Abstract

The public profile of the Roman Catholic bishops of the United States results not simply from their own interventions in political life, but from the broad array of actions and actors within “public Catholicism” broadly conceived. This article assesses the contemporary profile of the American bishops from this broad angle, particularly in light of new dynamics under the papacy of Francis I. It does so by documenting public Catholicism’s presence in ecclesial institutions, other public institutions, and lay-centered social movements (particularly faith-based community organizing) and via a case study of the healthcare reform debate around the State Children’s Health Insurance Program and the Affordable Care Act. Cultural and institutional factors shaping Catholic public presence are analyzed in three dimensions of social life: institutional leadership; authority dynamics within the Church; and the culture of prayer, spirituality, and worship in parishes. Finally, the conclusion discusses the key dynamics likely to shape the future of public Catholicism in America.

1. Introduction

This article analyzes the public profile of Roman Catholic bishops of the United States, with a particular eye toward how that profile is changing under the dynamic conditions created by the governance of Pope Francis. However, the public profile of the American bishops emerges not just from their own public interventions, but much more fundamentally from the broader institutional profile of the Catholic Church in America which they lead. Therefore, before projecting what current dynamics may portend for the future, the article first pays attention to the structural conditions resulting from recent decades of American Catholic public life—both the high-level national picture within church and society, and more diffuse dynamics within broad segments of the Catholic community and American society as a whole. That is, I consider “public Catholicism” broadly conceived as well as the more specific profile of the American bishops.

If considered as a static picture, this analysis would suggest two key insights: first, institutionally public Catholicism has built and maintained an impressive presence at all levels of church and society, which positions it to exert significant influence on American public life, in ways I will argue are entirely appropriate in a democratic public sphere. Second—and in analytic tension with the first insight—specific cultural dynamics within the Church have systematically undermined the wider impact of public Catholicism. However, that static picture obscures more dynamic changes underway: Pope Francis is having his most significant impact on the Catholic social imagination and thus the cultural dynamics within the Church. As a result, public Catholicism may be entering a new moment of potential influence—if the bishops and other sectors of American Catholicism can successfully overcome the cultural dynamics that have thus far undermined their influence. Thus, this article offers a reflective essay on the contemporary conditions and future promise of public Catholicism under the leadership of the current American bishops. I hope to offer insight, if not into the American Catholic future itself, at least into the key dynamics that will give birth to that future.

Anyone hopeful for democracy in the United States—Catholic or otherwise—might well be troubled by the state of American public Catholicism today. Catholicism has certainly not lost its public voice. Catholicism’s historically fruitful dialogue with American culture—carried on in diverse ways by leaders both lay and clerical, from Bishop John Carroll and Orestes Brownson in the 18th and 19th centuries to John Ryan, Dorothy Day, George Higgins, Jack Egan, Thomas Merton, and Cardinal Joseph Bernardin in the 20th century—in some ways continues today [1]. However, amidst the linked sexual abuse and authority scandals in the Church, and acute political polarization in the wider society, leaders in both church and society seem increasingly tone-deaf to the appropriate give-and-take of public dialogue in a democratic society. This chapter argues that, if Francis and the bishops can vigorously re-launch that historic dialogue, the Church’s social teaching and institutional presence hold vast potential to play a leavening role in American public life. Pope Francis appears to desire this kind of re-launch, but with an important new twist analyzed below. I argue that if American Catholic leaders resist such a re-launch, the Church risks sacrificing its historical role as an important public interlocutor in the evolution of American society, in the name of a more sectarian self-understanding that has emerged over the last two decades.

The article first outlines an analytic framework through which to examine the relationship between public Catholicism and American society. Next, I extend José Casanova’s influential analysis of “public religion in the modern world” to document Catholicism’s public presence as carried in three sectors of American life: ecclesial institutions, from the national bishops’ conference and state-level bishops’ conferences, to dioceses/archdioceses, Catholic universities and local parishes and schools; other public institutions, ranging from Congress and the Supreme Court to state and local elected officials and non-governmental institutions; and lay-centered social movements [2]. I portray public Catholicism in action through a brief case study of the Catholic involvement in the 2007–2010 healthcare reform debate that led to the Affordable Care Act, otherwise known as Obamacare. The core of the analysis then considers cultural and institutional factors shaping Catholic public presence in three areas: institutional leadership, authority dynamics within the Church, and the culture of prayer, spirituality, and worship in parishes. Finally, the conclusion discusses the key dynamics likely to shape the future of public Catholicism in America.

2. Thinking about Public Catholicism: An Analytic Framework [3]

Catholics and non-Catholics alike may be tempted to identify “public Catholicism” with the public voice of the bishops in addressing social policy. Certainly the bishops represent the most crucial dimension of the Church’s public witness, but it is a mistake to reduce public Catholicism only to this dimension. It is far better to start with an adequate understanding of the notion of “the public” in order to properly consider what we mean by public Catholicism.

Contemporary democratic theory holds that democracy is not simply the product of elections and representative institutions, but rather is built upon a foundation of societal-wide dialogue through which citizens reflect upon their experience and current situation, and establish priorities and commitments that flow into and shape the political process through those elections and representative institutions [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Since Vatican II, the Catholic Church has largely embraced this understanding of democratic institutions; certainly Pope Francis appears deeply committed to democratic institutions in national decision-making and to a process of political inclusion whereby all sectors of a national population are part of societal dialogue [14,15].1

Democratic deliberation thus occurs at multiple levels: among citizens, between leaders of all kinds of institutions, and among political leaders. All such sites constitute what democratic theorists call the “public sphere”. Although this democratic ideal posits that all members of a society participate in the public arena on equal footing, in reality differing levels of power mean some people shape public dynamics more than others—and some people may be illegitimately excluded due to lack of cultural or economic resources, or due to gender, race, sexual orientation, etc. Egalitarian themes within Catholic social teaching become especially relevant here, due to that tradition’s emphasis on judging societal arrangements partly through the lens of their impact on those who were previously marginal in society [16,17,18].

In this way of understanding the public sphere, “public Catholicism” cannot be narrowed to the role of the Catholic bishops. Doing so would collapse to a few voices what is objectively a far more diverse set of individual voices and institutional channels through which the Catholic tradition shapes American consciousness. Thus, we are dealing with public Catholicism everywhere that the Catholic worldview is brought to bear in deliberations within the public sphere undergirding American democracy. In a sense, then, it is the whole Catholic tradition that sustains a dialogue with American culture, with that dialogue carried on at many levels simultaneously, by theologians and Catholic scholars in their intellectual work; by deacons, religious sisters and brothers, and priests in preaching and teaching; by lay Catholic leaders within secular institutions; by Catholic businessmen and politicians within corporations and government. Ultimately, the Catholic understanding of the authoritative office of the bishops means that they are arbiters of the Catholic tradition’s stance in this societal-wide dialogue; however, as we shall see, without these other voices that dialogue would be much impoverished. The voice of the bishops thus constitutes the central flow among many that make up the overall current of American public Catholicism, with other important channels, cross-currents, and subterranean flows also important to the overall picture. This portrayal emphasizes the actual ways that Catholicism relates to American culture, and is also consistent with democratic political norms, in which social policy is driven by effective argumentation and political discernment, not via a privileged Church voice directly shaping political life.

