4.1. Survey Results

Table 1 summarizes the primary results from the national study. Overall, we found support for the existence of ten cultural package subcategories. There was also evidence of overlap among some of the categories. In particular, Ethical Morality was a crosscutting category that was not a fourth cultural package and rather a more behavior-oriented set of themes than the belief-oriented set of themes described in the three cultural packages. We thus group these below into a section of results on belief-based cultural packages and a second section of results on ethical morality.

4.1.1. Theistic Cultural Packages

Doctrine-Theistic. Many emerging adults described their religious beliefs in ways that were doctrinally specific and theistic. For example, when asked “What would it take for you to stop believing, if anything?” one emerging adult said, “This answer won’t make sense, but it’d take Jesus to come and tell me that the Bible is wrong.” Another described reading the Bible and said he did this because, “the Lord wants to be in a relationship with us, and my being in a relationship with God is the way that I talk to Him through prayer, but the way I hear from him, most times, is through his word, I think.” He goes on to say: “So, I read it to be in a relationship with Him; I read it to hear from Him; I read it to be comforted; I read it to know what’s right.”

While these two examples came from Christian emerging adults, there are also many emerging adults who are not Christian in the Doctrine-Theistic group. For example, a Hindu emerging adult stated, “We’re Hindus. Spiritually there’s an organization called Swadhayaya, which means self-study. So, spiritually we follow that.” She continues by describing her faith’s tenets in this way: “We really just focus on ourselves, and the scripture that we focus on is the Gita, which all Hindus know about.” Likewise, a Jewish emerging adult stated: “The Torah is the foundation of Jewish belief, and we believe that God gave it to Moses at Mount Sanai and that it came right from him or the being, general neutral being.” He continues by stating, “That’s kind of a foundation and then [there is] the Talmud which is tens of thousands of laws.” Describing himself as a reformed Jew, he explains: “Reformed Jews aren’t really [supposed to] have a lot of Talmudic influence in their life, but I think that came from God too. So while I’m not as studied in it, I do believe in it and its importance.” Of the 300 interviews in the sample, 69 of them were emerging adults we categorized to be Doctrine-Theistic.

Hybrid-Theistic. Also under the broader Theistic cultural package was a subgroup of “tinkerers,” who combine doctrine from different faith traditions. For example, when asked what she believed, one emerging adult said, “Like, the deities and, like, the Hinduism and Buddhism and things like that, and I kinda just, like, pick and choose, like, what I like out of everything, so.” She described where these combined beliefs came from by saying, “Just learning about a lot of the beliefs that people in yoga tend to have.” Another emerging adult asked to describe his religion said, “Islam and Hinduism, I think.” The interviewer asked, “Both of those?” To which he replied, “Yes, the combining of the two.” A third emerging adult summed this category well when she stated, “Maybe I’m like omni-religious.” While we found evidence for the existence of this category, there were only three emerging adults who expressed their religious beliefs in a way that could be described as Hybrid-Theistic and without overlapping into another category.

Therapeutic-Theistic. Another large group comprised of individuals who employed religion for its emotional and spiritual benefits, but differed from the Doctrine-Theistic group due to their lack of emphasis on established doctrine, traditions and involvement. Many of the emerging adults in this group were secure in their beliefs, but not necessarily concerned about making religion a core aspect of their identity with one participant identifying that she only prays as a “last resort kind of thing.” One interviewee described his relationship with God as “a distant friend I guess. Someone I look up to and know is around, um, but don’t always feel accountable to.” Especially common in this group was a reliance on God for support during troubling times with one young woman, who described herself as a “pretty bad Catholic,” saying that she uses religion primarily as a means to “cope with certain things in my own head, and that’s what gets me through.” Akin to

Smith and Denton (

2005), we view this group as a Therapeutic-Theistic package that has religiosity in its belief contents but which is not based on any particular religious doctrines. Overall, 53 of the 300 emerging adults were categorized into this group.

Heritage-Theistic Package. This final group is comprised of respondents who identified as religious, but who actively exhibit little religious practices or beliefs. This group primarily consists of people who were born and raised within their faith tradition, such as one participant stating that she was a Christian because that was “how I grew up, so that’s what I believe.” However, a disconnect between belief and practice exists within this group. When one emerging adult was asked what his religious affiliation was, he responded with a noncommittal reference to his upbringing: “like growing up had a strong Catholic um, Christian tradition.” He identified that he was religiously inactive, but said that Christianity was still “part of my heritage.”

