1. Introduction

In August of 2009, American Catholic Bishops laid out three primary policy goals for health care reform in the United States: it would not deliver any federal funds for abortion, it would increase coverage for the poor and it would allow immigrants (in the country legally or illegally) to receive benefits. When President Barack Obama signed the Affordable Care Act into law, only one of those policy goals (increasing coverage for the poor) was realized. Likewise, in November 1995, the United States Catholic Bishops issued a statement of moral principles for welfare reform, intended to serve as a guideline for policymakers. When President William Clinton signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), which ended the entitlement to welfare, it too did not meet the initial guidelines set out by the bishops. Although the bishops were quite public in their statements about health care and welfare reform, and although their staff lobbied and testified before Congress on their behalf, the Catholics—as represented by the bishops’ statements—failed to achieve the kind of policy reform that they were looking for. On the other hand, as we shall see, the voices of the Catholic groups (especially in health care) played at least some role in framing the debate around specific issues and drawing attention to matters of moral concern.

These policy reforms in the late 20th and early 21st centuries were not the first time Catholic interest groups had involved themselves in the policy process, nor are the Catholics the first or only religious group to lobby government. In fact, the United States has a long history of religious influence on public policy: the anti-slavery movement, progressivism, prohibition, civil rights, abortion, school vouchers, school prayer and nuclear disarmament are all issues that have involved religion and religious groups in policymaking [

1,

2,

3]. From their early history until today, religious groups have proliferated and involved themselves in several aspects of the policy process. A major study released by Pew Research in 2011 categorized various types of religious groups and noted the greatly increased numbers of such groups in the past several decades:

The number of organizations engaged in religious lobbying or religion-related advocacy in Washington, DC, has increased roughly fivefold in the past four decades, from fewer than 40 in 1970 to more than 200 today. These groups collectively employ at least 1000 people in the greater Washington area and spend at least $350 million a year on efforts to influence national public policy. As a whole, religious advocacy organizations work on about 300 policy issues.

While we know that there are many (and many different types of) religious interest groups, and that they may be involved at various levels of government and in various types of advocacy, there still is not a great deal of attention to

how they go about the business of lobbying, particularly in the national arena [

5]. This article is an attempt to place religious (specifically Catholic) interest groups in the context of the interest group literature, by examining their role in two case studies, welfare reform in 1996 and health care reform in 2011. As such, the article asks the following questions: how are religious interest groups similar to and different from other interest groups? What tactics do they use? How successful are they? Under what conditions is success or failure more likely? This article will operate under the assumption that religious interest groups are appropriately involved in the political process, a point that has been well-articulated elsewhere [

6,

7], and instead will attempt to examine the groups as interest groups. First, it will place Catholic interest groups in the context of the interest group literature, and, second, it will examine the role that Catholic interest groups played in the passage of welfare reform in 1996 and in the passage of health care reform in 2010. These cases were chosen for two reasons.

- (1)

Catholic interest groups initially formed around the issue of welfare and its attendant issue of health care for the poor. As we shall see, Catholic charities developed as an interest group as the various charities it represented attempted to deal with the growing demands of impoverished immigrant Catholics on the church in the United States.

- (2)

The Catholic Bishops were not overtly successful in a policy sense in either case. By examining such cases, we can see the constraints that the Catholic interest groups faced. By addressing the conditions under which lobbying was not successful, perhaps we may be better able to understand the factors that make for success.

Throughout the article, the Catholic interest groups will be treated as elite actors in the policy process. Although the relationship between the interest groups and their rank and file (American Catholics) will be touched on, the article is more interested in the lobbying activities of the interest groups themselves.

The next section describes the Catholic interest groups. A discussion of the interest group literature follows. We then turn to an evaluation of Catholic groups as interest groups, first by making some hypotheses and then analyzing the role of these groups in welfare and health care reform through contemporary newspaper accounts and interviews. We conclude with a discussion of the constraints faced by interest groups in the policymaking process.

3. Interest Group Theory and Catholic Interest Groups

The political science literature on interest groups examines them in several different ways: it classifies their membership and goals, it theorizes about their formation, it examines their resources and techniques and assesses their impact. Each of these aspects of interest groups will be addressed in turn.

3.1. Membership/Classification

The interest group literature classifies interest groups according to their membership and goals. Groups may be membership-based, public interest groups, or institutional groups. Jack Walker divides interest groups into two main categories: occupational and non-occupational, depending on whether or not membership is open [

10]. Non-occupational groups are those groups to whom membership is open to anyone who wishes to join. Occupational interest groups, on the other hand, are those groups whose membership is based on profession. Clearly, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops is a group whose membership is based on occupation—you have to be a bishop to be a member. Likewise, Catholic Charities is made up of the various groups that provide charitable services in the name of the Catholic Church, the Catholic Health Association is made up of professionals from Catholic hospitals and Network is made up of nuns representing several religious orders, with a post-Vatican II focus on justice. Walker further divides occupational groups into the profit sector, the non-profit sector, and the mixed sector. Again, the Catholic interest groups easily fit into the non-profit sector classification, and are classified as such for tax purposes.

The Pew Research report classifies religious groups into five categories: membership groups institutional groups, official religious bodies, think tanks, permanent coalitions and hybrid groups which fall into more than one category. By Pew’s classification, the USCCB is an “official religious body” rather than a membership group, which is made up of individual church members, or rank and file, if you will. [

11].

Narrowly defined, however, the Catholic interest groups are membership groups of bishops, nuns or social service providers, and as such, are professional associations, as noted by Allen Hertzke [

12]. More broadly, however, the Catholic interest groups may be said to represent the Church as a whole, which would include the Catholic laity as well as the Catholic leadership. In this sense, the membership of the groups would be much larger, and much more difficult to analyze. Although catholic means universal, the church is by no means unanimous in its public opinion. In addition, the hierarchy is often at odds with the rank and file congregants. Looked at as a hierarchical institution, however, the Catholic Church ceases to be a membership interest group and becomes an institutional group, representing a hierarchical institution, in the same way that a corporation or university might hire a Washington lobbyist [

13]. Is the Catholic Church an institutional group or a membership group? Timothy Byrnes gets around this dilemma by creating a hybrid category called “membership institution” to describe church interest groups which represent both their hierarchy and their members [

14]. While his distinction is useful, we prefer to separate the Catholic interest groups from the Catholic Church as a whole. We view them as occupational interest groups, rather than broad-based membership groups or institutional groups, for several reasons.

- (1)

The constitutional makeup of the groups lends itself to this classification. The USCCB calls itself the conference of Catholic bishops, not the conference of Catholics. The bishops represent the church, and the name and make-up of their interest group makes it clear that they represent the church hierarchy, not the church membership. Similarly, the Catholic Health Association, Network and Catholic Charities USA represent their member organizations, not the church at large.

- (2)

The activities of the interest groups—at least in the policy arena—lend themselves to these classifications. The USCCB puts out pastoral letters, which have as one purpose influencing public policy. Another purpose is instruction of (not representation of) the Catholic laity.

- (3)

Such a view makes for easier analysis. The USCCB, which presents itself as the conference of bishops can be analyzed as such, not as a group attempting to represent the public opinion of the church as a whole. (The bishops seem more likely to attempt to influence the public opinion of the church than represent it).

