Spiritual Distress in Cancer Patients: A Synthesis of Qualitative Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

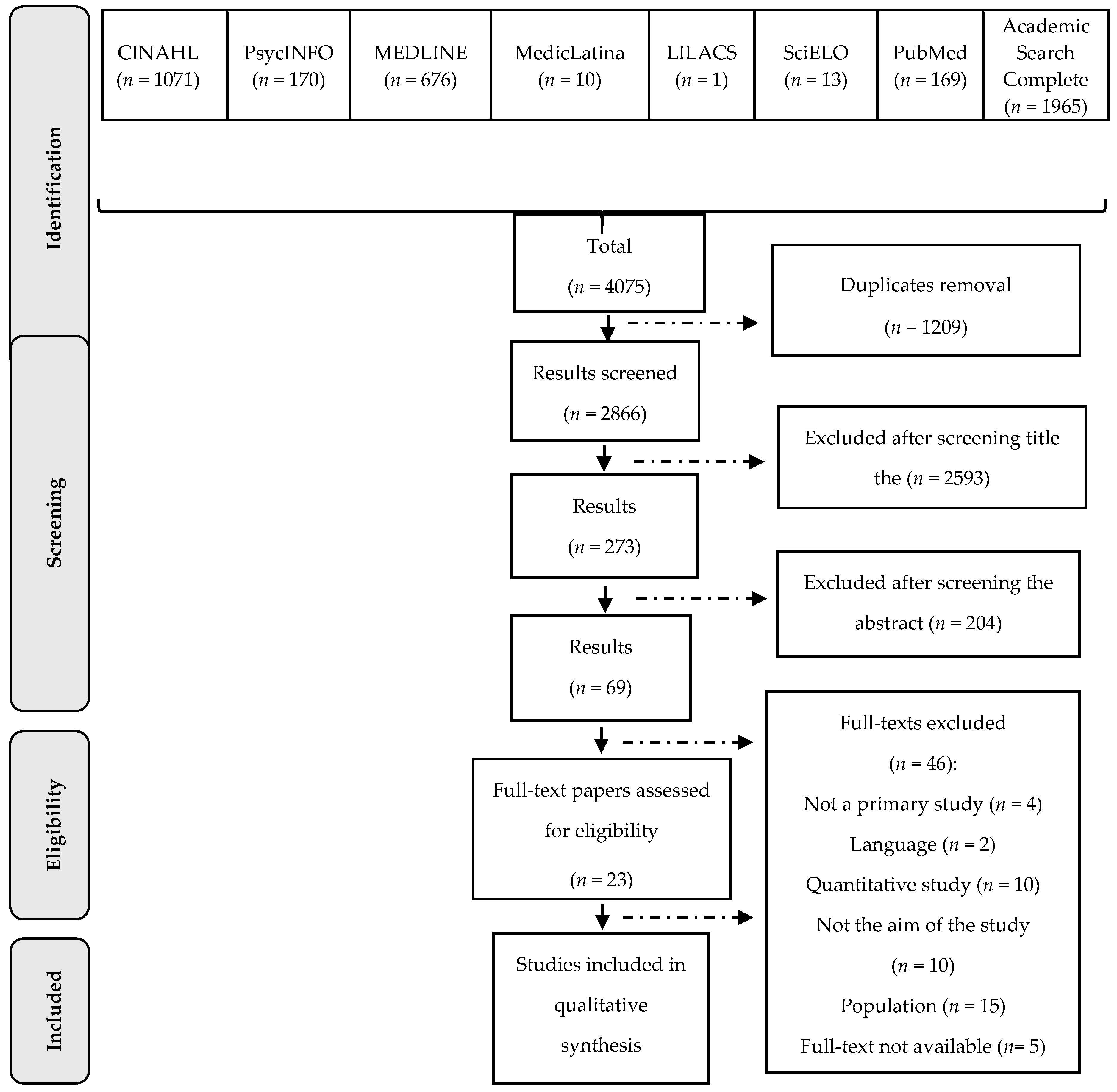

2. Materials and Methods

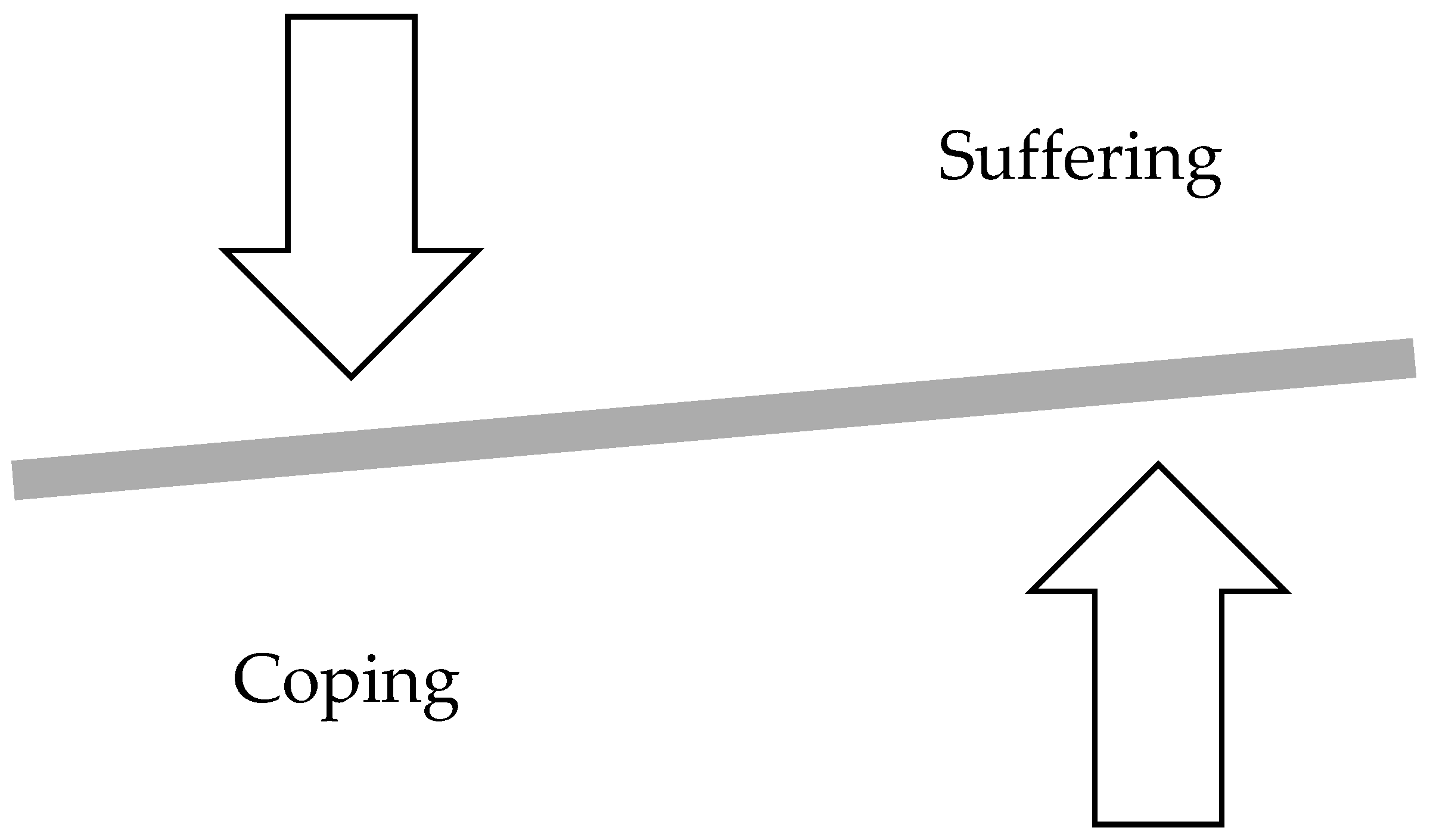

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albaugh, Jeffrey A. 2003. Spirituality and Life-Threatening Illness: A Phenomenologic Study. Oncology Nursing Forum 30: 593–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshenqeeti, Hamza. 2014. Interviewing as a Data Collection Method: A Critical Review. English Linguistics Research 3: 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. 2018. Cancer Facts & Figures 2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Asgeirsdottir, Gudlaug Helga, Einar Sigurbjörnsson, Rannveig Traustadottir, Valgerdur Sigurdardottir, Sigridur Gunnarsdottir, and Ewan Kelly. 2013. “To Cherish Each Day as it Comes”: A Qualitative Study of Spirituality Among Persons Receiving Palliative Care. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 21: 1445–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balboni, Michael J., Adam Sullivan, Andrea C. Enzinger, Zachary D. Epstein-Peterson, Yolanda D. Tseng, Christine Mitchell, Joshua Niska, Angelika Zollfrank, Tyler J. VanderWeele, and Tracy A. Balboni. 2014. Nurse and Physician Barriers to Spiritual Care Provision at the End of Life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 48: 400–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balducci, Lodovico. 2010. Beyond Quality of Life: The Meaning of Death and Suffering in Palliative Care. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP 11: 41–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barton-Burke, Margaret, Raimundo C. Barreto Jr., and Lisa I. S. Archibald. 2008. Suffering as a Multicultural Cancer Experience. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 24: 229–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, Alan T. 2016. Addressing Existential Suffering. British Columbia Medical Journal 58: 268–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bentur, Netta, Daphna Yaira Stark, Shirli Resnizky, and Zvi Symon. 2014. Coping Strategies for Existencial and Spiritual Suffering in Israeli Patients with Advanced Cancer. