Abstract

The article analyzes the responsory O vis eternitatis, the symbolic opening of Hildegard von Bingen’s primary music collection, to show how Hildegard’s musical choices support the key words and concepts of the composition. It examines usual components of construction, such as mode, melisma, range, and repetition, and shows that the piece is suffused with repetition in a manner not previously detailed. The article also explores a feature usually overlooked in writings on Hildegard’s music: the employment of ornamental neumes to highlight text, identifying instances of unusual frequency or rare use of specific neumes. The article then compares three significantly different recordings of O vis eternitatis, concluding that modern difficulties in the performance of ornamental neumes mean that our renditions today can never fully realize Hildegard’s conceptions. Stripped of their ornaments, Hildegard’s compositions resemble statuary from antiquity that has lost its original paint over the centuries—no longer as the creator intended, but still beautiful and deeply pleasing.

1. Introduction

St. Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) is unusual among composers for numerous reasons, beginning with the fact that her primary significance during her lifetime and for centuries thereafter was as a visionary theologian.1 The other activities for which she was known—her scientific works, her correspondence, her invented language and alphabet, her musical compositions—were considered ancillary to her sacred thought. Only in the last few decades have her compositions assumed a significant position in the world of sacred music. For many, she is now known more as a composer than as a religious figure.

As a composer, Hildegard is also unusual as a medieval figure. Most plainchant is anonymous, but Hildegard is a named composer and was, in fact, the most prolific of named chant composers. She has seventy-seven individual monophonic sacred songs (often referred to as the Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum, the Symphony of the Harmony of Celestial Revelations) and a music drama (Ordo virtutum) to her credit. Also uncommon is that she wrote all but one of her own texts.2 The following essay uses one of her compositions, O vis eternitatis, to show the ways in which the music supports her text. It includes a discussion of a crucial aspect of the notated work that is normally overlooked in examination of her music: the ornamental neumes. It also looks at three very different performances of the composition before concluding that our knowledge of the music as Hildegard conceived it will forever be incomplete.

2. O vis eternitatis

2.1. Text

The text and translation of O vis eternitatis are given below.3 Following a favorite practice of Hildegard’s, it opens with the dramatic syllable “O,” and that same syllable returns to begin the verse. Hildegard is also fond of superlatives, and we find one here at “maximo,” greatest. Although the text uses somewhat fewer sensory images than one finds at times in Hildegard’s lyrics, we still encounter one in the poetic “which divinity exhaled without the chain of sin.” And the text is completely typical in its use of evocative circumlocutions and metaphors throughout. Hildegard’s nuns would have recognized immediately that this is a text about God the Father and Son. God the Father is the “power of eternity,” a locution that is virtually unique in Latin writing.4 Christ is both the word and the Savior. Barbara Newman points out that “that form which was drawn from Adam” refers to Eve, and “by extension…all womankind and hence…. Mary” (Newman 1998, p. 268)—thus, Christ is incarnated through the Virgin. Newman notes that “his garments” represents the body, and that reference is switched in the course of the song from Adam to Christ; she also points out special aspects of Hildegard’s thought that are demonstrated in this text: that “Hildegard celebrates the Incarnation itself, not Christ’s death, as the central liberating moment in history” and that it is suffering rather than sin from which the world is saved.5

| O vis eternitatis, | Oh power of eternity, |

| que omnia ordinasti in corde tuo, | who ordered all things in your heart, |

| per verbum tuum omnia creata sunt | by your word all things were created |

| sicut voluisti, | as you wished, |

| et ipsum verbum tuum | and your word itself |

| induit carnem | assumed flesh |

| in formatione illa | in that form |

| que educta est de Adam. | which was drawn from Adam. |

| Et sic indumenta ipsius, | And thus his garments, |

| a maximo dolore, | by the greatest pain, |

| abstersa sunt. | were cleansed. |

| VERSE | |

| O quam magna est benignitas Salvatoris | O how great is the bounty of the savior |

| qui omnia liberavit | who liberated all |

| per incarnationem suam, | through his incarnation, |

| quam divinitas exspiravit | which divinity exhaled |

| sine vinculo peccati. | without the chain of sin. |

| REPETENDUM | |

| Et sic indumenta ipsius, | And thus his garments, |

| a maximo dolore, | by the greatest pain, |

| abstersa sunt. | were cleansed. |

| DOXOLOGY | |

| Gloria Patri et Filio | Glory be to the Father and to the Son |

| et Spiritui Sancto. | and to the Holy Spirit. |

| REPENTENDUM | |

| Et sic indumenta ipsius, | And thus his garments, |

| a maximo dolore, | by the greatest pain, |

| abstersa sunt. | were cleansed. |

| Hildegard von Bingen | Translation by Honey Meconi |

2.2. Musical Source

The music of O vis eternitatis exists in a single manuscript, the so-called Riesencodex (Wiesbaden, Hessische Landesbibliothek, Hs 2). This massive volume, most of it completed before Hildegard’s death in 1179, served as a quasi-collected works compilation of both her prose and her music. The music forms the final section of the volume and it includes all but two of her compositions (missing, for no clear reason, are the antiphons Laus trinitati and O frondens virga). The music section is not organized by the liturgical calendar, the norm for books of plainchant, but rather by hierarchy of subject matter—God, Mary, Angels, etc. More precisely, the Riesencodex music unit follows a double hierarchy, with (for the most part) shorter genres (antiphon, responsory) in the first section and longer ones (e.g., hymn, sequence) in the second, with Ordo virtutum closing the collection.6

O vis eternitatis opens the music section of Riesencodex, and it was unlikely to have been an arbitrary choice by the scribes. Of the nine songs in this initial “God” section of the manuscript, O vis eternitatis is the only responsory; all the other works are antiphons. O vis eternitatis is by far the longest of the group, and its text is different in a significant way. Four of the songs are prayers (O magne pater, O eterne deus, O pastor animarum, and O cruor sanguinis) and four others are songs of praise (O virtus sapientie for the Trinity, O quam mirabilis for the Creator, Spiritus sanctus for the Holy Spirit, and Karitas habundat for Divine Love). In contrast, O vis eternitatis tackles the incarnation at the heart of both Christianity and Hildegard’s theology. As Newman puts it, in O vis eternitatis we find the “fulfillment of God’s eternal design through creation by the Word and recreation by the Word-made-flesh.” (Newman 1998, p. 267). It is a fitting introduction to the sweep of sacred song that will follow.

