1. Introduction

Between 1982 and 2001, the number of Catholic, Protestant, and Islamic affiliates increased from 10 million to 60 million in China. The nonstatistical affiliates of Buddhism and Daoism are about 10 million in number. The white paper on religious belief in China (Baipishu) shows that there are 100 million people in China who believe in religion. Related statistics are debatable as some suggest that 300 million followers of religion is a more approximate number. According to surveys, 70–80 percent of the affiliates began to convert from the 1980s onwards, and of them 30 percent are young people [

1]. As Professor Fenggang Yang observed: “In the reform era since 1979, all kinds of religions have revived and are thriving. Christianity has been the fastest-growing religion for decades” [

2]. Published estimates of the proportion of Christians in the Chinese population range from approximately 1 percent in some relatively small-sample public opinion surveys to about 8 percent in reviews of membership reports from churches and church leaders (including unregistered churches) within China. The Pew Forum’s demographers estimate that the 2010 Christian proportion of China’s population is likely to be approximately 5 percent (or 67 million people of all ages). This figure includes non-adult children of Chinese affiliates and unbaptized people who attend Christian worship services [

3]. What about young people’s religious faith, or college students’ faith? In the early 2000s, one-third of the population with religious beliefs were young people, which is around 30–40 million [

4]. As part of the religious revival since the Reform era, Christianity has gained popularity in China. An increasing number of people have become Christians, especially in coastal towns and developed cities.

How common is Christianity among the young people in universities, especially in Xi’an, a city in Northwestern China? To answer this question, we conducted a survey aiming to learn the basic trends in the percentage of Christians among college students and their attitudes toward Christianity. We asked all participants about how they came to know about Christianity. Was it the church or other Christians that led them to develop an awareness and understanding of Christianity? Among the affiliates, we asked them when they started believing in the Christian message and why. Additionally, we questioned them on how their religious practices take place on campus. How do they get exposed to the Christian faith on campus? How do they spread their knowledge of Christianity to other students?

To gain answers to these questions, we randomly selected 1000 students from 12 universities in Xi’an. The universities were selected for their different specialties including liberal arts, science, and language studies. The selected universities are distributed in different parts of the city. Since the sample is randomly selected, we hoped to balance the ratio between male and female participants; the grade ranges were from freshman to graduate students; and the ethnic groups comprised both Han and minorities. This general survey aimed to understand the religious beliefs of college students and to find out if Christianity was popular on campus.

The questionnaires were distributed twice to students on campus, and they had to fill them in during classes. First, when 250 students were pre-tested, we found that some questions that were based on previous questionnaires did not get clear answers, and we made additions and changed some of them. Then, later we distributed 750 changed questionnaires. Therefore, the total number of statistics had little variation for the different questions. We received 950 questionnaires in return, for a 95 percent response rate. The following are the results of the statistical analysis of 950 questionnaires. SPSS was used for data analysis.

2. Religious Affiliation in China

A number of studies have already investigated religious affiliation in China generally. For example, Stark and Wang find that Christianity is widespread in China, with the rate of Chinese claiming affiliation rising in recent decades [

5]. However, these scholars also find that there is a general reluctance of many Chinese to admit affiliation with Christianity. In this sense, claiming affiliation is still a relatively undesirable status socially. They find that many Chinese have a personal faith in Christianity but tend to underreport more public forms of religiosity, such as affiliation with a specific religious tradition.

Less studied is the extent to which this broader pattern in China is true among young Chinese. In particular, religiosity among college students is important for predicting future patterns in China. However, no studies that we are aware of have given particular attention to religious affiliation among college students, especially not in Xi’an. Xi’an is located in the interior of the country and as a “university city” has a large concentration of universities. Thus, this study has particular relevance.

3. Survey in Xi’an, China

3.1. Student Characteristics

We selected different universities in Xi’an to distribute the questionnaires to get a varied sample with regard to gender, grade, major, and nationality. However, students were not chosen on the basis of any specific characteristic.

Gender: The total number of valid questionnaires was 950, of which 364 were male respondents, 562 female, and 24 non-indicated, accounting for 38.3 percent, 59.2 percent, and 2.5 percent, respectively. The proportion of girls was relatively high, which corresponded with the overall proportion of girls in the universities.

Grade: Of the students who answered the questionnaire, 155 were postgraduates, 782 undergraduates, 2 college students, and 11 undesignated, accounting for 16.3 percent, 82.3 percent, 0.2 percent, and 1.2 percent, respectively. Most of the respondents were undergraduates, showing that they formed the main group among college students.