Although the church groups fall into Walker’s occupational category, they fit into his non-occupational category as well. Most non-occupational interest groups are public interest groups, whose members are motivated by their goal of implementing their definition of the public good, whether it be good government, human rights, or environmentalism. Religious interest groups can also be considered public interest groups, whose definition of the public good comes from a spiritual world-view. Religious interest groups are not single-issue groups. Although many Americans associate the Catholic Bishops with their pro-life and traditional marriage positions, the Bishops have also taken strong stands on nuclear disarmament, human rights, immigration, the death penalty and welfare. While their views are inconsistent with traditional definitions of liberal and conservative, the Bishops maintain that their spiritual worldview informs their position on any particular issue, in what Joseph Cardinal Bernadin termed the seamless garment of life. The Catholic interest groups, unlike many public interest groups, are not mass-based organizations. In this way, the Catholic groups also differ from the Christian Coalition, which in the 1980s purposely set out to recruit members and rally grass roots support for conservative causes. Arguably, the Christian Coalition is also a top down organization, but the Catholic Bishops are less likely to use their grassroots in the same way, for example, by promising to deliver voting blocs (although one could argue such a tactic was used in health care reform).

In fact, the Catholic bishops might not even consider themselves an interest group at all. According to Auxiliary Bishop John H. Ricard of Baltimore, who chaired the Bishops’ Committee on Domestic Policy in 1995:

We lead a community of faith, not an interest group. Our focus is the life and dignity of poor children, not partisan or ideological agendas. We share the values of many reformers and concerns about costs, but worry about human consequences for poor children of some proposals.

Although the bishops are, by political science definitions, an interest group, in that they seek to influence public policy, Bishop Ricard’s point is well-taken: the bishops do not see themselves as leaders of an organized interest group of Catholics, but rather leaders of a religious flock. As the Jesuit theologian Tom Massaro notes, “religious lobbying efforts are really quite different from corporate or industry lobbying efforts” [

16].

According to Jeffrey Berry, a public interest group is a group which “seeks a collective good which will not materially benefit only the members or activists” [

17]. Thus, interest groups which lobby for environmental cleanups will create a benefit that other members of society can enjoy. In like manner, religious groups believe that all of society will benefit from policies that reflect their religious principles. Of course, no group is completely altruistic, and policies that reflect the greater good also may provide some material benefits, when, for example, government funding goes to religious-based charitable organizations. (Sixty-five percent of Catholic Charities’ budget comes from government sources.) In examining state and local government interest groups, Donald Haider made a distinction between spatial interests and functional interests. A group has a spatial interest in determining exactly who will implement policies (in the government groups’ case, whether it is the federal, state or local government which will actually run a particular program). A group can also have a functional interest in a particular policy. The group in this case is more interested in the policy itself than in who actually administers it. While most public interest groups are primarily concerned with their functional interests, Haider argues that government groups are more concerned with spatial interests [

18]. The Catholic groups, as providers of services (education, health care and welfare), also have a spatial interest in addition to their functional interests. Many of the policies for which these groups lobby involve services that they provide. It is often difficult to separate the spatial from the functional interests, and religious groups may have particular difficulty, in that they believe that both society at large and religious institutions have an obligation to provide charity.

In Catholic theology, the concept of subsidiarity comes into play here [

19]. According to this principle, it is incumbent upon society to nurture basic human relationships, and thus policies should be administered whenever possible at the level closest to the individual. Family should have preference over government, local government over state, state over federal. At the same time, however, the more removed levels of government should provide assistance to the smaller forms of community. Former Senator Rick Santorum, a Roman Catholic from Pennsylvania, complained in 1995 that the bishop’s opposition to welfare reform was inconsistent with the concept of subsidiarity, since the reform gives welfare back to the states [

20]. However, the principle may be more complex:

the more extensive or larger forms of community...should not replace or absorb those that are smaller but rather should provide help (subsidium) to them when they are unable or unwilling to make their own proper contribution to the public good.

This principle assumes, of course, that the larger forms of community will have enough resources to provide that subsidium.

In fact, the underlying assumption of the Catholic social tradition has been that the economy, at least in affluent societies, will generate enough of a surplus to ensure the provision of a decent minimum wage for all who are truly needy. It has been inclined to see the reluctance of developed societies to provide benefits as a failure of political and moral will.

The goal of Catholic organizations then, is to ensure that both the Church and the state pursue their moral obligations to the poor. Subsidiarity means that Catholic lobbyists will be interested in both spatial and functional interests.

The Catholic interest groups are a hybrid of occupational and public interest groups. They are private in the sense that membership is not open, but they are public in their goals and world view. In addition, they are different from other public interest groups in that their world view comes from a religious basis rather than personal preference or ideology. They may be different from some other religious groups as well: they are not grass roots organizations. Perhaps religious groups should have their own separate interest group category, which would contain subcategories as well. Religious groups may be institutional/hierarchical, representing the church hierarchy (the Catholic bishops); they may be service-based occupational, representing religious-based service providers (Catholic Charities, Network and the Catholic Health Association); or they may be grass-roots membership, representing church members (the Christian Coalition). In all cases, they would have a public interest component.

3.2. Formation

Another way in which political scientists study interest groups is to examine how and why they are formed. There are two major theories in the literature: the disturbance theory and the exchange theory. According to David Truman’s disturbance theory, interest groups are formed when an economic or political disturbance necessitates their formation [

22]. Alternatively, Robert Salisbury posits that interest groups are formed when an entrepreneur makes a connection between material benefits and group membership. Individuals “exchange” membership for benefits. The only problem with this exchange is the existence of “free riders”, who let other people join the group and reap the legislative benefits without the costs. According to Mancur Olson, the only way to alleviate the free rider is to make benefits “selective”, that is, only available to members [

23,

24,

25].

The formation of Catholic interest groups appears to be relatively straightforward: the Conference of Bishops is a pre-existing group that simply formed itself as an interest group. The question, however, is when and why did the bishops formulate themselves as an interest group? The same question can be asked about Catholic Charities. Interestingly, Catholic Charities constituted themselves as interest groups at the turn of the twentieth century at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, a time when American Catholicism was overburdened with the needs of its burgeoning membership, increasing with each new wave of immigrants from Europe [

26,

27]. The immigrants, largely Catholic and poor, were stretching the abilities of state and private charities to care for them. As Protestant groups attempted to tie aid to conversion, the Catholic hierarchy claimed its own by instituting a vast network of charities, schools and hospitals to care for the immigrant Catholic population, often with aid from state governments [

28]. When these funds became threatened, Catholic Charities formed its own interest group. Thus, an economic disturbance (both the influx of impoverished immigrant Catholics and the resulting struggle over government funding) did, in fact, impact the formation of Catholics as an interest group. Years later, during the Great Depression, Catholic Charities solidified its position by its involvement with the creation of New Deal Legislation. The group also involved itself in the provision of Great Society programs [

29].

The bishops’ lobbying organization traces its roots to a similar time period. Around the first World War, the Catholic bishops established the National Catholic Welfare Conference, which was renamed the U.S. Catholic Conference after Vatican II, when the Pope called for more activism on the part of the bishops, and also gave them more leeway in policy determination [

1]. Two documents from Vatican II,

The Church in the Modern World and

The Declaration of Religious Freedom make clear that the church is expected to engage with society on moral questions and also to provide public explanations for its social teachings [

8]. The Catholic bishops, like Catholic Charities, formed in response to economic, political and religious disturbances. Likewise, Network, the coalition of Catholic nuns who were pivotal in the passage of health care reform, formed in response to the social upheavals in the 1960s and 1970s, and specifically in response to the Vatican II call for social justice. “Women religious boldly joined in the waves of civil rights, feminist and anti-war activism that were sweeping the U.S. During their weekend meeting [on 17 December 1971], they voted to form a national ‘network’ of Sisters to lobby for federal policies and legislation that promote economic and social justice” [

30].

