Abstract

Moral decision making systems have long been a popular and widely discussed part of computer games; especially in—but not limited to—role-playing games and other games with strong narrative elements. In this article, an attempt will be made to draw a connection between historic and recent concepts of karma and moral decision making systems in digital games, called ‘karma systems’. At the same time, a detailed analysis of one such system (that of Mass Effect 2) will be provided.

1. Introduction

In the recent past, research in religious studies into digital games has experienced an enormous upswing. The topic has come into the focus of academic online journals such as Gamevironments1, Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet2 and, not least through this issue of Religions. In addition, there has been a large increase in anthologies (cf. e.g., Cheruvallil-Contractor and Shakkour 2015; Šisler et al. 2018) and monographs (cf. e.g., Steffen 2017) dealing with religion and digital games in terms of content, theory, and methodology. Coupled with an equally growing public interest in religious (and generally cultural) aspects of games, this paints a thoroughly positive picture.

This article is intended to contribute to the growing scientific discussion about digital games. For this, an orientation was chosen which, to a certain extent, forms a unique selling point of the medium of ‘games’ but, on the other hand, is still rather underrepresented in the scientific debate to date.

In Theorizing Religion in Digital Games. Perspectives and Approaches, a framework for the identification and investigation of religious elements in digital games was presented. Besides religious influences in narratives and aesthetics, the aspect of gameplay was also highlighted (Heidbrink et al. 2014, pp. 32–35). Regarding the topic of agency and interaction, the approach closely followed Espen Aarseth’s concept of “ergodic action”:

The concept of cybertext focuses on the mechanical organization of the text, by positing the intricacies of the medium as an integral part of the literary exchange. However, it also centers attention on the consumer, or user, of the text, as a more integrated figure than even reader-response theorists would claim. The performance of their reader takes place all in his head, while the user of cybertext also performs in an extranoematic sense. During the cybertextual process, the user will have effectuated a semiotic sequence, and this selective movement is a work of physical construction that the various concepts of “reading” do not account for. This phenomenon I call ergodic, using a term appropriated from physics that derives from the Greek words ergon and hodos, meaning “work” and “path”. In ergodic literature, nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text.(Aarseth 1997, p. 1)

In order to do justice to this “ergodic” element, it is necessary to investigate those aspects of a game that make this element possible in the first place: game mechanics3 and game rules. For this article, the choice fell on moral decision making systems which combine various differing game mechanics and rules and also usually integrate with a game’s aesthetics and narrative. In particular, the focus will be on point based systems and their reception. These special forms of moral decision making systems are interesting, among other things, because in online discussions and on popular gaming websites they are often called ‘karma systems’ (or variations of it such as ‘karma meter’4 etc.).

The aim of this article is therefore to draw a connection between these ‘karma systems’ and common ideas and concepts of the religious concept of karma and to examine them for possible interactions and attributions of meaning. In addition, the detailed content analysis of a single ‘karma system’ (that of Mass Effect 2) and the associated actor perspectives are intended to illustrate the complexity of the design, reception, and negotiation processes associated with a modern computer games.

In order to achieve this, a historical analysis of the public and academic reception of the concept of karma will be carried out in the following chapter. Subsequently, an attempt will be made to create a definition of ‘karma systems’ in games using some examples from popular games. Finally, a detailed content analysis of the karma system of Mass Effect 2 and a discussion of the associated design processes (intertextual and intermedial, as well as economic influences) and reception by the players will be conducted5.

2. Public and Academic Reception of the Concept ‘Karma’

2.1. History of Reception

In the following, an attempt will be made to trace the term karma and its manifold interpretations through history. For this purpose, the method of reception history analysis was chosen.

“History of reception” should be understood in the context of Hans Robert Jauß, Wolfgang Iser and—for the context of religious studies of particular importance—Michael Staußberg.

Jauß describes the concept of the history of reception (or aesthetics of reception) in his book Die Theorie der Rezeption, published in 1987, as follows:

It calls for the history of literature and the arts to be understood now as a process of aesthetic communication in which the three instances of author, work and recipient [...] are equally involved. This included finally inserting the recipient as recipient and mediator, thus as carrier of all aesthetic culture, into his historical right [...].(Jauß and Sund 1987, p. 5)

He is committed to involving the reader and not only—as had been customary in literary studies up until then—the author of a text in his or her investigation. By looking at the reader, the “recipient” of the text, the eye for the multitude of processes of communication and interpretation, which, as Wolfgang Iser puts it, constitute the “act of reading”, is sharpened (Iser 1994). The focus here should no longer be on a single historically and socially universal “correct” interpretation of a text. Rather, it is about the context in which a text was and is written and read (Jauß 1994, p. 136).

Michael Stausberg tried to adapt and expand this methodology for religious studies in his book Faszination Zarathustra:

This seemingly banal hermeneutic starting point has serious consequences—also for religious studies, since in this way, for example, the usual representation of ‘the doctrine’ or ‘the message’ of a certain religion or a certain text is undermined. The historically working religious studies would thus not so much have the task of systematizing the theology or mythology of a religion from the multitude of sources, but to present religious history as a concatenation of the productive reception and selection achievements of certain motives, themes, concepts, or texts brought about by followers of certain religions in certain historical situations, whereby the historian must take into account his own starting point, which is determined by the history of research to date, among other things6.(Stausberg 1998, p. 3)

He thus takes over the involvement of the “reader” demanded by Jauß and Iser. However, the term is not really accurate in the context of Stausberg’s approach, since it goes beyond the purely literary or text-analytical approach and also addresses other objects of investigation. The concept of the actor or the “recipient” is probably more appropriate here (Stausberg 1998, p. 3).

The following examination of the historical reception of the concept of karma will be closely oriented to the principles presented here. For the purpose of clarity, it was necessary to make certain classifications, each of which should allow a rough allocation of certain ideas of karma. However, these should under no circumstances be understood as an immovable, ‘hard’ distinction between the various interpretations. Likewise, the chronological order of the individual sections should not be confused with the statement that this is a strictly linear ‘evolution’ of the karma term, in which one interpretation ‘replaces’ another. Although some developments can be observed, they are anything but linear and can also run parallel or contrary to further processes of interpretation and negotiation. Moreover, it is also quite possible that apparently separate lines of reception, which originate from the same ‘origin’, meet and influence each other again in the course of these processes. A ‘timeline’ of karma ideas is neither possible nor intended here. Rather, an attempt is made to shed light on as many lines of reception as possible, their roots, influences among themselves and through various religious and philosophical traditions, without judging by ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ interpretations.

2.2. ‘Traditional Karma’?

Despite all ambiguity, in describing the term ‘karma’, it is appropriate to start where the concept has its origin in both the popular and the academic view: the South Asian religious traditions. In this more or less ‘geographical’ classification, however, the similarities between popular and scientific discussion often end.

So what is understood by the public as “traditional karma”? The Encyclopedia Britannica provides the following explanation:

Karma, Sanskrit karman (“act”), Pali kamma, in Indian religion and philosophy, the universal causal law by which good or bad actions determine the future modes of an individual’s existence. Karma represents the ethical dimension of the process of rebirth (samsara), belief in which is generally shared among the religious traditions of India. Indian soteriologies (theories of salvation) posit that future births and life situations will be conditioned by actions performed during one’s present life—which itself has been conditioned by the accumulated effects of actions performed in previous lives. The doctrine of karma thus directs adherents of Indian religions toward their common goal: release (moksha) from the cycle of birth and death. Karma thus serves two main functions within Indian moral philosophy: it provides the major motivation to live a moral life, and it serves as the primary explanation of the existence of evil7.

