1. Introduction: Conflicts of Rhetoric and Rhetorics of Conflict

On Friday, 13 October 2006, Eduardo Zaplana made an announcement that—on the surface, at least—would seem relatively straightforward and cause for excitement and even celebration. In his role as official spokesman for the Popular Party (PP), one of Spain’s two main political organizations, Zaplana announced that the PP would present a non-binding resolution (proposición no de ley) in the Congress of Deputies (el Congreso de Diputados), the nation’s lower legislative house, supporting the candidacy of a class of regional festivals for international recognition as an indispensible part of “human patrimony.” Zaplana explained the specifics of his party’s initiative as well as its timing. The PP wanted clear congressional support for Spain’s application to the United Nations Educational, Science, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to inscribe a number of new elements on UNESCO’s list of “Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.” As Zaplana emphasized, the inclusion of these particular fiestas (festivals) on the list of candidates made perfect sense at that moment. Some European organizations had recently declared the celebrations a matter of “international tourist interest” and on the preceding Monday (9 October)—only four days earlier—prominent representatives of the fiestas had participated as honored guests in the Hispanic Heritage and Columbus Day Parade in New York. Fittingly, as Zaplana pointed out, the special Spanish emissaries carried out some of the celebrated traditions as they marched down Manhattan’s famed Fifth Avenue, only blocks away from the UN headquarters where the world-heritage application would be filed. Using his well-honed skills as a political spokesman, Zaplana made his best effort to give the announcement a festive air. What could be better than celebrating renowned celebrations, than feting famous festivals, than securing them the global recognition they deserved? Zaplana wondered openly how anyone could possibly object to the proposition.

However, in raising that question, Zaplana implicitly acknowledged that there were people who

did oppose the Popular Party’s plan. In fact, beyond his scripted announcement, Zaplana spent most of the 13 October press conference framing his party’s initiative as a deliberate counterattack. In other words, he made clear that the PP’s declaration of intentions served as the latest retort in a broader political battle that had intensified during the week leading up to the announcement and in which the traditions lauded by the Popular Party served as the immediate object of dispute. The celebrations that the PP planned to bring to the Congress for validation were

Las Fiestas de Moros y Cristianos—the Festivals of Moors and Christians—especially popular on or near the Mediterranean coast in the southern part of the Valencia region in Spain’s east. Even before the developments leading up to Zaplana’s announcement, the

fiestas generated periodic controversy. And, in that regard, the October 2006 debates followed a familiar script. Because the festivals invoke the so-called “Reconquest” of Iberia by Christian forces from Islamic powers, pockets of critics regularly decried the celebrations as symbolically violent and thus offensive, especially to contemporary Muslims. In the late 1990s, public condemnations of the festivals from various quarters began to grow louder and more frequent in conjunction with the increased size and visibility of the nation’s population of Muslims from immigration and other factors

1. In light of the growing presence of Islam in Spain, did the Popular Party really want Congress—much less the United Nations—to sanctify these potentially offensive celebrations as the apex of Spain’s cultural contribution to humanity? Or, in fact, was the Popular Party’s move a direct reaction to the nation’s changing demographics, an attempt to secure global recognition for collective identities supposedly on the wane?

In his 13 October press conference, Zaplana did not address either of those possibilities but instead tried to shift attention away from questions regarding the role of Muslims and Islam in Spain’s changing social realities. He attempted to present his adversaries as the problem, painting them as threats to the collective spirit engendered in the festivals as well as impediments to the

fiestas’ economic and civic benefits: “Under no circumstances will we address the demands of those who try to coerce us. We feel very proud of these

fiestas, of this tradition, of this spontaneous demonstration that we live so intensely and of the great splendor they manifest—and which is so important for the development of our tourist sector.” Zaplana also made clear that the Popular Party’s proposed resolution amounted to a counter-offensive against the ongoing criticisms of the Moors and Christians celebrations, insisting that the effort thwarted “a distinct threat to the liberty of expression, a self-censorship, [that] is spreading” [

5,

6]. The debates about the festivals continued throughout October in the halls of government, in the press, among families, friends, and neighbors, and in other domains of public discourse. The intensity of the discussions died down over the months that followed, flaring up every few weeks as the press reported on new moves or statements in the political chess-match, until February. That month the Popular Party presented the non-binding resolution on the

fiestas’ candidacy to Congress as promised, and when the effort failed to pass the battle effectively ended.

Although the disputes beginning in October 2006 about the Moors and Christians festivals followed a familiar pattern—and turned out to be relatively short-lived—the context of the debates nevertheless differed from the past. That environment—the particular landscape of the conflict—serves as the focus of this essay. The oppositional language with which I have outlined the topography of events clarifies the first meaning of the title of this essay. Most immediately, I outline here the war of words—the wrangling through rhetoric—that entangled the festivals at the time. In doing so, another connotation of the title quickly arises: Not only did the debates about the Moors and Christians festivals amount to rhetorical conflicts; the controversy also unfolded around a public discourse centered on notions of geopolitical contestation. More specifically, “civilizational” rhetoric—consistent with Samuel Huntington’s famous thesis about a post-Cold War “clash of civilizations”—resonated deeply. With the arrival of the fifth anniversary of the events of 11 September, 2001 and only two-and-a-half years after deadly bombings on commuter trains outside of Madrid, considerations in Spain—as elsewhere in Europe and across the Atlantic—swirled around the figure of “Islam” and questions about its fundamental nature and the extent of its reach. Despite important and deep differences of opinion, the collective conversation in Spain advanced on a common ground where “Islam” and “the West” represented two distinct and oppositional entities vying for global power.

In this regard, the dispute in late 2006 over the candidacy of the festivals for “human patrimony” designation serves as only part of a longer series of skirmishes in Spain’s ongoing culture wars. The public disagreements about the fiestas that erupted during the first week of October 2006 only made more immediate and contextual a broader set of national, continental, and global issues with which Spaniards already had grappled for almost a month. As I explore in detail below, the conflicts over the Moors and Christians celebrations make sense in light of the worldwide debates generated by Pope Benedict XVI’s reflections on characteristics of Islam during an academic talk delivered the preceding 12 September. Those issues took on new shape and intensity eleven days later when, during a talk in Washington, DC, Spain’s former prime minister, José María Aznar, added to the uproar by following up on the pontiff’s speech with his own comments about the role of Islam in the contemporary world as well as in Spanish history. In a peninsula long characterized by diverse and often competing claims of affiliation—be they individual or collective, national or regional, continental or global, religious or secular, to identify only a number of possibilities—the status of “Moors” and “Christians” cut to the heart of apprehensions both historical and contemporary. Accordingly, the rhetoric of “civilizational clash” that framed the public discourse in Spain in late 2006 exposed underlying anxieties regarding issues of immigration and national security. As I show, those pressing concerns exposed fundamental questions of identity and—in a broader sense—of “patrimony.”

In that way, the essay’s title carries yet-another implication. While the debates played out around a discourse of “culture clash,” the fiestas themselves present “rhetorical conflicts,” that is, mock performances of past battles between “Moors” and “Christians” as distinct “civilizations” sparring for control of the territory. The rhetoric about the festivals in 2006 paradoxically mimicked the traditional rhetoric of the festivals. And, at that level, the essay’s title encapsulates another dynamic: While the notion of culture clash predominates in and provides the structure of the fiestas, the celebrations also include an obvious counterpoint. At a number of points in the performances—and, especially at their climatic moments—the identities of the “Moors” and “Christians” quickly shift and the divisions between them break down. At those junctures, different rhetorics—one of clear separation, the other of equivocality and hybridity—come into dramatic conflict. In the concluding section of the essay, I look closely at one of those critical junctures to show how, in the end, the festive performances call into question familiar claims of identity and of patrimony and, in turn, unsettle Samuel Huntington’s “culture clash” thesis in particular and civilizational discourse in general. Accordingly, the festivals, as well as the debates about them, illuminate the profound and ongoing anxieties among Spaniards about the place of the proverbial “Moor” in Spanish history and identity and how those competing sensibilities relate to the social locations—that is, the very real presence—in contemporary Spain of residents still firmly linked in the popular imagination to that Moorish past.