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research 3: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, Megan, Lynley Aldridge, Phyllis Butow, Ian Oliver, Melanie Price, and Fleur Webster. 2015. Assessment of Spiritual Suffering in the Cancer Context: A Systematic Literature Review. Palliative and Supportive Care 13: 1335–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blinderman, Craig D., and Nathan I. Cherny. 2005. Existential Issues Do Not Necessarily Result in Existential Suffering: Lessons from Cancer Patients in Israel. Palliative Medicine 19: 371–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeira, Sílvia, Emília Campos de Carvalho, and Margarida Vieira. 2013. Spiritual Distress-Proposing a New Definition and Defining Characteristics. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge 24: 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeira, Sílvia, Emília Campos de Carvalho, and Margarida Vieira. 2014. Between Spiritual Wellbeing and Spiritual Distress: Possible Related factors in Elderly Patients with Cancer. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem (RLAE) 22: 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeira, Sílvia, Fiona Timmins, Emília Campos de Carvalho, and Margarida Vieira. 2016. Nursing Diagnosis of “Spiritual Distress” in Women with Breast Cancer Prevalence and Major Defining Characteristics. Cancer Nursing 39: 321–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeira, Sílvia, Fiona Timmins, Emília Campos de Carvalho, and Margarida Vieira. 2017. Clinical Validation of the Nursing Diagnosis Spiritual Distress in Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge 28: 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, Linda, Maureen Angen, Jodi Cullum, Eillen Goodey, Jan Koopmans, Lisa Lamont, J.H. MacRae, M. Martin, Guy Pelletier, John Robinson, and et al. 2004. High Levels of Untreated Distress and Fatigue in Cancer Patients. British Journal of Cancer 90: 2297–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CASP. 2013. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available online: http://www.casp-uk.net/#!checklists/cb36 (accessed on 16 January 2018).

