Abstract

A Sanskrit manuscript of the Prajñāpāramitā or Perfection of Wisdom in eight thousand verses, now in the Cambridge University Library, Add.1643, is one of the most ambitiously designed South Asian manuscripts from the eleventh century, with the highest number of painted panels known among the dated manuscripts from medieval South Asia until 1400 CE. Thanks to the unique occurrence of a caption written next to each painted panel, it is possible to identify most images in this manuscript as representing those of famous pilgrimage sites or auspicious images of specific locales. The iconographic program transforms Add.1643 into a portable device containing famous pilgrimage sites of the Buddhist world known to the makers and users of the manuscript in eleventh-century Nepal. It is one compact colorful package of a book, which can be opened and experienced in its unfolding three-dimensional space, like a virtual or imagined pilgrimage. Building on the recent research focusing on early medieval Buddhist sites across Monsoon Asia and analyzing the representational potentials and ontological values of painting, this essay demonstrates how this early eleventh-century Nepalese manuscript (Add.1643) and its visual program document and remember the knowledge of maritime travels and the transregional and intraregional activities of people and ideas moving across Monsoon Asia. Despite being made in the Kathmandu Valley with a considerable physical distance from the actual sea routes, the sites remembered in the manuscript open a possibility to connect the dots of human movement beyond the known networks and routes of “world systems”.

1. Introduction

Early medieval travelogues provide useful information about transregional journeys taken by traders, diplomats, spiritual masters, and pilgrims across Asia. Based on the information they provide about each place of their sojourn during their multi-year journeys between India and China, which are often couched as eye-witness accounts, the routes Chinese Buddhist monks like Faxian (journey date: 399–414 CE), Xuanzang (602–664 CE), and Yijing (635–713 CE) took have been mapped.1 While Xuanzang took land routes exclusively for both directions, Faxian traveled by sea on his return journey from India during which he was almost cast away on an island (Sen 2014a, pp. 42–43; Acri 2019b, p. 57), and Yijing took sea routes in both directions, spending a substantial time in the political center coinciding with the modern city of Palembang in Sumatra, which he emphasized as a must stopover for any Chinese monk traveling to India “to listen and read Buddhist laws… to learn how to behave properly” before heading to India (Sen 2014a, p. 50).

Numerous recent studies have emphasized the importance of sea routes and the framework of “Maritime Asia” in understanding pre-modern transcultural activities across Asia (Acri 2016, 2019a; Acri et al. 2017; Sen 2014a, 2014b, 2019, 2023; Ray 2019, 2021; Lee 2021). Along with travelogues, hagiographic accounts of medieval Esoteric Buddhist masters like the Javanese monk Bianhong (Ājñāgarbha) and Dharmakīrti of the Golden Isles have been successfully mined to reveal their hitherto little-acknowledged contributions to transregional and transcultural connectivity across the seas (Sinclair 2019, 2021a; Acri 2019b). In addition to the travelogues and hagiographic accounts of Buddhist masters’ transregional travels, archaeological discoveries of coastal sites and shipwrecks along the coasts of the areas once known as Nusantara also help map these frequently traveled routes that can define the contours of Maritime Asia (Acri 2016, map; Chakravarti 2021; De Saxcé 2022; Guy 2019a, 2019b; Ray 2018). As Ray (2021, p. 5) suggests, it is likely that “coastal architecture provided orientation to sailing ships” when they lacked navigational tools like maps and nautical charts. One could imagine the early eighth-century Shore temple of Mamallapuram (Mahabalipuram) in Tamil Nadu being a great waypoint to set one’s sight on from the sea just as the Nagore Dargah’s soaring minaret towers have provided an important beacon of a haven for seafarers at least since the seventeenth century when the first towering minaret was built.2 Aided by modern technologies, we can map these routes ever more precisely based on architectural and archaeological findings along with textual sources.

How did pre-modern travelers, especially those traveling across Monsoon Asia3 before 1200 CE, develop their itineraries? They certainly did not have a global positioning system. How did the knowledge about these landmarks and places to visit on a long transregional sea journey spread? Could the knowledge of long-distance routes be encoded in Buddhist iconography that circulated across the seas? It would be impossible to retrieve the conversations about and the stories of destinations that must have circulated among the seafarers and travelers of medieval Monsoon Asia. In addition to written and archaeological data, this study advocates for the consideration of Buddhist imagery as a significant source of information. As suggested in recent studies (Kim 2021; Bopearachchi 2022), Buddhist iconography can be parsed for more nuanced historical analysis.4 Here, I argue that we must recognize the power of the images as part of what Ronit Ricci (2011, p. 2) characterizes as “non-inscribed aspects” in “cultural or religious transmission in South and Southeast Asia” to tell us stories of transregional and transcultural travels that are not recorded anywhere else. A painted Buddhist manuscript completed in 1015 CE in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal, contains Buddhist images that we can interpret as recording people’s memories of certain pilgrimage sites and cultic images known at the turn of the eleventh century. By analyzing these images comprehensively, we gain a new window into discerning the contours of these long-lost stories of medieval travels across Monsoon Asia.

Since the seminal publication by the French Indologist, Alfred Foucher (1865–1952) in 1900, the Nepalese manuscript now in the Cambridge University Library, Add.1643, has appeared in several studies, often as an iconographic reference book (i.e., Foucher 1900–1905; Saraswati 1977). Images from this manuscript are frequently cited as examples of a certain Buddhist iconography thanks to the presence of captions accompanying the images, often indicating specific localities, which is rare in the corpus of surviving pre-modern South Asian art. More recent studies have suggested the possibility of reading the manuscript’s overall iconographic program as representing a virtual pilgrimage, with certain choices of images reflecting Nepalese manuscript makers and patrons’ historical awareness of political situations in the South Asian subcontinent (Kim 2013, 2014). Thanks to the Cambridge University Library’s forward-thinking decision to digitize its precious collections, including that of Sanskrit manuscripts, and make them “freely available for use within teaching and research”, which started in 2010, the entire manuscript of Add.1643 including its wooden book covers and all surviving folios are now available for viewing and download on the Cambridge Digital Library’s website.5 By embracing new methodological possibilities of digital humanities and recent and ongoing research on transcultural activities across medieval Monsoon Asia, I propose to use the Add.1643 manuscript’s image program as a guide for mapping an itinerary of transcultural activities that expands our understanding of the connected networks of Monsoon Asia traveled by Esoteric Buddhist masters and pilgrims.

