct. 853, 860 (2015); Williams v. Wilkinson, 645 Fed. Appx. 692, 216 U.S. App. LEXIS 6877 (10th Cir. 2016) (applying standard to prisoner’s request to attend communal services and be provided kosher food despite his Muslim affiliation). |

| 29 | See, e.g., United States v. Quaintance, 608 F.3d 717, 720–23 (10th Cir. 2010) (RLUIPA requires courts to protect against only burdens on sincere religious exercises, not personal offenses); Mutawakkil v. Huibregtse, 735 F.3d 524, 527 (7th Cir. 2013) (“[Plaintiff] says that it would be preferable (from his perspective) if he were allowed to use just his spiritual name … but preference or convenience is not the standard.”); Jahad Ali v. Wingert, 569 Fed. Appx 562 (10th Cir. 2014) (no burden where prison officials used both committed and adopted religious name). |

| 30 | See, e.g., Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709, 725 n.13 (“[a]lthough RLUIPA bars inquiry into whether a particular belief or practice is central to a prisoner’s religion, the Act does not preclude inquiry into the sincerity of a prisoner’s professed religiosity.”); Abdulhaseeb v. Calbone, 600 F.3d 1301, 1318 (10th Cir. 2010) (it is not until the summary-judgment phase that “the burden shifts to the defendants to show the substantial burden results from a compelling governmental interest and that the government has employed the least restrictive means of accomplishing its interest.”); Spratt v. R.I. Dep’t of Corrections, 482 F.3d 33, 38 (1st Cir. 2007) (citing 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc-2(b)). |

| 31 | See, e.g., Kay v. Bemis, 500 F.3d 1214, 1219 (10th Cir. 2007). |

| 32 | See, Yellowbear v. Lampert, 741 F.3d 48, 55 (10th Cir. 2014) (citing Thomas v. Review Bd. of Ind. Emp’t Sec. Div., 450 U.S. 707 (1981). |

| 33 | 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc–1(a); Holt, 135 S.Ct. at 863; Ali v. Williams, 822 F.3d 776, 786 (5th Cir. 2016)(describing the least restrictive means test as “exceptionally demanding”) (citing Hobby Lobby, 134 S.Ct. at 2780). |

| 34 | Holt, 135 S.Ct. at 860. |

| 35 | Id. (quoting 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc–3(g)). |

| 36 | Hobby Lobby, 134 S.Ct. at 2781 (citing 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc–3(c)); see also Holt, 135 S.Ct. at 860.e |

| 37 | Holt, 135 S.Ct. at 860 (quoting 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc–5(7) (A)). Indeed, atheism may fall within RLUIPA’s protective ambit. See, e.g., Kaufman v. McCaughtry, 419 F.3d 678, 683–84 (7th Cir. 2005) (recognizing atheists as a religious group but denying an accommodation since it would be impracticable to spend limited resources on only two prisoners). |

| 38 | Holt, 135 S.Ct. at 866. |

| 39 | Id. |

| 40 | Id. at 864. |

| 41 | Id. |

| 42 | Id. (quoting Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, 546 U.S. 418, 434, (2006)). |

| 43 | Id. |

| 44 | 42 U.S.C. § 1997e(a). See, Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709, 723 n. 12 (2005) (“[A] prisoner may not sue under RLUIPA without first exhausting all available administrative remedies.”). |

| 45 | 28 U.S.C. § 1658(a). See, e.g., Al-Amin v. Shear, 325 Fed. Appx 190, 193 (4th Cir. 2009) [add citations]. |

| 46 | 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb et seq. |

| 47 | 494 U.S. 872 (1990). |

| 48 | Id. at 878–82. |

| 49 | See, Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205, 214, 219 (1972) and Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398, 403, 406 (1963). |

| 50 | The Court held that religiously motivated persons enjoy no special right to violate otherwise valid laws, provided the laws are of general application and do not single out religiously motivated conduct for adverse treatment. Smith at 878. Smith, who was employment by the Oregon government had participated in a Native American Church ritual that involved ingestion of Peyote, a banned substance in Oregon. Smith’s boss found out about the ceremony and fired him. Smith sought but was denied unemployment benefits by the state on the ground that he lost his job through criminal misconduct. Id. 882–85. However, under rationale basis scrutiny, the Oregon law withstood the challenge since it was neutral and was not designed to target any religious group. |

| 51 | O’Lone v. Shabazz, 482 U.S. 342, 349 (1987) (quoting Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78, 79 (1987)). That said, there is tension between O’Lone v. Shabazz and Turner v. Safley, “which create a First Amendment duty of religious accommodations in prisons, and … Employment Division v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990), which denies a constitutional duty of religious accommodations in broad terms yet without overruling O’Lone or Turner.” Lewis v. Sternes, 712 F.3d 1083, 1085 (7th Cir. 2013) (Posner, J.) (discussing issue). |

