From Mountains and Forests to the Seas: The Maritime Spread of the Sanping Patriarch Belief

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Origins and Early Development of the Sanping Patriarch Belief

3. The Sanping Patriarch Belief in Taiwan

3.1. Transmission Routes and Major Branch Temples in Taiwan

3.2. Localization of the Belief in Taiwan

3.3. Interaction with the Ancestral Temple in Taiwan

- Pilgrimage to the ancestral temple. Numerous Sanping Patriarch branch temples in Taiwan regularly or irregularly organize pilgrimages for devotees to the ancestral temple. For example, the Sanping Guangji Temple 三平廣濟宮 in Tainan City has made multiple pilgrimages to the Pinghe ancestral temple. In 1988, devotees at this temple witnessed the Serpent Attendant and Tiger Attendant at the ancestral temple. Upon returning to Taiwan, they crafted statues of the attendants based on photos from the ancestral temple for enshrinement and worship.19 This process not only perpetuated the ancestral belief but also deepened cultural ties across the Taiwan Strait.

- Exchange and interaction. Beyond pilgrimages from Taiwanese branch temples to the ancestral temple, the ancestral temple organized cultural exchange delegations to Taiwan in 2009 and 2013. Additionally, in 2009, the “Cross-Strait (Pinghe) Sanping Patriarch Cultural Association” was established to promote exchanges and cooperation between the two sides. Taiwanese branch temples actively participate in various celebratory events hosted by the ancestral temple, such as Sanping Patriarch cultural folk (intangible cultural heritage) activities. This bidirectional interaction not only reconstructs the close relationship between the main temple and its branches but also strengthens Taiwanese devotees’ cultural identification with their ancestral homeland through the belief network.

4. The Sanping Patriarch Belief in Southeast Asia

4.1. Transmission Routes and Major Branch Temples in Southeast Asia

4.2. Localization of Belief in Southeast Asia

4.3. Interaction with the Ancestral Temple in Southeast Asia

5. Discussion

5.1. Commonalities

5.2. Differences

- Differences in transmission mechanisms. In Fujian, the propagation of the Sanping Patriarch belief has been driven mainly by local government initiatives, including heritage branding, scenic site management, and festival-based cultural promotion. As Chia (2022, p. 88) has noted, “the Sanping Patriarch belief became an invented tradition during this period for expanded religious tourism in Pinghe County.” In Taiwan, the transmission is centered on clan networks and community integration, with the belief serving as an essential bond that sustains internal cohesion within kinship groups and facilitates external social relations. In Southeast Asia, dissemination has depended on commercial networks and migrant communities, where the belief has transcended ethnic boundaries through cultural adaptation in multi-ethnic societies. Such variations illustrate how social structures and contextual conditions shape the pathways of religious transmission.

- Differences in the sources of devotees. At the ancestral temple, devotees are primarily concentrated in traditional centers of belief such as Zhangzhou, Quanzhou, and Chaozhou in Guangdong. In Taiwan, the followers primarily consist of descendants of Zhangzhou and Quanzhou immigrants, continuing a strong sense of ancestral-place identity. In Southeast Asia, however, due to the region’s multi-ethnic social structure, the multi-ethnic outreach extends beyond the Chinese diaspora. For example, Indian visitors at Poh Onn Kong Temple in Malacca participate in the Patriarch’s birthday celebrations and engage in practices such as incense offerings and divination. In Jakarta, the Vihara Khema Tjouw Soe Kong Temple attracts non-Chinese communities—including Muslims—by incorporating local deities such as Ibu Eneng, blending cultural elements to foster broader appeal. Thus, the sources of devotees not only reflect historical migration patterns but also shape the strategies of religious dissemination.

- Differences in the interpretation of mythological symbols. Both Fujian and Taiwan continue the tradition of venerating the Serpent and Tiger Attendants as guardian figures of the Patriarch, primarily tasked with protecting devotees by patrolling territories, warding off evil, and ensuring safety. In Taiwan, these figures have further evolved through localized myth-making, such as incorporating the historical figure Yang Wulang into the Patriarch’s narrative. In Southeast Asia, however, due to a rupture in the transmission of the attendant deities and the absence of supporting mythological narratives, these figures are retained more as symbolic representations of ancestral temple culture rather than active components of local religious imagination. This comparison highlights the profound influence of local history on the depiction and functions of mythological figures.

- Differences in divine roles and functions of the Patriarch. In the ancestral temple in Fujian, the Sanping Patriarch is worshipped primarily as both a rain deity and a healing deity, retaining a distinct divine identity. In Taiwan, however, joint worship with other Patriarchs—such as Qingshui Patriarch—has led to a blurring of his original divine roles. Additionally, historical migration has endowed him with a unique function as a maritime protector. In Southeast Asia, the Patriarch is worshipped alongside local deities such as Datuk Gong and Embah Said Areli Dato Kembang but still maintains his independent divine status. These differences reveal the dynamic nature of divine attributes, which continuously evolve through regional interactions and multicultural exchanges.

- Differences in core ritual practices. The ancestral temple in Fujian strictly adheres to the traditional “Three Sixes” ritual calendar in commemorating the Patriarch. In contrast, some branch temples in Taiwan do not follow the birthday date of the Patriarch as set by the ancestral temple. For instance, Fei’an Temple in Danei celebrates the deity’s birthday on the eighth day of the fourth lunar month. Such adjustments reflect both the need to accommodate local circumstances and the incorporation of innovative elements. For example, Sanping Temple in Zhushan Township has introduced modern performances—such as the Techno Prince Parade dance and contemporary song-and-dance shows—into its birthday celebrations, successfully attracting younger generations. Temples in Southeast Asia, on the other hand, continue to observe the original date of the sixth day of the sixth lunar month. At the same time, they adapt traditions through ritual reinvention—for instance, combining the turtle petitioning ritual with charitable activities. While both Taiwan and Southeast Asia sustain the vitality of belief through innovation, the former emphasizes cultural continuity, whereas the latter prioritizes the expansion of social functions. This comparison indicates that ritual practices mediate the tension between traditional continuity and contemporary needs.

