Spirituality Self-Care Practices as a Mediator between Quality of Life and Depression

Abstract

:1. Introduction1

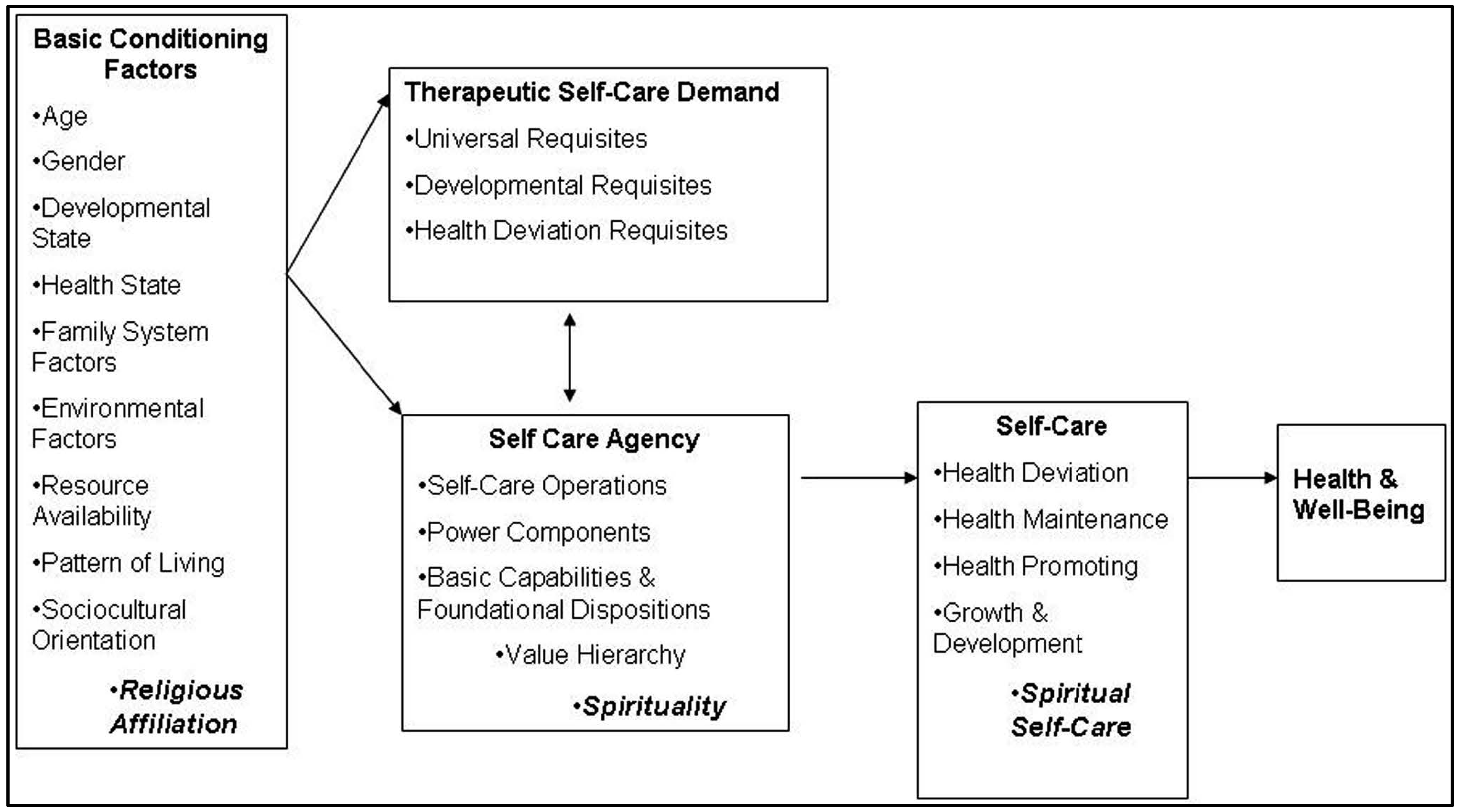

…descriptively explanatory of the relationship between the action capabilities of individuals and their demands for self-care or the care demands of children or adults who are their dependents. Deficit thus stands for the relationship between the action that individuals should take (the action demanded) and the action capabilities of individuals for self-care or dependent-care. Deficit in this context should be interpreted as a relationship, not as a human disorder.([7], p. 149)