2.3. Genre and Liturgical Position

Although the genre of O vis eternitatis is never explicitly indicated in the Riesencodex (many other pieces are marked appropriately, e.g., A for antiphon), the work as it appears in the manuscript is readily identified as a responsory. The piece opens with the response proper; the beginning of the verse is indicated by a marginal “v” and a large capital letter for the first word; the latter two repetenda are each copied with capital letters at the start and a short musical incipit; and the doxology begins with a very large “G”.

These components all mark the work as a “Great Responsory,” a genre distinguished by its length and complexity from the many responds otherwise sprinkled throughout the liturgy. While great responsories could appear during the offices of Lauds and Vespers, and could be used as well in processions, they were most frequently sung during the monastic office of Matins. Here they appeared as part of the “nocturns” that constituted the bulk of this lengthy office, where they were sung after each of the many lessons from Scripture. Not all great responsories included a doxology (typically just the first half of the lesser doxology); the ones that did were sung after the last in a group of three scriptural readings.

Many (though not all) scholars understand Hildegard’s sacred songs as forming part of the Opus Dei that is the foundation of monastic life; surely Hildegard was writing music for her nuns.7 In contrast to some of Hildegard’s compositions, however, the subject of O vis eternitatis is so generalized that we can attach it to no specific feast. Instead, the work could easily function as a kind of multi-purpose responsory providing a reminder of the central mystery of Christianity.

Although O vis eternitatis is presented in the Riesencodex as a responsory, it was not necessarily intended originally—or perhaps exclusively—as such. The text alone, without musical notation, appears in several manuscripts within a group of Hildegard’s writings that includes both prose texts and the (unnotated) texts of a number of Hildegard’s songs.8 The purpose of these collected texts is unknown, but scribes considered them sufficiently significant to copy them multiple times; O vis eternitatis appears thus five separate times.9 As Newman has pointed out, what is striking about all of these song texts is that they are always stripped of identifying liturgical components--no genre or subject indications, no performance cues (Newman 2007, p. 349). In the case of O vis eternitatis, the text of the response and verse appears (with nothing marking the commencement of the verse), but no doxology or repetenda are given. This is true for each of the manuscripts transmitting the text.10 Thus, the text at least had some existence outside of the liturgical round, even if the musical version functioned within it.

2.4. Analytical Elements: The Usual Suspects

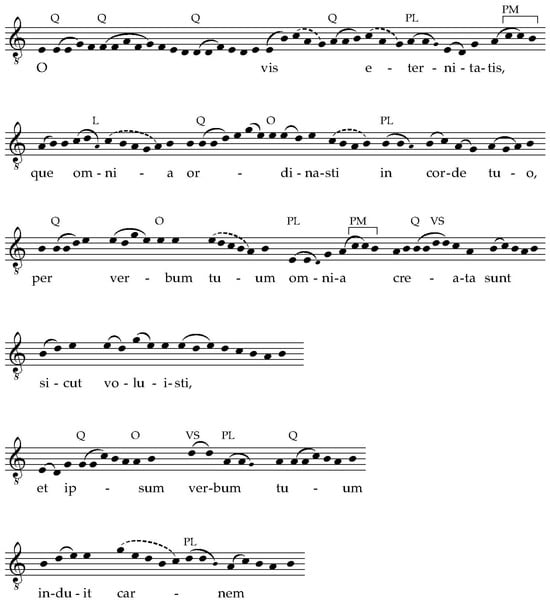

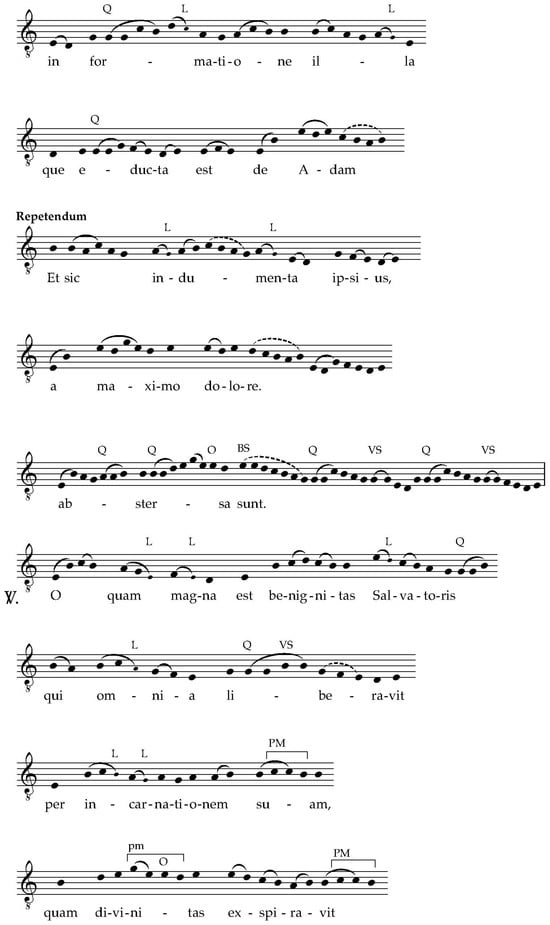

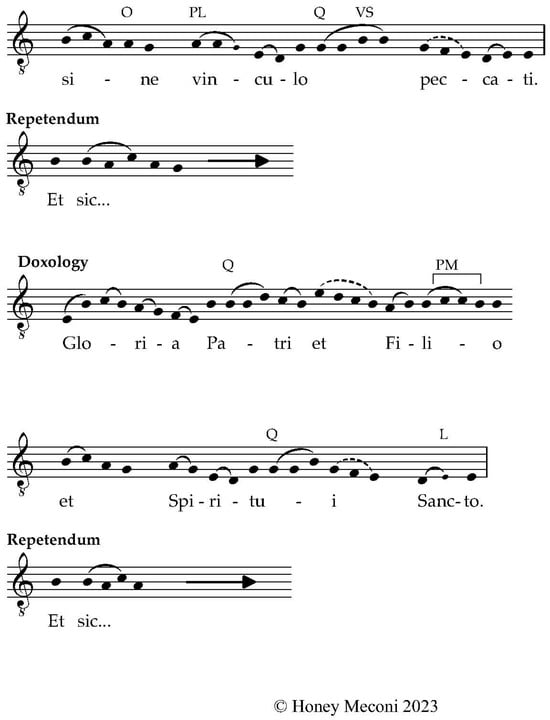

Hildegard’s composition, originally written in neumatic notation, is transcribed here in stemless noteheads; see Figure 1.11 A slur indicates that the notes form part of a single connected neume, e.g., pes or clivis. A dotted slur is used for neumes whose components are not connected, e.g., climacus. A bracket is used for a neume with both connected and unconnected components (e.g., pressus maior) or when an ornamental neume is combined with another neume. Small noteheads indicate liquescence. The many letters above the staff identify ornamental neumes; they will be discussed later.