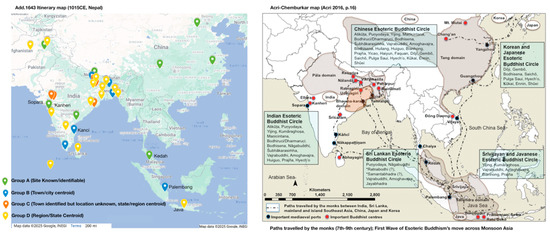

The Buddhist sites that appear in Add.1643 are different from those in earlier travelogues, like Chinese pilgrims’ records: if the British exploration of Buddhism in India had this manuscript as its guide instead of, or in addition to, Chinese pilgrim’s travelogues, we would have had a lot more Buddhist sites excavated in Bengal (West Bengal, India, and Bangladesh) and elsewhere in India.6 We cannot identify every site mentioned in the manuscript with certainty, and the degree of geographic specificity varies considerably (from a shrine to a district, to a mountain, to an island, and to a “country”). However, the map that emerges from the Add.1643 manuscript’s iconographic program can still capture the overall movement of people and ideas across the Buddhist world at the turn of the first millennium (see Appendix A). In fact, the map of the sites that have already been identified in Add.1643 expands the insightful map of the paths traveled by the monks of the seventh and the ninth centuries, connecting various Esoteric circles across Monsoon Asia that Swati Chemburkar and Andrea Acri prepared (Acri 2016, p. 16) geographically and temporally (see Map). It connects the areas missing in the earlier map, namely the Himalayan region, including Nepal, and the sites on the western coast of the subcontinent (Konkan and Gujarat in particular) and further northwest (today’s Pakistan and Afghanistan).7 Once the sites represented in the Add.1643 manuscript are identified fully and geotagged on a digital map, such a map will help define the Second Wave of Esoteric Buddhism’s movement across Asia, which corresponds with the period of phyi-dar, the second or later transmission of Buddhism to Tibet (late tenth through the thirteenth centuries) that certainly inspired many transregional travels by Esoteric Buddhist masters and their disciples and catalyzed numerous translation activities.8

Map.

Left: map of the sites represented in Add.1643 (centroids of four certainty levels), Google My Maps (https://tinyurl.com/MappingADD1643); right: path traveled by the monks (7–9th century) between India, mainland and insular Southeast Asia, China, Japan, and Korea. Map by Swati Chemburkar and Andrea Acri. (Acri 2016).

As one of the first steps towards this goal of using the Add.1643 manuscript as our guide for mapping the visual and material culture of medieval Monsoon Asia, this essay underscores the manuscript’s historical importance, which equally challenges the widely held notions of Nepal’s insularity, peripherality, and even liminality (i.e., being in-between India and Tibet), and presents a few case studies that explore the potential connections between painted images of famous monuments and deities and surviving historical sites. Let us first consider the central object of our query, Add.1643. Despite many previous studies on the manuscript, it is worth spending some moments to learn about its codicological features, overall material and textual structure, and the historical context behind its production.

2. The Manuscript

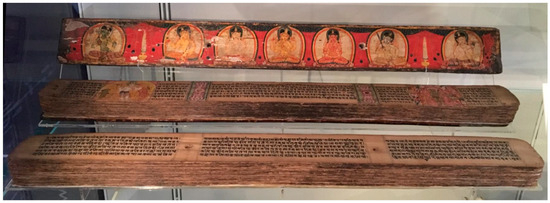

Hailing from the Kathmandu Valley, CUL Add.1643 is a pothi-format palm-leaf manuscript typical of medieval South Asia. The manuscript is made with seasoned palm leaflets cut to a uniform size and held together with a cord or metal sticks (Figure 1). Due to the oblong shape of palm leaflets, palm-leaf manuscripts (and all pothi format books) tend to be horizontally long: this manuscript’s folios measure about 55 cm by 5.5 cm each. There are 223 numbered folios, with 222 palm-leaf folios and one yellow paper folio (folio 1 which is a later replacement). Each folio bears two sets of page numbers on the verso: on the right-hand side are numerals and on the left-hand side are letter numerals.9 These folios are protected by two wooden covers and their exteriors bear signs of being worshipped in the context of pustaka pūjā (worship of book) in Nepal (Kim 2013; Kim 2015).10 It is the manuscript of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā [the Perfection of Wisdom in eight thousand verses, henceforth the AsP]. Like many AsP manuscripts of a similar age, the manuscript starts with a hymn to the Prajñāpāramitā, known as the Prajñāpāramitāstotra of Rāhulabhadra (folios 1v-2r line 1).11 The main text of the AsP ends on folio 222v, with the end of chapter 32 on folio 222r followed by the customary dharma relic beginning with the “ye dharmā…”, which is the verse epitome of the Buddhist teaching, the Pratītyasamutpāda or dependent origination (Boucher 1991; Kim 2013, 2014). The colophon tells us that the manuscript was completed on Thursday, March 3rd, 1015 CE (Nepala Samvat/N.S. 135) in a monastery named Śrī Lham and it was prepared by Sujātabhadra. The monastery’s name has been published as Śrī Hlam repeatedly since Bendall (1883) and Foucher (1900–1905), but the consonant cluster clearly reads “lha” rather than “hla”. While “lha” may not be used in Sanskrit, this is possible in Newari, the language of the Newar people, who are the original inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley to which our manuscript belonged (Kim 2022).12

Figure 1.

A pothi manuscript of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā (AsP), Add.1643, on display at the Cambridge University Library, 29 July 2016. Pigments and ink on palm leaf, 5.5 cm × 55 cm. Photo by author.

According to the colophon, Śrī Lham monastery (“vihāra”) was “the great self-ornament of Nepal [Kathmandu Valley], delight of every being, where the speech of the Buddha shines eternally”.13 We are yet to identify where this vihāra was located in the Valley (possibly in the area near Thamel, Kathmandu) since it is not one of the surviving Buddhist bāhās (Newar Buddhist monastic community-vihāra), some of which claim its illustrious history back to the early medieval period. But this grand statement about its lofty status as a treasure house of Buddhist teaching can be borne out by other known manuscripts prepared in Śrī Lham vihāra.14 One of the earliest known dated Nepalese manuscripts of the AsP (dated 1008 CE), which is also housed in the Cambridge University Library (Add.866), bears the colophon that identifies Śrī Lham vihāra as the site of production (fol. 202v, line 1). Although this is not a fully painted manuscript like Add.1643, it is a precursor to the painted manuscripts like Add.1643 prepared in the same monastery within seven years: there are three large ornamental circles on the recto of the last folio (Figure 2). The designs within these circles vary, but all three are variations on a stylized rendering of a lotus drawn in black ink with strategic application of a red colorant (most likely organic red). They look similar to the lotus-based roundels that appear in ceiling designs of medieval temple architecture (Figure 3).15 A tiny hole in the center of these circles suggests that they were prepared using a tool, most likely a rudimentary compass (Bhattarai 2019, p. 297). An early thirteenth-century manuscript with stunningly painted wooden covers now in the Pritzker collection completed during the reign of Ārimalla I (1200–1216 CE) was also prepared in Śrī Lham, and was identified in the colophon as a Great Monastery, or “Mahāvihāra” (śrī lham śrīmatmahāpratima-mahāvihāre, lit. in the great monastery of an auspicious great image, Śrī Lham) instead of “vihāra” of the eleventh-century colophons, for a monk, Puṣpasena. This suggests that the monastery was a thriving monastic center into the thirteenth century and that the art of painting along with calligraphic skills were deeply cultivated there.16

Figure 2.

Folio 202 with a three roundel design, the AsP manuscript, dated N.S. 128 (1008 CE), Śrī Lham monastery, Kathmandu, Nepal. Cambridge University Library Add.866. Image: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-00866/405. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Figure 3.