Axel Michaels sums up this idea in his review of Wilhelm Halbfass’ book Karma und Wiedergeburt im indischen Denken (cf. Halbfass 2000):

The ideas that are generally linked to this concept are truly radical: every act, whether culpable or meritorious, is charged for future existence, all actions appear causally in the balance of posthumous retributions. The omnipotence of the gods is limited, man has his fate in his own hands. Moreover, every action is karmically stressful and leads to a new life of suffering. In the end, only inaction and the search for salvation will help.(Michaels 2001)

He criticizes, in his view, “simplified” views of the concept of karma for drawing a “lethargic and apathetic” picture of the Indians who “can remain in their caste destiny or go into secular asceticism” (Michaels 2001). He rejects any kind of reduction of “karma” both to an inevitable “destiny”, into which one has to submit powerlessly, and to complete self-determination:

In India, man is not the plaything of a god, but also not the unrestricted master of his own life. So it is too easy to confront the omnipotence of God in Christianity with the omnipotence of self in Hinduism. Nevertheless, divergences remain. Above all these: here the requirement of a probation in life, there the desire for liberation from life. Rebirth is not a reward in most Indian liberation teachings, but punishment or a necessary evil.(Michaels 2001)

When looking at karma, Wilhelm Halbfass himself also refers to its concrete meaningful function:

It provides a framework and guideline for moral and religious orientation by ascribing to current actions and decisions an inherent power to trigger future and punishable consequences.(Halbfass 2000, p. 210)

At the same time, however, Halbfass warns several times against talking about “the law of karma” (Halbfass 2000, pp. 31, 310). Axel Michaels joins this position:

There are texts in which such causal relationships are established. They say, for example: He who commits adultery becomes sterile in the next life; he who eats flesh gets red limbs; he who drinks alcohol, black teeth. Nevertheless, such registers are to be seen only as rules, but not as a mechanism of the consequences of the crime, as Max Weber, who called the karmal doctrine the “most perfect solution to the problem of theodicy”, still assumed.(Michaels 2001)

In his article Reinkarnationsvorstellungen als Gegenstand der Religionswissenschaft und Theologie, Michael Bergunder also addresses the concrete social benefits of karma concepts by, among other things, identifying them as justification for the “social norms of a society structured according to socio-religious hierarchies […] as it corresponds to the Brahman ideal” (Bergunder 2001, p. 707). Here, therefore, an authoritative and legitimatory aspect is also gaining in importance.

However, Bergunder also warns against limiting karma concepts to this aspect and also problematizes the central role attributed to them in Hindu traditions. Although at the beginning he himself refers to the close connection between “karmal doctrine” and rebirth (Bergunder 2001) he goes on in declaring that “in authoritative Hindu movements the karma rule is negated or deprived of its validity” (Bergunder 2001, p. 708). As an indication of this, he uses what he calls “popular Hinduism”, for which he postulates that “concrete cases of reincarnation [are] an exceptional phenomenon” and “Karma conceptions [...] would usually have no relation to rebirth“ (Bergunder 2001, p. 709). What exactly Bergunder understands by this “popular Hinduism”, he unfortunately does not explain more precisely, but instead the use of the karma term. According to Bergunder, karma is understood here as “a kind of synecdoche for the destiny decreed by God”, which “[is] used to explain accidents”, but […] usually resigns behind other explanations” (Bergunder 2001).

Already at this first glance at the interpretation of the karma concept, exemplarily carried out in the context of Hindu religious traditions, it becomes apparent that several views have formed on its ‘true’ meaning. The popular Western interpretations are in conflict with contemporary and ‘classical’ scientific approaches, as well as what Bergunder calls “popular Hinduism”. This description is, of course, far from exhaustive, but should already show that, despite the fact that it has already been limited to a regional framework, a generally accepted definition of karma cannot be found even where its historical origin is traditionally located. Instead of continuing (in vain) to search for such a general definition, the following representations of further karma understandings will attempt to explain how this multitude of frequently contradictory interpretations and interpretations arose. It should also be made clear how past discourses, both popular and scientific, can influence current discourses.

2.3. Karma, Neo-Hinduism, and the Theosophical Society

From the second half of the 19th century onwards, the so-called Theosophical Society around Helena Blavatsky played a prominent role in the development of the karma concept prevailing. However, in order to explain their influence, it is necessary to first take a look at the image that still prevailed in Western research and mission literature at that time with regard to karma concepts. Michael Bergunder writes about this:

Herder already states that the doctrine of reincarnation is the “opium” that enables the Indians to live in quiet passivity and in acceptance of the strict caste hierarchies. In the following period this thesis formed an independent topos both in orientalist research and in Christian missionary literature, and Max Weber still speaks of the “ingenious combination of caste legitimacy and karmal doctrine”, which is “connected to the real social order through the promises of rebirth”, “the fixed scheme” which legitimizes a rigid and not dynamic caste society.(Bergunder 2001, p. 711 )

In the middle of the 19th century, a reform movement was created, which Bergunder calls “neo-Hinduism”. The latter immediately set about presenting alternative approaches to the karma concept, which were supposed to put it in a better light:

The beginning of this Hindu reconsideration is marked by Bankimchandra Chattopadhayay, who in his Bengali Bhagavadgita commentary, under sharp criticism of Christian concepts of the hereafter, defends the doctrine of karma and rebirth, although scientifically neither provable nor refutable, as logical and ethically reasonable.(Bergunder 2001, p. 712)

Bergunder sees here in reference to Halbfass an Indian attempt to assert oneself against the West by counteracting the image of karma as the “opium” of what Michael also calls a “lethargic and apathetic” society (Michaels 2001). Another important aspect of this “reinterpretation” is the generally positive representation of karma, which now focuses on the personal spiritual development of the individual over several lives. Bergunder also refers here to Aurobindo Ghose, for whom “the karmic process [is] an evolutionary, cosmic self-development of the mind to a higher consciousness force, which is supramental consciousness” (Bergunder 2001, p. 712).

It is no coincidence that a strong concentration on “self” and “personal development” can be seen here. These schools of thought were also significantly influenced by the criticism of institutionalized religion that emerged in the West at that time. Robert Sharf speaks here of the “nineteenth-century European Zeitgeist”, which is a legacy of “anti-clericism and anti-ritualism of the Reformation, the rationalism and empiricism of the Enlightenment, the romanticism of figures such as Schleiermacher and Dilthey, and the existentialism of Nietzsche” (Sharf 1995, p. 247). Although Sharf refers specifically to the role of meditative practice and experience in Buddhist reform movements in Japan and Southeast Asia with regard to the influence of this “zeitgeist”, elements of it can also be recognized in the case of the “neo-Hinduist” reform movements. An example of this would be the urge for rationalism that is evident in the Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay already mentioned above. In integrating these Western patterns of thought into one’s own religion, Sharf believes he sees a typical reaction to the ongoing contact with Western culture, science, and philosophy. He attests the Buddhist reform movements a strong tendency to emphasize “private spiritual experience” in response to this contact and the subsequent “cultural relativism”. According to him, this was designed transhistorically and transculturally in order to immunize against relativistic criticism (Sharf 1995, p. 268).

In the context of “neo-Hinduist” reform efforts around the concepts of karma and rebirth, overlaps can be observed. Thus, in the central role of the “self” in the “evolutionary” process of self-development, a strong reference to individual experience, detached from institutionalized religion, can also be recognized. However, the term “evolutionary” already reveals another strategy that deviates from Sharf’s thesis. In addition, an attempt was made to bring karma and rebirth to a “rational”, scientifically explainable level, for example by referring to “causality”, i.e., the scientifically provable relationship of “cause and effect”.

Although, as Bergunder also notes, the central role of karma and rebirth cannot be determined in all currents of “Neohinduism”, this interpretation nevertheless exerted a strong influence, among others also in later Western interpretations. The main reason for this was the influence of the so-called Theosophical Society.