- Differences in the transformation of social functions. In Fujian, the modernization of the Sanping Patriarch belief has been led by local government efforts, incorporating it into the intangible cultural heritage system and promoting the conversion of religious resources into economic capital. At the same time, the core “Sanping” spirit has been reinterpreted with modern values—such as “peace of mind, equality for all beings, and a lifetime of safety” (Zhou 2025, p. 99)—to align with contemporary social governance objectives. With administrative support and financial resources, the influence of the belief has been significantly expanded. In Taiwan, branch temples rely on clan-based networks and operate under community self-governance models that strengthen local identity. While this model limits broader influence, it maintains intense grassroots penetration through close-knit community ties. In Southeast Asia, the belief has evolved into a public religion by promoting interethnic integration through charitable and community service activities. Despite the absence of official funding, its vitality is sustained through flexible practices—such as spreading belief content via short videos on TikTok and organizing mutual aid programs—ensuring the continued relevance of the Sanping Patriarch belief within multicultural societies. The social functions of this belief show that religious institutions adapt strategically while preserving their cultural core.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | As encapsulated in the principle yougong ze si (有功則祀, those with merit shall be worshipped), the Liji (Book of Rites) prescribes sacrificial honors for five categories of merit: “法施于民則祀之 (lawgivers), 以死勤事則祀之 (diligent martyrs), 以勞定國則祀之 (state stabilizers), 能禦大災則祀之 (calamity averters), 能捍大患則祀之 (disaster resisters)” Liji·Jifa (《礼记·祭法》). |

| 2 | Dong Ligong identified three characteristics of the belief in the Sanping Patriarch in Taiwan: First, followers of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism all worship the Sanping Patriarch, and they even mix their respective deities with him in joint rituals. Second, while the establishment of Sanping Patriarch temples in Taiwan began early, their development was slow. Third, the belief in the Sanping Patriarch is more widespread in southern Taiwan than in the north and central regions, which is closely related to the migration routes of Zhangzhou immigrants to Taiwan. The author did not further analyze the reasons for the slow development of Sanping Patriarch temples in Taiwan (Dong 2013, pp. 29–32). |

| 3 | Hsieh analyzed the origins of the belief in the Sanping Patriarch in Taiwan and the types of rituals associated with his worship in Taiwan. However, the study did not compare the belief and worship of the Sanping Patriarch in Taiwan with that in Fujian (Hsieh 2017). |

| 4 | Chang introduced several Sanping Patriarch temples in Taiwan and analyzed the differences between the Sanping Patriarch temples in Taiwan and those in Fujian. The differences highlighted include the following: first, not all Sanping Patriarch temples in Taiwan enshrine the attendants; second, the depictions of Sanping Patriarch and the attendants differ from those in Fujian temples; and third, the celebration dates of the Patriarch’s birthday vary. However, the author did not elaborate on the reasons for these differences (Chang 2020). |

| 5 | Yan analyzes the formation, development, and influencing factors of the Sanping Patriarch belief. She outlines its dissemination path and explores its modern transformation in connection with the tourism industry. Her research adopts a linear historical narrative, whereas my study moves beyond this linear approach by introducing the analytical tools of “orthodoxy preservation” and “localized innovation” to conduct a comparative regional analysis (Yan 2001, pp. 114–20). |

| 6 | Hsieh’s research provides a systematic examination of the development of the Sanping Patriarch belief. He begins by analyzing the formation, evolution, and dissemination of the belief. Then he focuses on the Taiwanese context by tracing the historical lineages of local temples to clarify the trajectory of its development. Finally, by comparing the ancestral temple in mainland China with its branch temples in Taiwan—particularly in terms of incense transmission, pantheon composition, temple naming practices, and birthday celebrations—Hsieh identifies the unique features of the Sanping Patriarch belief in Taiwan and offers an in-depth analysis of the factors contributing to its localized formation (Hsieh 2025). |

| 7 | Song’s research provides a historical account of Poh Onn Kong Temple, Zhong Anting Temple, and the Zhangzhou Clan Association in Malacca. By examining the origins of the deities worshipped at Zhong Anting Temple and the native places of temple staff, he infers that the majority of devotees likely came from the southern Fujian region, particularly from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou (Song 2025). |

| 8 | Tan’s study constructs the pantheon position of the Sanping Patriarch. It offers a historical overview of Poh Onn Kong Temple, the Chiang Chew Association, and Chong Ann Teng Temple in Malacca, along with the deities worshipped in these institutions. Notably, she provides a detailed discussion of the Tudi Gong (Earth Deity) venerated at these sites. Tan argues that traditional Chinese religious beliefs continue to constitute the dominant belief system within Malaysian Chinese communities today (Tan 2025). |

| 9 | Zheng Laifa provides a historical account of Poh Onn Kong Temple and analyzes its ritual network and historical transformations through the use of inscriptional evidence from the temple’s renovation steles (Zheng 2025). |

| 10 | Serpent Attendant: In the main hall and pagoda hall of Sanping Temple in Pinghe County, two standing attendants are placed beside the deity of Sanping Patriarch. The Serpent Attendant has both hands in a prayer position, glaring fiercely, exuding an aura of dignity and power; the Tiger Attendant bares its fangs, with a fierce expression, holding a magical staff and watching menacingly. According to legend, when Sanping Patriarch first arrived at Sanping Mountain, while working in the vegetable garden, a serpent would often circle him and refuse to leave. One day, the Patriarch asked the serpent, “Are you a spirit snake? If so, nod your head.” The serpent nodded three times, and the Patriarch took it back to the temple to tame it. Later, the spirit not only caught rats but also protected the villagers. The local people grew fond of the spirit and carved the statue of the Serpent Attendant to be placed beside the statue of Sanping Patriarch for worship (Lu 2008, p. 117). |