Examples of lotus-based roundel-like designs in medieval temple architecture in entrance hall ceiling designs. (left): Khandariya Mahadeva Temple, Khajuraho, c. 1004–35 CE; (center): Lakshmana temple Khajuraho, c. 954 CE; and (right): Medieval Buddhist temple (temple 45) at Sanchi, c. 9th century. Photos by author.

When Foucher first published the Add.1643 manuscript in 1900, he speculated that Śrī Lham must have been a thriving scriptorium to produce multiple copies of a profusely illustrated manuscript based on the internal evidence within the manuscript: there are two folios with identical pagination, folio 120a and folio 120b, and folio120a was later re-paged as folio 109. Folio 109 should bear the end of chapter 11 and relevant painted panels, but instead, this extra folio 120 (120a) is appropriated as folio 109.17 The two folios, 120(a) and 120(b) bear identical text to the extent that folio 120(b) has the last one-third of the sixth line filled with space fillers. Foucher suggested that folio 120(a) may belong to an archetype or “ur” manuscript that others copied. As discussed below, the painting on folio 120(a) is simpler than that of folio 120(b), although two panels in each folio depict identical sites according to the accompanying captions. The physical condition of folio 120(a) is also poorer and unusual in comparison to every other folio of Add.1643 with strips of paper wrapped around the two pseudo columns around the two binding holes.18 It is not clear if 120(a) belonged to an “ur” manuscript but there seems to have been at least one more deluxe copy of the AsP nearly identical to Add.1643, which is now in Tibet (TAR), that awaits further research.19 We will come back to the importance of these two folios.

Another important observation by Foucher is the fact that Add.1643 is a palimpsest because there is a second colophon added in 1139 CE immediately after the first colophon on folio 222v, and the author of the second colophon, scribe Karuṇapurva Vajra, erased the original text that was on folio 223r and wrote his dedication to the Prajñāpāramitā over it (Foucher 1900–1905, p. 20).20 As Foucher observes, the first two stanzas of the Vajradhvajapariṇāmanā (a popular hymn in Tibet) are recopied and squeezed onto the bottom two and a half rows of folio 223r (Figure 4). This text is written in the hand of the second colophon while the remainder of the Vajradhvajapariṇāmanā appears on folio 223v in the script of the main text.21 While it is possible that folio 223r originally contained more than the first two stanzas of Vajradhvajapariṇāmanā, the limited writing space due to the five painted panels on this page—unique to this page in the entire manuscript—suggests that only these verses were initially intended for this folio. Having written his devotional fervor to the Prajñāpāramitā over these stanzas, thus rendering this page a true palimpsest, Karuṇāpūrva Vajra faithfully reproduced them by utilizing the entire available space at the bottom of the page, in a way showing respect for the original scribe, Sujātabhadra.22

Figure 4.

Folios 222v-223r, AsP, 1015 CE (N.S. 135), Śrī Lham monastery, Kathmandu, Nepal. Cambridge University Library. Pigments and ink on palm leaf, 5.5 cm × 55 cm. Post-colophon by Karuṇāpūrva-Vajra in 1139 CE followed by the Vajradhvajapariṇāmanā. Image: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/446 and https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/447. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

3. The Program

Śrī Lham was certainly a leader in painted manuscript production with innovative artists, skillful scribes, and aspiring monastic and lay communities. As noted in previous studies (Kim 2013, 2014, 2021), Add.1643 is the most ambitiously designed manuscript of the eleventh century South Asia, with the highest number of painted panels known among the dated manuscripts: eighty-five painted panels are strewn throughout the manuscript on forty-one painted folios (originally forty-two) out of a total of two-hundred and twenty-three folios.23 Six folios have a single panel placed in the middle of one page (folios 2r, 5v, 8v, 11v, 13v, and 14v, all in chapter 1), thirty-one folios have two panels placed on the right and the left, two folios have three panels (folios 120(b)r, 127r), and two last folios have the most number of painted panels: folio 222 with three panels on each side for a total of six and folio 223r with five painted panels. Each painted folio marks the end and the beginning of each of thirty-two chapters, and the first chapter of the book has six (originally seven) painted folios, all with a single painted panel in the center, and the penultimate chapter (chapter 31) is marked by four painted folios with two painted panels each, placed left and right (folios 216v, 218v, 220v, and 221r). The end of the book and the colophon on folios 222v and 223r are marked by a set of eight major scenes of the Buddha’s biography: three scenes (Birth—Descent from Trayatriṁśa—Monkey’s offering of honey at Vaiśālī) on 222v and five scenes (Taming of a mad elephant—Miracle—Māravijaya—First Sermon—Parinirvāṇa) on folio 223r (see Figure 4). The manuscript’s eighty-five painted panels serve as waypoints in the sea of letters of the Prajñāpāramitā text, giving both an overall physical/visual structure and handy reference points during recitation (see Appendix A for the structure).24

In addition to being profusely garlanded with painted panels, the manuscript provides a rare compendium of specific, localized pictorial representations of existing sites of cultic importance whose specificities are identified in accompanying captions. Visual and textual references to existing places made in the pictorial program of this manuscript are exceptional in the history of South Asian painting, especially for its early date of 1015 CE. Out of eighty-five painted panels, seventy-six panels have captions identifying the painting and almost all captions except for five give location information of the site or image represented in the accompanying painting. Identifying and mapping every site mentioned in the manuscript is part of an ongoing collaborative research project and is beyond the scope of this study.25 Here, I offer some general observations about the quality of the geographic information for future research and the relationship between the text and the image that underscores the painted images’ potential to tell untold stories.

Let us first consider the quality of the location information in these captions from the perspective of using it as geo-data for mapping these sites on a cartographic map. We can identify at least five levels of specificity in geographic information in the image captions (see Appendix A): (A) exact site location with geo-coordinates possible (i.e., painting can be mapped onto a known archaeological site or pilgrimage site, like the Shahji-ki-dheri site of Kaniṣka stūpa near Peshawar, Pakistan) [colored green]; (B) town/city-level identification possible (i.e., painting can be mapped onto a city/town-level centroid, mathematical center of an area, like Tārā of Candradvīpa, near Barisal district, Bangladesh, and Vasudhārā in Kanci in Tamil Nadu) [colored blue]; (C) town/city-level information is available but cannot be mapped beyond region/state level due to the current state of knowledge about ancient toponyms (i.e., Kurukulā on Kurukulā peak in the ancient region of Laṭa-southern Gujarat) [colored orange]; (D) region/state level identification possible (i.e., painting can be mapped with a centroid at the level of a state or an ancient region such as Magadha, Samaṭata, Varendra, and Koṅkan) [colored yellow]; and (E) cosmological locations (excluded from mapping) [colored purple].26 These characteristics are color-coded in Appendix A, which charts the iconographic program with the readings of captions in parentheses and suggests identification of the sites whenever possible with the current state of knowledge on toponyms (also see this map https://tinyurl.com/MappingADD1643).27 As seen in Table 1, a total of sixty-six entries are locatable at the state/ancient region level (a combination of A–B–C–D). As expected, almost half (28 entries) are in eastern India (Bihar, Odisha, West Bengal, and Bangladesh) (see Table 2).28 Fifteen out of the seventy-six captioned images may be identified somewhat reasonably with known archaeological and pilgrimage sites [colored green] (Furui 2023). These images offer a fascinating lens through which we can explore the complex relationship between the paintings and their purported real-world counterparts. Just as the captions exhibit varying degrees of geographic specificity, so do the painted images, but they do not always correspond; highly detailed captions may accompany less specific images or vice versa, suggesting differing levels of familiarity with and knowledge about the sites.