- Chao, Co-Shi Chantal, Ching-Huey Chen, and Miaofen Yen. 2002. The Essence of Spirituality of Terminally Ill Patients. Journal of Nursing Research (Taiwan Nurses Association) 10: 237–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, Erika de Cássia Lopes, Emília Campos de Carvalho, and Vanderlei José Hass. 2010. Validação do Diagnóstico de Enfermagem Angústia Espiritual: Análise por Especialistas. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem 23: 264–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chio, Chung-Ching, Fu-Jin Shih, Jeng-Fong Chiou, Hsiao-Wei Lin, Fei-Hsiu Hsiao, and Yu-Ting Chen. 2008. The Lived Experiences of Spiritual Suffering and the Healing Process among Taiwanese Patients with Terminal Cancer. Journal of Clinical Nursing 17: 735–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, Rhonda S. 2011. Case Study of a Chaplain’s Spiritual Care for a Patient with Advanced Metastatic Breast Cancer. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 17: 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coward, Doris Dickerson, and David L. Kahn. 2004. Resolution of Spiritual Disequilibrium by Women Newly Diagnosed with Breast Cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum 31: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Danhauer, Suzanne C., Sybil L. Crawford, Deborah F. Farmer, and Nancy E. Avis. 2009. A Longitudinal Investigation of Coping Strategies and Quality of Life Among Younger Women with Breast Cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 32: 371–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, Mellar P., Dilara Khoshknabi, Declan Walsh, Ruth Lagman, and Alexandra Platt. 2013. Insomnia in Patients with Advanced Cancer. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine 31: 365–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Guay, Marvin Omar, Henrique A. Parsons, David Hui, Maxine G. De la Cruz, Steven Thorney, and Eduardo Bruera. 2013. Spirituality, Religiosity, and Spiritual Pain among Caregivers of Patients with Advanced Cancer. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 30: 455–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfil, Mohamed, and Ahmed Negida. 2017. Sampling Methods in Clinical Research: An Educational Review. Emergency 5: E52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Exline, Julie J., Maryjo Prince-Paul, Briana L. Root, and Karen S. Peereboom. 2013. The Spiritual Struggle of Anger toward God: A Study with Family Members of Hospice Patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine 16: 369–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farsi, Zahra. 2015. The Meaning of Disease and Spiritual Responses to Stressors in Adults with Acute Leukemia Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Journal of Nursing Research 23: 209–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fife, Betsy. 2005. The Role of Constructed Meaning in Adaptation to the Onset of Life-Threatening Illness. Social Science & Medicine 61: 2132–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielen, Joris, Sushma Bhatnagar, and Santosh K. Chaturvedi. 2017. Prevalence and Nature of Spiritual Distress Among Palliative Care Patients in India. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 530–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, Giselle Patrícia, Márcia Maria Fontão Zago, Namie Okino Sawada, and Maria Helena Pinto. 2011. Relação Entre Espiritualidade e Câncer: Perspectiva do Paciente. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 64: 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilherme, Caroline, and Emília Campos de Carvalho. 2011. Spiritual Distress in Cancer Patients: Nursing Interventions. Journal of Nursing UFPE/Revista de Enfermagem UFPE 5: 290–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, Maria, Gerald M. Devins, and Gary M. Rodin. 2002. Stress Response Syndromes and Cancer: Conceptual and Assessment Issues. Psychosomatics 43: 259–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajdarevic, Senada, Birgit H. Rasmussen, and Åsa Hörnsten. 2014. You Never Know When Your Last Day Will Come and Your Trip Will Be Over—Existential Expressions from a Melanoma Diagnosis. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 18: 355–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halstead, Marilyn Tuls, and Margaret Hull. 2001. Struggling with Paradoxes: The Process of Spiritual Development in Women with Cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum 28: 1534–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Herdman, Heather T., and Shigemi Kamitsuru, eds. 2018. NANDA: NANDA International Nursing Diagnoses: Definitions and Classification 2018–2010, 11th ed. Chichester/Ames: Wiley-Blackwell, 512p. First published 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, David, Maxine de la Cruz, Steve Thorney, Henrique A. Parsons, Marvin Delgado-Guay, and Eduardo Bruera. 2011. The Frequency and Correlates of Spiritual Distress Among Patients with Advanced Cancer Admitted to an Acute Palliative Care Unit. The American journal of Hospice & Palliative Care 28: 264–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kawa, Masako, Mami Kayama, Etsuko Maeyama, Noriko Iba, Hisayuki Murata, Yuka Imamura, Tikayo Koyama, and Michiyo Mizuno. 2003. Distress of Inpatients with Terminal Cancer in Japanese Palliative Care Units: From the Viewpoint of Spirituality. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 11: 481–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodaveirdyzadeh, Roghieh, Rabee Rahimi, Azad Rahmani, Akram Ghahramanian, Naser Kodayari, and Jamal Eivazi. 2016. Spiritual/Religious Coping Strategies and Their Relationship with Illness Adjustment among Iranian Breast Cancer Patients. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 17: 4095–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ku, Ya-Lie, Shih-Ming Kuo, and Ching-Yi Yao. 2010. Establishing the Validity of a Spiritual Distress Scale for Cancer Patients Hospitalized in Southern Taiwan. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 16: 134–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindholm, Lisbet, Arne Rehnsfeldt, Maria Arman, and Elisabeth Hamrin. 2002. Significant Others’ Experience of Suffering When Living with Women with Breast Cancer. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 16: 248–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, Ken Yin. 2004. Spiritual Distress in a Terminally Ill Patient with Breast Cancer. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 10: 131–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, Helga, Joana Romeiro, and Sílvia Caldeira. 2017. Spirituality in Nursing: An Overview of Research Methods. Religions 8: 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, Pam. 2002. Creating a Language for “Spiritual Pain” Through Research: A Beginning. Support Care Cancer 10: 637–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monod, Stefanie, Estelle Martin, Brenda Spencer, Etienne Rochat, and Christophe Bula. 2012. Validation of the Spiritual Distress Assessment Tool in Older Hospitalized Patients. BioMed Central Geriatrics 12: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya-Juarez, Rafael, María Paz Garcia-Caro, Concepcion Campos-Calderon, Jacqueline Schmidt-RioValle, Antonio Gomez-Chica, Celia Marti-García, and Francisco Cruz-Quintana. 2013. Psychological Responses of Terminally Ill Patients Who Are Experiencing Suffering: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 50: 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, Lucila Castanheira, Fabiane Cristina Santos de Oliveira, Moisés Fargnolli Moreno, and Fernanda Machado da Silva. 2010. Spiritual Care: An Essential Component of the Nurse Practice in Pediatric Oncology. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem 23: 437–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilmanat, Kittikorn, Pachariya Chailungka, Temsak Phungrassami, Chantra Promnoi, Kandawasri Tulathamkit, Prachuap Noo-urai, and Sasiwimon Phattaranavig. 2015. Moving Beyond Suffering: The Experiences of Thai Persons with Advanced Cancer. Cancer Nursing 38: 224–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyatanga, Brian. 2014. Supporting Patients in Coping with Cancer. British Journal of Community Nursing 19: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, Eileen, Paul D’Alton, Conor O’Malley, Finola Gill, and Áine Canny. 2013. The Distress Thermometer: A Rapid and Effective Tool for the Oncology Social Worker. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance 26: 353–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- des Ordons, Amanda Roze, Tasnim Sinuff, Henry T. Stelfox, Jane Kondejewski, and Shane Sinclair. 2018. Spiritual Distress within Inpatient Settings—A Scoping Review of Patient and Family Experiences. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 56: 122–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perreault, Annie, and Frances Fothergill Bourbonnais. 2005. The Experience of Suffering as Lived by Women with Breast Cancer. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 11: 510–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, Denise F., and Cheryl Tatano Beck. 2014. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 533p. First published 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rahnama, Mozhgan, Masoud Fallahi Khoshknab, Sadat Seyed Bagher Maddah, and Fazlollah Ahmadi. 2012. Iranian Cancer Patients’ Perception of Spirituality: A Qualitative Content Analysis Study. Bio Med Central Nursing 11: 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rushton, Lucy. 2014. What are the Barriers to Spiritual Care in a Hospital Setting? British Journal of Nursing 23: 370–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renz, Monika, Miriam Schütt Mao, Aurelius Omlin, Daniel Bueche, Thomas Cerny, and Florian Strasser. 2015. Spiritual Experiences of Transcendence in Patients with Advanced Cancer. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine 32: 178–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydé, Kerstin, Maria Friedrichsen, and Peter Strang. 2007. Crying: A Force to Balance Emotions Among Cancer Patients in Palliative Home Care. Palliative and Supportive Care 5: 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, Rosana F., and Marisa Cotta Mancini. 2007. Estudos de Revisão Sistemática: Um Guia Para Síntese Criteriosa da Evidência Científica. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy 11: 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, H. 2000. Meeting the Information Needs of Cancer Patients. Professor Nurse 15: 244–47. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, Fu-Jin, Hung-Ru Lin, Meei-Ling Gau, Ching-Huey Chen, Szu-Mei Hsiao, Shaw-Nin Shih, and Shuh-Jen Sheu. 2009. Spiritual Needs of Taiwan’s Older Patients with Terminal Cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum 36: 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorten, Allison, and Calvin Moorley. 2014. Selecting the Sample. Evidence-Based Nursing 17: 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, Rebecca L., Kimberly D. Miller, and Ahmedin Jemal. 2018. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 68: 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, Talita Prado, Erika de Cássia Lopes Chaves, and Denise Hollanda Iunes. 2015. Angústia Espiritual: A Busca Por Novas Evidências. Revista de Pesquisa: Cuidado é Fundamental Online 7: 2591–92. [Google Scholar]