| 52 | See, 42 U.S.C. § 2000bb(b)(I)(2004); Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S.,134 S.Ct. 2751, 2760–61 (2014). |

| 53 | |

| 54 | Section 5 states: “The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” U.S. Constitution, amend 15, sect. 5. In commenting on City of Boerne then Judge Gorsuch wrote: “… the Court held that RFRA stretched the federal hand too far into places reserved for the states and exceeded Congress’s Section 5 enforcement authority under the Fourteenth Amendment. As a result, the Court held RFRA unconstitutional as applied to the states, though still fully operational as applied to the federal government.” Yellowbear v. Lampert, 741 F.3d 48, 52 (10th Cir. 2014) (citing City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507, 529–36). |

| 55 | 521 U.S. 507 (1997) |

| 56 | Id. at 532–33. |

| 57 | See, Gonzales v. O Centro Esperita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, 546 U.S. 418 (2006) (member of sect have RFRA right to sacramental use of hoasca, a hallucinogenic tea despite being banned by the Controlled substance Act, since the government could not demonstrate it had a compelling interest in barring the sacramental use of this drug); See, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S.,134 S.Ct. 2751, 2760–61 (2014). |

| 58 | See, e.g., Kikumura v. Gallegos, 242 F.3d 950 (10th Cir. 2001); In re: Bruce Young, 141 F.3d 854 (8th Cir. 1998). [find citations]. |

| 59 | We recognize that some judges might dispose of cases they were inclined to dismiss anyway by simply finding no substantial burden and thereby avoid the demanding work of analyzing the governmental interest asserted by prison officials and whether they applied the least restrictive means to achieve their policy objectives. Although the high proportion of cases dismissed on no substantial burden ground suggests this could be the case this is far from certain. |

| 60 | (Bollman 2018) (Applying descriptive statistics to study among other things the effects of Holt v. Hobbs, 135 S.Ct. 853 (2015) on case outcomes at the U.S. District Courts and U.S. Courts of Appeals). |

| 61 | Holt v. Hobbs, 135 S.Ct. at 841–42 notes 11 & 12; 851–57, notes 76–138 (citing cases). |

| 62 | Here, we use the same formula employed in (Sisk and Heise 2012), where judges are assigned the DW-NOMINATE score of the appointing President if there is no Senator of the same party in the judge’s state, the score of the Senator if there is one of the same party as the appointing President for the judge’s state, or the mean of the scores of both Senators if there are two Senators of the same party as the appointing President for the judge’s state. However, whereas Sisk and Heise use “common-space” DW-NOMINATE scores, we use the specific scaling for the Senate, since only Senators are involved in the judicial appointment process. |

| 63 | Id. at 848. |

| 64 | 42 U.S.C. 2000cc-5(7)(A). The Supreme Court has held however, that this belief must be “sincer[e].” Cuttter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709, 725 n. 13 (2005). This standard broadened the definition of substantial burden compared to the one contained in RFRA. See, e.g., Hunter v. Baldwin, No. 95-35330, 1996 WL 95046 (9th Cir. Mar. 5, 1996). |

| 65 | Holt v. Hobbs, 135 S.Ct. 853, 862 (2015). |

| 66 | Our findings tract those of Bollman who observed that nearly 47% of the post-Holt cases he studied were dismissed on no substantial burden ground. See, e.g., (Bollman 2018). Since his data base was comprised of both U.S. District Court and Court of Appeals decisions those results are not directly comparable to ours. |

| 67 | See, e.g., (Bollman 2018) (speculating about such a possibility but generally finding little empirical support for this proposition). |

| ATE | |

|---|---|

| Average probability change post-Holt | −0.13 *** |

| (0.04) | |

| N | 405 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wasserman, L.M.; Connolly, J.P.; Kerley, K.R. Religious Liberty in Prisons under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act following Holt v Hobbs: An Empirical Analysis. Religions 2018, 9, 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9070210

Wasserman LM, Connolly JP, Kerley KR. Religious Liberty in Prisons under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act following Holt v Hobbs: An Empirical Analysis. Religions. 2018; 9(7):210. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9070210

Chicago/Turabian StyleWasserman, Lewis M., John P. Connolly, and Kent R. Kerley. 2018. "Religious Liberty in Prisons under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act following Holt v Hobbs: An Empirical Analysis" Religions 9, no. 7: 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9070210

APA StyleWasserman, L. M., Connolly, J. P., & Kerley, K. R. (2018). Religious Liberty in Prisons under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act following Holt v Hobbs: An Empirical Analysis. Religions, 9(7), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9070210