| 11 | Tiger Attendant: According to legend, a colorful, thousand-year-old tiger monster appeared in the Sanping Tiger Forest. Due to its failed cultivation, it often came out to harm humans and livestock. When Sanping Patriarch captured it, it suddenly begged for mercy. Sanping Patriarch took it back to the temple, tamed it, and made it his attendant. From then on, the Tiger Attendant protected the peace of the surrounding areas. Grateful for its contributions, the people carved a statue of the Tiger Attendant and placed it beside the statue of Sanping Patriarch for veneration (Lu 2008, p. 119). |

| 12 | The Bamin Tongzhi (General Gazetteer of the Eight Min), under the section on “Mountains and Rivers”, describes: “Sanping Mountain is characterized by deep and rugged valleys. Those who ascend must pass through three dangerous areas before reaching the summit, which is why it is named Sanping. The Tang monk Yizhong built the Sanping Temple. At the top, there are the Turtle and Serpent Peaks (Guishe Feng 龜蛇峰), Immortal Pavilion (Xianren Ting 仙人亭), Monk’s Pool (Heshang Tan 和尚潭), Nine-Layer Rock (Jiuceng Yan 九層岩), Twin Horn Mountain (Shuangji Shan 雙髻山), Gao Ke Ridge (Gaoke Ling 高柯嶺), Tea Boiling Hollow (Jiancha Wu 煎茶塢), Minister’s Pavilion (Shilang Ting 侍郎亭), Tiger Claw Spring (Hupa Quan 虎爬泉), Staff Tree (Xizhang Shu 錫杖樹), and Great Uncle Mountain (Dabo Shan 大伯山), making a total of eleven wonders” (Huang 2006, p. 210). |

| 13 | During the Ming Xuande 宣德 reign, in order to pray for rain, the statue of Sanping Patriarch was brought by the villagers, and when passing through Fushan Zongdapingshe, they stopped and did not continue. Later, the villagers built a temple to enshrine the statue of the ancestor. In times of drought, they would pray for rain in front of the statue. If they received permission, they would carry the statue around the surrounding area, and rain would come every time, without fail. 明宣德間因迎師像祈雨,過浮山總大坪社,遂止不去,鄉人築寺祀之。遇旱向像前乞茭可,則擁像繞境,呼雨無不應者 (Yao and Li 2000, p. 401). |

| 14 | In the Wanli 萬曆 reign, Wang Zhidao 王志道 also visited Sanping Temple to pray for a child, and he received a miraculous result. It is found in his 1607 colophon appended to the stele. See Wang Feng, Stele of the Reconstruction Records of Master Guangji of Sanping, in Zheng and Dean, eds., Compilation of Religious Inscriptions from Fujian (Zhangzhou Prefecture Volume), 1507. |

| 15 | In the tenth year of the Ming Xuande 宣德 reign (1435), a plague ravaged Shancheng 山城. The residents respectfully invited the Guangji Patriarch from Pinghe Sanping Temple to arrive, where he provided medical treatment and dispensed medicine, saving countless lives. In the second year of the Ming Zhengtong 正統 reign (1437), a temple was built in the middle section of Mai Zai Street 麥仔街 in the city to enshrine and worship the deity of Sanping Patriarch. |

| 16 | According to the Stele Inscription of Li Muqing’s Donation of Paddy Rent for the Lamp Offerings to Zushi Gong and Marshal Temple (Li Muqing Xishe Tianzu Fengwei Zushigong Yuanshuaige Xiangdeng Beiji) dated to the 18th year of the Qianlong reign (1753), Li Muqing donated land to support lamp offerings at the Anjiao Zhongzhuang Zushigong Temple (present-day Sanping Temple in Xiyan Village, Yanchao District, Kaohsiung) and the Marshal Temple. This indicates that the Sanping Zushigong Temple already existed before the stele’s erection. The inscription thus stands as the earliest known documentary evidence of a Sanping Patriarch temple in Taiwan (National Central Library, Taiwan Branch 1784). |

| 17 | The “Three Sixes” refer to the three commemorative dates of Sanping Patriarch, which are: the sixth day of the first lunar month, marking his birth anniversary; the sixth day of the sixth lunar month, commemorating his ordination; and the sixth day of the eleventh lunar month, marking the anniversary of his liberation from wordly existence. |

| 18 | In 1959, the temple construction committee raised a total of 40,000 yuan, and the temple was completed that same year. See http://www.nanchens.com/qszs/qzsz03/qzsz03034.htm. (accessed on 31 October 2024). |

| 19 | Interview with Mr. Lin, Sanping Guangji Temple, Tainan City, via WeChat, 20 June 2025. |

