2. The Cosmic Creation Imagery in True Explanation of the “Changes”

The relationship between alchemical practices and the

Book of Changes has a long history, exemplified by the

Book of Changes cantongqi (周易參同契), known as “The King of All Ancient Alchemical Texts,” (萬古丹經王), which utilizes the ideas of the

Book of Changes to elaborate on Daoist alchemical thought. Liu Yiming recognized the

Book of Changes’s role in elucidating alchemical practices early on; before the third year of the Jiaqing era (1798), he had finished writing this book, his earliest work, demonstrating his emphasis on studying the

Book of Changes. Among his methods of annotating the

Book of Changes, illustrating the text was one of his most important approaches. He believed:

the way of the Book of Changes is vast and boundless; there is no external boundary and no internal limit. Its principles are subtle and hidden, and its meanings are profound. Each Figure has its own significance... One who does not understand the principles of the hexagram’s formation and division cannot read it.

The way of the Book of Changes encompasses all things, and its meanings are often expressed through images, which also change in accordance with the transformations of the hexagrams. Moreover, according to some traditions, such as He tu, understanding the way of the Book of Changes cannot be separated from a precise grasp of the changes shown in the Figures of the Book of Changes.

Under the guidance of the idea that “the way of alchemy is the way of the

Book of Changes,” Liu Yiming took the cosmological theory of the

Book of Changes as the metaphysical foundation for his

Neidan theory, using black-and-white dot Figures to explain the

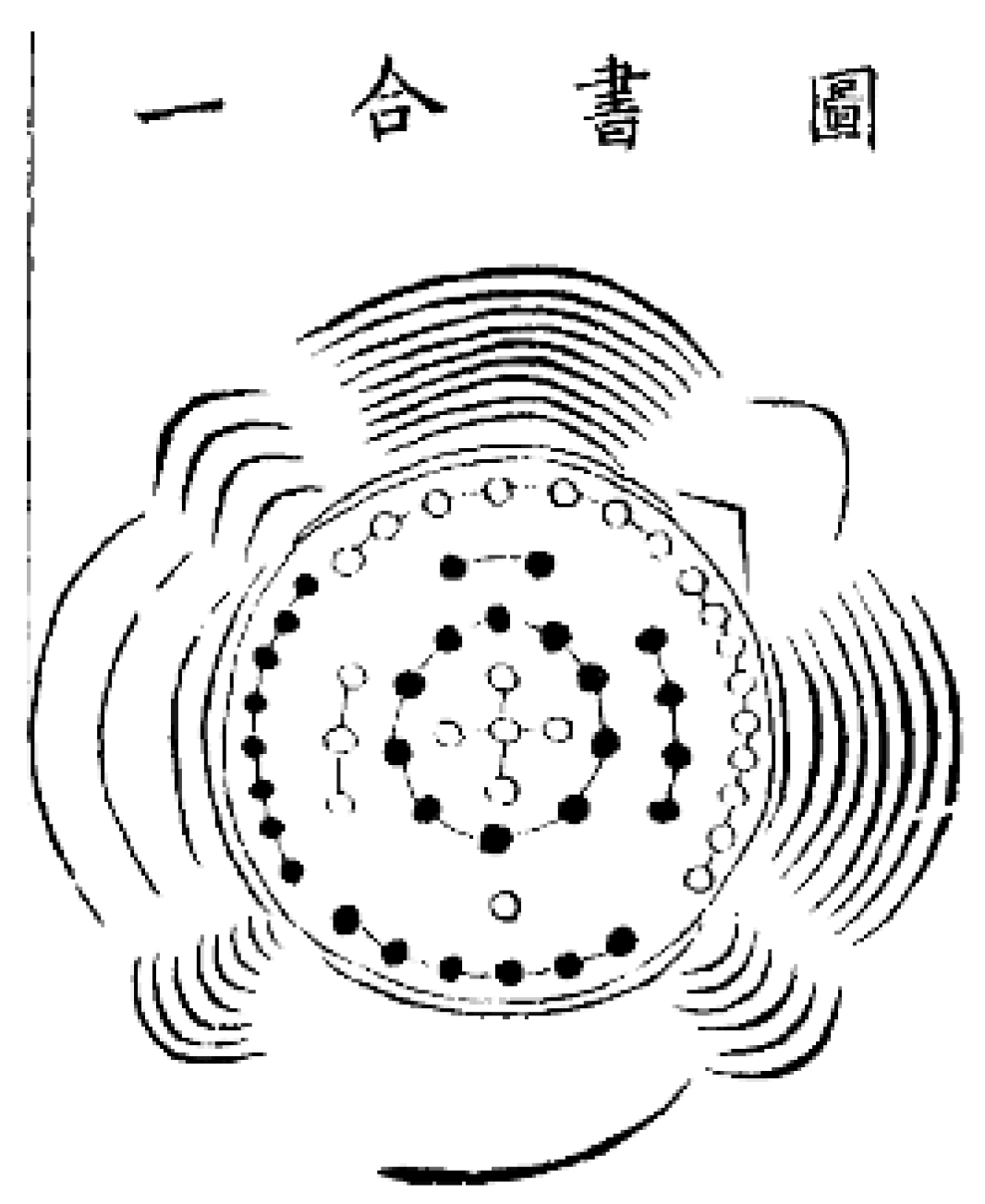

He tu and

Luo shu (洛書). In fact, “the black-and-white dot Figures of the

He tu and

Luo shu were an important innovation in Song dynasty

Book of Changes studies, and this style of Figure originated with Liu Mu (劉牧) of Pengcheng” (

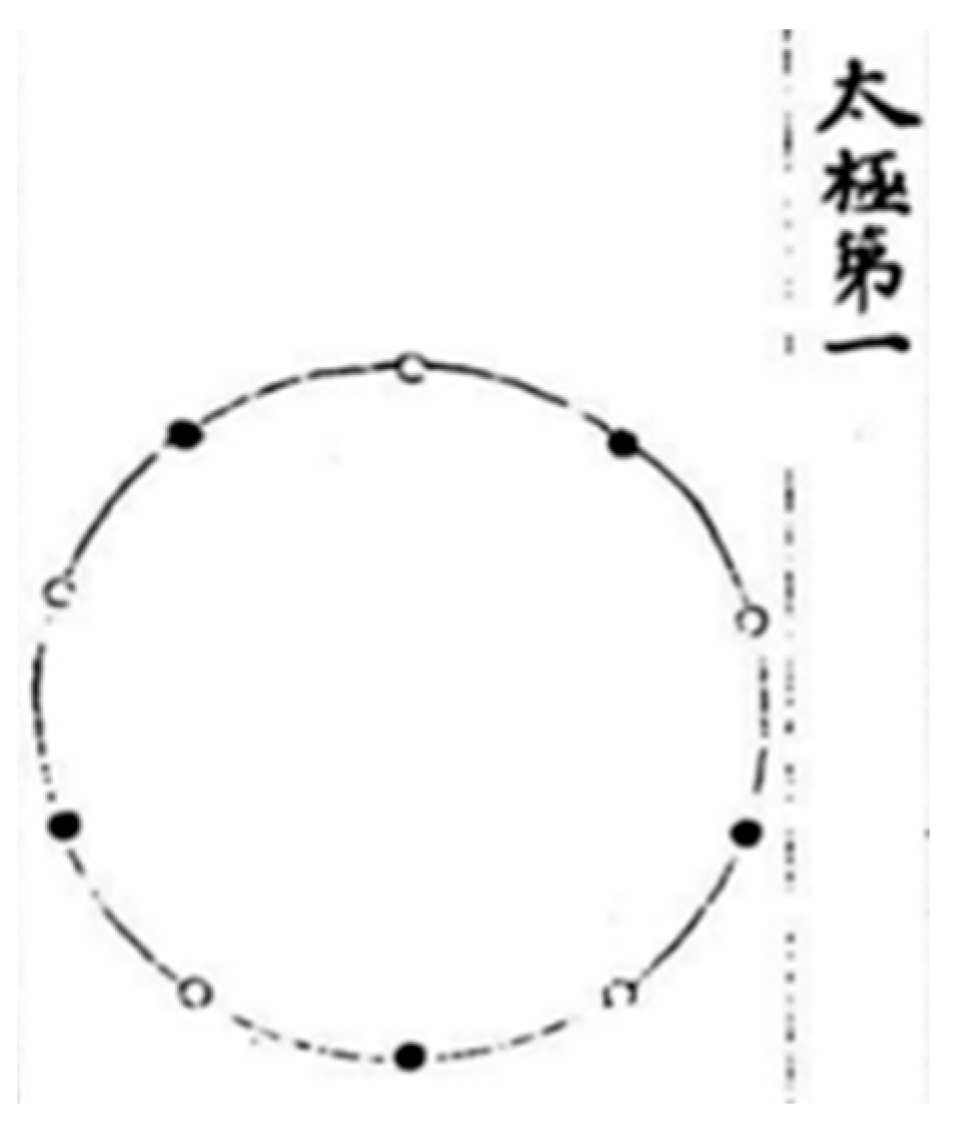

K. Zhang 2024, p. 5). In his work

Yishu Gouyin Tu (易數鉤隱圖), Liu Mu created a

Taiji tu 太極圖 (Figure of the Supreme Ultimate) (

Figure 1), where the Supreme Ultimate (太極) is represented as a circle formed by black and white dots.

Supreme Ultimate by itself has no number or image. Now, by blending the energies of the

yin and yang (陰陽) into one and drawing it, I intend to clarify the source from which the Two Modes are born” (

M. Liu 1988, vol. 3, p. 201). This means that the Supreme Ultimate originally had no numerical or symbolic expression. The black-and-white dot Figure of the Supreme Ultimate he created is an intuitive representation of both the number and the image of the Supreme Ultimate. In this system, white and black dots represent odd and even numbers, respectively, corresponding to the

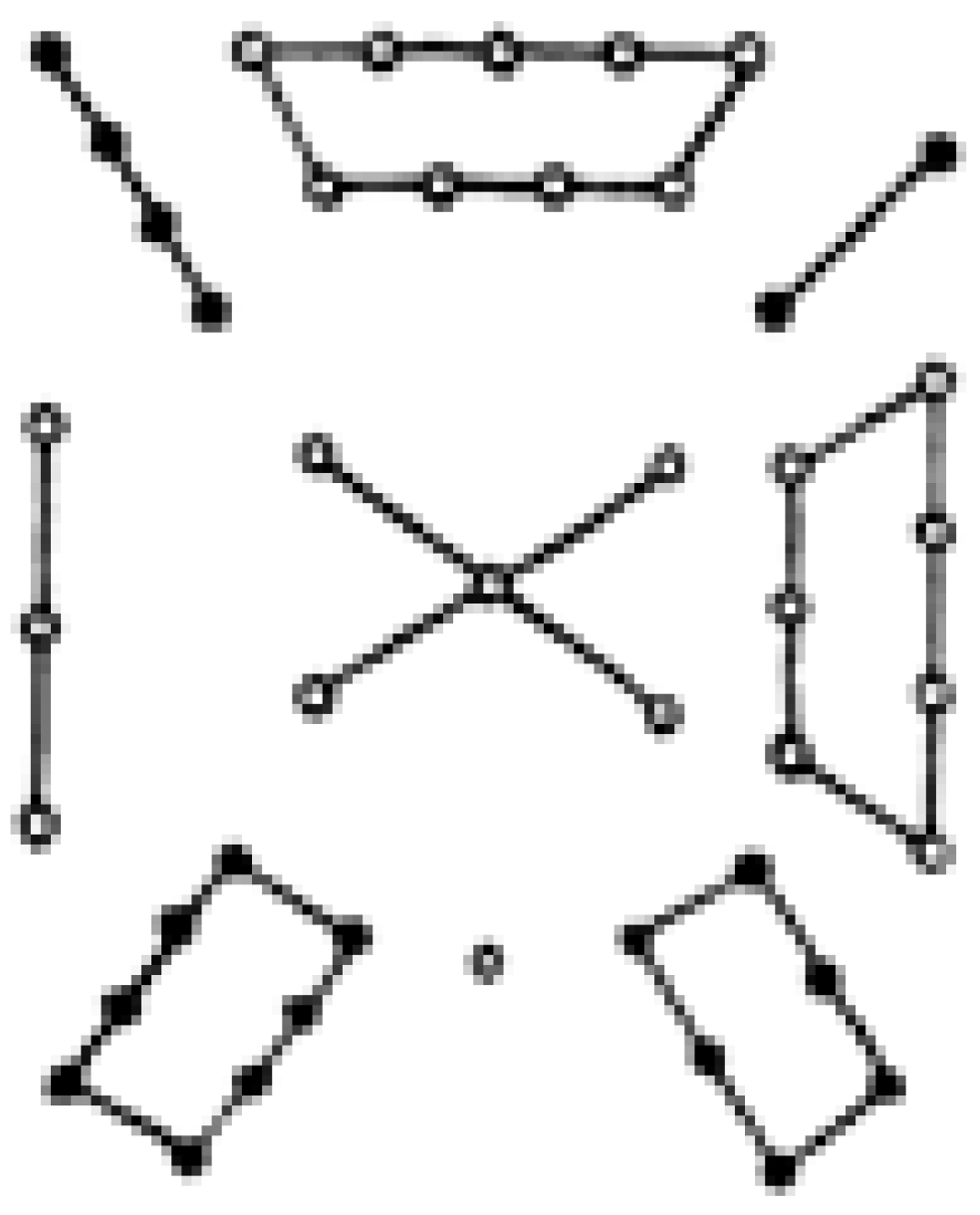

yin and yang of the Two Modes. More importantly, Liu Mu also applied the black-and-white dot method to the

He tu (

Figure 2) While theories about the

He tu have existed since ancient times, the earliest known Figure of the

He tu is Liu Mu’s black-and-white dot Figure. (黑白點式圖) He wrote:

In ancient times, when the sage-kings ruled the world, they observed the auspicious appearance of the dragon horse, which bore the numbers of Heaven and Earth as it emerged from the Yellow River. This is called the ‘dragon Figure.’ With nine above and one below, three on the left and seven on the right, two and four as the shoulders, six and eight as the feet, and five as the heart—whether counted vertically or horizontally, the sum is always fifteen.

This is the source of Liu Yiming’s own He tu Figure, upon which he further innovated. The use of black-and-white dot Figures makes the distinction between yin and yang more visually immediate and facilitates the interpretation of the alchemical ideas embedded within.

