The Effects of Provincial and Individual Religiosity on Deviance in China: A Multilevel Modeling Test of the Moral Community Thesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Moral Communities Thesis

3. Religion in China

4. Hypotheses

5. Methods

5.1. Data

5.2. Measurement

5.2.1. Dependent Variables

5.2.2. Individual-Level Independent Variables

5.2.3. Province-Level Independent Variables

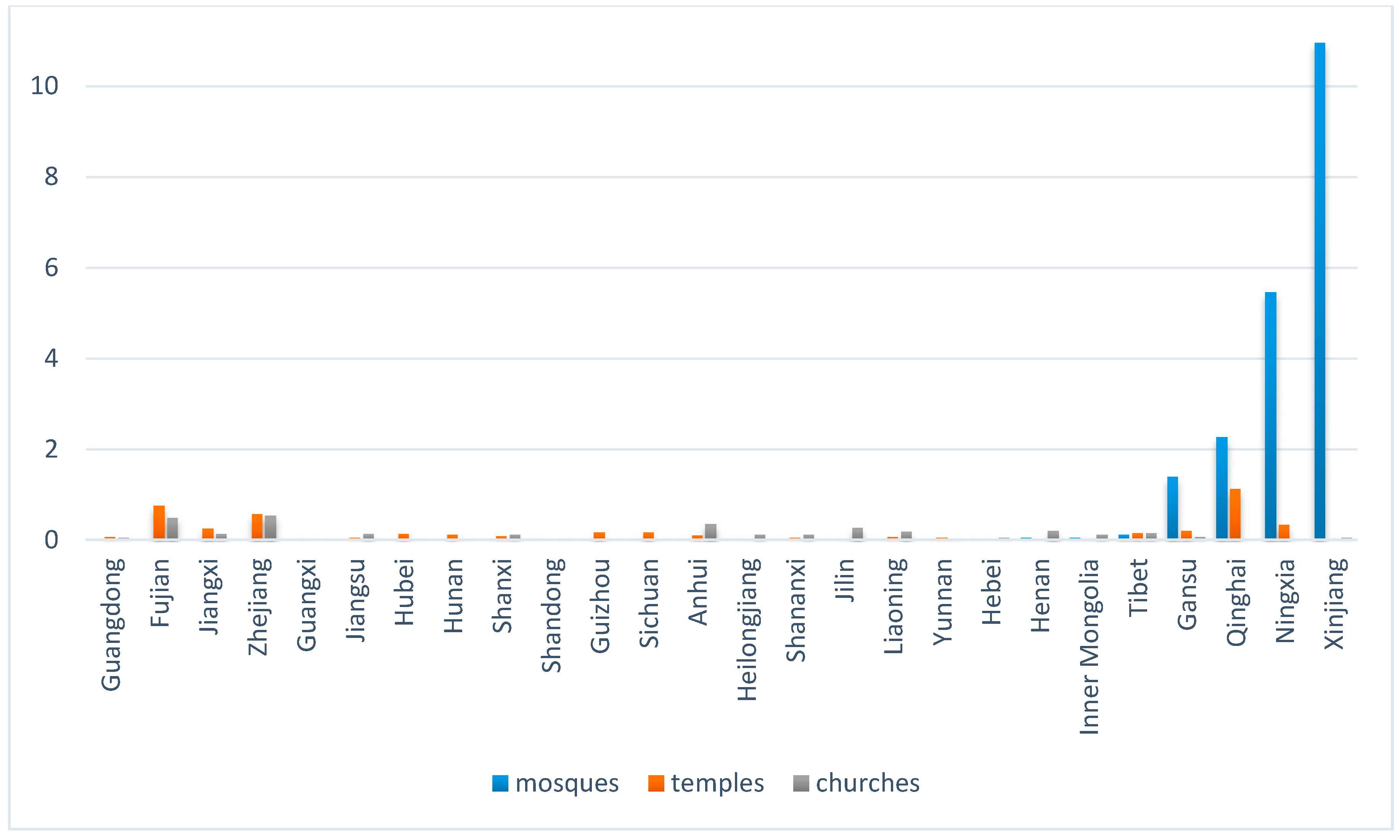

5.2.4. Analytic Strategy

6. Results

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical Approval

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamczyk, Amy. 2008. The Effects of Religious Contextual Norms, Structural Constraints, and Personal Religiosity on Abortion Decisions. Social Science Research 37: 657–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamczyk, Amy, and Brittany E. Hayes. 2012. Religion and Sexual Behaviors Understanding the Influence of Islamic Cultures and Religious Affiliation for Explaining Sex Outside of Marriage. American Sociological Review 77: 723–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, Stan L., Bruce A. Chadwick, and David S. Alcorn. 1977. Religiosity and Deviance: Application of an Attitude-Behavior Contingent Consistency Model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 16: 263–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, Stephen J., and John P. Hoffmann. 2008. Religiosity, Peers, and Adolescent Drug Use. Journal of Drug Issues 38: 743–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, Colin J., and Bradley R. E. Wright. 2001. ‘If You Love Me, Keep My Commandments’: A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Religion on Crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 38: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Shuming, Changzhen Wang, and Miao Shui. 2014. Spatial Study of Religion with Spatial Religion Explorer. Paper presented at 2014 22nd International Conference on Geoinformatics, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, June 25–27; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Benda, Brent B. 2002. Religion and Violent Offenders in Boot Camp: A Structural Equation Model. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 39: 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benda, Brent B., and Robert Flynn Corwyn. 2001. Are the Effects of Religion on Crime Mediated, Moderated, and Misrepresented by Inappropriate Measures? Journal of Social Service Research 27: 57–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, Steven R., and Mervin White. 1974. Hellfire and Delinquency: Another Look. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 13: 455–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Fang, Dewen Wang, and Yang Du. 2002. Regional Disparity and Economic Growth in China: The Impact of Labor Market Distortions. China Economic Review 13: 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Shixiong. 2012. Socioeconomic Value of Religion and the Impacts of Ideological Change in China. Economic Modelling 29: 2621–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Cheris Shun-ching. 2004. The Falun Gong in China: A Sociological Perspective. The China Quarterly 179: 665–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Hsinchih. 1995. The Development of Taiwanese Folk Religion, 1683–1945. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, May 31. Available online: https://digital.lib.washington.edu:443/researchworks/handle/1773/8853 (accessed on 12 November 2017).