2. Moors and Christians on the Rhetorical Battleground: The Politics of “Human Patrimony”

In his press conference on 13 October 2006 explaining the Popular Party’s intentions to bring the non-binding resolution to the Congress of Deputies in support of inclusion of the Moors and Christians festivals on UNESCO’s list of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, Eduardo Zaplana framed the announcement as a necessary political response to recent criticisms of the fiestas. His characterization surprised some observers for two reasons. First, “world heritage” initiatives traditionally developed in Spain through the coordinated efforts of government agencies and local organizations. Political parties did not claim responsibility for instigating such efforts. So why did Zaplana, as the PP spokesman, declare his party would assume that role in this case?

The PP’s unprecedented endeavor generated the second point of surprise. Why was the PP pushing for a new legislative measure when, in fact, the drive to secure UNESCO recognition of the Moors and Christians celebrations already had been underway for at least two years? In June of 2004, La Unión Nacional de Entidades Festeras [The National Union of Festival Entities]—commonly known by the acronym UNDEF—announced the organization’s commitment “to initiate the opportune labors to secure the declaration of the

fiestas de Moros y Cristianos as oral and immaterial patrimony of humanity by UNESCO” [

7]. At that time UNDEF also announced the chairs of the commission that would lead the effort: Francisco López Pérez, the newly elected president of UNDEF, and Pedro Escrig Negrete, head of the Association of Moors and Christians Santa Marta of Villajoyosa, a town in the province of Alicante.

The commission, led by its two coordinators, subsequently spent the following years in active pursuit of UNDEF’s declared goal. The group did so in the expected and familiar manner, working closely with governmental agencies and U.N. deputies to develop a case and to navigate the application process. As October of 2006 arrived, the commission pointed to a tangible result of their months and months of hard work: some outstanding representatives of the Moors and Christians festivals—a selection from the Alicante town of Alcoy’s neighborhood associations—had been invited to march in New York’s Hispanic Heritage and Columbus Day Parade [

8]. UNDEF and others considered the invitation an encouraging sign that UNESCO eventually would recognize the

fiestas with the “human patrimony” designation.

Like many others, the members of UNDEF also understood that—should the campaign achieve its goal—the achievement would culminate a process that began in earnest in the 1990s. During that decade, Spain joined a number of other nations with formal initiatives to establish national and international mechanisms for celebrating and protecting important—and potentially vulnerable—forms and sites of cultural expression. In fact, the Spanish government played a critical role leading to the Proclamation of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO’s Director-General in 2001, successfully presenting the Mystery Play of Elche that year as one of the first candidates for recognition [

9,

10]. At the same time, the government initiated the recognition process for another popular rite—the famous “Patum” commemoration held in the Catalan town of Berga during Corpus Cristi observances—that finally earned formal “masterpiece” status in 2005.

More broadly, Spanish diplomats spearheaded efforts to expand and to systematize “intangible heritage” mechanisms at both the domestic and international levels. Spain’s delegation was instrumental in UNESCO’s 2003 draft of a Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage [

11]. The Convention provided both an international structure and financial support for preservation of key elements of “living culture.” In advance of the Convention’s anticipated approval by member states and its assumption of force, the government encouraged entities around Spain to nominate candidates for UNESCO recognition. After more than two years of public discussion and consideration and with the inauguration of the Convention on schedule, the government headed into the fall of 2006 confident that UNESCO would approve its first slate of proposed elements under the new pact. Representatives of the Popular Party proclaimed that, with the presentation of its nominees at the major upcoming meeting at the United Nations’ headquarters, the time had come to enjoy the fruits of a sustained campaign and, most importantly, to revel in international recognition of Spain’s illustrious contributions. Among all the world’s nations only Italy had more “world heritage” elements than Spain, and now a significant collection of oral and intangible “masterpieces” would add to that long, internationally recognized list of the nation’s outstanding “human patrimony”.

This brief review of the development of the international “intangible heritage” movement—and of the particular location of the Moors and Christians festivals within that history—clarifies the reasons why the Popular Party’s announcement on 13 October 2006 caused surprise and also why the PP would make that move. Simply put, “world heritage” designations depend on a complex, often tense process carried out across various arenas of domestic and international politics. Much is at stake in those labels as well as for those who get credit for their success

2. They generate much more than national pride. As almost anybody in Spain—and especially any deputy in its government—understands, U.N. recognition of “World Heritage” sites—like the Great Mosque of Córdoba, Granada’s Alhambra, the Royal Palace and Monastery at El Escorial, or Barcelona’s Gaudi-designed Parc Güell and Casa Milà—brings substantial economic benefits, including international financial support and status-inspired tourism.

Eduardo Zaplana—and the political organization for which he spoke—clearly understood these high stakes when he announced the Popular Party’s unexpected attempt to carry the issue of the “human patrimony” of the Moors and Christians festivals through the doors of the Congress of Deputies and, thus, to politicize the issue explicitly. But why would the Popular Party make that move when it did, presenting these fiestas—out of all the possibilities—as the lightning rod? As Zaplana and the PP also knew, UNESCO and the wider spheres of international diplomacy can serve too as frontlines in the culture wars. The time and place were right to pick up the fight, it seemed. But, in order to understand why, we need to consider first the unique character of the object of conflict, that is, of a unique class of festivals that, curiously, dramatize their own version of “culture wars.”

3. The Rhetorical Battlegrounds of Moors and Christians

While popular studies of the Moors and Christians festivals—including frequents exposés by travel writers and for the benefit of tourists—are extensive, scholarly analysis is more limited

3. Yet, even a cursory review of this body of literature quickly exposes the cluster of tensions that define the festivals. For example, Moors and Christians celebrations take place throughout much of Spain as well as in areas around the world that belonged to the vast Spanish empire, and the widespread celebrations lay claim to a common format comprising a long-running, far-reaching tradition

4. At the same time, each site presents an independent and dynamic iteration of the festival ostensibly based on an exclusive, local history. In every case, the festivals center on a stylized series of battles that adhere to a set structure. Over the course of the festival (usually four to seven days), members of the community re-enact a historical drama defined by a few key plot points. First, a powerful army of “Moors” invades and takes possession of the area, typically marked by the capture of and raising of their flag at the town’s main “fortress.”

5. Over the ensuing days of the celebration, a steely and overmatched band of “Christians” face long odds and temporary setbacks, yet eventually defeat and expel the Moorish “occupiers,” restoring both land and culture into the fold of Christendom (see

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 [

27,

28,

29,

30]). In other words, each festival re-enacts—in a compressed and schematic form—the so-called

Reconquista, or “Reconquest,” of Iberia ostensibly completed in 1492. On January 2 of that year Ferdinand and Isabella, Spain’s venerated “Catholic Monarchs,” secured the takeover of Granada (the peninsula’s only remaining Islamic emirate) and, a few months later, issued the Edict of Expulsion requiring all Jews to leave the monarchs’ territories by the end of July.

While the common narrative that structures each of the Festivals of Moors and Christians is basic—Moorish invasion followed by the Christians’ eventual recovery—the celebrations are, invariably, far from simple. In fact, complexity of detail—or, more precisely, comprehensive spectacularity—functions as the essential characteristic of the festivals, regardless of its scale or duration. The process of amplification begins with the founding historical narratives themselves. As noted earlier, the heaviest concentration of festivals, including the largest and most renowned observances, lies along the coast and in the near-interior of Alicante, Valencia’s southernmost province (

Figure 5 [

31]). Many towns and neighborhoods in and around Alicante city, the provincial capital, also hold celebrations. In each case, the “host” area—whether town, village, or neighborhood—presents and explains the historical events that serve as the basis for their particular observance. For example, in the town of Alcoy—the site of the largest festivals and the source of the 2006 Columbus Day Manhattan marchers—participants link the celebrations to a battle in April 1276. According to local legend, St. George (commonly known in Spanish as “Matamoros,” that is, “Moor Killer”) enabled the decisive victory of Christian forces over a powerful Moor army. Thus, Alcoyanos observe their

Fiesta de Moros y Cristianos in conjunction with St. George’s April feast day. Similarly, Villajoyosa—a village not far south of Alcoy along Alicante’s coast and site of another of the most famous festivals—holds its celebrations in July around the Feast of St. Martha, who supposedly came to the miraculous aid of the Christian community in 1538 to repel a Barbary naval assault on the village.

