Abstract

This article surveys images depicted on the reverses of papal annual medals in the seventeenth century, beginning in 1605 under Paul V (r. 1605–21) with the first confirmed annual medal, and ending in 1700 at the conclusion of the papacy of Innocent XII (r. 1691–1700), a reign that marked a distinct change in papal politics in advance of the eighteenth century. The article mines a wealth of numismatics images and places it within a narrative of seventeenth-century papal politics. In the ninety-six years under consideration, ten popes issued ninety-four annual medals (sede vacante produced generic annual medals in 1667 and 1691). Annual medals are a unique iteration of papal commemorative medals and they celebrate an important papal achievement from the preceding year. The production of annual medals was an exercise in identity creation, undertaken to advance the image of the pope as an aristocratic prince in three specific roles: as builder, warrior, and impresario. The timeliness of the medals makes them valuable sources to gauge the perceived success of the papacy on an annual basis and to chart the political course plotted by popes through the seventeenth century.

1. Introduction

The images produced in numismatic art constitute an overlooked yet revealing resource, particularly in the examination of papal politics in the seventeenth century. This article, grounded in art-historical evidence and iconographic methodology, considers the images found on papal commemorative medals in the wider discussion of early-modern Catholicism. Among the events celebrated on the reverses of these medals are the completion of new buildings, the coronation of saints, the conclusion of peace treaties, and the proclamation of religious decrees. These examples suggest the wide range of concerns to which the papacy applied itself. Taken as a whole they demonstrate the shifting political landscape of seventeenth-century Rome. At the same time, they a vehicle to promote a self-fashioned identity of popes aristocratic princes in three specific roles: as builders, warriors, and impresarios. This image of the pope would dominate until the end of the century, when sea changes in European politics drastically changed the role of the papacy, at which point popes adopted a more pastoral image.

The production of commemorative medals is a common papal practice, with the tradition probably beginning under Pope Nicholas V Parentucelli (r. 1447–1455), who likely revived the ancient Roman custom. Nathan Whitman ([1], p. 820) contends that the first papal medal was from 1455 and featured a navicella scene on the reverse, see also Reference ([2], p. 63). For ancient propagandistic use of medals see Reference ([3], pp. 66–85). Recipients of these medals included Vatican employees, important visitors to Rome, a “better class of pilgrim”, and visiting dignitaries ([4], p. 69); see also Reference ([5], p. III). Thousands of individual medals were issued by the papacy in the seventeenth century, as well as other European elites, which indicates the widespread production and importance of medals. Subsequent restrikes of medals could continue for years after the original series was issued, inflating the numbers of medals in circulation even more. Medals were widely collected, and their display was a matter of some prestige. John Evelyn, the famous English visitor to seventeenth-century Rome, consistently and repeatedly describes in his diary the medal collections owned by the important people he visited in Italy, and he comments that he continually met “learned men consulting and comparing the reverses of medals and medallions” ([6], p. 692) (note here that he specifies the reverses of medals, suggesting that the reverse images were more significant). Once in Rome, Evelyn vividly describes a visit in February 1656 to the markets in Piazza Navona where medals were regularly sold ([6], p. 137). The collection of commemorative medals in the early modern period has been likened to the collection of important books in a scholar’s library: Collectors were keen to have solid collections, to display them with some pomp, and in general to compete with other collectors ([7], p. 239).

Annual medals are a unique iteration of the papal commemorative medal for more on the typology of papal medals, see Reference ([8], pp. vii–x; [9]). Annual medals were issued on 29 June of each year on the feast of Sts. Peter and Paul, one of the most significant dates on the Roman calendar. The obverses of these medals show portraits of the issuing pope, along with his name and the pontifical year. The reverses, meanwhile, commemorate an important event from the preceding year. Images rarely were repeated on annual medals, and pastoral images almost never appear. Instead, annual medals proclaim official, specific, and timely political messages, and their size, number, and value allowed the deployment of a “portable propaganda” strategy ([10], p. 104). Annual medals were an opportunity to inject papal political messages into the collective worldview of the power elite of early-modern Europe who commonly collected commemorative medals. Papal recognition of the propagandistic potency of annual medals is suggested by two important initiatives on the part of Urban VIII Barberini (r. 1623–44): first, in 1632 the first-ever list of annual medals, recorded as an internal document, was begun and continued by subsequent popes; and second, whereas tradition had allowed for medalists to keep the dies they made and to continue to strike medals, Urban acquired the dies for his medals, and prohibited the dispersal of other papal dies ([4], p. 70); see also Reference [11]. In attempting to maintain possession of the dies, Urban sought to prevent unauthorized restrikes, and thus control the production and distribution of his medals, as well as their messages ([12], p. 220); on limiting restrikes, see Reference ([13], pp. 22–24). Papal production of commemorative medals generally, and annual medals specifically, ramps up after Urban. At the beginning of the century, Paul V produced just over 100 series in sixteen years as pope, while Urban produced over 200 series in twenty-one years; a decade later Alexander VII Chigi (r. 1655–67) would produce almost as many as Urban, but in half the time. Size increased as well, as annual medals went from 30–35 mm in diameter at the start of the century to 40–45 mm [5]. A central purpose of annual medals, therefore, was to release timely political messages to other elite powers enabling the popes to position themselves among the great princes and leading actors on Europe’s political stage.

Though popes always claimed ecclesiastical authority, the image presented in the annual medals is that of the pope as Renaissance prince and successor of the Roman emperors. The Res Gestae Divi Augusti, for example, enumerates Augustus’ achievements, including building projects from temples to aqueducts; the conduct of great wars; and sponsorship spectacles such as triumphs, gladiatorial games, and naumachiae. The Res Gestae was re-introduced in the Renaissance in 1555 by the circle of Augier Ghiselin de Busbecq, though somewhat neglected until the eighteenth century. Still, the conception of successful leadership constructed by the Res Gestae would have been known to seventeenth-century popes through a host of ancient sources, such as Seutonius and Eusebius. Later, the Liber Pontificalis established the close connection between emperors and popes, and reiterated the tenants of good leadership by listing often a pope’s political achievements, architectural projects, and enrichment of the Church. By the early-modern period, popes widely considered Constantine as the “exemplum of the ideal ruler” ([14], p. 195). Constantine’s reign included military and diplomatic triumphs, great building projects, and medals commemorating those achievements. Taken as a whole, the annual medals of the seventeenth century present an analogous image of the popes: they were magnificent builders; they were players in European affairs, specifically in terms of war and peace; and they presided over a city of spectacles.