- Cochran, John K., and Ronald L. Akers. 1989. Beyond Hellfire: An Exploration of the Variable Effects of Religiosity on Adolescent Marijuana and Alcohol Use. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 26: 198–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, John K., Peter B. Wood, and Bruce J. Arneklev. 1994. Is the Religiosity-Delinquency Relationship Spurious? A Test of Arousal and Social Control Theories. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 31: 92–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, Katie E., David Pettinicchio, and Blaine Robbins. 2012. Religion and the Acceptability of White-Collar Crime: A Cross-National Analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 542–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner. 1932. Was Confucius Agnostic? T’oung Pao 29: 55–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Elizabeth Van Wie. 2008. Uyghur Muslim Ethnic Separatism in Xinjiang, China. Asian Affairs: An American Review 35: 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, Kenneth. 2003. Local Communal Religion in Contemporary South-East China. The China Quarterly 174: 338–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, Emily C. 2008. ‘Cult,’Church, and the CCP: Introducing Eastern Lightning. Modern China 35: 96–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, Emile. 1926. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life a Study in Religious Sociology. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1976. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Formes Élémentaires de La Vie religieuse. English. London: Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Lee. 1987. Religiosity and Criminality from the Perspective of Arousal Theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 24: 215–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Lee, and James Peterson. 1996. Crime and Religion: An International Comparison among Thirteen Industrial Nations. Personality and Individual Differences 20: 761–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., Jeffrey A. Burr, and Patricia L. McCall. 1997. Religious Homogeneity and Metropolitan Suicide Rates. Social Forces 76: 273–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuchtwang, Stephan. 2010. The Anthropology of Religion, Charisma, and Ghosts: Chinese Lessons for Adequate Theory. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Finke, Roger, and Amy Adamczyk. 2008. Cross-National Moral Beliefs: The Influence of National Religious Context. Sociological Quarterly 49: 617–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finke, Roger, and Rodney Stark. 2005. The Churching of America, 1776–2005: Winners and Losers in Our Religious Economy. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gladney, Dru C. 1996. Muslim Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic. Cambridge: Harvard Univ Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Grim, Brian J., and Roger Finke. 2006. International Religion Indexes: Government Regulation, Government Favoritism, and Social Regulation of Religion. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 2. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4254791/ (accessed on 12 November 2017).