Figure 1.

Hildegard von Bingen, O vis eternitatis.

2.4.1. Mode

O vis eternitatis is written in E mode, Hildegard’s most frequently used mode. The disposition of the pitches is quite close to the standard Phrygian, with D as the lowest pitch and gg as the highest (the usual highest pitch for Phrygian would be e).12 Marianne Richert Pfau carefully outlines the ways in which Hildegard employs mode to structure the composition (Pfau 1990, pp. 63–65; Pfau and Morent 2005, pp. 147–49). In the opening of the work, the initial melisma clearly establishes E as the modal center of the work, but then embarks on an extended avoidance of E as a cadential pitch. We find instead that every one of the phrases before we get to “Et sic indumenta” ends a fifth above the final, on b, keeping the listener and performer in a constant state of anticipation. In the few instances where the melody touches down on E (eterNItatis, OMnia, et, in), it is approached by leap (rather than the normal stepwise motion for a cadence) and moves instantly to D. Only as we near the end of this initial section does E begin to occur more frequently, moving restlessly from the end of “illa” through “que educta est” before the melody leaps upwards again to pause again on yet another b.

It is only with the “Et sic indumenta” section, where Hildegard states the goal of the text (and thus his garments, by the greatest pain, were cleansed), that we reach our firm modal goal as well. Each of the three phrases of the repetendum closes with a clear cadence on E, and two of the phrases begin on that pitch as well. Of course, this section will return twice more as well, emphasizing the finality of both text and music. As we expect, both verse and doxology provide more closure than the opening solo portion, since they are complete thoughts. Yet the opening section is a complete thought as well: “which was drawn from Adam” can end a sentence. But Hildegard wants us to keep moving forward and thus gives us only a half cadence on “Adam”.

As she often does, in O vis eternitatis Hildegard uses leaps between E and b or the reverse to emphasize the mode. We see this in the opening phrase at the start of “vis” (power); between “tuum” and “omnium” in the third line; between “voluisti” and “et;” between “carnem” and “in;” within the “dolore” melisma; at the beginning of “abstersa;” at the opening of the verse and between “est” and “benignitas;” between “per" and “incarnationem;” between the end of the verse and the first repetendum; at the start of the Doxology and between “Gloria” and “Patri.” We also find the upward leap from b to e between “Patri” and “et” in the doxology and between “benignitas” and “Salvatoris” in the verse. The modal foundation is highlighted most forcefully in the employment of the E/b/e outline at the start of “a maximo” and at “de Adam.” Hildegard is not alone among composers of the time in making use of leaps of fifths and fourths to outline modal identity, but her choices are nonetheless effective. Pfau elegantly summarizes the result of this modal emphasis on the text:

“The assignment of musical phrases to the text units, the consistent arrangement of the phrase endings, which are always connected to the fifth or the final, as well as the arrangement of the tonal space in the stable fifth (E-b) or fourth (b-e), within which the phrases unfold, seem to symbolically reflect the basic idea of the text, which explores the organizing force in the heart of eternity on a musical level. Everything in the song appears deliberate and full of dignity: the gradual opening of the tonal space, the regular neumatic setting of the text with three or four notes per syllable, the phrase goal pitches on b or E… The song resembles a musical meditation on the incomprehensibility of the mystery of the incarnation and its tone captures the dignified veneration that speaks from Hildegard’s deeply felt poetry.”13

2.4.2. Melisma

In addition to the modal layout, melismas play a key role in articulating text. Hildegard employs a variety of text underlay in O vis eternitatis: sometimes syllabic, usually neumatic, and occasionally melismatic. Melismatic passages stand out, and Hildegard usually reserves her melismas for words of some significance. Short melismas in O vis eternitatis appear on ORdinasti (ordered), voluiSTI (wished), IPsum (itself), CARnem (flesh), FORmatione (form), and ILla (that); ipsum, carnem, and formatione are of obvious significance in a text concerned with Christ’s embodiment.

Hildegard saves her most significant use of melisma, however, for the music that opens and closes the composition. As happens quite often in Hildegard’s works, O vis eternitatis begins with a dramatic “O” in a melismatic setting of nineteen pitches. This is immediately followed by a short melisma on “vis” (power), a reference to God the Father. The importance of the divine subject is thus emphasized right from the start; we remember, too, that “vis” begins with an upward leap of a fifth. Hildegard also opens the verse with another “O,” but this time the word receives only four pitches. That word, however, has been preceded by the melismatic closing of the repetendum, which will ultimately return to conclude the entire work. Here, Hildegard first gives a short melisma on inDUmenta (garments) close to the beginning of the repetendum, but she saves her big guns for the end. The powerful word “dolore” (pain) receives a twelve-note melisma on its final syllable, followed immediately by the flowing “abstersa sunt” (were cleansed), with a seven-note melisma on the first syllable, an eight-note melisma on the second, and an impressive thirty-note melisma on the final word.

2.4.3. Extremes of Range

Another technique Hildegard can use to highlight text is the placement of the highest and lowest pitches. The range of the work is an eleventh—large by the standards of traditional Gregorian chant, but not unusual for later chant, and for Hildegard’s works, actually on the narrower side. In O vis eternitatis, the low pitch, D, is present almost from the start, occurs frequently, and is used throughout, last appearing as the penultimate pitch in the entire work. With E as the final, the ready presence of the note frequently used to lead to a cadence is unsurprising.