The Theosophical Society was founded in New York in 1875 by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott. The society was founded on the conviction that there was a “true core” in all religions and the aim was therefore to establish a “universal brotherhood” uniting all people. At the time of its foundation, the society was marked by European “esoteric” and “mystical” traditions, which changed with the relocation of both Blavatsky and Olcott to India. The “idea” of, as Bergunder puts it, “esoterically understood unity of all religions” (Bergunder 2001, p. 714) led Blavatsky and her followers—soon also among the Indian population—to integrate elements of Indian religious traditions into their own teachings, including the karma concept. According to the doctrine of an “all-encompassing brotherhood of humanity”, however, the role of the individual in determining his own destiny was reduced. Karma became a judging power, which in its influence on mankind rather fulfils “instructive” functions:

[…] it is the power that controls all things, the resultant of moral action, the metaphysical Samskāra, or the moral effect of an act committed for the attainment of something which gratifies a personal desire. There is the karma of merit and the karma of demerit. Karma neither punishes nor rewards, it is simply the one Universal Law which guides unerringly, and, so to say, blindly, all other laws productive of certain effects along the grooves of their respective causations.(Blavatsky and Mead 2003, p. 161)

So the responsibility of the individual lies only in deciding whether he voluntarily accepts the “teaching” of karma without its help, or “learns” from it; he has no influence on the “law of karma” itself. At this point the theosophical doctrine strongly reminds us of certain elements of Christian moral doctrine, which put man before the decision to attempt to fathom moral values through his own experience and reflection, or to find their “clear” form in the form of God’s revelation (e.g., cf. Hörmann 1969, p. 602). This similarity with Christian teachings is not surprising considering that the Western esoteric origin of theosophical teaching was also strongly influenced by concepts of Emanuel Swedenborg’s “Christian theosophy” and other Christian mystical traditions (e.g., cf. Swedenborg 1880).

The concept of karma is thus expanded to include a strong moral core whose basic ethical guidelines can only be fathomed by the individual, but cannot be influenced. This view can also be found in later interpretations within theosophical circles; even after the dissolution of the Theosophical Society into numerous smaller groups after Helena Blavatsky’s death in 1891, karma in the Theosophischen Pfad from 1912 is also called “divine law”:

Karma is the law that ensures that all things serve those who love God, that is, mankind, for the best. How clearly and forcefully history teaches us that blessed work of the Law![…]Karma, the lot given to us, is the will of the divine soul in us, and when we get used to looking at life with its vicissitudes and apparent contradictions from the standpoint of the law of brotherhood, then we gain another, deeper concept of good and evil and accept the judgment of the law as our own divine will.(Karma im Lichte der Geschichte 1912, pp. 304–5)

The process of this “teaching” through karma is described as “evolutionary” and continues through several incarnations, whereby the “personality” does not persist, but rather the “Ego”:

Only that which is immortal in its very nature and divine in its essence, namely, the Ego, can exist forever. And as it is that Ego which chooses the personality it will inform, after each Devachan, and which receives through these personalities the effects of the Karmic causes produced, it is therefore the Ego, that self which is the “moral kernel” referred to and embodied karma, “which alone survives death”.(Blavatsky and Mead 2003, pp. 161–62)

At this point at the latest, strong points of intersection with approaches of “neo-Hinduism” become clear. The immortal, existential “Ego” that survives the personality and is part of an evolutionary learning process strongly recalls that “evolutionary, cosmic self-development of the mind to a higher consciousness, the supramental consciousness”, as Bergunder puts it with reference to Aurobindo (Bergunder 2001, p. 713). Here you can see the influence of both currents on each other, to which Bergunder also refers (Bergunder 2001, p. 712).

Another overlap with “neo-Hinduist” approaches, which survived the end of the original society, is found in the alleged “scientificness” of theosophical doctrine of karma. The Theosophical Forum of 1930 calls karma “a far-reaching application of well-known basic scientific teachings of the law of cause and effect […] and its work is therefore such of error-free justice”. (Beale et al. 1930, p. 18)

The fact that the Theosophical Society and many of its daughter and subgroups lost much of their direct influence in the 20th century did not change the fact that their teachings can still be found in popular ideas of karma today. However, this wide spread was only made possible with the emergence of what is today strongly generalized as the ‘New Age movement’.

2.4. Karma and the New Age Movement

Since this section deals with the role of the so-called ‘New Age movement’ in the spread of karma ideas, it is appropriate to briefly problematize the term ‘New Age movement’ itself. In fact, the term ‘New Age movement’ is an artificial construct trying to make a multitude of movements, single currents and groupings tangible. George Chryssides sums up the problem of such an overarching concept:

A further problem relates to the supposed constituents of the New Age. If it supposedly includes homeopathy, eastern religions, ley lines, deep ecology, angels, channeling, Tarot cards, astrology and Neuro-Linguistic Programming, what do such interests have in common? If there is no common essence, do they at least have a relationship? If they have common or related features, what is the point in conjuring up a term to refer to them collectively?(Chryssides 2007, p. 6 )

It is not the intention of this paper to answer these questions. Rather, as the term continues to be used, we should be aware that it is not a single movement, but rather a makeshift umbrella term for what Chryssides calls a “counter-cultural zeitgeist” (Chryssides 2007, p. 22), which is only used in the absence of suitable alternatives.

So far, much has been written about the interpretation processes that took place within the narrow circles of the Theosophists and also within the Indian society. However, it should be noted that despite its popularity, the Theosophical Society addressed only a relatively small elite circle of scientists and intellectuals. It was not until the middle of the 20th century that the teachings of Theosophy reached a broad audience.

After Helena Blavatsky’s death in 1891, the Theosophical Society fragmented into a multitude of smaller groups, which, however, were still close to the original theosophical teachings and thus kept them alive. As a result, concepts of karma, reincarnation, meditation, and many other apparently Indian religious concepts encountered the generation of “Baby Boomers” and the emerging ‘New Age movement’ in the mid-20th century.

At that time, after the Second World War, North America was in an economic upswing that brought the American middle class in particular a great deal of prosperity and financial security. Due to a new idealization of family life, there was an enormous increase in births in the USA.

While a similar increase in the birth rate in Europe was already over after five years, it only reached its peak in the USA in 1957 and ended in 1965: Susan Love Brown identifies the children of that time, who grew up well-protected in this prosperity and this feeling of security, in her article Baby Boomers, American Character and the New Age as one of the germ cells of the ‘New Age movement’, which at that time was rapidly gaining supporters (Brown 1992).

The influence of the “Baby Boomer Generation”, as Brown calls it, on the emergence of the ‘New Age movement’ is explained by the social circumstances of that time. Compared to the direct predecessor generations, children of the new generation experienced much greater prosperity, were for the first time under the influence of television on a large scale and were better educated. The enormous number of births made the USA a country in which children were at the center. This general social prosperity led to a new orientation of the members of this generation away from the problems of their parents, to problems that were more oriented towards their own age group, especially because not only the parents were the only effective force for socialization, but also the mass media gained more and more importance. This in turn led to the members of this generation rebelling against their parents as they slowly grew up during the 1960s. This rebellion was based on an idealistic view of how society should be. There was no rebellion against the general values of the parents, but against the hypocrisy behind them.