| 20 | |

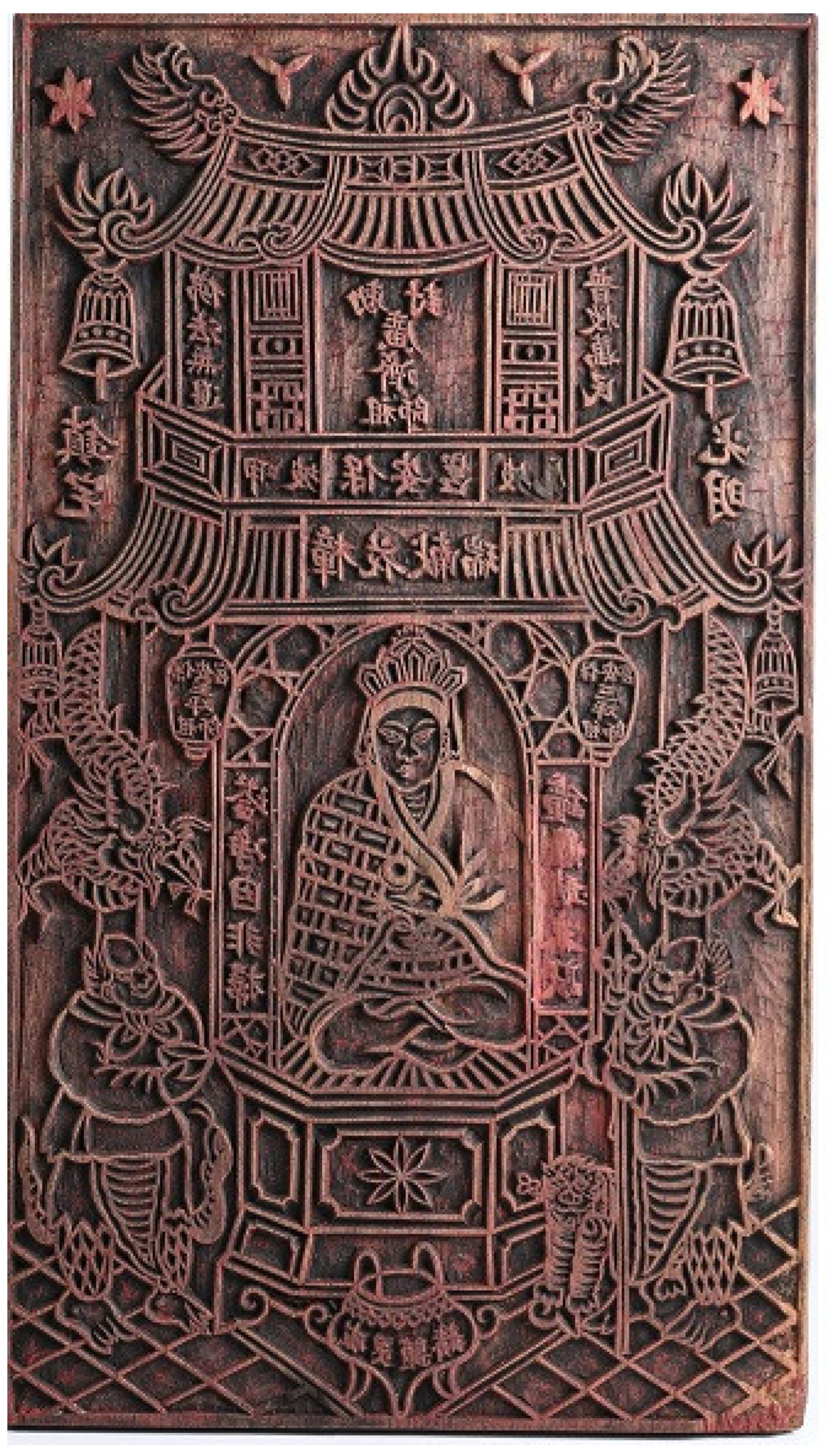

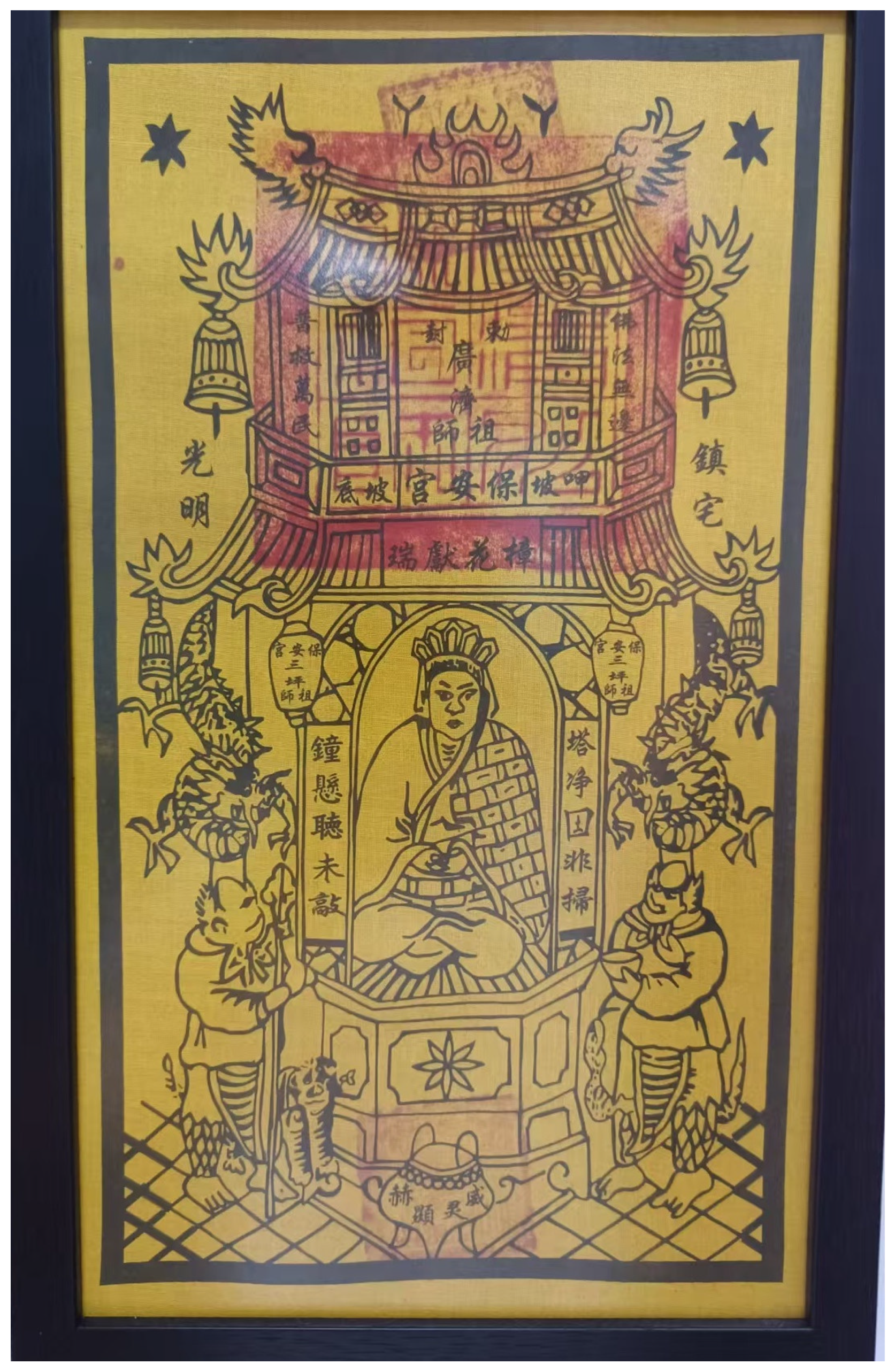

| 21 | The following description proceeds from the top downward and from the center outward. (1) Main Plaque and Deity. The central vertical plaque reads “Imperially Bestowed Title: Guangji Patriarch” (勅封廣濟祖師), a Tang-dynasty honorific that identifies the principal deity as the Sanping Patriarch. (2) Upper Couplets. Right couplet: “The Dharma Is Boundless” (佛法無邊). Left couplet: “Universally Delivering All Beings” (普救萬民). These lines extol the infinite scope of the Buddha’s teaching and its universal salvific power. (3) Side Inscriptions of Blessing. Upper right: “Protecting the Household” (鎮宅), expressing a wish for domestic safety. Upper left: “Radiant Light” (光明), invoking purity and auspicious illumination. (4) Architectural Details. The roof plaques bear the local place-names “Gapo” (呷坡) and “Podi” (坡底), indicating the Malacca location of the Poh Onn Kong Temple (保安宫). The central horizontal plaque reads “Fragrant Camphor Offers Auspiciousness” (樟花獻瑞), a phrase also found in the Fujian ancestral temple, highlighting the close link between the two sites. Lanterns on either side read “The Sanping Patriarch of Poh Onn Kong Temple” (保安宮三坪祖師), confirming the deity venerated. (5) Couplet beside the Patriarch. Right: “The Pagoda Is Pure Not Because It Is Swept” (塔淨因非掃). Left: “The Bell Hangs Though Not Yet Struck” (鐘懸聽未敲). This expresses Chan (Zen) thought: true purity arises from the mind itself, yet realization still calls for deliberate practice. (6) Incense Burner Inscription. The front bears “Majestic and Manifest Spirit Power” (威靈顯赫), signifying the deity’s potent and evident divine authority. Overall, this talisman embodies the fusion of Buddhist and local folk traditions, conveying prayers for household safety, spiritual clarity, and the protective presence of the Sanping Patriarch. |

| 22 | While Susilo (2024) links the temple’s location to health, feng shui, and Quanzhou patrons and identifies Qingshui Patriarch as its main deity, earlier research by Setiawan and Hay (1990, p. 282) confirms that the deity is Guangji Patriarch (Sanping Patriarch). |

| 23 | The “Begging Turtle” (乞龜) is a life-like turtle shape constructed from bags of white rice, each with a fixed weight. The structure is carefully arranged with a Seven Stars Formation on both sides of the turtle and in front of the temple gates. After the consecration ceremony, the directors and devout believers begin to touch the turtle to pray for blessings. The ritual requires participants to follow a clockwise direction, starting at the turtle’s head, and circling to touch its entire body. Touching the head symbolizes the beginning of prosperity, touching the legs represents rising in status, caressing the shell signifies longevity, and touching the tail signifies abundant wealth. At the end of the ceremony, the devotees cleanse their hands in the Seven Stars Formation’s well, a gesture symbolizing prosperity and the successful completion of their wishes. |