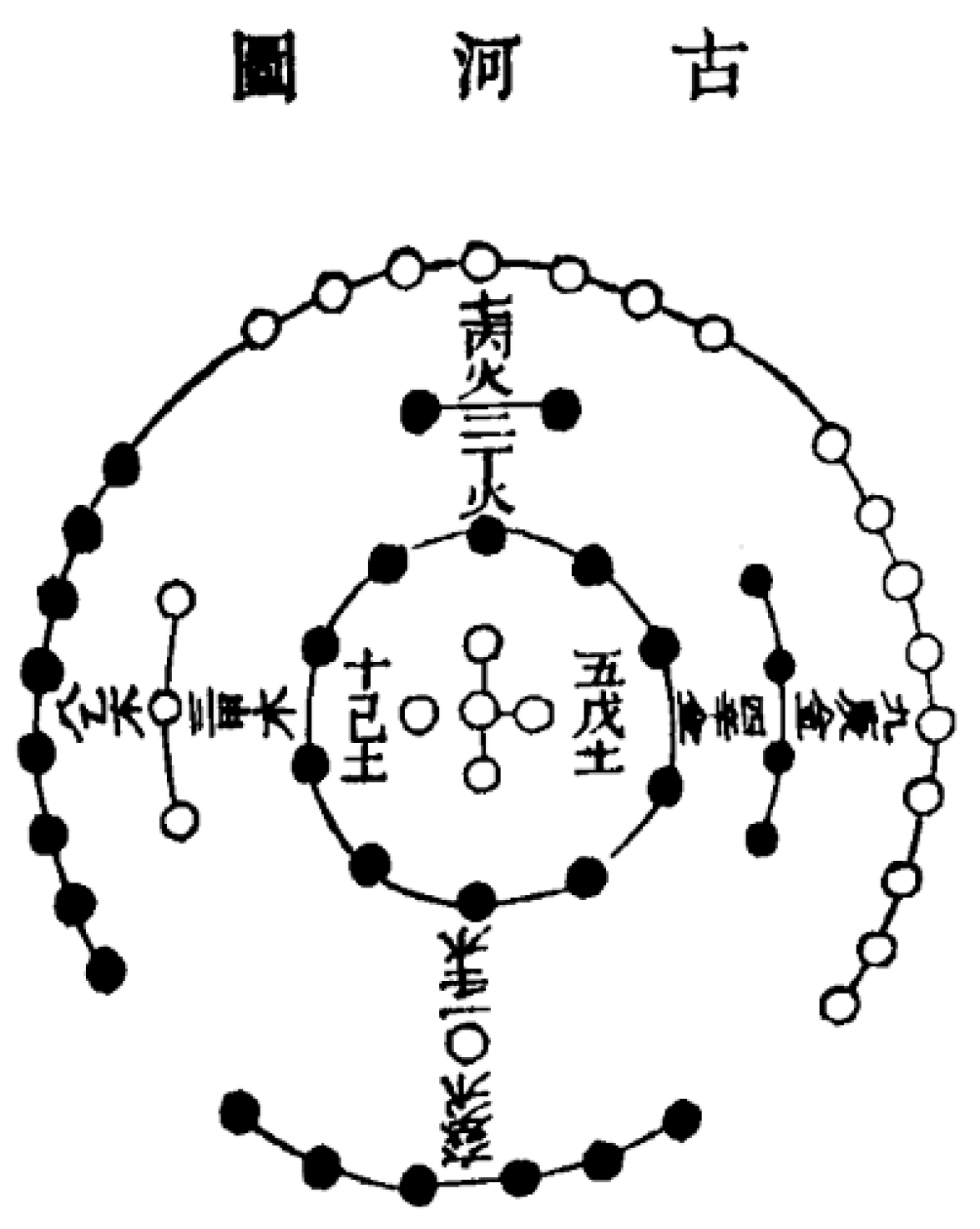

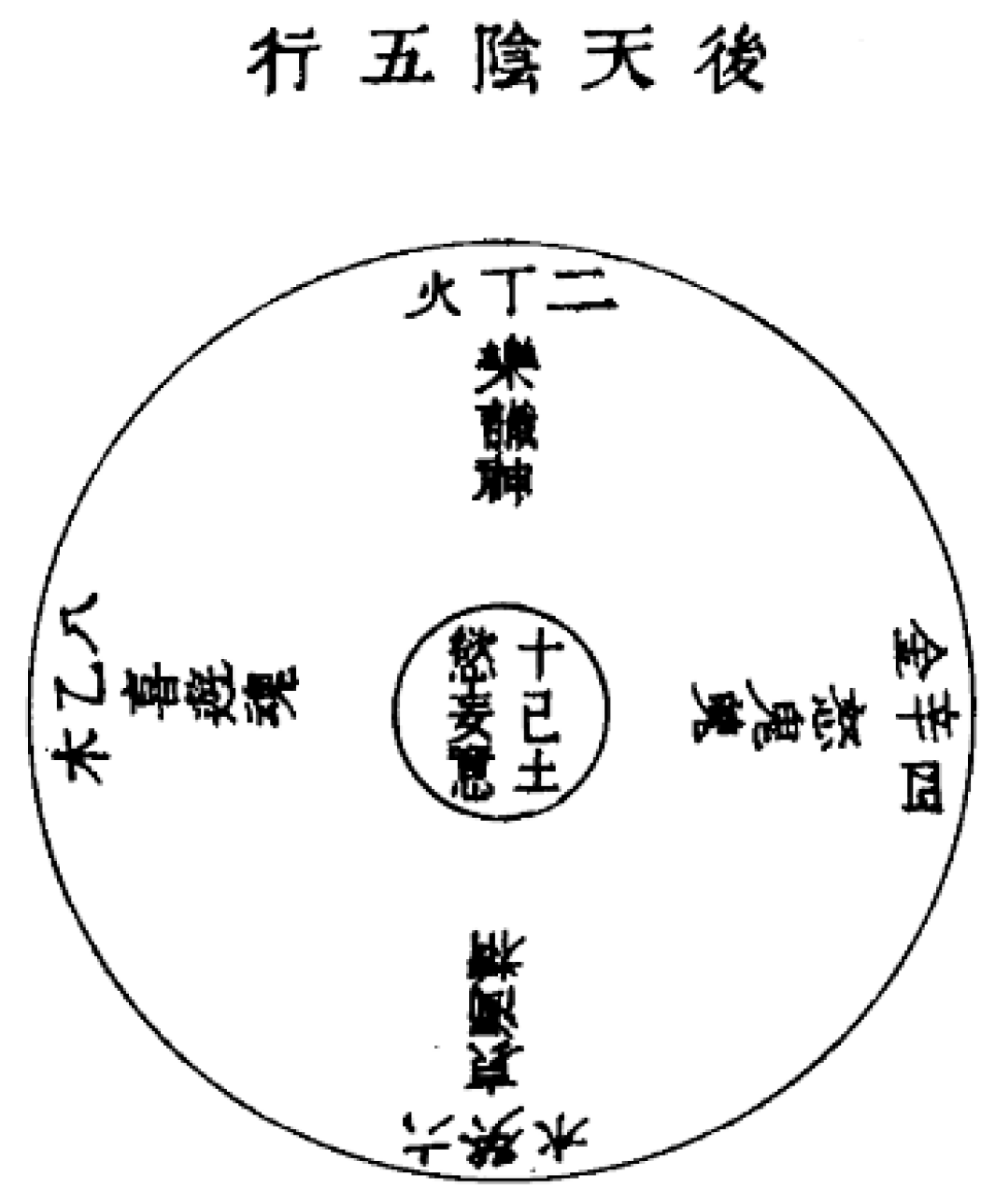

First, Liu Yiming summarized the core idea of the

He tu (

Figure 3), stating that, “The

He tu represents the sequential movement of the Five Elements (五行), which is the Way of Nature and Non-action (自然無為之道)” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 7). Furthermore, he provided a detailed explanation of the images depicted in the

He tu:

In the time of Fuxi, a dragon horse emerged from the Meng River, bearing dots on its back: two and seven in front, one and six at the back, three and eight on the left, four and nine on the right, and five and ten in the center. The positions and images correspond to the Five Elements: one and six at the back represent the northern ren (壬) and gui (癸) water; two and seven at the front represent the southern bing (丙) and ding (丁) fire; three and eight on the left represent the eastern jia (甲) and yi (乙) wood; four and nine on the right represent the western geng (庚) and xin (辛) metal; five and ten in the center represent the central wu (戊) and ji (己) earth. The five dots in the center also symbolize the Supreme Ultimate containing the Four Images; the single central dot also symbolizes the Supreme Ultimate containing the One qi (一氣). Although there are fifty-five dots in total, in fact, it is two groups of five; the two fives are actually one five; and the one five is ultimately the single one in the center. Because there are Five Elements, they are divided into five dots; because each of the Five Elements has yin and yang, they are combined into ten dots; and because each of the Five Elements contains both yin and yang, this results in a total of fifty-five dots.

Clearly, Liu Yiming believed that the images of the

He tu illustrate the order and arrangement of

yin and yang, and the Five Elements, and that the meaning behind these images reflects the process of cosmic generation: “The way of Heaven and Earth’s transformation (天地造化之道) is nothing more than one yang Five Elements and one yin Five Elements, one generation and one completion. Although the Five Elements are divided, in reality, it is the operation of one

yin and one

yang; although

yin and yang operate, in reality, it is the circulation of one

qi” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 7). Thus, in Liu Yiming’s view, both

yin-yang and the Five Elements originate from

qi, which is a typical Daoist cosmology of generation by

qi (氣).

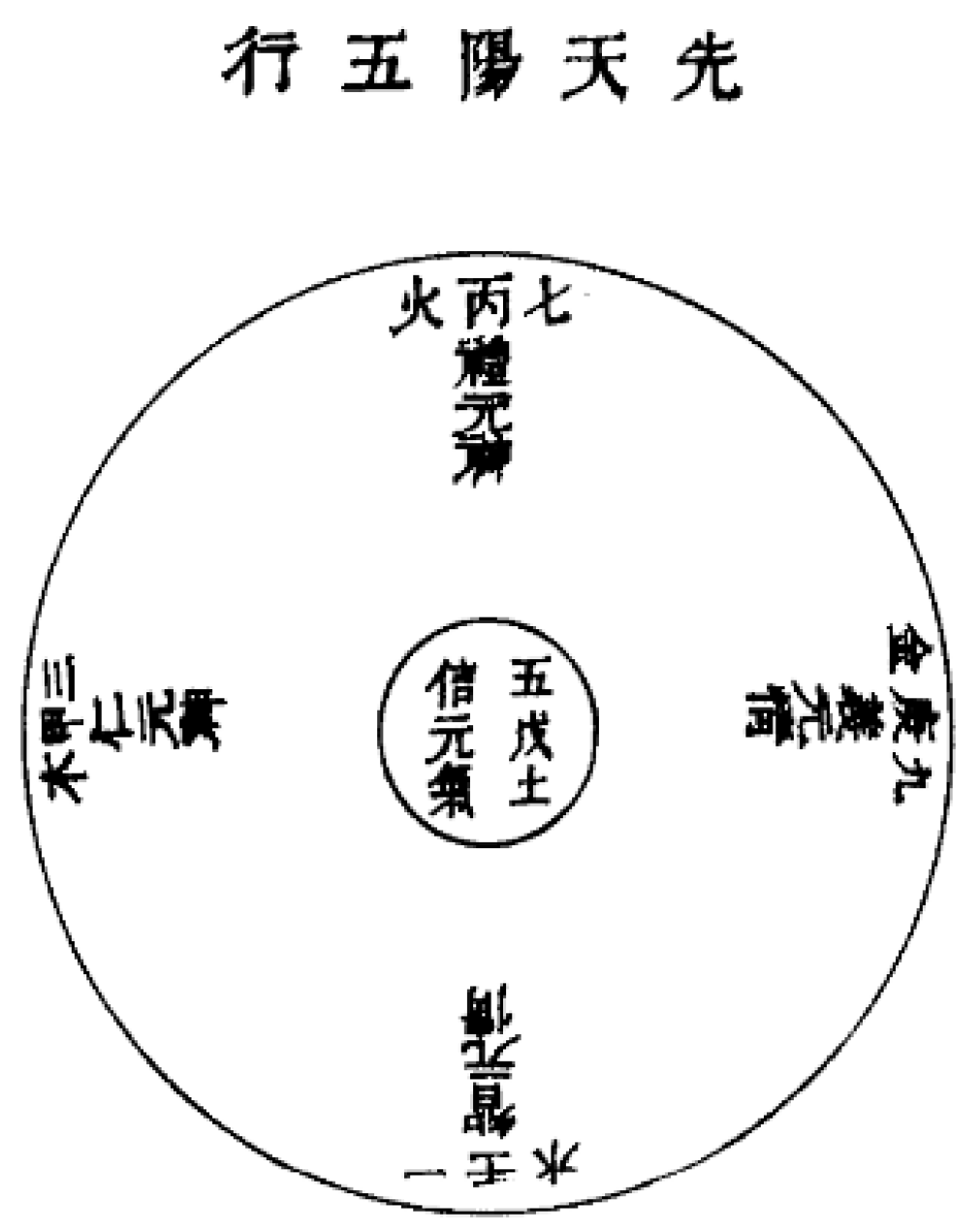

Liu Yiming’s main innovation regarding the

He tu was to divide it into two parts: the Pre-Heaven (

xian tian 先天) and Post-Heaven (

hou tian 後天)

He tu (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). He stated:

But these Five Elements have Pre-Heaven and Post-Heaven aspects; the Pre-Heaven Five Elements belong to yang, while the Post-Heaven Five Elements belong to yin. The numbers 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 represent the yang Five Elements, whereas 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 represent the yin Five Elements.

In this way, Liu Yiming distinguished the Five Elements in the

He tu into the Pre-Heaven and Post-Heaven parts according to

yin and yang. The Pre-Heaven Five Elements, consisting of 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 are, respectively, assigned to the five origins of essence (

jing 精), nature (

xing 性), energy (

qi 氣), spirit (

shen 神), and emotion (

qing 情) From these five origins are further produced the five virtues (

wu de 五德), and these Pre-Heaven five origins and virtues are present within the human fetus, forming the foundation for returning to the Pre-Heaven state through

Neidan practice. Similarly, the Post-Heaven Five Elements consist of 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 are, respectively, assigned to the five entities of discriminative consciousness (

shi shen 識神), ghostly soul (

gui po 歸魄), turbid essence (

zhuo jing 濁精), wandering soul (

you hun 遊魂), and deluded intention (

wang yi 妄意) These five entities in turn produce the five thieves, which arise after a person’s birth and are the reason why people cannot become immortals. In this way, “Liu Yiming not only used the

He tu as a tool for interpretation but also regarded it as the object of interpretation” (

Xiao 2020, p. 77).

Post-Heaven should be governed by Pre-Heaven, but after the age of sixteen, it is easy for people to completely fall into the Post-Heaven state and lose their

yang qi, which is why people die and cannot become immortals. In fact, “following leads to immortality, while opposing leads to human life” (順則生人, 逆則成仙) is a core Daoist alchemical principle. Liu Yiming’s innovation was mainly the use of

Book of Changes Figures to illustrate this principle. He stated:

In the He tu Five Elements, yin and yang are united, and qi is harmonized; this is the way of the sages’ reverse operation. Reverse operation does not mean going back, but rather, storing the Five Elements in reverse, returning them to the central yellow Supreme Ultimate, and thus regaining the original face before one’s parents were born.

In this way, the

He tu reveals the fundamental principle of the alchemical path. However, some scholars have pointed out that “Liu Yiming’s understanding of ‘the reversal in the

Book of Changes’ was also deeply influenced by Shao Yong 邵雍.” (

Shang 2021, p. 95) Regardless, he applied this principle to

Neidan and additionally, he incorporated the important Daoist alchemical concept of “

xing and ming” (性命) into the

He tu. Cultivating both “nature and destiny simultaneously” (性命雙修) is the basic method of alchemy, because “the late Tang and Five Dynasties was the period when

Neidan gradually matured, characterized by the principle of ‘cultivating both nature and destiny simultaneously’” (

Shen 2020, p. 22). In Daoism,

xing and

ming are as described in

The Guiding Principle of Life and Death (性命圭旨): “What is called nature? It is the original true suchness (

yuanshi zhenru元始真如), a singular, radiant spirit. What is called destiny? It is the most refined Pre-Heaven

qi, a unified and diffuse energy(

xiantian zhijing先天至精)” (

Wang 2022, p. 12). That is to say, in Daoism, both nature and destiny originate from Pre-Heaven; their distinction lies in their division between Heaven and humanity, but they are fundamentally one. This also reflects the traditional Daoist idea of the unity of Heaven and humanity in the practice of

Neidan.

Second, after interpreting the

He tu, Liu Yiming further elucidated the ideas of

Neidan contained within the

Luo shu. Regarding the

Luo shu, he stated, “The

Luo shu (洛書) is the intricate interweaving of

yin and yang, the reverse movement of the Five Elements, and the way of transformative action” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 11). He believed that the

Luo shu reflects the path of generation and control among the Five Elements (

Figure 6), and that within the process of mutual generation and control of the Five Elements, the principles of human life and the method for returning to the Pre-Heaven state are already implicit. Returning to the Pre-Heaven state means returning to the fundamental root of nature and destiny, which is what Laozi called “the gate of the mysterious female, which is the root of Heaven and Earth” (

Wang and Lou 2008, p. 16). This is also known as the especially crucial “mysterious pass—the single aperture” (玄關一竅) in

Neidan practice. Liu Yiming gives a more detailed explanation of this in his

Refuting Difficulties in Cultivation (修真辨難), saying:

The Original Pass (Yuan guan 元關) has no form or image, how could it have a fixed location? It is neither colored nor empty, so how could it have a particular place? If we were to assign it a location by form, it would become a thing with form and image, and could no longer be called the Original Pass.