- Skalla, Karen A., and Betty Ferrell. 2015. Challenges in Assessing Spiritual Distress in Survivors of Cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing 19: 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, Jane, and Zubin Austin. 2015. Qualitative Research: Data Collection, Analysis, and Management. The Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 68: 226–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiew, Lay Hwa, Kwee Jian Hui, Debra K. Creedy, and Moon Fai Chan. 2013. Hospice Nurses’ Perspectives of Spirituality. Journal of Clinical Nursing 22: 2923–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmins, Fiona, and Sílvia Caldeira. 2017. Assessing the Spiritual Needs of Patients. Nursing Standard 31: 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre, Lindsey A., Rebecca L. Siegel, Elizabeth M. Ward, and Ahmedin Jemal. 2016. Global. Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates and Trends—An Update. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 25: 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagomeza, Liwliwa R. 2005. Spiritual Distress in Adult Cancer Patients: Toward Conceptual Clarity. Holistic Nursing Practice 19: 285–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrinten, Charlotte, Lesley M. McGregor, Małgorzata Heinrich, Christian von Wagner, Jo Waller, Jane Wardle, and Georgia B. Black. 2017. What Do people Fear About Cancer? A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis of Cancer Fears in the General Population. Psycho-Oncology 26: 1070–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wein, Simon. 2011. Impact of Culture on the Expression of Pain and Suffering. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology 33: S105–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. 2014. World Cancer Report. Geneva: World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 630p. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Beverly Rosa. 2004. Dying Young, Dying Poor: A Sociological Examination of Existential Suffering Among Low-Socioeconomic Status Patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine 7: 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, Barbara J. 2012. Self-Transcendence in Stem Cell Transplantation Recipients: A Phenomenologic Inquiry. Oncology Nursing Forum 39: 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, Keith G., Harvey Max Chochinov, Christine J. McPherson, Katerine LeMay, Pierre Allard, Srini Chary, Pierre R. Gagnon, Karen Macmillan, Marina De Luca, Fiona O’Shea, and et al. 2007. Suffering with Advanced Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 25: 1691–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilt, Joshua A., Joshua B. Grubbs, Kenneth I. Pargament, and Julie J. Exline. 2016. Religious and Spiritual Struggles, Past and Present: Relations to the Big Five and Well-Being. The International International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 27: 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Hua. 2018. Coping: A concept analysis in the cancer context. TMR Integrative Nursing 2: 27–33. [Google Scholar]

