Abstract

Congregations and other religious organizations are an important part of the social welfare system in the United States. This article uses data from the 2012 National Congregations Study to describe key features of congregational involvement in social service programs and projects. Most congregations (83%), containing 92% of religious service attendees, engage in some social or human service activities intended to help people outside of their congregation. These programs are primarily oriented to food, health, clothing, and housing provision, with less involvement in some of the more intense and long-term interventions such as drug abuse recovery, prison programs, or immigrant services. The median congregation involved in social services spent $1500 per year directly on these programs, and 17% had a staff member who worked on them at least a quarter of the time. Fewer than 2% of congregations received any government financial support of their social service programs and projects within the past year; only 5% had applied for such funding. The typical, and probably most important, way in which congregations pursue social service activity is by providing small groups of volunteers to engage in well-defined and bounded tasks on a periodic basis, most often in collaboration with other congregations and community organizations.

1. Introduction

The most lasting and important legacy of the second Bush administration’s Faith-Based Initiative is the large body of research it inspired about religious organizations’ place in our social welfare system. The Faith-Based Initiative did not change much on the ground. Religious organizations, including congregations, were an important part of our social welfare system long before the initiative, and they still are. Religious organizations, including congregations, received public funding to support social service activities long before the initiative, and they still do. All in all, religion’s contributions to our social welfare system have not changed much since before the Faith-Based Initiative but, thanks to the research inspired by the initiative, we know much more about these contributions than we did before [1,2,3].

In this article we focus on congregations’ social service activities. Research and writing on this subject in the midst of the Faith-Based Initiative was shaped by the policy debate, with those sympathetic to the initiative emphasizing the extent of social services performed by congregations and how much more they might be capable of doing, while those unsympathetic to the initiative emphasized how little social services congregations did, and the limits of what they reasonably could be expected to do [4,5,6,7,8]. With the fading of the Faith-Based Initiative, it now is clear that the policy debate obscured a fair degree of consensus concerning the basic facts about the extent and limits of congregations’ social service work. Here we use data from the 2012 National Congregations Study to describe several key features of congregations’ contemporary social service activity.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data

The National Congregations Study (NCS) is a survey of a nationally representative sample of religious congregations from across the religious spectrum, conducted in 1998, 2006, and 2012. In those years, the General Social Survey (GSS)—a well-known in-person survey of a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized, English- or Spanish-speaking adults conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago [9]—asked respondents who said they attend religious services at least once a year where they worship. The congregations named by these people constitute a representative cross-section of American congregations. The NCS then contacted those congregations and interviewed someone, usually a clergyperson or other leader, about the congregation’s people, programs, and characteristics. Between the three waves of the NCS we now know about the demographics, leadership situation, worship life, programming, surrounding neighborhood, and more, of 3815 congregations.

The 2012 NCS (NCS-III) gathered data from 1331 congregations. The cooperation rate—the percentage of contacted congregations who agreed to participate—was 87%. The overall response rate, calculated in line with the RR3 response rate developed by the American Association for Public Opinion Research [10], but not taking account of the GSS’s own response rate, is between 73% and 78%. We report a range because the exact response rate depends on assumptions about the congregations associated with GSS respondents who declined to nominate a congregation after stating that they attended more than once a year.

The probability that a congregation appears in the NCS-III sample is proportional to its size: larger congregations are more likely to be in the sample than smaller congregations. Using weights to retain or undo this over-representation of larger congregations corresponds to viewing the data either from the perspective of attendees at the average congregation or from the perspective of the average congregation, without respect to its size. More information about this and other NCS methodological details is available elsewhere [11,12,13,14].

2.2. Variables

The 2012 NCS asked congregational informants, “Has your congregation participated in or supported social service, community development, or neighborhood organizing projects of any sort within the past 12 months?” Respondents were instructed to exclude any “projects that use or rent space in your building but have no other connection to your congregation.” Any numerical estimate of the extent of congregations’ social service activity depends on the exact way questions are asked and the extent of probing, and we know that more informal social service activities remain underreported without additional probing. Recognizing this, respondents who said “no” to this initial social services question were also asked, “Within the past 12 months, has your congregation engaged in any human service projects, outreach ministries, or other activities intended to help people who are not members of your congregation?” Congregations responding “yes” to either of these questions are considered to be engaged in social service activity of some sort.