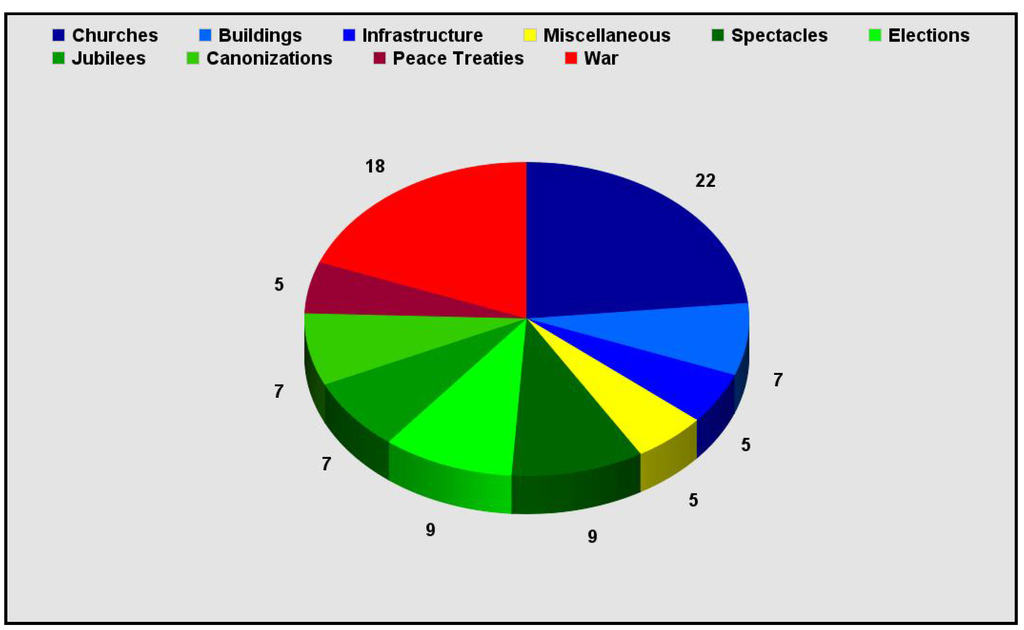

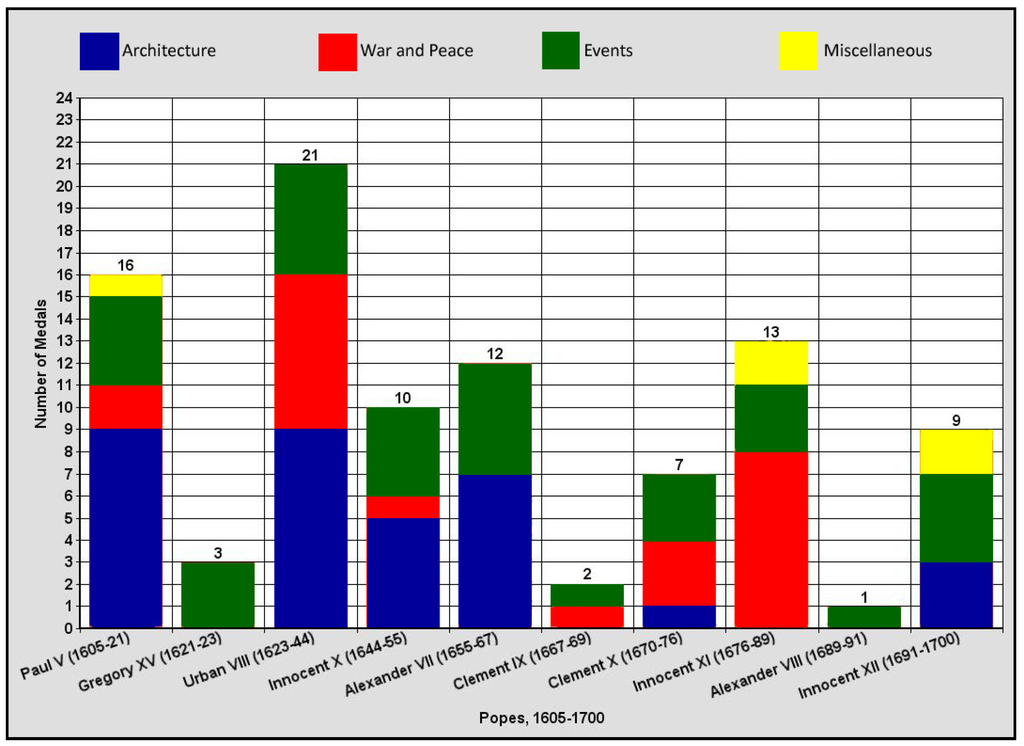

The medals can be divided into three broad groups: architecture, war, and spectacles (see Figure 1 and Figure 2; see also Appendix). For greater specificity, these groups can be subdivided into smaller categories. There is overlap: for example, Urban VIII’s renovations on the Palazzo Quirinale are architectural, but are also military improvements. There are also five annual medals with generic images, which are included in the chart under the heading “Miscellaneous”: This group includes three medals depicting Peter (1607, 1694, and 1698) and two showing female personifications of the Catholic Church (1680 and 1683). Finally, Sede vacante produced two more miscellaneous medals that were not counted in this survey because they lacked a papal patron and thus the political agenda (if any) remains obscure.

Figure 1.

Papal Annual Medals (1605–1700: Distribution by Subject). Credit: Author.

Figure 2.

Papal Annual Medals (1605–1700: Distribution by Pope). Credit: Author.