In utilizing this model of church-society relations within the public sphere, we must remember that there are two different modes of authority at work in the two settings. Within the Church, authority is ultimately hierarchical in structure. It is “top-down”, although not absolutist in that when internal church dynamics are healthy, multiple currents of Catholic teaching are in play within that hierarchically structured authority; however, it is inherently hierarchical, with the bishops holding an authoritative voice that Catholics are expected to take seriously as they make decisions on public matters. In contrast, within the wider society authority is democratically structured through participative and representative institutions, often colloquially described as “from the bottom up.” In fact democratic authority is a good deal more complex than that phrase implies, with multiple hierarchical authority structures in play, including scientific authority, authority rooted in corporate and (to a much lesser extent) labor union hierarchies, and the authority attached to icons of popular culture and religious belief. However, the top-down versus bottom-up imagery captures a key distinction between authority within Catholicism, structured by complex authoritative hierarchy, and authority within the democratic public sphere, structured by democratic relations.

Used poorly, such a broad understanding of the public sphere might risk becoming analytically useless by requiring us to pay attention to everything at once. However, here we can avoid this risk: as a relatively coherent spiritual and intellectual tradition that revolves around specific institutional nodes, Catholicism lends itself to a focused analysis limited to a relative handful of such institutions.

Institutions of Public Life: Ecclesial and Secular

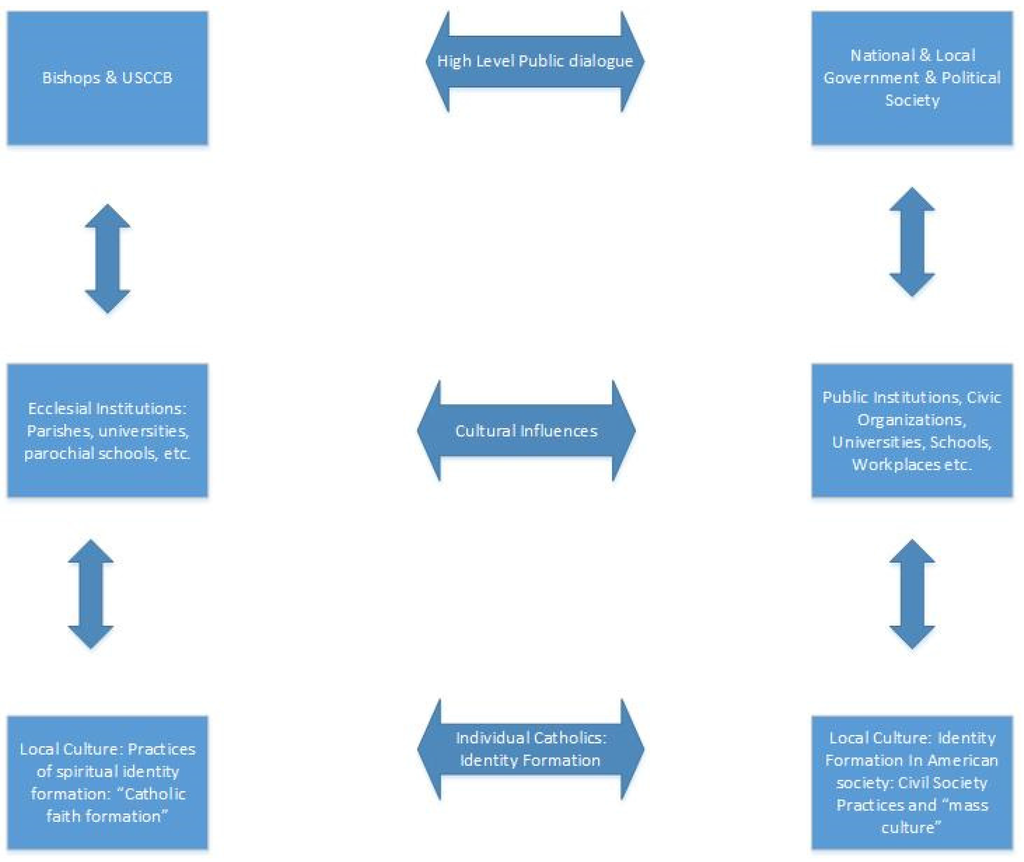

We can think of Catholic public influence being exerted through two broad channels. On one hand, Catholic teaching flows down and out to the wider society, originating in papal and episcopal teaching authority and flowing through ecclesial institutions explicitly committed to Catholic worldview and practice. On the other hand, Catholic worldview and social commitments might flow upward through the institutions of society, as a result of the cultural influence of individual Catholics in civil institutions and electoral politics. Figure 1 sketches these complementary potential channels of Catholic influence, as well as an important “middle” route of influence.

Figure 1.

Public Catholicism—channels of influence between church and society.

As depicted in Figure 1, analyzing public Catholicism requires paying attention to a diverse array of institutional settings, from parishes and diocesan organizations to national-level episcopal structures, and from local civil society to the Supreme Court. Neither those analyzing the public role of Catholicism nor the bishops themselves do well to reduce the influence of Catholicism on the voice of the bishops; rather, the Catholic tradition shapes American public life through the variety of channels shown here. Figure 1 assumes a relatively free flow of culture between the ecclesial sector and the wider social world. This is in keeping with the contemporary reality that American Catholics no longer exist in a separate, sectarian subculture within American society, as arguably was the case up through the 1950s. Rather, Catholics have fully joined the broad American cultural and social milieu, with most individual Catholics operating competently within both Catholic settings and the wider culture [19,20,21].

Although public Catholicism exerts social influence through both elite dialogue and more dispersed cultural flows above the level of the individual, in the long term it will only have significant influence to the extent that the complex and cross-cutting identity-forming pressures produce individuals with discernibly “Catholic” identities. For if there is no distinction between being Catholic and being American, then American Catholicism simply dissolves into the wider mainstream culture. This makes understanding what Catholics call “faith formation” crucial to assessing public Catholicism. This is the “identity formation” level shown in Figure 1, and includes the practices of spirituality and worship centered in parishes, as well as the intellectual commitments shaped by theologians and disseminated through Catholic teaching and preaching.

Though some regret the fact that lay Catholics now live fully within both church and society, lamenting it as the death of a distinctively traditional Catholicism, sociologically it reflects American Catholics’ successful upward mobility over several generations, and American society’s successful dismantling of anti-Catholic nativism. It also represents the opportunity for American Catholicism to effectively shape the wider society: as long as Catholics resided in a subculture of their own, their ability to reshape the wider culture was quite limited. By bridging between broad American cultural patterns and the Catholic worldview carried within parish life, contemporary American Catholics bring Catholicism to bear within the ongoing evolution of American culture, both at the grassroots and at higher institutional levels.

This brings us to the “cultural influence” level shown in Figure 1. Beyond individual identity formation, equally or more important is the way that public Catholicism shapes and is shaped by broader American culture. To think about this, it is helpful to imagine American society not only as a collection of individual Americans, but also as the product of interweaving cultural strands that shape American life [22]. That is, American life is a stream made up of a variety of cultural currents, intermingling in complex ways yet preserving themselves as evolving cultural traditions (including traditions based upon democratic commitments, religion, ethnic and racial identities, mass consumerism, “new age” and artistic humanism, utilitarianism, nationalism, etc.). In this metaphor, public Catholicism is one such cultural current, shaping and being shaped by American culture in ways not reducible to individual identity formation. Rather, public Cholicism also bridges between authoritative teaching internal to the Church and the flow of democratic authority in American society.

From the standpoint of advocates of public Catholicism, this bridging represents an advance, rather than a retreat, if and only if Catholic culture preserves sufficient coherence to play that role. Theologically, such an understanding harmonizes well with Gerhard Lohfink’s analysis of the early church as a “contrast society” to the wider culture [23]. Two points are crucial here, which can be best appreciated by extending the “bridging” metaphor: a bridge must be securely anchored at both ends, or it cannot function as a bridge. Thus, at one end, the Church as a contrast to society must coherently articulate and clearly live out its own identity and self-understanding. At the other end, the Church must not only in principle affirm democratic life and freedom of conscience, but also in practice accept the dynamics of democratic authority in political decision-making. That is, from the standpoint of Catholics, “bridging” must be faithful to the Church’s self-understanding; simultaneously, from the standpoint of the non-Catholic public, this bridging represents a legitimate voice for public Catholicism if and only if the key actors in public Catholicism accept the rules of the democratic public sphere: viz., that religious leaders (1) enter the public arena to try to convince others that their views will best serve the common good; (2) recognize that pursuit of the common good is a complex political art and a skilled craft, in which specialists (called politicians) pursue partial victories that pave the way for deeper future victories; and (3) enter the public arena open to the possibility of others providing convincing counter-arguments, i.e., that they might revise their views.