Many aspects of religion are still salient with emerging adults in this group, but without any description of religious content as presently meaningful to them, other than through a heritage connection with family and traditions. For example, one interviewee explained that on Christmas “we have presents and stuff. We don’t go to church or nothin’ though.” Many Jewish emerging adults, describing themselves as culturally Jewish, occupied this group. One Jewish man stated both that he observed “like the blood heritage of the Jews,” but also said: “I’m not religious at all.” The themes of family ties and intergenerational commitment permeated this group. Of the 300 interviews, 63 were identified as Heritage-Theistic.

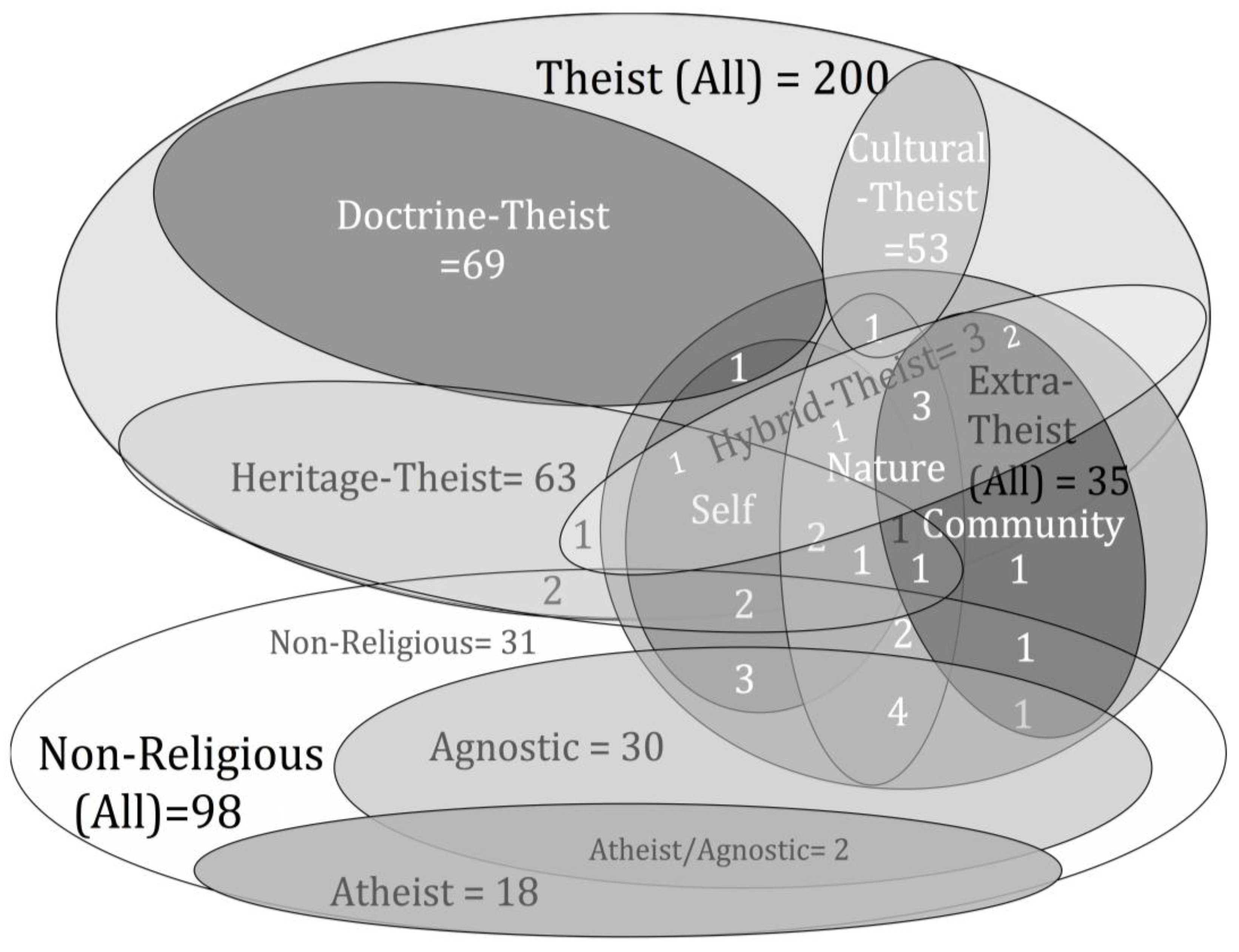

Combined, a total of 188 of the 300 interviewees were categorized in the Theistic cultural package. In addition, another 12 interviewees expressed some aspects of Theism but also described the contents of one of the other cultural packages. Of these partial-theistic interviewees, one was part-doctrinal, five part-hybrid, one part-cultural, and five part-heritage. If counted within the Theistic Package, this equates to two-thirds of these emerging adults.

4.1.2. Extra-Theistic Cultural Packages

Self-Extra-Theistic. Among emerging adults who emphasized spirituality, some emerging adults experienced religion and spirituality as being rooted, in part, by inward reflection and self-actualization. For example, A Buddhist emerging adult expressed the belief that each person has the opportunity to achieve “Buddha nature or their highest potential.” She elaborated further by stating that she believes that all religions are rooted in the same core belief: “that each one of us has this higher potential, and we try to bring that out.” Furthermore, another interviewee conveyed that he believed that “some people’s personalities are just too, too big to just cease being,” though he added: “I don’t know what that means though.” Common themes in this group consist of schools of thought outside of Western Religion, like Buddhism, and meditation and mindfulness, some of which overlapped with Doctrine-Theistic and Heritage-Theistic packages. Similar to Nature-Extra-Theistic, we did not classify any interviewee solely as Self-Extra-Theistic, rather 11 were partially in this group.