References

- Amrith, Sunil S. 2013. Crossing the Bay of Bengal: The Furies of Nature and the Fortunes of Migrants. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Chi-Shiang 張志相. 2010. Taiwan Sanping Zushi Xinyang Qiyuan Wenti Xintan—Sanping Yizhong Yu Sanpingsi 臺灣三平祖師信仰起源問題新探—三平義中與三平寺 [New Findings on the Origin of Belief in the San Ping Master in Taiwan]. Shumin Wenhua Yanjiu 庶民文化研究 Journal for Studies of Everyday Life 2: 37–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Chi-Shiang 張志相. 2020. Taiwan Minjian Xinyang De Fojiao Yinyuan—Sanping Yu Cankui Zushi Yanjiu 臺灣民間信仰的佛教因緣—三坪與慚愧祖師研究 [Buddhist Affinities in Taiwanese Folk Beliefs: A Study of Sanping and the Cankui Patriarch]. Taichung: Fengrao Cultural Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Pin-Tsun. 2019. The rise of Chinese mercantile power in maritime Southeast Asia, c. 1400–1700. In China and Southeast Asia: Historical Interactions. Edited by Geoff Wade and James k. Chin. London: Routledge, pp. 221–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, Jack Meng-Tat. 2022. The Making of a Local Deity: The Patriarch of Sanping’s Cult in Post-Mao China, 1979–2015. Critical Asian Studies 54: 86–104. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Ligong 董立功. 2013. Taiwan Sanping Zushi Xinyang Chutan 臺灣三平祖師信仰初探 [An initial exploration of the belief in Sanping Patriarch in Taiwan]. Fujian Shizhi 福建史志 Fujian Historical Gazetteer 1: 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, Wolfgang, and Tieh Fan Chen, eds. 1982. Chinese Epigraphic Materials in Malaysia 馬來西亞華文銘刻彙編. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fukami, Sumio. 2004. The long 13th century of Tambralinga: From Javaka to Siam. Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko 62: 45–79. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Zhichao 郭志超. 2013. Sanping Zushi Jiansi Yu Sanping Chongshe Xintan 三平祖師建寺與三坪崇蛇新探 [The Construction of Temples by Sanping Patriarch and a New Exploration of the Sanping Serpent Worship]. Mintai Wenhua Yanjiu 閩台文化研究 Fujian-Taiwan Cultural Research 3: 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Valerie. 1990. Changing Gods in Medieval China, 1127–1276. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heuken, Adolf. 1989. Historical Sights of Jakarta, 3rd ed. Petaling Jaya: Times Books International. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Kuei-wen 謝貴文. 2025. Sanping Zushi Xinyang Zai Taiwan De Fazhan Yu Tese 三平祖師信仰在臺灣的發展與特色 [Sanping Patriarch belief in Taiwan: Development and characteristics]. In Sanping Zushi Wenhua Yanjiu 三平祖師文化研究 [Studies on Sanping Patriarch Culture]. Edited by Yun Liu and Wenshen Lu. Hong Kong: Chinese Review Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, Yu-mei 謝玉美. 2017. Sanping Zushi Xinyang Jiqi Zai Taiwan De Fazhan 三平祖師信仰及其在臺灣的發展 [The Worship of San-ping Zushi and Its Later Development in Taiwan]. Master’s thesis, Hsuan Chuang University, Hsinchu, Taiwan, China. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Jinwang 胡金望. 2011. Sanpingsi Wenhua Jiedu 三平寺文化解讀 [An Interpretation of Sanping Temple Culture]. Zhangzhou Shifan Xueyuan Xuebao(Zhexue Shehui Kexue Ban) 漳州師範學院學報 (哲學社會科學版) Journal of Zhangzhou Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 25: 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Pingsheng 胡平生, and Meng Zhang 張萌, trans. 2017. Liji 禮記 [The Book of Rites]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Zhongzhao 黃仲昭. 2006. Bamin Tongzhi 八閩通志 [General Gazetteer of the Eight Min]. Fuzhou: Fujian People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Guoping 林國平, and Jiduan Qiu, eds. 2005. Fujian Yimin Shi 福建移民史 [History of Fujian Immigration]. Beijing: Fangzhi Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Meirong 林美容. 2000. Xiangtushi Yu Cunzhuangshi: Renlei Xuezhe Kan Difang 鄉土史與村莊史:人類學者看地方 [Local and Village History: Anthropologists on Localities]. Taipei: Taiwan Yuan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Wenshen 盧文深, ed. 2025. Xinbian Sanping Sizhi 新編三平寺志 [New Gazetteer of Sanping Temple]. Hong Kong: China Review Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Zhenhai 盧振海, ed. 2008. Sanping Sizhi 三平寺志 [Sanping Temple Gazetteer]. Zhangzhou: Sanping Scenic Area Management Committee of Pinghe County, Fujian. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Zhenhai 盧振海, ed. 2010. Sanping Zushi Fenling Lu 三平祖師分靈錄 [The Record of the Distribution of the Sanping Patriarch’s Spirit Tablets]. Zhangzhou: Pinghe County Sanping Scenic Area Management Committee. [Google Scholar]