| Search | CINAHL | PsycINFO | MEDLINE | MedicLatina | LILACS | SciELO | PubMed | Academic Search Complete |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S#1: Cancer patients | 86,404 | 19,640 | 284,290 | 1878 | 11,357 | 6845 | 142,010 | 372,783 |

| S#2: Cancer survivors | 20,721 | 4981 | 24,316 | 496 | 206 | 121 | 11,429 | 75,480 |

| S#3: Cancer survivorship | 4363 | 1431 | 5277 | 17 | 530 | 28 | 1602 | 5534 |

| S#4: Malignant tumor | 11,861 | 887 | 26,303 | 919 | 12,394 | 1451 | 11,593 | 125,431 |

| S#5: Neoplasms | 453,778 | 61,404 | 2,421,031 | 12,346 | 51,470 | 6019 | 2,389,420 | 978,080 |

| S#6: Oncologic patients | 557 | 96 | 2117 | 56 | 663 | 387 | 999 | 3402 |

| S#7: Oncology patients | 6686 | 1517 | 10,738 | 137 | 1273 | 848 | 3839 | 29,090 |

| S#8: Tumors | 453,778 | 61,404 | 825,969 | 12,346 | 24,997 | 5529 | 539,098 | 978,080 |

| S#9: Spiritual distress | 821 | 285 | 614 | 4 | 23 | 30 | 236 | 1526 |

| S#10: Spiritual suffering | 322 | 179 | 232 | 6 | 90 | 89 | 67 | 2366 |

| S#11: Spiritual anguish | 21 | 6 | 17 | 0 | 24 | 11 | 14 | 387 |

| S#12: Spiritual pain | 285 | 183 | 220 | 2 | 67 | 67 | 70 | 1942 |

| S#13: Spiritual struggle | 239 | 275 | 117 | 1 | 2 | 25 | 41 | 3579 |

| S#14: Existential pain | 78 | 86 | 86 | 0 | 27 | 20 | 26 | 556 |

| S#15: Existential suffering | 523 | 173 | 370 | 5 | 75 | 54 | 107 | 1120 |

| S#16: (S#1 OR S#2 OR S#3 OR S#4 OR S#5 OR S#6 OR S#7 OR S#8) | 494,166 | 64,417 | 2,730,412 | 13,206 | 55,379 | 14,991 | 2,543,359 | 1,143,746 |

| S#17: (S#9 OR S#10 OR S#11 OR S#12 OR S#13 OR S#14 OR S#15) | 2031 | 1088 | 1505 | 16 | 220 | 89 | 533 | 10,120 |

| S#18: (S#16 AND S#17) | 1071 | 170 | 676 | 10 | 1 | 13 | 169 | 1965 |

| Major Theme | Sub-Theme | Citation/Example | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suffering | Alienation | “Being empty and in a vacuum is a feeling of becoming bare, “empty in the head”, experiencing difficulty in thinking and living”Hajdarevic et al. (2014, p. 3) | Hajdarevic et al. (2014); McGrath (2002); Nilmanat et al. (2015) |