Refusal to accept these terms of democratic life, in the name of a purer absolute good, potentially leads to the situation of the Catholic Church behaving as a sect—an oxymoron in traditional Catholic self-understanding, but nevertheless a contemporary alternative, as we shall see.

The notion of the Church as a contrast society is thus different from the notion of a Catholic subculture. In the former, the Catholic community exists in relationship to but some tension with the wider society, and accepts the terms of the “bridging” metaphor discussed here. In the latter, the Catholic community understands itself, and to some degree actually exists, in isolation from the wider society—and often as simply resistant to it. Accepting the democratic norms of contemporary public life has been historically difficult for the Catholic tradition to embrace, coming only via the Second Vatican Council and subsequent papal statements – both influenced by the American Catholic experience via the theologian John Courtney Murray [24,25].

Catholics (whether conservative or progressive) who prefer a more prophetic/critical stance towards American culture will surely respond that no prophetic social role is possible if American Catholicism simply embraces the wider culture. I do not argue for a blind embrace of the wider culture. If the Church understands itself as “leaven” for the “dough” of the wider society, it must to a significant degree serve as a contrast to that society—“leavening” presumes a distinction between the leaven and the dough. Thus, the notion of the Church as a contrast society returns us to the theme of identity formation: if church institutions can effectively shape an American Catholic identity that holds its own amidst the pressures of popular culture, then American Catholics are, as demonstrated below, impressively positioned to shape the wider culture in ways not previously possible. However, the point here is that prophetic Catholicism cannot reject all normal political compromise if it wants to play this leavening role.

Thus, the American bishops—and public Catholicism more generally—stand institutionally and culturally on complex terrain. The next two sections begin a concrete analysis of that terrain, by considering the profile of a broad set of church-related institutions and their role in one of the most important recent debates in U.S. politics.

3. Catholicism’s Institutional Presence in American Life

Catholicism is brought to bear in public life through church-sponsored institutions headed by the bishops, through church-related institutions that the bishops influence less directly, and through the presence of Catholic individuals in autonomous social movements.

In briefly outlining Catholicism’s presence in American life, I pay attention both to the raw numerical weight of Catholic institutional and individual presence in these settings, and to the subtler dynamics of Catholic influence within these institutions. I divide the discussion into ecclesial institutions, other public institutions, and lay-centered social movements—recognizing that the level of institutional control by Catholic bishops varies substantially across these levels. Such episcopal control is strongest in official ecclesial institutions directly affiliated with dioceses, weaker in those affiliated with religious orders, and weaker still vis-à-vis public institutions and lay-centered social movements (although episcopal influence in the latter varies greatly). This creates a significant pluralism of Catholic perspectives and directions of influence, despite outside perceptions of a monolithic Catholic voice.

3.1. Ecclesial Institutions

In terms of sheer institutional presence, Catholicism maintains an impressive and growing weight in American society. In 2007, there were 19,044 parishes in the United States, spread broadly across the geographic regions, social settings, and—importantly—the districts that elect presidents, congressional representatives, state officials, city council members, and school boards [26]. This represents an increase of 1102 parishes since 1967 (6% increase), though there has been a decrease of 583 parishes since 2000 (3% decline), as dioceses strapped for financial resources and ordained clergy have closed some churches.

Far outpacing this slow, four-decade rise in the number of American parishes, the number of Catholics per parish has increased significantly, from 2614 to 3544 members in the average parish (36% increase). This has been driven by a dramatic increase in the total Catholic population, from 46.9 million to 67.5 million (44% increase since 1967), primarily due to immigration. Simultaneously, the number of ordained men who lead most of these parishes has declined 40%, and the number of religious sisters and brothers who once provided crucial additional staffing in parishes, schools and other settings has fallen most precipitously of all (63%). As a result, the number of Catholics per priest or religious brother/sister has risen by 220% during this four-decade period [27].

From the point of view of cultural sociology, we can assume that where institutional Catholic influence wanes (as reflected roughly by declining numbers of priests and religious sisters/brothers, or thinner institutional life generally), the identify-formation dynamics among lay Catholics will be increasingly influenced by mass American culture. That is, individual identity formation is shaped by both internal Catholic and wider cultural dynamics; where the former is weaker, the latter may hold greater sway.

However, a wide Catholic institutional presence remains within American culture. Beyond parishes, the church’s presence includes 557 hospitals assisting some 83 million patients per year, often at times of personal crisis, and often with explicitly Catholic pastoral care offered alongside medical expertise. Their influence is difficult to assess in any rigorous way, but they provide medical attention explicitly rooted in Catholic values and pioneered such innovations as clinical pastoral care that combine medical and spiritual solace. In addition, approximately 1004 day care centers and 2856 specialized social service centers serve a broad constituency of low- and middle-income non-Catholic and Catholic clients. Some 769 parish-affiliated high schools and 583 other Catholic high schools serve approximately 608,000 students (nearly a fifth of who are non-Catholic) during the key identity-shaping teen years; and more than 6500 Catholic schools serve more than 1.6 million elementary school students. Finally, more than 3.8 million elementary and high school aged children are reported to partake in religious education through parishes nationwide. All this adds up to an impressive Catholic institutional presence in American life, albeit one whose cultural influence is difficult to verify and in any event has likely waned significantly in the face of societal changes of recent decades [28].

Meanwhile, the state of American ecclesial finances has deteriorated markedly. As Francis Butler noted in 2006, U.S. dioceses “face an era of rising costs, diminishing reserves and insufficient income...Dioceses appear to be running through their reserves at an alarming rate...The reason for this is simple: it’s due to the outflow of grants to sustain parishes operating at a loss” [29,30]. Butler went on to note these deficits are primarily associated with parishes housing parochial schools.

Since that time, these structural deficit problems have been exacerbated by the costs of settlements with victims of clergy sexual abuse: from 2004 to 2008, American dioceses and their equivalents faced costs related to sexual misconduct allegations that varied between $139 million and $498 million annually. With a total of almost $1.7 billion paid out over that period and approximately 60% paid directly by dioceses (40% paid by insurance), this has been an enormous drain on church finances. In addition, the finances of men’s religious communities deteriorated dramatically: $281 million was paid out to settle sexual abuse cases from 2004 to 2008. These financial liabilities accumulate further since 2008; whether they have now peaked remains unclear, as the financial sums and the numbers of new allegations show no consistent pattern. Incalculable but serious damage to the church’s public credibility has also been done by the supervisory malfeasance of some bishops, which exacerbated the sexual abuse scandal. That this negligence partly reflected prevailing practices in the wider culture has not lessened its impact. The resulting authority scandal is beyond my purposes here, but has surely undermined the credibility and legitimacy of the bishops’ authoritative voice [31].

More complex has been the financial situation of women’s religious communities. Some have prospered financially by selling off medical and other institutions to endow their communities or to promote social justice and charitable endeavors; many others confront profound financial crises as members aged and faced high medical costs and low recruitment of new members.

