Towards National Consensus: Spiritual Care in the Australian Healthcare Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- A nationally consistent governance framework to ensure quality and safety in spiritual care services;

- Viable and sustainable spiritual care models; and

- Quality education and training.

2. The National Consensus Conference

2.1. Sequence of Events

2.2. Participants

2.3. Conference Proceedings

- Governance

- Education/Training

- Credentialling

- Accreditation

- National advocacy/communication strategy

- The Uniqueness Principle (what is unique, distinctive about spiritual care?)

3. Results

4. Discussion

- How will we demonstrate the contribution spiritual care makes to quality of care?

- How can we co-design models for spiritual care to ensure spiritual care is provided in response to people’s identified needs?

- What is the role of the faith communities as partners in the provision of spiritual care?

- What is the pathway for formation of a competent spiritual care practitioner?

- How will we ensure a credentialled and accountable workforce?

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016. Census Data—Religion. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/mediareleasesbyReleaseDate/7E65A144540551D7CA258148000E2B85?OpenDocument (accessed on 28 September 2018).

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2011. Patient-Centred Care: Improving Quality and Safety through Partnerships with Patients and Consumers; Sydney: ACSQHC.

- Best, Megan, Phyllis Butrow, and Ian Olver. 2014. Spiritual support of cancer patients and the role of the doctor. Supportive Care in Cancer 22: 1333–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckett, Stephen. 2016. Targeting Zero: Supporting the Victorian Hospital System to Eliminate Avoidable Harm and Strengthen Quality of Care; Report of the Review of Hospital Safety and Quality Assurance in Victoria. Edited by Department of Health and Human Services. Victoria: Victorian Government.

- Fitch, Margaret I. Supportive care for cancer patients. Hospital Quarterly 3: 39–46. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, John. 2000. The quality of Australian health care study: Implications for education of failure in quality and safety of health care. Education for Health 13: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, John D., Robert W. Gibberd, and Bernadette T. Harrison. 2014. After the Quality in Australian Health Care Study, what happened? The Medical Journal of Australia 201: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healthcare Chaplaincy Network. 2015. What Is Quality Spiritual Care in Health Care and How Do You Measure It? New York: Healthcare Chaplaincy Network. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Cheryl. 2017. National Consensus Conference Report Enhancing Quality & Safety: Spiritual Care in Health. Melbourne: Spiritual Health Victoria. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Cheryl. 2018. Stakeholder views on the role of spiritual care in Australian hospitals: An exploratory study. Health Policy 122: 389–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, R. Adam. 2013. The Policy Delphi: A Method for Identifying Intended and Unintended Consequences of Educational Policy. Policy Futures in Education 11: 755–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaningful Ageing Australia. 2016. National Guidelines for Spiritual Care in Aged Care. Parkville: Meaningful Ageing Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Puchalski, Christina. M., Robert Vitillo, Sharon Hull, and Nancy Reller. 2014. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine 17: 642–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumbold, Bruce. 2012. Models of Spiritual Care. In Textbook of Spirituality in Healthcare. Edited by Mark Cobb, Christina Puchalski and Bruce Rumbold. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 177–84. [Google Scholar]

- Spiritual Care Australia. 2013. National Standards of Practice. Melbourne: Spiritual Care Australia. [Google Scholar]

- The Independent Hospital Pricing Authority. 2017. Reference to Changes for ICD-10AM/ACHI/ACS Tenth Edition 2017; Darlinghurs: The Independent Hospital Pricing Authority.

- Wilson, Ross. 2005. The safety of Australian healthcare: 10 years after QAHCS. Medical Journal of Australia 182: 260–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| 1 | Spiritual Care Australia is the national professional association for organisations and individual practitioners in spiritual care services. The association seeks to unify, consolidate, support, promote & encourage the development of spiritual care within contemporary multi-faith, multi-cultural Australia. |

| 2 | Spiritual Health Victoria is the peak body enabling the provision of quality spiritual care as an integral part of all health services in Victoria (Australia). |

| 3 | The Community of Practice (Health) is made up of representatives of state based organisations for spiritual care auspiced by Spiritual Care Australia. |

| 4 | Dr Norman Swan is a multi-award-winning producer and broadcaster. He was one of the first medically qualified journalists in Australia. |

| 5 | Dr Stephen Duckett is an economist and health services manager who has occupied leadership roles in health services in both Australia and Canada. He is currently program director of Health at the Grattan Institute (an Australian public policy think tank). |

| Principles for Design and Delivery of Spiritual Care Services | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Spiritual care is integrated and coordinated across all levels of the health system in Australia. |

| 2. | Spiritual care is available for all people. |

| 3. | Spiritual care is provided by a credentialled and accountable workforce. |