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedures

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Implications for Nursing

6. Limitations of the Study

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mary L. White. “Spirituality self-care effects on quality of life for patients diagnosed with chronic illness.” Bulletin Luxembourgeois des Questions Sociales 29 (2012): 285. Available online: http://www.mss.public.lu/publications/blqs/blqs029/blqs_29.pdf#page=285 (accessed on 28 May 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Alyssa Easton. “Public-private partnerships and public health practice in the 21st century: Looking back at the experience of the Steps Program.” In Preventing Chronic Disease; 2009, 6, p. A38. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2687844/ (accessed on 15 May 2015). [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Freitas, Maria Célia, and Maria Manuela Rino Mendes. “Chronic health conditions in adults: Concept analysis.” Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 15 (2007): 590–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mary L. White, Rosalind Peters, and Stephanie Myers Schim. “Spirituality and Spiritual Self-Care Expanding Self-Care Deficit Nursing Theory.” Nursing Science Quarterly 24 (2011): 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mary J. Denyes, Dorothea E. Orem, and Gerd Bekel. “Self-care: A foundational science.” Nursing Science Quarterly 14 (2001): 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wayne Katon, and Paul Ciechanowski. “Impact of major depression on chronic medical illness.” In Journal of Psychosomatic Research; 2002, 53, pp. 859–63. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12377294 (accessed on 13 April 2015). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorothea E. Orem, Susan G. Taylor, and Kathie McLaughlin Renpenning. Nursing: Concepts of Practice. Mosby: St. Louis, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Michael B. First. “Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders.” In DSM IV, 4th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Harold G. Koenig. “Religion and remission of depression in medical inpatients with heart failure/pulmonary disease.” The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 195 (2007): 389–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucille Sanzero Eller, Inge Corless, Eli Haugen Bunch, Jeanne Kemppainen, William Holzemer, Kathleen Nokes, Carmen Portillo, and Patrice Nicholas. “Self-care strategies for depressive symptoms in people with HIV disease.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 51 (2005): 119–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Chronic Illness and Depression. Cleveland: Cleveland Clinic Foundation, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Paolo Cassano, and Maurizio Fava. “Depression and public health: An overview.” Journal of Psychosomatic Research 53 (2002): 849–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancy T. Artinian, Olivia GM Washington, John M. Flack, Elaine M. Hockman, and Kai-Lin Catherine Jen. “Depression, Stress, and Blood Pressure in Urban African-American Women.” Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing 21 (2006): 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. G. Cote, and Kenneth R Chapman. “Diagnosis and treatment considerations for women with COPD.” International Journal of Clinical Practice 63 (2009): 486–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Depression. Bethesda: National Institute of Mental Health, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- David R. Williams, Hector M. Gonzalez, Harold Neighbors, Randolph Nesse, Jamie M. Abelson, Julie Sweetman, and James S. Jackson. “Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life.” Archives of General Psychiatry 64 (2007): 305–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley Newlin, Kathleen Knafl, and Gail D’Eramo Melkus. “African-American spirituality: A concept analysis.” Advances in Nursing Science 25 (2002): 57–70. Available online: http://journals.lww.com/advancesinnursingscience/Abstract/2002/12000/African_American_Spirituality__A_Concept_Analysis.5.aspx (accessed on 28 May 2015). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun-Ju Liu, Ping-Chuan Hsiung, King-Jen Chang, Yu-Fen Liu, Kuo-Chang Wang, Fei-Hsiu Hsiao, Siu-Man Ng, and Cecilia LW Chan. “A study on the efficacy of body-mind-spirit group therapy for patients with breast cancer.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 17 (2008): 2539–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerstin Stake-Nilsson, Maud Söderlund, Rolf Hultcrantz, and Peter Unge. “A qualitative study of complementary and alternative medicine use in persons with uninvestigated dyspepsia.” Gastroenterology Nursing 32 (2009): 107–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colleen Delaney. “The spirituality scale development and psychometric testing of a holistic instrument to assess the human spiritual dimension.” Journal of Holistic Nursing 23 (2005): 145–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mary Jo Kreitzer, Cynthia R. Gross, On-anong Waleekhachonloet, Maryanne Reilly-Spong, and Marcia Byrd. “The Brief Serenity Scale A Psychometric Analysis of a Measure of Spirituality and Well-Being.” Journal of Holistic Nursing 27 (2009): 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mary L. White, and Stephanie Myers Schim. “Development of a spiritual self-care practice scale.” Journal of Nursing Measurement 21 (2013): 450–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHOQOL Group. “Development of the WHOQOL: Rationale and current status.” International Journal of Mental Health 23 (1994): 24–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anne M. McMahon. “Coping with chronic lung disease: Maintaining QOL.” In Coping with Chronic Illness: Overcoming Powerlessness, 3rd ed. Edited by Judith Fitzgerald Miller. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 2002, pp. 327–76. [Google Scholar]

- IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22.0). Windows; Armonk: IBM Corp., 2013.