2. Architecture

Of the ninety-six annual medals issued between 1605 and 1700, 34 depict a wide range of architectural projects. Architecture on medals likely revives an ancient tradition [15]. Architecture is by far the largest category of annual medals, and churches comprise the largest subcategory. Building projects, both magisterial and mundane, contributed to the construction of the image of the popes as munificent rulers, emulating the great builders of imperial Rome. The importance of building for Roman emperors is neatly summarized in Augustus’ supposed boast that he found Rome a city of brick but left it a city of marble, and reinforced in the Res Gestae. Undertaking building projects as an aspect of being a good prince was commonplace by the sixteenth century, and appears, for example, rather matter-of-factly in Baldassare Castiglione’s Il Cortegiano (1528). Castiglione notes Cesare Gonzaga’s contention that the prince ought to “build great edifices both to win honor in his lifetime and to leave the memory of himself to posterity” ([16], p. 320). With the return of the papacy to Rome in 1420, architecture was immediately placed at (or near) the top of the papal agenda. The logic of the papal brand of prestige urbanism was eloquently articulated by Nicholas V (r. 1447–55), who asserted in a deathbed speech (recorded in a biography of the pope by the Italian Humanist Bartolomeo Platina) that:

“Only the learned who have studied the origin and development of the authority of the Roman Church can really understand its greatness. Thus, to create solid and stable convictions in the minds of the uncultured masses, there must be something that appeals to the eye; a popular faith sustained only on doctrines will never be anything but feeble and vacillating. But if the authority of the Holy See were visibly displayed in majestic buildings, imperishable memorials and witnesses seemingly planted by the hand of God himself, belief would grow and strengthen from one generation to another, and all the world would accept and revere it. Noble edifices combining taste and beauty with imposing proportions would immensely conduce to the exaltation of the chair of St Peter.”(Quoted from ([17], p. 16)

Building “noble edifices” was but one arm of the papal architectural pincer; the other was to rebuild Rome’s infrastructure, which had fallen into a great state of disrepair. As Platina also describes:

“…Rome [was] in such a state of devastation that it could hardly be considered a city fit for human habitation: whole rows of houses abandoned by their tenants; many churches fallen to the ground; streets deserted and buried under heaps of refuse; traces of plague and famine everywhere.”(Quoted from ([18], p. 10)

Early-modern popes thus resolved to remake Rome into a new papal Caput Mundi, and they achieved this goal by engaging in both utilitarian and ecclesiastical architectural projects. These projects included among other things streets, bridges, harbors, fountains, aqueducts, military fortifications, city walls, orphanages, hospitals, and granaries. Annual medals demonstrate this great diversity, and the medals of Paul V are a particularly revealing set. Eleven of his sixteen medals commemorate architectural projects, five of which were utilitarian: the Aqua Paolo (1609), a fortress in Ferrara (1610), an expansion of the Palazzo Quirinale (1616), the Porta Vaticana (1618), and a bridge in Ceprano over the Liri River (1620). The inclusion of utilitarian projects on annual medals indicates that the popes recognized that such projects were fundamental elements of good governance.

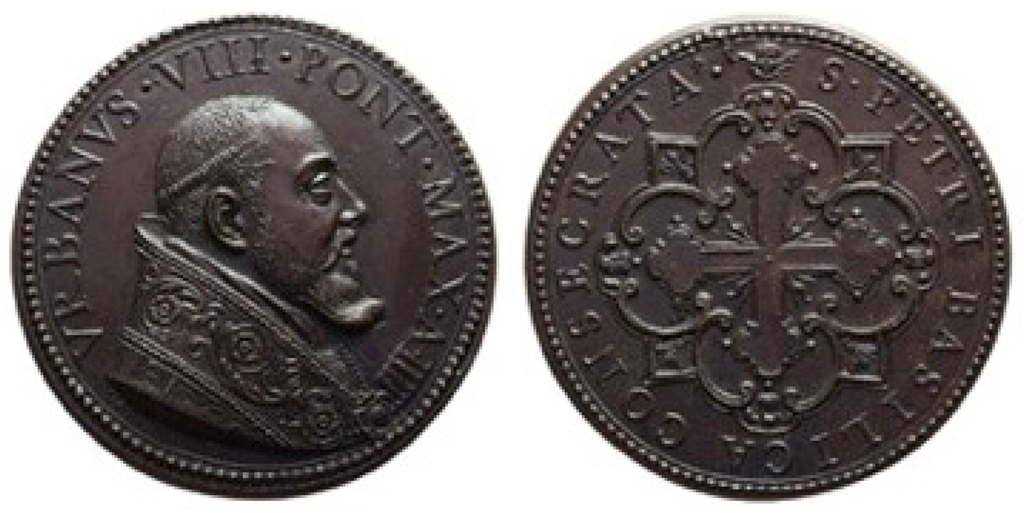

Churches were essential projects, as well, and six of Paul’s annual medals commemorate work he undertook on ecclesiastical structures, including the venerable Santa Maria Maggiore (depicted on annual medals in 1606, 1612, and 1616). Though there were many new churches built in early-modern Rome, the popes often focused on ancient churches, as these were manifestations of Catholicism’s long pedigree stretching back to the Roman emperors. These buildings were material demonstrations of papal summa potestas. St. Peter’s was the most important of all of the churches in Rome as it was simultaneously a symbol of the ancient imperial Church of Constantine, while also a beacon of the resurgent post-Tridentine Catholic Church. Even before Trent, St. Peter’s was the focus of papal resistance to potential rival civic authorities in Rome, as well as conciliar and schismatic movements elsewhere in Europe ([19], p. 64). St. Peter’s became a physical embodiment of the long-standing concepts of the eternalness of Rome and the primacy of Peter ([20], p. 11). The centrality of St. Peter’s is reflected in the annual medals: at least fifteen of them depict the basilica’s construction and ornamentation. Paul V commemorated the completion of the façade of St. Peter’s with the annual medal of 1613 and the Chapel of the Confession in St. Peter’s with the annual medal of 1617. Urban VIII issued two annual medals in 1627 to commemorate the (re)-consecration (and therefore completion) of St. Peter’s in the previous year, the supposed 1300th anniversary of the church’s original consecration (Figure 3). Later, Alexander VII issued three consecutive annual medals that celebrated work at St. Peter’s: Bernini’s colonnade (1661), the Cathedra Petri (1662), and the Scala Regia (1663).

Figure 3.

Gaspare Mola, Consecration of St. Peter’s (Urban VIII Annual Medal 4), 1627. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Alexander VII was a builder and his reign was a period of major construction programs. The grounds for his well-earned sobriquet “Papa di grande edificazio” can be seen in his annual medals: seven of his twelve commemorate building projects. By the end of Alexander’s reign in 1667, the grand vision of Rome imagined by Nicholas V two centuries earlier had been realized through the combined efforts of over thirty popes, and Alexander’s additions were the crowning achievements ([21], p. 85); see also References [22,23]. Yet his building campaigns contributed in no small part to the dire financial straits in which the papacy found itself at the end of Alexander’s reign ([24], pp. 171–72). After Alexander, major architectural expenditures diminished to a trickle as the papacy flirted with bankruptcy and new priorities emerged in the 1670s, particularly the perceived threat of a Turkish invasion ([25], p. 291).