Community-Extra-Theistic. Other emerging adults experienced religion through their social relationships with other people. One young man expressed his belief that “God is within, God is among us” and that spirituality is represented by “extending our love through our experience.” Auras and spiritual, energy connections between individuals are another common theme in this group. One interviewee described her energy as being like a “bubble” that has the ability to affect other people, and inversely other people’s energy can affect her back. She described: “I’m sitting here, and my body doesn’t really end here.” Similarly, another emerging adult emphasized the uniqueness of each individual’s energy stating that: “when you add one person to a group of like five people, that one person is gonna change the dynamic of the whole group and that’s because of the energy they bring in.” Overall emerging adults in this group described feeling a spiritual, but yet almost tangible link between themselves and others. This link affected the way they organized their spirituality. In terms of how many interviewees were in this category, it shared a commonality with the other Extra-Theistic packages in having more overlap than non-overlap, with nine emerging adults partially expressing Community-Extra-Theism. Unlike the other extra-theistic cultural packages, there was one individual who we exclusively categorized as Community-Extra-Theistic. Together, there was only one emerging adult who was solely Extra-Theistic, though there were an additional 34 interviewees who expressed one of the three types of extra-theism partially, in combination with the Theistic or the Non-Religious packages.

Nature-Extra-Theistic. Connectedness to nature was frequently referenced among emerging adults who emphasized spirituality. One Christian emerging adult described God as being a part of everything by saying: “I feel like God is in you, and God is in me. I feel like God is in the air. God is in the electricity.” In other interviews, Nature-Extra-Theism was used to join science and religion together. One participant described spirituality as “kind of like um, in physics you have entropy. And so that’s just like the natural degradation of everything around you. And so for me, my spirituality, it helps me to fight against that entropy basically.” In addition, emerging adults in this category saw religion and spirituality reflected in, as one emerging adult put it, “both the beauty and power, as well as the sorrow and irrationality of nature.” While no participant was categorized as exclusively Nature-Extra-Theistic, 14 emerging adults were partially Nature-Extra-Theistic, while also expressing content that overlapped another of the cultural packages.