These historiographic justifications often comprise intricate chronicles constructed, preserved and perpetuated by an association of local societies

6. The network of groups organizes into distinct units, each with its own identity and shield and known alternately as

embajadas (embassies),

cuarteles (barracks or platoons), or

escuadras (squadrons) (see

Figure 6 [

33]). In this way, a complex institutional network in each town, village, or neighborhood prepares at length for and then carries out its celebration at a different time—usually during the spring or summer and often in conjunction with the feast day of a particular Catholic saint—and in correlation with distinct historical episodes over the centuries of “the Reconquest.” In some places, a unit plays the same role each year but, in many cases, the groups alternate jobs and identities, playing a “Christian” part one year and then appearing as “Moors”—often in blackface (

Figure 1)—the next. In addition to the military re-creations—which can involve full caravels arriving by sea (

Figure 2) and armies storming a town’s medieval castle (

Figure 3)—the multi-day celebrations include festive parades of the regiments of “Christians” and “Moors” and impressive firework displays to mark the heroic accomplishments of each army, especially of the “Christians’” final triumph (

Figure 4). The costumes and props are extravagant, expensive, and evocative.

Figure 1.

A squadron of Moors enters the city. Town of El Campello, Alicante province, 2006.

Figure 1.

A squadron of Moors enters the city. Town of El Campello, Alicante province, 2006.

Photo by Bereber. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons [

27].

Figure 2.

The Moors “disembark”. Town of Villajoyosa, Alicante province.

Figure 2.

The Moors “disembark”. Town of Villajoyosa, Alicante province.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons [

28].

Figure 3.

The battle for the castle. Town of Petrer, Alicante province.

Figure 3.

The battle for the castle. Town of Petrer, Alicante province.

Image provided by Fiestas de Moros y Cristianos [

29].

Figure 4.

The “Basque Christians” advance, seeking “reconquest”. Town of Alcoy, Alicante province, 2006.

Figure 4.

The “Basque Christians” advance, seeking “reconquest”. Town of Alcoy, Alicante province, 2006.

Photo by Popezz. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons [

30].

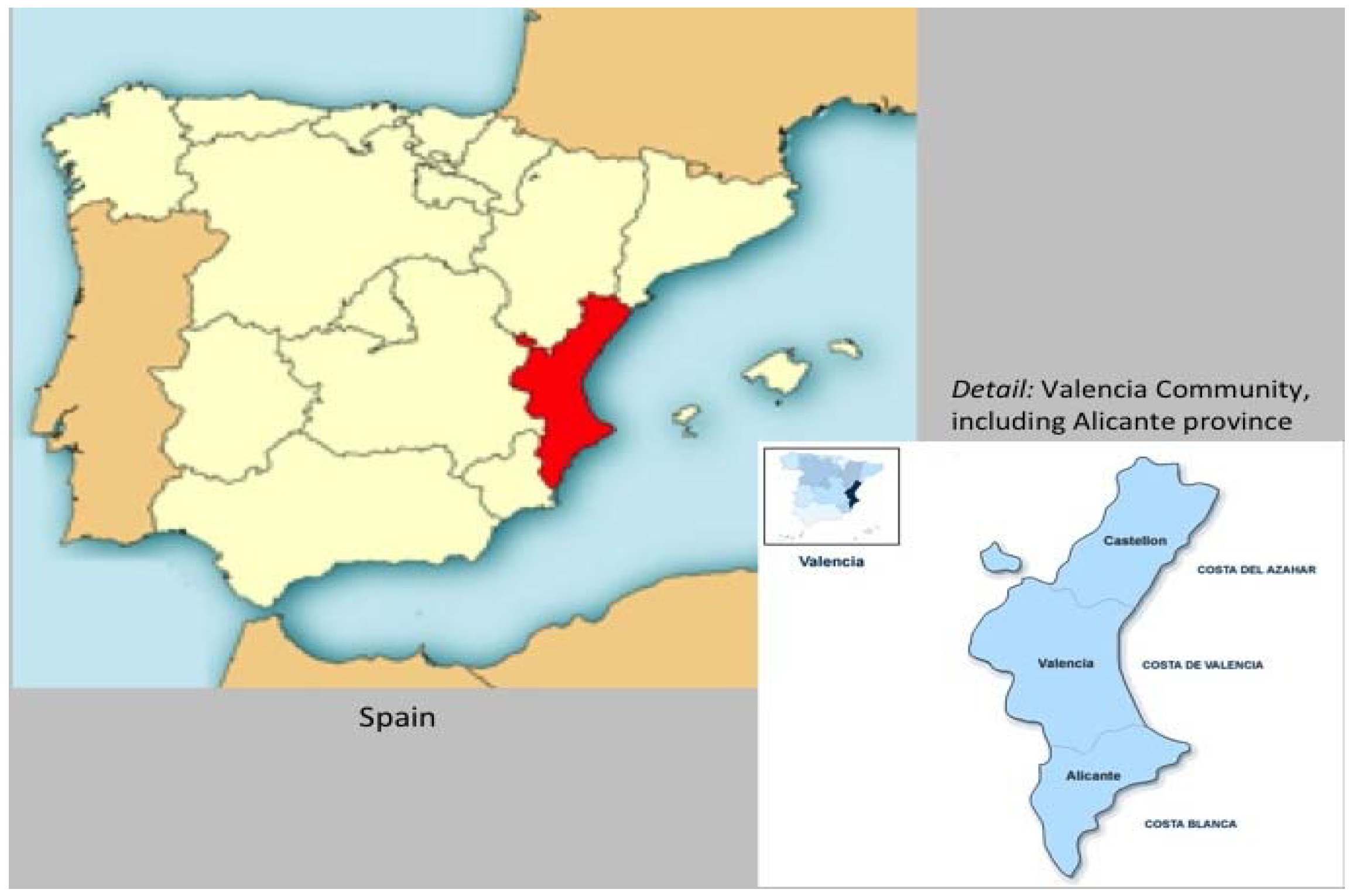

Figure 5.

The domain of Moors and Christians: Alicante province, Valencia Community, Spain.

Figure 5.

The domain of Moors and Christians: Alicante province, Valencia Community, Spain.

Note: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons [

31].

Figure 6.

Sample of shields of association “squadrons” from San Blas neighborhood, city of Alicante.

Figure 6.

Sample of shields of association “squadrons” from San Blas neighborhood, city of Alicante.

Images provided Asociación de Moros y Cristianos de San Blas [

33].

However, these invocations and re-enactments of historical events expose a central tension in the festivals between socio-historical ideals and realities. Most immediately, the

fiestas summon “the Reconquest” as a clear—albeit powerful—overarching narrative: The Christian heroes bring Spain out of the Middle Ages and into the modern epoch by restoring the peninsula to its unified and rightful cultural identity after prolonged and oppressive fragmentation under the grip of invading Moors. Yet, at the same time, every version of the festival claims a singular chapter in this broad history. This appeal to historical particularity offers an implicit reminder that “the Reconquest” was not a simple, cohesive, or even linear march to the reunification of Iberia under the banner of Christianity after a long and shameful “interlude” under Islamic Moorish power. The historical realities were much more complex, such that many of the conflicts during the centuries leading up to (and even occurring after) 1492 and now celebrated as part of the teleology of “reconquest” actually involved Christians fighting Christians and/or Muslims fighting Muslims

7. For instance, archival evidence suggests that the occasion for St. George’s extraordinary intercession in April 1276 and the source of Alcoy’s festive commemoration each year in fact played out as something quite different than a showdown between “Moors” and “Christians.”

8. The conflict apparently arose as an episode in the fierce rivalry at the time between the two Christian-led kingdoms of Aragon and Castille ([

18], p. 236). Similarly, Ferdinand and Isabella’s “defeat” of Granada—typically heralded as the crowning event of “the Reconquest”—ultimately unfolded not as a military victory but rather as Emir Muhammad XII’s handoff of control to “the Catholic Monarchs” after months under siege and in the face of potentially worse prospects at the hands of the Muslim Marinids from northern Africa.