Brown identifies the main characteristic of the “New Age” as a new orientation towards “self” and “experience”. She explains this orientation through the wide spread of drugs in America in the 1960s. According to her, the use of drugs led many to want to explore even further the new levels of consciousness they had learned, which in turn led to interest in mysticism and Eastern religions. She uses statistics that show that “[....] 96.4 percent of those people living in communities based on eastern ideologies had used drugs before joining, compared to 56.2 percent of people joining christian communities” (Brown 1992, p. 95). In their search for “new” and “exotic” religious experiences, the followers of the “New Age” naturally also came across the teachings of Theosophy and its daughter groups. Some authors, such as Chryssides, address the influence of the Theosophical Society on the ‘New Age movement’ even earlier and more centrally:

Although the Theosophical Society is not normally considered to be part of the New Age Movement, its eclectic ideas have significantly contributed to the development of the New Age phenomenon. In particular, Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), Alice Bailey (1880–1949), Juddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986), and Dion Fortune (1890–1946), all of whose writings still feature significantly on the Mind-Body-Spirit shelves of bookshops, were at one time Theosophists, although all except Fortune abandoned the Theosophical Society.(Chryssides 2007, p. 6)

In addition, many followers of the ‘New Age’ began to travel to India to learn directly from Indian ‘masters’ and ‘gurus’. Of course, they also met representatives of those Hindu reform movements that had formed under the influence of the Theosophical Society in the 19th century. They had discovered their great opportunity here to make their own concepts more widely known in the West, which was, of course, followed by commercial interests.

This influence and fascination with Far Eastern religious traditions in general ultimately led to an enormous popularization of them, including, of course, the doctrine of karma, which placed so much emphasis on individual decision-making power over personal destiny. The final impetus for the establishment of the term karma in Western society was provided by the commercialization of the ‘New Age movement’ from the early 1980s. Media, publishers, but also former convinced representatives of the ‘New Age’ itself recognized the enormous commercial potential behind its manifold theories and practices. And so bookshops soon filled shelves with works on meditation, holistic healing practices, channeling, and much more. The commercial power of karma was also discovered in this way, so it comes as no surprise that booksellers still today have an extensive range of books such as Karma in Practice. Shaping the Future8 or Karma—The Instructions for Use: … so That Fate Does What You Want9. The concrete interpretation of the karma concept—as the titles of the books mentioned here also implies—is very ‘practical’. Karma is often traced back to Far Eastern religious traditions, but the applicability of the concept is also promoted beyond religious practice, since the law of ‘cause and effect’ is after all a ‘rational’ principle.

2.5. Interim Conclusion

So what is karma? The term is widely known today, due to its popularization during the ‘New Age movement’ and beyond. A clear meaning cannot be determined, however, because even if a very simplified image of karma currently prevails in the general public, which is roughly associated with Indian religious traditions and at the center of which is the ‘rationally’ comprehensible law of ‘cause and effect’, this interpretation is naturally not the only one. ‘Traditional’ interpretations can be found as well as a multitude of interpretations that can be traced back to theosophical or ‘neo-Hinduist’ sources and also bring with them strong moralizing aspects—each of course again dependent on the contemporary discourse on morality and ethics. Of course, none of these interpretations should be considered ‘wrong’ or ‘right’, even if they contradict each other. Ultimately, the definition used depends on individual ideas, preferences and living conditions, the ‘recipients’; and of course—and this should not be forgotten in times of mass media and the Internet—from where they get them.

The film and television industries have also discovered the concept of karma for themselves. How ambivalent the term is often used, however, can be well illustrated by a quotation from the well-known film Ghostbusters from 1984 by Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis. When at the beginning of the film the three main characters Dr. Peter Venkman, Dr. Raymond Stantz, and Dr. Egon Spengler are expelled from the university because of the dubious nature of their research, Peter Venkman (played by Bill Murray) comments as follows:

For whatever reasons, Ray, call it fate, call it luck, call it karma. I believe everything happens for a reason. I believe that we were destined to get thrown out of this dump.(transcribed from Aykroyd and Ramis (1984))

For a religious studies view, especially in the context of the analysis of the ‘karma system’ of Mass Effect 2 sought in this paper, this means that the results of the analysis carried out must not be compared with a single idea of karma—whether it be a supposedly ‘present’ or ‘traditional’. Rather, all the ideas presented here must be taken into account, as well as the possibility that even the implementation of a ‘karma system’ into a game and the reception of this system by the players can again lead to new interpretations and negotiations of meaning of the concept karma.

Before a specific ‘karma system’, namely that of Mass Effect 2, is dealt with in detail in Section 4, in the following chapter a useful definition of the term itself and a basis for the comparison of different ‘karma systems’ will be created using two popular examples: Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic and Fallout 3.

3. Karma Systems in Games

It is difficult to describe what constitutes a ‘karma system’ without falling into criminal generalizations, because like so much that falls into the realm of ‘new media’, computer games—and with them the systems which define them—have developed rapidly over the last two decades. Moral decision making systems are not exempt from this and have been subjected to a constant process of development, which naturally always took place in the context of related games, which implemented a similar system earlier or even at the same time.

Nevertheless, in the following chapter an attempt we will be made to identify some elements that most so-called ‘karma systems’ have in common in order to provide a definition that can be used at least for this paper. This definition is to be worked out on the basis of two exemplary games whose moral decision making systems are called ‘karma systems’ by players—just like the moral decision making system of Mass Effect 2.

3.1. A Brief History of Karma Systems

The games with ‘karma systems’ presented below were selected primarily from the ranks of commercially successful games of the last 15 years. The main criteria were a verifiable connection to Mass Effect 2—for example via its developer studio Bioware—or a relatively close release in order to make possible demarcation processes understandable, as well as a connection with “karma systems” in relevant articles in the gaming press and/or discussions by players. The latter is particularly important, since “karma system” and related terms referring to “karma” are primarily coined by the gaming press and players themselves.

The games featured here are Bioware’s Star Wars—Knights often the Old Republic (KotOR) and Fallout 3 from Bethesda Game Studios.

KotOR was chosen because it was created by Bioware, the developer of Mass Effect 2, and was also under the same Game Director or Executive Producer, Casey Hudson. The moral system of KotOR is regarded by players and gaming press as the spiritual forefather of the “karma system” of Mass Effect 2.

Fallout 3, on the other hand, is the work of a development studio competing with Bioware and, like Mass Effect 2, is a relatively current example of the implementation of a “karma system”. Fallout 3 also has a special role to play, as it is the only game that, has a “karma system” that actually uses the term “karma” within the game. What this can mean, however, will be clarified later.

The presentation of the games will initially be largely descriptive, in order to lay the informative foundation for a more detailed analysis of the respective connections to Mass Effect 2 in Section 4. Subsequently, an attempt will be made to find a useful definition for the “karma systems” examined here.

3.2. Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic

Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic was first released on 15 July 2003 for Xbox and 19 November 2003 for PC. Knights the Old Republic was developed by Bioware and distributed by LucasArts.

The game was a great commercial success. Four days after the release, 250,000 copies had already been sold and the international average scores amount to 93 out of 100 possible points10.

As the title of the game suggests, it is located in the Star Wars universe based on George Lucas’ films. In fact, some game elements here are based on the Star Wars Role Playing Game, a ‘pen and paper’ role-playing game by Bill Slavicsek, Andy Collins, and JD Wiker, which in turn is based on the third edition of Advanced Dungeons and Dragons. The technology is based on the Aurora Engine developed by Bioware itself.

The ‘karma system’ of Knights often the Old Republic is strongly influenced by the ‘mythology’ of the Star Wars universe and its pronounced conflict between the ‘good’ Jedi and the ‘evil’ Sith. The player is often faced with the choice of pursuing one of two possible solutions in quests and dialogues. A ‘neutral’ solution is usually not intended. For example, the player can choose to defend a village from a group of bandits or ally with them and take a share of the loot.