Catholics at the beginning of the twentieth century had to deal with anti-Catholic bias, and, according to John Coleman, reacted in two ways, each of which affected their interest group activities. The first way was for Catholics to create and retreat into their own society. If they faced discrimination and Protestant prayers in public schools, they would set up their own, Catholic, school system. If the intent of Progressive social workers included conversion of Catholic immigrants to a more acceptable Protestantism, then Catholics would establish their own charitable societies. This first path paved the way for the creation of a Catholic system of social services that eventually found voice in Catholic Charities, U.S. Ironically, although the various Catholic schools and charities were set up as something of an escape from the outside (Protestant) world, throughout their history they have been involved in lobbying the government. The second path that American Catholics chose was to participate in society, and engage in debates about the proper role of government and society. In order to have their voices heard, however, the groups needed to present a universal message, based on broader ideals rather than papal authority.

Instead, they linked up to a more universalistic heritage of human rights, the dignity of the person. The very anti-Catholic biases, so strong in America in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, forced the church to make its appeals to public policy in a public, rather than a sectarian language. Otherwise, it would not gain a hearing [

8].

Thus, on two fronts, Catholics at the turn of the last century set the stage for participating in the political process as interest groups. First, they formed their own charitable organizations and consequent interest group, and second, they learned to debate in the public arena in universally accepted moral language.

As elite, rather than grassroots, groups, the Catholic interest groups do not face the “free rider” constraint posited by Mancur Olson. Interest groups made up of professionals or elites do, however, form around the material interests of their members. In this respect, the Catholic Bishops, the Catholic Health Association and Catholic Charities are no different from other such groups. On issues such as school vouchers, health insurance and public funding of private charities, the Catholic Church and its organizations would obviously benefit materially from particular government actions. As with any religious group, however, it is difficult to tease out the material from spiritual benefits. It is overly cynical to believe that religious interest groups lobby with the sole purpose of directing money to themselves, although it would also be overly simplistic to state that religious groups act only out of altruism for the poor or downtrodden. However, the spiritual dimension of religious groups does have an impact on both their lobbying efforts and their ability to avoid the free rider effect. Religious interest groups such as the bishops lobby for policies that are consistent with a particular world view that goes beyond mere public interest and enters into the realm of morality. As groups that are proposing what is both morally and spiritually (as well as, in some ways, economically) rewarding, religious interest groups can attract membership with the carrot of spiritual benefits, which are for some a more powerful force than material benefits.

3.3. Group Resources

Any interest group relies on its own resources to make its voice heard in the policy process. A group’s resources may include its membership, its staff, its expertise, its leadership and its access to decision-makers.

3.3.1. Membership

As discussed earlier, the membership of USCCB is the bishops and cardinals of the United States. Membership as a resource is useful in terms of expertise (in the case of Catholic Charities, the Catholic Health Association and Network) and moral authority (USCCB). The Catholic interest groups, because they are not grassroots organizations, tend to rely less on their membership to communicate their views and more on the leadership and lobbyists. There are those who believe that the Catholics should learn from the Christian coalition and make more use of their large population to influence policy. After all, the Catholic Church is the largest single denomination in the United States. There are several problems with this approach. First, the views of the Catholic Bishops are by no means synonymous with the views of the majority of Catholics on a variety of issues, from birth control and abortion to gay marriage. Second, the Catholic Church is loath to create a voting bloc, in part because it believes (with good reason) that no candidate or party represents the Catholic Bishops’ views on the continuum of issues (neither party is both pro-life and anti-death penalty, for example). Third, as 501(c)3 non-profit organizations, the Catholic groups are prohibited from endorsing candidates, and limited in their lobbying efforts. Fourth, the bishops do not view themselves as spokespersons for the public opinion of their church members but rather as moral leaders for their church and others. As a lobbyist for the bishops put it:

The bishops speak to the people of the church, not for the people of the church. The bishops really view themselves as teachers. They are not delivering a voting bloc, they are articulating moral meaning. There are implications to that.

While the greatest strength of the Catholic organizations, particularly the Bishops, may be their ability to articulate moral positions, their greatest weakness as lobbyists is their lack of a voting bloc and their relatively weak grassroots structure. This is not an oversight—the bishops are aware that they represent “a large church with a large agenda, and it is impossible to find one candidate, one party to represent us” [

32]. According to John Ricard, auxiliary bishop of Baltimore, “We are teachers. Our message is not partisan, it’s moral....people of good will can come to different conclusions [although the bishops should help inform their consciences]” [

33]. The bishops are more interested in guiding and educating their flock, useful tools in their trade, but tools which do not always translate well into political currency.

3.3.2. Staff

The professional staff of the Catholic organizations is located in or near Washington, DC. The USCCB has professional lobbyists and a government liaison office. In addition, the lobbyists can call upon the resources of any of a large number of departments which conduct research in areas from international justice and peace to migration and refugee services ([

6], p. 26). Catholic Charities U.S. has several lobbyists working out of their Alexandria, Virginia, offices. The Catholic Health Association (CHA) and Network also have staff in Washington, DC. devoted to lobbying.

3.3.3. Expertise

Expertise is the chief resource of the Catholic organizations providing direct services. The Catholic Health Association, which is an umbrella organization representing Catholic health care providers including hospitals, can speak to the implications and ramifications of providing health care or increasing the numbers of insured. Catholic Charities USA, which provides relief services domestically, is, in fact, the largest private provider of non-health related social services in the United States. Both groups, as well as the Catholic bishops, are also involved in the public policy process, bringing their experiences to bear in their lobbying efforts. In addition, the bishops take credit for the work of the Catholic organizations. For example, during the health care debate, Bishop William Murphy talked about “his” hospitals: the Catholic hospitals in his diocese in Long Island [

34]. According to Allen D. Hertzke, who studied the role of religious groups in the lobbying process:

Liberal lobbies, whether Catholic or Protestant, find their greatest success when they report on the homeless shelters, soup kitchens and the work of their social service agencies with the poor and those of modest means.

However, expertise goes beyond experience in the field. The U.S. Catholic Conference uses its research departments to examine the theological implications of any number of issues and is the envy of some Protestant groups in its ability to produce documentation and theological background on important moral issues [

1].

The expertise of the Catholic groups is a little different from expertise as usually defined for interest groups. It goes beyond mere knowledge or information and has a moral weight. Religious interest groups have somewhat of a luxury in that they can frame their arguments in a moral and spiritual context, and sometimes this is exactly what the public and policymakers want. In fact, a congressional staffer in 1997 told one of us that she wished the bishops and other religious groups (Jewish and mainline Protestant organizations) had come out more strongly in opposition to welfare. Although a staffer for one of the Catholic groups questioned how they could have been stronger in their statements, the point remained that policymakers wished for a moral statement on the issue, understanding that it could be a powerful public opinion tool. In addition, staffers were concerned about the moral implications of the opponents to welfare reform.