Precisely because of such disparities between the archetypal narrative summoned by the Moors and Christians festivals and their underlying historical actualities, the

fiestas function as what David Guss identifies as “semiotic battlefields” ([

35], p. 10). The audience and actors—all participants in the shared public performances—find diverse, often divergent meanings in them. The representational mechanism of the festivals—the stories, the symbols, and so forth—‘say’ and ‘do’ different things for different people. In the concluding section of this essay I explore in greater depth the points of friction at work in the celebrations. As I show there, the tensions arise not only from the play between schematic invocations of “the Reconquest” and complex, local histories or from competing understandings of the

fiestas among participants. Rather, the Moors and Christians observances ultimately publicize and attempt to sublimate the various cultural elements on which modern Iberian identities are founded. In other words, the festivals convey a critical subtext that inherently complicates the bipartite schema of “Moor versus Christian” and the narrative of territorial and cultural reunification that predominates. After all, the maneuvers carried out on the

fiestas’ “semiotic battlefields” are more intricate than they initially appear.

Nevertheless, as Guss reminds us in delineating conflicting forces at work in certain twentieth-century Venezuelan celebrations, surface appearances matter tremendously in the festive realm. Popular festivals operate with the immediate purpose of conveying and reinforcing specific ideals, even if those principles begin to unsettle upon closer examination or from competing perspectives. Whether employed deliberately or not, public festivities serve as strategic elements in the inevitable politics of culture. The human patrimony debates that arose around the Moors and Christians celebrations indicates the extent to which the cultural politics embedded in this particular set of festivals connects directly with Spain’s long-running tradition of struggles over historical memory. How is the past represented? Where, and by whom? Those questions have led especially to recurring public tussles about conceptions of Iberia’s medieval past

9.

Indeed, as Max Harris explains in his comprehensive account of the parallel development of Moors and Christians observances in Spain and in Mexico, the festivals probably originated in the late 1500s at the instigation of King Felipe (Philip) II, who famously revised and promoted a variety of traditional celebrations in order to assert Spain’s imperial glory ([

26], p. 46). When local militias responsible for protecting the coast of Valencia against the Turkish navy and Barbary pirates began to enact mock battles, the king recognized the opportunity to formalize the practice in festive public dramatizations of his forces’ victories. Thus was born the tradition of popular

fiestas centered on re-enactment of heroic “Christian reconquest” against formidable “Moor” occupiers.

The origins of the festivals more than four centuries ago as instruments of imperial propaganda provide an important reminder of the ostensible function of current versions of the celebrations. While they no longer serve to mythologize Felipe II’s empire, the

fiestas still explicitly present and support specific myths about Spanish history and its role in shaping national and regional identities

10. Similarly, the festivals’ emergence from the machinations of a “Golden Age” monarch also underscores the specific stagecraft on which the celebrations—then, as now—have always depended in depicting their respective mythologies. In that regard, the Festivals of Moors and Christians have always been decidedly and purposefully carnivalesque. In all of their individual variations and claims to singular historical episodes, the

fiestas follow a skeletal structure that is fleshed out in intricate terms in almost every aspect of the festival. As José Luis Bernabeau Rico demonstrates in his pioneering study of the Moors and Christians commemorations, the festivals follow in the grand tradition of the

carnavales (carnival celebrations) by constructing parallel universes of time and space where participants might transcend—and ultimately, transform—familiar dimensions of everyday life [

19]. At the very least, the celebrations unfold along the lines of what Roland Barthes, in his famous diagnosis of the world of professional wrestling, calls “spectacles of excess.” In self-contained arenas, bombastic gestures, symbols, and material accouterments reinforce particular “mythologies” in the clearest and most visceral terms [

41]. Similarly, the unrelenting grandiloquence of the Moors and Christians festivals proffer and reinforce the idea of the Christians’ triumph—and, thus, the historical process of “reconquest” and territorial reclamation—as inevitable, even divinely sanctioned. At every turn Moors and Christians appear, in excessive terms, as polar opposites. Undoubtedly, the

fiestas operate as rhetorical conflicts, that is, as mock battles and dramatized showdowns between two distinct cultural entities. Was it a strange twist of fate, then, that when the festivals were drawn into other sorts of rhetorical conflicts—wars of words in the political sphere—in the fall of 2006 that the public skirmishes played out, like Moors and Christians celebrations themselves, in terms of a “clash of civilizations”? Whatever the causes for the curious convergence of these various rhetorics of conflict, we need to turn our attention back to the contexts of those debates and the discursive framework in which they played out.

4. “Marching Under New but Often Old Flags”: Huntington on “The Clash of Civilizations”

As 2006 moved toward its conclusion, notions of profound culture clash circulated not only in the Festivals of Moors and Christians but also in public discussion on all sides, and that reality brings me to some of the central concerns of this special issue of Religions and of this essay. Twenty years after its initial proposition, Samuel Huntington’s controversial thesis regarding “the clash of civilizations” still holds influence, particularly as it has impacted not only collective discussions about but also public and private actions regarding Islam and Muslims in Europe and North America. The 2006 debates about the Moors and Christians festivals demonstrate the enduring legacy of the “civilizational” approach.

In a now-familiar set of developments, Huntington first floated the idea—in the form of a question—in “The Clash of Civilizations?”, an article published in the summer 1993 issue of the journal

Foreign Affairs [

42]. Since the article “stirred up more discussion in three years than any other article they had published since the 1940” (according to the journal’s editors), Huntington offered a self-described “fuller, deeper, and more thoroughly documented answer to the article’s question” in a 1996 book framed with a now-declarative instead of interrogative title:

The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order [

43]. Despite the substantially more detailed presentation, Huntington’s main premises in the book remained the same as in the original piece. Writing in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union, Huntington observed that the end of the Cold War engendered:

the beginnings of dramatic changes in peoples’ identities and the symbols of those identities. Global politics began to be reconfigured along cultural lines. […] In the post-Cold War world flags count and so do other symbols of cultural identity, including crosses, crescents and even head coverings, because culture counts, and cultural identity is what is most meaningful to most people. People are discovering new but often old identities and marching under new but often old flags which lead to wars with new but often old enemies.

Based on this analysis, Huntington concluded that “the post-Cold War world is a world of seven or eight major civilizations. […] The key issues on the international agenda involve differences among civilizations. Power is shifting from the long predominant West to non-Western civilizations. Global politics has become multipolar and multicivilizational” ([

43], p. 29). Huntington proceeded to delineate nine “major civilizations” (despite his reference to a “world of seven or eight”): “Western, Latin American, African, Islamic, Sinic, Hindu, Orthodox, Buddhist, and Japanese” ([

43], pp. 26–27). The list already belies his sense of the fundamental role of religion in defining “culture and cultural identities, which at the broadest level are civilizational identities” ([

43], p. 20). He highlighted that, even in the “multipolar and multicivilizational” configuration of the new world order, a broadly “religious” division between the Christian-based “West” and “Islam” would continue to deepen as a primary fault line in global affairs.

If Huntington’s paradigm generated widespread debate in 1993 and the years following, those discussions now look like mild compared to the interest in his self-described “civilizational approach” almost a decade after. Following the events of 11 September 2001, 11 March 2004 and other acts of terrorism, commentators on both sides of the Atlantic and in many spheres of public discourse praised Huntington as prescient and adopted the “civilizational” perspective as an explanatory model for a variety of developments. Still, in all of its iterations and adaptions, proponents built on Huntington’s basic assumptions: most immediately, that “the West” and “Islam” represent distinct historical formations guided by fundamentally different—and irresoluble—worldviews currently engaged in a “clash of civilizations” and, in turn, that such “clashes of civilizations are the greatest threat to world peace” and must be diffused by some means or another ([

43], p. 321).