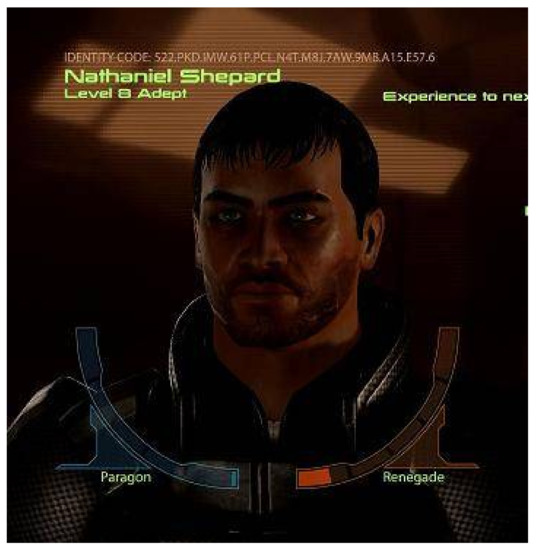

The decision is then evaluated by the game and is reflected in a scale that can be viewed at any time and ranges from ‘Dark’ to ‘Light’ (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

“Alignment” Bar11.

The character shown here has reached a maximum of “dark force points”, whereby it should be noted that with the collection of enough points contrary to the current attitude a “change of opinion” is still possible in the later course of the game. You can see the red fog in the background, which changes its color from red (evil) to blue (good) depending on the orientation of the character. In the player portrait in the lower right corner of the picture you can also see the physical change that the character undergoes depending on his or her orientation. The stronger this tends to the “dark side of the force”, the paler the skin and the eyes get a sickly red coloration.

Additionally, depending on which side the player chooses, he has access to different special skills that are only available to either the “light” or the “dark” side of the Force. The “dark”’ powers focus primarily on inflicting damage (e.g., indicated by the “+1-8 DAM” above the character portrait in Figure 1), while the “light” powers focus on healing and support.

All these elements can be easily traced back to the Star Wars canon. The colors red and blue are found in the lightsabers wielded by Luke Skywalker, the hero of the trilogy and his teacher Obi Wan Kenobi, and Darth Vader, the villain of the films. The physical effects of the use of the “dark side” and its exclusive powers can also be found in the films and other sources belonging to the canon.

3.3. Fallout 3

Fallout 3 was first released on 28 October 2008 and was developed by Bethesda Game Studios. Bethesda Softworks and ZeniMax Media were responsible for distribution.

The two previous parts of the Fallout series had been developed by Black Isle Studios, which had supported Bioware in the development of the Baldur’s Gate games. Initially, they were also responsible for the implementation of the third part of Fallout, but had to transfer the license rights to Bethesda after their closure by Interplay Entertainment.

This change of responsibilities brought about some radical changes. While the first two Fallout parts still used a 2D engine, an isometric perspective, and turn-based combat, Bethesda Game Studios used an advanced version of their modern Gamebryo engine, either ‘third-person’ or ‘ego’ perspective and an ‘action-heavy’ combat system with tactical elements.

This transformation paid off as Fallout 3 proved to be a great financial success. In the first month after the release alone, more than 610,000 games were sold and the international average score was 91 out of 100 possible points12. Various controversies, for example in Australia, because of the possible use of drugs in the game, or in Japan, because of a mission in which it is possible to detonate a nuclear bomb, could not counteract its continued popularity.

The game itself is located in a post-apocalyptic world in 2277. 200 years after a world war between the USA and China, which culminated in a nuclear war in 2077. The player takes on the role of a “vault” resident. Before the nuclear holocaust, the “vaults”, huge, self-sustaining bunkers, were built all over the United States to protect the country’s elite. But humans also survived the war on the surface and when the father of the player character mysteriously disappears, the player must leave the protective “vault” and follow him into the destroyed remains of Washington D.C. Here he first encounters other survivors who have established settlements and are fighting for their survival. In search of his father, the player must perform various optional and non-optional tasks for the settlers and other groups in order to obtain new clues and information. On his way, other survivors join the player several times for a short time, but the player can never control them himself.

The “karma system” of Fallout 3 is worth mentioning simply because the value of points awarded or deducted here for “good“ and “evil“ actions is explicitly called “karma”. In the game, the “karma system” manifests itself through different solutions to missions, as well as generally “good” actions such as donations and assistance or “bad” actions such as theft and (unprovoked) murder.

The player starts with a fixed number of karma points, which can either be increased or reduced based on his or her own actions. The current value is then used to calculate the karma level, but cannot be viewed directly in the game. The five possible levels are “very evil” (−1000 to −750 karma points), “evil” (−749 to −250 karma points), “neutral” (−249 to +249 karma points), “good” (+250 to +749 karma points), and “very good” (+750 to +1000 karma points). Based on this level and the general level progress, the player then receives a visible title, which is composed as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Karma Titles in Fallout 3.

A differentiation between “very bad” and “bad” and “very good” and “good” does not take place, however.

Besides the title, the player’s karma value also influences dialogues with non-player characters, the availability of special abilities (“perks”) and the outcome of the main plot.

3.4. What Is a Karma System?

The purpose of this section is to formulate a working definition of karma systems and at the same time to preserve the publicly used term “karma system” and its basic meaning derived from the above examples and to distinguish it from other similar game systems. The reason for this is that, there are many games that deal with moral and ethical issues in one way or another, many of which are not associated with “karma” by players and the gaming press.

So what is to be understood here as a “karma system” and what not? To answer this question, one should first start where “karma systems” overlap with other forms of moral decisions in games: The decision between—usually two—moral absolutes.

In the case of a “karma system”, this means that the player is repeatedly confronted with moral questions during the game, which usually offer a relatively clear “good” or “evil” solution, or at least cover two different moral spectra. These questions do not necessarily have to be actual “questions”. They can also be problems that allow different solutions or the player’s actions are constantly monitored during the game and evaluated according to fixed rules (e.g., no civilians may be killed).

Moral decisions can also occur in games that do not use a “karma system”. An example of this would be games such as Bastion by Supergiant Games, in which at the very end of the game the player is prompted to make a single moral decision which decides the fate of the game world. The consequence of the decision is left to the player, as the game immediately ends after the decision. There are no consequences within the game.

In both cases, the decision influences the player’s experience. The difference is that the decisions in the case of “externalized decision systems” like the one in Bastion are both unique and final. Once the player has decided, there are no further repercussions within the game. The player has to make up his or her own mind about the possible consequences—or just ignore them. The moral decisions in “karma systems”, on the other hand, are part of a continuous process of moral development. The player starts in the middle of an alignment or morality chart and the final alignment as well as all consequences take place during the game and can even be undone in some cases. The “karma systems” of Knights of the Old Republic and Fallout 3 are good examples of this.

Another unique selling point of “karma systems” is the evaluation of the player’s decisions by the game or rather the designers of the game. This is usually done using a score scale that shifts depending on the number of “positive” or “negative” points collected, whereby every possible decision that the player can make is bound from the outset to a fixed number of points that can be gained or deducted as a result. This scale is usually directly visible to the player and the player is usually informed immediately of any change in the points account. It is also theoretically possible that the game does not give such clear feedback about the player’s “karma” progress, but it is important that in this case the player’s actions are still ‘recorded’ in the background. It is also important to note that, in the game itself, there is usually no need for a direct ‘witness’—for example in the form of a non-player character (NPC)—so that the player’s actions can be evaluated accordingly.

This aspect distinguishes ‘karma systems’ from ‘consequence systems’ such as CD Projekt Red’s The Witcher. In this system the player is confronted with several—often moral—decisions, which are not evaluated with points, but only decide on the further course of the story at a later point in time. Moreover, these decisions and their consequences are usually directly integrated into the story and can thus be explained in a narrative and conclusive manner.