In contrast, the high pitch, g, is used more sparingly, but by Hildegard’s standards (where the highest pitch often appears only once or twice within a work, and is sometimes reserved until close to the end), it has a rather prominent role, appearing in the opening portion, the repetendum, and the verse. It is used in the following words: ordinasti (ordered), verbum (word), voluisti (wished), carnem (flesh), maximo (greatest), abstersa (cleansed), and divinitas (divinity). Four of these words (ordinasti, voluisti, carnem, abstersa) have already been noted for their use of melisma, and each of the remaining three is an obvious choice for emphasis. The “word” is Christ; divinity is self-explanatory, and “maximo” is also a punning reference to the “most” that the high pitch represents.

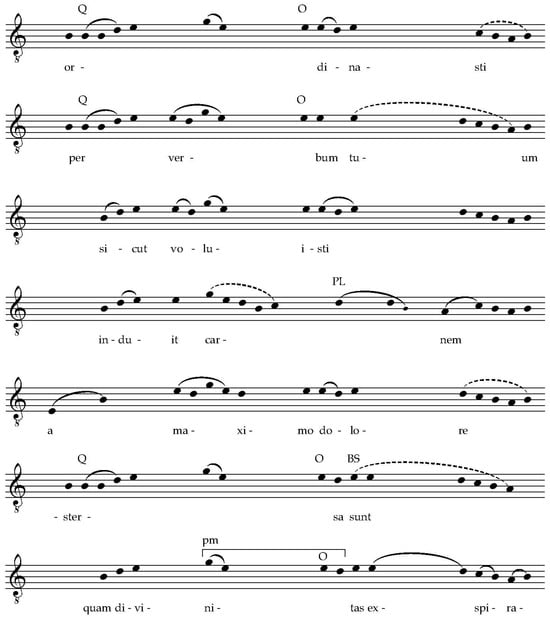

2.4.4. Recurring Melodic Unit

It is not merely the highest pitch that all of these words share, however; it is also the contour of the phrase in which they appear. Each of these words is part of a general melodic unit that begins on b, moves up to g (usually via d/e or e/d or both), goes down to e/e/d, and then follows a mostly stepwise descent to a/b. See Figure 2. Units following this basic design appear at ordinasti (ordered), per verbum tuum (by your word), sicut voluisti (as you wished), induit carnem (assumed flesh), a maximo dolore (by the greatest pain), (ab)stersa sunt (were cleansed; this ending differs from the template), and quam divinitas exspira(vit) (which divinity exhaled)—all vital aspects of Hildegard’s text.

Figure 2.

Recurring Melodic Unit in Hildegard von Bingen, O vis eternitatis.

In every instance, the high g is both approached and left by leap rather than step, meaning that the pitch f never occurs in O vis eternitatis. Avoidance of an individual pitch sometimes occurs in Hildegard’s music; here, the absence of f eliminates any chance of implying cadential motion on e rather than on the expected E an octave lower. A leap to a high pitch also places greater emphasis on that pitch, again contributing to the importance of the word in question.

The melodic unit is first found in the second line of text and returns three more times in fairly quick succession, then appears twice more in the repetendum component of the work, and returns in the verse. Only the Doxology is without an appearance, and the triple appearance of the repetendum means that the melodic unit appears as a quasi-idée fixe throughout the work.

2.4.5. Other Musical Repetition

The melodic context for the highest pitch is not the only repeated material in O vis eternitatis. As is typical for Hildegard, small-scale repetition occurs as well; look, for example, at the opening words “vis eternitatis.” After the initial E, notice that the pitches b/c/a/G/a/a (on vis) are immediately repeated at the end of “vis” and the beginning of “eternitatis,” thus musically uniting the adjective and the noun.

Hildegard also uses large-scale repetition in addition to the obvious repetitive structure of the responsory. One of the striking aspects of Hildegard’s responsories is that she writes her own music for the verse and doxology; in contrast, the norm in chant composition is to use existing melodic formulas of limited musical interest for these two sections. In addition to avoiding the standard pre-existent formulas, Hildegard also typically unifies the verse and doxology musically in some way. In the case of O vis eternitatis, we see that the two phrases of the doxology are condensed forms of the first and last lines of the verse. The connection is subtly heightened by the fact that the doxology phrase “et Filio” (and the son, Christ) is a variant of the verse word “Salvatoris” (savior, Christ).

The verse itself is filled with repeated material. The opening of the first line reappears in a varied form as the opening of the third line. The music of the second line, beginning with the word “omnia,” is expanded into the music of the fifth line (“who liberated all” thus becomes “without the chain of sin”). The third line, as noted, begins with material derived from the first line and ends almost exactly as the fourth line does. The fourth line has already been shown to be a form of the large high-g unit appearing multiple times in O vis eternitatis, and we now see that it closes almost exactly as line 3 does; everything in line four is thus found elsewhere.

The response itself involves considerable repeated material. Note how “per verbum tuum omnia creata sunt” (by your word all things were created) is essentially the same as “sicut voluisti, et ipsum verbum tuum” (as you wished, and your word itself). The melodic line beginning with “omnia creata” is itself derived from the earlier “-nitatis, que omnia.” If we were to label that latter motive “A,” and the motive with the high g “B,” we would have a road map of A/B/free/B/A/B/A/B that covers a good portion of the response, with various small-scale reminiscences elsewhere. O vis eternitatis is suffused with melodic and hence textual interconnections.

2.5. Analytical Elements: Ornamental Neumes

A crucial component of Hildegard’s music that is almost never discussed in terms of its significance is her reliance on ornamental neumes (sometimes called special neumes). Hildegard is known to use more of these than her contemporaries, and the edition provided here, unlike most editions, shows just how frequently these appear in O vis eternitatis. The letters above the staff indicate which neumes are ornamental; the abbreviations are as follows:

| BS | bistrophe |

| L | liquescence |

| O | oriscus |

| PL | pressus liquescens |

| PM | pressus maior |

| pm | pressus minor |

| Q | quilisma |

| VS | virga strata |

Everything listed above is a specific neume with the exception of liquescence. This is a special performance indication found in several different neumes, including (in O vis eternitatis) the pinnosa, the cephalicus, the ancus, and the epiphonus. It is only the liquescent component of those neumes that is out of the ordinary, making it unnecessary to specify precisely which neume is involved.