Table 1.

Add.1643 Geodata specificity level.

Table 2.

Geographic distribution outside Eastern India (Bihar, West Bengal, Odisha, India; Bangladesh) in Add.1643 geo information.

The question of why Sujātabhadra and his colleagues in Nepal decided to portray these famous Buddhist sites and powerful devotional images of the Buddhist world known to them in a manuscript of the AsP has been explored in previous studies (Kim 2013, 2014; Granoff 2018). As Kim (2014, pp. 46–47) suggests, the choice of “including numerous regional sites and cult images of specific localities” should be “understood in the context of the pan-Indic phenomenon of regional cult sites becoming transregionally meaningful…the Cambridge manuscript [Add.1643] may represent a pilgrimage cycle of a local Newari Buddhist tradition, which may have developed in response to this larger historical trend of mapping the local sites and making them transregionally meaningful” in medieval South Asia.29 What concerns us here is how they did this, that is, how they managed to represent all of these sites and images pictorially. This gets to the central questions of the essay: how did Sujātabhadra and his colleagues at Śrī Lham monastery in the Kathmandu Valley know about the faraway sites, especially as far as the Malay peninsula, Sumatra, Java, and China; further, how did they know what they looked like?

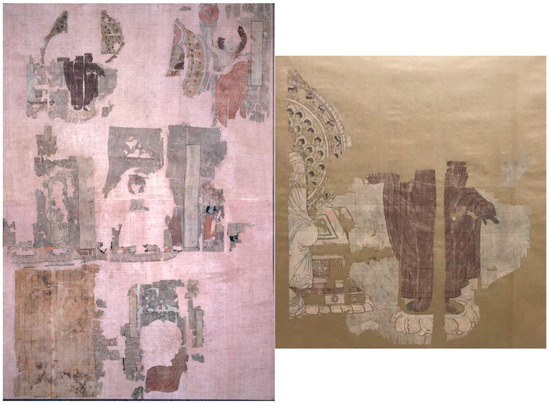

4. Transporting Visions

One of the main arguments in Kim (2021) is that the art of the book in medieval South Asia developed to serve the changing needs of medieval Indic religious communities like Buddhists and Jains. For Buddhists, the need to transmit and circulate images capturing visions of Esoteric Buddhist practices securely and transregionally was met by the technological and artistic breakthroughs in painted palm-leaf manuscripts: a pothi manuscript with painted panels systematically embedded in them, much like Add.1643, was a mobile information device that can carry visual information in a compact, portable, discrete package (Kim 2021, pp. 116–17). Even among the painted manuscripts of medieval Indic Buddhism, Add.1643 is exceptional in that this is the earliest surviving example of its kind and that most images represent not Esoteric Buddhist vision practices but existing pilgrimage sites and exoteric cultic images. Outside South Asia, a pictorial compilation of famous Buddhist images survives from about the eighth century in the context of the transregional and trans-cultural movement of Buddhism across Asia: the paintings of Ruixiang or auspicious images on silk found in Dunhuang’s Library Cave 17, which are now dispersed between New Delhi and London is a great example (Figure 5). The impulse to record the auspicious power sites visually may have been percolating in medieval South Asia (Granoff 2018), but most known examples date after Add.1643.30 Luckily, the internal evidence of Add.1643, the accidental duplicate folios of 120(a) (now appropriated as 109) and 120(b) helps us consider how Sujātabhadra and his colleagues at Śrī Lham may have approached this mighty task.

Figure 5.

Famous auspicious images (Ruixiang): fragmented details from silk paintings from Dunhuang’s Library Cave 17, Tang dynasty, ca. 8th century. British Museum 1919,0101,0.51.1–7, detail on the right: 1919,0101,0.51.4. © The Trustees of the British Museum Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

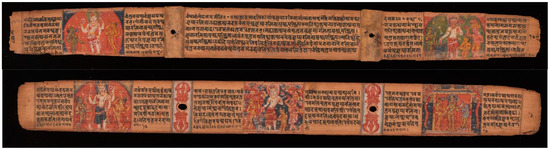

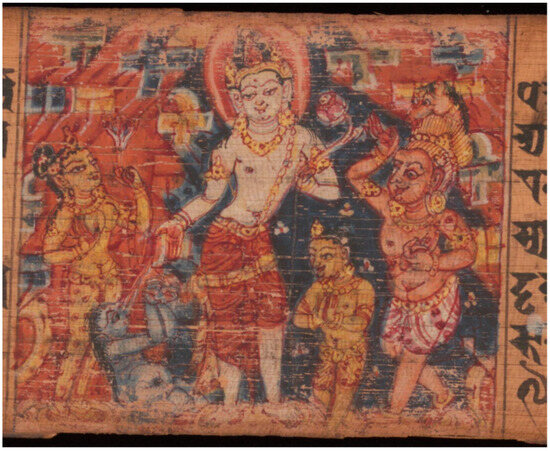

As mentioned above, both folios 120(a)/109 and 120(b) bear identical text. The layout of the two folios differs as folio 120(a) has two painted panels placed on the left and right, whereas folio 120(b) has three panels (Figure 6).31 The caption for the left panel of folio 120(a) is partly missing due to the damage to the folio but we can reconstruct the missing parts of the text based on the caption of the left panel of folio 120(b): dakṣiṇāpathe mūlavāsa lokanāthaḥ, meaning Mūlavāsa Avalokiteśvara in South India.32 The use of more general “dakṣiṇāpatha” or the southern region and the non-specificity of the image in both cases—both depict a four-armed standing Avalokiteśvara, with green Tārā holding an utpāla and four-armed yellow Bṛkuṭī against a red backdrop—suggest that the team’s knowledge of this place and the image was generic (Figure 7 and Figure 8). If anything, the painter of folio 120(a) was a bit more specific about the main deity’s iconography: Avalokiteśvara’s crown is marked with red Amitābha Buddha and his raised right hand holds a rosary, whereas the painter of folio 120(b) omitted these details. Another main difference is the color of Avalokiteśvara’s dhoti where Folio 120(a) shows a translucent and patterned garment (leaving it mostly white) with an orange sash, whereas folio 120(b)’s artist chose blue for the same dhoti.33 The second panel of each folio, right on folio 120(a) and center on folio 120(b), bears identical captions which read “kahṭāhadvīpevalavatīparvatalokanāthaḥ (lit. Lokanātha [Avalokiteśvara] of Valavatī Mountain in Kahṭāhadvīpa”).34 Both paintings depict the same subject, Avalokiteśvara standing in the center holding his right hand lowered in varadā with a Sūcīmukha (lit. needle-faced, hungry ghost) at his right foot receiving direct blessing/nectar from the bodhisattva and accompanied by three other figures: one female and two male (Figure 9 and Figure 10). But how the two artists (let us call them, NAA, Newar Artist A, and NAB, Newar Artist B) executed the scene, even the mood among the figures, and their treatment of the setting/backdrop, differ completely.