A final distinguishing feature results directly from the evaluation system mentioned above. A ‘karma system’ is always a closed system in which the moral questions the player is confronted with—whether in the form of dialogues or in the form of direct actions such as theft etc.—are always predefined. If a player carries out an action that is not intended by the designers as part of the ‘karma system’, this action will also not be evaluated by this system, since no corresponding ‘value’ was specified in advance. This can lead to paradoxical situations in which, for example, the player has to kill a larger number of enemies during a mission in order to reach a certain enemy. The game then confronts the player with the decision to spare or kill one enemy. The latter decision is part of the ‘karma system’ and is evaluated accordingly. However, the path to this decision is not part of the ‘karma system’ and thus the killing of the previous opponents is not evaluated by it either.

This closed nature of ‘karma systems’ distinguishes them from games that offer above-average freedom of play and movement. In so-called ‘Open World Games’ like the Gothic series by Piranha Bytes, players are often required to decide for themselves on the moral justifiability of their actions—made possible by the great freedom of play.

On the basis of the observations made here, a first compilation of criteria which constitute a so called ‘karma system’ can be made:

- A ‘karma system’ continuously confronts the player with moral decisions and their consequences.

- These decisions are observed by the game and—visible or invisible to the player—rewarded or punished with points, which are recorded on a scale—also visible or invisible—and influence the further gaming experience.

- The ‘karma system’ is a closed and constructed system. Criteria, rules, and scenarios for the award of points are determined exclusively by the designers of the game.

These criteria should by no means be regarded as conclusive. Still they can provide some insights into the range of possible moral decision making systems present on the current game market. While Point 3 can be seen as the combining factor of all mentioned forms of moral decision making systems, both Point 1 and 2 serve in separating ‘karma systems’ from both ‘externalized’ and ‘consequence’ systems.

In the following chapter, a detailed analysis of the ‘karma system’ of Mass Effect 2 as well as an examination of corresponding processes of reception regarding the concept of karma will be conducted.

4. Mass Effect 2

4.1. Methodology

As proposed in Theorizing Religion in Digital Games (Heidbrink et al. 2014, pp. 16–17), both game-immanent and actor-centered perspectives should be factored in when doing research on the topic of religion and games. The following analysis of the ‘karma system’ of Mass Effect 2 is therefore conducted in three steps which each focus on at least one of these perspectives and build on each other.

The first step is the actual game (system) analysis. The aim is to clarify exactly which game mechanic and rules constitute the ‘karma system’ of Mass Effect 2 and how these are connected with narratives and aesthetics of the game. The result should then be a precise picture of the system with which the players are confronted and which they call the “karma system”.

In the second step, an attempt will be made to discuss the newly drawn image of the ‘karma system’ of Mass Effect 2 from the ‘author’ or game designer’s perspective. This includes a comparison with earlier forms of ‘karma systems’, an examination of the influences of other media such as films or television series, as well as economic considerations. This step is important in that it should prevent a certain degree of ‘overinterpretation’. A separation of the perspectives of designer and player is necessary, since both sides often approach a game and its interpretation with completely different basic requirements.

The third and final step is to focus on the player’s perspective. For the sake of simplicity, representatives of the gaming press will also be included in this category, as they usually take a more player-oriented perspective and are also heavily involved in the coinage and spreading of game related terms. This step is intended to clarify why the ‘karma system’ of Mass Effect 2 is called as such by players in the first place. This means connections with the ideas and interpretations of karma presented in Section 3 of this paper will be drawn and an explanation will be attempted.

4.2. The Game

Mass Effect 2 is a role-playing game developed by Bioware, distributed by Electronic Arts and first released on 26 January 2010. 94 out of 100 possible points for the PC13 and 96 points for the Xbox360 and Playstation 314 were awarded on average.

The game is about Commander Shepard, an officer of the “Alliance”, a coalition of all nations on Earth in 2183, which is in more or less peaceful contact with numerous alien races after the discovery of extraterrestrial technology on Mars in 2148, which makes it possible to travel to distant planets. In the first part of the series, Shepard is named a “Spectre” by the Council of the Citadel, a coalition of space traveling races that have their seat on a massive space station—the Citadel. He is thus granted almost unlimited powers in the pursuit of orders entrusted to him by the Citadel Council. In one of these missions, the pursuit of a renegade Spectre, Shepard encounters evidence of the existence of an ancient race called the “Reapers”, which haunts the universe every few thousand years and wipes out all intelligent life. At the end of the first part, Shepard and the people of the Citadel Council meet a first surprise attack of this threat. Mass Effect 2 takes place two years after this first decisive battle:

Two years after Commander Shepard repelled invading Reapers bent on the destruction of organic life, a mysterious new enemy has emerged. On the fringes of known space, something is silently abducting entire human colonies. Now Shepard must work with Cerberus, a ruthless organization devoted to human survival at any cost, to stop the most terrifying threat mankind has ever faced.To even attempt this perilous mission, Shepard must assemble the galaxy’s most elite team and command the most powerful ship ever built. Even then, they say it would be suicide. Commander Shepard intends to prove them wrong15.

4.3. The Karma System

In the following, the ‘karma system’ is divided into game mechanic, ‘game rules’ and influences on other game elements.

4.3.1. The Game Mechanics

The ‘ergodic element’ of the ‘karma system’ of Mass Effect 2 is achieved primarily by two directly interdependent game mechanic: conducting dialogues and the so-called “interrupts”.

Dialogues play a central role in the Mass Effect series and are used as the main means of continuing the story arc. A so-called “dialogue wheel” is used, in which the player can select the general tendency of the answers to be given—but not their exact wording (see Figure 2).

In some situations, selecting a specific dialog option will result in the credit of either “Paragon” or “Renegade” points. However, the game does not give the player any indication as to whether the current dialogue is such a situation. Also, the game does not directly draw attention to which is the “Paragon” and which is the “Renegade” option. Whether and how many points were credited is only made clear by a message in the game after the selection. The player has no possibility to specifically choose answers based on points given.

The second central game mechanic of the “karma system” is somewhat different: the so-called “interrupts”. These are directly connected to the dialogues and only occur in the course of them. During a dialog, at the bottom of the screen, one or two symbols, each representing a “Paragon” (blue wing) or a “Renegade” (red star) interrupt, appear for a few seconds at certain predefined points (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

“Interrupt” symbols17.

The “interrupt” can then be triggered by pressing the left (Paragon) or right (Renegade) mouse button. Alternatively, the “interrupt” can also be ignored and then has no consequences. When the “interrupt” is triggered, Shepard performs a particularly nefarious or selfless act, depending on the option selected. “Renegade interrupts” usually lead to direct violent—and often spectacularly staged—actions against enemies or threats towards conversation partners and even team mates. “Paragon interrupts”, on the other hand, usually result in the peaceful resolution of conflicts or the protection of the innocent. By triggering “interrupts”, the player is then credited with a relatively high number of “Paragon” or “Renegade” points. Due to clear indication by coloring and symbols, the player knows exactly which decision will bring him which points. This mechanic thus differs from the dialog mechanic. Only the concrete action that Shepard performs after the “interrupt” is hidden from the player in advance.

4.3.2. The Game Rules

The rules of the “karma system” of Mass Effect 2 determine when and how many points are to be credited through dialog options and interrupts, how these are recorded and also what effect these points have.

The concrete situations in which points can be collected were, as already mentioned above, strictly determined by the developers of the game. Outside of these predefined situations it is not possible to change the score of the player. The concrete number of points that can be collected with the respective dialogue options and “interrupts” is also firmly defined and can range from 2 points for a slightly important decision to 45 points for serious decisions throughout the story.