| Suffering | Anger | “I am very angry”Loh (2004, p. 131) | Asgeirsdottir et al. (2013); Chio et al. (2008); Loh (2004); Nilmanat et al. (2015) |

| Suffering | Anxiety | “The evening I heard my diagnosis I immediately went to a friend’s house for the night. The next night I started feeling very anxious and I called a friend in California”Coward and Kahn (2004, p. E2) “I had a problem with that. I was more anxious” Williams (2012, p. E44) | Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chio et al. (2008) Cooper (2011); Coward and Kahn (2004); Halstead and Hull (2001); Kawa et al. (2003); Lindholm et al. (2002); Nilmanat et al. (2015); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Williams (2012) |

| Suffering | Body image | “Think the loss of my hair is a major issue for me still, and just because every day you look in the mirror and you see that I’ve had leukemia. It is a constant reminder, smack bang in my face. And so I still find that extremely hard to deal with” McGrath (2002, p. 640) ‘I felt mutilated even if I still had my breast … I’ve got a hole.’ Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005, p. 515) | Bentur et al. (2014); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Hajdarevic et al. (2014); Halstead and Hull (2001); Kawa et al. (2003); McGrath (2002); Nilmanat et al. (2015); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Shih et al. (2009) |

| Suffering | Burden to family | “I think I may feel happier and feel free if I die early. I do not want to be tortured any more. I am very tired of having this kind of life. My children are very kind. But I wish to die early so as not to be their burden” Chio et al. (2008, p. 740) “He [her husband] saw that I had been crying, and then I said to him to be sure that he knew, that the day I cannot take care of myself I want to be cared for in a hospice, and that the family should not devote all their time to caring for me, and quite soon I felt how focus on the future came much closer to me” (Hajdarevic et al. 2014, p. 4) | Asgeirsdottir et al. (2013); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chao et al. (2002); Chio et al. (2008); Hajdarevic et al. (2014); Kawa et al. (2003); Lindholm et al. (2002); Nilmanat et al. (2015); Shih et al. (2009); Williams (2004) |

| Suffering | Crying | “You know when I last cried? About a week ago a couple came in here. I didn’t see the man, he stood behind the curtain. The woman was handsome, tall. She held a basket …. My son was hospitalized here for some time, he passed away. These sweets are in memoriam’. [Weeping] I started crying, that’s beautiful!”Bentur et al. (2014, p. 6) “Felt withdrawn … (crying) … the pain is the scariest thing” Nilmanat et al. (2015, p. 395) | Bentur et al. (2014); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chio et al. (2008); Hajdarevic et al. (2014); Nilmanat et al. (2015); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005) |

| Suffering | Disconnected | “I feel disconnected”Halstead and Hull (2001, p. 1538) | Halstead and Hull (2001); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Coward and Kahn (2004); McGrath (2002); Williams (2004); Williams (2012) |

| Suffering | Fatalism | “The main change is that you see you are dying in a more realistic way” Montoya-Juarez et al. (2013, p. 56) “I’m already in the coffin and they can come to the funeral home and look at me like I’m on display or something” Williams (2004, p. 35) “But we always talk about everyday things and we don’t talk about life. We pushed life aside.” Bentur et al. (2014, p. 3) | Bentur et al. (2014); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Halstead and Hull (2001); Kawa et al. (2003); Lindholm et al. (2002); Montoya-Juarez et al. (2013); Lindholm et al. (2002); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Rahnama et al. (2012); Shih et al. (2009); Williams (2004); Williams (2012) |

| Suffering | Fear | “I’m not ready to die … I’m afraid … When you die, you must say goodbye to your children … your spouse, friends and family, you must say goodbye to your roles and dreams …” Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005, p. 517) “I did start experiencing fear, and I would have moments of doubt” Halstead and Hull (2001, p. 1539) | Asgeirsdottir et al. (2013); Balducci (2010); Bentur et al. (2014); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chio et al. (2008); Cooper (2011); Coward and Kahn (2004); Halstead and Hull (2001); Kawa et al. (2003); Lindholm et al. (2002); Nilmanat et al. (2015); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Williams (2004); Williams (2012) |

| Suffering | Forgiveness | “If you don’t have the feeling of hatred, then you can easily forgive others, no matter what has happened” Rahnama et al. (2012, p. 4) | Chao et al. (2002); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Rahnama et al. (2012) |

| Suffering | Good death/Desire to die | “I have been tolerating pain for a long time. In this torturing process, I with this tortured body have been through a difficult time. I feel very painful. If I could die early, I would not experience the torture anymore”Chio et al. (2008, p. 739) | Chio et al. (2008); Kawa et al. (2003); Nilmanat et al. (2015) |

| Suffering | Guilt/Punishment | “I feel so bad about all of this. Everyone knows it’s my fault, but I can’t help it. I knew it was coming one day. I’ve been looking for it for years, smoking and all, being a mechanic and all. I won’t be around to see them grow up because of something I did to myself”Williams (2004, p. 32) “I knew that, although I had tried not to commit any sins, I had committed some. After suffering cancer, I thought that this disease is a punishment from God and I was happy to accept this” Farsi (2015, p. 4) | Balducci (2010); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chao et al. (2002); Chio et al. (2008); Cooper (2011); Farsi (2015); Hajdarevic et al. (2014); Halstead and Hull (2001); Williams (2004) |