5. Igniting a Rhetorical Fire: Pope Benedict at Regensburg

Five years after 11 September, 2001, civilizational rhetoric continued to resonate deeply on both sides of the Atlantic. The year began with ongoing and sometimes-deadly protests over cartoon depictions of Muhammad in Denmark’s leading newspaper, and the year included a number of other serious episodes stemming from controversial representations of Islam. As 2006 extended into September, many people took the year’s developments as clear evidence that a “clash of civilizations” indeed was underway. In a show of respect—but also certainly out of fear for potential backlash—many municipalities in Spain already had altered festive traditions in the wake of the Danish cartoon controversy [

44]. Still, in the days commemorating the fifth anniversary of the traumatic events of September 11, the words of one of the world’s most visible figures amplified the idiom of “culture clash”—whether by chance or by design—and set in motion the debates that would flare up in Spain the next month over the Moors and Christians celebrations. The sequence began in earnest on September 12 in Regensburg, Germany. It was there and then that Pope Benedict XVI—in the course of a five-day tour of his home country—delivered a talk entitled “Faith, Reason, and the University: Memories and Reflections” to a gathering of eminent “representatives of science”

11. In the now-famous speech, the Pope argued that the pursuit of truth and knowledge—the modern university’s most fundamental task—must proceed from two foundational and mutually constitutive standpoints, namely, reason and faith. Benedict introduced this argument by framing his remarks as a response to his recent encounter with a modern edition of a late-fourteenth-century text—

Twenty-Six Dialogues with a Persian (c. 1399)—by the Christian emperor Manuel II Paleologus (1350–1425? C. E.). The Pope used the text as a point of entry into more general reflection on the fundamental historical and philosophical differences between Christianity and Islam and, ultimately, as a means of outlining a mode of rationality that “listen[s] to the great experiences and insights of the religious traditions of humanity, and those of the Christian faith in particular.” To that end, Benedict completed his speech by circling back to Manuel II’s manuscript and by letting the Byzantine emperor—in his effort to bridge a seemingly inherent divide between Christianity and Islam—have the final word. He cited Manuel’s insistence that God, by nature, calls us to “act reasonably.” “It is to this great

logos, to this breadth of reason,” Benedict concluded, “that we invite our partners in the dialogue of cultures. To rediscover it constantly is the great task of the university” [

45].

Despite the pontiff’s final invocation of a “dialogue of cultures,” it was Benedict’s initial discussion of Manuel II’s text that garnered widespread attention and incited a global controversy. In setting his agenda, the Pope explained that he “would like to discuss only one point—itself rather marginal to [

Twenty-Six Dialogues with a Persian] as a whole”—and turned his attention to the seventh of the twenty-six “conversations” between (according to Benedict’s own characterization) “the erudite Byzantine emperor … and an educated Persian on the subject of Christianity and Islam, and the truth of both.” This particular exchange, Benedict explained, “touches on the theme of the holy war,” and in it Emperor Manuel

addresses his interlocutor with a startling brusqueness, a brusqueness that we find unacceptable, on the central question about the relationship between religion and violence in general, saying: ‘Show me just what Mohammed brought that was new, and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached.’ The emperor, after having expressed himself so forcefully, goes on to explain in detail the reasons why spreading the faith through violence is something unreasonable.

The consequences of Benedict’s move, of his decision to include verbatim the evidence of Manuel II’s “startling brusqueness,” are now well known. The citation made news around the world and provoked fierce reactions. Upon hearing the Byzantine emperor’s words uttered by the Holy Father, many people decried the statement as the Pope’s unequivocal, general indictment of an inherent violence in Islamic thought and practice. Alongside discussions and debates across the globe about Benedict’s intentions, large and heated protests developed at various sites in Turkey, India, Pakistan, Gaza, and elsewhere. By the end of the same week, Benedict felt compelled to offer a public apology and explanation as part of his regular Sunday address: “I am deeply sorry for the reactions in some countries to a few passages of my address at the University of Regensburg, which were considered offensive to the sensibility of Muslims,” Benedict stated. “These in fact were a quotation from a medieval text, which do not in any way express my personal thought. I hope this serves to appease hearts and to clarify the true meaning of my address, which in its totality was and is an invitation to frank and sincere dialogue, with mutual respect” (as quoted in [

46]).

Indeed, a broad view of Benedict’s remarks reveal his emphasis on dialogue and partnership, as demonstrated in his concluding invocations of Manuel’s text and in other passages quoted above. Elsewhere in the speech—and even in the same paragraph, when he quotes sura 2:256 of the Qur’an (“There is no compulsion in religion.”)—the Pope tries to qualify and to temper the “startling brusqueness” of the Byzantine’s remarks. Nevertheless, the wider look at Benedict’s speech also makes clear his effort to delineate a clear and deep-seated distinction between Christianity and Islam in order to celebrate the “profound encounter between faith and reason” that occurred during the peculiar engagement of Christian theology with classical Greek thought. Building on a critical observation made by Théodore Khoury, the respected editor of and commentator on Twenty-Six Dialogues with a Persian, Benedict underscores Manuel II’s key point—“not to act in accordance with reason is contrary to God’s nature”—by calling attention to the Byzantine emperor’s opinions about how and why Islam strayed from this foundational Christian concept. “For Muslim teaching, God is absolutely transcendent,” Benedict summarized. “His will is not bound up with any of our categories, even that of rationality.” This perspective theologically justifies even seemingly irrational actions as consistent with divine will. While Benedict does not impute these characteristics onto all Muslims, a particular implication still haunts his discussion: Christianity and Islam occupy distinct theological territories, and the former more naturally reconciles reason with faith.

6. Throwing Fuel on the Rhetorical Fire: José María Aznar on “Living in a Time of War”

Pope Benedict’s September 12th speech set the stage for the events that developed in Spain over the following month. As in most places, a flood of opinions—from many social, religious, and cultural sectors and across the political spectrum—moved through the peninsula in waves in the days and weeks that followed. Notably, the debates carried out publicly in the media, in the halls of government, among religious communities, and elsewhere quickly shifted from the question of the Pope’s intentions—or used that issue as springboard—toward the issue of Islam’s essential nature and its implications in the contemporary world. In Spain, as in most places, the discussions centered on the inclusion of those contentious words about the “evil and inhuman” consequences of Muhammad’s staggering legacy despite the Vatican’s continued insistence that the words were the relic of a medieval text rather than the true sentiments of the pontiff. The focus on that single line suggests that most commentators probably did not bother to read Benedict’s fuller statement. And, even if they did, many probably remained confused or underwhelmed by his comparative reflections on the intricacies of Christian and Islamic theological development.

Still, the general disregard for the context of the Pope’s citation and the pervasive preoccupation with its ostensible indictment of Islam reveals a curious convergence of perspectives. Lending further credence to Samuel Huntington’s prediction that the metanarrative of a “clash of civilizations” would predominate public discourse in the early twenty-first century, the discussion in Spain of the Pope’s speech unfolded around the same assumption that structured the lecture itself, namely, that “Islam” and “the West” represented two fundamentally distinct and conflicting ideological entities vying for global influence and power. That symmetry of viewpoints serves as a vivid reminder that, while unique interests and apprehensions in Spanish society would refract public discussion of the Pope’s speech in certain directions, the conversations formed part of a spectrum of common concerns in Europe and elsewhere about the nature of Islam and its role in the contemporary world.

Those questions, as they related to Spain and its specific role on the geopolitical stage, surfaced explicitly ten days after the Pope delivered his talk in Regensburg and five days after his public apology for any offense the speech had caused. José Maria Aznar, one of the towering figures in the Popular Party as Spain’s former longstanding Prime Minister (1996 to 2004), raised the issues—and added a new dimension to the ongoing debates—while offering some brief remarks at the opening reception of a conference on “Global Threats, Atlantic Structures” sponsored by the Washington, D.C.-based policy think tank, The Hudson Institute

12.

In that context, Aznar took about fifteen minutes to provide some general reflections on the conference’s broad theme. He emphasized the need for the U.S., Spain, and other long-standing allies to recommit, even after the end of the Cold War, to “the Atlantic alliance” formalized after World War II in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) as a means to confront Soviet power. NATO remained essential, Aznar asserted. While it was still needed to contain post-Soviet Russian influence, the Atlantic states now faced another, even more nefarious threat: “radical Islam.” Aznar delineated the current state of global affairs as a matter of stark contrasts. He identified “the West” as civilizations stemming from western European culture and, therefore, rooted in Christianity. (“It’s impossible to explain Europe without Christian roots,” he insisted again and again [

47].) Because the Atlantic connected most of this “civilization,” a strong transoceanic alliance was indispensible to the survival of “the West.” In his view, survival remained the immediate reality in the face of the ascendant rival civilization he figured as “Islam.” “We are living in a time of war,” Aznar explained. “It’s them or us. The West did not attack Islam; it was they who attacked us.” He continued: “We must face up to an Islam that is ambitious, that is radical and that influences the Muslim world, a fundamentalist Islam that we must confront because we don’t have any choice. We are constantly under attack and we must defend ourselves.” In framing these comments, Aznar not only vigorously defended the Pope’s efforts at Regensburg to consider the theological roots of this “ambitious” Islam but also tried to redirect the outcry back at Benedict’s critics. The Westerners who take issue with the Pope are “soft,” Aznar contested, and take their cue from some of their own “leaders who don’t believe in the West.” Accordingly, the most “decisive task” we now face is a “battle of values” to preserve and to promote “Western civilization” [

47].