It is not difficult to see that Liu Yiming’s

Neidan thought is imbued with the spirit of the integration of the Three Teachings (三教融合) This is because the founding of the Quanzhen tradition itself was based on the integration of the Three Teachings. Liu Yiming greatly approved of this, as he wrote in the preface to

The True Meaning of Journey to the West (西游原旨序): “Journey to the West (西遊記) was written by Changchun Qiu Zhenjun (長春丘真人), the founder of the Longmen branch in the Yuan dynasty. This book elucidates the principle of the unity of the Three Teachings and transmits the method of cultivating both nature and destiny” (

Y. Liu 2015, p. 443). Moreover, in his process of integrating the Three Teachings, Liu Yiming actually sought to unify them all under the principles of

Neidan; this is why he regarded the “mysterious pass—the single aperture” as the common root for becoming a sage, a Buddha, or an immortal.

Finally, Liu Yiming also merged the

He tu and

Luo shu into a unified system (

Figure 7) because although the contents reflected by the two are different, they are closely related. As he stated:

The He tu is circular in form, signifying the union of yin and yang, the Five Elements as one qi, and the path of non-action, following the natural way of spontaneous generation. The Luo shu is square in form, with an intricate interplay of yin and yang, the mutual restriction among the Five Elements, and the path of action, involving reversed movement and transformative change.

Thus, in Liu Yiming’s alchemical system, the

He tu and

Luo shu, respectively, reflect the images of spontaneous generation and reversal towards immortality, corresponding to non-action and action. By studying the symbols of the

He tu and

Luo shu, one can understand the foundations of the alchemical path. Liu Yiming believed that the differences between the

He tu and

Luo shu were also reflected in the levels of spiritual cultivation: the non-action of the

He tu corresponded to people of superior virtue, while the action of the

Luo shu pertained to those of middling and lower virtue. He said: “Non-action corresponds to pure

yang (純陽) not yet broken, and is practiced by people of superior virtue. Action comes into play after the post-heaven state has arisen, and is practiced by those of middling or lower virtue” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 14). Thus, people of superior virtue possess a unity of nature and destiny and therefore do not require special cultivation—simply nurturing themselves with their innate true fire is enough to attain immortality. However, for those of middling or lower virtue, influenced by post-heaven habits, their nature and destiny become separated. This is why sages created the

He tu and

Luo shu, to provide guidance for those cultivating alchemy.

In summary, compared with the A Brief Commentary on the Xiyi (羲易注略), the Figures in True Explanation of the “Changes.” are more detailed and provide a more intuitive reflection of the cosmological process described in Book of Changes studies. In particular, the application of the Pre-Heaven and Post-Heaven theories and their representation in Figures demonstrate that Liu Yiming was consciously integrating the principles of the Book of Changes directly with those of Neidan. In other words, incorporating the cosmological theory of qi transformation, the concept of the “mysterious pass—single aperture,” and the theories of nature and destiny into the cosmological vision of the yi is one of the ways in which Liu Yiming established a metaphysical foundation for the Daoist alchemical path.

3. The Principles of Neidan Cultivation in True Explanation of the “Changes”

After describing the cosmological process as depicted in the He tu and Luo shu Figures, Liu Yiming proceeded to use the principles of the Book of Changes to elaborate on the foundational principles of Neidan cultivation.

First, he applied the sequence of Fu Xi’s arrangement of the trigrams to create the Figure of Generation from Non-Being to Being (無中生有圖) (

Figure 8). He says:

Utter emptiness and non-being, that is, the Supreme Ultimate (○). What is called ‘the nameless, the beginning of Heaven and Earth’ refers to this void and formless Supreme Ultimate. Yet this Supreme Ultimate is not lifeless, but dynamic and vital; within it lies a concealed spark of vitality (Φ). This vital force is known as the Pre-Heaven True One qi, which is the root of human nature and life, the source of creation, and the basis of life and death. Within emptiness resides this One qi; it is neither being nor non-being, neither form nor emptiness—vividly dynamic, and thus also called ‘true emptiness.’ True emptiness is emptiness that is not empty, and non-emptiness that is empty—the so-called ‘the named, the mother of all things.’ Since there is a spark of vitality within emptiness, the Supreme Ultimate contains the One qi, and from the void, essence begins to manifest.

Clearly, Liu Yiming believed that Supreme Ultimate, as the fundamental entity, is not static but vibrant with life. This living basis, which is also the root of nature and life, is what he referred to as “Pre-Heaven True One

qi” (先天真一之氣). This “Pre-Heaven True One

qi,” as noted by scholars, is an intermediary that Liu Yiming posited between Dao and the cosmos and all things, reflecting his cosmology of

qi transformation—regarding the Pre-Heaven True One

qi as the direct creator of all things (

N. Liu 2000, p. 81).

qi has movement and stillness, just like the

yin and yang, and from these arise nature, emotions, essence, and spirit, corresponding to the Four Images (

si xiang 四象), which then further generate their own respective dynamic and quiescent aspects, thus forming the Eight Trigrams (

ba gua 八卦). In this way, the

Book of Changes cosmological theory of “Supreme Ultimate generates the Two Modes (

liang yi 兩儀), the Two Modes generate the Four Images, the Four Images generate the Eight Trigrams” is completely incorporated into the principles of

Neidan. Therefore, practitioners of immortality seek to comprehend this path of transformation, and through cultivation, are able to transcend life and death, attaining the ranks of the immortals.

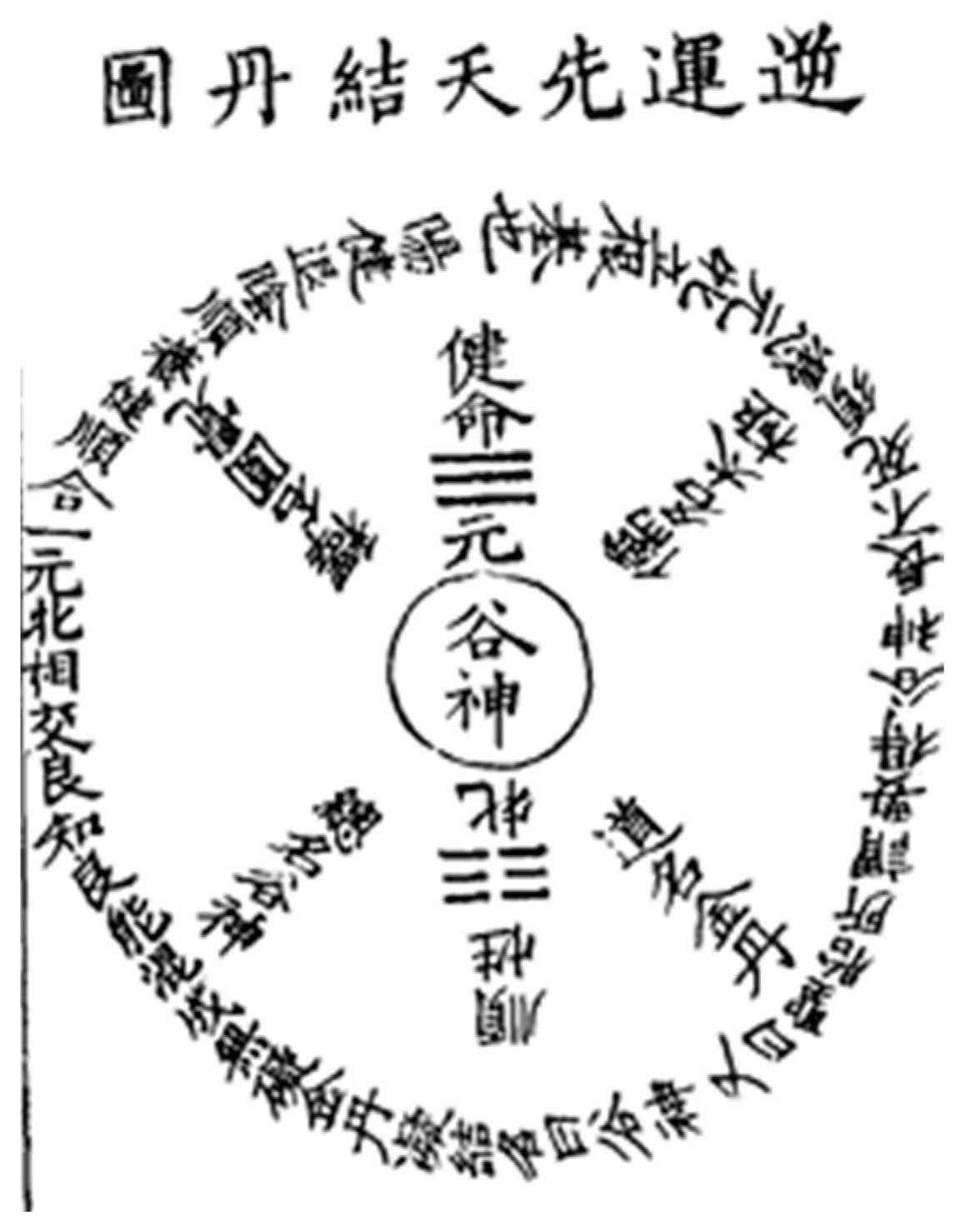

Next, Liu Yiming transforms the Figure of the Eight Trigrams Directions (八卦方點陣圖) (

Figure 9). He states: “The square and round Eight Trigrams, intersecting to form sixteen trigrams, with the center point (¤) at the intersection representing the Supreme Ultimate, which serves as the gateway for the entry and exit of

yin and yang. Both

yin and yang are born here; the Four Images are united here; the Five Phases cluster together here” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 22). This Figure is a circular one that radiates outward from a central circle. Building on this, Liu Yiming creates the Figure of Mixed Pre-Heaven

Yin and yang (先天陰陽混成圖) (

Figure 10) and the Figure of Reverse Circulation and Elixir Formation in the Pre-Heaven Sequence (逆運先天結丹圖) (

Figure 11) In these Figures, “Primordial Feminine” (

yuan pin 元牝) and “Valley Spirit” (

gu shen 穀神) occupy the center, symbolizing the Supreme Ultimate. He says:

The One is the Pre-Heaven True One qi, which is the undivided qi of mixed yin and yang, the qi in which nature and life are condensed and not scattered. … This is called the ‘Valley Spirit.’ This spirit presides over all phenomena and holds sway over yin and yang. The so-called ‘Valley Spirit never dies’—this is called the Primordial Feminine. The gate of the Primordial Feminine is called the root and heart of Heaven and Earth.

Both “Primordial Feminine” and “Valley Spirit” are concepts from the Daodejing (道德經). Here, Liu Yiming regards them as the fundamental root of all things; thus, they are not only the origin of pre-celestial beings but also the destination to which all things return in the reversal process.

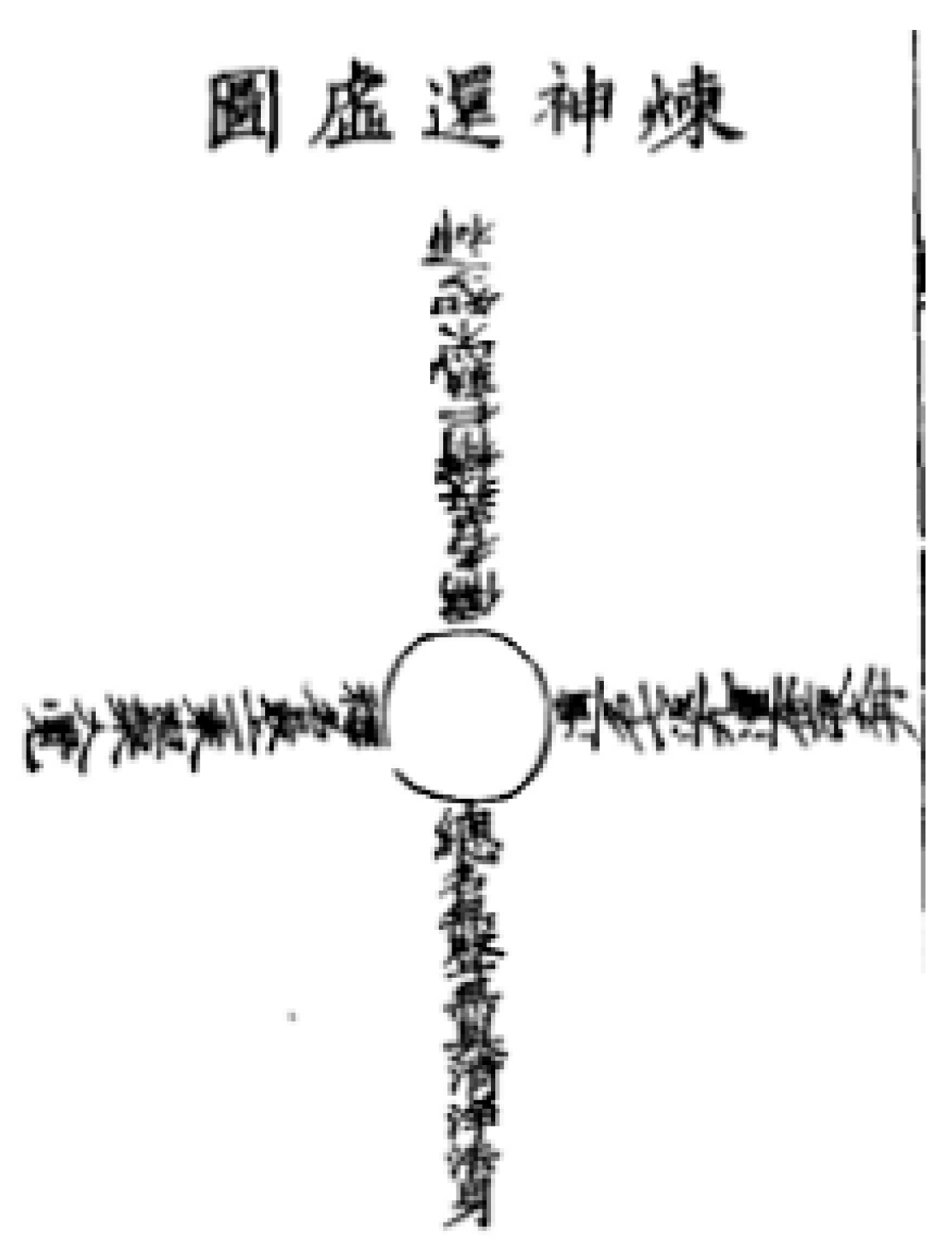

Liu Yiming further decomposes the arrangement of the Eight Trigrams Direction Figure into a square Figure (

Figure 12). He believes that the intrinsic meaning conveyed by the circular Figure and the square Figure is identical, stating:

As for the ‘valley,’ in the circular Figure, it is the empty space between Qian-Heaven (Qian 乾) and Kun-Earth (Kun 坤); in the square Figure, it is the division at the intersection of the cross; in the human body, it is the place where the Four Images are harmonized. As for the ‘spirit,’ in the circular Figure, it is the place where Qian and Kun interact; in the square Figure, it is the point where the cross intersects; in the human body, it is the place where the Four Images move and merge.

Clearly, whether in the circular or the square Figure, the “Supreme Ultimate” always occupies the central position. In the context of the human body, the “Supreme Ultimate” is manifested as the merging of movement and stillness within the Four Images.