| Suffering | Hopelessness | “Disability problems caused by the immobility of her legs led her to feel despair and hopelessness”Chio et al. (2008, p. 740) “It’s worse not to know you have cancer and it’s eating you away and suddenly you have no hope…” Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005, p. 516) | Chio et al. (2008); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); McGrath (2002) |

| Suffering | Impaired role performance | “Actually I miss them so much. I am unable to care them anymore”Loh (2004, p. 131) “The other problem is that I leave my children here and they have no one. My children don’t have anyone to fry an egg for them” Montoya-Juarez et al. (2013, p. 57) | Bentur et al. (2014); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chao et al. (2002); Kawa et al. (2003); Loh (2004); McGrath (2002); Montoya-Juarez et al. (2013); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Williams (2004) |

| Suffering | Insomnia | “I mean, I couldn’t sleep, I couldn’t do anything”Williams (2012, p. E43) | Nilmanat et al. (2015); Williams (2012) |

| Suffering | Lack of autonomy/dignity | “It is very difficult. I feel like I am in prison. I walk around with my nephrostomy bag. My body does not function well”Blinderman and Cherny (2005, p. 374) “Hope that they would treat me not as an invalid like’s it’s something catching. (Williams 2004, p. 34) | Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chio et al. (2008); Kawa et al. (2003); Montoya-Juarez et al. (2013); Nilmanat et al. (2015); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Williams (2004) |

| Suffering | Feeling abandoned (by relatives and friends) | “They took my money. But they do not take care of me” Chio et al. (2008, p. 739) | Chio et al. (2008); McGrath (2002); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005) |

| Suffering | Loneliness | “I am weak, alone. I don’t care”Blinderman and Cherny (2005, p. 374) “I live every day knowing that my cancer is going to come back. It’s a very lonely thing; it’s very difficult. Some days you can handle it, some days you can’t” Williams (2012, p. E46) “I feel lonely and scared because of my declining health (during the evening and night in particular)” Shih et al. (2009, p. E34) | Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Cooper (2011); Hajdarevic et al. (2014); Kawa et al. (2003); Lindholm et al. (2002); McGrath (2002); Shih et al. (2009); Williams (2012) |

| Suffering | Questioning identity | “… And I needed to talk and talk and talk and talk and talk. Until it got to the stage where I had lost my identity”McGrath (2002, p. 642) | McGrath (2002); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005) |

| Suffering | Physical symptoms | “I keep vomiting. If I did not have the urge to vomit, I would be able to walk without having to ask for help from others … [I] just wish that I would not need to vomit, so I could walk and care for myself”Rahnama et al. (2012, p. 397) “I had so much phlegm I could hardly breathe half the time. I was a wreck physically, destroyed …” Williams (2012, p. E43) | Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chio et al. (2008); Farsi (2015); Kawa et al. (2003); McGrath (2002); Nilmanat et al. (2015); Rahnama et al. (2012); Shih et al. (2009); Williams (2012); Williams (2004) |

| Suffering | Refuses to interact with significant other | “They are fine. All of them are in school. I told them not to come” Loh (2004, p. 131) | Loh (2004) |

| Suffering | Relationship with God | “At first I was angry at God”Blinderman and Cherny (2005, p. 376) | Blinderman and Cherny (2005) |

| Suffering | Social isolation | “Yes, I felt socially isolated. I didn’t feel like leaving my home or speaking with others for months”Blinderman and Cherny (2005, p. 375) “I fear going out … [I am] not strong … [I am afraid of] getting infected … [I] just sit here (at the window), look at other people outside. Others are good [healthy] … can walk about and work, but I hide in the house. I cannot do anything … (sigh) … and think why it has to be me who is in this condition” Nilmanat et al. (2015, p. 396) “I don’t talk to many people any more. I don’t hang around with the same friends and everything. My mother is gone and I’m not that close to my daddy. I haven’t kept in touch with any of my high school friends, so I guess it would be hard to find out” Williams (2004, p. 34) | Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Kawa et al. (2003); Nilmanat et al. (2015); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Williams (2004) |

| Suffering | Uncertain future | “In the present situation, I am not healthy. It is true … I cannot talk about my future, because my physical condition tomorrow is unknown” Kawa et al. (2003, p. 484) | Coward and Kahn (2004); Hajdarevic et al. (2014); Halstead and Hull (2001); Kawa et al. (2003); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Williams (2004); Williams (2012) |

| Suffering | Worthlessness | “I am not afraid of losing my dignity. There is not much to lose” Blinderman and Cherny (2005, p. 375) | Blinderman and Cherny (2005) |

| Coping | Connection with family/friends/self/spirituality/religion | “Connect with friends on an intellectual level” Blinderman and Cherny (2005, p. 376) “Doris reported that these rituals helped her feel connected to God, and that she felt supported and comforted by both priests’ visits” Cooper (2011, p. 29) | Asgeirsdottir et al. (2013); Bentur et al. (2014); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Cooper (2011); Coward and Kahn (2004); Halstead and Hull (2001); Kawa et al. (2003); Lindholm et al. (2002); Rahnama et al. (2012); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Williams (2012) |

| Coping | Connection to body and mind | “If the nausea comes, I fight it. You’re not going to vomit, no, no! I hold the vomit back and it hurts in my chest to hold it back. If I’m in a good mental and emotional state, I can hold it in.” (Bentur et al. 2014, p. 4) “Once I am calm, I can tolerate my physical problems more easily” Rahnama et al. (2012, p. 5) “My mental health is connected to my physical health” Blinderman and Cherny (2005, p. 376) | Bentur et al. (2014); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chio et al. (2008); Rahnama et al. (2012) |