- Bernd Löwe, Jürgen Unützer, Christopher M. Callahan, Anthony J. Perkins, and Kurt Kroenke. “Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9.” Medical Care 42 (2004): 1194–201. Available online: http://journals.lww.com/lww-medicalcare/Abstract/2004/12000/Monitoring_Depression_Treatment_Outcomes_With_the.6.aspx (accessed on 2 April 2015). [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kurt Kroenke, Robert L. Spitzer, and J. Williams. “The phq-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure [Electronic version].” In Journal of General Internal Medicine; 2001, 16, pp. 606–13. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pubmed/11556941 (accessed on 13 March 2015). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization QOL Group (WHOQOL). WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, Administration, Scoring, and Generic Version of the Assessment. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Susan M. Miller, Chan Fong, James M. Ferrin, Lin Chen-Ping, and Jacob Y.C. Chan. “Confirmatory factor analysis of the world health organization QOL questionnaire—Brief version for individual with spinal cord injury.” Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 54 (2008): 221–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben M. Baron, and David A. Kenny. “The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (1986): 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 1.Parts of the parent study have been presented at the 12th IOS World Congress on Future Nursing Systems; “New Approaches-New Evidence for 2020” in Luxembourg (2012). The demographic data also were included in the conference proceedings; Bulletin luxembourgeois des questions sociales [1].

| Demographic Characteristics | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 71 | 50.0% |

| Female | 71 | 50.0% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single, never married | 61 | 43.3% |

| Married | 36 | 25.5% |

| Widowed | 18 | 12.8% |

| Divorced | 24 | 17.0% |

| Living with partner | 2 | 1.4% |

| Educational Level | ||

| Less than high school | 30 | 21.6% |

| High school graduate/General Education Development | 56 | 40.3% |

| Some college/Technical school | 30 | 21.6% |

| Associate degree | 12 | 8.6% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 7 | 5.0% |

| Graduate degree | 4 | 2.9% |

| Work Status | ||

| Working full-time | 23 | 16.5% |

| Working part-time | 5 | 3.6% |

| Retired | 39 | 28.1% |

| Retired, volunteering | 2 | 1.4% |

| Disabled | 44 | 31.7% |

| Other | 26 | 18.7% |

| Living Arrangements | ||

| Spouse | 40 | 28.8% |

| Children | 25 | 18.0% |

| Alone (independently) | 43 | 30.9% |

| Assisted living facility | 2 | 1.4% |

| Senior residence | 1 | 0.7% |

| Other family/friends | 28 | 20.1% |

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Personal Self-Care Practices | ||||

| Making time for self | 0.71 | |||

| Eating healthy foods | 0.67 | |||

| Feeling at peace and/or in harmony | 0.66 | |||

| Resting to regain health and energy | 0.65 | |||

| Giving love to others | 0.58 | |||

| Following medical orders | 0.57 | |||

| Maintaining a sense of hope for the future | 0.57 | |||

| Laughing | 0.56 | |||

| Forgiving yourself | 0.56 | |||

| Finding meaning in both good or bad situations | 0.51 | |||

| Maintaining positive relationships | 0.50 | |||

| Asking questions about medical orders | 0.50 | |||

| Forgiving others | 0.43 | |||

| Helping others | 0.43 | |||

| 2. Spiritual Practices | ||||

| Attending religious services | 0.75 | |||

| Contributing to a religious group | 0.70 | |||

| Praying | 0.68 | |||

| Consulting a spiritual advisor | 0.66 | |||

| Living a moral life | 0.59 | |||

| Meditating, contemplating, or reflecting | 0.55 | |||

| Reading for inspiration | 0.54 | |||

| Mending broken relationships | 0.40 | |||

| Resolving conflicts | 0.38 | |||

| 3. Physical Spiritual Practices | ||||

| Engaging in physical activity | 0.77 | |||

| Giving alms to the poor or doing other acts of charity | 0.55 | |||

| Volunteering | 0.54 | |||

| Hiking or walking | 0.50 | |||

| Practicing yoga or tai-chi | 0.36 | |||

| 4. Interpersonal Spiritual Practices | ||||

| Following a special diet (e.g., Kosher, Halal, vegetarian, etc.) | 0.66 | |||

| Maintaining friendships | 0.56 | |||

| Being with family | 0.52 | |||

| Having a meaningful conversation with others | 0.47 | |||

| Receiving love from others | 0.46 | |||

| Being with friends | 0.46 | |||

| Wearing special clothing or jewelry (yarmulke, burqa, cross, Star of David, etc.) | 0.44 | |||

| Percent of explained variance | 30.23 | 6.90 | 5.35 | 4.77 |

| Cronbach alpha coefficients | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.69 | 0.66 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual Self-care Practices | 3.79 | 0.59 | 2.31 | 4.83 |