Majors: The numbers of students majoring in different disciplines were as follows: In the arts, there were 317 students majoring in humanities and social sciences, 139 in foreign languages, and 8 in art and sports. This comes to a total of 464 students, which accounts for 48.8 percent of the sample. In addition, there were 428 students majoring in science and engineering, and 46 majoring in medicine, with a combined total of 474 students comprising 49.9 percent of the sample. Finally, there were 12 students without a designated major who comprised 1.3 percent of the sample of college students in this study.

Minorities and Han: The number of students from among the Han nationality, minorities, and the undesignated were 823, 121, and 6, accounting for 86.6 percent, 12.7 percent, and 0.6 percent, respectively. This reflects the overall situation in the country. The number of students among minorities was slightly higher because some surveys were concentrated in minorities’ classes.

These randomly selected students reflect the overall trends among college students in Xi’an, and the different variables in the sample were conducive to a representative survey.

3.2. Students’ Faith Profiles

Other researchers who surveyed the number of college students who affiliate with religions showed results with the proportion of affiliates varying from 3.5 percent to 44 percent. A higher proportion of college students was found in the coastal region, underdeveloped areas, and minority areas who affiliated with a religion. [

1] Xi’an is not a coastal region, nor is it underdeveloped, nor is it in the minority area; thus, we know little about the proportion of students who affiliate with religion there.