Figure 6.

Folios 120(a)/109 and 120(b), AsP, 1015 CE (N.S. 135), ŚrīLham monastery, Kathmandu, Nepal. Cambridge University Library, Add.1643. Pigments and ink on palm leaf, 5.5 cm × 55 cm. Image: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/220 and https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/241. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Figure 7.

“Mūlavāsa Avalokiteśvara in South India” fol. 120(a)/109, left panel, Add.1643. Detail of Figure 6 top. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Figure 8.

“Mūlavāsa Avalokiteśvara in South India” fol. 120(b), right panel, Add.1643. Detail of Figure 6 bottom. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Figure 9.

“Avalokiteśvara of Valavatī Mountain in Kahṭāhadvīpa (Kedah)”, fol. 120(a)/109, right panel, Add.1643. Detail of Figure 6 top. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Figure 10.

“Avalokiteśvara of Valavatī Mountain in Kahṭāhadvīpa (Kedah)”, fol. 120(b), center panel, Add.1643. Detail of Figure 6 bottom. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

NAA sets the pentad against a large green mandorla strewn with a triple-peaked motif (often used to indicate emission of light or heat around a deity) with an orange backdrop where flowers float, mirroring the panel on the left, where Avalokiteśvara’s triad stands against a large red mandorla with a blue backdrop with floating flowers. NAB sets the pentad against a colorful tapestry of geometric patterns that conventionally represent mountainous landscapes, especially rocky mountains, in South Asian art.35 It seems as if Avalokiteśvara emerges out of a natural concave in between the rocky, mountainous landscape: his immediate background and contour are colored deep blue where small flowers float. Matching this dynamic backdrop, the characters’ expressions are more animated and their mood is more joyful in NAB’s version on folio 120(b): Avalokiteśvara’s smile is expressive (with the deep curve of the mouth almost forming a U) and his upper body’s sway to the left is more pronounced than NAA’s version; Hayagrīva, who holds his right hand above his head in the gesture of greeting, looks up to the bodhisattva happily, and his protruding horse head also looks intently at the bodhisattva, in contrast to NAA’s Hayagrīva, who looks rather serious and intense with his gaze directed towards the kneeling Sūcīmukha. The treatment of eyebrows in particular marks the difference: NAA added an extra squiggly line on Hayagrīva’s forehead, making his eyebrows also more zigzagged and upwards, which is typical of the krodha or wrathful deities; the short male figure who folds his hands reverently together in añjalī mudrā (perhaps Sudhanakumāra) also look upwards with a smile; even the hungry ghost is more congenially rendered with a wide eye and a sinuous eyebrow on his profile. The standing female figure holding a water lily depicts Tārā but NAB departed from the convention of painting Tārā green, which NAA followed, and chose yellow instead, enhancing her human-like appearance. While NAA depicted Tārā’s right hand as holding a vitarka mudrā, NAB chose a simpler abhaya mudrā. Why such different approaches to representing the same site and images?

We should not expect these medieval Newar paintings to represent existing sites verisimilarly. But as a thought experiment, let us ask which one is closer to “reality”, not in our modern sense but in the sense of capturing the essence of a place.36 You will agree that NAB (folio 120b) does a better job of capturing the essence of the site, according to the caption, on a mountain on a faraway island. What happened between the two renditions? It seems that they were immediate contemporaries of each other. Yet NAB seems to have had access to more information about the place, which may be identified with Gunung Jerai (Mountain Jerai) in Kedah, Malaysia (Sinclair 2021a; Murphy 2018). Is it possible that someone who came back from a long-distance trip to the Malacca strait told what they had seen as NAB prepared to work on his folio? Or did NAB decide to give it a try where NAA stayed more conservative about this distant place? The ancient region of Nusantara (the Malay peninsula and Indonesian archipelago) where the Śrīvijaya dynasty was powerful until their defeat by the Cōḻa King Rājendra in 1025 CE may seem too far from Nepal geographically to claim any direct interconnectivity. Yet recent studies suggest that this land-locked region of Nepal maṇḍala (the Kathmandu Valley) was very much plugged into the web of transregional travels by seafaring Esoteric Buddhist masters (Sinclair 2018, 2021a, 2021b).

When the famed Indian Buddhist master Atīśa Dīpaṅkaraśrījñāna (986–1054) set out on a sea journey to study with an exceptional Buddhist teacher of the time, Dharmakīrti of the Golden Isles or Suvarṇadvīpa (traditionally believed to be Sumatra), he sailed on a “Nepalese ship”, which elsewhere is identified as a merchant’s ship according to a Tibetan biography of Atīśa recounted in first person (Decleer 1995). Sinclair suggests that this journey to “the Srivijaya and Kedah region” was completed “shortly before Sujātabhadra’s manuscript was completed” (Sinclair 2021a, p. 8). For our purpose, whether Sujātabhadra and his colleagues had access to the first-hand report of this “Valavatī mountain” from Atīśa’s team or not does not matter as much. The point of this exercise is to recognize that such stories of transregional travels circulating orally must have informed the manuscript makers about what these sites and places that they knew only as names in a list of places looked like.37

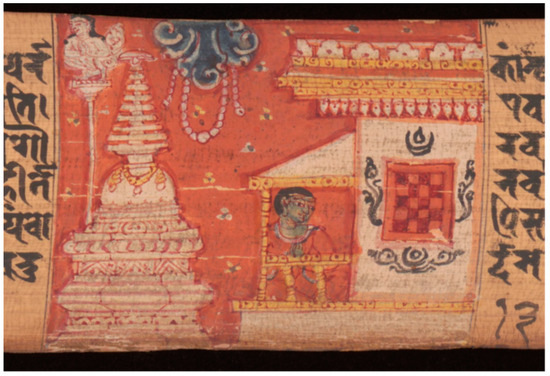

In certain cases, the captions seem to provide a seed for a recall, and the artists knew much more about the places. For instance, the “Dharmarājikacaitya of Rādya” mentioned in the caption of folio 147r (right panel) could have been illustrated through a single stūpa in the center like the Kanakacaitya in Puruṣapūra maṇḍala (Shahjiki-dheri, Kaniṣka stūpa near Peshawar, Pakistan) or any other caityas that appear in the manuscript (Figure 11 and Figure 12). Instead, the painting allocates only about 1/3 of the space to an ornate white stūpa with an adjacent pillar (like an Aśokan pillar) topped by a Garuḍa or kinnara capital. More than half of the space is allocated to a flat-roofed one-story building with a roofed balcony where a monk is seated with his hands in añjalī mudrā facing towards the interior of the building, suggesting a lecture hall or a Buddha hall (Figure 13).38 It seems that the painters knew about the site as a stupa site with an Aśokan pillar and a monastery that surrounds it.