- Grim, Brian J., and Roger Finke. 2007. Religious Persecution in Cross-National Context: Clashing Civilizations or Regulated Religious Economies? American Sociological Review 72: 633–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, W. Byron, Graeme Newman, and Charles Corrado. 1987. Islam, Modernization and Crime: A Test of the Religious Ecology Thesis. Journal of Criminal Justice 15: 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, Mohammed M. 2004. From Marginalization to Massacres: Explaining GIA Violence in Algeria. In Islamic Activism: A Social Movement Theory Approach. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, Paul. 2006. Does Religion Really Reduce Crime? Journal of Law and Economics 49: 147–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Paul C., and Gary L. Albrecht. 1977. Hellfire and Delinquency Revisited. Social Forces 55: 952–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, Travis, and Rodney Stark. 1969. Hellfire and Delinquency. Social Problems 17: 202–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Anning. 2013. Generalized Trust among Christians in Urban China: Analysis Based on Propensity Score Matching. Current Sociology 61: 1021–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Gary F, and L. Erickson Maynard. 1979. The Religous Factor and Delinquency: Another Look at the Hellfire Hypothesis. The Religous Dimension: New Directions in Quantitative Research 3: 157–77. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Byron R. 1987. Religiosity and Institutional Deviance: The Impact of Religious Variables upon Inmate Adjustment. Criminal Justice Review 12: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Byron, and Sung Joon Jang. 2011. Crime and Religion: Accessing the Role of the Faith Factor. In Comtemporary Issues in Criminological Theory and Research: The Role of Social Institution. Belmont: Wadsworth, pp. 117–50. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Byron R., Sung Joon Jang, Spencer De Li, and David Larson. 2000. The ‘Invisible Institution’ and Black Youth Crime: The Church as an Agency of Local Social Control. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 29: 479–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junger, Marianne, and Wim Polder. 1993. Religiosity, Religious Climate, and Delinquency among Ethnic Groups in the Netherlands. British Journal of Criminology 33: 416–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koesel, Karrie J. 2014. Religion and Authoritarianism: Cooperation, Conflict, and the Consequences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Matthew R. 2006. The Religious Institutional Base and Violent Crime in Rural Areas. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45: 309–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Matthew R., and John P. Bartkowski. 2004. Love Thy Neighbor? Moral Communities, Civic Engagement, and Juvenile Homicide in Rural Areas. Social Forces 82: 1001–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Feng, and Jianhua Xu. 2004. Regional Economic Disparity in China: Empirical Analysis on Gini Index and Theil Index. Research on Cooperation between East and West in China 1: 60–85. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, Richard. 1998. China’s Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil Society. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maimon, David, and Danielle C. Kuhl. 2008. Social Control and Youth Suicidality: Situating Durkheim’s Ideas in a Multilevel Framework. American Sociological Review 73: 921–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsiglia, Flavio Francisco, Stephen Kulis, Tanya Nieri, and Monica Parsai. 2005. God Forbid! Substance Use among Religious and Nonreligious Youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 75: 585–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, John Kevin. 1990. Crime and Religion: A Denominational and Community Analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 29: 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovadia, Seth, and Laura M. Moore. 2010. Decomposing the Moral Community: Religious Contexts and Teen Childbearing. City & Community 9: 320–34. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, David A., and Philip L. Wickeri. 2011. Chinese Religious Life. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, Pitman B. 2003. Belief in Control: Regulation of Religion in China. The China Quarterly 174: 317–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, Stephen W., Bryk Anthony, Fai Cheong Yuk, and Congdon Richard. 2004. HLM 6: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Lincolnwood: Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus, Mark D. 2003. Moral Communities and Adolescent Delinquency. Sociological Quarterly 44: 523–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, Albert Lewis, and Albert J. Reiss. 1970. The Religious Factor and Delinquent Behavior. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 7: 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, Peer, Manfred Te Grotenhuis, and Frans Van Der Slik. 2002. Education, Religiosity and Moral Attitudes: Explaining Cross-National Effect Differences. Sociology of Religion 63: 157–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, Meir, and Robert Paul Weller. 1996. Unruly Gods: Divinity and Society in China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sloane, Douglas M., and Raymond H. Potvin. 1986. Religion and Delinquency: Cutting Through the Maze. Social Forces 65: 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, Steven, and Augustine J. Kposowa. 2011. Religion and Suicide Acceptability: A Cross-National Analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, Rodney. 1996. Religion as Context: Hellfire and Delinquency One More Time. Sociology of Religion 57: 163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney. 2001. Gods, Rituals, and the Moral Order. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40: 619–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney, Lori Kent, and Daniel P. Doyle. 1982. Religion and Delinquency: The Ecology of a ‘Lost’ Relationship. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 19: 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney, and Xiuhua Wang. 2015. A Star in the East: The Rise of Christianity in China, 1st ed.West Conshohocken: Templeton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sturgis, Paul W., and Robert D. Baller. 2012. Religiosity and Deviance: An Examination of the Moral Community and Antiasceticism Hypotheses among U.S. Adults. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 809–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Anna. 2013. Confucianism as a World Religion: Contested Histories and Contemporary Realities. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tamney, Joseph. 1998. Asian Popular Religions. In Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Edited by William H. Swatos. Lanham: Rowman Altamira. [Google Scholar]