The Catholic Bishops use—or attempt to use—their moral leadership in developing policy statements and drawing attention to particular issues. The bishops’ strongest asset is their ability to provide moral authority on issues of conscience, to Catholics and non-Catholics alike. Although the USCCB is not a grassroots organization, most Catholics are aware of its general positions on issues, more so than Protestants are aware of their denominations’ issues stances. In the case of health care reform, the Bishops made those positions known through bulletin inserts that went to all parishes in the country.This is not to say that Catholics are always aware of specifics related to legislation, or even that they agree with the bishops’ statements. Nonetheless, the bishops’ statements provide a focal point, as well as a basis for discussion. In welfare reform, for example, the USCCB released a statement of Moral Principles and Priorities in November of 1995. That statement set out the bishops’ concerns, and was intended to be “foundational policy” or “principles by which welfare policy should be evaluated”(interview with Patricia King). It is important to note that moral leadership in the eyes of the bishops involves teaching rather than exhorting to vote, and that the reliance on lofty moral principles is sometimes at odds with the give and take and compromise necessary for passing legislation.

3.3.4. Access

No lobbying group can be successful unless it can make its voice heard. While the bishops can garner media attention by their policy statements, policymaking also requires the ability to influence decision-makers at a more personal level. Access refers to the ability of interest groups to get their foot in the door: to meet with congressional staff and/or Members of Congress. If a group has no access, it has no voice. Like other interest groups, the access of the bishops varies from policy to policy, from lobbyist to lobbyist and from office to office. In general, the bishops’ lobbyists don’t have a difficult time meeting with staff of Members of Congress. Access may be particularly easy to Catholic Members who are sympathetic with their causes, or Members who represent a large Catholic constituency. In addition, their expertise serves the Catholic groups well in gaining access to all congressional offices. Hertzke notes that the quality of information provided by lobbies is critical to their success in gaining access to congressional offices. In this regard, the United States Catholic Conference appears particularly adept [

1].

As an entity, the Bishops are generally well, although not universally, known. Indeed, according to one lobbyist, the high turnover rate of the 1994 Congress, when the Republicans gained the majority, meant that there were larger numbers of staff people who had never heard of the Catholic conference [

31] making access more difficult.

3.4. Techniques

3.4.1. Inside versus Outsider Strategies

Interest groups rely on a variety of techniques to get their voices heard in the policy process. The choice of techniques depends on the issue and the resources that the interest group possesses. Groups may choose between “direct” or “indirect” techniques, either communicating directly to policymakers or using media or grassroots to communicate [

17]. Often groups will use a variety of techniques packaged in either an “insider” or an “outsider” strategy. Inside strategies rely on access to decision-makers and include the provision of information through testimony, direct contact with staff or Members of Congress and sometimes drafting of legislative language. While inside strategies are likely to be used when there is little conflict on a piece of legislation, outside strategies require mobilization of membership and grass roots lobbying, and are often used on controversial legislation [

35]. Interest groups exhort their members to write letters, and may stage demonstrations or other activities to garner media attention. Outside strategies are used by groups whose main resource lies in their large membership.

Catholic interest groups are more likely to rely on insider strategies, which make use of their group resources. Information is one of the strengths of both the USCCB and other Catholic lobbies, and insider strategies allow the groups to get their information across. Lobbyists make a point to meet with congressional offices and are often asked to testify on issues. On some issues, the USCCB will identify particular Members of Congress and request that the Cardinal or Bishop from their district contact them.

No group relies on a single strategy, and the Catholic groups also supplement their insider tactics with some outsider strategies as well. For example, individual bishops may choose to write editorials in local or national newspapers, drawing media attention to an issue. Although their grassroots organization is not as easily mobilized as some other lobbying organizations, the Catholic groups do use networks to notify individuals at the diocesan and parish levels of governmental actions, and encourage them to write or call congressional actors. During the health care debate in 2009–2010, the bishops sent bulletin inserts to be distributed in Catholic churches throughout the United States.

One of the greatest skills in legislative policymaking is the ability to compromise. Compromise is the lifeblood of politics; without it, very little legislation would get passed. Religious interest groups are at their weakest in the area of compromise, because much of what they do is based on moral principles which are the very antithesis of compromise. The philosophical basis of religious lobbyists can become a “psychological impediment” to “strategic thinking and compromise” [

1]. The business of religion is in defining right and wrong, should and shouldn’t, and although most religions will admit to gray areas, the emphasis on absolute moral principles means that religious groups will have difficulty in the legislative arena, where there are no absolutes. As a Presbyterian lobbyist put it, “I don’t try to evaluate effectiveness. I am more concerned with the biblical basis on which I stand” ([

1], p. 75). As we shall see, moral principles made it difficult for the bishops to compromise on health care reform, just as it was difficult for any number of liberal interest groups to compromise in welfare reform. In addition, it is often difficult to move from philosophical or theoretical perspectives to more pragmatic issues, which may require short term action and compromises on details.

Urgency is not one of the defining features of Catholic social teaching, which has been maturing for over 100 years now and characteristically prefers long-term perspectives and universal views. It is not a ready source of sound bites for the politicians of the electronic age, and it cultivates its own terminology, a style that is often ponderous and opaque and a stance that sets out to instruct and exhort rather than to promote and persuade [

21].

3.4.2. Coalitions and Issue Networks

Interest groups often form coalitions with one another in order to present a united front on a given issue. Coalitions are useful to both interest groups and decision-makers. They allow for compromises to be made outside of government, they encourage the exchange of information and they broaden the groups’ focus [

22]. Coalitions are alliances of groups that enable them to broaden their base and increase their bargaining position. Coalitions often form around specific issues, and are generally temporary in nature. “Coalitions are ‘action sets’, temporary alliances for limited purposes” [

36]. Indeed, Hugh Heclo’s concept of “issue networks” posits that interest group alliances are fluid and vary from issue to issue [

37].

Religious groups find coalitions useful. For the Catholic interest groups in particular, however, coalition building can involve vastly different actors, depending on the issue. The Catholic interest groups flow in and out of several, sometimes conflicting, issue networks. On abortion-related issues, the Catholic groups align themselves with other pro-life interest groups, notably the Christian right. On poverty and welfare issues, however, Catholic interest groups are likely to be in alignment with more liberal interest groups, who might oppose them on other issues. Thus, for example, the Catholic bishops, who would be working against the National Organization for Women on legislation dealing with abortion, actually worked with the organization in softening the family cap provisions in the welfare bill. As a USCC staff lobbyist put it.

We are in a coalition with religious groups about debt relief, and religious freedom. We work with American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) on debt relief but not international relief. On life issues, we work with anti-abortion groups, on violence against women, we work with the National Organization for Women (NOW). There’s a fine line on how you work with these groups. As a lobbyist, I’m not responsible for life issues. I can talk to folks at NOW about my issues.

One of the most interesting aspects of the Catholic interest groups is the inability to place them predictably into a liberal or conservative category.

Poised both theologically and (perhaps) strategically between the two poles of Protestantism are the Catholic Bishops and the evangelicals. The increasingly assertive U.S. Catholic Bishops confound conventional notions of liberal and conservative by simultaneously opposing abortion and taking liberal positions on nuclear arms and welfare-state spending.