In 2012, respondents who said “yes” to either of these questions were asked how many programs they sponsored or participated in within the last year. If they said four or fewer, they were asked to describe each program in an open-ended way. If they said more than four, they were asked to describe their four most important programs. The median number of programs reported was two for all congregations and three for congregations reporting some social service activity, with 73% of the latter reporting four or fewer programs. Five percent of congregations reported 15 or more distinct social service programs.

Interviewers were instructed to probe for each mentioned program’s purpose (up to four programs), and they recorded verbatim the descriptions offered by the respondent. These verbatim descriptions were coded into a set of non-mutually-exclusive variables, each one indicating a specified program characteristic or area. Substantively, these variables indicate congregational participation in a wide variety of arenas, including food, clothing, health, housing, disaster relief, domestic violence, prisons, employment, and immigration. Two coders independently coded each verbatim response, with disagreements resolved by a referee.

Congregations that mentioned social service activity were asked follow-up questions about how these activities were supported. For each program mentioned (up to four), informants were asked “whether it is a program or project completely run by your congregation, or whether it is a program that is run by or in collaboration with other groups or organizations.” Additional questions were asked regarding all of a congregation’s social service programs, not just its most important four: how much money was directly spent by the congregation on all of the programs, whether or not a staff person devoted at least 25% of his or her time in the past 12 months to these projects, whether the congregation received outside funds to support these activities, whether any outside funds came from government sources, and whether the congregation applied within the last two years for a government grant to support any of these activities. These items help us to assess the depth of congregational involvement in social services.

Two additional items in the NCS survey help assess congregational interest in social services: whether they have had a representative of a social service organization as a visiting speaker in the past year, and whether within the past year they had a group, meeting, class, or event to plan or conduct an assessment of community needs.

To assess differences across religious groups in social service activity, we use a modified version of a standard categorization [15] of congregations into five broad religious traditions: Roman Catholic, white liberal/mainline Protestant, white conservative/evangelical Protestant, black Protestant, and non-Christian congregations. These subgroups were constructed based primarily on denominational affiliations. Protestant congregations with at least 80% of the regularly participating adults of African or African American descent were placed in the black Protestant category, regardless of denomination. White Protestant congregations unaffiliated with any denomination were placed in the evangelical category.

2.3. Assessing Change over Time

Brad Fulton’s article in this volume [16] examines stability and change in congregations’ social service activity, so we will not say much about changes between 1998 and 2012. Still, we should mention two methodological details that are relevant for assessing change over time with these data.

First, the two-question strategy described above to identify congregations doing any social services is the same one used in the 2006 NCS, but different from the approach used in the 1998 NCS, when congregations were asked only the first of these questions. This means that assessing change since 1998 requires constructing 2006 and 2012 numbers that are comparable to 1998 numbers. This can be done by ignoring responses to the follow-up question and analytically treating the 2006 and 2012 congregations that said “no” to the initial question the same way they were treated in 1998.

Second, the 1998 and 2006 NCS surveys allowed congregations to name and describe all of their social service programs, with no limit. The 2012 NCS limited these descriptions to a congregation’s most important four programs. As noted above, even in 2012, questions about funding and staff support were asked with all congregational programs in mind, not just the most important four, so responses to those questions are in principle comparable over time, although interpretive caution still is advised since the context in which those questions were asked was not identical. Even more caution should be used when interpreting results implying change over time that are produced with information that was gathered about every program in 1998 and 2006 but only about the most important four programs in 2012. This includes information about specific program areas and information about collaborators. If, for example, a congregation’s fifth most important program was aimed at helping people get jobs, that congregation would be coded as having a jobs program in 1998 and 2006 but not in 2012. Researchers using these data to investigate change over time should keep these details in mind.

3. Results

Congregations focus most of their time and resources on worship services, religious education, and pastoral care of their members. At the same time, however, almost all also serve the needy beyond their walls in some fashion. In 2012, the vast majority of congregations (83%) reported some involvement in social or human services, community development, or other projects and activities intended to help people outside the congregation. Since larger congregations are more likely to engage in social service work, this means that virtually all Americans (92%) who attend religious services attend a congregation that is somehow active in this way. Mainline Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Jewish congregations are somewhat more likely to report social service activity (approximately 90% in each group) than evangelical or black Protestant congregations (approximately 80% in each group). This difference is statistically significant at p < 0.05. Among Christian traditions, a regression analysis shows that this difference occurs because there are more small, rural, and less-wealthy churches in the latter two groups. Regardless of these characteristics, Jewish congregations were more likely to be involved in social service activity. In any event, the vast majority of congregations in each of these religious traditions engages in some sort of social service work.