Furthermore, Liu Yiming applies the concept of the “center” (

zhong 中) of the Supreme Ultimate to

Neidan and thus creates the “Figure of the Center” (中圖) (

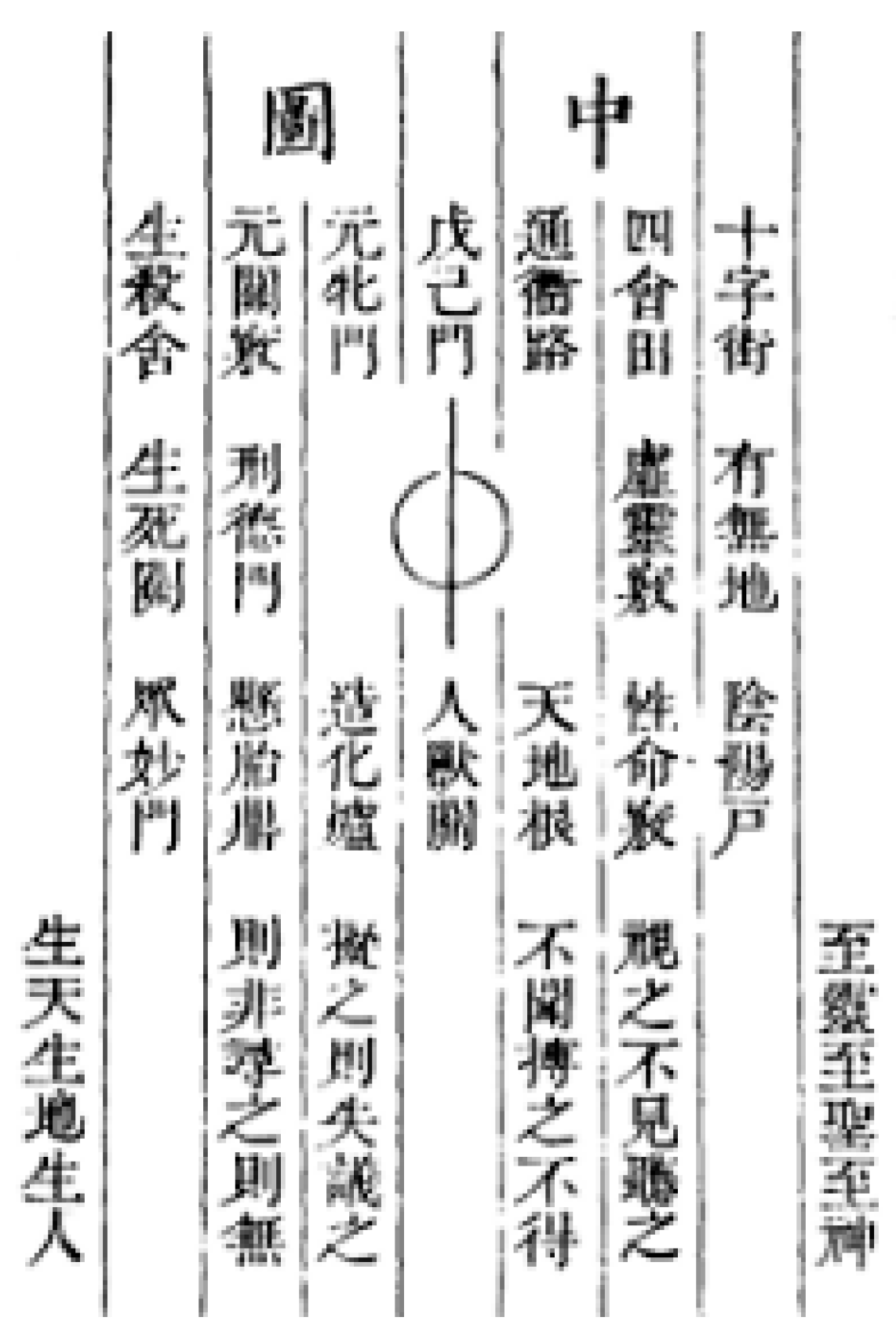

Figure 13) to explain this. He says:

Confucianism speaks of ‘holding to the center’ (zhi zhong 執中), Daoism speaks of ‘keeping to the center’ (shou zhong 守中), and Buddhism speaks of ‘emptiness at the center’ (xu zhong 虛中) The single character ‘center’ is the heart-method of the sages of the three teachings. Thus, the cultivation of nature and life to attain the Great Dao, across thousands of scriptures and classics, ultimately comes down to this one character. In seal script, the character ‘zhong’ is composed of ‘○’ and ‘│’: in the human being, this is the innate virtue, perfect goodness without evil, a clarity that is never obscured—what is called the Pre-Heaven True One qi. The ‘○’ contains the ‘│’, which signifies the seamless natural principle, the one qi flowing up and down, endlessly circulating. Moreover, the ‘│’ is at the very heart of the ‘○’; the left of the ‘○’ is yang, the right is yin, just as in the Hetu Figure, the left is yang, the right is yin, representing the one qi moving between above and below”

From the perspective of etymology, the character “

zhong” is composed of “○” (the circle, representing Supreme Ultimate) and the vertical line “│” (symbolizing the Pre-Heaven True One

qi that penetrates above and below). At the same time, “center” is also the source of both nature and life in

Neidan, as he writes,” This ‘center’ is the root of nature and life. In the Pre-Heaven state, nature and life are unified as the center

![Religions 17 00059 i001 Religions 17 00059 i001]()

(

xing-ming 性命); in the Post-Heaven state, the center splits into nature and life

![Religions 17 00059 i002 Religions 17 00059 i002]()

(

xing zhong ming 性中命). In truth, when the Post-Heaven state returns to the Pre-Heaven state, nature and life are re-united, and both ultimately return to the one center” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 32).

This division also makes it possible for the Post-Heaven to return to the Pre-Heaven, because the “center,” as the root of nature and life, runs through both states; thus, humans are able to attain the Dao and become immortals. The process of this return is what the alchemical classics call the “seven reversals and nine returns” (七返九還). More importantly, there are often misconceptions about the “center,” which can easily lead people astray. Therefore, Liu Yiming uses interpretations from the three teachings to point out that the “center” does not refer to any specific thing, but rather to a kind of state or realm. Thus, attaining the “true center” is like returning to one’s birthplace—it is the true homeland.

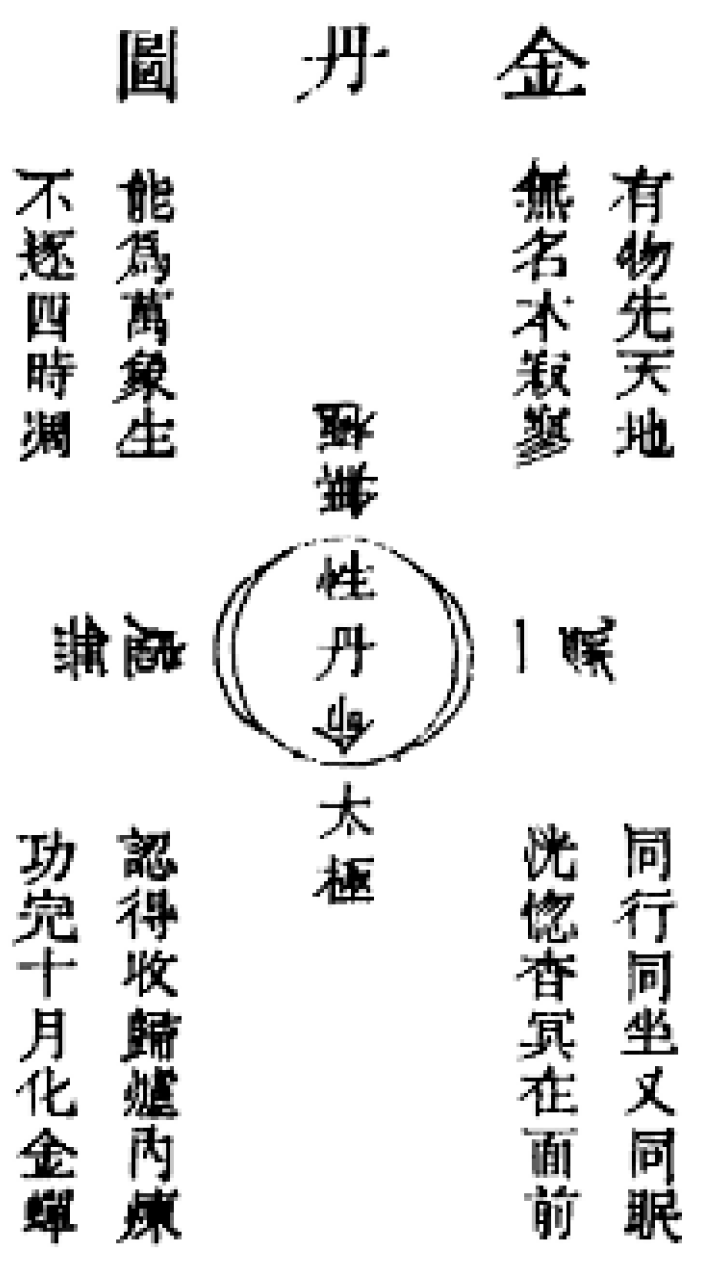

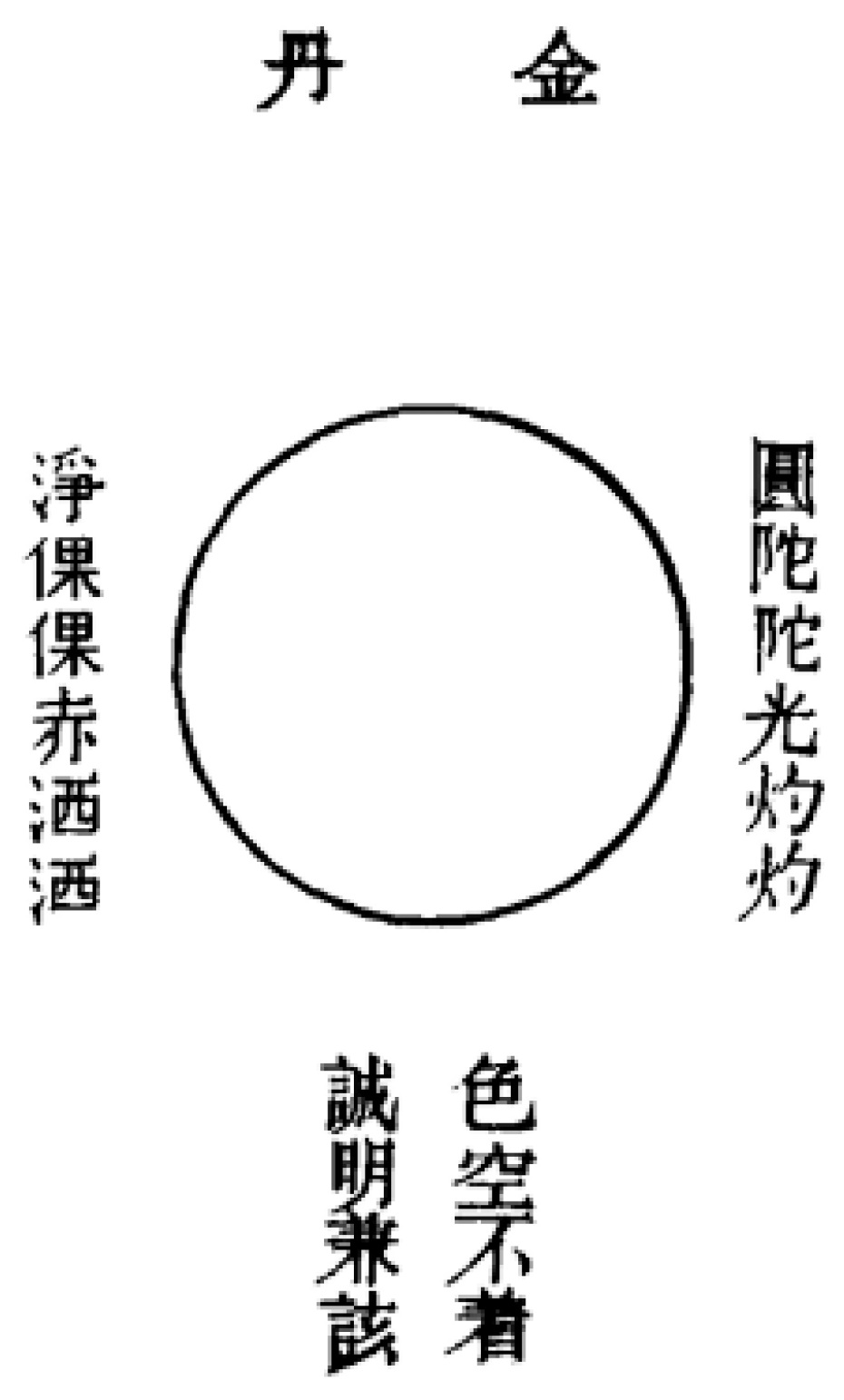

Since the “center” is the source of both nature and life, understanding the meaning of “center” allows one to arrive at the Figure of the Golden Elixir (金丹圖) (

Figure 14). Like the concept of “center,” Liu Yiming believes there are common misconceptions among people regarding the Golden Elixir. Thus, he says, “Those who seek the Dao are as many as ox hairs (

niu mao 牛毛), but those who attain the Dao are as rare as the horns of a unicorn (麟角)” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 33). This, in fact, explains why, throughout history, so few cultivators have become immortals: although dedicated practitioners have never been lacking, those who ultimately achieve immortality are exceedingly rare, leading people to sometimes doubt the reality of

Neidan. Liu Yiming attributes this situation to misunderstandings about alchemy, thereby emphasizing the uniqueness of his own teachings.

As for the meaning of the Golden Elixir, he says: “Gold (

jin 金) signifies firmness and indestructibility; elixir (

dan 丹) signifies roundness and fullness without deficiency. The elixir is the innate Pre-Heaven True One

qi (先天真一之氣). This

qi, having undergone refining by the fire, endures countless trials and never perishes—this is why it is called the Golden Elixir” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 33). In his view, the name Golden Elixir expresses its eternal and perfect qualities. “Eternal” means that the Golden Elixir has always existed, neither arising nor perishing; “perfect” means that once a person attains this elixir, they can cultivate to become an immortal and achieve complete fulfillment. Furthermore, the Golden Elixir originates from the “Pre-Heaven True One

qi,” and so it remains undamaged no matter how much it is tempered.

In summary, Liu Yiming expounds the Dao of Neidan (丹道) through the principles of the Book of Changes, employing Figures from the Book of Changes and transforming them into alchemical Figures, thus establishing the metaphysical foundation of alchemy upon the Dao of Change. The use of images makes the complex process of alchemical cultivation more concrete and renders the profound theoretical concepts of alchemy easier to understand.