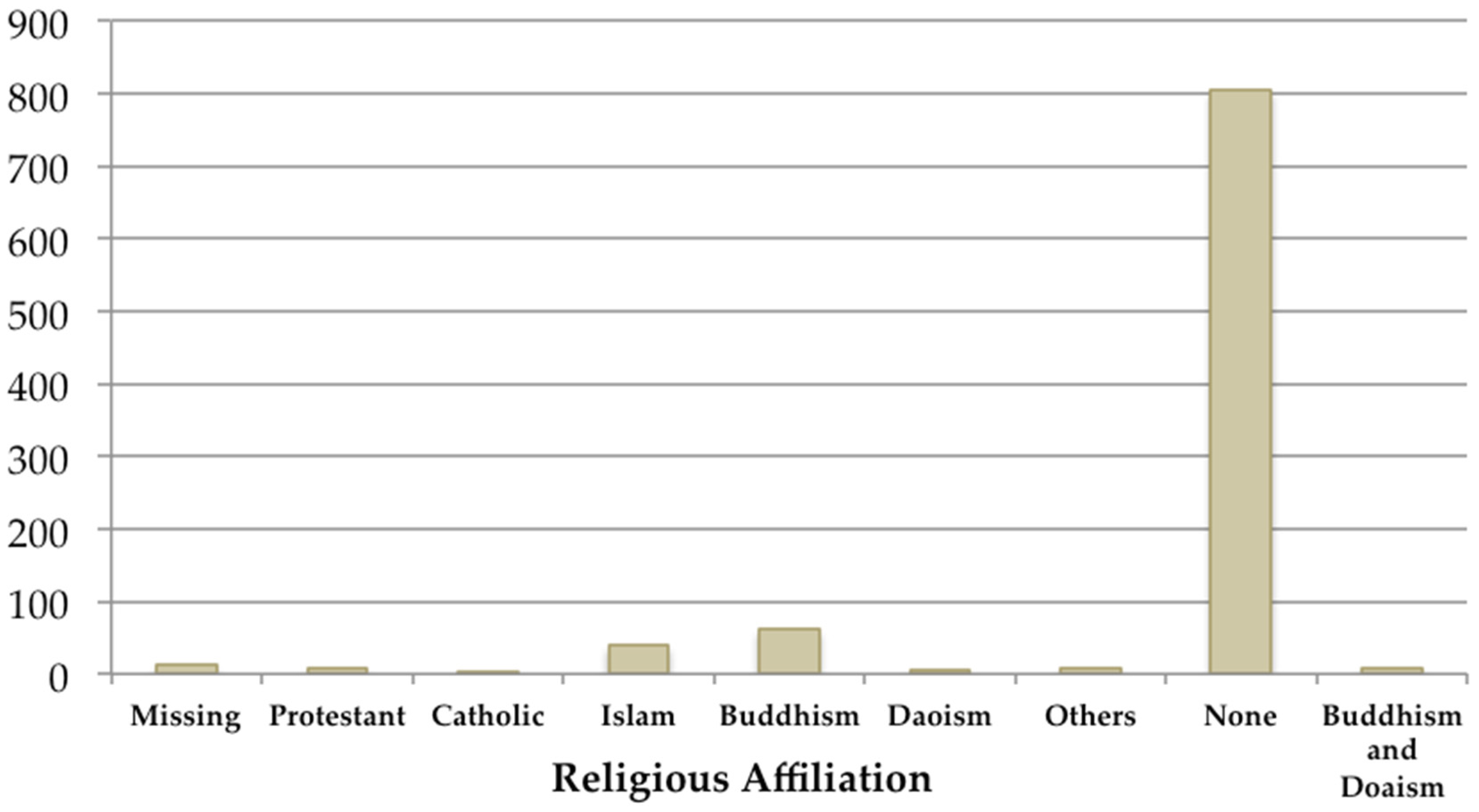

From

Figure 1, it is evident that “No Faith” is the option of the highest number of students, the second is Buddhism, and the third is Islam. Very few responded saying “Christianity”. The proportion of all students who affiliate with a religion is 14 percent, while 86 percent are non-affiliates who responded with “no faith” or no answer. This 14 percent lies in the median range from 3.5 percent to 44 percent.

The difference between the number of affiliates and non-affiliates is quite significant. Among those surveyed, the number of affiliates was 133 out of 950, making up 14 percent, of which 11 were Protestant and Catholics among the 950, accounting for 1.2 percent. The number of non-affiliates was 804, accounting for 84.6 percent; the incomplete questionnaires were 13, accounting for 1.4 percent. The general scenario is that a very small proportion of them are Protestant or Catholic, with most of them subscribing to no religion. The number of students believing in traditional Chinese Buddhism and Daoism together or other religions (including Tibetan Buddhism, Confucianism, and Folk Religion) is 83. There were 39 students who believe in Islam.

The survey produced the following results. Of the college students surveyed in this study, 84.6 percent reported they have no religion; 8.7 percent reported Buddhism, Daoism, Buddhism and Daoism, or Folk religion; 4.1 percent reported Islam; 1.2 percent reported Protestant or Catholic; and 1.4 percent did not respond to this question. These results are the same as the data of the CFPS (Chinese Family Panel Studies) 2012 generated by the Institute of Religion and Culture of Beijing University. Their data showed that only 10 percent of Chinese regard themselves as affiliated with religion. Most respondents (89.6 percent) think they have no religious faith. Buddhism, with numbers almost double those of other religions, is still the most influential religion in China, with 6.75 percent of the interviewees regarding themselves as Buddhist. Furthermore, the CFPS data indicated that 1.9 percent of Chinese are Christians, which equates to approximately 26 million Christians living in China now. This makes Christianity the second largest religion of the Han ethnic group [

6]. The outcomes of two surveys are similar. The reason that Islamic affiliates outnumbered Christians here is that more minority students were interviewed.

However, the Pew Forum’s data indicates that 5 percent of the Chinese population numbers approximately 67 million people. Meanwhile, the CFPS’s survey indicated a 1.9 percent Christian population proportion in China, while our survey indicated a 1.2 percent proportion of Christians among college students. We consider that the Pew results differ based on the use of estimated data. Moreover, both the definition of particular religions and the method of survey used are different in each of the studies. It is possible that, under Communist rule in China, some religious people do not admit their faith, so that the true data is higher than the survey results suggest.

In that survey, the results do not appear to be significantly influenced by the factors of gender, grade, and subject major. However, the ethnic factor is more significantly related to the expression of religious faith, especially for the followers of Islam or Tibet Buddhism. “Most Chinese Muslims belong to one of several ethnic groups that are overwhelmingly Muslim. The 2000 Chinese census included a measure on ethnicity. While not all members of these ethnic groups would necessarily identify as Muslim, the Census figures provide a reasonable and generally accepted approximation of the size of China’s Muslim population” [

7].

Table 1 presents the results of the survey in this study and shows that most of the students do not follow any faith. The Han students’ main faith is Buddhism, Daoism, or both of them together. The minorities’ faith is mainly Islam and Buddhism (including Tibetan Buddhism). The Protestant designation is more popular among the Han than among the minorities. Among the minorities, 59 out of 121 have religious faith, accounting for 48.76 percent, almost half, but among the Han, 85 out of 822 have religious faith, accounting for 10.34 percent. This comes close to the national figures—100 million of the 1.3 billion Chinese. Of course, this includes Han and minority figures; only the Han total 10.34 percent in this survey.