3. War

In addition to the image of the pope as a builder, there is also the image of the pope as a warrior, and this militant image was promoted on twenty-three annual medals in the seventeenth century. Such images include those that commemorate the construction of military fortifications, the establishment of the Vatican Armory, and the celebration of papal-led military victories. A militant papacy was legitimized at least as early as the fourteenth century by Boniface VIII (r. 1294–1303), who in 1302 issued the bull, Unam Sanctam. The bull professed the doctrine of papal primacy asserted through the wielding of spiritual and material swords, “the latter by the hands of kings and soldiers, but at the will and sufferance of the priest.” The bull concludes that “it is absolutely necessary for salvation that every human creature be subject to the Roman Pontiff” (for the origins of Unam Sanctam, see [26]). Paul II (r. 1464–71) displayed the twin swords on his coat of arms, a unique case in papal heraldry. Later, Giles of Viterbo, preaching before Julius II (r. 1503–13) in 1507 advanced the case for the temporal authority of the popes, arguing that “Christ is head of heaven, Rome head of earth; Rome sovereign, Christ sovereign” ([27], p. 192). Nine years after that, in 1516, Leo X (r. 1513–21) reissued the Unam Sanctam.

At the dawn of the seventeenth century, the Jesuit priest Juan Mariana revived these ideas in the controversial De rege et regis institutione of 1598, and this conception of papal power remained valid through the seventeenth century ([28], vol. 29, p. 360). Urban VIII, for example, undertook a vast rearmament program purportedly to secure the Papal States from foreign domination ([29], pp. 41–78; [28], vol. 29, pp. 360–66). As Andrea Nicoletti argued in his Life of Pope Urban VIII:

“In this armament [Urban] had no other plan than to secure beforehand the Apostolic See for the defense of Rome and the Ecclesiastical State without it being necessitated that there be mediations by foreign princes, which some earlier Pontiffs, reduced to a calamitous state, were constrained to beg for from others.”[30]

Urban’s annual medals often convey a martial image: seven of his twenty-one medals are expressly about war, and at least five more deal with war obliquely ([31], p. 304). Urban’s militarism was in keeping with European state-building in the early-modern period and contributed to a princely identity that would have found resonance with other power elites ([32], pp. 191–95). Both Machiavelli and Castiglione describe a truculent prince: Machiavelli largely in Book XIV of The Prince, and Castiglione in various places throughout Il Cortegiano. Notably, in the latter text, Castiglione has signor Ottaviano Fregoso ask,

“…what more noble, glorious, and profitable undertaking could there be than for Christians to direct their efforts to subjugating the infidels? Does it not seem to you that such a war, if it should meet with good success and were the means of turning many thousands of men from the false sect of Mohammed to the light of Christian truth, would be as profitable to the vanquished as to the victors?”([16], pp. 321–22)

The pope as crusader who makes war on the Muslims was all the more prominent after the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, which was characterized as Christendom’s greatest victory as it opened the way to Jerusalem (via Constantinople) and the restoration of the Christian world originally established by Constantine ([33], pp. 76–77). Popes of the seventeenth century were keen to initiate crusades against the Ottomans. Urban VIII, for example, admired Urban II (r. 1088–99) who called for the First Crusade. The latter Urban hailed his namesake as a “great unifier of all Christianity against the Turkish conquest of the Holy Land” ([29], p. 11). Urban VIII continued calls for holy war against the Ottoman Empire through his poetry from 1633/34 ([34], p. 106).

European powers and the Ottoman Empire continued to war throughout the seventeenth century, and this ongoing conflict produced medals with some of the most militant messages of the seventeenth century. Under Innocent XI (r. 1676–89), eight of thirteen annual medals dealt with military matters. Innocent’s reign fell within a span of twenty-one years in which thirteen medals were dedicated to war. This corresponds to the papacy’s escalating prosecution of the Great Turkish War, a conflict between European superpowers and the Ottoman Empire that occurred broadly between 1681 and 1700 ([35], pp. 286–327). Innocent initiated a new Holy League in 1684, and commemorated this achievement in that year’s annual medal (Figure 4). The reverse shows the members of the new League represented by crowns arrayed on an altar: from left to right, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, the Papal States under Innocent XI, Polish King John III Sobieski, and Venetian Doge Marc Antonio Giustiniani.

Figure 4.

Giovanni Hamerani, Alliance of the Holy League against the Ottomans (Innocent XI Annual Medal 8), 1684. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Although Innocent XI’s successor, Alexander VIII (r. 1689–91), issued but a single annual medal (commemorating his election), he did strike several other medals concerning the war with the Ottomans. And militant images turn up in other places: Alexander canonized five men on the same day in 1690, three of whom were warriors, John of Capistrano, John of God, and Lorenzo Giustiniani. Lorenzo (who in addition to being an ancestor of the aforementioned and then-current Doge of Venice, Marc Antonio Giustiniani) was Patriarch of Venice when Constantinople fell to the Ottomans in 1453, a devastating event that current European powers were seeking to reverse. Like Alexander VIII, Urban VIII combined war and canonization: the 1629 annual medal commemorates the canonization of Andrea Corsini, a fourteenth-century Florentine saint. The medal presents Urban reciting the canonization chant, which enrolls Andrea in the catalog of saints. The medal reinforces the Council of Trent’s emphasis on the veneration of saints. Corsini, however, also had military associations, as he purportedly appeared at the Battle of Anghiari in 1440. This important Florentine victory over Milan (celebrated in the Palazzo Vecchio in a now-lost fresco by Leonardo da Vinci) was a cornerstone of Florentine military lore, and surely factored into Urban’s decision to depict the spectacle of Corsini’s canonization on the annual medal.

4. Spectacles

Rome was a city of spectacles and they appear on thirty-one annual medals in the seventeenth century. Pageantry was fundamental to the cultural life of the city ([27], p. 51). Grand processions wound through the city for important events, notably the possesso, the culminating event in the coronation of a new pope ([36], p. 43). Confraternities and pilgrims regularly paraded through the city ([37], p. 116). Processions followed by performances could welcome new monuments, such as the festivities for the unveiling of the Four Rivers Fountain in Piazza Navona in 1651 (For a contemporary account of the unveiling, see Reference [38]; see also Reference [39], p. 147). Piazze were regularly converted into festival spaces for jousts, naumachiae, and the like [40]. Fireworks often lit the Roman night on important holidays, especially the Feast of Sts. Peter and Paul and throughout Carnivale, as well as during visits of important dignitaries ([41], p. 17). The frequency and prominence of spectacles can be seen in the annual medals, with a third of them depicting events such as papal processions, canonizations, and Jubilees.