The resulting ecclesial financial difficulties, combined with the rising influence of some bishops resistant to national episcopal influence in their dioceses, led to an important downsizing of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) during 2005–2006. The retrenchment instituted a leaner organizational structure and sharp reductions in staffing. While some of this reorganization may have been overdue, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that it also represented a significant scaling back of organizational aspiration and capacity, and a lower priority to some areas of historic episcopal priority: whereas the bishops’ most prominent interventions in public discourse in the 1980s involved criticism of nuclear weapons policy, economic inequality, and American intervention in Central America, in recent years they have involved criticism of abortion rights, embryonic stem cell research, gay marriage and other forms of domestic partnership legislation. This represents an important shift of public profile, albeit one that should not be exaggerated—after all, throughout these decades the bishops have also continued to speak out on a wide spectrum of social issues, including opposition to the death penalty, concern about poverty in America, and support of immigrants’ rights. Nonetheless, a greater emphasis on ‘conservative’ issues and a more partisan tenor of political messages has been widely perceived, along with a de-emphasis on the integrated “seamless garment” approach advocated by the late Cardinal Joseph Bernardin.

Throughout these shifts, the USCCB has remained the Catholic bishops’ primary voice in national public affairs, through such activities as educating and lobbying congressional representatives regarding the bishops’ issue priorities; the periodic promulgation of statements such as Faithful Citizenship, intended to inform Catholic political choices during the 2008 elections and since; and the anti-poverty program Catholic Campaign for Human Development, which each year distributes some $10 million in funding to empower poor communities.

Other ecclesial institutions have fared far better in recent years. A less-known story involves the continuing work and influence of Catholic lobbying efforts through the “Catholic conferences” sponsored by groups of bishops in some 32 states. David Yamane [32] discusses the influence of these bodies on public policy at the state level, on issues ranging from capital punishment to abortion to anti-poverty policy to education funding; he argues that the bishops’ lobbying efforts at this level have been largely unaffected by the recent sex and authority scandals, and remain quite strong (at least as of 2004). Much less certain is the effect of the recent church financial implosion and the broader economic downturn, and whether the state conferences have been able to sustain their funding and activity.

Catholic universities and colleges represent another key facet of the public profile of American Catholicism. While their relative independence has been objectionable to some bishops, that independence also helps sustain the broad historic voice of Catholicism in public affairs. It is a diverse profile, from small colleges that are quite insular, to large liberal arts colleges and research universities that are very much engaged with the wider culture. Furthermore, their political and theological profiles vary enormously: some have embraced traditionalist efforts to reinstate a tightly defined Catholic orthodoxy while others have fused rather acritically with the mainstream culture of American higher education, and still others have embraced Catholic teaching on social justice as defining their central mission.

These complex internal dynamics too often obscure what is in any case an impressive profile in higher education: 236 Catholic colleges and universities, spread out across all 50 states, enroll more than 900,000 students and represent a rich pluralism of emphases and identities within an at least potentially unifying Catholic vision of contemporary life [26]. Enrollment grew by almost 61% between 1980 and 2005. This strong institutional presence does not necessarily translate into effective identity-formation processes. We simply do not know a great deal about whether these colleges and universities are effectively passing on a Catholic ethos, spirituality, vision, and social commitment (in whatever terms a given observer defines those things) or simply reproducing the values of the wider society. However, they have certainly shaped generations of American leaders in church, society, business, politics, and the legal system. The best data come from [33,34] and raise important doubts about the efficacy of current church practice in this regard.

Finally, church-sponsored communications media remain an important aspect of the Catholic public profile. The focus and technological basis of the media used continue to shift: a Catholic media profile that once emphasized magazines, newspapers, and radio, today increasingly emphasizes different media [35,36]. Catholic television stations and websites now abound, and the Vatican now projects a sophisticated Internet presence. Thus, though such publications as America, First Things, the National Catholic Reporter, the National Catholic Review, and The Wanderer continue to be read and to exercise significant influence in their particular markets, the broader Catholic market appears increasingly to belong to television and the Internet.

Good studies of this shifting religious media terrain are rare, but a few generalizations seem warranted. First, and perhaps most importantly, all these media outlets combined appear to have lost market share to the dynamic growth of two other sectors of religious media; Evangelical media and magazines reach out to a broad mass market across nearly all regions and social sectors. Additionally, a smaller set of media outlets promote “contemporary spirituality” of Buddhist, Hindu, Sufi, Sikh, “new age”, and other varieties, especially among the future societal leaders being educated in elite universities and socialized in urban centers. Second, Catholic television appears to be dominated by traditionalist Catholicism, with programming devoted to some of the least intellectually reflective pietistic practices of contemporary Catholicism and to the most sectarian Catholic intellectuals. This programming both reflects and promotes an authentic part of the current spectrum of Catholic practice; its dominance nonetheless reflects a dearth of much televised presence of other points on that spectrum. Third, the Catholic Internet presence is far more diversified, better reflecting the broad “catholic” spectrum of views and emphases; here, conservative and liberal positions, official and alternative Catholic voices, and clergy and lay perspectives all find a voice.

Two final notes regarding ecclesial institutions. First, under John Paul II the Vatican built a multilingual online presence via an official website, which has since been extended to a YouTube channel, and sophisticated social media capacity—a capacity that Pope Francis has used to strong effect. The USCCB has done likewise in English and Spanish. Both have made official teachings more directly available in forms accessible to lay Catholics. However, this will only serve to advance ecclesial insight and influence if it is accompanied by a parallel effort to foster dialogue within the Church and critical engagement across perspectives and cultures, in ways capable of shaping democratic dynamics in the public arena [37]. Second, political historians have shown that the most influential civil associations in American history have been built on “federated” organizational forms combining intensive local participation with state- and national-level structures [37]. The Catholic structure of parishes, (arch)dioceses, state conferences, and the national bishops conference creates precisely such a federated structure, suggesting that the Catholic tradition might still be capable of articulating a strong external voice vis-à-vis American public life. Again, for such a voice to be effective, legitimate, and authentically Catholic, it must emerge from long-term symbiosis between authoritative central teaching and decentralized lay initiative, both appropriately affirming the pluralistic principles of a democratic public arena. Pope Francis and in particular his Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace appear to be committed to fostering such symbiosis, as evidenced by their strong central interventions in debates on climate change and economic inequality combined with their repeated calls for grassroots action on a global level and the convening of a series of “World Meetings of Popular Movements” [15].

3.2. Other Public Institutions

Beyond the official and semi-official ecclesial institutions discussed above, individual Catholic leaders in prominent positions in other public institutions also project public Catholicism into the wider society. These include a wide variety of Catholic intellectuals teaching and writing from within high-profile universities, a small portion of them holding endowed chairs of Catholic Studies and many more embedded in traditional professorial roles, as well as intellectual Catholic journalists such as E. J. Dionne and Ross Douthat [38,39]. Second, Catholics have come to play a remarkably prominent position in the court system of the United States, particularly at the level of the U.S. Supreme Court, where two-thirds of the justices are Catholic [40]. Third, Catholic elected officials continue to exert influence at all levels of American government, from schools boards, city councils, and mayors’ offices to the halls of Congress; we know little about the preponderant direction of this influence, given the diversity of political views of Catholic politicians.

What all this will add up to in terms of future electoral influence is difficult to predict: the Catholic vote swung toward Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012, despite assertive episcopal intervention against him due to his stance on abortion, gay marriage, and later “religious freedom”. Only future elections will show us whether this simply reflected widespread disenchantment with the Republican Party following the Iraq disaster, the bungling of Hurricane Katrina relief, and the “Great Recession,” or began a long-term shift back to voting for Democratic candidates. If the latter is the long-term pattern, research will be needed to assess whether it results from a widespread turning away from episcopal authority, or from heightened lay political discernment exercised autonomously but in dialogue with episcopal authority. That outcome likely depends partly on how the bishops choose to lead in the years ahead—and on the work of grassroots Catholics in social movements to mobilize church teachings on a variety of terrains.