- Tittle, Charles R., and Michael R. Welch. 1983. Religiosity and Deviance: Toward a Contingency Theory of Constraining Effects. Social Forces 61: 653–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trawick, Michelle W., and Roy M. Howsen. 2006. Crime and Community Heterogeneity: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion. Applied Economics Letters 13: 341–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Lily L. 2007. Accountability without Democracy: Solidary Groups and Public Goods Provision in Rural China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tubergen, Frank, Manfred te Grotenhuis, and Wout Ultee. 2005. Denomination, Religious Context, and Suicide: Neo-Durkheimian Multilevel Explanations Tested with Individual and Contextual Data. American Journal of Sociology 111: 797–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, John M., Ryoko Yamaguchi, Jerald G. Bachman, Patrick M. O’Malley, John E. Schulenberg, and Lloyd D. Johnston. 2007. Religiosity and Adolescent Substance Use: The Role of Individual and Contextual Influences. Social Problems 54: 308–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiuhua, and Sungjoon Jang. 2017. Relationships between Religion and Deviance in a Largely Irreligious Country: Findings from the 2010 China General Social Survey. Deviant Behavior 38: 1120–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Max, and Hans H. Gerth. 1953. The Religion of China, Confucianism and Taoism. Philosophy 28: 187–89. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, Michael R., Charles R. Tittle, and Thomas Petee. 1991. Religion and Deviance among Adult Catholics: A Test of the ‘Moral Communities’ Hypothesis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 30: 159–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, Jacqueline E. 2004. Official vs. Underground Protestant Churches in China: Challenges for Reconciliation and Social Influence. Review of Religious Research 46: 169–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Ching-kun. 1961. Religion in Chinese Society: A Study of Contemporary Social Functions of Religion and Some of Their Historical Factors. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2004. Between Secularist Ideology and Desecularizing Reality: The Birth and Growth of Religious Research in Communist China. Sociology of Religion 65: 101–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2005. Lost in the Market, Saved at McDonald’s: Conversion to Christianity in Urban China. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 44: 423–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2006. The Red, Black, and Gray Markets of Religion in China. Sociological Quarterly 47: 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2010. Religion in China under Communism: A Shortage Economy Explanation. Journal of Church and State 52: 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2011. Religion in China: Survival and Revival under Communist Rule. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Fenggang, and Anning Hu. 2012. Mapping Chinese Folk Religion in Mainland China and Taiwan. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 505–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Fuk-tsang. 2009. The Regional Development of Protestant Christianity in China: 1918, 1949 and 2004. China Review 9: 63–97. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Jianrong. 2010. China Underground Church Survey. Available online: http://phtv.ifeng.com/program/shnjd/detail_2010_07/16/1783447_1.shtml (accessed on 12 November 2017).