The modern listener might be forgiven for being unaware of the frequent presence of these neumes in Hildegard’s music. Most of them are not indicated in modern editions of Hildegard’s music, and almost all of them are accordingly ignored in today’s performances. There is a reason behind this, however, which is that we have little idea of how they should be executed.14 Here is how they are identified in their respective articles in Oxford Music Online:

Oriscus: “a special neume signifying one note. It is usually found added to another neume as an auxiliary note…. It is not clear how the oriscus should be performed.”(Oriscus (n.d.))

Virga strata: “there is doubt as to its exact significance….The alternative name gutturalis… probably indicates that this neume involves a note whose ambiguity of pitch springs from a peculiarity of the manner of its performance.”(Virga Strata (n.d.))

Pressus: “a special neume… the exact significance is unclear.”

Bistrophe: bistrophes and tristrophes “were distinguished from simple repeated virgae or puncta… probably by the manner of their performance, although it is not certain what this may have entailed.”(Hiley (n.d.a))

Liquescence: “Liquescence arises in singing diphthongs and certain consonants to provide for a semi-vocalization of that vowel or consonant as a passing note to the next pitch.”(Liquescent (n.d.))

Quilisma: “a special neume… Aurelian of Réôme… spoke of it as a trembling and rising sound… and most modern writers have not ventured beyond this.”(Hiley (n.d.c))

Even if most of these ornamental neumes are neither indicated in modern editions nor attempted by performers, they are nonetheless there. Examining them, even without any certainty concerning their precise rendition, draws our attention to Hildegard’s disposition of these special indications in O vis eternitatis. Some appear frequently (in this work and in her other compositions), while others are noteworthy for unusual aspects.

Liquescence and quilismas are used throughout. Many (though by no means all) instances of liquescence fall in places where a voiced consonant would be appropriate, or a diphthong exists, and liquescence is thus found fairly often in Hildegard’s works, including this one. The quilisma is likewise one of the most frequently occurring ornamental neumes in Hildegard’s output, and it is a rare work that does not use one or more of them; O vis eternitatis includes many examples. In contrast, the oriscus appears far less often in this composition, and the bistrophe is present just once (not including its returns in the repetenda). The virga strata appears three times on its own, and three times as part of a combined quilisma/virga strata neume. The quilisma/virga strata combination is found only thirty-one times in all of Hildegard’s output, so it is noteworthy that it is present three times in O vis eternitatis. Although the virga strata on its own appears with moderate frequency in Hildegard’s works, it is found only three times in a subpunctis format—and two of those three times appear in O vis eternitatis, at the end of the repetendum. The last virga strata is followed by three puncta—the only time in all of Hildegard’s music where that happens. As for the pressus maior, it is always part of a combined pes/pressus maior neume in O vis eternitatis, where the pressus maior component always marks the c/b half step (this is not a universal characteristic of the pressus minor in Hildegard’s music). The pes/pressus maior neume is the most common extension of the pes within Hildegard’s output, but it is nonetheless striking that it appears five times in O vis eternitatis—though never in the choral repetendum. The pressus liquescens, a common neume for Hildegard, is always on its own in this composition, and it is found on a variety of pitches. In contrast, the pressus minor appears only once in this composition; it is a rare neume for Hildegard and is found (in this specific combination of clivis/oriscus/punctum) only three times in all of her works.

In other words, while many of the ornamental neumes found in O vis eternitatis are quite common within Hildegard’s works, two appear here with unusual density (the quilisma/virga strata combination and the pes/pressus maior extension) and two others are presented in rare or even unique iterations (the pressus minor and the self-standing virga strata in subpunctis format).

We can make several observations about the deployments of these neumes. The word “verbum” appears twice in O vis eternitatis; we have already noted that one of those appearances includes the highest note of the work. But the other is marked as well: it uses two neumes, one for each syllable, and each neume is ornamental: a virga strata for “ver-” and a pressus liquescens for “-bum.” Thus, Hildegard singles out this word in some manner for each appearance.

Similar differences appear in the units surrounding the high g. As already seen, all are slightly different in their precise choice of pitches, but they also differ in their use of special neumes. “Sicut voluisti” and “maximo dolore” use no ornamental neumes at all, and “induit carnem” has only a single liquescent neume. The four others each highlight the initial descent from high g with an e oriscus following the first e, and three of these begin the ascent to the high pitch with a quilisma prepunctis. The “abstersa sunt” unit uses the only bistrophe in the piece. Far more striking, though, is the “quam divinitas” found in the verse. The syllabic beginning leads up to a pressus minor that begins on the high g. The pressus minor is a neume that appears only a dozen times in Hildegard’s music, and, as noted, only three times in this specific format of clivis, oriscus, punctum.

We have already pointed out that the opening of O vis eternitatis mirrors the closing in its emphasis on melismatic writing. The same is true when it comes to special neumes. The second note of the piece starts a quilisma on E (the modal center of the work) and almost immediately thereafter begins another quilisma on F; a third quilisma, on D (still on the opening “O”), follows shortly. “Vis” likewise is marked by a quilisma, and the last word of the opening phrase, “eternitatis,” uses a pressus liquescens on “ter” and closes the word with a pressus maior.

The last line of the piece, “abstersa sunt,” is equally ornate, if not more so, with four quilismas, an oriscus, a bistrophe (the only one to appear in this piece), and two virga stratas--the last five special neumes all on the final melismatic “sunt.” This elaborate conclusion is thrown into relief by the preceding two lines of the repetendum, which are marked merely by two modest liquescent pitches on “indumenta.” Remember, too, that a performance of the responsory will feature this final flourish three different times.

The preceding discussion shows how Hildegard uses various musical components to emphasize key concepts of her text. Tonal tension and release are balanced to focus attention on the modal confirmation in the words of the repetendum. Melismas highlight key words. The highest pitch, used in many of Hildegard’s works only once or twice towards the end of a composition, appears here instead on seven different occasions as part of a recurring but varied melodic unit that, again, centers on important aspects of the text. Additional melodic unity is created by the use of both small- and large-scale varied repetition, especially in the Verse and Doxology. Throughout the work, the use of ornamental neumes, some in common use but others of restricted circulation, again draws attention to key concepts. The overall repetitive structure of the responsory form itself means that the elaborate ending of the repetendum, which mirrors the opening phrase in certain aspects, recurs as a refrain that concludes the composition with a final flourish—a flourish that itself includes the reiterated melodic unit present almost from the beginning of the work. And throughout the work, important words and phrases receive emphasis via multiple means, drawing attention to themselves by combinations of factors (e.g., “abstersa sunt” by melisma, extremity of range, ornamentation; “divinitas” by ornamentation and extremity of range).