Despite their “startling brusqueness”—to borrow Benedict’s description in the Regensburg talk of the words of another, much earlier critic of Islam—Aznar’s comments came as little surprise. Both during and after his tenure as Prime Minister, Aznar had been one of President Bush’s most vocal supporters in the so-called “War on Terror.” Despite the opposition of a majority of his compatriots, he had committed Spanish troops and material support to efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq. Moreover, many observers attributed Aznar’s political undoing to an Al-Queda-linked terrorist cell that, through a series of coordinated explosions on March 11, 2004 along one of Madrid’s commuter train lines, killed 191 people and wounded around 1800 more. The attacks occurred three days before the general elections that voted Aznar’s party out of office amid a swirl of questions and suspicions about his government’s handling of the situation.

Still, in the midst of the debates already taking place about the Pope’s Regensburg speech, Aznar was bound to draw attention for his austere view of Islam and its “war” on “the West.” Even so, his biting comments did not end with his prepared remarks. Upon finishing them, he took a number of questions from his audience. One woman asked him to speak more specifically about “Spain’s views of Islam” today in light of its long historical presence in and deep influence on the Iberian Peninsula, beginning with the successful military campaigns of North African “Moors” in the early 700s until Ferdinand and Isabella’s takeover of Granada in 1492. Aznar acknowledged that history, but added: “It is interesting to note that, while a lot of people in the world are asking the Pope to apologize for his speech, I have never heard a Muslim say sorry for having conquered Spain and occupying it for eight centuries” [

47]. He concluded by invoking the expulsion edict by “the Catholic Monarchs” five centuries earlier, implying a need for a renewed effort—both in and beyond Spain—against the ambitions of the “radical” Islam that, to him, presented a real and severe threat. “I support Ferdinand and Isabella!” Aznar proclaimed. “They were a great king and queen” [

47].

Aznar’s unwavering endorsement of Ferdinand and Isabella—in a speech on global security, no less—pulls the Festivals of Moors and Christians back into view. After all, the festivals dramatize and commemorate precisely that history of Moorish “conquest” and Christian “reconquest” invoked by Aznar. And, just as a whole slew of questions circle around the implications of the festivals and their grandiloquent representations of Spain’s medieval past, a flood of responses and interpretations followed Aznar’s declaration that present threats to global security connected directly with Iberia’s historical “clash of cultures.”

13. Aznar’s comments quickly intensified the public discussion already underway about the Pope’s Regensburg speech and its implications. However, Aznar’s remarks also introduced a host of new questions and considerations into the discussions sparked by Benedict. Was there merit to his clear association between the complex, centuries-long cultural and political conflicts of medieval Iberia and the current state of world affairs, more than half a millennium later? Was the world population in 2006 really “living in a time of war,” much less one between “Islam” and “the West” that essentially stretched back to Islam’s origins in the seventh century?

Yet, despite the efforts of various commentators to isolate Aznar’s views as idiosyncratic

14, the uproar they caused reveals the wider socio-political stage on which the Moors and Christians festivals—and the debates about them—took place. The context becomes even clearer in additional comments that Aznar made in the concluding portion of his Hudson Institute talk. In the final question of the night, a member of the audience pressed Aznar for his views about the Alliance of Civilizations. He referred to the initiative brought in September 2004 to the United Nations General Assembly by José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, who—as head of the Spanish Socialist Party and one of Aznar’s longtime critics and political rivals—succeeded him as prime minister in 2004. In the aftermath of the bombings of the trains in Madrid that year, Zapatero called for the U.N. to take the lead in fostering international cooperation in overcoming problematic divisions between cultures, particularly the deadly opposition between “Islamic and Western civilizations.”

15. Turkey’s prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, co-sponsored the initiative, and on 14 July, 2005 the U.N. Secretary General announced the formal launch of “an Alliance of Civilizations aimed at bridging divides between societies exploited by extremists” and outlined the expectation of actionable recommendations by the end of 2006 that U.N. member states could adopt

16. Since the High-Level Group charged by the U.N. with developing those recommendations stood on the verge of releasing its final report at the time of the Hudson Institute conference, the questioner reminded Aznar, “Your party in Spain has been very critical about this idea launched by the current prime minister. But then President Bush and Secretary Rice have endorsed this idea of the Alliance of Civilizations as a way of engaging Islam in a dialogue—at least moderate Islam—so what’s your take on this project?” Once again, Aznar pulled no punches in his reply. “For me, the Alliance of Civilizations is stupidity,” he quickly retorted. “I’m in favor a dialogue between civilizations. […] But what does it mean, the ‘alliance of civilizations’? That we in the European Union, or the United States, should be in alliance, for example, with the Ayatollah’s regime? This is another ‘civilization’?” [

47].

At first glance, Aznar’s immediate dismissal of the Alliance of Civilizations initiative set in motion by Zapatero as sheer “stupidity” reveals the former prime minister’s deep political and ideological antipathies toward his successor

17. He underscores his opposition to the idea of excessive collaboration and insists that it is endemic to Zapatero and some of the other world leaders who, in preceding portions of his talk, he explicitly identifies as “soft.” In assessing diplomatic strategies, he explains that “alliances” should be reserved for allies, for those who share your “way of life,” so that you can “dialogue” with your adversaries from a position of cultural unity and political strength. Nevertheless, the audience member’s question about Aznar’s “take” on the Alliance of Civilizations already points to the significant common ground between Spain’s political rivals. Zapatero’s proposal of an “alliance of civilizations” serves as a clear signal that, although his tactics may have diverged substantially from Aznar’s views, both men accepted the kind of “civilizational approach” to global politics outlined by Samuel Huntington. Each operated with the notion that the dynamics among fundamentally different cultural blocks—and especially the opposition between radically opposed coalitions of “Islam” and “the West”—defined contemporary affairs. Accordingly, both men—or, more precisely, the major political parties they represented—sought to pursue their different “civilizational” strategies through domestic as well as international political mechanisms. When Aznar delivered his talk at the Hudson Institute conference in Washington, DC in late September 2006—two weeks after Pope Benedict’s Regensburg speech and two weeks before a slate of activities scheduled around Columbus Day and Hispanic Heritage celebrations in New York—discussions about U.N. proposals already reverberated across the Iberian Peninsula as part of a much wider set of debates about politics, religion, immigration, and culture and about the role of each of those elements in shaping who Spaniards “really” were and wanted to be.

7. Back to the Battlegrounds: Moors and Christians on the Rhetorical Front

Against the critical backdrop of the developments of the preceding weeks, we can return to where we started—October of 2006—and see more clearly how the Moors and Christians festivals surfaced at that moment as a flashpoint in Spanish public discourse. With continued coverage in the press about Aznar’s comments and the reactions they provoked, the

fiestas moved directly into the political spotlight. On October 4, Félix Herrero—the president of the Spanish Federation of Islamic Religious Entities and imam of the Union Mosque of Málaga—made the key move, narrowing the broad discussion of the role of Islam in Iberian history and culture toward more focused consideration of popular representations in Spain of Muslims. In light of Pope Benedict’s and Aznar’s speeches, Herrero offered the Moors and Christians festivals as an obvious and significant example. He issued a public statement in which he challenged the validity of the

fiestas and their portrayal of Muslims of the past, insisting that they negatively impacted Muslims of the present. Herrero called for the immediate suspension of the festivals. They “have no place in the democractic Spain of today,” he asserted. “In the service of the goal of peaceful coexistence [

buena convivencia] these festivals should disappear” ([

55]; see also [

56]). He objected especially to a component of certain celebrations in Alicante province, like those of Bocairent and Beneixama. In those towns, the

fiestas included a tradition in which the victorious Christians, after their final triumph over the Moors in the re-enactments, burned an effigy, called “El Mohama”—a clear reference to Muhammad—carried by the Moors’ front guard throughout the festival as a literal figurehead. In the course of the following days, festival organizers in both towns agreed to suspend the “Mohama” burning.