4.1.3. Non-Religious Cultural Packages

Non-Religious. In contrast to the two prior groups, some emerging adults explicitly described themselves as being without a religious affiliation of any kind. These Non-Religious emerging adults can be further separated into three groups. Some of the Non-Religious emerging adults constructed their identity in a more passive way. One interviewee stated “I definitely don’t acknowledge myself [as] bein’ religious.” However, he continues by describing that his religious values were so ingrained into him that “I can’t shake them.” Contrary to Heritage-Theistic individuals, many of these emerging adults de-emphasized religion or spirituality and did not have a strong identification with the religion of their heritage. For example, one young woman said, “I wish I went to church more, but more because I kinda miss that community of church.” She then said: “other than that I’m not a spiritual person; I’m not a religious person.” Conversely, other Non-Religious emerging adults constructed their identity in a more active and reactionary manner. These individuals expressly rejected the labels of Agnostic and Atheist, and created their own labels for themselves. One emerging adult recognized the importance that religion played in many people’s lives. However, he viewed religion “as judgmental and not open to change or any kind of sort of personal thought process.” He said he considered religion to be “just one of those things that I find it’s not for me.” Another individual who identified himself as Non-Religious said, “I would say that I believe in a higher being, like God, but I think that that is a really broad and big concept.” Furthermore, he rejected other theistic or nontheistic labels due to his belief that religion is “a personal experience; it’s a personal idea.” In this way, he shared some overlap with the Self-Extra-Theistic package. Overall, we categorized 31 of these emerging adults as Non-Religious, with an additional six who we categorized as partially Non-Religious.

Non-Religious-Agonistic. In addition, other emerging adults more explicitly identified as agnostic or were characterized by their not knowing the truth of any religion. As one emerging adult explained, “people think that an agnostic is someone who just sits on the fence and doesn’t care either way.” However, he stated that he does care and identified as “an agnostic theist,” which he described as someone who states: “that you don’t know.” He further added: “everybody’s agnostic. They just don’t want to admit it.” Other young people express agnosticism as a way to rectify science and religion together. These emerging adults believe there is no way to scientifically identify whether God is real. However, as one emerging adult describes: “If God is omnipotent, then why couldn’t have God created photosynthesis? Why couldn’t he have God created evolution?” Thus, some in this category are partially Theistic in their cultural package, but with the distinct difference that they explicitly state not knowing if they believe theistically. Another common theme in this category was references to events in religious upbringings that pushed youth away from theistic beliefs. For example, one young woman expressed the discomfort she felt when her youth pastor told her “God punished [R&B singer] Aaliyah, and that’s why she died.” She expressed: “with me religion kinda comes with judgment,” and she attributes that experience as having prevented her from being fully Theistic. In total, there were 30 emerging adults in this study who we identified as being Non-Religious Agonistic. In addition, agnostic emerging adults were the most likely to also express Extra-Theistic beliefs, with another ten of our interviewees expressing partially agnosticism in overlap with another cultural package.

Non-Religious-Atheist. The last of the belief-based groups is characterized by a firmer rejection of religion, theism, and spirituality of any kind. In describing their rejection of religious and spiritual beliefs, some of these emerging adults explained that they had logically reasoned themselves out of believing. For example, some attributed the problem of evil for their atheism. One interviewee explained: “If the world were all sunshine and roses, I might be more inclined to believe that there was somebody pulling the strings … but I can’t believe that there’s someone pulling the strings making genocide.” Another emerging adult expressed: “I still get told I’m going to hell, and so that has always made me, it led me to research other religions.” Other young people identified with atheism simply as a reflexive rejection of theism. One young man explained, “I think I probably would consider myself to be atheist, but my atheism is not a central part of anything.” Another young woman described that, “The only time I labeled myself like that [as an atheist] was when I was in the military, and that’s simply because you had to.” Only 18 of the 300 emerging adults in this sample were solely categorized as atheist, with an additional three partial atheists.

Combined, 79 of these emerging adults were solely Non-Religious, with an additional 19 who were partially Non-Religious. This equates to nearly one-third of the interviewees, for the second largest cultural package grouping, smaller than Theistic but larger than Extra-Theistic. Thus, one of the most evident findings of these results is confirmation of the initial overlap in categories identified by

Ammerman (

2013), with even further overlap found among a larger and national sample of emerging adults.

Figure 1 visually represents these overlaps and shows that emerging adult religiosity and spirituality combine into non-binary categories.

4.1.4. Ethical Morality

The second set of results describes our qualitative analyses of the morality questions.