- Zhang, Jie, and Shenghua Jin. 1996. Determinants of Suicide Ideation: A Comparison of Chinese and American College Students. Adolescence 31: 451–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Jie, and Darwin L. Thomas. 1994. Modernization Theory Revisited: A Cross-Cultural Study of Adolescent Conformity to Significant Others in Mainland China, Taiwan, and the USA. Adolescence 29: 885–903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Jie, and Huilan Xu. 2007. The Effects of Religion, Superstition, and Perceived Gender Inequality on the Degree of Suicide Intent: A Study of Serious Attempters in China. OMEGA Journal of Death and Dying 55: 185–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Jiubo, Xueling Yang, Rong Xiao, Xiaoyuan Zhang, Diane Aguilera, and Jingbo Zhao. 2012. Belief System, Meaningfulness, and Psychopathology Associated with Suicidality among Chinese College Students: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Public Health 12: 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | Furthermore, Tittle and Welch (1983) even found the opposite of what Stark’s moral community thesis posits, although they relied on a proxy measure of aggregate religiosity constructed using individual-level survey data. That is, they reported that the inverse relationship between individual religiosity and self-estimated probability of future deviance was more likely to be significant when the proxy of aggregative religiosity was relatively low rather than high. To explain this unexpected finding, they speculated that religion might have been likely to “distinctly affect conformity only where the larger environment lacks the mechanisms that normally curtail deviance” (Tittle and Welch 1983, p. 674). Yet this finding needs to be interpreted with caution given the limited measurement of two key variables: contextual religiosity and deviance. That is, their measure of context-level religiosity based on the aggregation of individual religiosity may not be necessarily representative of the context, and the behavioral intention of future deviance may not be a good indicator of actual deviance. |

| 2 | This argument may not be that true after 2013 since the government began to have higher restrictions on Christianity and Islam. However, before 2013, folk religions were given less space to develop compared with institutional religions. |

| 3 | We decided not to examine folk religion for two reasons. First and foremost, there are no data available to measure the presence of folk religion at provincial level. Second, based on our previous argument, folk religions are less likely than institutional religions to shape a moral community in secular China for three reasons: (1) folk religions are unlikely to generate a common moral order for individuals because of their numerous gods and deities (Corcoran et al. 2012; Stark 2001); (2) folk religions lack a systematic orthodoxy and structures to constrain individual behaviors (C. K. Yang 1961); and (3) folk religions serve primarily as a utilitarian tool for self-centered and self-serving individuals (Chen 1995; Stark 2001; Wang and Jang 2017). |

| 4 | The link to the website: http://chinadataonline.org/religionexplorer/religion40/#; accessed on 2016-05-20. |

| 5 | Administrative Divisions of People’s Republic of China, from Chinese government website: http://www.gov.cn/test/2005-06/15/content_18253.htm, accessed on May 24th, 2016. |

| 6 | Likewise, 63.3 percent respondents reported that they had never violated government laws, whereas 36.7 percent said that they did rarely (33.2%), sometimes (2.8%), very often (0.4), or always (0.3). Almost 60 percent (58.2%) of respondents reported that they had never violated transportation laws, whereas 41.8 percent said that they did rarely (36.3%), sometimes (3.8%), very often (1.3), or always (0.4). About the same majority (60.4%) reported that they had never violated workplace rules at all, while 35.2, 3.2, 0.7, and 0.5 percent reported they did very rarely, sometimes, very often, and always, respectively. Similarly, 65.5, 31.6, 2.2, 0.3, and 0.3 percent reported that they had never violated organization rules, very rarely, sometimes, very often, or always, respectively. |

| 7 | Respondents affiliated with folk religions are excluded. We also discard observations of Taoism and other religions because of their few observations (N = 22) in GSS2010. |