In

Figure 2, a higher ratio of religious identity among ethnic minorities is demonstrated (59 of 121; 48.76 percent). Most in this group believe in Islam, Buddhism, and Tibetan Buddhism. Han and other minorities believe in other religions. Non-affiliation is high. Hardly any of the students identified themselves as Christians. Knowing this, the next question is whether the small number of Christians have made an impact on others in terms of their views about Christianity and about the missionary work associated with some Christians in China.

3.3. College Student Views about Christianity

From among all the students who took the survey, 306 of 901 (34 percent) have respect for the Christian faith, 466 of 901 (51.7 percent) oppose Christian missionaries; only 17 of 901 (1.9 percent) consider it to be a religion of superstitions; and 111 of 901 (12.3 percent) have no idea. From this we realize that most students respect the Christian faith, but do not like missionary activities. Moreover, the superstition response, which was the common view of religion in the past, is equated with religion by few students today. These results are displayed in

Table 2.

Table 3 preliminarily investigates whether there appears to be a difference in attitudes toward Christianity between religious affiliates and non-affiliates. Among the 762 respondents who followed “no religion”, 247 reported “respect”, accounting for 32.41 percent, and 402 respondents, accounting for 52.76 percent, opposed missionary activities. Only 14 people, accounting for 1.84 percent, reported their opinion that Christianity is superstitious. Among those who identified themselves as Protestant or Catholic, almost all of them stated that they respected the Christian identity. Among followers of Islam, Buddhism, Daoism, and other religions, only three people thought Christianity was superstitious. This meant that most students respected the Christian faith, few considered the religion to be superstitious, but most, among both religious affiliates and non-affiliates, opposed missionary activities. This is a general trend in contrast to other variables that include gender, grade, major, and ethnic group. People who believe in a religion and those who do not have different attitudes toward the Christian faith; among the religious affiliates, Christians and non-Christians have different attitudes.

The proportion of students who are respectful and neutral toward those having Christian beliefs was 85.6 percent while those thinking of them as superstitious accounted for only 1.8 percent, and 11.7 percent were indifferent. Overall, this indicated that, although they are not Christians, the vast majority of them adopt an accepting or neutral attitude toward Christianity. This is because the majority of students believe that it is acceptable for college students to have religious beliefs. That is to say, most the college students generally accept the religious affiliates.

Students’ attitudes toward Christianity are more respectful than antagonistic. While most of the students reported not liking missionary activities, they also indicated that young people are generally accepting of religious culture and have great regard for the social role of religion in the contemporary era. That is the reason for their interest in Christianity. However, the acceptance does not necessarily lead to affiliation with the Christian faith and following its beliefs—not publicly at least. Some young people who often attend the activities in a church or a fellowship group do not particularly believe in the Christian message [

8]. Thus, most of these college students do not affiliate with Christianity. But are they interested in learning about it?

3.4. Students’ Interest in Learning about Christianity

As discussed above, most students respect Christianity, but are not personally interested in converting. If they had not been exposed to Christianity, would they have been interested in learning about it?

Table 4 shows that most of these students have no interest in learning about Christianity: 399 out of 950, accounting for 44.3 percent. Only 196 of the 950 answered “yes”, accounting for 21.8 percent. The other 304 out of 950 marked “no idea,” accounting for 33.8 percent.