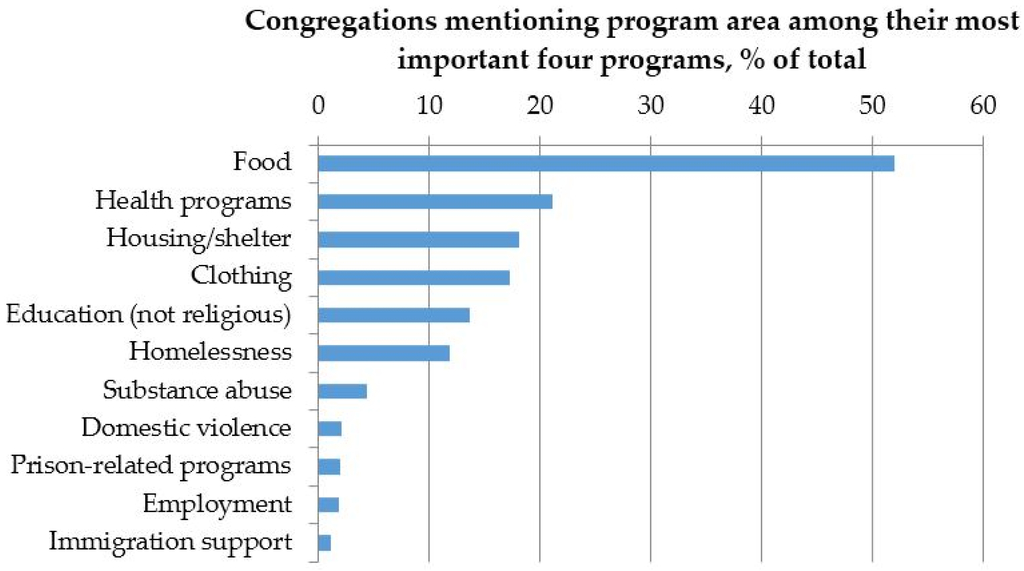

Congregations participate in a great variety of social service activities, but some types of activities are much more common than others. Figure 1 shows the variation. The single most common kind of helping activity involves food assistance, with more than half (52%) of all congregations—almost two-thirds (63%) of congregations active in social service—mentioning feeding the hungry among their four most important social service programs. Addressing health needs (21%), building or repairing homes (18%), and providing clothing or blankets to people (17%) also were among the more commonly mentioned activities, though they were much less common than food assistance. Even more rarely mentioned by congregations as one of their most important four social service projects are those requiring longer-term commitments and more intensive interaction with the needy. Programs aimed at helping prisoners, victims of domestic violence, the unemployed, substance abusers, and immigrants, for example, each are listed by fewer than 5% of congregations as one of their most important four programs, and only 11% of congregations place any one of these activities on their top-four list.

Figure 1.

Congregational participation in selected social service program areas, 2012.

These results show that congregations are involved in an impressive range of activities, but categories like “food assistance” or “housing/shelter” encompass a great deal of variation both in the nature of the specific activity and in the intensity of congregational involvement in that arena. Food assistance, for example, includes donating money to a community food bank, participating in a Crop Walk fundraiser, supplying volunteers who serve dinner at a homeless shelter once a month, or operating a food pantry or soup kitchen. Congregations might address housing needs by organizing a team of volunteers to participate in a Habitat for Humanity project, or they might partner with city government to build affordable housing. Health assistance includes providing wheelchair ramps or home cleaning for disabled people, hosting health fairs or speakers on health-related issues, or supporting water projects in developing countries.

Table 1 helps us assess the depth of congregations’ social service involvement. Its three panels provide information about the extent to which congregations are involved at all in social services, the extent to which they display an interest in social services that is serious enough to have had an outside speaker from a social service organization or a group that conducted a community needs assessment, and the extent to which they are more deeply involved in social services.

Table 1.

Involvement in social services by religious congregations in the USA, 2012.