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Level | |||

| Law violation | 0.318 | 0.466 | 0–1 |

| “Have you ever violated the law?” (1 = yes; 0 = no) | |||

| Government rule violation | 0.377 | 0.485 | 0–1 |

| “Have you ever violated government rules?” (1 = yes; 0 = no) | |||

| Working rule violation | 0.411 | 0.492 | 0–1 |

| “Have you ever violated working rules?” (1 = yes; 0 = no) | |||

| Organization rule violation | 0.357 | 0.479 | 0–1 |

| “Have you ever violated organization rules?” (1 = yes; 0 = no) | |||

| Transportation rule violation | 0.431 | 0.495 | 0–1 |

| “Have you ever violated transportation rules?” (1 = yes; 0 = no) | |||

| 1 = affiliated with Islam, 0 = others | 0.028 | 0.226 | 0–1 |

| 1 = affiliated with Buddhism, 0 = others | 0.054 | 0.164 | 0–1 |

| affiliated with Christianity, 0 = others | 0.025 | 0.155 | 0–1 |

| Ethnicity (1 = non-Han ethnicity; 0 = Han ethnicity) | 0.09 | 0.286 | 0–1 |

| Residence (1 = urban residence; 0 = rural residence) | 0.431 | 0.495 | 0–1 |

| Age (at the year of survey) | 48.838 | 15.497 | 19–98 |

| Female (1 = female; 0 = male) | 0.519 | 0.5 | 0–1 |

| Education (0 = no education; 1 = elementary school; 2 = middle school; 3 = high school; 4 = adult high education; 5 = college education and above) | 1.971 | 1.338 | 0–5 |

| Married (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 0.81 | 0.393 | 0–1 |

| Unemployment (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 0.06 | 0.238 | 0–1 |

| Annual personal income (logged) | 8.037 | 3.184 | 0–14.845 |

| Communist party member (1 = yes; 0 = no) | 0.114 | 0.318 | 0–1 |

| Contextual Level | |||

| Number of mosques per 10,000 people | 0.239 | 1.44 | 0.0003–10.968 |

| Number of temples per 10,000 people | 0.147 | 0.144 | 0.0208–0.546 |

| Number of churches per 10,000 people | 0.141 | 0.195 | 0.001–1.125 |

| Total Population (10,000 people) | 0.032 | 0.02 | 0.001–075 |

| Percent of communist party members | 0.114 | 0.034 | 0.070–0.253 |

| GDP per capita (10,000 RMB ≈ U$1500) | 2.564 | 1.015 | 1.030–4.460 |

| Urbanization rate | 46.873 | 8.687 | 29.890–63.400 |

| Theil index | 0.156 | 0.098 | 0.063–0.489 |

| Illiteracy rate | 7.201 | 3.276 | 3.200–15.940 |

| Percent of minor ethnicity | 8.672 | 12.858 | 0.310–59.430 |

| (1) Violating the Law | (2) Violating Workplace Rules | (3) Violating Government Laws | (4) Violating Organizational Rules | (5) Violating Transportation Laws | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual level | |||||

| Islam | −0.666 * | −0.498 * | −0.435 | −0.781 ** | −0.352 |

| (0.263) | (0.236) | (0.242) | (0.257) | (0.223) | |

| Buddhism | −0.245 * | −0.256 * | −0.292 * | −0.169 | −0.341 ** |

| (0.119) | (0.112) | (0.114) | (0.115) | (0.110) | |

| Christianity | −0.156 | −0.110 | −0.0116 | −0.147 | −0.266 |

| (0.165) | (0.156) | (0.154) | (0.160) | (0.153) | |

| Ethnic minority | 0.481 *** | 0.428 *** | 0.415 *** | 0.447 *** | 0.365 *** |

| (0.107) | (0.107) | (0.105) | (0.108) | (0.104) | |

| Urban resident | −0.208 *** | −0.215 *** | −0.143 * | −0.212 *** | −0.158 ** |

| (0.062) | (0.060) | (0.060) | (0.061) | (0.058) | |

| Age | −0.008 *** | −0.008 *** | −0.010 *** | −0.008 *** | −0.007 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Female | −0.103 | −0.053 | −0.076 | −0.132 * | −0.075 |