The veneration of saints was often the impetus for spectacles in Rome. The Council of Trent explicitly commanded that the faithful give “due honor” to saints ([42], p. 215). In Rome this produced a frenzy of activities focused on the canonized, from excavations for ancient holy bones to the construction of new churches. This emphasis on saints is demonstrated in the annual medals as well: some document religious processions, others depict new architecture dedicated to saints, and still others record canonizations. Paul V’s annual medal from 1615 commemorates a lavish procession for the burial of the bones of St. Agnese and St. Emerenziana, whose remains had been recently discovered during restoration work on the Church of Sant’ Agnese fuori le Mura ([8], p. 615). Popes promoted their dedication to saints by constructing new churches or refurbishing old ones, and recording their efforts on annual medals, as Urban VIII did with a trio of annual medals showing the churches of San Caio (1634), Santa Bibiana (1635), and Sant’ Anastasia (1636). The most important act of veneration, however, was canonization itself. The Council of Trent unleashed a wave of canonizations that rolled through the seventeenth century, and they were accompanied by great public spectacles consisting of lavish processions that terminated at St. Peter’s wherein, during a venerable ceremony, holy personages were enrolled in the catalog of saints amidst ephemeral architecture ([43], p. 244). Through the seventeenth century, six annual medals commemorate the canonization of fourteen new saints. Notable among this group of medals is Gregory XV’s (r. 1621–23) annual medal of 1622 that records the canonization of Francis Xavier, Ignatius of Loyola, Filippo Neri, Teresa of Ávila, and Isidore the Laborer.

In addition to frequent canonizations and religious processions there were Jubilees. Proclaimed generally every twenty-five years, Jubilees were important events for the papacy and for Rome. Jubilees showcased the grandeur of papal Rome and transformed the city into a physical manifestation of the correctness of the papacy’s policies, the demonstration of which was all the more important after the Protestant Reformation (Protestant Jubilees, for example, were held throughout Germany in 1617, the Centennial of Martin Luther’s Theses, as a counter-point to Catholicism). In the period under review, there were four Jubilees, which produced seven annual medals. These medals depicted Jubilee ceremonies at St. Peter’s, reinforcing Irving Lavin’s observation that the new basilica was shaped in the seventeenth century into a site for “performance and involvement of the faithful” ([44], p. 7). Five of the seven Jubilees depict events involving the Porta Santa. The Porta Santa, the northernmost of the trio of doors inside the narthex of St. Peter’s, is normally sealed with a brick wall. In a ceremony on Christmas Day, the first day of the Holy Year, the pope strikes the wall with a silver hammer, symbolically opening the door and beginning the Jubilee. With the door opened, pilgrims could pass through it, earning a plenary indulgence. Medals from Jubilee years typically depict this ceremony. Urban VIII’s annual medal from 1626, however, is unique in depicting the closing of the Porta Santa (the closing of the Porta Santa is commonly often depicted on commemorative medals, though Urban is the only pontiff to celebrate it on an annual medal). The medal shows a congregation of bishops with Urban at the center, placing the first of the bricks used to reseal the door. Placing a brick to close the Porta Santa suggested the reconstruction of the Basilica, and further linked Urban to Constantine who, according to the Acta Silvestri, carried stones on his back to construct Old St. Peter’s ([14], p. 200); on Constantine’s questionable involvement with the construction of St. Peter’s, see Reference [45].

Secular spectacles abounded as well. Perhaps the greatest cultural event in seventeenth-century Rome was the arrival of Queen Christina of Sweden in 1655, an event fêted as a triumph for the Catholic Church. Alexander VII commemorated the event on the annual medal in 1656 (Figure 5). For reasons both political and religious, Christina abdicated her throne on 30 May 1654 ([46], p. 719). Thereafter, she departed Sweden on a tour of important northern cities, arriving in Brussels in time to secretly convert to Catholicism in a ceremony on Christmas Eve 1654. Later the next year she set out for Italy, pausing in Innsbruck where she publically re-enacted her conversion in the Hofkirche, after which she descended into Italy accompanied by papal ambassadors. Though Christina actually arrived in Rome via the Vatican very late on 20 December, her official entry into Rome was postponed until 23 December and moved to the Porta del Popolo. Her entry through that gate was a staged event designed to maximize its propagandistic effect. The inner façade of the Porta del Popolo, which Bernini had recently built, still bears the inscription (written by Alexander himself) FELICI FAVSTOQ INGRESSVI ANNO DOM MDCLV (For a happy and propitious entry, in the year of our Lord 1655). A truncated version of this inscription also appears on the annual medal. The Piazza del Popolo was decorated for Christina’s arrival and Bernini’s new gate converted the piazza into a performative space in which Christina’s arrival became another act in the long drama of Catholic–Protestant antagonism ([47], pp. 54–55). Alexander declared a public holiday for the city, and the seventeenth-century Roman diarist Giacinto Gigli noted that in honor of Christina’s arrival all the shops should be kept closed and “the streets through which the Queen passed, from Porta del Popolo to St. Peter, should be ornamented” ([48], p. 752).

Figure 5.

Gaspare Morone, The Arrival of Queen Christina of Sweden in Rome at the Porta del Popolo (Alexander VII Annual Medal 2), 1656. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

5. Fin-de-Siècle

Christina’s residence in the city was a highlight of Baroque Rome. By the advent of the eighteenth century, twilight had come to Papal Rome. Papal military initiatives essentially ceased after Russia joined the Holy League in 1686 and the Romanov czars took the lead in the campaign against the Ottomans. The major building campaigns of early-modern Rome came to a halt after Alexander VII as the papal coffers were exhausted. And while Rome remained a city of spectacles, its pageantry was surpassed by the splendors of Versailles and other European capitals.

Under Innocent XII, the papacy shifted its focus to internal reform and the city of Rome. Innocent was a compromise candidate elected pope in July 1691, ending a protracted conclave that had begun the previous February. Already by the time of Innocent’s election, the papacy had waned in international authority, largely due to the ascendancy of Louis XIV of France. Indeed, it was likely France’s notion that Innocent would be a “weak” pope that finally broke the deadlock in conclave ([49], vol. 2, p. 425). Diplomatically, Innocent exerted little influence in Europe or Italy ([28], vol. 32, p. 579). In Rome, however, Innocent undertook several important reforms, including the abolition of the papal nephew with the 1692 papal bull Romanum decet pontificem. Thereafter, he proclaimed “i miei nipoti sono i poveri” and undertook a massive overhaul of papal charitable policy that included the conversion of part of the Lateran Palace into a hospice for the invalid poor. The annual medal from the next year depicts Innocent XII receiving the poor of Rome, commemorating Innocent’s vast charitable initiatives.