3. Performance Examples

In many respects, O vis eternitatis is an excellent work for comparing performances. Because the music is transmitted in a single source, there are no issues concerning variant readings between manuscripts. Since it is in a pure E mode, without any accidentals, it avoids the problems of music ficta that plague many of Hildegard’s works.16 As a responsory, its performance road map is straightforward, in contrast to Hildegard’s many psalm antiphons where we lack any indications as to what psalms would have accompanied them. And not least in significance is the fact that the reading in Riesencodex is a clean one; a surprising number of Hildegard’s works have errors scattered throughout. Thus, those choosing to perform O vis eternitatis begin without the problems that beset many of her compositions.

A look at what is freely available on YouTube provides some indication of the range of choices that performers of O vis eternitatis make. Examples include renditions by solo singers (e.g., Kristia Michael, Azam Ali), solo violin and strings (Mari Samuelsen in an arrangement by Tormod Tvete Vik, unexpectedly on the staid Deutsche Grammophon label), an ensemble where men and women sing the chant together (Ensemble für frühe Musik Augsburg), and various female choirs. Some of these performances are immensely inventive and often captivating; one gets the sense that Hildegard’s composition is viewed by these artists as a starting point for improvisation and flights of fancy along the lines of a jazz standard. Not all renditions provide every component of the work (response, verse, doxology, repetendum).

For purposes of comparison, we will look first at two relatively straightforward recordings by performers with superlative claims to intensive engagement with the music of Hildegard.17 One recording is by the professional early music ensemble Sequentia, who have recorded all of Hildegard’s music and whose first recording of Ordo virtutum was the earliest one ever made of that work (and one of the earliest of any records devoted to Hildegard). The second performance is by the nuns of Hildegard’s reconstituted abbey, who are among the most important figures in the long process of reclaiming Hildegard’s legacy, both musical and otherwise, and who provided the first complete printed edition (albeit in modern chant notation) of Hildegard’s compositional output.18 The interpretations of these two groups are different, but they were also generated by different impulses. As a professional ensemble, Sequentia performs in concert situations and makes recordings for commercial sales. O vis eternitatis is on their “Canticles of Ecstasy” CD, a miscellaneous collection of Hildegard’s works and other pieces.19 The nuns’ rendition, in contrast, appears within a reconstructed liturgical Vespers service, where it follows an intoned reading from the Book of Revelation.

Sequentia’s performance of O vis eternitatis:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Vcv2HdApcs&list=RD_Vcv2HdApcs&start_radio=1 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

Benedictine Nuns of the Abbey of St. Hildegard’s performance of O vis eternitatis:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2jaEeu2Yt1g&list=RD2jaEeu2Yt1g&start_radio=1 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

As noted, O vis eternitatis is a responsory, and performance of a responsory alternates between a soloist and the chorus. The usual procedure is that the soloist is entrusted to the opening of the work, the verse, and the doxology, while the chorus joins after the initial solo section and then sings the repetendum repeats as well. In contrast to some of Hildegard’s songs, where the highest and/or lowest notes are entrusted to the soloist, in O vis eternitatis both soloist and chorus explore the full melodic range of the work.

Both Sequentia and the Abbey nuns perform all sections of O vis eternitatis in the proper order, Sequentia an octave higher than written pitch, the nuns using C# as their final. Both choices are appropriate, since fixed pitch did not exist in the twelfth century. The versions differ somewhat in their solo/choral divisions. The nuns begin the work not with a solo incipit, as is the expectation, but rather with the full choir. The soloist enters only with the verse, and then returns for the doxology, with the chorus taking the repetenda.20 In contrast, Sequentia begins with a soloist. The chorus enters for “et ipsum verbum” and continues through “in formatione illa,” with the soloist returning for the single line “que educta est de Adam.” The chorus then sings the repetendum, the soloist is given the verse, and then the remainder of the work, including the doxology, is given to the chorus.21 Technically speaking, then, neither group follows the usual performing assignments for a responsory, although the nuns are lacking only in an initial solo incipit.

While both groups sometimes (but not always) provide a voiced consonant for liquescent pitches, they differ substantially in their treatment of quilismas. If the quilisma spans a third, Sequentia will fill in the pitch between the first and second written notes; if the quilisma outlines a fourth, Sequentia sings the lowest pitch, the next pitch, and then skips a third to the highest pitch. The nuns, on the other hand, sing only the two pitches that the quilisma outlines, and the lower pitch is sung as a single note rather than a double as suggested in the edition given here and in many (but not all) other editions.22 The two groups treat repeated notes differently as well, with the nuns articulating each note, and Sequentia joining repeated notes together with a single articulation.23

A major difference between the two is that the nuns sing without accompaniment, while an instrumental drone (organistrum and two vielles, instruments used in the Middle Ages though not necessarily in Hildegard’s abbey) provides the background for the Sequentia performance. And the treatment of rhythm and tempo is likewise significantly different. In general, the notes in the nuns’ rendition are given approximately equal value, though not rigidly so. Sequentia, on the other hand, performs the melodic line with great rhythmic freedom and flexibility; some notes rush by while others are caressed lingeringly. The result is that the nuns complete the piece in just over six minutes (6:08), while Sequentia’s recording lasts almost two minutes longer (7:57). Even at that pace, the Sequentia recording is still shorter than the one by the Oxford Camerata, which extends almost a minute beyond the Sequentia performance (8:55).

A third, quite different performance is the one by Kristia Michael, a Cypriot singer, composer, and “sound artist” who is director of the medieval-focused Sibil•la Ensemble. She is the sole vocalist in her recording of O vis eternitatis, where she is accompanied by an organ drone. While the recordings by the nuns and by Sequentia simply present their respective album covers on YouTube, Michael’s version is an evocative video. She performs in a dimly lit space with a stand light providing illumination of the score while vague video images are projected behind her. The goth-like atmosphere of the video is underscored by Michael’s black lipstick and severe attire, also black.