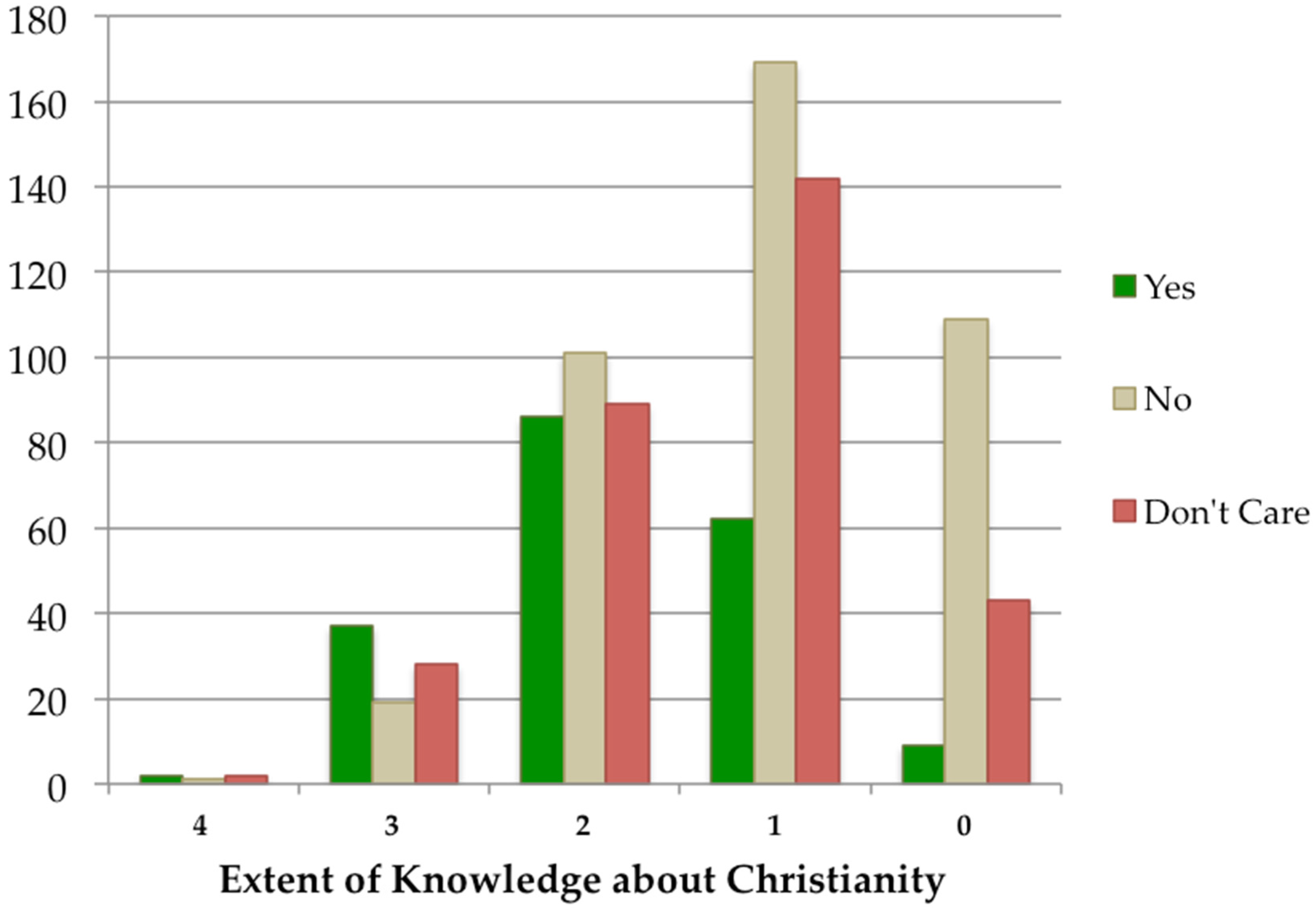

Does knowledge about Christianity relate to interests in learning about it? From

Table 5, we see that, among those with the most understanding, 2 out of 5 are interested, 1 out of 5 are not interested, and among those who had little understanding, 37 out of 84 are interested, and 19 out of 84 are not interested. With an average understanding of Christianity, 86 out of 277 showed interest, 101 out of 277 had no interest. Among those with little understanding, 62 out of 373 showed interest, 169 out of 373 had no interest. Therefore, students who know more about Christianity are more interested in learning about it than students who knew very little about it.

The chart in

Figure 3 reads from left to right, the green bar indicating “interest” and the yellow indicating ”no interest”. The students who have more knowledge of Christianity are interested in learning more about Christianity. Note that the green bar is higher than the yellow bar in column “4” (learn most) and ”3” (learn more).

Comparing the results from different disciplines in

Table 6, we see that students majoring in the Arts (Liberal Arts, Foreign Languages, and Sports) are more numerous in our respondent group than students in the Sciences (Science and Technology and Medicine). Of students in the Arts, 112 of 196 (57.14 percent) are interested in learning about Christianity, whereas, among students in the Sciences, 79 of 196 (40.31 percent) are interested in learning about Christianity. Meanwhile, among the students with “no interest”, this trend is reversed. The Sciences group (220 of 399 respondents, accounting for 55.14 percent) has more students with no interest than the Arts group (165 of 399, accounting for 43.86 percent). Therefore, the discipline in which students are majoring appears to be an important factor that is related to interest in learning about Christianity.