As we noted above, the vast majority of congregations—83%, containing 92% of religious service attendees—report some manner of social service involvement by saying “yes” to one of the NCS’s two basic questions asking about such involvement. More than half (57%) say that they conducted a community needs assessment in the last year, and almost one third (31%) say that they had a visiting speaker in the last year who represented a social service organization. Although, as we noted earlier, we will not focus in this article on stability and change over time, it is worth noting that a larger percentage of congregations displayed interest in social services in 2012 than in 1998. In 1998, only 22% of congregations had a speaker from a social service agency and only 37% reported having done a community needs assessment in the last year. In 2006, the percentages were 31% and 48%, respectively. Both of those increases are statistically significant. Congregations appeared to be somewhat more interested in social services and in government funding in 2012 than they were in 1998, perhaps reflecting the fact that the Faith-Based Initiative captured people’s attention and, to some extent, their imaginations, even if it changed little, if anything, about the nature and extent of congregational involvement in social services. (See Brad Fulton’s article in this volume [16] for a more detailed assessment of changes since 1998 in congregations’ social service activities.)

The bottom panel of Table 1 shows that, despite nearly universal involvement in some sort of social service activity and relatively high levels of interest in the needs of their surrounding communities and the wider world of social service organizations, congregations’ social service activities typically fall on the less intensive side of the range of activities mentioned above. Only 14% of congregations have at least one staff member devoting at least a quarter of their work time to social service projects. And, even excluding congregations who say that they do no social services, the median congregation in 2012 spent only $1500 directly on its social service activities, which amounts to about 2% of the average congregation’s budget.

Looking at other indicators of a deeper involvement in social services, 9% of congregations had at least one program supported with outside funding. Especially in light of all the media and research attention given the Faith-Based Initiative, congregational participation in government funding for social services seems strikingly low. Fewer than 2% of congregations had programs supported by a grant from a local, state, or national government agency, and only 5% had applied for a government grant within the last two years, while 9% of congregations reported starting a nonprofit organization focused on human services or outreach in that same time period. All of these numbers, not incidentally, are qualitatively similar to comparable NCS numbers from both 1998 and 2006, as Brad Fulton documents elsewhere in this volume [16]. The Faith-Based Initiative did not increase congregational receipt of public funds in support of their social service activity.

4. Discussion

Many of the numbers we report above might seem small, but they in fact represent a substantial amount of congregational contribution to community well-being. The $1500 of direct congregational spending on their social service programs, for example, may not include special offerings congregations often gather for specific charitable purposes, the dollar value of their in-kind contributions to community organizations, or the dollar value of staff time in congregations where staff work on social service projects. Of course, congregations also support social service work through donations to denominational social service organizations like Catholic Charities, Lutheran Social Services, and Jewish Family Services.

Calculating the total monetary value of the material contributions congregations make to communities outside their own walls is very difficult. Jeff Biddle, drawing on data from a variety of sources, estimated that congregations spend 29% of their income on what he called “philanthropic activities” [17]. This estimate probably overstates congregations’ spending beyond their own walls. Other calculations suggest that congregations spend only about 15% of their income on things other than running the local congregation [18,19]. But these low estimates assume that all of the money that congregations give to their denominations and other mission organizations is for charitable purposes, and conversely they assume that none of the money that congregations spend on their own operations benefits people beyond the membership. Neither of these assumptions is accurate. Some of the money that congregations send to their denominations supports organizational infrastructure and activities aimed mainly at members, such as seminary education for future leaders, regional and national offices of a denomination, or annual meetings of the denomination. On the other hand, some money spent on a congregation’s local operations benefits people other than members, as when a clergyperson or other paid staff member spends time on a community project or when a community group uses a congregation’s building for little or no charge. This accounting also misses other kinds of publicly beneficial action commonly taken by congregations, such as when they gather a special collection for an unbudgeted charitable purpose like disaster relief or organize members for volunteer work of various sorts. Another attempt to take more of this activity into account concluded that congregations spent 23% of their annual budgets on social and community service ([4], p. 88). The most prudent conclusion given the current state of knowledge is that between 15 and 30 percent of congregational income is spent in ways that benefit non-members.

Whatever the precise number, congregations clearly contribute a lot of material resources to their local communities and beyond. If we use the most conservative estimate mentioned in the previous paragraph—that beyond the 2% in direct cash outlays on social services, 15% of congregational income is spent in ways that benefit nonmembers—it would mean that about $17 billion of the $115 billion given to religious organizations in 2014 benefited non-members [20]. This estimate is too high since $115 billion was given to all religious organizations, not just congregations. A more conservative estimate would take 15% of the $22.1 billion contributed to congregations in a large but not complete subset of denominations in 2013 ([19], pp. 1, 17), yielding $3.3 billion spent by congregations in ways that benefit nonmembers. This number probably is too low, since it is based on an estimate of total giving to congregations that does not include all congregations, but even by this conservative estimate, it is clear that congregations’ financial contributions to their communities are substantial in absolute terms.