| (0.053) | (0.050) | (0.050) | (0.052) | (0.049) | |

| Education | −0.069 * | −0.085 ** | −0.024 | −0.050 | −0.077 ** |

| (0.027) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.025) | |

| Married | −0.034 | −0.088 | −0.094 | −0.070 | −0.108 |

| (0.066) | (0.063) | (0.063) | (0.064) | (0.061) | |

| Unemployment | −0.191 | 0.076 | 0.114 | −0.015 | 0.045 |

| (0.109) | (0.102) | (0.101) | (0.104) | (0.100) | |

| Income(logged) | −0.031 *** | −0.043 *** | −0.034 *** | −0.028 *** | −0.031 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Communist party | −0.238 ** | −0.284 *** | −0.361 *** | −0.398 *** | −0.227 ** |

| (0.089) | (0.083) | (0.084) | (0.087) | (0.080) | |

| Contextual level | |||||

| Number of mosques | −0.155 * | −0.101 | −0.153 ** | −0.094 | −0.099 |

| (0.064) | (0.053) | (0.055) | (0.065) | (0.055) | |

| Number of temples | 0.007 | 0.375 | 0.253 | −0.176 | 0.217 |

| (0.532) | (0.449) | (0.455) | (0.567) | (0.492) | |

| Number of churches | 0.215 | −0.363 | −0.420 | 0.192 | −0.068 |

| (0.779) | (0.655) | (0.664) | (0.826) | (0.714) | |

| Population density | −1.311 | −0.358 | 0.865 | 0.0623 | −3.836 |

| (6.574) | (5.591) | (5.661) | (6.986) | (6.086) | |

| Percent Communist Party members | 2.400 | 2.509 | 2.373 | 2.879 | 2.386 |

| (2.736) | (2.328) | (2.354) | (2.926) | (2.556) | |

| GDP per capita (10,000 RMB) | −0.401 * | −0.347 * | −0.357 * | −0.422 * | −0.157 |

| (0.202) | (0.172) | (0.174) | (0.214) | (0.187) | |

| Urbanization rate | 0.036 | 0.024 | 0.036 | 0.034 | −0.002 |

| (0.028) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.030) | (0.026) | |

| Theil index | −0.239 | 0.268 | 0.151 | −0.233 | 1.221 |

| (1.169) | (0.992) | (1.003) | (1.246) | (1.085) | |

| Illiteracy rate | −0.050 | −0.034 | −0.025 | −0.046 | −0.046 |

| (0.038) | (0.032) | (0.032) | (0.040) | (0.035) | |

| Percent of ethnic minority | 0.002 | −0.000 | 0.004 | −0.002 | 0.001 |

| (0.008) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.007) | |

| Intercept | −0.400 | 0.401 | −0.493 | −0.156 | 1.135 |

| (1.114) | (0.945) | (0.958) | (1.184) | (1.033) | |

| ICC | 3.43% | 2.42% | 2.48% | 4.01% | 3.05% |

| (1) Violating the Law | (2) Violating Workplace Rules | (3) Violating Government Laws | (4) Violating Organizational Rules | (5) Violating Transportation Laws | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual level | |||||

| Islam (A) | −0.904 ** | −0.677 ** | −0.686 * | −1.000 *** | −0.354 |

| (0.292) | (0.260) | (0.267) | (0.286) | (0.243) | |

| Buddhism (B) | −0.263 | −0.368 * | −0.402 ** | −0.111 | −0.442 ** |

| (0.159) | (0.149) | (0.151) | (0.151) | (0.146) | |

| Christianity (C) | −0.418 | −0.144 | −0.213 | −0.388 | −0.276 |

| (0.278) | (0.260) | (0.257) | (0.271) | (0.254) | |

| Ethnic minority | 0.483 *** | 0.429 *** | 0.414 *** | 0.452 *** | 0.364 *** |

| (0.107) | (0.107) | (0.106) | (0.108) | (0.104) | |

| Urban resident | −0.207 *** | −0.214 *** | −0.142 * | −0.210 *** | −0.159 ** |

| (0.062) | (0.060) | (0.060) | (0.061) | (0.058) | |

| Age | −0.008 *** | −0.008 *** | −0.010 *** | −0.008 *** | −0.007 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.001) | |