3.3. Lay-Centered Movements

At the grassroots level, a wide variety of lay-centered movements are shaping the cultural terrain of American Catholicism. Some of these are familiar, such as the pro-life/anti-abortion movement, which is partly episcopally funded and draws on Catholic parish life in significant ways. A variety of Catholic social justice movements such as Pax Cristi and movements for solidarity with human rights activists in other societies, although only weakly present in most parishes, engage students at public and Catholic universities via campus ministry efforts, worship at “Newman Centers”, and issue-specific outreach efforts. The Catholic charismatic movement and other apostolic movements continue to exert an important influence, both through local parishes and in less institutionally organized venues [41]. Meanwhile Opus Dei, Catholics United for the Faith, and other conservative movements seek to bolster more traditionalist interpretations of Catholicism, lobby for “restorationist” interpretations of Vatican II, and pressure bishops and priests to clamp down on liberal trends within American Catholicism. On the more liberal side, movements such as Call to Action, Catholics United, and Catholic Alliance for the Common Good seek to heighten the profile of Catholic social teaching on a variety of issues, and to press for changes in Catholic teaching and authority structures. All these are important and understudied facets of public Catholicism.

A less well-known—but perhaps more important due to its role in public Catholicism—lay-centered movement also plays a significant role in American Catholic life. Many Catholic parishes in low-income urban areas, and some suburban and rural parishes, participate actively in “faith-based community organizing” efforts (FBCO, also known as broad-based or congregation-based community organizing). Community organizing has received recent attention due to Barack Obama’s early experience in Chicago, but such efforts have for more than six decades involved Roman Catholic, historic black Protestant, liberal and moderate Protestant, Jewish, Unitarian, and (more recently) Pentecostal congregations in work to influence local and state-level public policy. They have built a track record of influencing public policy to benefit low- and middle-income communities on such issues as public education, economic development, housing, healthcare, and policing. Sponsoring most of this work are several national FBCO networks, including the PICO National Network; the Industrial Areas Foundation; the Gamaliel Foundation; Direct Action, Research, and Training; and the regional Inter-Valley Project and Ohio Organizing Collaborative; plus a few independent efforts. These networks link more than 190 local coalitions present in 40 states, essentially all major metropolitan areas, and many other primary cities of the country. In the past decade, the FBCO field has been analyzed insightfully by both scholars [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] and practitioners [54,55,56,57]. The field had grown dramatically over the prior decade, with 42% more coalitions in 2011 than in 1999. The typical FBCO coalition brings together roughly two dozen organizational members (mostly religious congregations, but also labor unions, immigrant organizations, neighborhood associations, and others); it then trains leaders from within those organizations to identify and advocate for policies that better serve poor, working-class, and middle-income communities [42].

As of 2011, for which systematic national data exist, those organizations incorporated 4150 member institutions (about 80% of which are religious congregations, the rest mostly unions, public schools, and neighborhood associations). More than a quarter of the sponsoring congregations are Catholic parishes. A third of governing board members and paid organizers are Catholic, as are 42% of coalition directors/lead organizers. When well implemented, this organizing model empowers lay leadership reflective of Vatican II’s emphasis on the laity’s mission “in the world.”

FBCO work on issues has often reflected the public policy priorities embodied in Catholic social teaching as articulated in papal and American episcopal statements. That is no coincidence: for 35 years, the bishops’ Catholic Campaign for Human Development has been the most consistent source of funding for faith-based community organizing efforts throughout the country; many religious orders also fund this work. While CCHD funding now only represents about 15% of funding for local FBCO coalitions (down from 19% in 1999), that support has been crucial to strengthening the field’s organizational infrastructure. Almost two-thirds of coalitions receive CCHD funding in a given year, and CCHD often provides the start-up funding that has helped the field grow from a scattering of struggling organizations in the early 1980s to its current wide geographic profile. This Catholic involvement has shaped the ethos of the field in significant ways. For example, whereas the governing boards of most civil society organizations heavily over-represent well-off constituencies, 22% of FBCO governing board members have household incomes under $25,000/year and fully half have household incomes under $50,000/year—the latter almost exactly representative of U.S. households. This strong representation of low-income leadership almost certainly results from CCHD sponsorship: the organization insists that funded organizations include substantial leadership by low-income people themselves. Likewise, over half of board members are non-white.

Two other important lay movements are also not widely recognized: the many small “faith sharing” groups functioning within or alongside Catholic parishes, and the grassroots movement Voice of the Faithful. The faith-sharing groups are decentralized and reflect many different strands of Catholicism, typically meeting weekly or monthly to read scripture, reflect on their faith lives, pray together, and (more rarely) engage in service or advocacy work together [58]. Voice of the Faithful argues for increased accountability of episcopal structures and a greater lay share in church leadership, partly in response to the sexual abuse crisis. Though sometimes perceived as hostile to church leaders, the organization appears to combine strong Catholic religious identity, a desire for a thriving institutional profile for public Catholicism, and insistence on greater transparency and accountability.

As carried in ecclesially-linked institutions, other public institutions, and lay movements, public Catholicism thus enjoys an impressive profile in American public life. Whether through their direct governance or through inspiration and teaching, the bishops shape all these dimensions of Catholic public presence. However, whether it all adds up to significant Catholic influence on American society today is less clear. Indeed, in its direct impact, public Catholicism often seems to add up to less than the sum of its parts. In order to understand the complex place of the Catholic tradition within the American democratic arena, the next section analyzes the role of public Catholicism in one crucial national debate of recent years.

4. Case Study of Public Catholicism: The Healthcare Reform Debate

The 2009–2010 national healthcare debate, along with the health reform efforts preceding it, offers a glimpse into public Catholicism in action. As has been widely noted, the recent debate follows decades of efforts to broaden healthcare coverage in American society. The U.S. bishops had long supported egalitarian access to healthcare, and already in 1981 had issued a major pastoral letter strongly endorsing some form of universal coverage, giving as the first principle to guide national health policy that “every person has a basic right to adequate healthcare” [59]. Despite that advocacy, the desire (of the bishops and others) for broad health reform had remained largely frustrated by the difficulties inherent to reshaping a sector that, by the end of the century, made up nearly a sixth of the national economy. The bishops weighed into the national debate again with a major public resolution in 1993, and with official press releases and voter education efforts in 2002, 2004, and 2006 [60,61]. Over the years, other Catholic public actors also weighed in on the issue, including the Catholic Health Association, various Catholic politicians and intellectuals, and a variety of religious orders.

However, all this had gained little traction. That began to change as the nation’s health crisis worsened, as children’s health became a wedge issue for broader calls for health reform, and when one of the faith-based community organizing networks described above set expansion of healthcare access as one of its primary goals. I focus attention here on the third factor, due to its links to public Catholicism and because the first two factors have been widely reported.

As it first sought to influence national policy, the PICO National Network could draw on the experience of its sophisticated statewide effort in California. PICO California had been active in organizing for broad healthcare access for several years, and its affiliate in San Jose had been central in winning passage of the nation’s first legislation to cover all children in a county (the Santa Clara County Health Initiative). Out of these initiatives, in May 2005 some 315 PICO leaders met in Washington, DC, to begin building PICO’s national strategic capacity. After meeting with about one hundred Congressional representatives, staffers, and DC-based policy think-tanks, they recommended to local affiliates that healthcare become the initial focus of national organizing [62].

Eventually, PICO became a key part of an alliance of groups working for major national expansion of coverage for uninsured children and their parents, focused on the re-authorization of the State Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) scheduled for 2007. In alliance with other organizations, PICO mobilized the primary religious voices that brought faith-based moral framing into the congressional debate [57,63].