Several other numbers in Table 1 similarly represent substantial contributions. There are more than 300,000 congregations in the United States. If 14% of all congregations have a staff person devoting quarter time to social services, that means that more than 40,000 congregations are engaged in that way. If 9% started a nonprofit organization devoted to human services in the last two years, this means that congregations created more than 27,000 new social service organizations in the last two years. Since a small percentage of a large number equals a large number, the relatively small percentages of congregations that are more deeply engaged in social services still adds up to a substantial amount of activity.

A comparative perspective also provides helpful context for understanding the extent of congregations’ contributions. The basic observation here is that congregations’ level of social service involvement compares favorably to levels of effort observed in other organizations whose main purpose, like congregations, is something other than charity or social service. In what other set of organizations whose primary purpose is something other than charity or social service do the vast majority engage in at least some social service, however peripherally? In what other organizational population do as many as 52% somehow help to feed the hungry, 17% distribute clothing, 12% serve the homeless, or 14% have staff devoting at least a quarter of their time to social service activities?

Burton Weisbrod’s “collectiveness index” helps us compare congregations to other organizations in this regard [21]. This index measures the percentage of an organization’s revenue that comes from contributions, gifts, and grants rather than from either sales or membership dues. The logic is that an organization is more publicly beneficial the more it benefits individuals beyond its own customers, members, or constituents, and that income from contributions, gifts, and grants measures that propensity. The estimates of congregations’ philanthropic contributions described above can be understood as implying a “collectiveness” score for congregations of between 15 and 30. That is, if 15% of congregations’ income is spent trying to improve the well-being of nonmembers, we can say that 85% of member donations can be understood as “dues” and 15% as a “gift” that supports congregations’ publicly beneficial activities. Estimates of congregational spending beyond their walls that come out on the high side—closer to 30%—place congregations in the same vicinity as organizations primarily engaged in welfare (which score 43), advocacy (40), instruction and planning (37), and housing (31). Calculations that come out more on the low side still place congregations in the respectable company of Meals on Wheels (16), as well as organizations primarily engaged in legislative and political education (18), or general education (18).

Even the 2% of their income that congregations spend directly on social services looks impressive in comparative perspective. What other organizations whose primary purpose is something other than social service devote, on average, as much as 2% of their income to social services? To offer one comparison, corporations devote only about 1% of their pretax profits to charity. In absolute terms the $17.8 billion in charitable donations given by corporations in 2014 [20] probably amounts to more than the total amount given by congregations, but, as a proportion of total income, congregations’ public-serving activity compares well to the charitable activity of other organizations whose main purpose is neither charity nor social service.

All this said, the typical and probably most important way in which congregations pursue social service activity is not with direct financial contributions. It is by organizing small groups of volunteers to carry out well-defined tasks on a periodic basis. Examples abound: fifteen people spending several Saturdays renovating a house, five people cooking and serving dinner to the homeless one night a week, ten young people spending a summer week painting a school, ten people traveling to the sight of a natural disaster to provide assistance for a week, a couple of dozen people raising money in a Crop Walk, and so on. In this light, it is no accident that congregations are most active in areas like food assistance and home repair in which small groups of volunteers focused on a bounded task can be put to best use. Congregations are very good—perhaps uniquely good in American society—at mobilizing volunteers for this kind of work, work that usually is done, not incidentally, in collaboration with other congregations or service organizations rather than alone. In 2012, 75% of congregations that reported any social service activity collaborated with other congregations or service organizations on at least one of their most important four programs.

Volunteer-based action has limits, of course, and attempts to push congregation-based volunteers beyond these limits (such as attempting to engage them in open-ended mentoring relationships with women transitioning from welfare to work) are fraught with difficulties [22], but congregations are and will continue to be valuable participants in our social welfare system, especially in collaboration with social service organizations able to use what congregations are best able to supply: small groups of volunteers charged with tasks that are well defined and bounded in scope and time.

5. Conclusions

All things considered, a fairly clear and stable picture has emerged about the extent, nature, and limits of congregations’ social service activities. Most congregations focus primarily on their religious activities: worship services, religious education, and pastoral care for their own members. Virtually all also do something that can be considered social service, social ministry, or human service work. Some congregations do quite a lot of this, and a small percentage even receive government grants to support such work, but for the vast majority of congregations such activity remains a more peripheral, volunteer-driven part of what they do. Most congregational involvement in social service activity occurs in collaboration with other community organizations, and most activity is focused on meeting short-term, immediate needs, especially the need for food. The most typical, and important, form in which congregations engage in social services is by mobilizing small groups of volunteers to engage in well-defined and bounded tasks on a periodic basis.