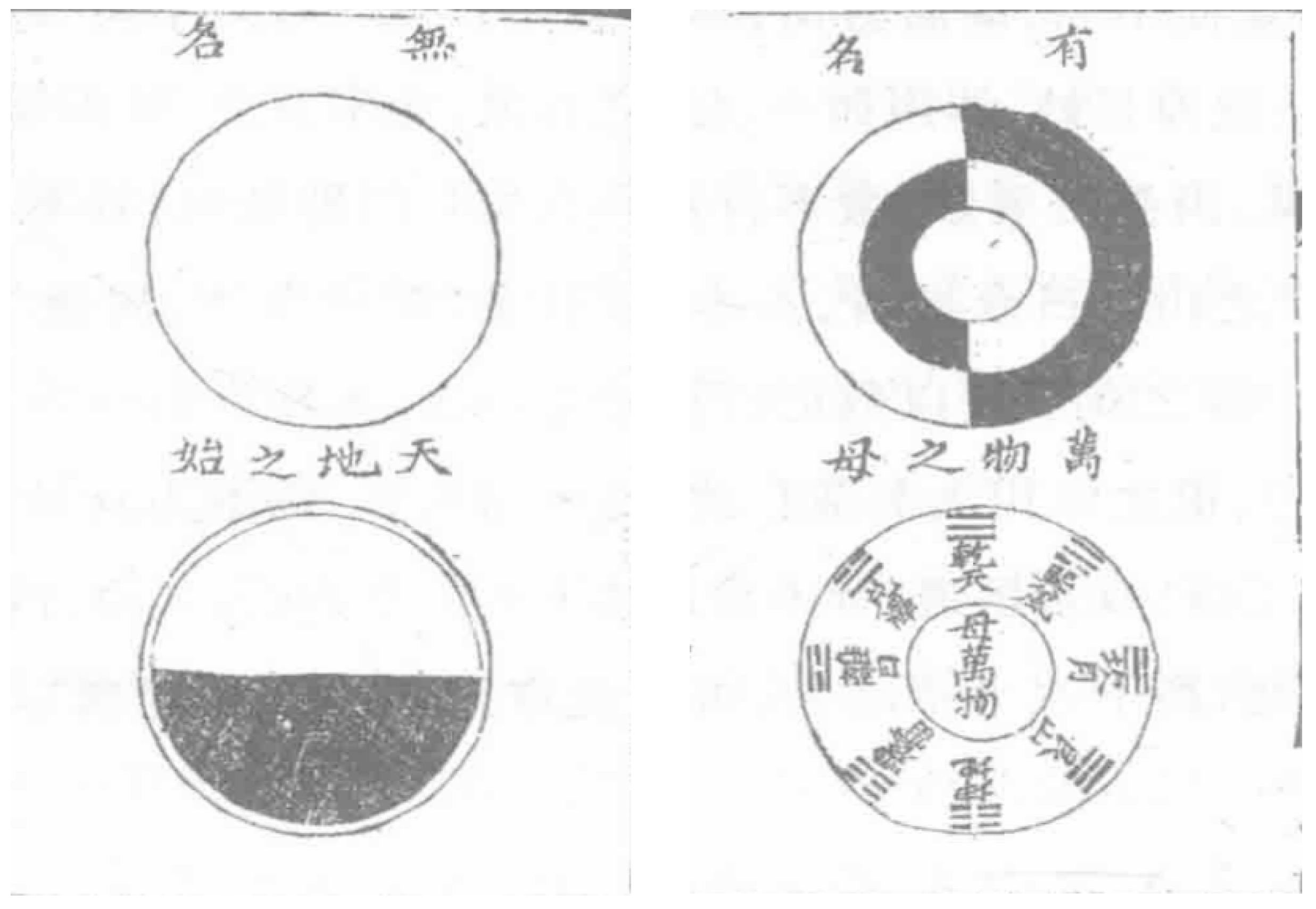

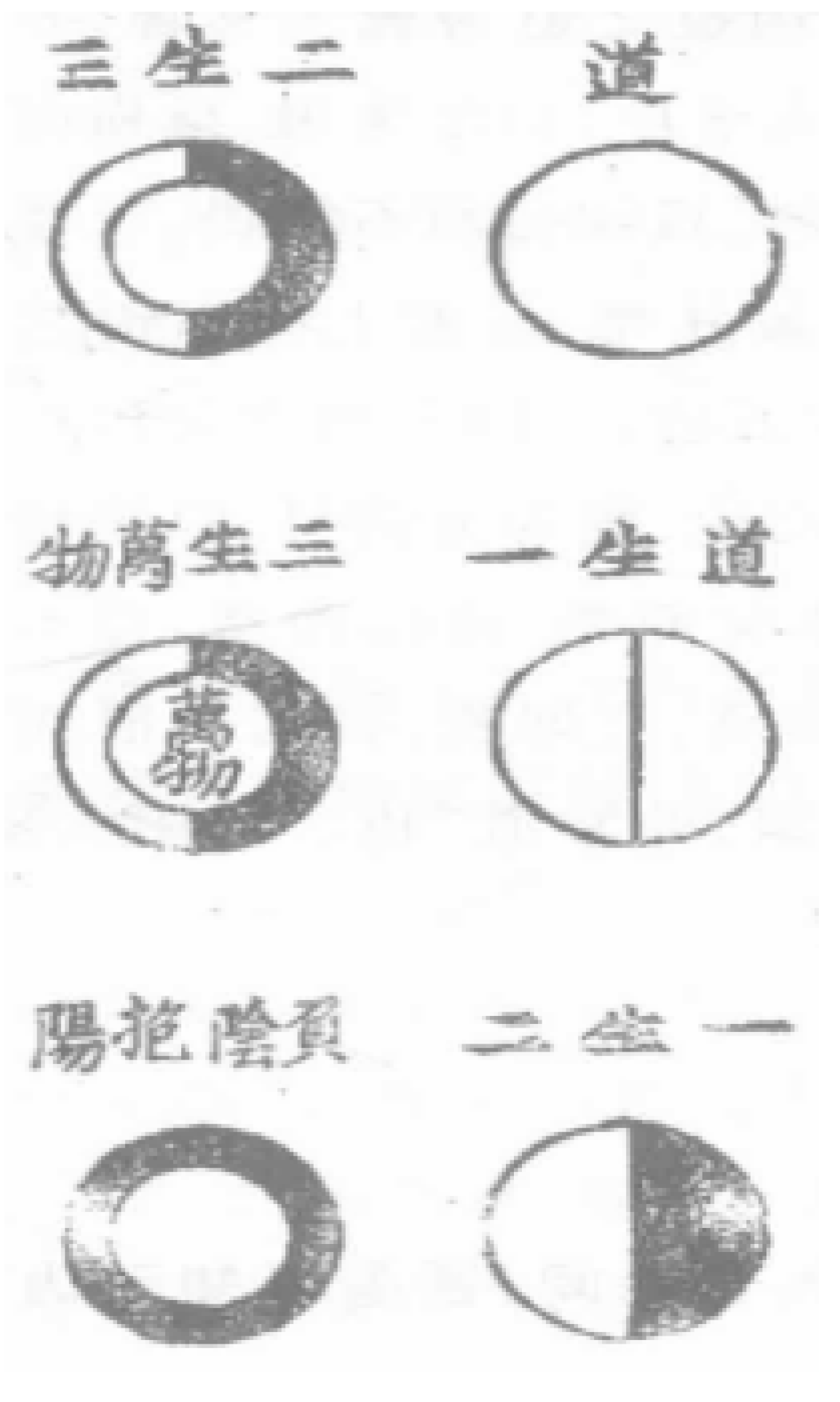

4. The Theory of Alchemical Genesis in The Meaning of the Daodejing

As the founder of Daoism, “Laozi has for centuries been linked with change, transformation and the alchemical tradition” (

Baldrian-Hussein 1989, p. 174). In addition to using

Book of Changes Figures to illustrate the metaphysical foundation of alchemy, Liu Yiming also employs imagery to present Laozi’s theory of cosmic genesis, likewise regarding it as a metaphysical basis for the Dao of

Neidan. In his work

Daodejing huiyi, Liu Yiming integrates the doctrines of the

Book of Changes and Laozi, representing the concepts of “nameless” (

wu ming 無名) and “named” (

you ming 有名) with the Figure of Two Modes and Four Images (二儀四象圖) (

Figure 15) He states:

At the very beginning of heaven and earth, there were absolutely no forms or traces; although the qi of the Dao existed, the name of the Dao had nowhere to be established. When this ○ Dao-qi moves, yang is born: pure qi floats upward to become heaven—this is Qian ☰. When it becomes still, yin is born: turbid qi sinks downward to become earth—this is Kun ☷. Above is heaven and below is earth; when Qian and Kun are established in their positions, what takes form in heaven are the sun, moon, and thunder—these are Li ☲, Kan ☵, and Zhen ☳; what takes form on earth are mountains, lakes, and wind—these are Gen ☶, Dui ☱, and Xun ☴.

In this way, the process of the Dao’s generation is, in fact, the process of genesis as explained by the Book of Changes. This connects the “Dao” and the eight trigrams, thus making it possible to interpret the Daodejing from the perspective of Neidan.

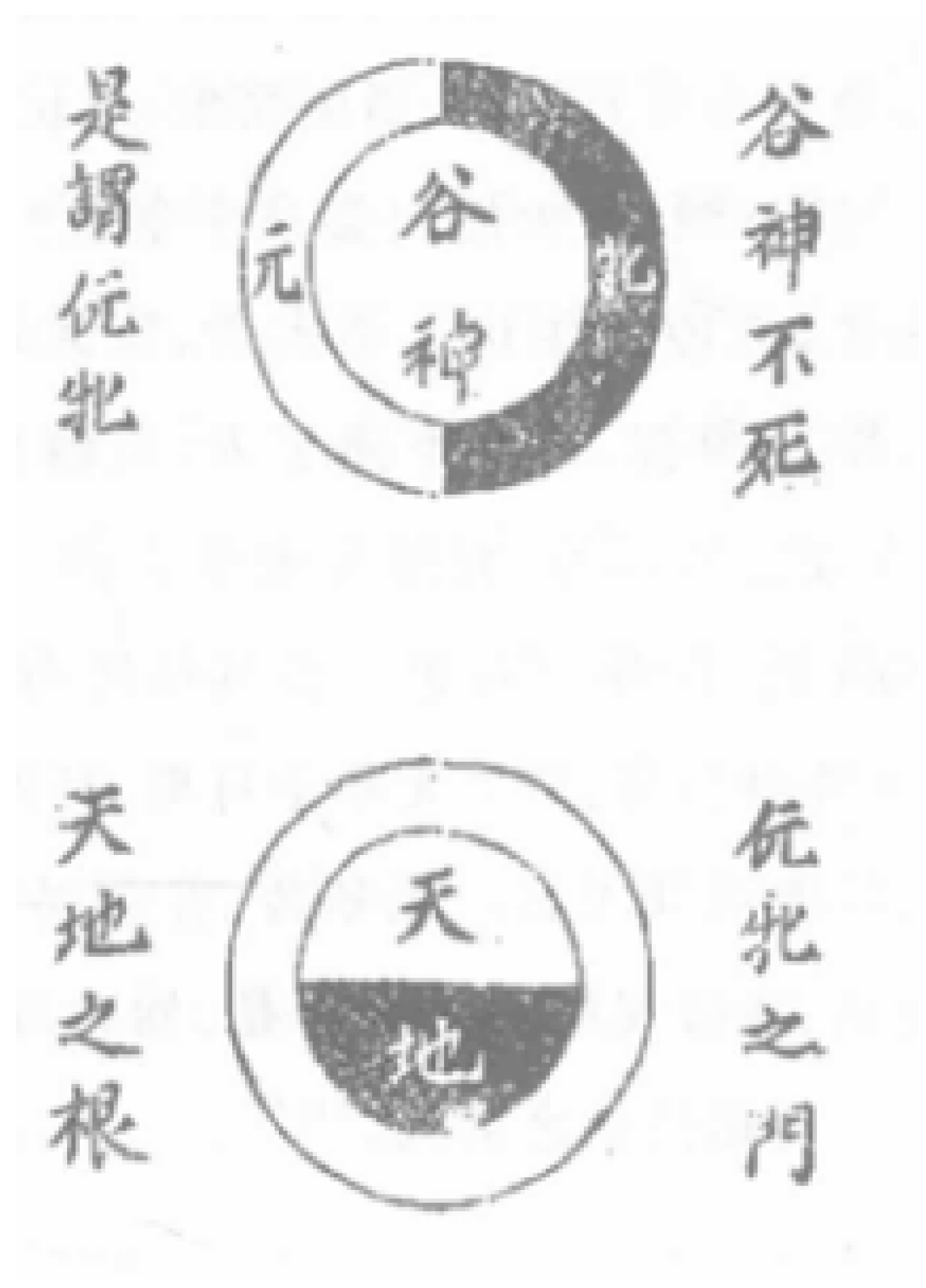

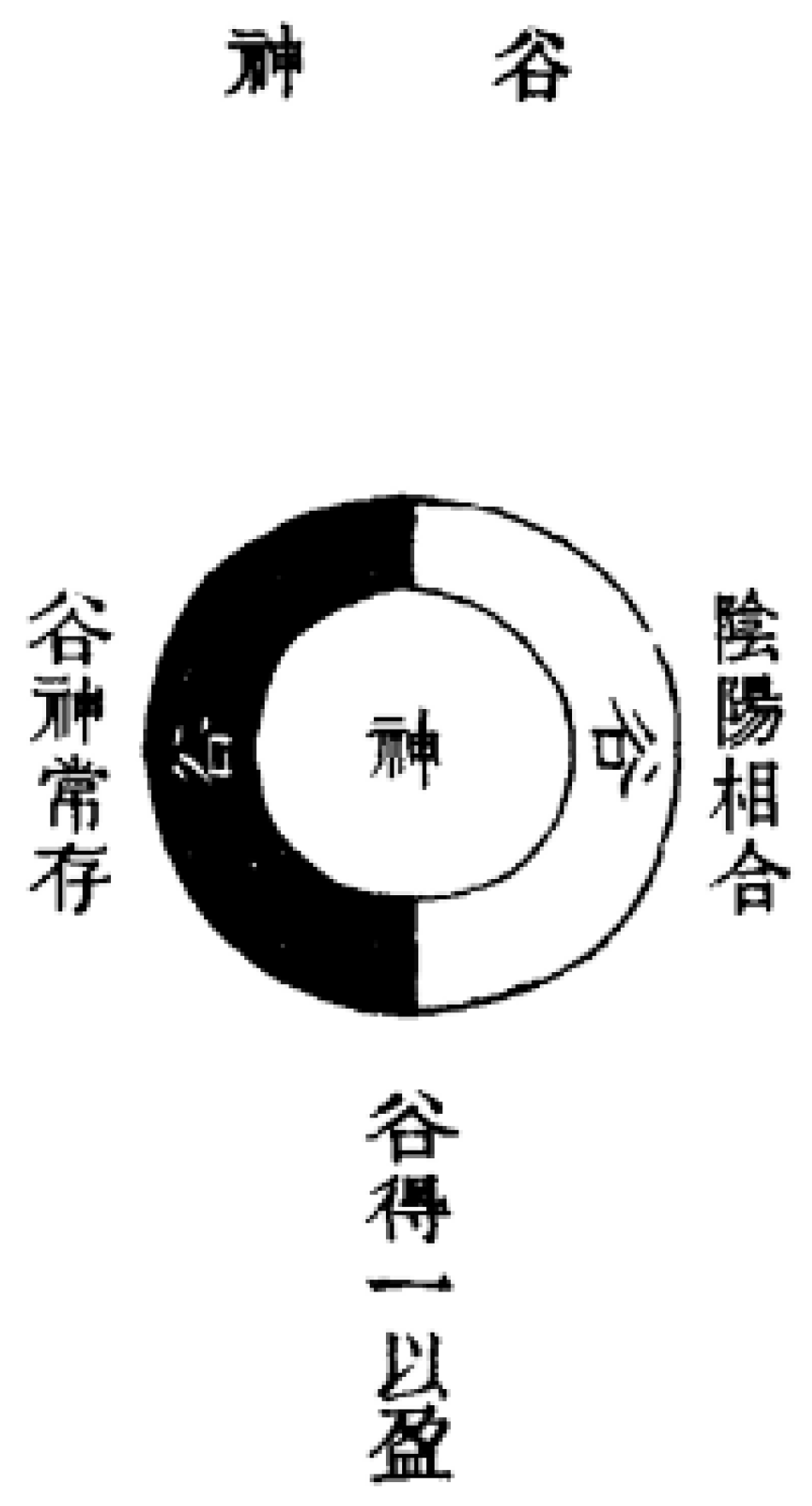

In addition to concretizing the concepts of nameless and named, Liu Yiming placed particular emphasis on the significance of the Valley Spirit, for which he created the Figure of the Valley Spirit (穀神圖) (

Figure 16). This is because Laozi said, “The Valley Spirit never dies; this is called the Mysterious Female. The gate of the Mysterious Female is called the root of heaven and earth.” The notion of never dying thus became the goal pursued by generations of immortality seekers. In fact, Daoism records “many metaphos about death recorded in the scriptures” (

Geng 2024, vol. 15, pp. 2, 1482). Death and immortality have always been key concepts in Daoist cultivation.

As for what the Valley Spirit means, Liu Yiming explains:

The Valley Spirit is truly empty yet harbors wondrous existence; wondrous existence yet contains true emptiness. It is utterly still and unmoving, yet responds when stimulated. In movement and stillness, they support each other and are each other’s root—this is called the Valley Spirit never dying. That which never dies is due to being able to move and be still. Because it does not die, there is movement and stillness—this is the yang mystery and the yin female emerging from the human gateway.

Clearly, in his interpretation of the Valley Spirit, Liu Yiming draws from the Buddhist doctrine of true emptiness and wondrous existence, as well as the stillness and response theory from the

Book of Changes, to explain its fundamental nature. In this way, “the Valley Spirit never dies” becomes one of the main theoretical bases for the realization of immortality in alchemy. Valley Spirit is also a symbol of the inner gods, according to Taoist thought, “the inner gods perform multiple roles related to one another: they allow the human being to communicate with the corresponding gods of the celestial pantheon, serve as administrators of the human body and guard the balance of the body’s main functions” (

Pregadio 2021, p. 110).

In addition to the “Valley Spirit” Figure, Liu Yiming also visualized the Dao generates chapter from the

Daodejing (

Figure 17), thereby illustrating Daoism’s unique cosmological theory of creation. He said:

Thus, the Dao, from emptiness and nothingness, gives rise to the One qi. The One qi is the beginning of number, the mechanism of generation—this is the Dao. The Dao itself is invisible; it is made manifest through the creation of things. The Dao originally has no number, but because it generates things, it becomes One; One is simply the name of the Dao.”

In this way, Liu Yiming used a set of Figures to present the cosmological vision of creation in Daodejing. Among these, the “Three Generates the Myriad Things” Figure and the “Valley Spirit” Figure share the same structure: both are composed of two concentric circles, with the outer ring divided into two parts, representing yang and yin, respectively. Clearly, such Figures not only concretize Laozi’s cosmology but also connect it to the theory and practice of Neidan. In this cosmological and alchemical system, “qi” occupies a crucial position—that is, the Dao itself is the formless one qi (虛無一氣), and all things are generated through the transformation of qi.