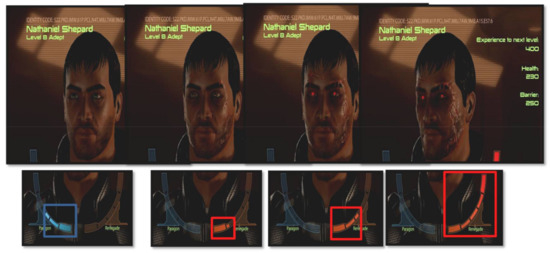

The points are recorded on a two-dimensional scale (see Figure 4). “Paragon” and “Renegade” points are listed separately. No points can be deducted, only new points can be gained, so “making amends” for previous actions is not directly possible; at least not in the same way as in Knights of the Old Republic or Fallout 3.

Figure 4.

Character view with Paragon/Renegade bar.

The respective “Paragon” and “Renegade” values have a number of effects. The consequences for the story and the aesthetics of the game, which will be discussed in more detail in the following sections, include the change in the character’s appearance as well as the general course of action and the course of individual side missions. The latter is made possible by the fact that a certain “Paragon” or “Renegade” score makes additional dialogue options available with which conversation partners can either be persuaded (Paragon) or threatened (Renegade) in order to avoid fights or to achieve discounts with traders.

The rules are based on a fixed point value that must be reached in order to trigger a consequence. Thus the appearance of the character changes only step by step with the achievement of certain “milestones” and also the additional dialogue options can only be activated from a certain, firmly defined point value. The Mass Effect Wiki points out that the availability of dialog options in Mass Effect 2 does not depend on the total number of points currently collected, but rather on a percentage value:

The morality system of Mass Effect 2 works on percentages rather than the total points earned. There is a set number of morality points available in the game. Shepard’s current “effective” morality score at any given point is the number of points earned out of the number of points available from the areas the Commander has explored so far. It is possible to have Shepard’s Paragon/Renegade scale(s) maxed out, but still not have the percentage required for certain dialog options18.

This can also result in a dialog option not being available for the second time when the game is played several times, although it was available with a lower score the first time.

It is also important to note that the moral decisions that the player can make can also have an impact without the respective point value having any influence here. This is especially important at central moments during the main story. For example, the player can decide towards the end of the game, independently of his “Paragon” or “Renegade” value, whether he wants to put the wreck of a technologically very advanced spaceship into the hands of the xenophobic “Cerberus” organization (Renegade) or rather destroy it (Paragon). The player receives points according to his decision. However, the direct effect of his decision (approaching or dissociating himself from “Cerberus”) is not affected by this.

4.3.3. Connections to Other Game Systems

Compared to similar systems, the “karma system” of Mass Effect 2 is distinguished above all by its relatively strong differentiation from other “game systems”. The focus of the decision effects lies in the field of the aesthetics and narratives of the game, which is probably aimed preventing the player from making “moral” decisions for “strategic” decisions in order to get special equipment or abilities instead of actually reflecting on the moral implications of his actions.

Nevertheless, there are some—albeit indirect—effects on other areas of the game. It has already been mentioned that the additional dialog options that are activated with a certain “Paragon” or “Renegade” value can also influence the course of missions and thus the narratives themselves. These dialogue options also offer the possibility to animate traders to discounts on the articles offered by them or to slightly increase financial rewards for completed missions. With the financial means released or gained in this way, the player can theoretically get to better equipment more quickly, which, above all, can reduce the difficulty of the repeated fights in the game.

In this combination of ”karma system” and “battle” and “trading system” it also becomes clear that the game—despite all efforts to avoid this—prefers a way of playing in which the player chooses a single moral orientation. Such a one-sided orientation leads to a faster collection of points, which in turn makes the additional dialog options available more quickly. The concrete advantages of such a playing style are not very serious, however, since the additional financial means hardly matter and the game balance is not noticeably affected. However, depending on the skills and experience of the player, they can still have an influence on his decisions.

The second effect of the “karma system” also falls within the scope of “reduction of the degree of difficulty”. For as already mentioned above, the additional “persuade” and “threaten” options also make it possible to completely avoid battles in certain situations. Here, too, a way of playing is rewarded which focusses on a single moral orientation and thus gets to the corresponding dialogue options more quickly.

4.3.4. Influences on and by the Game Narrative

The most obvious effects of the “karma system” of Mass Effect 2 can be found in the game’s narratives. Indeed, moral dilemmas play a major role in the overall plot of Mass Effect 2. The player has to decide again and again how closely he works together with the mysterious organization “Cerberus”, which Shepard restored after his alleged death through an attack by allies of the “Reapers” at the beginning of the game. “Cerberus” is the only organization in the power network of the Citadel people that takes the threat posed by the Reapers seriously and wants to support Shepard in his fight against them. However, the organization has previously attracted particular attention for its xenophobic attitude towards all races other than humanity and for ethically dubious actions such as scientific experiments on children. Moreover, even during the course of the game, it is never quite clear which agenda the organization itself and its leader, the so-called “Illusive Man”, pursues.

The major plot line of Mass Effect 2, the gathering of a team of specialists to free the human colonists kidnapped by the allies of the “Reapers”, is also all about weighing moral issues; each of the recruited specialists representing a different moral archetype.

This becomes particularly clear in a mission in which the player must recruit one of two possible specialists, each covering opposite moral spectra. Shepard is hired by the Asari people to track down an executor of the law or “Justicar” named Samara and win her over. The “Justicar” of the Asari are notorious for their strict observance and enforcement of a strict moral code of honor. It turns out that Samara is currently looking for Morinth, her own daughter, who, due to a rare genetic effect, is able to increase her own physical and spiritual power by merging her thoughts with those of other intelligent creatures and thus killing them. Morinth has developed into a powerful being, which is at the same time enormously unscrupulous and unpredictable. At the end of the recruitment mission, the player can decide to kill either Samara or Morinth and add the survivor to his team. Samara represents the ideal image of the “Paragon” in this scenario, while Morinth could be described as “Renegade” in its most extreme form.

However, such clear moral extremes are not common in Mass Effect 2 and other companions often turn out to be more complex and their motives usually go beyond pure hunger for power. A good example is Jack, a psychologically gifted young woman whom Shepard has to free from a prison ship and convince to join him. It turns out that Jack was a victim of the above mentioned experiments on children by the “Cerberus” organization and that she is understandably very hostile towards them. But since Shepard is initially still dependent on the support of “Cerberus”, it’s time to find a way to convince Jack to join him anyway, either through clear lies or the honest promise to hold the culprits at Cerberus to account. Such situations then usually lead to the so-called “loyalty missions” in the context of which Shepard must win the final loyalty of his companions by fulfilling a special mission for and with them.

These “loyalty missions” also represent another important point in the effects of the “karma system” of Mass Effect 2, because they usually present the player with particularly difficult moral decisions. However, if loyalty to individual team members is not established by the end of the game—for example, by denying loyalty mission or making moral decisions that the person does not support—then the possibility that this companion will be killed in the final mission of the main action also increases. As a result, this person will no longer appear in Mass Effect 3, the last part of the Mass Effect trilogy. In the most extreme case, even Shepard himself can perish in this mission—of course only after the target has been fulfilled—and can therefore not be taken over into the sequel game (the player then has to create a new “Shepard” for the game). Interestingly, this can happen especially when Shepard follows a consequent “Renegade” course, which also includes lack of personal ties to his teammates. A Shepard with a focus on “Paragon” points and decisions tends to bring more companions and above all himself through the last mission.

What may already become clear here is a slight tendency of the developers to prefer or reward the path of the “Paragon”, at least in the narrative aspects of the game. Although it is also possible to save your team and yourself by focusing on “Renegade” points, it is often necessary to use “Paragon” conversation options to establish the necessary personal ties to the team members. This also illustrates the image that Bioware itself draws of the two ideal types of “Paragon” and “Renegade” and which is summarized as follows in the Mass Effect Wiki:

Paragon points are gained for compassionate and heroic actions. […] Points are often gained when asking about feelings and motivations of characters.[…]Renegade points are gained for apathetic and ruthless actions. […] Many sarcastic and joking remarks are assigned Renegade points19.