Charitable programs were essential to the construction of modern states ([50], p. 181). The papal social safety net in early-modern Rome developed from two main causes: the first was post-Tridentine evangelism, which sought, as a part of its confrontation with Protestantism, to save souls ([51], p. 181). The other major cause was the rise of European absolutism and modern state formation, or in the case of Rome, the papal consolidation of temporal and spiritual authority. For the papacy, charitable programs fused citizenship with belief and drew people into the authority of the pope, thereby consolidating papal power. To be effective, programs had to be generous and well-organized. Yet, papal investigations of the charitable activities of philanthropic individuals, religious orders, and confraternities too often found them inefficient. Thus, increasingly private initiatives came under the supervision or outright control of the papal government ([50], p. 182). As a result, the papacy, rejected subsidiarity, and largely assumed responsibility for the huge apparatus designed to care for Rome’s poor. Running such a machine required the abilities of an administrator, not a cavaliere.

By 1700, the Renaissance prince was an anachronism. The rise of powerful prime ministers in France and Spain earlier in the century demonstrates that the affairs of state were too large for the kind of ruler modeled on Lorenzo de’ Medici or Guidobaldo di Montefeltro. The pope as sovereign of “every human creature,” as imagined by Boniface VIII’s Unam Sanctam, was clearly an impossibility. Even the more moderate Renaissance dream of the pope as padre commune was not to be ([52], p. 65). There could not even be a Magna Italia, which seemed so tantalizingly close at the start of the century ([53], p. 440).

Though space does not permit a full examination here, some mention should be made of the content of the annual medals after Innocent XII. The next quarter century finds that many of the same categories of medals continue. Twenty-four annual medals were issued by the end of Innocent XIII’s reign in 1724; of these 11 dealt with architecture, five medals with war and peace, and three with spectacles. Though these categories persist, the medals are different in tone. None of the medals commemorate large-scale architectural projects. While five deal with war and peace, only one actually comments on war while the others are calls for peace. This change in perspective on martial medals reflects the papacy’s diminishing role in military conflicts, particularly Rome’s relative lack of participation in the War of Spanish Succession (1701–14). Spectacles alone seem to continue in the same vein, recording a quadruple canonization (1712), celebrating a papal election (1721), and announcing the forthcoming Jubilee of 1725 (1724). What unites these medals (and separates them from their predecessors), however, is their focus on the papacy as a pastoral institution, rather than on the pope as a prince. These medals commemorate a procession for peace (1711), missionary activities (1702 and 1719), and Europe’s first institution for juvenile offenders (1704). While establishing a prison might not seem particularly pastoral, the establishment of the Hospital of San Michele for Juvenile Offenders was a major step forward as youthful offenders were normally sent to adult prisons, often unfairly and often with disastrous consequences. San Michele marks a recognition of, and compassion for, early-modern children, and introduced a number of reforms including providing instruction to reform youths ([54], p. 6). As for the production of medals generally, the numbers of series produced by popes by Innocent XII and afterwards is about half of what they were under Urban [55]. In all, the emergence of annual medals with pastoral messages indicates that while popes continued to present themselves as earthly monarchs, they realized that their role in the drama of European politics had changed.

The medals of the eighteenth century reflect the new identity the papacy tried to fashion for itself. This development was the result of the new pastoral course initially charted for the papacy by Innocent XII, a man acclaimed as ”utterly unselfish”, ”of irreproachable morals”, and whose “one thought [was] serving the Church and the poor” ([28], vol. 32, pp. 577–78). Innocent’s new course can be seen in his annual medals in which the image of a pastoral pope replaces the Renaissance prince: six of Innocent’s nine annual medals have to do with his reforms. This was a watershed moment in the history of the papacy, and Innocent emerges as a transitional figure, linked more to St. Peter than to Augustus. The annual medal of 1694, which shows St. Peter watching over Rome (Figure 6), symbolically suggests the transition from prince to pastor. Innocent’s reforms confirm the papacy’s abandonment of the large building programs, military campaigns, and extravagant pageantry celebrated on papal annual medals of the seventeenth century.

Figure 6.

Giovanni Hamerani, St. Peter Watches Over Rome (Innocent XII Annual Medal 3), 1694. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Acknowledgments

My great thanks to Arne Flaten, Charles Rosenberg, and John Connally, who organized a session on papal medals at the 2014 Renaissance Society of America Meetings in which this paper originated. Thanks also to the editors of Religions and my anonymous reviewers. All errors are my own. I have received funding from my university for both research and to publish this in open access.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix

For identification of Annual Medals, see [5,8,11,13,55,56].