- National Central Library, Taiwan Branch. 1784. Limuqing Xishe Tianzu Fengwei Zushigong Yuanshuaiye Xiangdeng Beiji 李穆清喜捨田租奉為組師西元帥爺香燈碑記 [Li Muqing’s donation of land rent for the Patriarch and Marshal’s lamp worship: A stele inscription]. In Taiwan Memory Digital Archives. Taipei: National Central Library. Available online: https://tm.ncl.edu.tw/article?u=014_001_0000000517 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- National Central Library, Taiwan Branch. 1833. Sanpinggong Shendan Yanxi Juanti Beiji 三坪宮神誕演戲捐題碑記 [Sanping Temple deity’s birthday performance and donation stele]. In Taiwan Memory Digital Archives. Taipei: National Central Library. Available online: https://tm.ncl.edu.tw/article?u=014_001_0000000518 (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- National Central Library, Taiwan Branch. 1835. Guangji Zushi Miaochan Beiji 廣濟祖師廟產碑記 [Inscription of Guangji Patriarch Temple property]. In Taiwan Memory Digital Archives. Taipei: National Central Library. Available online: https://tm.ncl.edu.tw/article?u=014_001_0000006822 (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Sen, Tansen. 2011. Maritime interactions between China and India: Coastal India and the ascendancy of Chinese maritime power in the Indian Ocean. Journal of Central Eurasian Studies 2: 41–82. [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan, Deddy. 2024. Multikulturalisme: Tinjauan penggolongan dewa pengharapan di Kelenteng Toasebio Jakarta [Multiculturalism: Classification review of hope deities in Toasebio Temple, Jakarta]. Archaeology Nexus: Journal of Conservation and Culture 1: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan, E., and Kwa Thong Hay. 1990. Dewa-Dewi Kelenteng [Temple Deities]. Semarang: Yayasan Kelenteng Ampookong. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Yilong 石奕龍. 2004. Sanping Zushi Xiang Zhongsui De Chuanshuo Jiqi Xiangzheng Yiyi 三平祖師降”眾祟”的傳說及其象徵意義 [The Legend of Sanping Patriarch Subduing “Evil Spirits” and Its Symbolic Meaning]. Taiwan Yuanliu 臺灣源流 Taiwan Heritages 29: 136–39. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Yanpeng 宋燕鵬. 2025. Sanping Zushi Xinyang Zai Malai Xiya De Fazhan Yu Liuchuan 三坪祖師信仰在馬來西亞的發展與流傳 [The development and transmission of Sanping Patriarch belief in Malaysia]. In Sanping Zushi Wenhua Yanjiu 三平祖師文化研究 [Studies on Sanping Patriarch Culture]. Edited by Yun Liu and Wenshen Lu. Hong Kong: Chinese Review Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Dan 蘇丹. 2025. Huashe Chengshen:Sanping Zushi Xinyang Zhong She Shizhe Xingxiang Yanjiu 化蛇成神:三平祖師信仰中蛇侍者形象研究 [From snake to deity: A study on the snake attendant in the belief of Sanping Patriarch]. In Sanping Zushi Wenhua Yanjiu 三平祖師文化研究 [Studies on Sanping Patriarch Culture]. Edited by Yun Liu and Wenshen Lu. Hong Kong: Chinese Review Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Yuanzhi 孫源智. 2012. Luelun Sanping Zushi Xinyang De Chuanbo Yu Kuosan 略論三平祖師信仰的傳播與擴散 [A Brief Discussion on the Spread and Diffusion of Sanping Patriarch’s Worship]. Mintai Wenhua Jiaoliu 閩台文化交流 Min-Tai Cultural Exchange 3: 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Susilo, Greysia. 2015. Jakarta’s Chinese temples until 1949: Socio cultural sites. Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference on Chinese Indonesian Studies, Universitas Kristen Maranatha, Bandung, Indonesia, February 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Susilo, Greysia. 2024. Deity without culture: Inclusivity practice of Chinese religion in DKI Jakarta. Paper presented at the International Forum on Spice Route 2024, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Jakarta, Indonesia, September 23–26; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385812592 (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Tan, Ai Boay 陳愛梅. 2025. Sanping Zushi Zai Malai Xiya Huaren Chuantong Xinyang Zhong De Shenpu Weizhi 三坪祖師在馬來西亞華人傳統信仰中的神譜位置 [The Pantheon Position of Sanping Patriarch in the traditional beliefs of Malaysian Chinese]. In Sanping Zushi Wenhua Yanjiu 三平祖師文化研究 [Studies on Sanping Patriarch Culture]. Edited by Yun Liu and Wenshen Lu. Hong Kong: Chinese Review Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Ai Boay 陳愛梅, and Teong Chuan Toh 杜忠全. 2021. Fanshen Tanghua—Malai Xiya Nadu Gong Xinyang 番神唐化—馬來西亞拿督公信仰 [Sinicization of Foreign God—The Study of Datuk Kong Belief in Malaysia]. Taibei Daxue Zhongwen Xuebao 臺北大學中文學報 Journal of Chinese Language and Literature of National Taipei University 30: 601–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Chee-Beng. 2020. Chinese Religion in Malaysia: Temples and Communities. Leiden: Brill, vol. 12, p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, Geoff. 