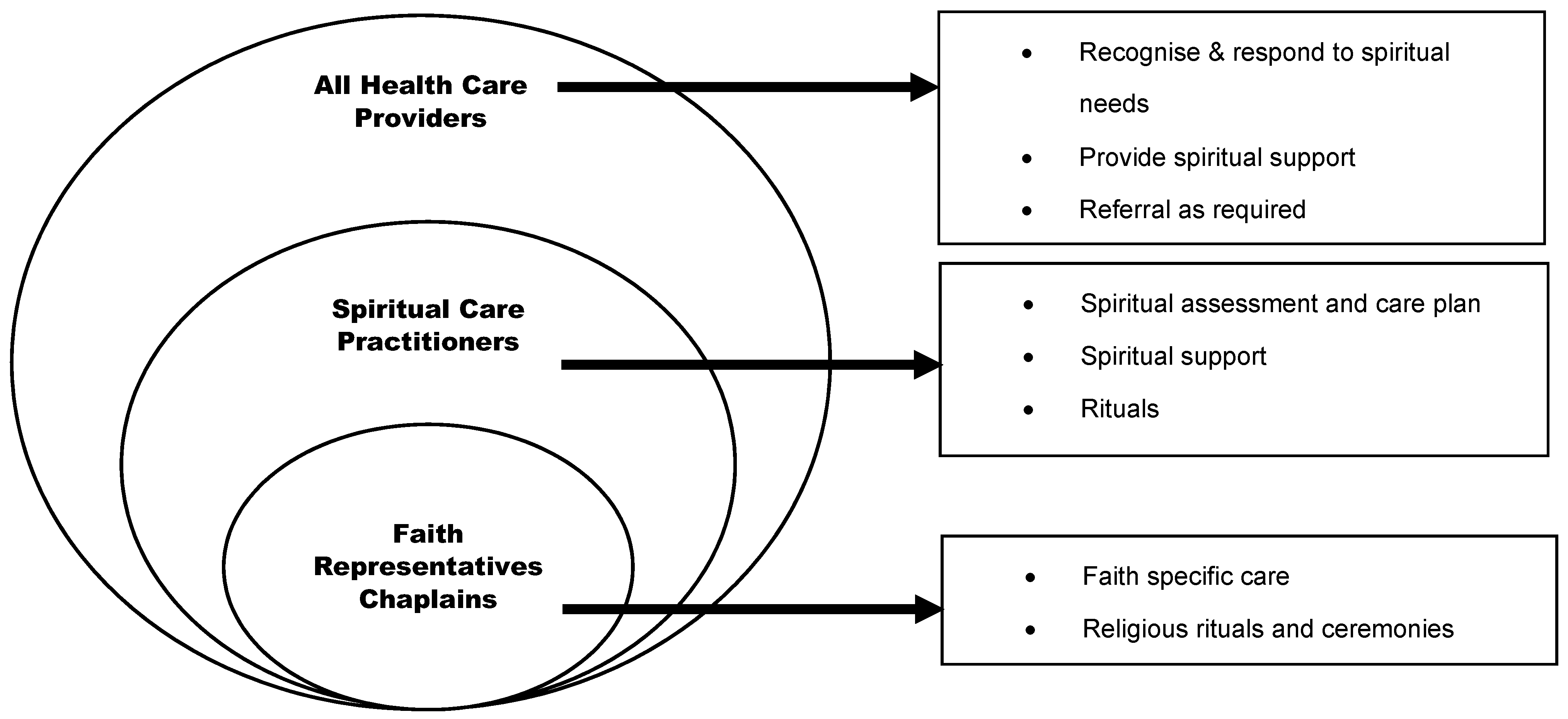

| 4. | Spiritual care is a shared responsibility. |

| 5. | Research is conducted on the contribution, value and effectiveness of spiritual care. |

| Policy Statements | |

|---|---|

| 1. | There is a paid professional spiritual/pastoral care workforce in hospitals. |

| 2. | All health professionals receive training about spiritual care. |

| 3. | All patients are offered the opportunity to have a discussion of their religious/spiritual concerns. |

| 4. | All patients have an assessment of their spiritual needs. |

| 5. | Patient’s values and beliefs are integrated into care plans. |

| 6. | Information gathered from assessments of spiritual needs is included in the patient’s overall care plan. |

| 7. | Families are given the opportunity to discuss spiritual issues with health professionals. |

| 8. | Faith communities are recognised as partners in the provision of spiritual care. |

| 9. | Spiritual care quality measures are included as part of the hospital’s quality of care reporting. |

| 10. | Hospitals provide a dedicated space for meditation, prayer, ritual or reflection. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holmes, C. Towards National Consensus: Spiritual Care in the Australian Healthcare Context. Religions 2018, 9, 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9120379

Holmes C. Towards National Consensus: Spiritual Care in the Australian Healthcare Context. Religions. 2018; 9(12):379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9120379

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolmes, Cheryl. 2018. "Towards National Consensus: Spiritual Care in the Australian Healthcare Context" Religions 9, no. 12: 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9120379

APA StyleHolmes, C. (2018). Towards National Consensus: Spiritual Care in the Australian Healthcare Context. Religions, 9(12), 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9120379