Figure 11.

Kanaka caitya in Puruṣapūra maṇḍala (Kanishka stūpa, Peshawar), fol. 123v, left, Add.1643. Image: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/248. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Figure 12.

Stūpa sites in Add.1643. Left: fol. 202r, left panel, Kurma stūpa in Odisha; right: fol. 218v, right panel, Śrī-Dhānya caitya in Ambu (Amaravati?). Image: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/406 and https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/438. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Figure 13.

Dharmarajika caitya in Radya, Bihar, fol. 127r, right panel, Add.1643. Image: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/255. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

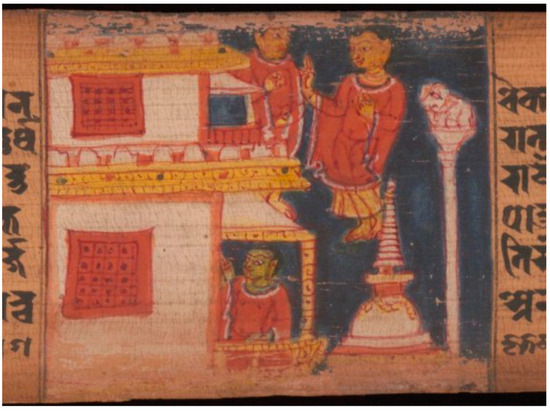

Another monastery, in fact, the sole “vihāra” named among captioned entries, “Candrana (sic) vihāra” in “Supācanagara”, on folio 216v is believed to represent the site of the famed sandalwood monastery in Sopara in coastal Maharashtra where Aśokan pillar and archaeological remains of a Buddhist monastic center are found (Foucher 1900–1905; Brancaccio 2023a). Recent studies by Pia Brancaccio (2023a, 2023b) demonstrate that Sopara was an important port during the first millennium, and the far-reaching fame of this “Candana vihāra” is attested in a seventh-century inscription discovered at the famous site of OC Eo in Southern Vietnam (Chhom et al. 2025).39 The painting shows an impressive two-storied building with lattice windows, which occupies almost two-thirds of the panel (Figure 14). Again, there is a monk on the covered balcony looking into the building with his right hand raised in the gesture of greeting. There is a simple stūpa to the right of the page next to which is an Aśokan pillar. Again, this is most likely a pictorial interpretation of what they have heard about this wealthy monastery rather than what it looked like at the turn of the eleventh century; it is probably based on the general understanding of what a Buddhist monastery in the Gangetic plain looked like, i.e., flat-roofed with short eaves and latticed windows, given the frequent travels by pilgrims, traders, and Buddhist teachers between the Kathmandu Valley and the Buddhist sites in the Gangetic plain. Between the stūpa and the monastery, two monastic figures float in mid-air; their lively interaction is whimsically observed by the elephant on top of the Ashokan pillar—a scene that may reference a particular story about the Candana vihāra.40

Figure 14.

Candana (candrana) vihāra in Sopara (supācanagara), Maharashtra, fol. 216v, right panel, Add.1643. Image: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/434. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Some paintings of unidentified sites in Add.1643 may hold keys to telling untold stories about now-lost Buddhist or even non-Buddhist sites. The strange representation of a floating chatra (umbrella) above a bejeweled stūpa on folio 169r (left panel) may be a literal translation of the name given in the caption, alaga cchatra caitya or “stūpa of a separate umbrella” in Odisha (Figure 15).41 The semi-curved shape of the space within which this stūpa sits with a monk paying homage to it is reminiscent of sectional views of rock-cut caitya halls, like those at Ajanta in Maharashtra. We also recall a story reported by Xuanzang about a Buddha image at Ajanta on top of which stone canopies marvelously hovered over it without any support. I am not suggesting that this image represents one of Ajanta’s caitya halls (Figure 16). Rather, I would like to entertain the possibility that this image carries a vestige of distant memories of marvelous places translated into a painting of a single Buddhist site in Odisha. These memories could include the story of floating canopies of Ajanta reported by Xuanzang; it could also (mis)remember and translate a story about an impressive Hindu temple with a levitating idol or pillar in Odisha.42 My speculations about lost stories are thought experiments but they demonstrate how taking the images seriously in their own historical context and imagining the process of making and their potential inspirations can provide clues about what to look for in surviving—and yet-to-be-discovered historical—records.43

Figure 15.

Alagachatra [detached canopy/umbrella] caitya in Odisha, 169r, left panel, Add.1643. Image: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/339. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

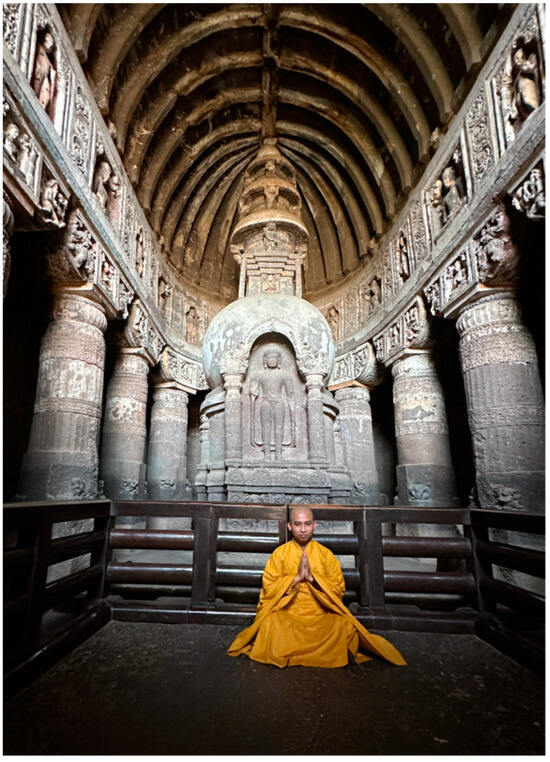

Figure 16.

View of the stūpa with a Buddhist monk in a caitya hall, Cave 19, Ajanta, Maharashtra, c. fifth-century CE. 8 March 2024. Photo by author.