2009. An early age of commerce in Southeast Asia, 900–1300 CE. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 40: 221–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Feng 王諷. 1986. Zhangzhou Sanping Dashi Beiming Bingxu 漳州三平大師碑銘並序 [Epitaph and preface for Master Sanping of Zhangzhou]. In Tang Wen Cui 唐文粹 [Selected Tang Essays]. Edited by Yao Xuan 姚鉉 and Zeng Xu 許增. Hangzhou: Zhejiang People’s Publishing House, vol. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Feng 王諷. 2018. Stele of the Reconstruction Records of Master Guangji of Sanping 重建三平廣濟大師行錄碑 [Erected in 1607, Wanli 35th year of Ming Dynasty]. In Compilation of Religious Inscriptions from Fujian (Zhangzhou Prefecture Volume). Edited by Zhenman Zheng and Kenneth Dean [Ding Hesheng]. Fuzhou: Fujian People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Guanyu. 2019. Chinese porcelain in the Manila galleon trade. In Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaports and Early Maritime Globalization. The Archaeology of Asia-Pacific Navigation 2. Edited by Chunming Wu, Roberto Junco Sanchez and Miao Liu. Singapore: Springer, pp. 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Rongguo 王榮國. 1997. Fujian Fojiao Shi 福建佛教史 [A History of Buddhism in Fujian]. Xiamen: Xiamen University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xiang 王相, and Tianjin Chang 昌天錦, eds. 2000. Kangxi Pinghe xianzhi 康熙平和縣誌 [Kangxi Pinghe county gazetteer]. In Zhongguo Difangzhi Jicheng (Fujianfu Xianzhi Ji) 中國地方誌集成 (福建府縣誌輯) [Collection of Chinese Local Gazetteers (Fujian Prefecture and County Gazetteers Volume)]. Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhaoyuan, Danny Wong Tze Ken, and Welyne Jeffrey Jehom. 2020. The Alien Communal Patron Deity: A Comparative Study of the Datuk Gong Worship among Chinese Communities in Malaysia. Indonesia and the Malay World 48: 206–24. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Guoliang 翁國梁. 1935. Zhangzhou Shiji 漳州史跡 [Historical Sites of Zhangzhou]. Fuzhou: Fujian Xiehe University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Bing’an 烏丙安. 1995. Zhongguo Minjian Xinyang 中國民間信仰 [Chinese Folk Religion]. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jifei 吳季霏. 2001. Songyuan Yiqian Fujian Minjian Xinyang Zhong Zaoshen Yu Chuanshuo De Guanxi—Yi Dingguang Gufo, Sanping Zushi, Qingshui Zushi Wei Hexin 宋元以前福建民間信仰中造神與傳說的關係—以定光古佛、三平祖師、清水祖師為核心 [The relationship between deity-making and legends in Fujian folk beliefs before the Song-Yuan period: Focusing on Dingguang Buddha, Sanping Patriarch, and Qingshui Patriarch]. Zhongguo Senhua Yuekan 中國文化月刊 [Chinese Culture Monthly] 250: 24–45. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Yiqiu 向憶秋. 2025. Shengehua, Yingxionghua, Shisuhua: Qianlun Minnan De Simiao Yu Shenming Chuanshuo 神格化、英雄化、世俗化:淺論閩南的寺廟與神明傳說 [Deification, heroization, and secularization: A brief discussion on temples and deity legends in Southern Fujian]. In Sanping Zushi Wenhua Yanjiu 三平祖師文化研究 [Studies on Sanping Patriarch Culture]. Edited by Yun Liu and Wenshen Lu. Hong Kong: Chinese Review Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Yayu 顏亞玉. 2001. Minnan Sanping Zushi Xinyang De Xingcheng Yu Fazhan Yanbian 閩南三平祖師信仰的形成與發展演變 [The Formation and Development of the Sanping Patriarch’s Belief in Southern Fujian]. Shijie Zongjiao Yanjiu 世界宗教研究 Studies in World Religions 3: 114–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Xunyi 姚循義, and Zhengyao Li 李正曜, eds. 2000. Qianlong Nanjing Xianzhi 乾隆南靖縣誌 [Qianlong Nanjing County gazetteer]. In Zhongguo Difang Zhi Jicheng (Fujianfu Xianzhi Ji) 中國地方誌集成(福建府縣誌輯) [In Collection of Chinese local Gazetteers (Fujian Prefecture and County Gazetteers Volume)]. Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Laifa 鄭來發. 2025. Maliujia Baoangong Yu Zhangzhou Sanpingsi 馬六甲保安宮與漳州三平寺 [Poh Onn Kong Temple in Malacca and Zhangzhou Sanping Temple]. In Sanping Zushi Wenhua Yanjiu 三平祖師文化研究 [Studies on Sanping Patriarch Culture]. Edited by Yun Liu and Wenshen Lu. Hong Kong: Chinese Review Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Guolin 周國林. 2025. Qiannian Gucha Sanpingsi Cong “Chanzong Daochang” Dao “Minnan Shendian” De Yanhua 千年古刹三平寺從“禪宗道場”到“閩南神殿”的演化 [The Evolution of the Ancient Sanping Temple from “Zen Buddhist Site” to “Southern Fujian Deity Shrine”]. In Sanping Zushi Wenhua Yanjiu 三平祖師文化研究 [Studies on Sanping Patriarch Culture]. Edited by Yun Liu and Wenshen Lu. Hong Kong: Chinese Review Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Temple Name | Establishment Time | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yanchao Sanping Temple | pre-1753 | Yanchao Dist., Kaohsiung |