Although the Catholic positions on these issues are inconsistent with current definitions of liberal and conservative, they are based on an internal consistency that has been described by Joseph Cardinal Bernadin as a “seamless garment” approach, in which life is valued in all forms and at all stages. According to this approach, a pro-life, anti-death penalty, pro-welfare, pro-traditional marriage ethic is internally consistent. Coalition-building then becomes difficult, because such positions are not consistent with the views of external groups. The bishops, however, are comfortable with the external inconsistencies. Their interest lies in teaching and articulating moral precepts, and they are less concerned with political alliances. In fact, even when the bishops agree with outside interest groups, they are hesitant to sign joint statements, preferring to express not only their position, but the moral reasoning behind it (and the moral reasoning is sometimes at odds with the reasoning behind other groups’ support of an issue). “The bishops are independent. The basis of their actions differs from other groups, even if the bottom line is the same. They would rather write their own letters and articulate the basis of their decisions” [

32].

3.4.3. Impact

It is difficult to measure the success or failure of an interest group on any particular policy. One can examine the policy statements made by a group, and compare them to the provisions of final legislation or one can ask interest group and congressional actors to identify who had an impact on what provisions. Neither method is completely satisfactory. An issue a group claims as a success—and that is consistent with their policy positions at the beginning of the process—may have been resolved in the same manner even without the group’s input. Nonetheless, an in-depth analysis of a particular policy, along with a general knowledge of resources, techniques and other factors that are more likely to lead to success, can demonstrate whether and to what extent a group had impact on a particular policy. In general, interest groups are more successful on incremental rather than comprehensive change [

38], narrow issues over broad, non-controversial over conflictual changes, and keeping the status quo rather than changing it. In addition, interest groups are more successful when they act in coalitions, and when they have access to decision-makers.

Let us now examine how the US Bishops (along with other interest groups) fared when lobbying for welfare reform in 1996 and health care in 2010.

Both of these policies were proposed by Democratic presidents and both involve areas in which Catholic interest groups have historically been involved. In welfare, the policy was a retrenchment of decades of an entitlement to welfare benefits, as a compromise between the Democratic president and Republican Congress. The bishops, along with other liberal interest groups fought against the conservative reform. Health care policy, on the other hand, was a broad-based comprehensive reform, bringing care to millions of individuals. This was a policy the bishops had been promoting for years, and with Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress it seemed that policy agreement was inevitable. The sticking point in this case was whether the federal government should pay for abortion services and how to define what constituted such payment.

6. The Catholic Bishops and Health Care Reform

When Barack Obama was elected President in 2008, the path was paved for health care reform that would include universal insurance coverage for all Americans. This was an issue that the Catholic Bishops, along with other interest groups, had been supporting for decades. Whereas in welfare reform, the bishops were opposed to the general premise of the legislation (ending the entitlement to welfare), in health care, the bishops’ opposition was over a single issue: abortion. The bishops, along with other pro-life groups, wanted to ensure that any health care reform bill would adhere to the decades-old Hyde amendment, which prohibited federal funding of abortions.

2In October of 2009, as the health care debate was heating up, the bishops released a statement outlining their main objectives for the legislation:

- (1)

Government should not pay for abortions nor mandate that health care workers participate in abortions.

- (2)

The poor and vulnerable should receive health care coverage.

- (3)

All immigrants, including those in the country illegally, should be included in any expansion of health care coverage [

56].

Clearly, this was the bishops’ moment. They could have a hand in ensuring expansive health care reform and were quite hopeful that they could exclude abortion coverage from new government-run insurance, or at least maintain the status quo.

6.1. The “Status Quo” on Abortion Coverage

What was the status quo on abortion? It depends on whom you ask. Pro-life groups, such as the Catholic bishops, looked to the Hyde amendment. Historically, pro-lifers had been successful in keeping federal funds from paying for abortions. In the Medicaid program (health care for the poor), the federal government is prohibited from paying for abortions, though states may use their own funds to expand Medicaid coverage to include abortion. Seventeen states provide their own money to cover abortions under Medicaid. In addition, Tricare (health insurance for military personnel) and the 250 insurance plans for federal employees are expressly prohibited from covering abortions in most cases [

57]. Thus, the bishops’ position was that the status quo on abortion would mean no federal funds being directed to pay for abortions.

According to pro-choice advocates, including the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL) and NOW, the issue was not so straightforward. A comprehensive government health care plan would replace the private policies that some women currently had. In addition, some of these policies were covering abortion services. If the health care legislation were to move a woman from a private health plan that covers abortion to a public health plan that does not, then she would lose abortion benefits. For the pro-choice lobby, the status quo meant that women who have abortion coverage would continue to have it. How many women might lose abortion coverage by moving from private to public plans was an open question, as was the number of women who might be likely to take advantage of such coverage. (According to the Guttmacher Institute, 87% of private insurance policies covered abortion, leaving 47% of insured workers with abortion coverage. In addition, according to the Guttmacher Institute study from 2003, only 13% of women receiving abortions file for insurance claims [

58,

59]. Finally, pro-choice groups also argued that if government-funded plans prohibited abortion coverage, then private insurance companies would have little incentive to provide such coverage, further limiting women’s access to abortion [

57].

As health care legislation wended its way through the House and Senate, a tentative compromise was reached: every state health care exchange would be required to provide at least one plan that included abortion coverage, and one that did not. Further, the plans that included coverage would be required to strictly segregate funds such that abortions would only be paid for through premiums or co-pays, not through federal subsidies. This compromise was present in the Baucus plan in the Senate (the “chairman’s mark”) and in the House plan as a result of an amendment proposed by Lois Capps [

57,

60]. The compromise was strongly opposed by the USCBB. Cardinal Justin Rigali, Archbishop of Philadelphia and chairman of the USCCB’s pro-life committee, initially expressed support for the health care plans being considered in Congress. By August, however, in response to the abortion compromise, he sent a letter to Congress requesting that the health care bill maintain the abortion status quo. As the legislation stood, according to Rigali, the protections against abortion were not strong enough, and the bishops could not support it [

61].

This put President Obama in a precarious situation. He counted on the support of the bishops, if only to ensure that pro-life Democrats would vote for the package. Beyond that, the bishops were, in fact, a powerful ally. They represent the largest religious group in America, comprising approximately 20% of the total population [

62,

63]. They also are responsible for the 620 Catholic Hospitals in the United States, and, as such, are providers for a large swath of health care in the U.S. (and would also stand to materially benefit from increased insurance coverage). Not only do the bishops represent a large constituency, but their support would also lend a moral logic for health care reform. The Catholic bishops also differed from Protestant evangelicals, who were opposed to the underlying principle of health care reform: that the government should pay for the health care of its citizens [

64]. The President went on the offensive, starting with a conference call in August 2009, which was podcast to 140,000 religious leaders. The call was organized by the Faith for Health coalition, a group including Buddhists, Protestants, Catholics, Muslims, and Jews, organized to help religious leaders inform and mobilize their congregations [

65,

66]. The President reassured them that no federal money would be used to pay for abortions [

60]. He continued on this theme in September, saying “and one more misunderstanding I want to clear up: Under our plan, no federal dollars will be used to fund abortion and federal conscience laws will remain in place” [

67].