Kristia Michael’s performance of O vis eternitatis:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1SlL-hBeSA4&list=RD1SlL-hBeSA4&start_radio=1 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

Her rendition of the work, pitched on D, lasts barely five minutes. But while the other two recordings present the entire responsory with all repeated material, Michael gets through only the response itself—no verse, no doxology, no returning repetendum—in those five minutes. Her overall tempo in this severely truncated version is thus slower than either of the other groups, with much lingering on individual notes. The main difference, though, is not so much tempo as it is vocal production. The timbre is sometimes quite nasal, and Michael constantly adds little vocal roulades, shakes, and twirls that introduce a variety of notes and pitches not in the written music; her website remarks that “subtle are the guttural arabesques with which she adorns the music.” (Michael (n.d.)).

The discussion above about Hildegard’s extensive use of ornaments and our lack of knowledge as to how they were performed brings up the possibility that Michael’s own heavily ornamented performance might more closely resemble what Hildegard and her nuns actually sang than the two recordings first discussed.24 In fact, though, Michael’s various additions do not correspond at all to places where Hildegard has inserted an ornamental neume; vocal lines that are written in the manuscript as an unexceptional series of pitches void of any suggestion of special performance receive generous embellishment by Michael. Further, there is no consistency in Michael’s treatment of liquescence, quilismas, or any of the special neumes indicated by the scribes. Michael’s website indicates that she “focuses on the experiential and spiritual aspects of early and contemporary music;” O vis eternitatis is clearly another canvas for her evocative experimentation.25

These three recordings demonstrate some of the many possibilities of interpretation that today’s singers bring to Hildegard’s music. The person who did not know O vis eternitatis before listening to these versions would likely not immediately recognize that they were all the same composition. Yet the same reaction would be true for a very large number of performances of Hildegard’s music. The uncertainty surrounding medieval performance norms is simply too great for consistency across modern interpretations, even those sharing an identical goal (whether that is for concert performance or liturgical inclusion).

4. Conclusions

O vis eternitatis demonstrates how Hildegard uses various compositional techniques to emphasize important words and concepts in her text. These include judicious use of modal markers, melisma, extremes of range, and repetition on the small, medium, and large scale. Also significant for Hildegard, though almost always overlooked today, is her reliance on a variety of ornamental neumes for further textual emphasis.

Despite the fact that O vis eternitatis is an unproblematic piece in its manuscript presentation, modern performances differ dramatically. Perhaps their greatest commonality is their lack of engagement with any of Hildegard’s many ornamental neumes except for the quilisma and some liquescent neumes. Such neglect is understandable; we have almost no information on how these neumes would have been performed. And yet these neumes festoon O vis eternitatis, and Hildegard uses them, as with her other devices, to highlight important aspects of the text.

Given that our knowledge of these neumes is simply too limited ever to capture Hildegard’s original intentions, modern performances will of necessity be incomplete. Yet this should not stop us from continuing to engage with these exceptional works. The analogy to draw here is with Greek sculpture. We now know that, far from having unadorned marble as their intended medium, statues in classical antiquity were painted in order to make them as lifelike as possible. Yet most of them lost their paint over the centuries, and the plain white marble versions that survived inspired the great sculptors of the Renaissance and later periods. Their works—and those that survive without their paint from antiquity—have their own beauty.

Thus it is with Hildegard’s compositions. They have largely lost their “paint” in modern editions and performances—the many special neumes that provided a kind of flash and sparkle and that contributed to the outlining of key words and phrases in the text. But the bare bones remain—the beautiful lines, now largely unadorned, that continue to generate both intellectual and emotional responses. We can still celebrate Hildegard’s achievement, even if we can no longer truly duplicate it.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The literature on Hildegard’s visionary and theological writing is extensive; a concise summary of her thought can be found in Mews (1998). Her distinctive woman-centered theology is explored in Newman (1987); her unique concept of cosmology is treated in Fassler (2023). Each of those studies places her contributions in the context of earlier writers. |

| 2 | Hildegard set the Kyrie text once. |

| 3 | The translation, which follows the layout in Newman (2007), pp. 373–74, is freely available at (Meconi n.d.) Honey Meconi, ed., The Compositions of Hildegard von Bingen: Editions and Translations: www.honeymeconi.com/hildegard (accessed on 1 August 2025). A bibliography for O vis eternitatis can be found at the (Hildegard of Bingen Music Research Guide n.d.): https://dact-chant.ca/hildegard.html (accessed on 1 August 2025). |

| 4 | I am grateful to an anonymous reader for bringing this observation to my attention. |

| 5 | Newman (1998), p. 268. See Newman (2007), p. 373, for a list of scriptural references in the text. The phrase “a maximo dolore” is translated by some as “from the greatest pain,” e.g., Newman (1998), p. 99. |

| 6 | See Newman (2007), pp. 352–57 on the structure of the cycle. |

| 7 | For an example of a dissenting view on the liturgical use of Hildegard’s songs, see Scotti and Klaper (2017). |

| 8 | See Newman (2007), pp. 345–52, on the “liturgical miscellany” containing these unnotated song texts. Texts for more than half of Hildegard’s sacred songs are transmitted without any notation. |

| 9 | The unnotated texts are found in Berlin, Staatsbibliothek Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Cod. lat. qu. 835; London, British Library, Harley 1725; London, British Library, Cod. Add. 15,102; Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. 963; and the Riesencodex (in a separate section from the music collection). |

| 10 | The text is otherwise correct with the exception of its appearance in London, British Library, Harley 1725, where the word “omnia” is omitted from the third line of text. Thus “by your word created were” lacks its subject in this copy. |

| 11 | The edition is freely available at (Meconi n.d.) Honey Meconi, ed., The Compositions of Hildegard von Bingen: Editions and Translations: www.honeymeconi.com/hildegard (accessed on 1 August 2025). |

| 12 | Medieval pitch names are used in this essay: Γ A B C D E F G a b c (=middle c) d e f g aa bb cc dd. |

| 13 | Pfau and Morent (2005), pp. 147–48: Die Zuordnung der musikalischen Phrasen zu den Texteinheiten, die konsequente Ordnung der stets mit der Quinte oder der Finalis verknüpften Phrasenenden, auch die Anordnung der Tonräume in der stabilen Quinte (E-h) und Quarte (h-e), innerhalb derer sich die Phrasen entfalten, scheinen die Grundidee des Textes, der die ordnende Kraft im Herzen der Ewigkeit ergründet, auf musikalischer Ebene symbolhaft wiederzugeben. Alles an dem Gesang scheint gemessen und würdevoll: Die allmähliche Öffnung des Tonraumes, die gleichmäßig neumatische Vertonung des Textes mit jeweils drei oder vier Noten pro Silbe, die geordneten Phrasenzieltöne auf h oder E…. Der Gesang gleicht einer musikalischen Meditation über die Unbegreiflichkeit des Mysteriums der Inkarnation und trifft in seinem Ton die würdevolle Verehrung, die aus Hildegards tief empfundener Dichtung spricht. |