| Coping | Hope | “I’ve got hope because I’m still alive”Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005, p. 516) | Asgeirsdottir et al. (2013); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chao et al. (2002); Cooper (2011); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005) |

| Coping | Helping other patients | “We met in the hospital. Then, we encouraged each other and made fun of each other, which made us feel better”Chio et al. (2008, p. 740) “O yes, I still have the potential to help people, to make their lives a little better” Cooper (2011, p. 25) | Chao et al. (2002); Chio et al. (2008); Cooper (2011) |

| Coping | Non-spiritual/religious therapies/practices | “I’ve read since the transplant, you know, I’ve had a lot of time to read …. There is so much, you know, with New Age thinking and esoteric thinking and all that sort of thing, that I can’t make up my mind [laughs]. But I enjoy reading about it, it’s very interesting.” McGrath (2002, p. 239) | Asgeirsdottir et al. (2013); Balducci (2010); Bentur et al. (2014); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chao et al. (2002); Chio et al. (2008); Cooper (2011); Hajdarevic et al. (2014); Halstead and Hull (2001); McGrath (2002); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005) |

| Coping | Re-meaning | “Life has become for me a privileged experience of being in love. To love people surrounding me … to enjoy every moment … It’s to choose, not to endure, but to choose”Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005, p. 517) | Albaugh (2003); Balducci (2010); Bentur et al. (2014); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Cooper (2011); Hajdarevic et al. (2014); Halstead and Hull (2001); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005) |

| Coping | Spiritual practices | “I believe very strongly in the power of prayer, and I feel that everybody that is praying for me … everybody who talked to me either when they’re at church or friends around me, I thought that was wonderful … A prayer is like a gigantic hug from a number of people, all the people that tell me that they prayed for me. It’s just something that encompasses me, a good positive feeling that lifts me” Albaugh (2003, p. 595) | Albaugh (2003); Asgeirsdottir et al. (2013); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chio et al. (2008); Cooper (2011); Hajdarevic et al. (2014); Halstead and Hull (2001); Loh (2004); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Rahnama et al. (2012) |

| Coping | Support from family/friends | “My son had told his wife: May family has a great influence on my morale. I didn’t lose my heart because my mom and others treated me very well”Rahnama et al. (2012, p. 5) “I couldn’t make a decision on therapy options without the help of my family and friends. Without them, I just wanted to die immediately” Shih et al. (2009, p. E34) | Bentur et al. (2014); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chio et al. (2008); Hajdarevic et al. (2014); Halstead and Hull (2001); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Rahnama et al. (2012); Shih et al. (2009) |

| Coping | Support from healthcare professionals | “A psychologist often came to see me. I could release the pressure suppressed in my mind through talking and communicating with him. For example, a while ago, one patient who was my roommate in the hospital died. Two days later, another one died. I felt so scared. He took me to the living room and talked to me. After talking with him, I felt better”Chio et al. (2008, p. 740) “With the nurse’s encouragement, my children told me that they needed me so much. I know it is difficult for us Taiwanese to say so. As a dying person, I’m so content and this has reaffirmed my strong sense of belonging” Shih et al. (2009, p. E35) | Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chao et al. (2002); Chio et al. (2008); Shih et al. (2009) |

| Coping | Transcendence | “There is just something that is greater than you. You are not under its control or anything like that. There is some power that is higher than you, which I want to call a good one; a force that helps you in your daily difficulties and duties” Asgeirsdottir et al. (2013, p. 1449) | Asgeirsdottir et al. (2013); Coward and Kahn (2004); Chio et al. (2008); Farsi (2015); Shih et al. (2009); Williams (2012) |

| Coping | Transformation | “I guess I would say that a life-threatening thing happening to you is not the worst thing that can happen to you, it can make you a better person”Albaugh (2003, p. 597) | Albaugh (2003); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005) |

| Coping | Trust in God/Spiritual beliefs | “I was upset, but I didn’t claim it. I put it into God’s hands.” Ciele said, “I really gave it all over to God: ‘I don’t know what to do, but I trust that you will help me figure it out”Coward and Kahn (2004, p. E4) “Religious support has been like cool drink of water and a crutch to help me on my daily walk through the desert” Shih et al. (2009, p. E35) | Albaugh (2003); Bentur et al. (2014); Blinderman and Cherny (2005); Chao et al. (2002); Chio et al. (2008); Cooper (2011); Coward and Kahn (2004); Farsi (2015); Hajdarevic et al. (2014); Halstead and Hull (2001); Loh (2004); Perreault and Bourbonnais (2005); Rahnama et al. (2012); Shih et al. (2009) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martins, H.; Caldeira, S. Spiritual Distress in Cancer Patients: A Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Religions 2018, 9, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100285

Martins H, Caldeira S. Spiritual Distress in Cancer Patients: A Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Religions. 2018; 9(10):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100285

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartins, Helga, and Sílvia Caldeira. 2018. "Spiritual Distress in Cancer Patients: A Synthesis of Qualitative Studies" Religions 9, no. 10: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100285

APA StyleMartins, H., & Caldeira, S. (2018). Spiritual Distress in Cancer Patients: A Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Religions, 9(10), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9100285