But, of course, the timing of the imam’s criticism of the festivals was not accidental. Building on the long-running efforts of UNDEF and of Spain’s diplomatic mission, La Asociación San Jordi [The Association of St. George], which oversees the town of Alcoy’s renowned Moors and Christians celebrations, had spent months preparing to send representatives to New York to march as Moorish and Christian “squadrons” in the upcoming Columbus Day and Hispanic Heritage parade. Imam Herrero was well aware of the mission’s intentions to apply for human-patrimony recognition. And there too his intervention proved effective. On October 6, the organizers from Alcoy, which hosts one of the oldest, largest, and most elaborate celebrations each year, decided at the last minute to break with their long-running and much-cherished tradition by changing their plans for the parade in New York. The group decided that the Christian regiments would march alone, without the squadrons of Moors (

Figure 7 [

57]). Javier Moreno, the president of La Asociación San Jordi, denied that pressure following Imam Herrero’s objections made any difference to the group’s representatives in New York. “It’s possible that the presence of the Moor [squadrons] could wound some sensibilities,” he acknowledged after announcing the decision, “but if they’re not here it is simply because that the Christian procession has more rhythm than the Moor one, and was better to head the parade” [

58]. He added: “In Alcoy there are no polemics. Other people create polemics with declarations that are respectable but gratuitous. All of the squadrons—Moor and Christian alike—represent the people.” With similar assurances that the decision was “exclusively a matter of infrastructure,” Amparo Ferrando—Alcoy’s Councilor of Tourism as well as one of the Popular Party’s national deputies—insisted, “our festivals portray historical events and are not a matter of, nor offensive to, any particular religion” [

58].

Despite these explanations, many supporters of the festivals took issue with the decision to abandon the Moors. The debate about the fiestas—beginning with Herrero’s initial statement on 4 October—had garnered widespread coverage in the national press throughout the week and, with the news of the Moorish squadrons’ absence from the New York exhibition, the Popular Party decided to act. The stage was set for Eduardo Zaplana’s announcement on Friday, the thirteenth, that the PP would bring the non-binding resolution to the lower legislative house to win support for the festivals’ “human patrimony” candidacy. As Zaplana asserted in explaining the unprecedented move, the Popular Party saw the need for a courageous counterattack in order to defend free expression in the face of the “debilitating self-censorship” recently on display with regard to the fiestas.

Figure 7.

‘No more Moors!’ A Christian squadron from Alcoy (province of Alicante) marches alone, without traditional Moorish counterparts, down Fifth Avenue in New York’s Hispanic Heritage and Columbus Day Parade, 9 October 2006.

Figure 7.

‘No more Moors!’ A Christian squadron from Alcoy (province of Alicante) marches alone, without traditional Moorish counterparts, down Fifth Avenue in New York’s Hispanic Heritage and Columbus Day Parade, 9 October 2006.

Photo by Miguel Rajmil/EFE [

57].

The Popular Party’s move complicated the ongoing public discussion of the festivals. Although the party took up the cause of promoting the Moors and Christians celebrations for UNESCO designation, local representatives of the festivals strongly criticized the initiative. UNDEF should coordinate the effort, they noted, not some political organization. As one member of the UNDEF commission put it, the process of applying for international recognition “should be separate from any opportunistic and electoral maneuver … to confuse our respected celebration with politics” [

59]. Accordingly, Zaplana’s announcement effectively shifted the national debate away from questions about Islam and representations of Muslims to the issues of politicization of local traditions. The driving concerns became a matter of who has the right to represent popular celebrations—the Moors and Christians festivals or otherwise—and how to do so. In this way, the

fiestas remained in the press and part of the national conversation for the next month and a half

18. Finally, on 21 November, UNDEF filed a formal petition with the Spanish government to direct the process of filing for UNESCO recognition, undercutting the Popular Party’s efforts to take control of the issue. Even though political skirmishes—and public interest in them—continued through February, when the Popular Party eventually presented the

fiestas to the national legislature for UNESCO candidacy, the measure never came before the full Congress of Deputies for approval

19. Public debate about the festivals largely died down. With or without UNESCO’s official stamp, townspeople and tourists continued with their preparations for and participation in the celebrations

20.

8. Final Battles: The Fiestas Un-Moored

Although the political showdowns over the Moors and Christians festivals finished with more whimper than bang—and also proved, after all, fairly short-lived—the episode demands a bit more consideration. In the concluding portion of this essay, I want to return briefly to one of the climactic moments in the series of developments that played out in the wake of Pope Benedict’s Regensburg speech. As noted earlier, the announcement on October 6 that the Alcoy representatives in New York would march without squadrons of Moors marked a critical moment in the public debates that had developed in Spain about Islam and its place in the history and culture of the Iberian Peninsula. The decision not only sparked widespread discussion but also provoked the Popular Party’s legislative initiative.

Upon closer examination, the explanations offered by Javier Moreno and Amparo Ferrando—two of the officials responsible for the decision quoted earlier—are similarly provocative. Whether or not Moreno and Ferrando really believed what they said—namely, that political pressures did not play, or should not have played, a part in the decision to keep the Moor squadrons out of the New York parade—a sense of understandable uncertainty and defensiveness inhabits their explanations. As primary spokespeople for Alcoy participants, both speakers acknowledged that their traditions were under public fire, shrouded by suspicions of prejudice. The inclusion of Moorish squadrons might “wound some sensibilities,” Moreno admitted, although Ferrando emphasized that the festivals are “not … offensive to any particular religion” despite what some observers might think. Yet, along with diffidence, a tone of melancholy resonates in their responses. And why not? They knew that something was missing. Their town’s famous traditions, as displayed publicly in New York, lacked something fundamental. After all, what are the Moors and Christians celebrations without the Moors? That simple and seemingly obvious question points us back to the actual structure and content of the fiestas. The move also forces us to turn the analytical lens around. Rather than examining the socio-political context to gain insight into the festivals, we can look to the festivals to illuminate the socio-political context.

That critical turn is productive since, as it happens, the showdown between “Moors” and “Christians” in the

fiestas is more complicated than it initially appears. As Daniela Flesler masterfully delineates in “Playing Guest and Host”—a key chapter on the festivals in her 2008 volume,

The Return of the Moor—“an essential ambivalence” inhabits the celebrations and, in turn, that tension both expresses and produces a deep sense of unease in the

fiestas and in Spanish society more broadly [

24]

21. In a short piece for readers of

The Guardian (UK), British travel writer Andromeda Agnew picks up on a strange pattern, one that Flesler subsequently explores in greater depth. In observing a variety of Moors and Christians celebrations in Alicante province, Agnew casually notes how “the festivals give [Spaniards] a chance to revel in their Islamic ancestry.” The celebrations trumpet the cultural sophistication of the Moors of Spain’s past. “In contrast to the magnificent yet cumbersome armour of the Christians, the Moors float down the street, resplendent in yellow and purple chiffon. These characteristics confound her initial expectations. “Everyone wants to be a Moor!” she observes [

17].

In “Playing Guest and Host,” Flesler pursues this idea even further. She too underscores the point that the role-playing on which the festivals depend arises from the desire to celebrate Spain’s Moorish legacy and, more immediately, to claim it as a unique and foundational component of Spanish culture and identity. However, Flesler follows her deconstructionist intuitions—already figured in the title of the essay—and argues that such assertions of identity belie uncertainties about who “belongs” in Spain and, in turn, to whom the land “belongs.” Who is “guest,” and who is “host”? Drawing on Jacques Derrida’s and Sarah Ahmed’s considerations of those categories to illuminate the roles acted out in the festivals, Flesler shows how “the efforts to delimit clear spaces of separation fail. Moors and Christians become simultaneously guests and hosts in what Homi Bhabha calls a ‘third space’ that is neither one of complete separation nor one of homogenization” ([

24], p. 97).