Even though social service involvement is not their primary activity, congregations make impressive contributions in this arena. Few other organizations, aside from those whose express purpose is social service, conduct assessments of community needs and raise awareness of such to the same extent. The amount of time that paid staff and congregation-based volunteers devote to service outside the congregation itself are also significant contributions. This is the picture consistently painted by the NCS and by other research on congregations’ social services. Freed from the need to discern this picture’s implications for a politicized Faith-Based Initiative, we can more easily establish a common ground of knowledge and understanding about congregations’ social service work.

Acknowledgments

The NCS was made possible by major grants from the Lilly Endowment, Inc. The 2012 NCS also was supported by grants from the Pew Research Center’s Religion and Public Life Project, Louisville Institute, Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture at IUPUI, Rand Corporation, and Church Music Institute. The project also received generous support from Duke University and from the National Science Foundation via NSF support of the General Social Survey. Data were gathered by NORC at the University of Chicago. Shawna Anderson managed large portions of the project in the initial stages of data collection.

Author Contributions

Mark Chaves is the principal investigator for the National Congregations Study. Alison Eagle is the project manager. Alison Eagle analyzed the data. Both authors contributed to the writing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GSS | General Social Survey |

| NCS | National Congregations Study |

References

- Jo Anne Schneider. “Introduction to the Symposium: Faith-Based Organizations in Context.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 42 (2013): 431–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfgang Bielefeld, and William Suhs Cleveland. “Defining Faith-Based Organizations and Understanding Them through Research.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 42 (2013): 442–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark Chaves, and Bob Wineburg. “Did the Faith-Based Initiative Change Congregations? ” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 39 (2010): 343–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram A. Cnaan, Stephanie C. Boddie, Femida Handy, Gaynor Yancey, and Richard Schneider. The Invisible Caring Hand: American Congregations and the Provision of Welfare. New York: New York University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Chaves. Congregations in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004, chap. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Chaves, and William Tsitsos. “Congregations and Social Services: What They Do, How They Do It, and with Whom.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 30 (2001): 660–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bob Wineburg. A Limited Partnership: The Politics of Religion, Welfare, and Social Science. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bob Wineburg. Faith-Based Inefficiency: The Follies of Bush’s Initiatives. Westport: Praeger, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tom W. Smith, Peter V. Marsden, and Michael Hout. General Social Surveys, 1972–2012: Cumulative Codebook. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys, 5th ed. Lenexa: AAPOR, 2008, p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Chaves, and Shawna L. Anderson. “Changing American Congregations: Findings from the Third Wave of the National Congregations Study.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53 (2014): 676–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark Chaves, and Shawna L. Anderson. “Continuity and Change in American Congregations: Introducing the Second Wave of the National Congregations Study.” Sociology of Religion 69 (2008): 415–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark Chaves, Mary Ellen Konieczny, Kraig Beyerlein, and Emily Barman. “The National Congregations Study: Background, Methods, and Selected Results.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 38 (1999): 458–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark Chaves. “National Congregations Study.” Available online: www.soc.duke.edu/natcong (accessed on 23 February 2016).

- Brian Steensland, Jerry Z. Park, Mark D. Regnerus, Lynn D. Robinson, W. Bradford Wilcox, and Robert D. Woodberry. “The Measure of American Religion: Toward Improving the State of the Art.” Social Forces 79 (2000): 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brad R. Fulton. “Trends in Addressing Social Needs: A Longitudinal Study of Congregation-Based Service Provision and Political Participation.” Religions 7 (2016): article 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeff E. Biddle. “Religious Organizations.” In Who Benefits from the Nonprofit Sector. Edited by Charles T. Clotfelter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992, pp. 92–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dean R. Hoge, Charles Zech, Patrick McNamara, and Michael J. Donahue. Money Matters: Personal Giving in American Churches. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1996, p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- John L. Ronsvalle, and Sylvia Ronsvalle. The State of Church Giving through 2013: Crisis or Potential? Champaign: Empty Tomb, Inc., 2015, p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. Giving USA: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2014. Chicago: Giving USA Foundation, 2015, pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Burton A. Weisbrod. The Nonprofit Economy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988, pp. 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Paul Licherterman. Elusive Togetherness: Church Groups Trying to Bridge America’s Divisions. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005, chap. 5. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).