Validation of the Gratitude/Awe Questionnaire and Its Association with Disposition of Gratefulness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Enrolled Persons

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Gratitude and Awe (GrAw-7)

2.2.2. Dispositional Gratitude (GQ-6)

2.2.3. Life Satisfaction (BMLSS-10)

2.2.4. Wellbeing (WHO-5)

2.2.5. Health Behaviors and Indicators of Spirituality

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants

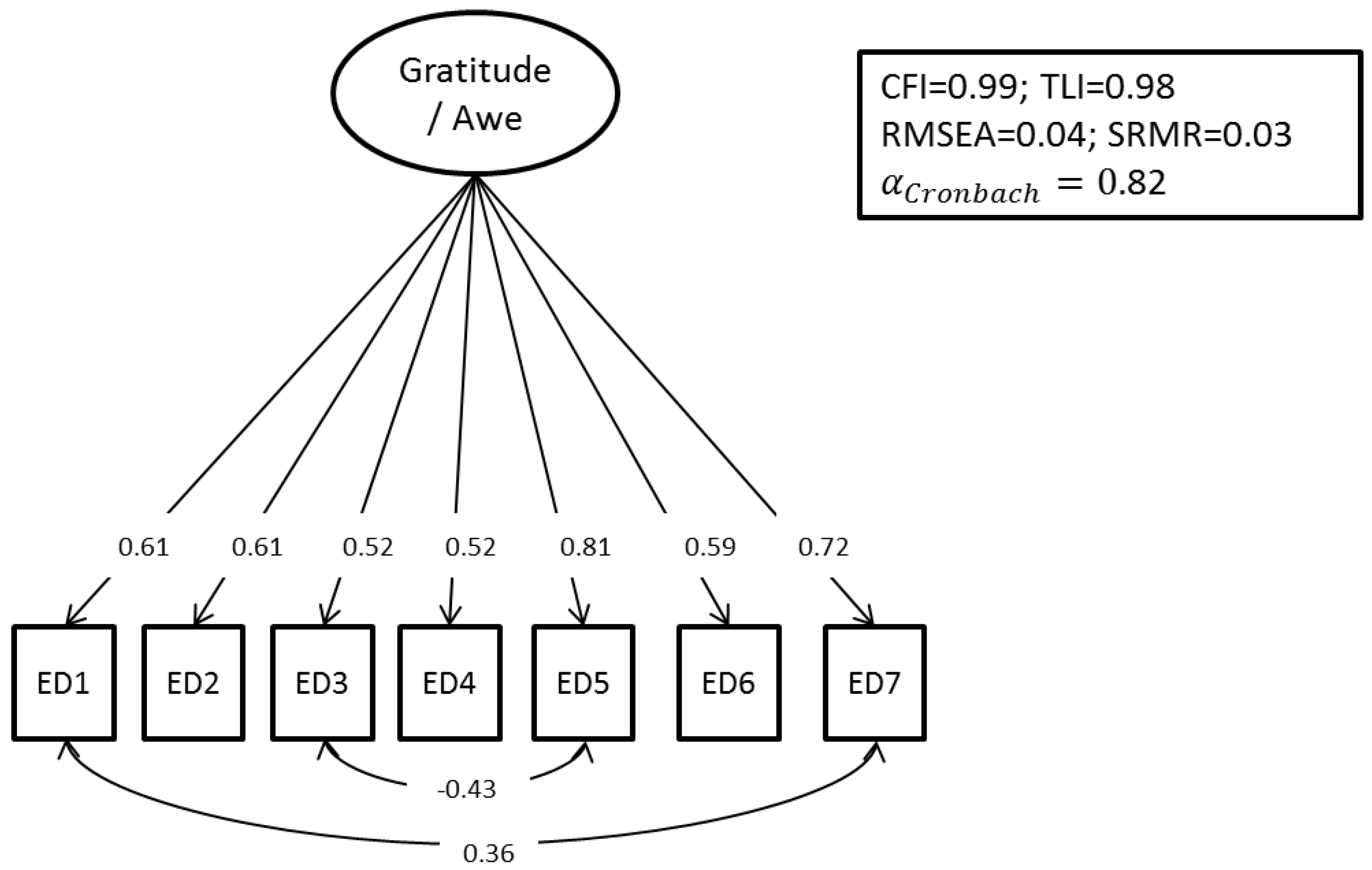

3.2. Reliability and Factor Analysis of the Gratitude/Awe Questionnaire

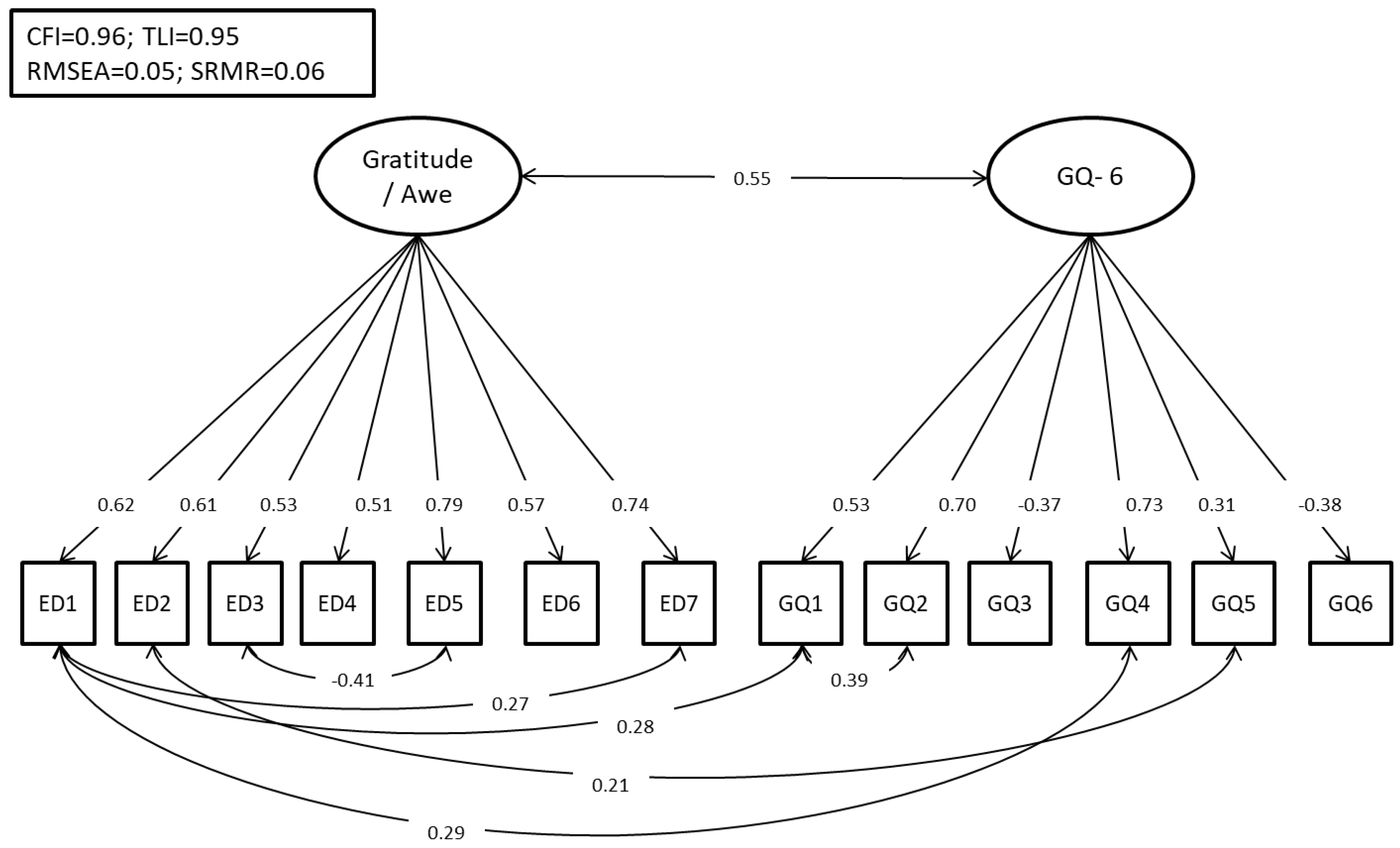

3.3. Structured Equation Model

3.4. Expression of Gratitude/Awe Scores in the Sample

3.5. Correlations between Gratitude/Awe and External Indicators

3.6. Predictors of Gratitude/Awe and Dispositional Gratefulness

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adler, Mitchel G., and Nancy S. Fagley. 2005. Appreciation: Individual Differences in Finding Value and Meaning as a Unique Predictor of Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Personality 73: 79–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algoe, Sara B., and Jonathan Haidt. 2009. Witnessing excellence in action: The “other-praising” emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration. Journal of Positive Psychology 4: 105–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algoe, Sara B., and Annette L. Stanton. 2012. Gratitude When It Is Needed Most: Social Functions of Gratitude in Women with Metastatic Breast Cancer. Emotion 12: 163–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bech, Per, Lis Raabaek Olsen, Mette Kjoller, and Niels Kristian Rasmussen. 2003. Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: A comparison of the SF-36 mental health subscale and the WHO-Five well-being scale. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 12: 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büssing, Arndt, Peter F. Matthiessen, and Thomas Ostermann. 2005. Engagement of patients in religious and spiritual practices: Confirmatory results with the SpREUK-P 1.1 questionnaire as a tool of quality of life research. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 3: 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büssing, Arndt, Julia Fischer, Almut Haller, Thomas Ostermann, and Peter F. Matthiessen. 