6.2. The Bishops Win a Battle

By late fall 2009, it was clear that health care reform legislation was likely to pass. The House was moving faster than the Senate. In both chambers, Republicans were opposed to the legislation on principle (big government) and for political reasons (they were loath to give the president a win), so the Democratic leadership needed to make compromises within its own party. In the House of Representatives, all looked like smooth sailing, until Speaker Nancy Pelosi was faced with the defection of 40 or so pro-life Democrats. Their leader, and chair of the pro-life caucus, was Rep. Bart Stupak (D-PA), who had introduced a pro-life amendment in the Energy and Commerce Committee. It had failed by one vote [

68]. In late September, 31 House Democrats sent a letter to Speaker Pelosi asking for a floor vote on that same amendment. Rep. Stupak said he had the votes of 40 Democrats—enough to derail health care legislation over the abortion issue. Pelosi was worried about appeasing her pro-choice allies. President Obama himself telephoned Stupak, and asked him to work it out within the party. Pelosi then called Stupak in to meet with her [

69]. Abortion restrictions were back on the table, and Pelosi faced a tough battle, negotiating between groups like NARAL, who were fearful of losing any ground on abortion, and the USCCB, which was adamant that (1) government not pay for abortion, and (2) “segregating” federal subsidies from premiums was insufficient.

One possible compromise, the Ellsworth amendment, was to have a private contractor ensure that no federal funds directly subsidized abortion. This was good enough for some pro-life Democrats, but not for the USCCB, Bart Stupak or his allies. They felt that the legislation would still

indirectly subsidize abortions, and further, would encourage more abortions [

70,

71,

72]. Obviously, the pro-choice groups disagreed on the former point, and were not unhappy with the latter, preferring to expand, rather than limit access to abortion.

The floor vote was scheduled for the evening of Saturday, 7 November, but the abortion issue was still unresolved. Pelosi needed to get all 218 votes from within her Democratic party, and given the Democratic majority of 258, there was a margin of 40 votes, just enough for the pro-life forces to stop the bill. Obama went to Capitol Hill to rally the troops and urge a yes vote on the legislation. Negotiations went through the day and into the evening. An early deal brokered on Friday had to be called off, when Pelosi realized “I can’t hold my side together” [

73]. Pelosi met with Stupak and other pro-life Democrats, as well as representatives from the USCBB, which had inserted a pamphlet into church bulletins the week before, encouraging the faithful to oppose health care reform unless the abortion issue was resolved favorably. Stupak’s amendment proposed banning all spending on abortions: in both the government-run insurance that was part of the plan, and in the private insurance policies that would be available in the state exchanges [

74,

75].

In the end, Pelosi decided to allow the Stupak amendment to come up for a vote. It won, and Stupak delivered his 40 pro-life votes to move health care to final passage in the House. Abortion rights advocates were furious.

The bishops emerged victorious in this battle over abortion, as numerous contemporary newspaper accounts attest:

Advocates on both sides are calling the vote Saturday the biggest turning point in the abortion battle since the passage of a ban on what opponents call partial-birth abortion 6 years ago....The bishops’ role was pivotal in part because, based on their past advocacy, many Democrats expected the bishops to be a crucial ally in the push for universal health care.

The Catholic bishops have emerged as perhaps the most influential religious group on this issue. Especially since the 1960s, they have advocated that the health care system in the United States should be extended to everyone, regardless of their ability to pay. And unlike conservative Protestant groups, Catholics are generally not opposed to the federal government ensuring universal health care...the bishops were largely credited with a lobbying effort that resulted in an amendment forbidding the use of federal funds for insurance cover of abortion.

Emboldened by their success in inserting restrictive abortion language into the House health care bill, Roman Catholic bishops say they’ve found a lobbying model that could provide them a louder voice in future policy debates.

Though large organizations such as the American Association of Retired Person (AARP) and the American Medical Association (AMA) backed the bill, the most important group at the end may have been the USCCB, which wanted a longstanding ban on federally funded abortion maintained.

There was, however, a lone voice crying out in the wilderness. Mike Doyle, a pro-life Democrat from Pennsylvania was not so certain that the bill’s passage was anything more than a pyrrhic victory. After all, the Senate version hadn’t passed, and would likely be significantly different from the House bills. The two bills would have to be merged into one, presumably by conference committee action. Doyle wondered aloud if this were a victory that would be overturned in the coming weeks:

It’s pretty clear that this could be a shell game that’s under way. [The amendment] could pass here in the House making sure this bill passes. But when it comes back in conference, we have no guarantee that the language will remain .

Doyle was definitely right about one thing: There were no guarantees in health care reform.

6.3. But Ultimately Lose the War

Once the House finished its work, attention turned to the Senate, where the bishops were much less visible or successful. Without too much fanfare, the Senate rejected a restrictive abortion amendment, in a 54–49 vote, despite “an intense lobbying campaign” from the bishops and Evangelical Protestants [

78,

79]. The Senate bill differed in other ways from the House bill, though no other issue was so important to the Catholic bishops and pro-life lobby. The next step would be a conference committee to resolve the differences between the House and Senate bills. Pro-life House Democrats were preparing to negotiate to keep the Stupak amendment in the final bill.

On 19 January 2010, a bomb dropped:

The Senate lost its “filibuster-proof” 60-vote majority when Republican Scott Brown won a special election in Massachusetts, filling the seat that had been held by Democratic Senator Ted Kennedy for more than 30 years. The Senate Democrats no longer had sufficient votes to pass the bill—any bill—that would come out of conference committee. Health care reform looked dead in the water.

Democrats from the House and Senate met with administration officials and Obama in the White House to plan their next moves. The conference committee was abandoned, and there was talk of trying a less comprehensive approach. However, Pelosi and Emmanuel favored a trickier, two-step strategy. They decided to have the House vote on the Senate version of the bill as is and then include House changes to the bill in a reconciliation bill—which, under Senate rules, could not be filibustered and only needed a majority (50 percent plus one, or 51 votes) to pass. (Convincing House Democrats of the efficacy of this two-step strategy was not an easy thing to do, given that the House considers the Senate to be “a graveyard for hundreds of pieces of House passed legislation” [

80]. To the bishops’ dismay, this strategy left the less-restrictive Senate abortion language intact. The Senate language specified that no public funds be used for abortion, and included the segregation of government funds (which could not pay for abortions) from private premium payments (which could). It also included a stipulation that everyone who signs up for a plan that includes abortion coverage (and state exchanges would be required to offer one that does not) would make two premium payments: one for the insurance generally, and one for the portion of the insurance paying for abortion coverage.

Neither pro-life nor pro-choice groups were happy, and the bishops and pro-life Democrats vowed to continue the fight to include the Stupak amendment in the House. “The fact that the pro-abortion groups don’t like it either doesn’t make me support it”, said Richard Doerflinger, spokesman for the USCCB [

81]. This time, Pelosi wouldn’t budge. The Senate bill would be voted on as is, and the abortion language could not be included in the reconciliation bill.

It was a tense few days in the House, as the President and Democratic leadership lobbied to convince members of their own party to vote for the bill. Not everyone was opposed on the grounds of the abortion language. Some opposed the bill because it was too expansive, or not expansive enough. However, the 40 pro-life Democrats seemed to hold the legislation in their hands. Either they—with the bishops—could convince leadership to restrict abortions, or they could force the bill to die. For their part, the bishops engaged in intense lobbying, emboldened by their success in November.

Then, the Democratic pro-life coalition began to crumble. First, the Catholic Health Association said that it could live with the Senate language. Then Network, an umbrella group of women’s religious orders representing 59,000 nuns, said that the pro-life stance was to vote in favor of health care reform. Now, Catholics could point to not one, but two Catholic groups other than USCCB to defend their votes for the bill. As Linda Feldmann noted in the Christian Science Monitor, “The one-two punch represents an extraordinary display of dissent against the USCCB...Pro-life Democrats are starting to peel off and say they’ll vote for Obamacare” [

82].