In fact, this cosmological view of the transformation of

qi can be traced back to the pre-Qin philosophers Laozi and Zhuangzi. In Laozi’s vision of cosmic creation,

qi is a crucial component. He said, “The Dao gives birth to One; One gives birth to Two; Two gives birth to Three; Three gives birth to the myriad things. All things carry yin and embrace yang, and the blending of

qi brings harmony” (

Wang and Lou 2008, p. 117). Zhuangzi inherited and further developed Laozi’s theory of

qi. In the

Zhuangzi, not only is

qi emphasized as the element that constitutes all things, but its universality throughout the cosmos is also strongly asserted: “Human life is a gathering of

qi. When it gathers, there is life; when it disperses, there is death. … Thus, it is said: ‘All under Heaven is but one

qi’” (

Guo and Wang 2013, p. 647).

It is clear, then, that as the fundamental element forming the universe, “

qi” is the reason for the life, death, gathering, and dispersal of all beings, including humans; thus,

qi is also regarded as the source of the physical forms of all things. The Zhuangzi states, “If we examine the beginning, there was originally no life; not only was there no life, there was no form; not only was there no form, there was no

qi. Mixed within the vague and indistinct, transformation brings about

qi;

qi transforms and produces form; form transforms and gives rise to life. Now, through further transformation, there is death” (

Guo and Wang 2013, p. 546). This presents in detail the process of the emergence of life: from “

qi” to “form” (形) then to “life” (生) showing that life and death are, in essence, transformations of “

qi.” Later, this Daoist cosmology of the transformation of

qi was incorporated into the practice of alchemy, becoming one of the three essential substances in

Neidan.

5. The Principles of Alchemy in Xiangyan Poyi

After discussing various metaphysical foundations of alchemy, Liu Yiming shifted his focus to the practical aspects of alchemical cultivation. Given that many people of his time misunderstood the practice of alchemy, and that its teachings were often obscure and difficult to comprehend, he wrote

Xiangyan poyi with the aim of clarifying and correcting these misconceptions. More importantly, consistent with his argumentation regarding the metaphysical foundations of alchemy, Liu Yiming also attached great importance to the use of images in this work. This is because he consistently believed that the core of alchemy lies in imagery. As he stated in the preface:

All the myriad volumes of alchemical classics employ symbolic language. Symbolic language is neither direct speech, nor explicit speech, nor empty words, nor strange words; rather, it is speech that is grounded in actual things and established patterns, with clear indications and evidence, using images to express the truth. Later generations, failing to grasp its intent and sticking only to the outward forms, have led Confucian scholars who read them to regard these texts as fanciful and unorthodox, and Daoist practitioners to view them as mere superficial forms. Some even cling to these symbols with suspicion, engaging in all sorts of contrived practices and deviant paths, thereby harming their own lives—such cases are too numerous to count.”

It is thus evident that Liu Yiming believed all alchemical scriptures (

Dan jing 丹經) were written in symbolic language, which means using images to elucidate the principles of alchemy—that is, as he said, “An image (

xiang 象) is a likeness. One speaks of this thing by referencing another, or of this matter by referencing that” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 172). This concept of “observing things to derive images” and “the mutual resonance among categories of things” can be regarded as one of the fundamental ideas in Chinese philosophy. According to tradition, the eight trigrams of the

Book of Changes were formulated by King Wen 文王 following this very principle of “drawing parallels from the body nearby and from external things far away.” At a deeper level, behind “observing things to derive images” lies the thinking method of “the unity of Heaven and humanity” (

tianren heyi 天人合一) In Daoism, this concept is expressed in the idea that the human body is a microcosm of the universe, so alchemical practice can also be represented through images. Thus, what these “images” reflect is the underlying “principle” (

li 理) behind them, and the study of “images” is essentially the study of the principles of alchemy. Liu Yiming said, “The alchemical scriptures all use images to explain principles, teaching people to discern the principle behind the practice by means of images, not to encourage people to ignore the principles and become entangled merely with the images themselves” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 173). It is precisely for this reason that Liu Yiming was able to refute the view that alchemical writings are “fantastical and absurd” (

guaidan bujing 怪誕不經) or “mere superficial imagery” (

baopi waixiang 包皮外象)—this is the essence of “dispelling doubts”.

After establishing the method of elucidating “principles” through “images”, Liu Yiming first explains the fundamental theories of alchemy. In particular, he provides a relatively systematic exposition of the three core principles: the forward and reverse processes, the doctrine of medicinal substances, and the doctrine of timing and regulation of fire. Thus, he concludes: “The Way of cultivating reality (

xiuzhen zhidao 修真之道), as found in the thousands of alchemical scriptures and countless classics, is all expressed through symbolic language. Although the specific images employed may differ, their ultimate purpose is to elucidate the principles of the correct and incorrect interplay of

yin and yang (

yinyang nishun 陰陽順逆), the authenticity of the alchemical medicines (

yaowu zhenjia 藥物真假), and the proper regulation of timing and fire (

huohou zhunze 火候準則)—nothing beyond these. Outside of this, there are no other teachings” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 173).

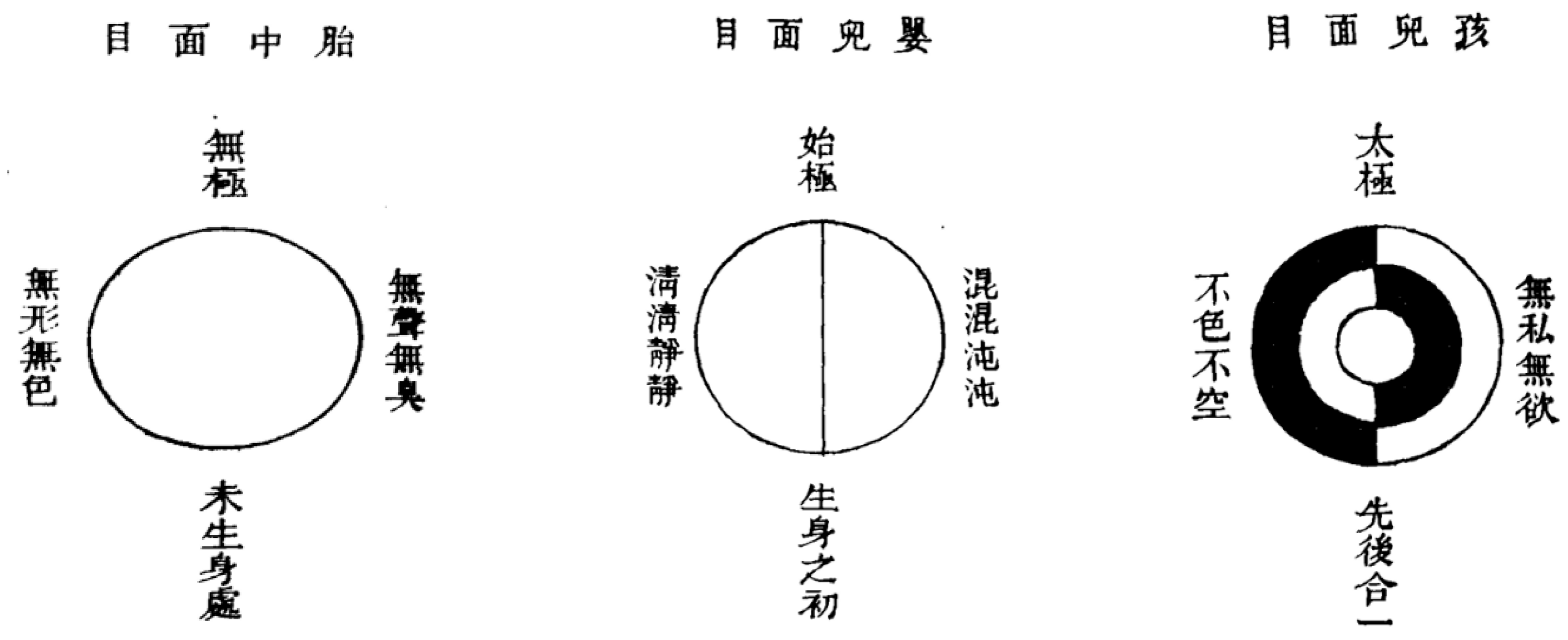

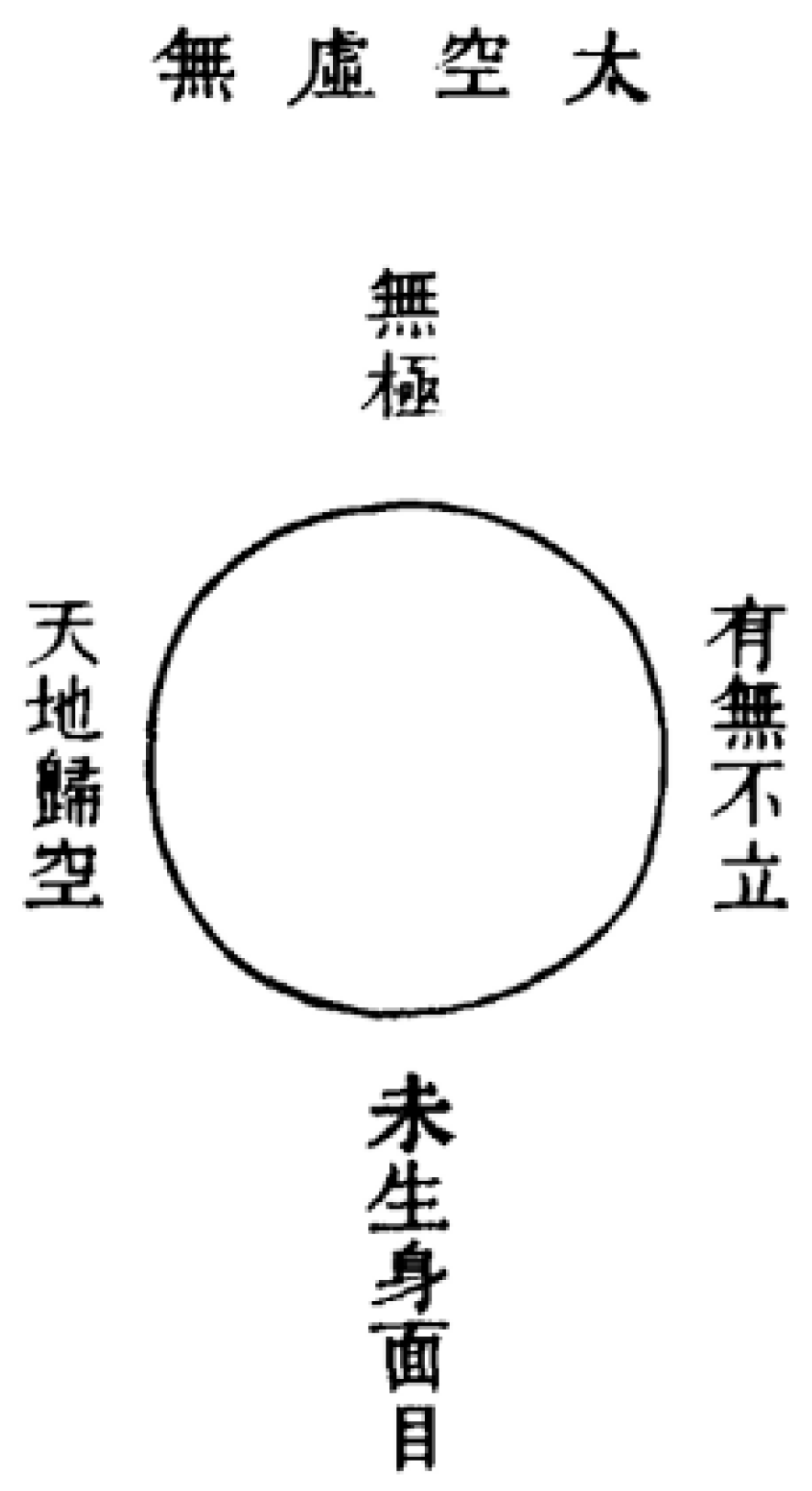

On this basis, Liu Yiming first presents the process of the growth and transformation of the Golden Elixir within the human body (

Figure 18)—that is, the progression from fetus, to infant, and then to child. This process also corresponds to the transformation of the Supreme Ultimate into the Prime Ultimate (

shi ji 始極), and then back into the Supreme Ultimate. Visually, this progression is represented by the transition from the formless and colorless state of the perfected Golden Elixir, to the initial opening of chaos—where a single vertical line “│” divides the Elixir into two—and finally to the mutual coexistence of

yin and yang, and the unification of the innate and acquired states. Unlike previous alchemists, Liu Yiming further distinguishes the state of the Golden Elixir after the fetal stage into “infant” and “child,” considering them as two distinct states. The difference between the two lies in the fact that the infant is devoid of awareness and knowledge, whereas the child possesses cognitive faculties. “Thus, the ancient immortals always regarded ‘returning to the origin and reverting to the source’ as the true state of the infant (

yinger mianmu 嬰兒面目), not the boisterous and playful nature of the child (

haitong mianmu 孩童面目)” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 178). In essence, this also serves as an explanation of the phrase from the

Daodejing (“like an infant who has not yet become a child”), that is, taking the state of the infant—prior to becoming a child—as the true goal of the alchemical path.

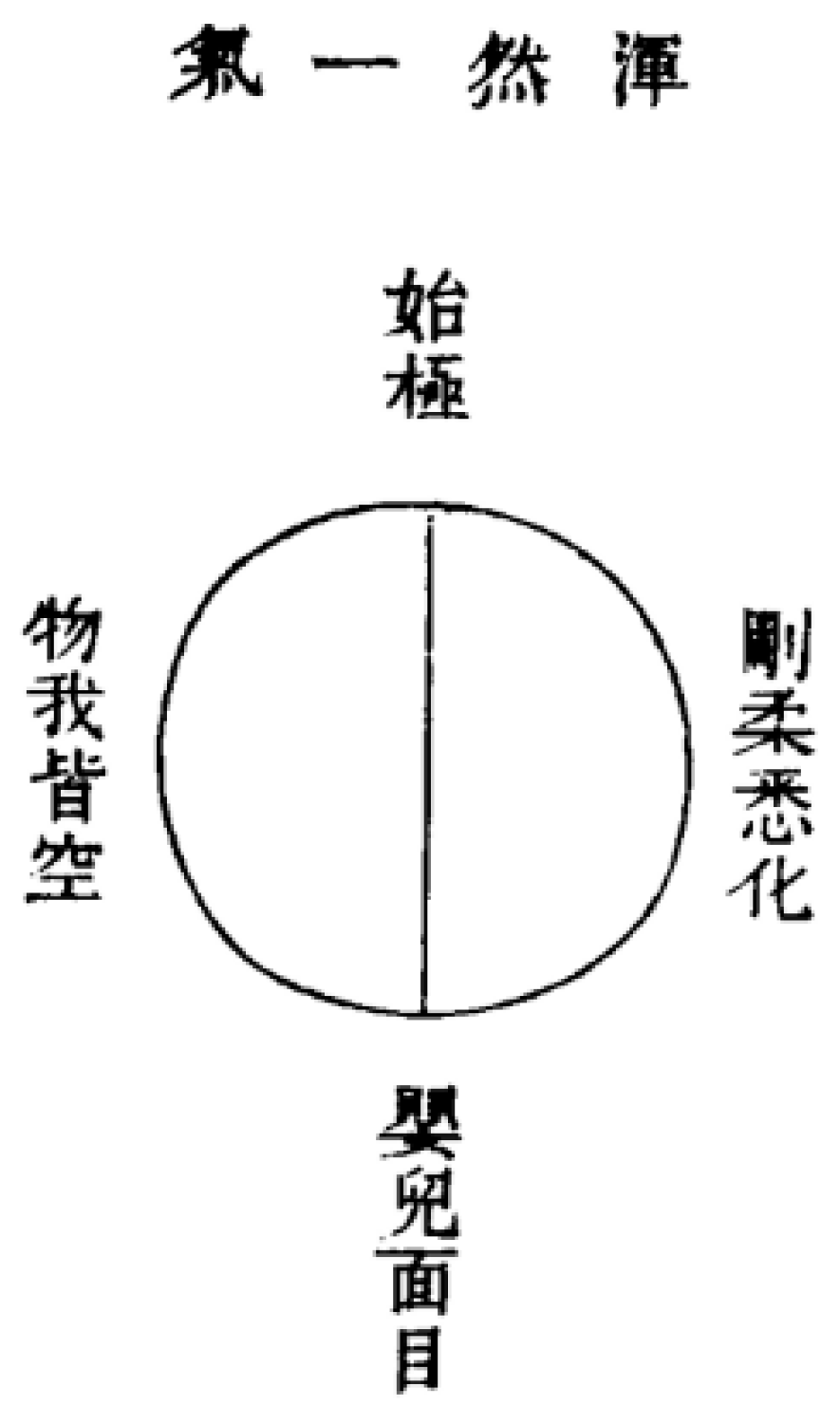

The growth of

yang qi does not mean that

yin qi will immediately and completely disappear. Rather, it reaches a balanced state where

yin and yang are mixed together (

Figure 19), a condition described as “returning to the appearance of a child.” Although this state cannot yet result in the formation of the Golden Elixir, “when the innate is restored and the acquired follows in harmony, there can be no further harm. From this point, after one more stage of refinement, the Golden Elixir can be achieved” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 183). This means that the blending of

yin and yang has already come close to the accomplishment of the Golden Elixir, and with further cultivation from this stage, one then attains the state of “complete unity of

qi” (

hunran yiqi 渾然一氣) (

Figure 20). At this point, a person progresses from the “appearance of a child” further backward to the “appearance of an infant.” Thus, Liu Yiming said: “This gestation is the ‘appearance of an infant,’ the very place where life takes form and receives

qi; it is also the utmost beginning and the Supreme One containing true

qi” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 184). Therefore, returning to the “appearance of an infant (

yinger chuxian 婴儿出现)” is to return to the very beginning of life, to the moment when primordial

qi first takes shape and forms the human being. In visual terms, this state is depicted by the dispersal of

yin and yang, leaving only a single vertical line “│” running through it. At this stage, not only have

yin and yang both vanished, but one has also attained a state where firmness and gentleness are fully transformed, and the distinction between self and the external world is entirely dissolved. Proceeding a step further, the “│” also dissolves, thus entering the state of “great emptiness and void” (

taikong xuwu 太空虛無) (

Figure 21), ultimately returning to the “original face before birth.” In this way, the complete cycle of