| Year | Subject | Category |

| Paul V Borghese (1605–21) | ||

| 1605 | Election (Dove of the Holy Spirit) | Event |

| 1606 | Construction at Santa Maria Maggiore | Architecture |

| 1607 | St. Peter, Prince of the Apostles | Miscellaneous |

| 1608 | Canonization of St. Francesca Romana | Event |

| 1609 | The Acqua Paolo | Architecture |

| 1610 | Fortezza di Ferrara | Architecture |

| 1611 | Canonization of San Carlo Borromeo | Event |

| 1612 | Completion of Santa Maria Maggiore | Architecture |

| 1613 | Façade of St. Peter’s | Architecture |

| 1614 | Statue of the Virgin at Santa Maria Maggiore | Architecture |

| 1615 | Burial of the Bones of St. Agnese and S. Emerenziana | Event |

| 1616 | Expansion of the Palazzo Quirinale | Architecture |

| 1617 | The Chapel of the Confessione in St. Peter’s | Architecture |

| 1618 | Reconstruction of the Porta Vaticana | Architecture |

| 1619 | La Capella Paolina al Quirinale | Architecture |

| 1620 | Il Ponte di Ceprano sul Fiumi Liri | Architecture |

| Gregory XV Ludovisi (1621–23) | ||

| 1621 | Election (Madonna and Child) | Event |

| 1622 | Canonization of Five Saints | Event |

| 1623 | Papal Mediation between France and Spain | War |

| Urban VIII Barberini (1623–1644) | ||

| 1624 | Election to the Pontificate | Event |

| 1625 | Opening of the Porta Santa | Event |

| 1626 | Closing of the Porta Santa in 1625 | Event |

| 1627 | Consecration of St. Peters (2 versions) | Architecture |

| 1628 | Fortifications at Castel Sant’Angelo | War |

| 1629 | Canonization of Andrea Corsini | Event |

| 1630 | Forte Urbano in Castelfranco Emilia | War |

| 1631 | Devolution of the Duchy of Urbino | Event |

| 1632 | Harbor at Cittavecchia | War |

| 1633 | The Baldacchino | Architecture |

| 1634 | Church of Santa Bibiana | Architecture |

| 1635 | Church of San Caio | Architecture |

| 1636 | Church of Santa Anastasia | Architecture |

| 1637 | Lateran Baptistery | Architecture |

| 1638 | Castel Gandolfo | Architecture |

| 1639 | Vatican Armory | War |

| 1640 | Fortifications at the Palazzo del Quirinale | War |

| 1641 | Ironworks at Monteleone | Architecture |

| 1642 | Barberini Granary | Architecture |

| 1643 | Janiculum Walls | War |

| 1644 | Allegory of the War of Castro | War |

| Innocent X Pamphilij (1644–55) | ||

| 1645 | Election (Angles with Cross) | Event |

| 1646 | Palazzo Capitolino | Architecture |

| 1647 | Decoration of San Giovanni in Laterano | Architecture |

| 1648 | Decoration of St. Peter’s | Architecture |

| 1649 | Announcement of the Holy Year | Event |

| 1650 | Opening of the Porta Santa | Event |

| 1651 | Peace of Westphalia | War |

| 1652 | Four Rivers Fountain | Architecture |

| 1653 | Condemnation of the Jansenism Heresy | Event |

| 1654 | Church of Sant’ Agnese in Agone | Architecture |

| Alexander VII Chigi (1655–1667) | ||

| 1655 | Election to the Pontificate | Event |

| 1656 | Arrival of Queen Christina of Sweden in Rome | Event |

| 1657 | The Plague in Rome | Event |

| 1658 | Church of Santa Maria della Pace | Architecture |

| 1559 | Church of San Tommaso di Villanova | Architecture |

| 1660 | Church of S. Ivo alla Sapienza | Architecture |

| 1661 | The Colonnade of St. Peter’s | Architecture |

| 1662 | The Cathedra Petri | Architecture |

| 1663 | The Scala Regia | Architecture |

| 1664 | Procession of the Corpus Domine | Event |

| 1665 | Canonization of St. Francis de Sales | Event |

| 1666 | Ospedale di Santo Spirito | Architecture |

| Sede Vacante (22 May – 20 June) | ||

| 1667 | St. Peter as Protector of Rome | Not Counted |

| Clement IX Rospigliosi (1667–1669) | ||

| 1668 | The Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle | War |

| 1669 | Canonizations of Two Saints | Event |

| Clement X Altieri (1670–1676) | ||

| 1670 | Election (Roma Resrugens) | Event |

| 1671 | Canonization of 5 Saints (2 versions) | Event |

| 1672 | Tribune of the Basilica Liberiana | Architecture |

| 1673 | Victory over the Turkish Army in Poland | War |

| 1674 | Delivery to Pope of the Captured Turkish Standard | War |

| 1675 | Opening of the Porta Santa | Event |

| 1676 | Fortifications at Cittavecchia | War |

| Innocent XI Odescalchi (1676–1689) | ||

| 1677 | Election to the Pontificate | Event |

| 1678 | Mediation Attempt to Achieve Peace in Europe | War |

| 1679 | The Peace of Nijmegen | War |

| 1680 | The Church of Rome | Miscellaneous |

| 1681 | The War Against the Turks | War |

| 1682 | The Quietism Heresy | Event |

| 1683 | The Church of Rome | Miscellaneous |

| 1684 | Alliance Against the Turks | War |

| 1685 | Occupation of Santa Maura (Lefkada, Greece) | War |

| 1686 | Charity of the Pope | Event |

| 1687 | Victory of the Holy League in Hungary | War |

| 1688 | Victory of the Holy League | War |

| 1689 | Invitation to Persevere in the Fight against the Turks | War |

| Alexander VIII Ottoboni (1689–1691) | ||

| 1690 | Election to the Pontificate | Event |

| Sede Vacante (1 February–12 July) | ||

| 1691 | Peter and Paul on obverse, Holy Spirit on reverse | Not Counted |

| Innocent XII Pignatelli (1691–1700) | ||

| 1692 | Keynote Address of Innocent XII | Event |

| 1693 | Receiving the Poor | Event |

| 1694 | St. Peter Watches over Rome | Miscellaneous |

| 1695 | Palazzo della Curia Innocenziana | Architecture |

| 1696 | Customs House at the Piazza di Pietra | Architecture |

| 1697 | New Impetus for the Collegio di Propaganda Fide | Architecture |

| 1698 | The Apostles Peter and Paul | Miscellaneous |

| 1699 | Announcement of the Jubilee of 1700 | Event |

| 1700 | Celebration of the Jubilee | Event |

References

- Nathan T. Whitman. “The first papal medal: Sources and meaning.” The Burlington Magazine 133 (1991): 820–24. [Google Scholar]

- Georg Habich. Die Medaillen der Italienischen Renaissance. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew Burnett. Coinage in the Roman World. London: Seaby, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- John Varriano. “The architecture of papal medals.” In Projects and Monuments in the Period of the Roman Baroque. Edited by Hellmut Hager and Susan Scott Munshower. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1984, pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Walter Miselli. Il Papato dal 1605 al 1669 Attraverso le Medaglie. Pavia: Numismatica Varesi, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- John Evelyn. Memoirs of John Evelyn, Esq., F.R.S Comprising His Diary, from 1641 to 1705–6, and a Selection of His Familiar Letters. London: F. Warne, 1871. [Google Scholar]

- Luke Syson. “Holes and Loops: The Display and Collection of Medals in Renaissance Italy.” Journal of Design History 15 (2002): 229–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco Bartolotti. La Medaglia Annuale dei romani Pontefici da Paolo V a Paolo VI, 1605–1967. Rimini: Stabilimento grafico Cosmi, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Giacomo C. Bascapè. “Introduzione alla medaglistica Papale.” Rivista Italiana di Numismatica e Scienze Affini 15 (1967): 169–82. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony Colantuono. Guido Reni’s Abduction of Helen: The Politics and Rhetoric of Painting in Seventeenth-Century Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lucia Simonato. Impronta di Sua Santità: Urbano VIII e le Medaglie. Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- John Varriano. “Some Documentary Evidence on the Restriking of Early Papal Medals.” Museum Notes 26 (1981): 215–23. [Google Scholar]