2009. Validation of the Brief Multidimensional Life Satisfaction Scale in patients with chronic diseases. European Journal of Medical Research 14: 171–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büssing, Arndt, Franz Reiser, Andreas Michalsen, and Klaus Baumann. 2012. Engagement of patients with chronic diseases in spiritual and secular forms of practice: Results with the shortened SpREUK-P SF17 Questionnaire. Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal 11: 28–38. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, Arndt, Ane-Gritli Wirth, Franz Reiser, Anne Zahn, Knut Humbroich, Kathrin Gerbershagen, Sebastian Schimrigk, Michael Haupts, Niels Christian Hvidt, and Klaus Baumann. 2014. Experience of gratitude, awe and beauty in life among patients with multiple sclerosis and psychiatric disorders. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 12: 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büssing, Arndt, Eckhard Frick, Christoph Jacobs, and Klaus Baumann. 2017. Self-Attributed Importance of Spiritual Practices in Catholic Pastoral Workers and their Association with Life Satisfaction. Pastoral Psychology 66: 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, Robert A., and Cheryl A. Crumpler. 2000. Gratitude as a human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 19: 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagley, Nancy S. 2012. Appreciation uniquely predicts life satisfaction above demographics, the Big 5 personality factors, and gratitude. Personality and Individual Differences 53: 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häußling, Angelus. 1988. Dank/Dankbarkeit. In Praktisches Lexikon der Spiritualität. Edited by Christian Schütz. Freiburg: Herder, pp. 205–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Patrick L., and Mathias Allemand. 2011. Gratitude, Forgiveness, and Well-Being in Adulthood: Tests of Moderation and Incremental Prediction. The Journal of Positive Psychology 5: 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, Dacher, and Jonathan Haidt. 2003. Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition and Emotion 17: 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., Robert A. Emmons, and Jo-Ann Tsang. 2002. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82: 112–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, Klaus. 2006. Ehrfurcht. In Handbuch Theologischer Grundbegriffe zum Alten und Neuen Testament. Edited by Angelika Berlejung and Christian Frevel. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, pp. 140–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pearsall, Paul. 2007. Awe: The Delights and Dangers of Our Eleventh Emotion. Deerfield Beach: Health Communications Inc., ISBN 978-0-7573-0585-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pettinelli, Mark. 2014. The Psychology of Emotions, Feelings and Thoughts. OpenStax-CNX Module: m14358. Available online: https://cnx.org/contents/vsCCnNdd@130/The-Psychology-Of-Emotions-Fee (accessed on 20 February 2018).

- Piff, Paul K., Pia Dietze, Matthew Feinberg, Daniel M. Stancato, and Dacher Keltner. 2015. Sublime sociality: How awe promotes prosocial behavior through the small self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 108: 883–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schimanowski, Gottfried, Helmut Schultz, Hans Helmut Eßer, Karl Heinz Bartels, and Jürgen Fangmeier. 1997. Dank/Lob. In Theologisches Begriffslexikon zum Neuen Testament. Edited by Lothar Coenen and Klaus Haacker. Wuppertal: R. Brockhaus Verlag, pp. 239–51. [Google Scholar]

- Shiota, Michelle N., Dacher Keltner, and Oliver P. John. 2006. Positive emotion dispositions differentially associated with Big Five personality and attachment style. Journal of Positive Psychology 1: 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, Michelle N., Dacher Keltner, and Amanda Mossman. 2007. The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cognition and Emotion 21: 944–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellar, Jennifer F., Amie M. Gordon, Paul K. Piff, Daniel Cordaro, Craig L. Anderson, Yang Bai, Laura A. Maruskin, and Dacher Keltner. 2017. Self-Transcendent Emotions and Their Social Functions: Compassion, Gratitude, and Awe Bind Us to Others through Prosociality. Emotion Review 9: 200–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, Demian. 2011. The Feeling Theory of Emotion and the Object-Directed Emotions. European Journal of Philosophy 19: 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisse, Stephan. 1988. Ehrfurcht. In Praktisches Lexikon der Spiritualität. Edited by Christian Schütz. Freiburg: Herder, pp. 267–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Alex M., John Maltby, Neil Stewart, and Stephen Joseph. 2008. Conceptualizing gratitude and appreciation as a unitary personality trait. Personality and Individual Differences 44: 619–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scores | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (Mean ± SD) | 51.8 ± 15.5 |