Ammerman (

2013) describes ethical spirituality as a “common denominator,” since the one thing all forms of religiosity and spirituality agree upon is “living a virtuous life” (p. 272). As with the belief-based cultural packages, we were curious about the source of ethical spirituality and viewed it as possibly cross-cutting the above sets of belief-based cultural packages. In investigating the source of ethicality, we find that responses grouped into two subcategories: Tacit-Morality and Cognitive-Morality. These descriptions refer to the extent to which interviewees described having conscious access to reasons for ethical decision-making or not.

Tacit Ethical Morality. When we asked emerging adults about their morality, and how they make decisions about right and wrong, many told us, “a gut feeling.” For example, one emerging adult said, “your gut. I mean if you feel it’s wrong, then it’s probably wrong.” Another said, “I know. It’s just a, I don’t know, a gut feeling, you know what’s right and what’s wrong.” This interviewee went on to say: “I guess the hard part is deciding what to do about it, how to act on it, but um I don’t really have, I never find myself thinking too hard about what’s right and what’s wrong.” Many of these responses were not described as having a religious basis, totaling to 117 interviewees. An additional 98 of these responses came from emerging adults who described their gut feeling as stemming from religious beliefs. Similar to the first grouping, these emerging adults described morality as clear, straightforward, and relatively easy to apply to the right and wrong decision to make. Unlike the previous group, they described the reason for this being that morality was ingrained in them from their religious upbringing. For example, one interviewee said, “It’s a lot a part of like who I am and like, and what I’ve learned from like church and the Bible and from God.” She continues by saying she does not typically have to give it much thought because, “It usually is evident just because of who I am.” Another emerging adult describes their tacit sense of morality by saying, “It would have to do with my religious background, [how] I was brought up. And then once again the values and the morals that were, that I was taught.” As one emerging adult aptly described a tacit morality by saying, “I just kind of know.” But in the same sentence, this interviewee also listed the sources for this morality as: “the Bible, my mom.” When asked whether it was easy or hard to know what was right or wrong in a situation, another emerging adult said, “[I] think it’s usually pretty clear. I mean, there’re occasionally tough situations. And life’s full of surprises. But I think most of the time, the answer’s pretty straightforward.” Yet another said, “scripture is very clear,” and another said they implicitly know because, “it’s just already inside of me from studying the Bible and being so involved in the Christian lifestyle.” Combined, these 98 religiously infused tacit morality add to the 117 not specifically religious tacit morality interviewees to a tally of 215 of 300 emerging adults, more than two-thirds of the sample.

Cognitive Ethical Morality. In contradistinction to the emerging adults who described their sense of morality as tacit, ingrained, easy, and straightforward, another group talked instead about engaging in active cognitive effort to decide their sense of right and wrong. We call this cognitive morality, and view it as evidenced by statements such as: “I think it’s much more important to be critically, to critically think about your own life and your own decisions.” This emerging adult called it “dangerous” to “blindly accept” morality as prescribed by any social institution and instead thought morality deserved conscious attention. Another emerging adult described, “If something affects me, emotionally, immediately, I try to fall back, take a step back from the situation, and think about it. ‘Cuz, you know, we [are] all human, we [are] emotional creatures. And sometimes we do irrational things because of our emotions.” As opposed to the group who said morality was implicit and easy, another emerging adult in this group said the process of deciding right and wrong in this way: “I weigh out how it affects others, how it affects me, and then kinda go from there.” Similarly, another said, “I try to think about how it’s going to affect anyone who’s involved, and if nobody’s negatively affected then it’s probably not bad.” Yet another said, “It’s tough, because everything’s a grey … It’s very hard.” The emerging adults in this cognitive morality group who did not explicitly mention engaging religious or spiritual content in their moral decision-making tallied to 66 interviewees. As with tacit morality, this cognitive morality group also had a second subcategory that described a similar process but also described religious or spiritual content. This was the smallest grouping of the ethical morality coding, with only seven interviewees explicitly in the religiously infused cognitive morality category. These emerging adults were typified by statements such as, “In Judaism there’s more of a religion of laws than people realize…It’s not about what you feel; it’s about what you do. Which I know is more of a lawyer way to look at the world, but that’s why there are so many Jewish lawyers I think (laughs).” While this cognitive morality emerging adult describes thinking through right and wrong based on scriptures, another discusses relying upon praying and asking others: “Usually I would, like, pray about it … I will ask someone’s opinion. The people’s opinion, who I think are more experienced in life than me.” Another emerging adult in this category describes wrestling with personal desires versus religious teachings: “A lot of it comes down between personal feelings and religion. So, later on like, if I’m not in tune with my religious or spiritual self and I’ll do it [make a wrong decision], and I don’t help them [a person in need], and I get home and I feel bad, [then I know] that was the wrong choice. I shoulda done it.” Another interviewee summarizes this group by saying their thought process is to ask: “What would be the moral high ground to take in a situation like this?” Then says, “and that’s usually what I do.” There were only seven in this religiously infused cognitive morality group; the other 66 cognitive morality emerging adults did not mention religion. Combined, these tally to 73 interviewees, less than one-quarter of the sample.