| 14 | Although much has been written about ornamental neumes, evidence used to establish guidelines for their performance is limited and capable of multiple interpretations. Further, much of the research on these neumes draws on manuscripts from two centuries before Hildegard’s time that originated outside of her geographical area. As a result, no scholarly consensus exists concerning these neumes or whether their performance would have differed in different parts of Europe at different times. |

| 15 | The pressus receives a single article for its multiple forms. |

| 16 | Forty-one of Hildegard’s seventy-seven songs include a signed b-flat at some point in the composition. The flat appears most often in works with A, C, or D finals, and much less frequently in works with E, G, or F finals. |

| 17 | I restricted recordings for comparison to those that used voice, since Hildegard intended her music to be sung. I wanted to contrast ensembles with an intensive connection to Hildegard’s music that nonetheless approached it differently (the first two recordings discussed); the third recording was chosen to demonstrate the great freedom and flexibility used by some individuals and ensembles in their approach to performance. |

| 18 | On the modern editing history of Hildegard’s music, see Meconi (2013). |

| 19 | For a critique of various performance and marketing choices for Hildegard’s music, see Bain (2004) and Bain (2009). |

| 20 | Timings are as follows: verse, 2:56; repetendum, 3:51; doxology, 4:43, repetendum, 5:06. |

| 21 | Timings are as follows: “et ipsum verbum,” 1:33; “que educta est,” 2:15; “et sic indumenta,” 2:30; verse, 3:50; repetendum, 4:45. |

| 22 | The nuns’ performance of a quilisma can be heard at the beginning, as can Sequentia’s performance of a quilisma spanning a third. For an example of a quilisma of a fourth, listen to the Sequentia recording at 3:25. |

| 23 | An example of repeated articulation for the nuns is :17; Sequentia’s lack of articulation is heard at :25. |

| 24 | Michael is far from unique in her exploration of vocal timbres for performing Hildegard. Ensemble Organum, to cite just one example, is noted for a similar approach. |

| 25 | Michael’s adventurous spirit is on full display in the photos on her website, where in one image she is performing while wearing a gas mask: Michael (n.d.). |

References

- Bain, Jennifer. 2004. Hildegard on 34th Street: Chant in the Marketplace. Echo: A Music-Centered Journal 6. [Google Scholar]

- Bain, Jennifer. 2009. Hooked on Ecstasy: Performance ‘Practice’ and the Reception of the Music of Hildegard of Bingen. In The Sounds and Sights of Performance in Early Music: Essays in Honour of Timothy J. McGee. Edited by Maureen Epp and Brian E. Power. Franham and Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 253–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fassler, Margot E. 2023. Cosmos, Liturgy, and the Arts in the Twelfth Century: Hildegard’s Illuminated Scivias. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hildegard of Bingen Music Research Guide. n.d. Available online: https://dact-chant.ca/hildegard.html (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Hiley, David. n.d.a. Distropha, tristropha. In Oxford Music Online. Available online: https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.ezp.lib.rochester.edu/grovemusic/display/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000007856?rskey=jpYN3a&result=1 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Hiley, David. n.d.b. Pressus. In Oxford Music Online. Available online: https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.ezp.lib.rochester.edu/grovemusic/display/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000022312?rskey=lbdPnM&result=1 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Hiley, David. n.d.c. Quilisma. Available online: https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.ezp.lib.rochester.edu/grovemusic/display/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000022699?rskey=VCIELb&result=1 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Liquescent. n.d. In Oxford Music Online. Available online: https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.ezp.lib.rochester.edu/grovemusic/display/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000016740?rskey=vtwbuH&result=1 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Meconi, Honey. 2013. The Unknown Hildegard: Editing, Performance, and Reception (An Ordo virtutum in Five Acts). In Music in Print and Beyond: Hildegard von Bingen to The Beatles. Edited by Craig A. Monson and Roberta Montemorra Marvin. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, pp. 258–305. [Google Scholar]

- Meconi, Honey, ed. n.d. The Compositions of Hildegard von Bingen: Editions and Translations. Available online: www.honeymeconi.com/hildegard (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Mews, Constant. 1998. Religious Thinker: “A Frail Human Being” on Fiery Life. In Voice of the Living Light: Hildegard of Bingen and Her World. Edited by Barbara Newman. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, pp. 52–69, 209–13. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, Kristia. n.d. Website. Available online: https://kristiamichael.com/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Newman, Barbara. 1987. Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Barbara. 1998. Saint Hildegard of Bingen: Symphonia—A Critical Edition of the Symphonia Armonie Celestium Revelationum [Symphony of the Harmony of Celestial Revelations], 2nd ed. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Barbara. 2007. Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum. In Hildegardis Bingensis: Opera Minora. Edited by Peter Dronke, Christopher P. Evans, Hugh Feiss, Beverly Mayne Kienzle, Carolyn A. Muessig and Barbara Newman. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 226. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 335–477. [Google Scholar]

- Oriscus. n.d. In Oxford Music Online. Available online: https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.ezp.lib.rochester.edu/grovemusic/display/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000020467?rskey=sFsc5j&result=1 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Pfau, Marianne Richert. 1990. Mode and Melody Types in Hildegard von Bingen’s Symphonia. Sonus: A Journal of Investigations into Global Music Possibilities 11: 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Pfau, Marianne Richert, and Stefan Morent. 2005. Hildegard von Bingen: Der Klang des Himmels. Europäische Komponistinnen 1. Cologne, Weimar, and Vienna: Böhlau Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Scotti, Alba, and Michael Klaper. 2017. Redaktion und Liturgisierung: Zu den Psalmtonangaben in der Überlieferung der Gesänge Hildegards von Bingen. Die Musikforschung 70: 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virga Strata. n.d. In Oxford Music Online. Available online: https://www-oxfordmusiconline-com.ezp.lib.rochester.edu/grovemusic/display/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000052896?rskey=VXPs3n&result=1 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).