Suddenly, pro-life Catholic Democrats who truly wanted health care reform had political cover: Catholic hospitals and the nuns supported it, saying expanded health care coverage would save lives, making up for the bill’s less-than-perfect abortion restrictions. The bishops had been outflanked. The importance of the nuns cannot be overstated. A group of 60 nuns representing Network had sent a letter to 18 Catholic members of Congress, urging them to vote for the bill as a “faith mandate”. They argued that the benefits of the bill in providing health care services to poor women and children outweighed its negatives in expanding abortion coverage. They did not see the abortion compromise through the same lens of moral absolutism that the bishops did; they used their position as workers in the trenches to defend their position; and they provided a moral rationale for a yes vote on health care. In the process, they also undermined the authority of the bishops, theoretically their superiors.

Two prominent pro-life Catholics, Dale Kildee (D-MI) and Charlie Wilson (D-OH), announced that they would vote for the bill. Dale Kildee had been a Jesuit seminarian, and in announcing his support, he spoke of his own discernment and consultation with his priest:

I have always respected and cherished the sanctity of human life. I spent six years studying to be a priest and was willing to devote my life to God. I have listened carefully to both sides of the debate, sought counsel from my priest, advice from family, friends and constituents, and I have read the Senate abortion language more than a dozen times. I am convinced that the Senate language maintains the Hyde amendment, which states that no federal money can be used for abortion.

With this, Kildee laid out a pro-life, Catholic rationale for a yes vote on health care reform, backed by the support of the nuns, rather than the bishops. Kildee’s position seems to resonate with American Catholics who have been raised in an individualistic culture and encouraged to think for themselves. Kildee placed these American values within the Catholic tradition of discernment and reliance on one’s conscience. In so doing, he moved away from a complementary Catholic tradition of respecting authority and hierarchy, and weakened the political position of the bishops. Indirectly, Kildee’s position also elevated the moral authority of the nuns over the moral authority of the bishops, and it points to an ongoing tension between individual conscience and authority.

In any case, Kildee’s vote and statement, along with fellow Catholic pro-lifer Wilson’s vote, paved the way for other Catholic Democrats to declare their support for health care. The “Catholic position” on health care was no longer synonymous with the “bishop’s position”:

In the past, the bishops’ word on such questions was considered law and rarely challenged by the faithful. But in recent years, Catholics have more frequently challenged their leaders, especially on issues such as birth control and a greater role for women in the church.

Catholics, like other politicians, had competing motives and desires in health care reform. A historic bill looked like it might pass, and many pro-life Catholic Democrats wanted their names associated with it. Party loyalty was also at play here, and any pressures the bishops might put on Catholic politicians were counterbalanced by competing pressures from party leaders and colleagues to support the party and the President. Reelection was also a concern, as a vote against health care reform in a strongly Democratic district might end a representative’s career. Real moral concern about the issue of abortion would also play a part in a Congress Member’s decision, as well as fidelity to his or her church and faith. As with many decisions made by Members of Congress, the vote for health care reform involved a complex and competing set of motives, objectives and goals. “It’s a very difficult struggle”, according to Tom Massaro. “There’s no formula...for a legislator to vote up or down based on a simple, cookie-cutter determination” [

85].

On the left, Kucinich had announced he would vote for the bill as well, and the momentum for passage had begun. One by one, the votes began to inch up to 218. One of the last holdouts was Bart Stupak, author of the compromise abortion amendment in the House bill. He also had a number of pro-life Democrats supporting him, perhaps enough to sink the bill. Stupak was lobbied heavily by Democratic leadership. The White House negotiated a deal with him that the President would sign an executive order specifying that, consistent with the Hyde amendment, federal dollars would not be used to pay for abortions. Stupak was still wavering when Rep. Dingell, the Dean of the House, a pro-life Catholic and a lifelong supporter of nationalized health care, met privately with him in his Capitol hideaway [

86]. The two men had a close relationship, and Dingell managed to convince Stupak to accept the compromise, and the passage of health care reform was sealed. The USCCB remained staunchly opposed; they and other groups felt that the executive order provided insufficient protections against government funding of abortions. Stupak became a pariah in the pro-life movement, and ultimately lost reelection.

On 22 March 2010—without a single Republican vote—the House voted in favor of the Senate health care bill. The bishops had gone from the pivotal group in passage of the initial House legislation, to the sidelines of the debate.

7. Conclusions

How does one assess the bishops approach to policy-formation? Perhaps John Carr captures it best, noting that “Catholic advocacy is more effective at shaping the debate than determining its outcome, raising key moral questions more than providing specific policy answers” [

87].

In both health care reform and welfare reform, the Catholic bishops had the access and resources to be powerful voices in the debate. Decision-makers looked to them for support and expertise. In both cases—but particularly in health care—the bishops were limited by their inability to compromise on moral issues. In health care, the bishops were also undermined by other Catholic interest groups whose support of the legislation allowed fence-sitting pro-life Catholics the opportunity to vote in opposition to the Bishops’ views. This included even the bishops’ staunchest allies in the House.

The Catholic interest groups involvement in welfare demonstrates the conditions under which interest groups are likely to have limited success. In the first place, the access of the Catholic groups, like other liberal interest groups, was somewhat curtailed. Most of the groups had nourished their relationships with Democrats in Congress, who, until 1994, were in control of the welfare reform process. When the Republicans decided to reform welfare, the welfare lobby had limited access to decision-makers. The Catholic groups, in particular, the Bishops, had somewhat more access. A delegation of bishops was able to meet with the welfare architects to discuss the plan. Since the chair of the subcommittee responsible for welfare reform was a Catholic himself, the bishops had an inroad not open to other groups. In addition, perhaps the Catholic groups, known for being conservative on abortion and family issues, had somewhat more credibility in the eyes of Republicans than other welfare interest groups. Democratic Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a lifelong Catholic, praised the role of the Catholic Bishops in welfare reform, singling them out from other liberal interest groups.

Honor on high as well to the Catholic bishops, who admittedly have an easier task with matters of this sort. When principles are at issue, they simply look them up. Too many liberals, alas, simply make them up [

88].

Access does not guarantee success, and a meeting with the important congressional players had no net gain for the bishops. The problem is that politics looks for middle ground, and in this instance, there was none. Republicans wanted to reform welfare their way: give it back to the states and emphasize personal responsibility. They felt that the liberals had had their chance for 60 years, now it was time to do something different. The bishops, for their part, acknowledged that welfare needed changing, but they were adamantly opposed to ending the entitlement on moral grounds. The position of the Catholic interest groups was that the Republican welfare bill should not pass, that the end to the entitlement was quite simply unacceptable, as were the new restrictions on eligibility for immigrants. There was no carrot (and no stick) that the Catholic groups could offer. It was as if both sides dug their heels into the ground. In addition, since the ground was Capitol Hill, and they had the majority, the Republicans got their way. This is not a completely unusual position for religious interest groups to be in. Their orientation is often at odds with the rules and norms of politics.

In interviews with congressional staff members the same theme repeatedly emerges: to be effective, religious lobbyists must learn to play the game, to think strategically and to understand the norms of congressional politics.

The only issue that the Catholic groups even partially won in welfare reform was the family cap. Here, there were two elements in place that are important for interest group impact on legislation: a compromise position and a coalition of groups. The family cap was not eliminated—it was simply made more optional. The groups were able to make some kind of bargain with the Republicans in Congress. In addition, the fact that the coalition of groups included both the pro-life lobby and women’s interest groups was enough to give anyone pause. Diverse groups show widespread support for an issue. It is important to note that this compromise is not really a victory (twenty-three states ended up with the family cap). The fact that the groups claim it as such is testament to how far removed each side was from the other on welfare reform.