In addition, there were many interviewees that we categorized as a mixture of these tacit morality and cognitive morality categories. One interviewee at times described a non-religious tacit sense of morality, while at others drew upon a religious tacit sense. Another at times sounded similar to the non-religious tacit morality group, while at other times in the interview sounding the same as a religiously infused cognitive morality interviewee. An additional three expressed a combination of non-religious tacit and religious tacit, and eight interviewees described their morality in ways that combined non-religious tacit with non-religious cognitive morality. In summary, emerging adults described their ethical morality in ways that we categorized into two broad categories: implicit and cognitive. Each of these had subcategories of religious and non-religious, and there was a small group of emerging adults who evidenced hybridization across all four of these categories. Ethical morality codes were crosscutting with the three belief-based cultural packages, as the content of the religious or non-religious beliefs described was consistent with the theistic, extra, and non-religious categories.

Thus, we find that more than two-thirds of these emerging adults expressed a tacit ethical decision-making process, with their sense of morality internalized beyond cognitive access and without need of conscious attention. Slightly more than half of these described the source of their sense of morality in non-religious terms, while nearly a half described a religious source.

4.2. Experimental Results

In response to this national-level finding on the general dearth of reflexivity regarding the moral basis for ethical decision-making, we conducted a second study that investigates changes over time in response to an experimental intervention designed to increase moral awareness.

4.2.1. Clarifying Moral Values

At Time 1 of the experimental study, two-thirds (75 percent) of the emerging adults in both the primary and control groups said they had positive feelings toward and understood their faith, and nearly three-quarters (71 percent) reported that they clearly understood their moral values. However, less than one-tenth (7 percent) said they could easily identify their moral values. At Time 1, 70 percent of the participants said that when faced when difficult life decisions they would decide what to do based on their framework of beliefs and values (as compared to the other response options of what feels right at the time, views of friends, views of parents, and what is most beneficial in the short to medium term). In measuring changes over time, the rate declined by four percent at Time 2 for the comparison groups of similar emerging adults receiving the ethics-only content. In comparison, the rate for emerging adults in the treatment group increased by five percent at Time 2.

Moreover, at Time 2 all the emerging adults in the treatment group reported clearly understanding their beliefs and values. This reflected an increase in agreement with this statement by one-quarter of the group, as compared to no statistically significant change in agreement among control groups. Lastly, net of Time 1 responses, and in comparison to control groups, the treatment group participants had a statistically significant Time 2 decrease in their agreement with personal gain weighing more heavily than principles in their decision-making. This provides some initial evidence that the experimental intervention aids some in making ethical decisions that are based on a clearer sense of values and not solely on personal gain.

4.2.2. Articulated Value Statements

In analyzing the personal mission statements with the cultural package framework described in the first study, half of participants in the experimental intervention explicitly referenced having a Doctrine-Theistic belief system in their value statement. Examples of these values statements are one female emerging adult stating: “My most important value is my faith. It is my way of life and the most critical thing that influences my decisions. My faith in God keeps me centered, calm, and focused. It helps give my life meaning and a distinct purpose. I know God will always be by my side and help me along my journey.” A male emerging adult described, “My mission is to be a man who has an open home and to have an open heart that any who would desire to seek refuge in either would be able to do so readily for the mission that is missions for the Gospel of Christ.”