| Depression | 1.68 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 3.75 |

| Quality of Life | 3.82 | 0.70 | 1.72 | 4.89 |

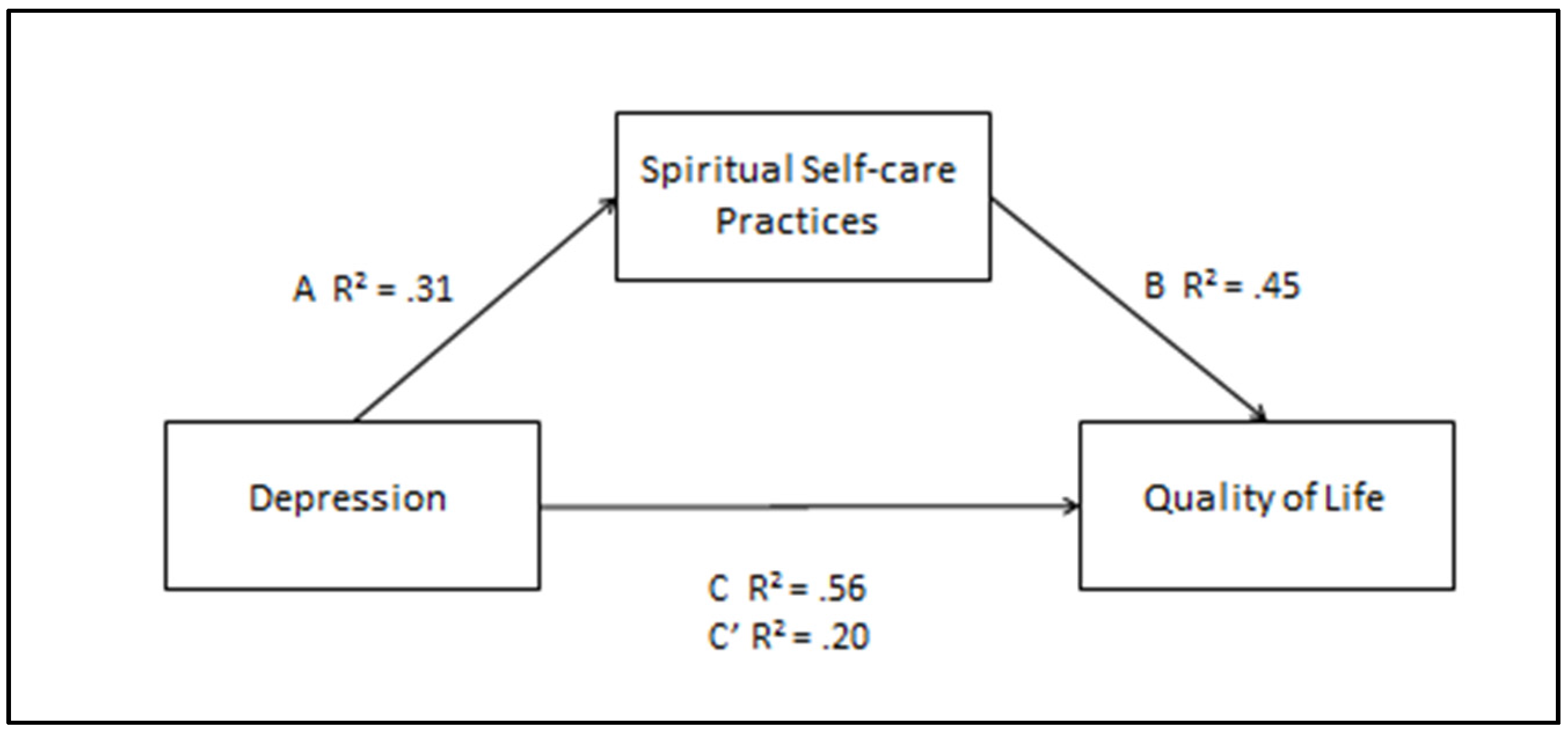

| Step | Predictor | Outcomes | R2 | F | Standardized β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Depression | QOL | 0.56 | 174.21 | −0.75 ** | |

| 2 | Depression | Spirituality Self-care Practices | 0.31 | 62.49 | −0.56 ** | |

| 3 | Spirituality Self-care Practices | QOL | 0.45 | 110.15 | 0.67 ** | |

| 4 | (a) | Spirituality Self-Care Practices | QOL | 0.45 | 110.15 | 0.67 ** |

| (b) | Depression | QOL | 0.20 | 126.32 | −0.55 ** | |

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

White, M.L. Spirituality Self-Care Practices as a Mediator between Quality of Life and Depression. Religions 2016, 7, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7050054

White ML. Spirituality Self-Care Practices as a Mediator between Quality of Life and Depression. Religions. 2016; 7(5):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7050054

Chicago/Turabian StyleWhite, Mary L. 2016. "Spirituality Self-Care Practices as a Mediator between Quality of Life and Depression" Religions 7, no. 5: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7050054

APA StyleWhite, M. L. (2016). Spirituality Self-Care Practices as a Mediator between Quality of Life and Depression. Religions, 7(5), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7050054