Finally, no matter how effective interest groups may be, they have to face political realities. The welfare reform train was pulling out of the station, and there was not much that the groups could do to stop it. In order to have an impact on legislation, interest groups must have allies in the legislative process. In this case, there really were none. The President made it clear that he would sign “just about anything”, and many Democrats in Congress, without cover of a presidential veto, felt they had to vote for reform to ensure reelection [

89]. There was almost a feeling of shell-shock: the Democrats were unable to fathom that they had lost the majority. For their part, Republicans were like the proverbial kid in the candy store, who realized they could do almost anything they wanted. There were compromises on the bill: it cost more than the initial Republican plan, spent more money on child care and maintained the entitlement status of the food stamp program [

90]. However, the compromises were made either between House and Senate Republicans, or with an eye to a possible presidential veto. For some time, it looked like the political calculation of the Republicans was to force a presidential veto to create a campaign issue. All the bishops and other groups could hope for was to soften the bill, and to keep up a conversation about obligations to the poor.

In health care reform, on the other hand, the Catholic Bishops had advantages they had not had in welfare reform: they did have access to Democratic decision makers, many of whom were Catholic. They also had allies in the 40 pro-life Democrats who seemed to hold the fate of the bill in their hands in the House, though most of them eventually abandoned the bishops to vote for the Senate version of the bill. The USCCB also supported the overall premise of the bill, that the federal government should be involved in the provision of healthcare in the United States.

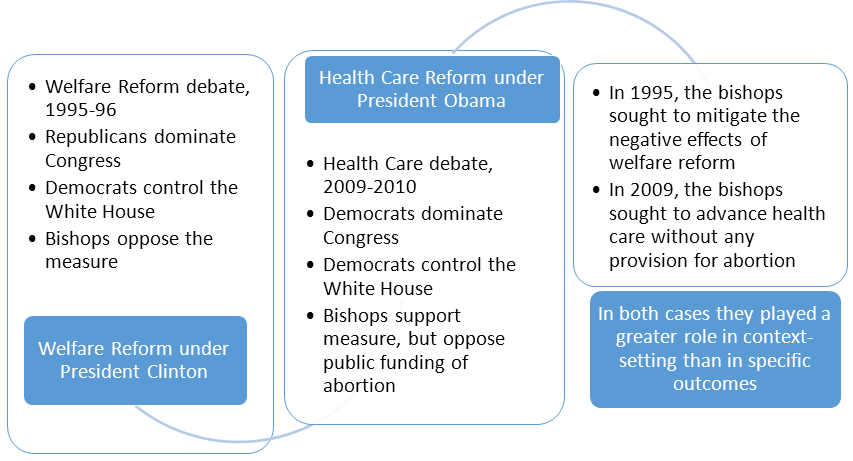

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the atmosphere in health care reform was in some ways the mirror image of the atmosphere in welfare reform:

Figure 1.

The Bishops as an interest group in welfare and health care reform.

Figure 1.

The Bishops as an interest group in welfare and health care reform.

- (1)

For welfare reform, the Republicans held all the cards, having just won the majority in Congress as a result of the 1994 “Contract with America” election, and though they didn’t have a Republican President, the Democrat in the White House needed to sign a welfare bill to ensure his reelection bid. Compromises were primarily made within the Republican Party and Democrats were left out of the debate. For health care reform, the Democrats held all the cards, having just won the presidency and majorities in both houses of Congress. As in welfare reform, compromises were made within the party, only this time it was the Democratic Party.

- (2)

For welfare reform, the Bishops were opposed in principle to the bill itself, which ended the entitlement to welfare. Their ultimate goal was to see the bill fail; short of that, they tried to limit what they viewed as its negative impacts. In health care reform, the Bishops agreed wholeheartedly with the general premise of the bill, but they were morally opposed to one provision (expansion of abortion coverage) that led them to oppose the entire bill.

- (3)

In both cases, the bishops ultimately opposed passage, and, in both cases, they lost.

Definitions of winning and losing, however, may be in the eye of the beholder, which is what makes evaluating interest group impact so difficult. While liberal interest groups were cut out of the debate in welfare reform, the bishops were highly involved in health care reform. In addition, although they themselves disagreed with the final abortion compromise, a compromise was indeed made. This compromise made the pro-choice groups unhappy, and may not have been made without the bishops early involvement in the issue. From the bishops perspective as well, registering their moral opposition to abortion was not an inconsequential achievement.

The bishops are like other interest groups, in a variety of ways. They have professional staff members who lobby in Washington, and they can sometimes deploy a bishop to put pressure on a member of Congress from his diocese. They have expertise in the provision of social services such as health care and welfare. The bishops also have a larger “membership” of Catholic parishioners and can use, rather than a “bully pulpit”, the actual pulpits of their parish priests to get their message across, which they did in the case of health care reform. They used both insider and outsider tactics in both health care and welfare reform. The inability to compromise, or to accept compromise is at the root of the bishop’s failures in both issues. According to a famous quote attributed to Otto von Bismarck, “politics is the art of the possible, the attainable—the art of the next best” [

91]. Compromise is necessary to get things done, especially in a society as large and diverse as ours, and in a separated system such as ours. However, compromise is at odds with a worldview predicated on an unchanging code of moral authority. How can you compromise on morality and be true to your faith? The bishops could have claimed victory in health care, because they got what they wanted in general: government provision of health services, and increased insurance coverage for millions of uninsured poor. However, the bishops were unable, unwilling or, in their view, morally constrained from making that compromise on abortion:

Abortion is the taking of innocent life and killing is different from having as much access to health care as we want. In a sense, we all want everyone to be covered—and we’re not compromising on this—but it doesn’t have the same moral immediacy that abortion does.

While other groups can claim to represent the views of their membership, the bishops represent a hierarchical organization. The bishops do not see themselves as representing their flocks, but educating them. They do not, however, have ultimate control of even the most faithful Catholics, as seen by the willingness of the Catholic nuns to break from the bishops and support the compromise on health care. This gave broad political cover to Catholic Democrats who wanted health care reform to succeed, who wanted to be on record as supporting a historic initiative and who wanted to win reelection the following year. Faithful Catholics announced their opposition to abortion, but voted for the bill, putting their own sense of morality (or perhaps political expediency) ahead of the teachings of their bishops.

In terms of the initial hypotheses for welfare, Catholic interest groups were only effective on one issue, and that issue was narrow and incremental (hypothesis 3) and they worked in a coalition with other interest groups (hypothesis 1). The groups did have access to decision-makers (hypothesis 4) and used insider techniques (hypothesis 2). Their access was somewhat limited, and they were not able to translate it into legislative success. Although their best resource may be information in other cases (hypothesis 5), in this instance their expertise was not an asset. In fact, their moral suasion seemed not to come into play. Not only did they not convince Catholics in Congress, Catholic public opinion was no different from the public opinion of others in its agreement with ending welfare. Finally, the Catholic groups were lobbying to maintain the status quo (hypothesis 6), but conversely, they were unsuccessful in doing so. Welfare reform may be the exception that proves the rule. No matter what resources an interest group or coalition of interest groups brings to the table, the process is inherently political. The election year of 1996 opened an unusual window of opportunity, and the Republicans were intent on using it to their best advantage.