Another emerging adult described how she saw her moral values impacting her life pursuits by saying, “In this life I want to accomplish great things—at work, school and even in my personal life. Whatever I work at and accomplish I want to point everything back to Jesus because through him I am able to do all things.” In reflecting on future workplace goals, another emerging adult described his values in this way: “My life mission is to be a Christian man in the business world, showing that I am dedicated to my job, my faith and my family … I plan to have my faith in God be the center of my life and be the motivation for all that I do.” In succinctly summarizing how participants with a Doctrine-Theistic belief system articulated the connection to their ethical decision-making, this emerging adult explained her values by saying, “Integrity, to me, means letting my Christian morals guide me in all aspects of life.” One emerging adult articulated an Extra-Theistic belief system that viewed himself as a vehicle for transcendence by saying, “My enthusiasm will light a fire under people to accomplish their own goals as it transfers through my attitude, facial expressions and tone of voice.” He continued: I will show people that by creating their own reality they can innovate in every part of their lives and be more in control of their outcomes than they once were before.”

The remaining nearly one-half of participants did not explicate any religious belief system in their value statement. Examples of value statements from these participants are this from a male emerging adult: “My mission is to always live life to the fullest, bring honor to my family, and continue to defy the odds.” A female emerging adult stated, “I will do this by not blaming my unhappiness on others, pushing my self to strive for new challenges and be honest about my mistakes.” Another female emerging adult said, “I will always stay true to myself and my values, I will continue to learn every day, and I will focus my energy on helping others and maintaining lifelong relationships.” The lack of explication of a belief system did not allow for a more thorough parsing as to whether these participants are Non-Religious in their beliefs, or could have been coded as Heritage-Theistic or Extra-Theistic with access to further information. Nonetheless, it was evident that they did not articulate Doctrine-Theistic beliefs in their value statements, meaning about one-third of the participants who reported clear understandings of their faith and moral values at the beginning of the semester did not by the end of the treatment cognitively link their values to their religious beliefs, while the other two-thirds connected these.

4.2.3. Impact of Value Reflections

In participant essays, emerging adults articulated a number of change mechanisms from the intervention approaches. We coded these into one of five inductively developed themes, listed in order of their prevalence: gaining greater reflexivity, heightened cultural awareness, becoming more concerned about the welfare of others, developing a greater sense of purpose in life, and learning skills to relax and de-stress, the latter of which were primarily gained through meditation techniques taught during the intervention. For this paper, we report the most prevalent results: gaining greater reflexivity. Participant essays in this category made statements such as, “Through this class, my values have been solidified … [This class] is an opportunity to look into yourself and find that what you believe in and what you value, the basis of who you are.” Another emerging adult expressed, “My understanding of my goals, values and mission has undergone a dramatic facelift this semester.” A third said, “[This class] has helped me articulate my values and beliefs while helping me define them when they were unclear.” A fourth emerging adult stated: “I do feel more like I’ve organized my beliefs into a coherent thing instead of the mildly blurry romantic mess they were before.” Thus, it appears from these reports that the intervention was helpful in facilitating participants in gaining greater clarity of their moral values through a process of reflexivity.

In discussing what if any impact this would have on everyday life, one emerging adult said, “I knew some of my goals and values, but I hadn’t really thought much about how I would actually reach it … After having gone through these exercises, I firmly believe I can not only state my goals that I have had but how I will go through my daily life to attain them.” Another said, “This class has given me a new perspective and meaning to my life … By narrowing down my core values to my top five, I am now able to use them daily to make decisions.” Yet another described learning over the semester: “The first draft of my personal mission statement was more focused on what I wanted to feel than what I intended to do, and was very vague and ‘fluffy.’ As I progressed in the course, I began to look further inward and reframe what l wanted into what I could do in order to improve my life.” Thus, it appears from these descriptions that this intervention aided participants in making their moral values more explicit by engaging in a cognitive process of reflexivity. While many of the participants were Doctrine-Theistic, they still had at the outset of the intervention the same general pattern found in the national study of mostly relying upon a tacit sense of their moral values. However, it appears this intervention aided participants in gaining greater access to the taken-for-granted beliefs embedded in their ethical decision-making and a sense of how to clearly articulate this to others. Participant descriptions indicate this change will continue to impact their ethical decision-making.