In this way, Flesler looks beyond immediate appearances. As already noted in my initial description of the festivals, everything about them conveys the sense of encounter between distinct cultures. Again, to describe the celebrations in Huntington’s terms, they dramatize the spectacular “clash of civilizations.” As Flesler summarizes, “the true protagonist of these celebrations is the excess that permeates all the festive rituals at both the discursive and performative levels” ([

24], p. 101). For, through “the rhetorical excess,” the festivals present “narratives that aim at justifying an essential, Christian right to the land, while explaining away the presence of the Moors as something temporary and inconsequential” ([

24], p. 102). From this angle, the spectacular dramatizations of local legend really speak to contemporary circumstances. Flesler explains: “The preoccupation with current changes in the racial and ethnic composition of Spanish society is displaced into a distant and safer past.” Thus, “the festivals are plagued by an anxiety of delimiting, in that past, the concrete space occupied by each group, to ensure that the limits appear well-established” ([

24], p. 97). The context of the festivals makes the “anxiety of delimiting” particularly acute. As noted earlier, not only was the Islamic legacy long and rich in the area of Valencia Community that serves as the heartland of the celebrations but the region also remains one of the main destinations in Spain for Muslim immigrants as well as tourists.

Furthermore, by locating the apprehension at the heart of the process of “delimiting” that the festivals attempt to enact, Flesler stresses how the efforts to establish those limits ultimately fail. The boundaries of distinction, so clearly marked in every aspect of the performance, constantly break down as the roles of Moors and Christians continually flip back and forth. As Flesler summarizes,

within the many rituals of separation between the two sides that make up the festivals, there are traces that reveal how the official discourse making the Christians as hosts is only intelligible if one notes their position as guests in that same territory. During the celebrations, each one of the groups takes turns at occupying the position of host, [serving alternately as victors and victims, possessing and losing the castle,] with an awareness of the transitory nature of this role, aware that both in the festival and in the history of the area, both Moors and Christians are guests.

Despite the spectacular mechanisms employed in the festivals to delimit roles and to distinguish “Moors” from “Christians,” the collapse of those boundaries occurs not only in fleeting moments but also in obvious ways at critical junctures of the proceedings. For instance, the climax of every Moors and Christians fiesta—regardless of its length and complexity—arrives with the Christians’ “reconquest,” after a prolonged battle, of the territory overtaken by the Moorish invaders during the early stages of the festival. At that critical moment, the Moors leave and the Christians enter the castle (or other symbolic stronghold) on which the preceding battles focused with all of their booming retorts from life-size guns and canons. In this transposition of conqueror and conquered, the troops come into direct contact. Their leaders address each other in extended dialogue. The confrontation represents the dramatic apex of the entire festival, as the Moorish leader expresses despair at the loss and pleads for compassion. The Christians weigh the request—usually with a conflicted and laborious consideration of the facts—before finally expelling the Moors from the land.

The conclusion of the 2012 celebration in the San Blas neighborhood of Alicante offers an outstanding example

22. As the Moor and Christian groups faced each other across the final “battleground”—in fact, a local intersection where organizers erected the stage-set castle—the Moors’ emir emerged from among his battalions. In a long monologue presented in the rhetorical style of a medieval epic poem and directed toward the Christian leaders—the queen and her generals—standing at the head of their army, the emir acknowledged his peoples’ defeat and the loss of their possessions (

Figure 8). He felt “pitiful” and lamented his “broken soul” [

alma partida] now that the Christians were forcing him and his community to leave. “Blood ties me to this land,

my land!” he cried. His own blood as well as that of his family and of his people had mixed with that soil, where generations of his ancestors were buried [

enterrados]. Banishment, “

el destierro”—literally, “removal from the land”—felt worse than death to them, he wailed. As “exiles,” the Moors would be completely …

unmoored! In turn, the emir’s emotional petition moved the Christians. Holding his head in his hands, their lead general agonizes over what to do. “I feel two impulses,” he cried. “I don’t know … to punish or to pardon?!” [

Siento los dos impulsos. ¡No sé! ¿Condenar o perdonar?] And then, quickly finding his resolve and acting on it before it leaves him, he issued his final command: “Leave now! Take your liberty instead of death!” As the Moors marched solemnly past him and the other Christians, unmoored after all, the general recovered his conviction. “Alicante is now Christian! Glory to God!” he proclaimed. In light of the obviously conflicted emotions of the preceding action, an uncertainty echoed from the general’s words. His pronouncement sounded more like a statement of possibility than of fact. Either way, he led his charges into the reclaimed castle to the rhythm of the victory march rising from the loudspeakers temporarily installed in the streets.

Figure 8.

After the “reconquest,” the Moor emir pleads for mercy from the Christian queen. San Blas neighborhood, Alicante city, 9 July 2012.

Figure 8.

After the “reconquest,” the Moor emir pleads for mercy from the Christian queen. San Blas neighborhood, Alicante city, 9 July 2012.

Photo by author.

While the words and details may differ from festival to festival and place to place, San Blas’s 2012 iteration portrays a now-familiar scene. In almost every case, the final encounter follows the same general script: the lamentations of the Moor leader of the impending destierro, of the final unmooring from the beloved place; the conflicted emotions of the Christian figureheads; uncertainty followed by the sudden, resolute expulsion of the defeated…. Watching these dramas, with their flip-flopping roles and obvious ambivalences—highlighted through the performers’ histrionics and only made more apparent by the Christian leaders’ artificial claims to definitive victories—the questions raised by Flesler rush to the surface: Who is ‘guest’ here, and who is ‘host’? Who “belongs” to these lands, and to whom do these lands “belong”? In the end, the “clash of civilizations” portrayed in such exaggerated terms in the festivals—the narrative of Muslim ‘invaders’ versus Christian ‘natives’—feels more like a showdown of intimate adversaries, if not a nasty family quarrel.

In this way, the different rhetorics of the festivals—their overarching clarity countered by the palpable uncertainties—conflict. When all is said and done, the overriding carnivalesque quality of the

fiestas points to the fact that the celebrations truly are carnivals, in the vein of Spain’s long and abundant tradition of popular rituals: The Moors and Christians festivals provide a release from the strictures of everyday expectations, as Bernabeu Rico argues ([

19], p. 99); they unsettle social roles and hierarchies, as Harris explains ([

25], pp. 48, 59). And, as noted earlier, the stylized battles on the streets create “semiotic battlefields” where conflicting meanings and interpretations of audience and actors alike take shape and play out. Still, the festivals speak clearly of a popular desire to present Spain as an exemplar of “

convivencia”—cultural and religious coexistence—by embracing the legacy of the Moors (and Jews and others). Yet, in order to sustain this claim—a “multiculturalism

avant la lettre,” as Flesler calls it ([

24], p. 97)—those ‘other’ elements must be constrained within the controlled spaces of the medieval past or the ritual present. But as this ideal of

convivencia circulates through the mock confrontations and resolutions of Moors and Christians, what other meanings and desires make their way onto the “semiotic battlefields” of the

fiestas? What do tourists take from the dramas? And, more pointedly, what do they say to “the Moors” of today, including the thousands of Muslims who reside—whether as recent immigrants, long-time residents, or new converts—in the places where the celebrations occur?

23.

A viable catalog of answers to those questions, much less feasible analysis of responses, falls beyond the scope of the present essay. Nevertheless, the queries pull our attention back to the primary topic at hand. The image of the Alcoy contingents in New York’s Columbus Day parade comes back into view, and it is striking (see

Figure 7). As the Christian squadrons march alone down Fifth Avenue, without their familiar counterparts and out of their usual context, they appear a bit like those adversaries at the conclusion of the typical

fiesta back home. They appear, literally and figuratively, unmoored. As a representation of “Spanish culture”—much less of the festivals themselves—the picture is incomplete, and the glaring absence of Moors among the Alcoy procession paradoxically heightens our awareness of the overarching reality of Iberian history as well as its continual re-imaginings in cultural forms like the

fiestas: The Islamic presence, whether as an enduring power from the past or as a collection of immigrants and converts in the present, remains indispensible to the idea of “Spain” as well as to social realities on the peninsula across many centuries.