- Adolfo Modesti. La Medaglia “Annual” dei Romani Pontefici. Roma: Accademia Italiana di Studi Numismatici, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tod Marder. Bernini’s Scala Regia at the Vatican Palace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan T. Elkins. Monuments in Miniature: Architecture on Roman Coinage (Numismatic Studies 29). New York: American Numismatic Society, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Baldassare Castiglione. The Book of the Courtier. Translated by Charles S. Singleton. New York: Doubleday, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Peter Partner. Renaissance Rome, 1500–1559. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Rodolfo Amedeo Lanciani. The Golden Days of the Renaissance in Rome, from the Pontificate of Julius II to That of Paul III. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Christof Thoenes. “Renaissance St. Peter’s.” In St. Peter’s in the Vatican. Edited by William Tronzo. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 64–92. [Google Scholar]

- Marie Tanner. Jerusalem on the Hill. Rome and the Vision of Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Renaissance. London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dorothy Metzger Habel. “When all of Rome was Under Construction”: The Building Process in Baroque Rome. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dorothy Metzger Habel. The Urban Development of Rome in the Age of Alexander VII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Krautheimer. Roma Alessandrina: The Remapping of Rome under Alexander VII, 1655–1667. Poughkeepsie: Vassar College, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Maria Teresa Bonadonna Russo. “I problemi dell’assistenza pubblica nel Seicento e il tentative di Mariano Sozzini.” Ricerche per la Storia Religiosa di Roma 3 (1979): 255–80. [Google Scholar]

- Franco Mormando. Bernini: His Life and His Rome. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lester L. Field. Liberty, Dominion, and the Two Swords: On the Origins of Western Political Theology (180–398). Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Charles L. Stinger. The Renaissance in Rome. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig Pastor. The History of the Popes from the Close of the Middle Ages. Vols. 1-40. St. Louis: Herder, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- William Kirwin. Powers Matchless: The Pontificate of Urban VIII, the Baldachin, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini. New York: P. Lang, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Andrea Nicoletti, and Leopold von Ranke. Della Vita di Papa Urbano VIII e Historia del Suo Pontificato Scritta da Andrea Nicoletti. Rome, 1650. [Google Scholar]

- Matthew Knox Averett. “The Annual Medals of Pope Urban VIII Barberini.” American Journal of Numismatics Second Series 25 (2013): 303–31. [Google Scholar]

- Giacinto DeMaria. “La Guerra di Castro e la spedizione de’ presidii (1639–49).” Miscellanea di Storia Italiana 35 (1898): 191–256. [Google Scholar]

- Jack Freiberg. “In the Sign of the Cross: The Image of Constantine in the Art of Counter-Reformation Rome.” In Piero della Francesca and His Legacy. Studies in the History of Art. No. 48; Edited by Marilyn Aronberg Lavin. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1995, pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Peter Rietbergen. Power and Religion in Baroque Rome. Barberini Cultural Policies. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- John France. The Crusades and the Expansion of Catholic Christendom, 1000–1714. London: Routledge, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick Hammond. Music and Spectacle in Baroque Rome: Barberini Patronage under Urban VIII. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher F. Black. Italian Confraternities in the Sixteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio Bernal. Copiosissimo Discorso della Fontana, e Guglia Eretta in Piazza Nauona, per Ordine della Santità di Nostro Signore Innocentio X. dal Signor Caualier Bernini. Rome: G. Tiberij, 1651. [Google Scholar]

- Genevieve Warwick. Bernini: Art as Theatre. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Luisa Cardilli. Feste e Spettacoli Nelle Piazze Romane. Rome: L’Instituto Libreria dello Stato, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Simon Werrett. Fireworks: Pyrotechnic arts and Sciences in European History. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Translated by Henry Joseph Schroeder. Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent. Rockford: Tan Books and Publishers, 1978.

- Alessandra Anselmi. “Theaters for the Canonization of Saints.” In St. Peter’s in the Vatican. Edited by William Tronzo. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 244–69. [Google Scholar]

- Irving Lavin. Visible Spirit: The Art of Gianlorenzo Bernini. London: Pindar Press, 2012, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Glen W. Bowerstock. “Peter and Constantine.” In St. Peter’s in the Vatican. Edited by William Tronzo. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Oskar Garstein. Rome and the Counter-Reformation in Scandinavia: The Age of Gustavus Adolphus and Queen Christina of Sweden, 1622–1656. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Camilla Kandare. “CorpoReality: Queen Christina of Sweden and the Embodiment of Sovereignty.” In Performativity and Performance in Baroque Rome. Edited by Peter Gillgren and Mårten Snickare. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2012, pp. 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Giacinto Gigli, and Manlio Barberito. Diario di Roma. Volume II, 1644–1670. Rome: Colombo, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold von Ranke. History of the Popes. New York: F. Ungar Publishing, 1966, vols. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Angela Groppi. “Roman Alms and Poor Relief in the Seventeenth Century.” In Rome, Amsterdam: Two Growing Cities in Seventeenth-Century Europe. Edited by Peter van Kessel and Elisja Schulte van Kessel. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1997, pp. 180–91. [Google Scholar]

- Brian S. Pullan. Poverty and Charity: Europe, Italy, Venice, 1400–1700. Aldershot and Hampshire: Variorum, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Bireley. The Refashioning of Catholicism, 1450–1700. Washington: The Catholic University of America Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- James Gordon Harper. “War and Peace in the Barberini Tapestries.” In I Barberini e la Cultura Europa del Seicento. Edited by Lorenza Mochi Onori, Sebastian Schütze and Francesco Solinas. Rome: DeLuca, 2007, pp. 431–46. [Google Scholar]

- Steven M. Cox, Jennifer M. Allen, Robert D. Hanser, and John J. Conrad. Juvenile Justice: A Guide to Theory, Policy, and Practice. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, Inc., 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Walter Miselli. Il Papato dal 1700–1730 Attraverso le Medaglie. Torino: Il Centauro, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Walter Miselli. Il Papato dal 1669–1700 Attraverso le Medaglie. Pavia: Numismatica Varesi, 2001. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).