5. Buddha in the Great Ocean

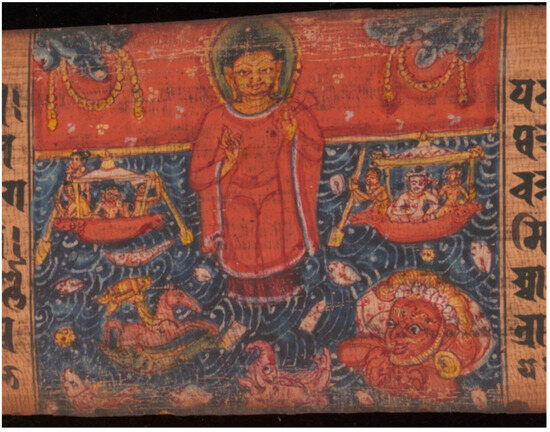

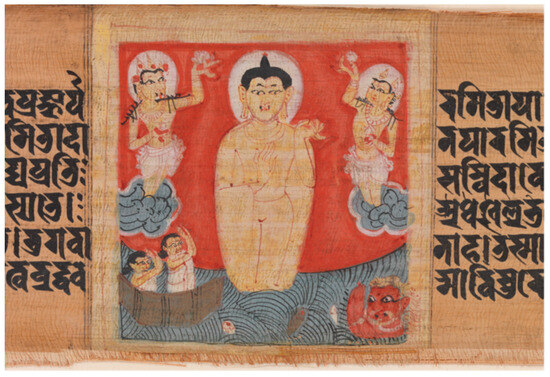

In the context of maritime travel and connectivity across Monsoon Asia, the left panel on folio 20v in Add.1643 presents the most captivating and pertinent image (Figure 17). The painting depicts a standing Buddha holding his right hand in abhaya (fear-not; reassurance) mudrā, floating in the middle of the ocean. Two small boats that look rather unfit for an ocean-going voyage float on either side with each oarsman busy anchoring their boat. Undulating white lines in circular repetitions against deep blue represent a turbulent sea. Sea creatures, fish, sea snails, a makara (mythical aquatic animal associated with controlling water), and an unusual combination of a golden turtle above a red horse above another makara-like creature, add to the dynamism of the scene through their curved shapes and fluid lines. The antagonist, or in this case, the subdued, is the red demonic figure on the bottom right, which is only visible from the shoulder up with his hands cupped right under the chin in a gesture described as ādhāra mudrā (holding water gesture) (Markel 1990, p. 11). This figure is Rāhu, the eighth of the nine planetary deities or Navagraha known as the demon causing eclipses. The sky looks largely clear of the storm and the garlands hanging from two dark clouds celebrate the miracle of quelling the raging sea that the Buddha performs. The caption of the image reads Abhayapāṇi (lit. the one with the abhaya gesture) quelling Rāhu in the Great Ocean (mahāsamudre rāhukṛta abhayapāṇi).

Figure 17.

Buddha (Abhayapāṇi) subduing Rāhu in the Great Ocean, fol. 20v, left panel. Add.1643. Image: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/42. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Phyllis Granoff (2018, pp. 22–23) suggested that this scene may depict the stories known from the Samyutta nikāya about Rāhu going after the sun and moon out of jealousy and the Buddha subduing him. According to the Candimasutta and Sūryasutta, “the gods of the sun and moon palace call upon the Buddha for help and the Buddha orders Rāhu to release them on pain of death” (Granoff 2018, p. 23). It is possible that these old stories about Rāhu were known to Sujātabhadra and his colleagues at Śrī Lham. The two small boats that look more like coastal pleasure boats rather than ocean-going ships may represent the “lunar and solar palaces, or vimānas” as Granoff suggests (Granoff 2018, p. 22). Although plausible, this old story’s relevance for the Newar Buddhist community of the early eleventh century is yet to be established. Relying only on textual sources also misses the opportunity to see the historical significance of this scene and the manuscript at large. If we listen to the painting more closely and consider other contemporary and near-contemporary historical and art historical evidence, there are more immediate stories that the painting likely recalls.

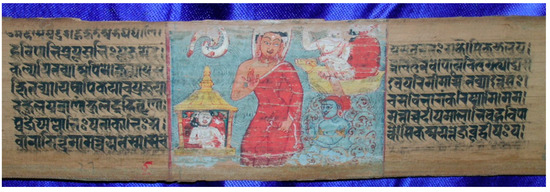

First, it is important to remember that Add.1643 inspired what I would call mediated replicas akin to two- or three-generation-removed kin, as noted in Kim (2014). One of them is the AsP manuscript in the Asiatic Society, Kolkata, A.15, which was discussed together with Add.1643 by Foucher (1900–1905). This manuscript, prepared in 1071 CE (N.S. 191), is more streamlined in its design and has only thirty-six painted panels. The same scene of subduing Rāhu appears with the exact same caption, this time on folio 34r marking the end of chapter 3 (Figure 18). Here, the ocean is lighter blue with swirly undulating lines in thin wiry strokes. The scene is more simplified than in Add.1643 as the standing Buddha occupies the whole height of the panel dominating the scene and there are only two fish as token aquatic creatures. Instead of two small pleasure boats, we see one yellow boat on the upper right and a pavilion on the lower left. That the boat was under disturbance is indicated by wiry black lines of waves that intrude onto the boat’s port-side hull. Under the boat is again the sea demon figure, rising out of the swirling wavy patterns drawn in red. This time, he pays homage to the Buddha with his hands folded in front of him instead of in the ādhāra mudrā typical of Rāhu. If the two small pleasure boats in Add.1643 may have invoked a vimāna in shape, here there is no question about it being a merchant’s boat: the giant red jar being transported on the boat in the upper right is expected in the yellow pavilion in the lower left, where a man sits in front of another two giant red jars.

Figure 18.

Buddha (Abhayapāṇi) subduing Rāhu in the Great Ocean, fol. 34r, center. AsP, 1071 CE (N.S. 191), Kathmandu, Nepal. Asiatic Society, Kolkata, A.15. Photo by author.

Buddha protecting merchants is an expected condition of Buddhism’s spread across Monsoon Asia. Newar merchants of the Kathmandu Valley have played a prominent role in transregional trade, especially in the “trans-Himalayan Buddhist trade network”. (Lewis 1993, p. 145; 2023). Although imagining an ocean-going merchant group from this land-locked region seems like a challenge, Atīśa’s Tibetan biographers clearly mention that he was on a Newar mercantile ship.44 In a way, the rendition of a merchant’s boat in A.15 enhances our understanding of the context of the scene in Add.1643 and its connection to Atīśa’s sea voyage. The scene of the Buddha quelling Rāhu in the Great Ocean in Add.1643 recalls the torrential storm and obstruction of the passage by the “great makara sea monster” that Atīśa faced on his way to the Golden Island to meet his teacher (Decleer 1995, p. 412).