| 2 | Zhushan Sanping Temple | 1789 | Nantou County, Taichung |

| 3 | Hua’an Temple (Guangji Palace) | 1797 | Baihe Dist., Tainan |

| 4 | Sanping Patriarch Temple, Talu | 1810 | Ligang Township, Pingtung |

| 5 | Jixin Yongan Temple | 1861 | Wujie Township, Yilan |

| 6 | Qianzhen Sanlong Temple | Guangxu era (1875–1908) | Qianzhen Dist., Kaohsiung |

| 7 | Danei Feian Temple | 1883 | Danei Dist., Tainan |

| 8 | Nanchang Guangzhou Temple | 1951 | West Central Dist., Tainan |

| 9 | Xinguang Sanlong Temple | 1964 | Qishan Dist., Kaohsiung |

| 10 | Xikou Zushigong Temple | 1966 | Xikou Township, Chiayi County |

| 11 | Tianzhong Sanping Temple | 1977 | Guanmiao Dist., Tainan |

| 12 | Guangji Leiyin Temple | 1986 | Yongkang Dist., Tainan |

| 13 | Sanping Guangji Temple | 1988 | Anping Dist., Tainan |

| 14 | Yongan Bici Temple | 1999 | Yong’an Dist., Kaohsiung |

| 15 | Guidong Sanping Temple | 2013 | Guanmiao Dist., Tainan |

| No. | Temple | Location | Founding Year | Principal Deity | Subsidiary and Attendant Deities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Poh Onn Kong Temple | Malacca | 1781 | Sanping Patriarch | Qingshui Patriarch, Mazu, the Serpent Attendant, the Tiger Attendant, and others |

| 2 | Chiang Chew Association | Malacca | 1936 | Sanping Patriarch | Shakyamuni Buddha, Qingshui Patriarch, Guanyin, and others |

| 3 | Chong Ann Teng Temple | Malacca | 1970 | Sanping Patriarch | Qingshui Patriarch, Guanyin, Mazu, Datuk Gong, and others |

| 4 | Nan Tian Temple (Zu Shi Gong Temple) | Tanjung Sepat, Selangor | 1913 | Sanping Patriarch | the Serpent Attendant, the Tiger Attendant, Guanyin, and others |

| 5 | Matang Hock Chuan Keong Temple | Taiping, Perak | 1895 | Three Loyal Princes of the Song | Sanping Patriarch, Qingshui Patriarch, PuAn Patriarch, and others |

| 6 | Aulong Hock Lok Keng Temple | Taiping, Perak | 1929 | Qingshui Patriarch | Sanping Patriarch, GuanDi, Datuk Gong, and others |

| 7 | Aulong Qing Yun Tan Temple | Taiping, Perak | 1986 | Qingshui Patriarch | Sanping Patriarch, SanDai Patriarch, Datuk Gong, and others |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, S. From Mountains and Forests to the Seas: The Maritime Spread of the Sanping Patriarch Belief. Religions 2025, 16, 1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091194

Huang S. From Mountains and Forests to the Seas: The Maritime Spread of the Sanping Patriarch Belief. Religions. 2025; 16(9):1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091194

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Shaosong. 2025. "From Mountains and Forests to the Seas: The Maritime Spread of the Sanping Patriarch Belief" Religions 16, no. 9: 1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091194

APA StyleHuang, S. (2025). From Mountains and Forests to the Seas: The Maritime Spread of the Sanping Patriarch Belief. Religions, 16(9), 1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091194