Are different attitudes connected to the interest in learning about Christianity? We see from

Table 7 that the students who respect Christianity are also those interested in learning about it and

vice versa. Overall, college students’ interest in learning about Christianity is related to the extent to which they have an understanding of the faith, their attitude toward Christians, and the discipline in which the students are majoring. The number of students who have an interest, have no interest, or are indifferent is 196 (20.6 percent), 399 (42 percent), and 305 (32.1 percent), respectively. Those who have clearly expressed no interest account for 42 percent (nearly half), and those who are interested are possibly those who only have a superficial interest, showing a low level of participation in Christian activities; their interest is mainly satisfied indirectly from books.

3.5. Students’ Knowledge of Christianity is Related to Communicating with Christian Friends

To investigate correlates of student knowledge of Christianity,

Figure 4 first presents the results of the student knowledge rating. From

Figure 4, it is clear that most students report that they know very little about Christianity; more than half of them (the yellow and purple) know little to nothing. “Just so-so” knowledge of Christianity is represented by the brown khaki section. “Know quite a bit” and “very familiar” are green and blue, respectively.

When students had a connection with religion, their knowledge about Christianity was higher.

Table 8 presents the results of crosstabulations analyzing knowledge of Christianity and whether students have Christian friends and shows greater knowledge among those with Christian friends. Thus, interest and understanding of Christianity are linked, perhaps because interest promotes learning about faith, or perhaps because learning about faith promotes interest. Both possibilities may be true. The causal order is unknown from this cross-sectional analysis, but this preliminary analysis has established that there appears to be a relationship between the two. Next, we investigate possible sources of religious exposure.

Table 9 shows that students who have Christian friends understand Christianity more than those who have no Christian friends. We understand this to mean that having Christian friends is related to students’ knowledge of and interest in learning about Christianity.

Understanding of Christianity may also be related to the degree of participation in religious activities. Among the five students who understand Christianity quite well, three have not participated in Christian activities; 43 out of 85 students who understand Christianity well have not participated in Christian activities; and 202 out of 277 students who have little understanding have not participated in Christian activities. This indicates that their level of understanding is not necessarily linked to their level of participation. Perhaps instead college students’ understanding of Christianity results from textbooks, the Internet, film, and television or from having Christian friends and classmates, without any formal contact with Christianity or Christians. This seems likely since the survey regarding their intent shows that even those students who have participated in Christian activities do not necessarily show a high degree of interest in Christianity. Thus, further investigation is needed into the sources of religious exposure.

3.6. Sources from Which Students Learn about Christianity

College students reporting religious affiliation appear to have learned about Christianity from different sources than non-affiliates. Most affiliates attribute their knowledge about Christianity to their family (47.9 percent), friends (18.8 percent), or from attending religious meetings (10.4 percent). Non-affiliates attribute their knowledge of Christianity to reading religious books (18.8 percent), browsing the Internet (18.8 percent), or being introduced through friends (17.6 percent). This indicates that affiliates obtained their religious knowledge from their surroundings, and nearly half from family members. The non-affiliates attribute their religious knowledge to reading books and browsing the Internet. Both affiliates and non-affiliates rarely attribute it to religious broadcasts, leaflets, or religious organizations [

9].

According to this survey, most students learned about Christianity through social networks and the Internet, books, relatives, friends, and religious classes, among others. In addition, a large proportion of college students have not participated in any Christian activities. Their understanding of Christianity continues to come from the Internet, books, and other external sources, which makes it clear that college students’ contact with Christianity is very limited. This is because the total number of university students believing in Christianity in Xi’an is smaller, and the non-affiliates show no willingness to learn more about Christianity from their Christian classmates and friends, thus preventing the further spread of the Christian faith among students.

Leaflets distributed on campus and through fellowships continue to play an important role in introducing Christianity to college students. A fellowship on the campus may be accepted by young students because it is a relaxing place for socializing without a religious discipline or rules. This could help facilitate being around religious affiliates. The members of a fellowship actively build friendly relationships with students and invite them to take part in activities to learn about Christianity. This is a way for students to learn by communicating directly with Christians.

The activities of Christians are not only in the church but also outside the church. The Christian way of life for college students involves being in the fellowship first, not the church. The house church and the fellowship have become more popular than traditional churches for young people. When we surveyed people in fellowships, house churches, and traditional churches, we found that more youth Christians (including college students) gathered in a fellowship or house church rather than in a traditional church. House churches in Xi’an attended by young people (including college students) can number from fewer than 10 communicants to more than 200. However, few young people attended traditional churches. In addition, when interviewed, the young people indicated that the fellowships and house churches were more attractive for them than were traditional churches.