| Female | −0.102 | −0.0515 | −0.0742 | −0.131 * | −0.074 |

| (0.053) | (0.050) | (0.050) | (0.052) | (0.049) | |

| Education | −0.067 * | −0.084 ** | −0.022 | −0.049 | −0.078 ** |

| (0.027) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.025) | |

| Married | −0.033 | −0.088 | −0.093 | −0.070 | −0.108 |

| (0.066) | (0.063) | (0.063) | (0.064) | (0.061) | |

| Unemployment | −0.193 | 0.076 | 0.112 | −0.015 | 0.044 |

| (0.109) | (0.102) | (0.101) | (0.104) | (0.100) | |

| Income(logged) | −0.030 *** | −0.043 *** | −0.034 *** | −0.028 *** | −0.031 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Communist party | −0.236 ** | −0.282 *** | −0.359 *** | −0.395 *** | −0.227 ** |

| (0.089) | (0.083) | (0.084) | (0.087) | (0.080) | |

| Contextual level | |||||

| Rate of mosques (D) | −0.609 * | −0.219 * | −0.543 ** | −0.320 | −0.100 |

| (0.263) | (0.0940) | (0.204) | (0.168) | (0.0677) | |

| Rate of temples (E) | 0.420 | 0.451 | 0.580 | 0.0423 | 0.191 |

| (0.502) | (0.430) | (0.426) | (0.535) | (0.492) | |

| Rate of churches (F) | −0.430 | −0.529 | −0.972 | −0.117 | −0.089 |

| (0.738) | (0.626) | (0.618) | (0.780) | (0.713) | |

| Total population | −3.589 | −0.978 | −1.173 | −1.266 | −3.833 |

| (5.613) | (5.293) | (4.892) | (6.408) | (6.067) | |

| Percent of Communist Party member | 3.610 | 2.831 | 3.397 | 3.524 | 2.394 |

| (2.337) | (2.199) | (2.029) | (2.682) | (2.548) | |

| GDP per capita (10,000 RMB) | −0.410 * | −0.350 * | −0.366 * | −0.418 * | −0.160 |

| (0.169) | (0.163) | (0.148) | (0.195) | (0.186) | |

| Urbanization rate | 0.038 | 0.025 | 0.039 | 0.034 | −0.002 |

| (0.023) | (0.022) | (0.020) | (0.027) | (0.026) | |

| Theil index | −0.146 | 0.332 | 0.253 | −0.160 | 1.233 |

| (0.965) | (0.933) | (0.841) | (1.128) | (1.081) | |

| Illiteracy rate | −0.025 | −0.028 | −0.0036 | −0.034 | −0.045 |

| (0.034) | (0.030) | (0.029) | (0.037) | (0.035) | |

| Percent of ethnic minority | −0.000 | −0.001 | 0.002 | −0.004 | 0.001 |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Cross-level Interaction | |||||

| A × D | 0.505 | 0.155 | 0.441* | 0.272 | 0.00189 |

| (0.269) | (0.094) | (0.209) | (0.168) | (0.058) | |

| B × E | 0.091 | 0.538 | 0.525 | −0.284 | 0.471 |

| (0.504) | (0.463) | (0.459) | (0.499) | (0.445) | |

| C × F | 1.413 | 0.197 | 1.117 | 1.318 | 0.055 |

| (1.171) | (1.171) | (1.113) | (1.168) | (1.128) | |

| Intercept | −0.681 | 0.342 | −0.724 | −0.261 | 1.129 |

| (0.943) | (0.892) | (0.819) | (1.078) | (1.029) | |

| ICC | 2.17% | 2.09% | 1.60% | 3.21% | 3.02% |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Jang, S.J. The Effects of Provincial and Individual Religiosity on Deviance in China: A Multilevel Modeling Test of the Moral Community Thesis. Religions 2018, 9, 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9070202

Wang X, Jang SJ. The Effects of Provincial and Individual Religiosity on Deviance in China: A Multilevel Modeling Test of the Moral Community Thesis. Religions. 2018; 9(7):202. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9070202

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiuhua, and Sung Joon Jang. 2018. "The Effects of Provincial and Individual Religiosity on Deviance in China: A Multilevel Modeling Test of the Moral Community Thesis" Religions 9, no. 7: 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9070202

APA StyleWang, X., & Jang, S. J. (2018). The Effects of Provincial and Individual Religiosity on Deviance in China: A Multilevel Modeling Test of the Moral Community Thesis. Religions, 9(7), 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9070202