In retrospect, this framing of the policy debate within faith-based language appears to have been important, but in one sense secondary: the Catholic bishops and other religious voices had, after all, been providing such moral framing for years. The PICO National Network’s distinctive role emerged as it amplified, diversified, and gave urgency to that faith-based moral framing, but also gave “political legs” to it: through its ability to organize people to articulate the case for children’s healthcare coverage in the nation’s capital and, crucially, in congressional home districts, PICO’s organizing federations in 15 states and some 100 congressional districts (roughly split 55% Democratic and 45% Republican) made the case for bipartisan support for SCHIP expansion. Several times in 2005–2007, PICO brought two to five hundred leaders from low- and moderate-income communities to Washington, DC. In March 2007 alone, these constituents reportedly held 68 meetings with their U.S. Senators and Representatives and another 85 meetings with congressional staff. PICO also worked to move the policy conversation out of the Beltway: local affiliates held 47 town hall meetings and press conferences in congressional representatives’ home districts, and claim to have generated more than 10,000 phone calls and 6700 emails to those representatives regarding SCHIP. Public letters arguing for healthcare coverage for children were delivered to Congress and the White House in December 2006 (with 200 clergy signees) and September 2007 (with 1900 clergy signees). The media provided public exposure to wider audiences, both locally and nationally, via 112 separate stories in local, regional, and national newspapers, plus in-depth stories featuring PICO leaders on National Public Radio and the PBS News Hour [64,65,66,67].

Ultimately, the SCHIP debate was advanced by the combination of: (1) authoritative religious framing of the healthcare issue in moral terms provided by the Catholic bishops and other national leaders of faith communities; (2) the PICO National Network’s ability to provide convincing political “legs” and a prophetic edge to that moral voice; (3) the wider alliance of secular and faith-based policy think-tanks, advocacy groups, and organizing projects that spearheaded the drive to shift the debate from simple re-authorization of the program to significant expansion of children’s health coverage; and (4) the Congressional leadership’s decision to make SCHIP re-authorization a legislative priority. The efficacy of this alliance is signaled most clearly by hard dollars: in 2006 the discussion revolved around whether $12 billion could be provided for reauthorization and by early 2007 the debate had shifted to bipartisan congressional support for $35 billion to underwrite SCHIP expansion. Twice (October 2007 and March 2008) the alliance worked with SCHIP champions in Congress to pass major SCHIP expansions with bipartisan support, but twice the law was vetoed: neither PICO nor the wider alliance could overcome opposition to expanding government’s role in healthcare.

The inability to overcome these presidential vetoes was a significant setback that could have demobilized the effort, but in retrospect it is clear that it laid the moral and political groundwork for a significant victory: in early 2009, having made comprehensive healthcare reform a centerpiece of the presidential campaign, the new Obama administration made SCHIP expansion one of its first legislative priorities, and legislation was passed by Congress almost immediately and signed into law on 4 February 2009. At the signing ceremony in the White House, PICO leaders sat in the front row, flanking both sides of Michelle Obama, as President Obama signed the legislation. PICO’s announcement of the signing thanked its “key child health allies who helped make this victory happen,” and listed the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops among those allies [68].

The passage of SCHIP represented partial implementation of the moral vision of healthcare carried in Catholic social teaching and for which the American bishops had argued for decades. However, despite the difficulty of this struggle, children’s healthcare would turn out to have been the easy issue. The bigger issue of comprehensive reform remained on the horizon, but had become imaginable with the change of presidential administrations: the Obama administration followed up the SCHIP signing with an effort to move legislation forward that would fundamentally reshape healthcare delivery and provide near-universal coverage.

As Congress struggled through much of 2009 to forge some kind of bipartisan healthcare agreement, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops once again weighed in on the public debate, in favor of reform but insisting that it be guided by specific principles. In place of the broad overarching principles of some of the earlier documents (solidarity, subsidiarity, etc.), the bishops specified three principles that they wanted to shape healthcare reform [69]. First, they noted that “reform should make quality healthcare affordable and accessible to everyone,” i.e., that it include effective coverage for the poor and working class. The bishops’ position on affordability was developed in close consultation with PICO, and closely reflected that network’s policy language. Second, the bishops noted it was “essential” that healthcare reform “clearly include longstanding and widely supported restrictions on federal funding of abortion and protections for rights of conscience.” Third, the bishops strongly urged that immigrants receive access to adequate healthcare regardless of their immigration status. The bishops’ position—strong support for deep reform of healthcare, but with affordability, immigrant access, and protection of the legal status quo on abortion as guiding principles—would be reiterated repeatedly throughout the healthcare debate.

As debate raged in mid-2009, fueled by the early “tea party” protests, policy stagnation seemed to set in: the entire reform effort was stuck between liberal insistence on a full “public option” and libertarian protests that had effectively killed the public option. Meanwhile, the PICO National Network and its affiliates were already engaged in extensive educational efforts, and PICO had launched a website devoted to its healthcare work, providing comprehensive information regarding various denominations’ stances in support of reform and resources for congregational study groups and religious leaders’ sermons related to the topic. PICO, and its allied organizations Faith in Public Life (interfaith), Sojourners (evangelical Christian), and Catholics in Alliance for the Common Good (Roman Catholic), had already become the primary religious voices in a broad health reform coalition [68]. To break the policy impasse, in August 2009 PICO held a “National Faith-Based Day of Action” involving 50 prayer vigils and reform rallies in 18 states, specifically intended to counter what organizers viewed as the uncivil and anti-reform character of public debate [70]. PICO and the three organizations listed above also launched a high-profile organizing campaign and an advertisement on religious television. In the “40 Days for Health Reform” campaign, PICO mediated into the national public arena the human stories of doing without healthcare, told in local leaders’ own voices through testimony before Congress and in national press conferences.

These efforts helped counter the policy stagnation and put health legislation back on track, but Congressional support for healthcare reform remained razor thin. In two cliffhanger votes, the fate of healthcare legislation ultimately hung on the votes of a handful of pro-life congressional members of the House of Representatives—many of whom were Catholic. This group of about a dozen lawmakers was led by Representative Bart Stupak, a Catholic who explicitly tied the group’s votes on health legislation to their opposition to federal funding of abortion services. Another central player in the debate was the Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi, also Roman Catholic but strongly favoring women’s access to abortion services. The first vote (7 November 2009) led to the extraordinary situation described by the New York Times as follows:

On Friday (November 6), Ms. Pelosi met twice with Democratic lawmakers from the Pro-Choice Caucus. In between, she huddled with staff members from the bishops conference (USCCB), Mr. Stupak and two other leading Roman Catholic lawmakers, Representative Mike Doyle, Democrat of Pennsylvania, and Representative Brad Ellsworth, Democrat of Indiana. The representatives of the nation’s bishops made clear they would fight the bill if there were no restrictions on abortion. In an extraordinary effort over the last 10 days, the bishops conference told priests across the country to talk about the legislation in church, mobilizing parishioners to contact Congress and to pray for the success of anti-abortion amendments. The bishops sent out information to be “announced at all Masses” and included in parish bulletins, and urged priests and parishioners to tell House members: “Please support the Stupak Amendment that addresses essential pro-life concerns.” They added: “If these serious concerns are not addressed, the final bill should be opposed.” In the end the abortion opponents had the votes, and Ms. Pelosi yielded, allowing Mr. Stupak to offer his amendment.

The Stupak amendment passed relatively comfortably (240–194), with support from pro-life Democrats and most Republicans, despite some consideration among Republicans of voting against the amendment as a way to defeat the overall health legislation [71]. With this settled, the overall healthcare reform legislation passed 220–215.