Neidan within the human body is accomplished; therefore, as Liu Yiming said: “This is the original face before birth, also the face of

wuji (無極). The Dao returns to

wuji; body and spirit are both wondrous (

xingshen jumiao 形神俱妙), united with the Dao in true reality—thus is the achievement of the great person” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 184). The so-called yang spirit is the deity in charge of the transformations of the Golden Elixir, characterized by its eternal existence and absolute perpetuity. The yin spirit, on the other hand, resides within the human body and, if left unrefined, will perish together with the spirit.

6. Alchemical Imagery in Xiangyan Poyi

Compared with his other works, Liu Yiming’s description of the Golden Elixir (

Figure 22) in

Xiangyan poyi is even more detailed and concrete. In this text, he also provides a definition of the term “Golden Elixir”, stating: “‘Gold’ refers to something solid, firm, and everlasting; ‘Elixir’ refers to something perfectly round, luminous, pure, and without deficiency. The ancient immortals borrowed the name ‘Golden Elixir’ to symbolize the original, complete, and luminous true spiritual nature (本來圓明真靈之性也)” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 185).

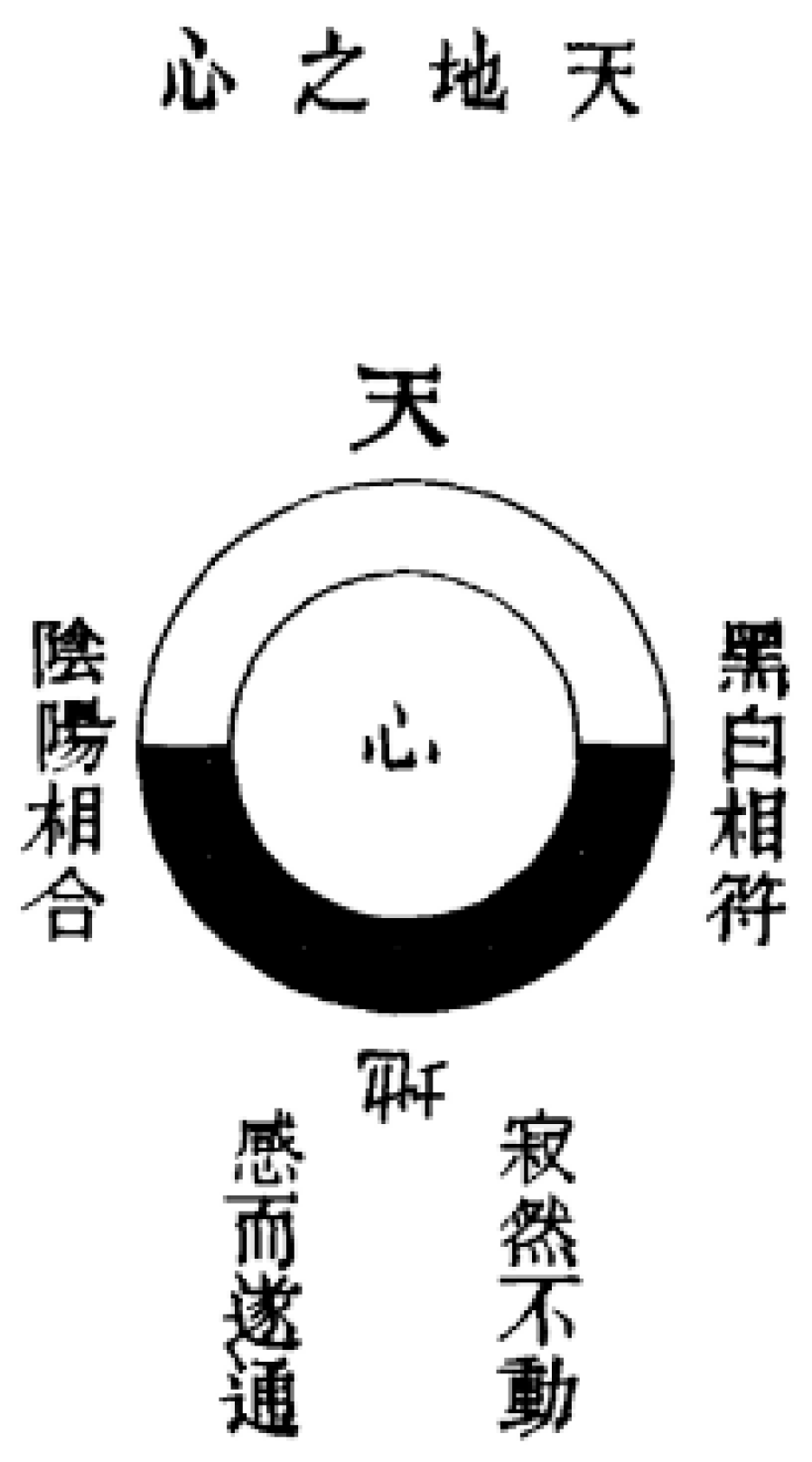

Liu Yiming interpreted the inner meaning of the Golden Elixir through Confucian thought, largely because Neo-Confucianism had already become the mainstream firmly established ideology. For this reason, when discussing the Golden Elixir, he frequently cited Confucian sources as evidence. For example, in his creation of the “Heart of Heaven and Earth” (天地之心) Figure (

Figure 23), the phrase “the heart of Heaven and Earth” originates from the

tuan Commentary on the Fu hexagram in the

Book of Changes, which states: “The return reveals the heart of Heaven and Earth” (

Zhu 2009, p. 110). Liu Yiming regarded this as the primary task in alchemical cultivation. He said:

The first essential in cultivating the Way is to recognize the heart of Heaven and Earth. The heart of Heaven and Earth is precisely what was previously called the innate true mind. This mind is elusive and obscure, rarely manifesting outwardly; only in moments of emptiness and stillness, when a faint light arises out of the darkness, does its true form begin to reveal itself.

Precisely because the “heart of Heaven and Earth” is one’s innate, pure mind, it is only by recognizing this mind that one can begin to refine the Golden Elixir. In the Figure of the “heart of Heaven and Earth,” we can also discern traces of Confucian thought. Specifically, this mind is situated between Heaven and Earth, directly corresponding to the image of the three powers—Heaven, Earth, and Humanity. The phrase “utterly still, yet responsive to stimulus” (

Zhu 2009, p. 238) comes from the

xici (繫辭) commentary of the

Book of Changes; Liu Yiming used this concept to explain how the Golden Elixir, from its fundamentally still and unmoving essence, can dynamically generate the myriad things of Heaven and Earth. This, too, is the very function and efficacy of the Golden Elixir.

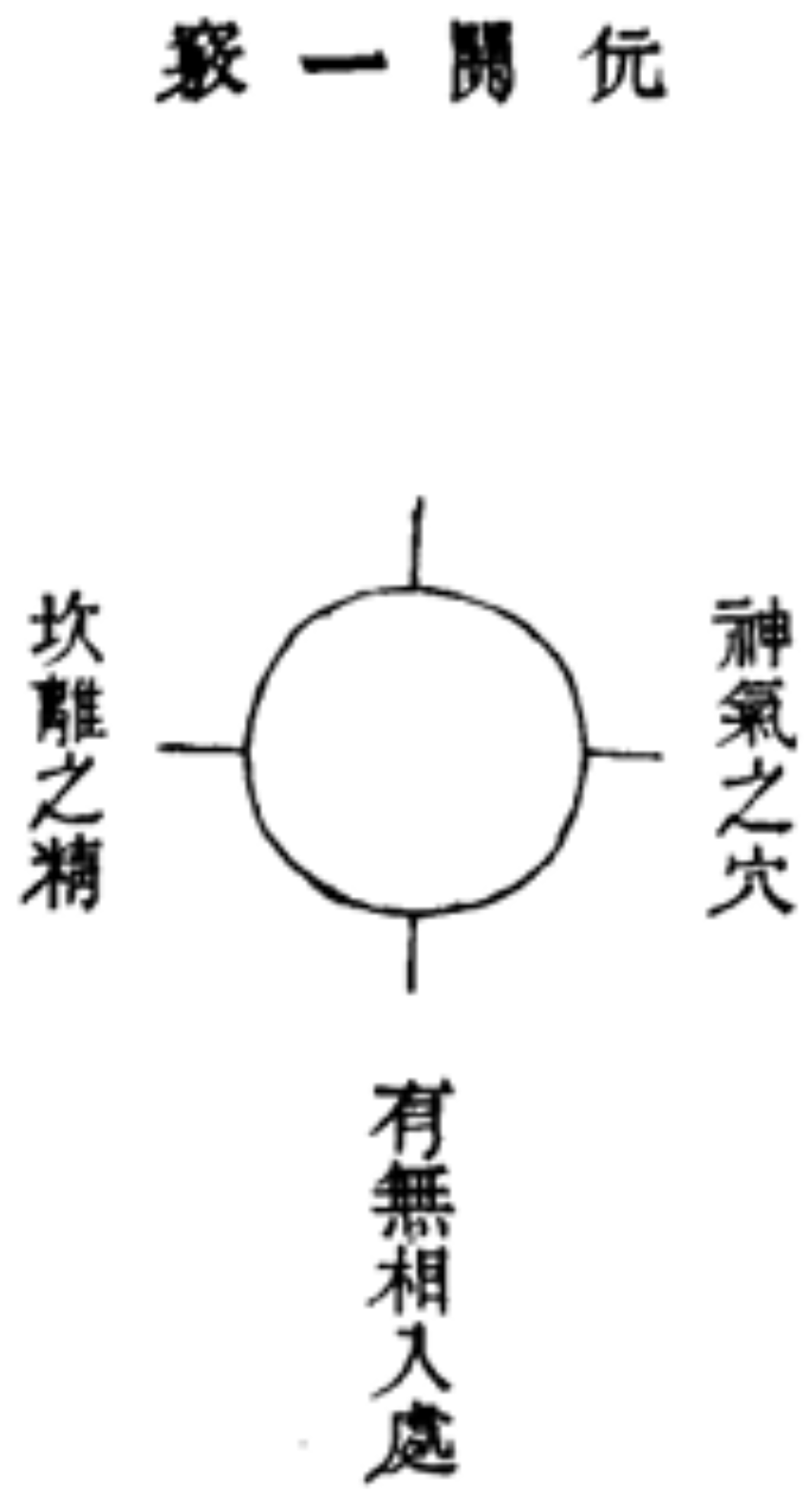

In addition, Liu Yiming illustrated other important concepts related to the process of Golden Elixir cultivation, providing visual references for practitioners. For example, the concepts of “” (

Yuanpin zhimen 元牝之門) (

Figure 24), “the Primal Pass—One Aperture” (

yuanguan yiqiao 元關一竅) (

Figure 25), and “the Valley Spirit” (

Figure 26)—all originate from the

Daodejing. The terms “the Gate of the Mysterious Female” and “the Primal Pass—One Aperture” were modified from the original

xuan (玄) to

yuan (元) to avoid the taboo associated with the Kangxi Emperor’s personal name during the Qing dynasty. Since the establishment of

Neidan, these terms have become key concepts for describing the Golden Elixir. As Zhang Boduan (張伯端) said in the

Awakening to Reality (悟真篇):

Few in this world know the Gate of the Mysterious Female, (玄牝之門世罕知)

Mistaking it for the mouth and nose in vain. (只將口鼻妄施為)

Even if you practice breathing exercises for a thousand years, (饒君吐納經千載)

You cannot make the golden crow catch the rabbit. (爭得金烏攝兔兒)

This shows that the “Gate of the Mysterious Female” refers to the aperture of breathing—the channel through which internal and external

qi interact. “The Primal Pass is another name for the Gate of the Mysterious Female; because

yin and yang meet here, it is called the Gate of the Mysterious Female; because of its wondrous and unfathomable nature, it is called the Primal Pass. In fact, both refer to the same aperture” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 188). Thus, the “Primal Pass (

yuan guan 元關)” and “Gate of the Mysterious Female (

yuan pin 元牝)” are essentially one and the same: the former emphasizes the mysterious aspect of the Golden Elixir, while the latter highlights its dual nature of

yin and yang. This distinction is also reflected in Liu Yiming’s Figures. “Valley Spirit” is another important concept that has long been used in alchemical texts to describe the Golden Elixir.

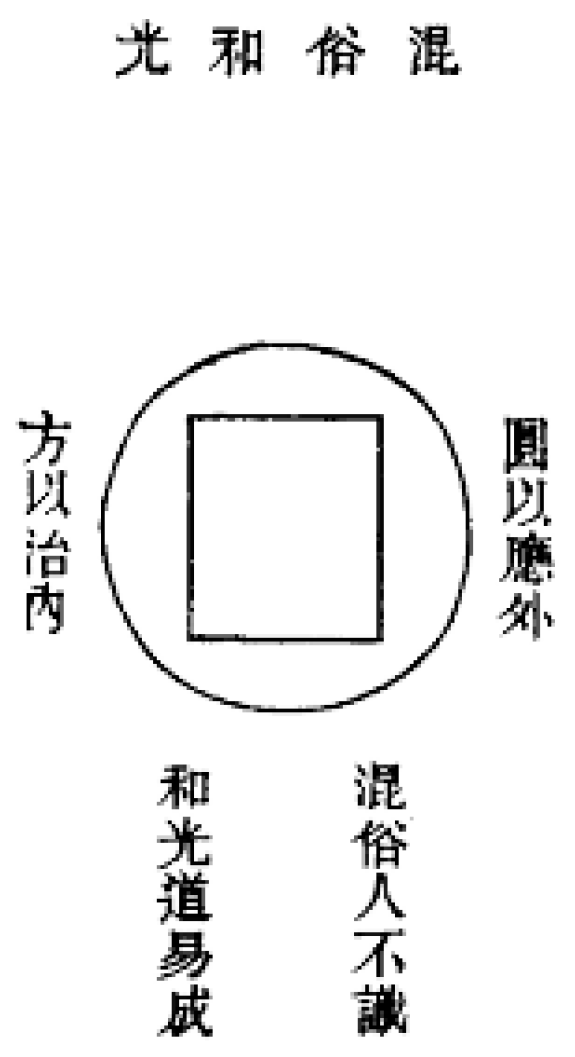

Liu Yiming used Figures to present some further details of the

Neidan cultivation process. For example, he believed that during

Neidan practice, one must undergo the stage of “blending with the mundane and merging with the radiance” (

hunsu heguang 混俗合光) (

Figure 27), a concept that also originates from the

Daodejing, specifically from the phrase “harmonize one’s light, be at one with the dust.” On this, Liu Yiming explained:

To blend with the mundane and harmonize with the radiance is to be outwardly round and responsive to things, yet inwardly square and self-possessed; to cultivate the Dao while adapting to worldly affairs; to remain unimpeded and unhindered whether one is obvious or obscure, going with or against the flow, and to practice the Dao in the utmost easy manner.