Table 10 shows that the main ways in which students participate in religious activities is by visiting temples, churches, and mosques, where a majority of the Buddhists and Muslims hold their religious activities. Christians organize and participate in more meetings or classes. Most Christians attend the parties of affiliates or take online learning classes, while Buddhists are more likely to participate in other forms of religious activities demonstrating that spiritual advancement is greater than other organizational expressions.

We see from

Table 11 that almost 25 percent of the students encountered the missionaries between one and three times or more. This shows that fellowships have been communicating with college students frequently. As outlined above, most students do not approve of missionary activities, but some of them are interested in learning about the culture of Christianity. Students are invited to attend fellowships around the campus to experience Christian culture, without having to participate in religious activities. This seems to provide a more comfortable atmosphere for participating in social events with Christians.

Table 12 shows that, while the absolute number of females invited to participate in fellowship activities was greater than the absolute number of men, the gender ratio was nearly equal: women numbered 141 out of 561, accounting for 25.13 percent, and males numbered 92 out of 363, accounting for 25.34 percent.

Thus, it seems from these initial descriptive statistics that there are potentially interesting patterns in knowledge about, understanding of, and exposure to Christianity.

4. Summary of the Survey Results

Most of these college students do not believe in religion

. Christianity is not popular among them in Xi’an. As the Pew report showed, “three-quarters of the religiously unaffiliated (76 percent) also live in the massive and populous Asia-Pacific region. Indeed, the number of religiously unaffiliated people in China alone (about 700 million) is more than twice the total population of the United States” [

7]. Christians comprise 5 percent of the population in China, according to the Pew Forum estimates. At present, most young Christians attend fellowships or house churches, and an increasing number of college students are also interested in experiencing cultural Christianity. However, the proportion of Christians remains low among all students.

In a survey taken in the Guizhou province in recent years, most college students believed in a religion before they went to university or college, nearly 76.92 percent. Moreover, 23.08 percent developed their faith during college; meanwhile, 61.54 percent followed the faith as practiced in their family. In addition, they were influenced by their surroundings more than those who had a strong religious inclination [

10].

The situation was found to be similar in Guizhou, Xi’an, and other cities in China. The proportion of affiliates in religion among Chinese in general is not high, but the actual number has been increasing. Buddhism and Christianity are more acceptable to college students. Some students feel that religion plays a positive role in society. They have a tolerant attitude toward religion [

11].

Most students are interested in religion. Most of them get their religious knowledge, especially Christianity, from books or websites, but they have no contact with any Christians. One of the professors said that, on the one hand, young students had passionate feelings about religion that manifest themselves in such aspects as religious festivals, traveling to religious locations, experiences in temples, and religious cultural searching, religious food, and superstitions; on the other hand, the same students do not understand the scriptures or doctrine. They also had less religious fervor.

Most of the students are not familiar with the religion they believe in. Only 3 percent understand their religious rules and texts well, and 16 percent of them do not even know about their religion [

12]. Therefore, religious beliefs of college students can be of three types: they believe in God but do not belong to an religious organization; they are interested but not strongly committed; they have the culture but are not engaged in the spiritual realms of religion [

1].

Finally, we understand the ways in which they get exposure to religion, specifically Christianity: Some of them receive fliers and frequently receive invitations to join a study circle on campus. The missionary effort is greater than it was in the past; a stronger effort is being made to introduce Christianity to more students.

5. Discussion

Why are there fewer Christians in Xi’an when compared to other religious groups? Why do most college students have no knowledge of religion? Why do they have no interest in learning about Christianity? It is partly the atheistic environment in China that is responsible for most people being disinclined to religious thinking. They also do not make contact with religious people. Especially in Xi’an, an inland city in Northwestern China, people are more traditional than those in coastal cities and thus less receptive to Christianity and thoughts from other religious cultures. This is a common phenomenon in China.

Conversely, religion is nowadays experiencing a revival in China; all religions have spread quickly. As we know, in the past thirty years, after several decades of severe repression, new manifestations of religion have been appearing throughout China. Tens of thousands of temples have been reopened or rebuilt. Millions of people have returned to Buddhism, and, once again, huge numbers of Chinese are pursuing their traditional folk religions and worshipping at their ancestral shrines. Meanwhile, tens of millions of Chinese have embraced Christianity, with thousands more converting every day and more than forty new churches opening every week. [

5] Therefore, some people think that Christianity has spread rapidly in all cities in China.