As the legislation moved to the Senate, the potential impact of the Stupak amendment was a matter of sharp debate: supporters argued that it preserved the longstanding status quo represented by the “Hyde Amendment” of 1974, whereby no federal funds appropriated through Health and Human Services can be used to pay for abortion services. They also argued that this coincided with the policy preferences of most Americans, who continue to oppose governmental funding of abortion even as they support women’s access to it under some circumstances. Opponents argued that, by prohibiting abortion services being provided via any insurance that is paid or subsidized by federal funds, and given the broad impact of the healthcare reform bill on existing health insurance programs, the Stupak amendment would take away abortion coverage already in effect, and thus change the status quo. The complex nuances of the amendment’s impact allowed both sets of advocates to frame the issue as a mortal threat to their supporters. Abortion thus re-emerged as the potential third rail of health reform, lethal no matter how it was handled.

In December 2009, the Senate passed the overall healthcare reform bill, but without the Stupak language. In its place, the Senate version of the bill included language for which Senator Ben Nelson—a Methodist and long-time pro-life ally of the Catholic bishops—negotiated, neither requiring nor prohibiting funding for abortion services, but: (1) requiring insurance companies to segregate premium monies that would cover such services, thus keeping federal money separate and (in some sense) not “paying for” abortion; and (2) allowing individual states to exclude abortion coverage in the state-based insurance “exchanges” created in the health reform legislation. Thus, as of the start of 2010, two versions of health reform were on the table; that both included language restricting federal funding for abortion provides evidence of the significant weight of public Catholicism in political deliberation. However, which would prevail?

The contrasting House and Senate versions—and particularly their divergent language on abortion coverage—led directly to the second cliffhanger vote. By early 2010, larger political dynamics dictated that health reform would only move forward by a two-step process: the House would approve the Senate bill without changes, then immediately pass further legislation “fixing” specific problems (including one central to the Catholic bishops’ position—providing funding to make health insurance more affordable to low-income Americans). In this situation, the precise Stupak language was dead and Republican opposition to the healthcare reform package was unanimous, so the entire heathcare vote hung on whether an accommodation on abortion language could be found that kept pro-life Democrats (many of them Catholic) on board. In the balance: the fate of health legislation sought by every Democratic president since Harry Truman (1944–1952), projected to expand coverage to some 32 million uninsured Americans, subsidize care for the poor and the working class, improve prescription drug benefits for the elderly, eliminate insurance industry practices widely seen as abusive, and do so while lowering federal deficits over the next 10 years [72,73].

However, also in the balance was a key goal of the American Catholic bishops for several decades: a health bill that would dramatically expand access to healthcare, while respecting other elements of Catholic teaching. Regarding the latter, recall that in addition to abortion and the “conscience clause”, the bishops had focused attention particularly on affordability and the rights of immigrants. The final bill was a mixed bag on these two concerns, effectively addressing affordability but barring undocumented immigrants from the new health insurance exchanges and leaving in place a five-year ban on even legal immigrants from Medicaid. However, as the final vote approached in mid-March 2010, the politics of it were clear: passage would dramatically expand affordability and empower those in Congress likely to support subsequent immigration reform, while defeat would empower those in Congress most opposed to the bishops on matters of immigration. What the health reform bill would do on abortion—that third rail of healthcare reform—was still open to interpretation and negotiation even in the days leading up to the final vote.

Here, public Catholicism spoke with several voices: the USCCB remained opposed to anything short of the Stupak language, and thus refused to endorse the final bill. If Catholic legislators and their allies adopted this position, it would effectively kill the reform effort, since there appeared to be no other way for the legislation to pass in the current Congress. However, other Catholic institutions weighed in as well. Three emerged most prominently in public discussions. First, the Catholic Health Association, which had argued throughout the debate for health reform meeting the three USCCB criteria, issued a statement implicitly endorsing the bill up for a vote [74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. Second, an organization named “NETWORK: A Catholic Social Justice Lobby” issued a strongly-worded endorsement signed by the Leadership Conference of Women Religious and the heads of more than 50 women’s religious orders that together include more than 95% of American nuns [81]. Third, Catholic public intellectuals also endorsed the final bill in explicitly Catholic terms, most prominently the Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne, Jr. [82]. As noted above, these voices of public Catholicism carry differing degrees of authority within the Church, with the bishops holding official authoritative power. However, in the public arena, this distinction is not so clear: public Catholicism spoke in a complex voice representing various views, all appealing to democratically elected congressional representatives on the basis of Catholic worldviews and commitments. It also seems likely that at least some portion of the bishops themselves were loathe to go down in history as having been central actors in killing healthcare reform; presumably, they were pleased that some Catholic voices provided cover for Catholic legislators wanting to support the bill.

Ultimately, it was those congressional representatives who had to vote for or against the final legislation. That vote came on the evening of 21 March 2010. At the insistence of the pro-life members of Congress led by Representative Stupak, President Obama agreed that afternoon to issue an executive order clarifying that the bill authorized no use of federal funds to pay for abortion. With this step, Stupak and several others agreed to support the final bill. That night the bill passed on a 219–212 vote, and was signed into law later that week [83,84,85,86].

Thus, health reform came to the United States after decades of failed efforts and intense debate over what precisely would constitute “reform”. That debate will continue, over implementation questions (such as the new law’s impact on abortion and how immigrants are to receive medical care in the new health marketplace) and over ethical questions (including the debate on the law’s impact on abortion). My purpose here is not to engage in those debates, but rather to analyze the dynamics of public Catholicism both within and beyond the great health reform debate of 2009–2010. Before doing so in depth, I note several features that seem clear from the foregoing analysis.

First, the “Catholic contribution” to the debate was both enormous and complex. The overall weight of public Catholicism clearly pushed in favor of substantial reform within strong ethical guidelines. The USCCB strongly and consistently spoke to Catholics and policymakers about the dimensions of health reform that the Church would support. The final issues in the debate were partly focused around key areas of Catholic concern, with Catholic voices very much “in the room,” itself a significant achievement. The diversity of Catholic voices in the legislative end game reflected with reasonable accuracy the complexity of the moral, fiscal, societal, and human implications of tinkering with the massive health sector—and the political complications that inevitably came into play when restructuring a huge sector of the American economy during an election year. Some Catholic leaders will praise the final result while others will criticize it as either too weak on abortion protections or too weak on universal coverage. However, it seems incontestable that Catholic voices rooted in authentically Catholic concerns and commitments—from the USCCB and individual bishops to grassroots organizations—significantly influenced the health reform debate.

Second, various Catholic actors skillfully used their institutional resources to shape the debate. Through USCCB press releases, conversations with policymakers, and requests that local parishes make announcements and distribute information at key moments of the debate, the bishops made their position clear and mobilized constituents in support of it. Significantly, they did so repeatedly over the course of nearly a year of focused debate. Similarly, the CHA and the women’s religious congregations utilized their networks to support reform and intervened at strategic moments to publicly buttress their allies in Congress—and, in the legislative end game, arguably created the crucial political space for Catholic legislators to support the final bill.

Third, together with its secular and religious allies, the PICO National Network brought into the public arena an effective set of faith-based voices from poor, working, and middle-class communities. Furthermore, those voices contributed powerfully to a successful pilot run at healthcare reform (the SCHIP re-authorization) and to moving comprehensive healthcare reform through the congressional process. PICO’s role reflects the Catholic connections of faith-based community organizing noted above, but also transcends them: the organization brought people into the public arena as citizens rooted in poor to middle-class communities and as people of a variety of faith traditions, not as sectarian Catholics. Yet PICO’s overall thrust (in favor of reform that significantly expanded health coverage and made it affordable for poor folks) clearly reflected the emphases of its core religious constituencies: Catholic as well as Jewish synagogues, and liberal to moderate Protestant, Unitarian, and African-American and Latino Pentecostal churches. In that sense, PICO’s work during much of the debate bridged between public Catholicism, the public voices of other religious traditions, and the democratic public arena.