Evidently, he combined Laozi’s teaching of “harmonizing light and mingling with dust” with the

Book of Changes’ saying: “The virtue of the yarrow stalks is round and spiritual; the virtue of the hexagrams is square and wise” (

Zhu 2009, p. 239). In his Figures, this is represented as “square within, round without”—meaning “squareness governs the interior, roundness responds to the exterior.” This demonstrates that the Daoist alchemical path is not only a way of attaining immortality, but also a way of engaging with the world; alchemical cultivation is not separate from mundane affairs, and the true and the mundane are not strictly divided.

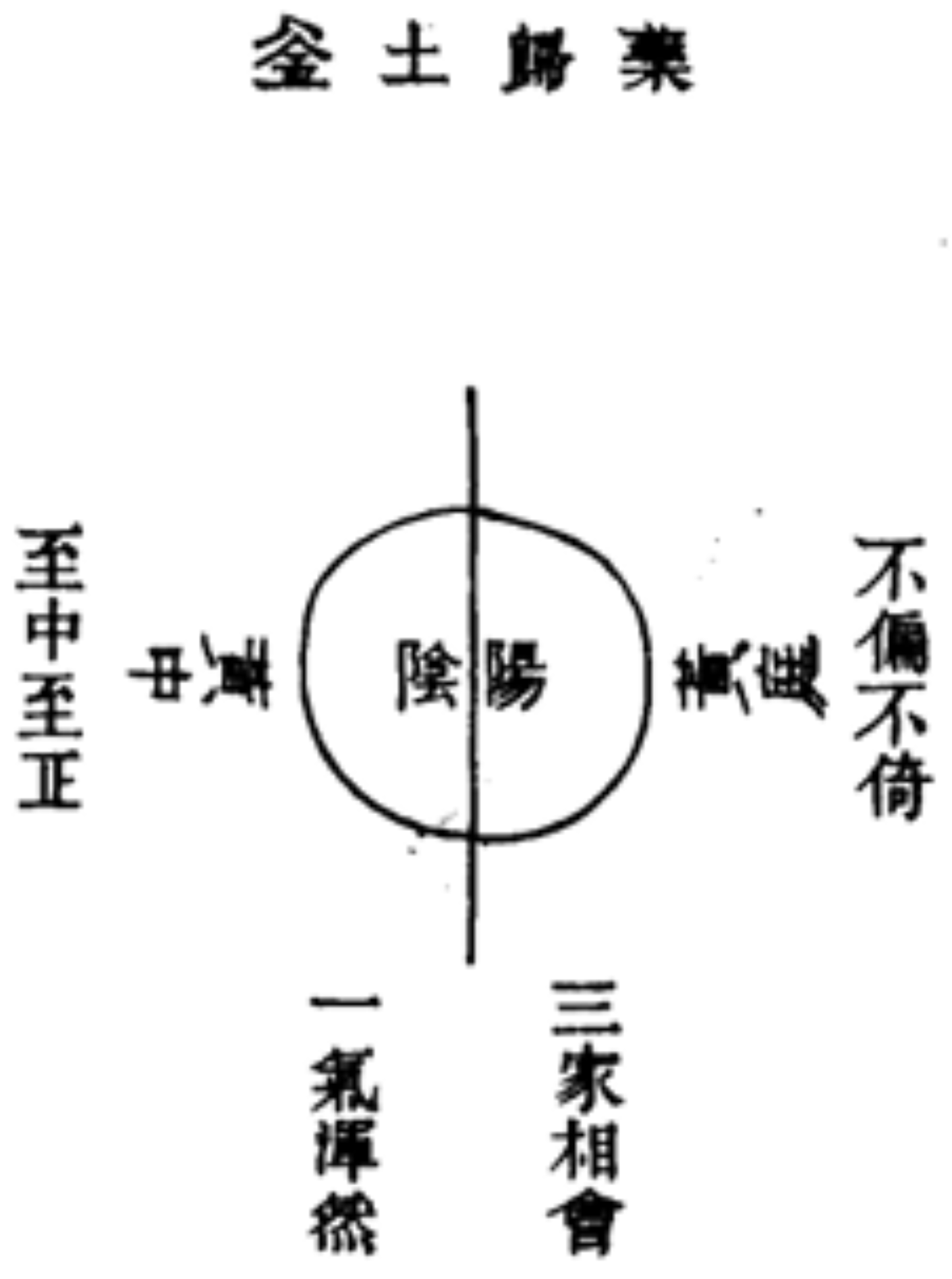

In addition, the medicine returning to the earthen cauldron (

yaogui tufu 藥歸土釜) (

Figure 28) is also an important step in the alchemical process. As he said, “Earth (

tu 土) is gentle in nature and able to nurture things; the cauldron governs cooking and refining, and is able to produce things. The cauldron is named for earth because it is the vessel for nurturing and completing things” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 199). It can be seen that the Golden Elixir possesses the power to nurture all things; thus, refining the Golden Elixir is not only about forming the Sacred Embryo and attaining the Dao, but also about nourishing all things and harmonizing

yin,

yang, and the five elements. Furthermore, the notion of cultivation not being separate from the mundane world is a common spirit of the Three Teachings. Liu Yiming used this to emphasize the value of the alchemical path.

Finally, there is a description of the stage after the Golden Elixir has been successfully refined. First is the congealing of the Sacred Embryo (

ningjie shengtai 凝結聖胎) (

Figure 29), that is, “the Sacred Embryo (

sheng tai 聖胎) refers to the embryo of the sage—namely, a state of no cognition or knowledge, the original face of the infant” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 200). It is “formless and without substance; although it is named ‘embryo,’ in reality there is no actual embryo to be seen. What is called ‘embryo’ is merely a metaphor for the true spirit being condensed and not dispersed (真靈凝結不散)” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 200).

The so-called Sacred Embryo is the state after the Golden Elixir has congealed. Although it is called an embryo, in reality, it is formless and immaterial, not a physical entity; what has been condensed is precisely the true

qi of the human body. Reaching this stage is akin to returning to the original state of an infant, from where one can proceed further to the completion of the embryo in ten months (

shiyue chengtai 十月成胎) (

Figure 30) Liu Yiming says:

When the embryo is fully formed in ten months, it is a sign that spirit is complete, qi is abundant, the root of mundane attachments is pulled out, external qi is assimilated, and yin is exhausted while yang becomes pure. This is just like a woman carrying a child, which only becomes fully formed after ten months. The Daoist alchemical practice uses the metaphor of the embryo becoming round in ten months to illustrate that after the Sacred Embryo has been congealed, one must be cautious and nurture it with care, bathing and warming it, ensuring that it completes perfectly and without flaw. The ten months is not a fixed period, but a metaphor drawn from pregnancy.

Thus, the so-called “ten months” is not a definite number but simply a metaphor; it indicates that in the process of refining the Golden Elixir, one must never slacken in diligence—even after the elixir is formed, it must be constantly nurtured to guarantee its complete and perfect fulfillment.

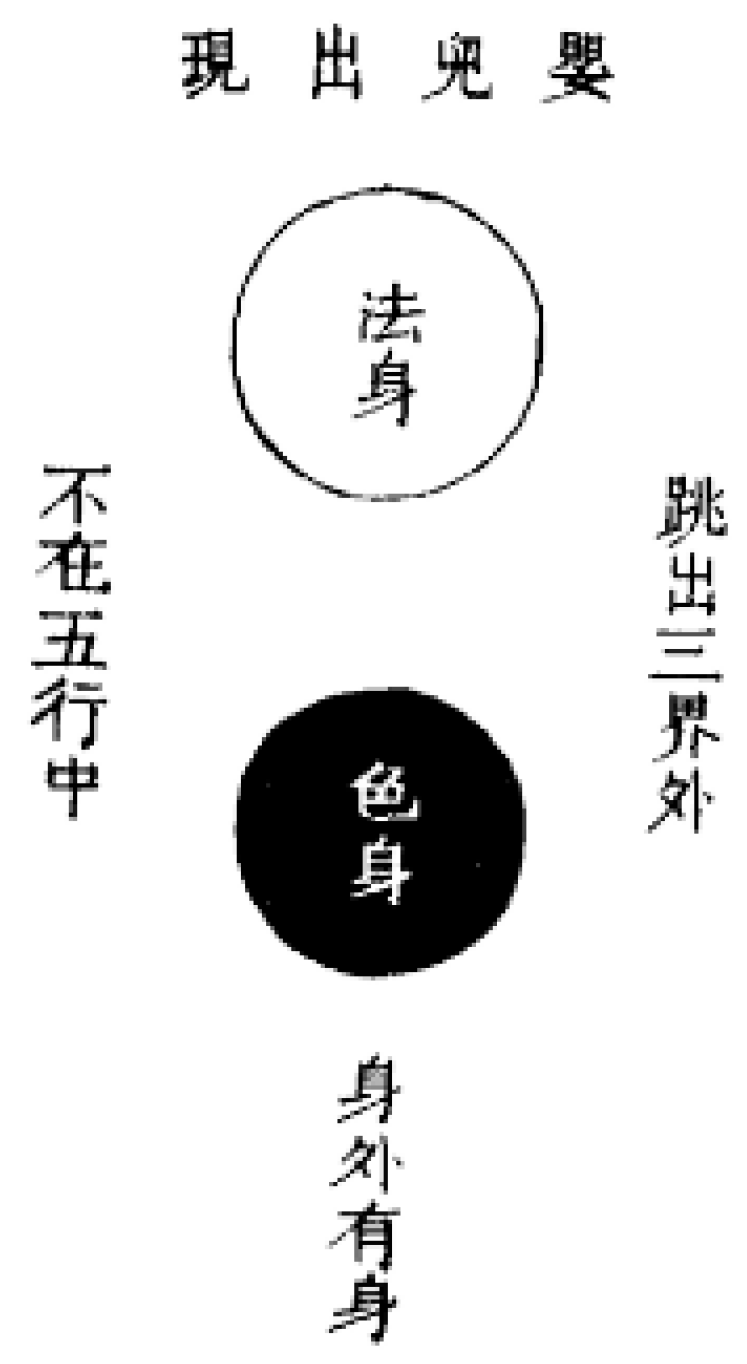

The fact that the Golden Elixir must still be nurtured and refined even after it has congealed indicates that the cultivation process never ends easily. In other words, as long as the physical body (

fa shen 法身) exists, self-cultivation is an unending pursuit, hence why Liu Yiming created the image of the appearance of the infant (

yinger chuxian 嬰兒出現) (

Figure 31) Regarding this, he says: “The Sacred Embryo is another Dharma body (

se shen 色身) held within the physical body; in transcendence and transformation, another Dharma body is born from within the physical body” (

Y. Liu 1990, p. 201).

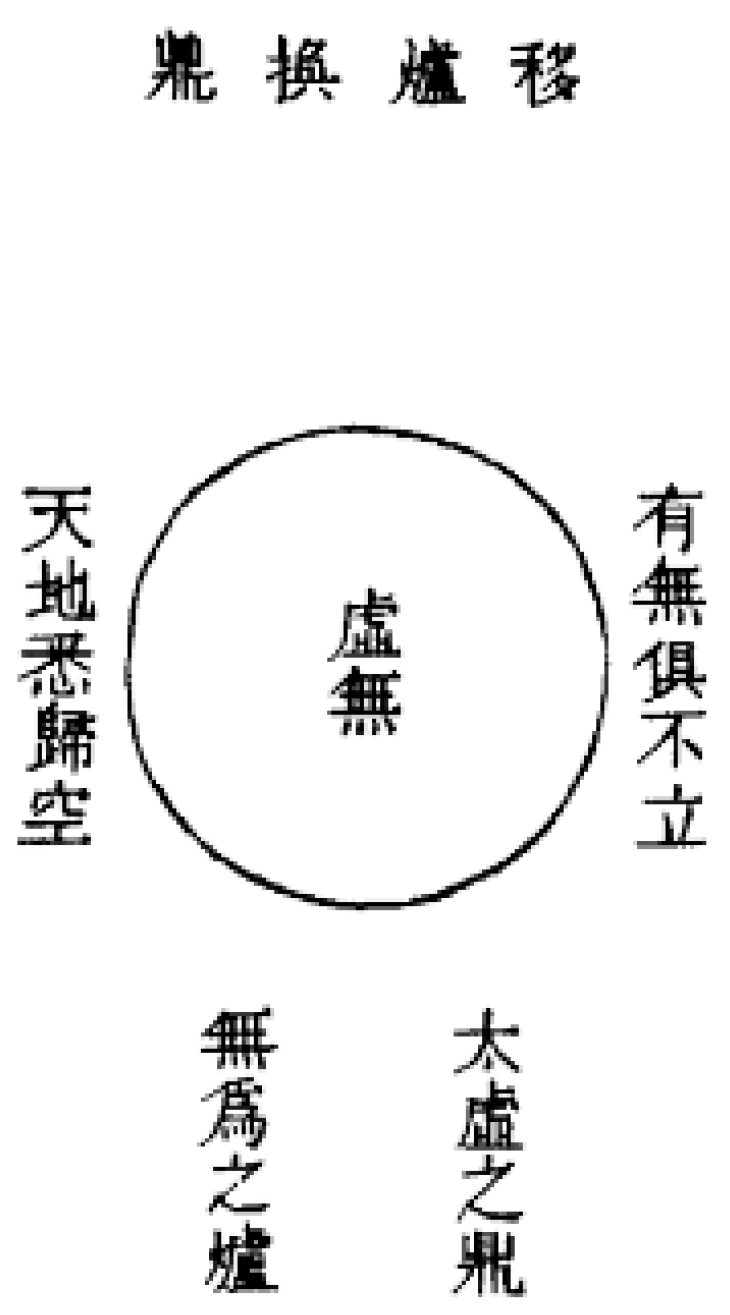

This illustrates that the physical body and the Dharma body are not simply a one-way transformation but are in constant transformation and circulation with each other. This is clearly influenced by Buddhist ideas of reincarnation, suggesting that the purpose of alchemical practice is not merely to attain immortality in this life, but to transcend the Three Realms and escape the cycle of the five elements, thereby leaving samsara and attaining true liberation. However, even upon reaching this state, cultivation is still not finished, so it is necessary to metaphorically shift the furnace and change the cauldron (

yilu huanding 移爐換鼎) (

Figure 32) As Liu Yiming says:

When the Great Dao is fully realized, there is a body outside the body, form and spirit are both wondrous, and one has already reached the state of a great sage. At this point, the furnace and cauldron are no longer needed, so why speak of shifting and changing them? The reason for shifting and changing the furnace and cauldron is to keep this Dharma body hidden and nurtured in secret, manifesting miraculous transformations and powers. What is the furnace to be shifted? What is the cauldron to be changed? The boundless void is now the cauldron, non-action is now the furnace, and all the former cauldrons and furnaces—such as the Qian cauldron, Kun furnace, cinnabar cauldron, crescent-moon furnace, and all the ingredients—are no longer needed.

Since the Great Dao has been fully realized, why is there still a need to shift the furnace and change the cauldron? This is because those still within the cycle of rebirth must continue to cultivate, and those who have attained immortality no longer use Qian or Kun as the cauldron and furnace for refining the ingredients. Instead, they use the boundless void as the cauldron and non-action as the furnace, continuing to refine the Dharma body.

(xing-ming 性命); in the Post-Heaven state, the center splits into nature and life

(xing-ming 性命); in the Post-Heaven state, the center splits into nature and life  (xing zhong ming 性中命). In truth, when the Post-Heaven state returns to the Pre-Heaven state, nature and life are re-united, and both ultimately return to the one center” (Y. Liu 1990, p. 32).

(xing zhong ming 性中命). In truth, when the Post-Heaven state returns to the Pre-Heaven state, nature and life are re-united, and both ultimately return to the one center” (Y. Liu 1990, p. 32).