How can we reconcile these two different phenomena? Some scholars contend that the surveys indicate lower numbers of Christians in China, such as in Xi’an, because individuals do not admit their faith to others under communist rule. Indeed, how many college students are believers? There is no consensus.

Meanwhile, Christianity has spread unevenly in different cities in China. In 1919, at the beginning of the Christian missionary effort, Chinese Christians in seven coastal provinces outnumbered those in other provinces, accounting for 71 percent of the total Christian population. The downstream areas of the Changjiang River are home to approximately 80 percent of all Chinese Christians [

13]. Professor Xing Fuzeng’s view is that, in the 20th century, the spread of Christianity in China was unbalanced, with several provinces witnessing quicker growth and Chinese Christians congregating in 4–5 provinces, not including the Shaanxi Province. The Christians in Shaanxi comprised 0.98 percent of the province’s population in 1997 [

14]. At present, according to data obtained from the local government, the ratio of Christians in the Shaanxi Province or Xi’an City is always lower than in some coastal cities.

In 2015, there were approximately 360,000 Christians in the Shaanxi Province, accounting for 1 percent of the province’s total population of 37,000,000 [

15]. Moreover, there are 83,000 Christians in Xi’an, accounting for 0.95 percent of the city’s total population of 8,700,000 [

16]. The proportion of Christians in Xi’an is lower than in other cities. It is, therefore, reasonable to conclude that the ratio of Christians among college students in Xi’an is also lower than in some other cities.

In addition, young people seldom express their religious fervor as compared to the older people. College students are more interested in the attractions around them and often consider religion to be strange. At the same time, religious faiths have rules while students prefer to live easily and without limitations. In one report (Data of CFPS2012), the author indicates that: In general, few people with college degrees believe in religion; Compared with Christian believers, Buddhists tend to be younger and better educated; In Christian, people over the age of 40 believing in Christianity are more numerous than younger believers, people with a higher level or lower level of education believing in Christianity are more numerous than middle level education believers [

6].

Based on the various surveys or estimates, some people think the proportion of Christians in Xi’an should be higher, other people do not think so, whose opinion correctly represents the current trend? This depends on the quality of the survey. In this survey, the finding that Christianity is followed by a low rate of college students reinforces the results of the CFPS2012 Report. We consider that these results reflect the detailed monitoring of religious activities in China. According to related laws and regulations, religious activities can only be held in special places. In essence, displaying religious beliefs and religious practices is prohibited in public, a law which is applicable to university campuses. To be exposed to a religion, a person must first have a chance encounter with believers. Therefore, the first step to make a cognitive connection to Christianity is important. As Ying Xiong said in his article:

The more mature faith is based on cognition (thoughts). When you think God is believable, you begin to believe…you rely on what you believe in your feeling and spirit, you are convinced and then you are the real follower, moving from your thinking to your activities…therefore, faith is the process from initial belief (often feeling) to being convinced. The people who go through the entire process are the real affiliates.

Members of Christian fellowships on campus have become more active in missionary work; thus, students have become exposed to more fliers and have received more invitations from missionaries. In this way, fellowship members provide more opportunities to college students to learn about Christianity. In contrast to traditional missionaries, the fellowship uses certain initiatives and adapts itself to a young person’s way of thinking. The initiative involves making friends with students, adapting to them by decreasing the emphasis on religious rules, and creating an inviting space for young people to learn about Christianity. For most people who convert to Christianity, it is not the faith or the search for the meaning of life that leads them to convert, but their feeling/thinking that a Christian is a good person and that it is good to be in contact with Christians. Therefore, deeply communicating with a Christian does not begin with the so-called “quest of the spirit” but with real experience [

18], and that is why young people more easily accept this faith model.

6. Limitations

It could alternatively be that people who do believe personally in Christianity are still unlikely to report affiliation due to this being a relatively un-socially desirable status to report. [

5] If this is the case, then their low levels of affiliation reported in this survey may not attempt to examine accurately religious affiliation and participation among Xi’an college students.

It is also worth noting that, as a cross-sectional survey, the causal direction of the relationships reported is unknown. For example, interest in Christianity could promote greater understanding, or vice versa. What is indicated by this survey is that the two are related. This provides initial evidence that investigations of this type can be fruitful.

7. Conclusions

In summary, we have found that, despite reports of high and growing rates of Christianity in China, college students in Xi’an still report relatively low rates. What appears to be changing is the degree of participation in, interest about, and understanding of Christianity through multiple forms of exposure to small groups of Christians on college campuses.