| Gender (%) | |

| Women | 67.5 |

| Men | 33.0 |

| Educational level (%) | |

| Secondary school (Haupt-/Realschule) | 21.5 |

| High school (Gymnasium) | 77.3 |

| other | 1.1 |

| Religious denomination (%) | |

| Catholic | 39.8 |

| Protestant | 19.3 |

| Other | 16.6 |

| None | 24.3 |

| Items | No Response (n) | Mean | SD | Difficulty Index (2.04/3 = 0.68) | Item to Scale Correlation | Alpha If Item Deleted (alpha = 0.824) | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED7: I stop and then think of so many things for which I am really grateful | 5 | 1.84 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.693 | 0.778 | 0.802 |

| ED5: I pause and stay spellbound at the moment | 3 | 1.73 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.661 | 0.784 | 0.783 |

| ED1 I have a feeling of great gratitude | 0 | 2.17 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.585 | 0.798 | 0.725 |

| ED2: I have a feeling of wondering awe | 2 | 1.85 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.586 | 0.798 | 0.707 |

| ED6: In certain places, I become very quiet and devout | 3 | 2.02 | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.530 | 0.808 | 0.661 |

| ED4: I stop and am captivated by the beauty of nature | 1 | 2.26 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.486 | 0.814 | 0.594 |

| ED3: I have learned to experience and value beauty | 2 | 2.44 | 0.56 | 0.81 | 0.433 | 0.820 | 0.545 |

| Gratitude/Awe (GrAw-7 Sum) | Gratitude (GQ-6 Sum) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gratitude/Awe (GrAw-7) | 1.000 | 0.418 ** |

| Gratitude/Awe (SpREUK-P) | 0.833 ** | 0.478 ** |

| Life satisfaction (BMLSS-10) | 0.148 | 0.332 ** |

| Wellbeing (WHO-5) | 0.293 ** | 0.247 ** |

| Frequency smoking | −0.083 | −0.079 |

| Frequency alcohol consumption | −0.152 | −0.103 |

| Frequency sporting activities | 0.147 | 0.141 |

| Frequency meditation | 0.407 ** | 0.332 ** |

| Frequency praying | 0.341 ** | 0.442 ** |

| Age | 0.205 ** | −0.038 |

| R2 | Beta | T | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: GrAw-7 | 0.26 | |||

| (constant) | 7.237 | <0.0001 | ||

| Life satisfaction (BMLSS-10) | 0.010 | 0.127 | 0.899 | |

| Wellbeing (WHO-5) | 0.174 | 2.206 | 0.029 | |

| Meditation | 0.323 | 4.614 | <0.0001 | |

| Praying | 0.201 | 2.815 | 0.005 | |

| Dependent variable: GQ-6 | 0.29 | |||

| (constant) | 14.619 | <0.0001 | ||

| Life satisfaction (BMLSS-10) | 0.278 | 3.724 | <0.0001 | |

| Wellbeing (WHO-5) | −0.032 | −0.417 | 0.678 | |

| Meditation | 0.184 | 2.688 | 0.008 | |

| Praying | 0.345 | 4.923 | <0.0001 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Büssing, A.; Recchia, D.R.; Baumann, K. Validation of the Gratitude/Awe Questionnaire and Its Association with Disposition of Gratefulness. Religions 2018, 9, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9040117

Büssing A, Recchia DR, Baumann K. Validation of the Gratitude/Awe Questionnaire and Its Association with Disposition of Gratefulness. Religions. 2018; 9(4):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9040117

Chicago/Turabian StyleBüssing, Arndt, Daniela R. Recchia, and Klaus Baumann. 2018. "Validation of the Gratitude/Awe Questionnaire and Its Association with Disposition of Gratefulness" Religions 9, no. 4: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9040117

APA StyleBüssing, A., Recchia, D. R., & Baumann, K. (2018). Validation of the Gratitude/Awe Questionnaire and Its Association with Disposition of Gratefulness. Religions, 9(4), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9040117