The conversation options that lead to better understanding and thus loyalty on the part of the teammates will therefore in most cases be the “Paragon” options.

However, the “karma system” of Mass Effect 2 influences the narrative structures of the game on another level, which is perhaps less obvious. The sheer existence of this system alone often puts action and missions—both main and sub missions—into a framework that leads to decisions between two options from which the player must choose. However, the “karma system” of Mass Effect 2 only knows two values, namely “Paragon” and “Renegade”, which, simply through their presentation in dialogues, the presentation in the character view, as well as through aesthetic aspects, almost impose the image of two moral spectra to be understood as contradictory. Accordingly, each such decision must be assigned a moral value, which contradicts the principle of moral dilemmas actually pursued by the developers.

A good example of how the “karma system” can also superimpose narrative structures and principles is provided by Daniel Floyd, owner of the Youtube Channel Extra Credits20. He refers to a situation in Mass Effect 2 where the player has to decide whether he should wipe out or reprogram a species of artificial intelligences that are hostile to humans and have developed their own consciousness. In the game, the wiping is rewarded with “Renegade” and the reprogramming with “Paragon” points. Floyd comments on this:

This moment in the game really only falls short in one way: Not embedding the question into the game mechanics.As our medium evolves, designers are learning to embed and reference these dilemmas with all the tools that games provide. Mass Effect 2 does a brilliant job of making you live the dilemma of choosing between what may well be genocide and the utter subversion of an entire race’s free will.Unfortunately the designers missed a great opportunity to reinforce this dilemma at its conclusion. If both choices had resulted in renegade points instead of one being labelled the “Renegade” choice, and the other being the good “Paragon” choice, this would have been a fully realized attempt at using the medium of gaming to provide the player with a moment of introspection.Here alone, the designers fell short, looking at the question and the game as separate entities21.

Here the limits of a purely narrative-based game analysis become clear, because before the moral intention of the developers can be examined here, it should be considered that in this case “game system” and narratives were actually treated separately in order to keep the possibility open for the player to finish the game without collecting “Renegade” points.

This view of course opens up new perspectives on the moral intentionality of the developers. However, this should always be taken with caution without appropriately documented statements by the developers themselves.

4.3.5. Influences on the Game Aesthetics

The (visually) most obvious effect of the “karma system” of Mass Effect 2 is in its aesthetics and above all in the aesthetic development of the player character. As already mentioned, Shepard is fatally injured at the beginning of the game by an attack of allies of the “Reapers” and then recovered and restored by “Cerberus”. As a result of this process, slight scars appear on his face after the treatment (see Figure 5). These scars correspond to Shepard’s “Paragon” and “Renegade” value. In the game itself, this is explained in a message that the player receives: “Negative attitudes and aggressive acts create adverse reactions with your cybernetic implants, while peaceful thoughts and compassionate actions promote healing. If you maintain a positive outlook, I believe your facial scarring will heal on its own”.

Figure 5.

Scar development in relation to the “Renegade” value.

If the “Renegade” value is high, the appearance of the player character can change drastically and give Shepard a very gloomy, perhaps even “inhuman” look, with the change taking place gradually and not fluently (see Figure 5).

The “Paragon” value itself does not create any additional change in appearance. A high score in this area only causes Shepard to keep his “normal” face—free of scars; a corresponding visualization of a high “Paragon” value does not exist. At this point there is also the only possibility of making up for “evil” decisions made earlier, because at least the optical effects of the “Renegade” way can be compensated with a sufficient number of “Paragon” points.

Another form of visualization of the “karma system” is found in the coloring of individual game elements; blue stands for the “Paragon” and red for the “Renegade”. This color coding runs through the entire game, such as the respective bars in the character view and the color of the “Renegade Scars” (see Figure 4 and Figure 5) and the respective symbols during the “Interrupts”.

This coding becomes very clear again at the end of Mass Effect 2. During the game, Shepard must keep in touch with the “Illusive Man”, the leader of “Cerberus”. In such moments he is always shown sitting on a chair in front of a red and blue shining sun. Depending on whether the player decides at the end of the game to surrender (Renegade) or destroy (Paragon) the alien ship, the sun is colored either red or blue in the background during the last dialog between Shepard and the “Illusive Man” (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

“Illusive Man”.

Due to the lack of direct comments by developers on the coloring and aesthetic effects of the “Paragon” and “Renegade” values, it makes little sense to attempt to attribute an intention or interpretation to the respective design decisions. However, the influences that may have played a role here will be discussed in more detail in the following sections.

4.3.6. Preliminary Conclusion

In the previous sections, an attempt was made to draw as precise an image as possible of the ‘karma system’ of Mass Effect 2. Among other things, one aspect stands out here above all that runs through the entire system; whether it is the technical implementation of the point system, the concrete design of moral questions or the ‘visualization’ of the system: ‘duality’.

Despite all the efforts of the game developers, it creates the overall impression of a clear juxtaposition of two moral spectra, which are not mutually exclusive from a game rules point of view, but achieve the greatest in-game effect in each extreme. A system of moral grey areas and dilemmas can thus develop into a system of ‘black and white’, of ‘good and evil’. Mind you: ‘can’, but not ‘must’. How the system is ultimately received is always in the player’s view and will therefore also be examined in more detail in the following sections.

But first the view of the game’s developers and designers, Bioware, will be taken to get a better insight into the design process and the influences it is subject to.

4.4. The Game Designer Perspective

It has already been pointed out that attributing certain intentions of game developers when creating a game is an extremely critical process. The main reason for this is that a multitude of factors play a role in the process of game development which are not immediately apparent when looking at the actual game and thus lead to the attribution of meanings which—at least by the developers of the game—were not intended at all.

But how do design decisions come about and what are the factors that can play a role here? Ulf Hagen addressed this question in his article “Where do Game Design Ideas Come From?” He conducted exemplary surveys at four development studios and compiled the “sources of inspiration” in a ranking sorted by importance. First, however, he notes that in most computer games both “new” and “reprocessed” ideas can be found:

My study shows that a game concept generally consists of two parts:

1. The recycled part consists of ideas that has been used before in earlier games, in a movie, a book etc. Usually they can be bundled together under labels—e.g., a genre name (“This is a First Person Shooter game”) or a brand (“This is a new game in the Battlefield series”) or with reference to a film (“The game is based on a film with the same title”).2. The inventive part consists of game ideas that have not been used in the same way in games before. It is hard to make an unambiguous definition of what an inventive idea is, since newness is a relative concept.(Hagen 2009, p. 4)

He then divides the actual design ideas into the following areas:

- The game domain

- (a)

- The game’s (dominant) genre

- (b)

- Another game genre

- (c)

- Another game (or game brand)

- Narratives and visual art

- (a)

- Cinematography and the film domain

- (b)

- Books

- (c)

- Other narratives

- Human activities

- (a)

- Sports

- (b)

- Playful activities

- (c)

- War and warfare

- Human technology and artifactss

- (a)

- Historical or contemporary technology and artifacts

- (b)

- Future technology and artifacts (Hagen 2009, p. 10)

For the context of the study of the ‘karma system’ of Mass Effect 2, above all points 1 and 2—which are to be dealt with under the umbrella term “intertextual and intermedial influences” are of importance, since neither sporting, playful or warlike activities play a direct role here and the recourse to possible future technology can also be neglected.

Another important point that Hagen only touches on briefly is the economic factor (Hagen 2009, p. 3). This includes above all considerations regarding the feasibility and ‘sellability’ of design decisions, because after all, a computer game today is primarily a product that should sell as well as possible.

4.4.1. Intertextual and Intermedial Influences