Fourth, where the teachings of those core constituencies differed, PICO remained silent. The organization never endorsed or opposed a specific bill. Embracing the Catholic bishops’ final position would have alienated the organization’s liberal Protestant, Jewish, Unitarian, and some Pentecostal constituents. Rejecting that position would have alienated some of the organization’s Catholic constituents. Instead, in the final legislative push PICO encouraged its members to seek guidance in their own religious tradition’s statements on the topic. In this sense, although PICO represented a salient voice of Catholicism (and other faith traditions) through much of the debate, in the political end game that role fell to other figures and organizations.

Fifth, the various voices of public Catholicism, though largely united during most of the debate, differed acutely in their assessments of the final legislation. Although that diversity of public views contributed to final passage of health reform, it also reflected a certain incoherence in American Catholicism today. I suggest below that this incoherence is rooted in divergent understandings of authority and the nature of the Church—though not in the ways one might expect.

Finally, one must wonder how the health debate has re-shaped the overall impact of public Catholicism. Presumably, the experience deepened the reservoir of democratic skills, policy expertise, and public orientation at many of the levels of public Catholicism summarized in Figure 1 above. Additionally, high-profile involvement in this debate may have strengthened public Catholicism’s political capital for future policy debates. If that is the case, it was hard to discern in subsequent battles regarding immigration reform, though perhaps nothing could have overcome Tea Party intransigence on that terrain. Alternatively, the USCCB and Catholic bishops may have lost considerable political capital by staking their final position on healthcare reform on what some—including some figures within public Catholicism who appear to have been acting in good faith—regarded as a tendentious and perhaps partisan interpretation of the final healthcare bill. Only ongoing political events will make clear which has actually occurred, but one fairly immediate way to gauge this lies in these events’ impact on figures of “public Catholicism” within Congress. Initial signs included Bart Stupak’s decision not to seek re-election, the result of his demonization by pro-life political forces, despite his having gone to bat repeatedly for pro-life provisions in the healthcare bill. One interpretation: the bishops’ ultimate position on healthcare reform—portrayed by some as intransigent and by others as prophetic—made it impossible for their own allies to navigate the complex cross-currents of public life and remain viable for public office. The bishops’ stance simply offered no cover for their own allies to make the prudential judgments and political compromises that are inevitable in a democratic public arena. Thus, while the overall Catholic influence in the healthcare debate (from the USCCB and other voices) certainly appears to have strengthened the strategic position of public Catholicism, the bishops’ failure to provide their allies with public room to maneuver appears to have weakened the position of public Catholicism—and perhaps that of the bishops themselves [87].

However, the healthcare debate can only show us so much; to gain greater perspective, I step back from that specific debate to examine broadly the dynamics of public Catholicism in America today.

5. Analyzing Institutional and Cultural Dynamics

Analyzing three additional institutional and cultural arenas will offer further insight into the nature of Catholicism within American public life. These arenas are leadership in mediating institutions; authority dynamics; and the culture of worship, prayer, and spirituality.

5.1. Institutional Leadership

Catholicism has a rich intellectual tradition of thinking broadly about how laypeople contribute to public life via leadership in civil and political institutions. Separately, whole subfields of social science and organizational management analyze the roles of institutions and organizations in shaping society, especially through what sociologists have long called “mediating institutions” or “voluntary associations”. Here, I note only a few insights important for thinking about public Catholicism.

In the future, public Catholicism will be influential to the extent that it: (a) at the level of national politics decisively leaves behind a model whereby the bishops or the USCCB strive to unilaterally define truth; (b) at the level of political society advocates for those Catholic ideals for which a democratic consensus or working coalition can be built; and (c) at the level of civil society lays the cultural foundations for future coalitions by mediating into American culture a more intense encounter between mainstream culture and those Catholic ideals that now stand outside it. In the latter encounter, Catholicism will have to challenge contemporary consumerism’s idolization of individual autonomy. That task is made more complex by the fact that Catholicism—despite its fundamental commitment to a pro-social and communitarian vision of the human person [88,89]—has itself been affected by the idolization of individual autonomy, with the attendant rise of heterodox expressions of Catholicism committed to economic libertarianism, including within Congress. To be a fully credible interlocutor at all these levels of a democratic and rights-affirming public arena, public Catholicism must clearly signal its affirmation of modern standards of personal rights and democratic norms—not a simple task due to remaining vestiges of pre-modern Catholicism at times still influential within the Church. Pope Francis appears committed to eliminating the influence of both heterodox economic libertarianism and pre-modern traditionalism, but it is too early to judge whether he will succeed at either.

Crucial for shaping public Catholicism’s future will be the presence of engaged Catholics as leaders of mediating institutions at all levels of society, from local non-profits to national civil associations, from neighborhood associations to state political parties to Congress, from school teachers to international scholarly associations, and from family businesses to major corporations (i.e., the middle level of Figure 1). Such leadership roles in differentiated institutional sectors are too myriad to discuss coherently as a group here, much less to coordinate nationally through some national Catholic structure. Nor would such central coordination be desirable, as it would almost surely be too rigid and authoritarian to be acceptable in a democratic public arena. Rather, public Catholicism will be coordinated via Catholic teaching and inspiration and via citizens’ discernment in democratic dialogue with the wider culture. Catholics already occupy many leadership roles in which this occurs, and more will do so in the future as Latino Catholics, in particular, move into higher-level leadership in American society. Catholics in positions of institutional leadership can serve as bridges between the Catholic tradition and American institutional life, to the extent that they are deeply immersed in the former and capable of bringing their resulting worldview insightfully to bear within secular institutions, inspired and informed by the teaching role of the bishops but also by American democratic ideals.

The efficacy of lay Catholic leaders in this bridging role will be shaped crucially by higher education. In one sense, there is nothing new in this: for generations, Catholic leaders have sought to use universities to train laypeople for leadership in the secular world, and the Second Vatican Council reaffirmed the centrality of this dimension of lay vocations in Gaudium et Spes. However, two recent shifts make this yet more central. First, as educational levels have risen throughout American society, a university degree followed by postgraduate studies or professional credentialing has become the gateway to institutional leadership in most sectors of society. Second, as Catholic lay leaders have attained higher levels of education and embraced democratic and professional sources of authority, they expect a more consultative relationship with the Church hierarchy. As illustrated by the health reform debate, educated laypeople who exert autonomous authority in mediating institutions simply will not respond to the assertion of a central command-and-control model of clerical or episcopal authority. The days of that model of American public Catholicism are likely gone forever, at least as long as the United States remains an educated and democratic republic.

The most crucial mediating institutions for shaping public Catholic leaders of the future will be universities, both Catholic and public. Catholic universities obviously matter, since they most directly embody and teach Catholic ideals, however imperfectly. Public universities and their attached Catholic ministries will be at least as crucial—and perhaps more so: in purely demographic terms public universities simply touch the lives of huge numbers of young Catholics, especially from the less-privileged sectors that Catholic social teaching seeks to make central agents of social transformation. In addition, public university settings incorporate important parallels to the situation that will be faced later in life by Catholic lay leaders of secular institutions: in both settings, Catholic leaders take the values and social commitments learned from their tradition and bring them to bear within more pluralistic and secular settings. Bridging successfully across that institutional divide is a learned skill, and public universities with strong Catholic campus ministries offer students experience in precisely that kind of cross-institutional engagement.

5.2. Authority Dynamics: Church and Sect in American Catholicism