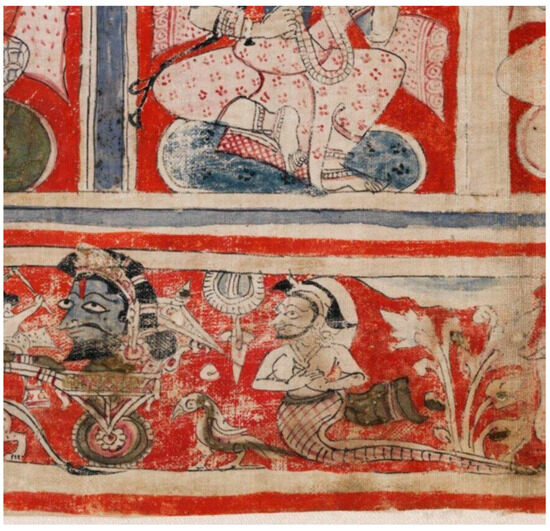

A host of protective deities are called upon to deal with the treacherous situation. In response to the plea of his disciple, Kṣitigarbha, Atīśa himself takes the form of Raktayamāri, or Red Slayer of Death: “Then I [turned into] the Bhagavān Slayer of Death [Yamāri], [my] body red, with a fat belly, dark brown hair waving upward, with reddish eyes wide open looking into the ten directions” (Decleer 1995, p. 414). Raktayamāri’s form described here is a common type of krodha or wrathful deity (lambodāra or pot-bellied type) (Linrothe 1999).45 This description can also apply to the image of Rāhu in Add.1643 who is red with yellow hair waving upward. It is hard to speculate about the color of Rāhu as understood by people in medieval South Asia because most known Rāhu images from medieval South Asia are in sculptures. A detail from a Jain victory yantra (Jayatra yantra) dated 1447 CE shows Rāhu in dark blue color, which goes well with the understanding of Rāhu as an eclipse demon (Figure 19). Given this discrepancy, is it possible that the Atīśa story about Raktayamāri in the ocean was already circulating in the Kathmandu Valley when Sujāta-bhadra took on this project? Rāhu is not colored red in A.15, but the demon appears out of swirly patterns composed in red. Even in the most simplified, concise version of the same scene, appearing in the early twelfth-century manuscript of the Prajñāpāramitā from southern Bengal, another distant kin of Add.1643 as discussed in Kim (2014), the painter also uses red color for Rāhu (Figure 20).

Figure 19.

Detail of Rāhu (colored blue) and Ketu of the Navagrahas in Jayatra yantra, c. 1447 (V.S. 1504), Gujarat. Pigments on cloth. V&A IM 89–1936. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O17102/victory-banner-unknown/?carousel-image=2013GM4572.

Figure 20.

Buddha subduing Rāhu in the Great Ocean, fol. 402v, PvP Ms, c. 1100 CE (Harivarman 8th year), southeastern Bengal. Pigments and ink on palm leaf. Painted panel: 5.6 cm × 5.8 cm, folio size: 56.6 cm × 5.8 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 52.93.1. Image: www.metmuseum.org, Open Access Public Domain.

In fact, this painting in the dispersed manuscript from southern Bengal helps us see something else: the colossal scale of the Buddha appearing in the middle of the sea. In comparison to the same scenes we examined in Add.1643 and A.15, the painting is notable for its visual economy and efficiency. The Buddha’s body is outlined with single reddish-brown lines so light and rhythmic that one can discern where the artist halted his tiny brush. Black ink is economically used to draw eyes, hair, floating clouds, and undulating lines of ocean water. The cursory and casual nature of these black lines adds to the liveliness of the scene. Some lines appear almost clumsy, and abbreviation and swift execution seem to have been the artist(s)’s forte. The lack of draftsmanship, however, did not compromise the iconographic clarity or the power of the Buddha subduing “Rāhu” in the Great Ocean. The sky, again depicted in red as in Add.1643, is given more than three-quarters of the space against which the Buddha’s standing body glows. The two ceremonial boats in Add.1643 are changed to a single plain paneled wooden boat, probably the kind of boat used in the coastal region of Bengal. Two figures simply dressed in white (not the devas of solar and lunar palaces) stand in the boat. They look up and pay homage to the Buddha for his safely delivering them from a raging storm. Aquatic creatures are simplified to three fish popping in between the waves. Despite its simplicity, certain details help tell a more exuberant story, like the celestial beings that are coming out of the clouds and about to offer flowers to the Buddha. Their prominent position and the compositional scale change, i.e., the Buddha’s dominance in the open red sky tell the story of a marvelous happening at sea: a raging storm suddenly calms, and the sun breaks through the clouds. We see the sense of relief and gratitude of the people in the boat as soothing winds that feel like celestial music replace the storm’s roar and as the dark clouds make the sun’s radiance even more striking, all of which is conveyed here by these celestial beings. Here, if we look back at the panel in Add.1643 with this later version in mind, the dark clouds with hanging garlands and the flower-strewn red sky now make a more dramatic impression of the story.

Tumultuous storms in the middle of the ocean feature frequently in Buddhist narratives from early on (i.e., Mahājānaka jātaka, Siṁhala avadāna). The perils at sea are a common ingredient in the biographies of Buddhist masters traveling across the “maritime trading channels” across Monsoon Asia (Acri 2019b). Acri observes that this trend is not just based on an imaginary scene but also on actual experience, which “testifies to the increasing popularity of maritime travel in Buddhist communities from the sixth century onwards”. This is also seen in the “concurrent development in the same locales of ‘saviour cults’ focusing on the Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, Tārā (especially in her aṣṭmahābhaya aspect) and Mahāpratisarā as protectors of travellers, and of sailors in particular” (Acri 2019b, p. 53). Interestingly, however, none of the known maritime travel accounts of Buddhist masters feature the Buddha himself appearing at sea as the savior. Atīśa’s travelogue expands the pantheon of wayfaring guardians to include the deities of the so-called “higher” Tantras, like Raktayamāri, Yamāntaka, and Krodharāja Acala, but the Buddha does not appear as the action hero. This is where it is important to consider the context of the manuscript’s program as recording an ambitious itinerary traversing the vast Buddhist world known to those in the Śrī Lham monastery in Nepal at the turn of the eleventh century.

Let us consider another hypothetical scenario. What if the iconography of the Buddha subduing Rāhu in the Great Ocean remembers a story of a monumental rock-cut Buddha on an island serving as a beacon for seafarers? Pia Brancaccio (2020, p. 178) draws our attention to one such story about a colossal Buddha image with miraculous powers in the Indian Ocean. According to Xuanzang, “Crossing the sea westward from this island [Sri Lanka] several thousands of li, on the eastern cliff of a solitary island is a stone figure of Buddha more than 100 feet high. It is sitting facing the east” (Beal 1906, p. 252). This colossal Buddha hewn out of rock saved a group of merchants stranded after a storm by providing fresh water from the gem fixed uṣṇīṣa. We may not be able to identify the exact monumental rock-cut Buddha on an island as described by Xuanzang although Samuel Beal’s suggestion of the Maldives may be possible (Beal 1906, p. 252, fn. 26). No substantial art historical or in-depth archaeological scholarship exists on the Buddhist past of the Maldives, but it is clear from existing studies (Gippert 2004, 2013) that Buddhism was active in these islands until the turn of 1100 CE, thus making cultic sites in the Maldives coeval with our manuscripts. Jost Gippert (2004, 2013) provides a comprehensive analysis of epigraphic evidence in Prakrit and Sanskrit written in Southern Brāhmī/Grantha-based script found in the Maldives. Gippert (2013) identified the Yamāntaka mantra inscribed directly on two coral stone sculptures, each with six wrathful faces carved all around, bearing “clear witness to Tantric Buddhism prevailing on the Maldives before the introduction of Islamic faith” in the twelfth century (p. 134). The type of the texts identified by Gippert (i.e., Sitātapatrā dhāraṇī and Yamāntaka mantra) suggests the largely talismanic role of these inscriptions associated with averting perils, which must have been particularly important for seafarers seeking landfall: this island archipelago was a divine harbor refuge five hundred miles west from India and Sri Lanka in the Indian Ocean.46

With little surviving evidence, it is difficult to know what such a colossal sculpture of the Buddha may have looked like if a colossal rock-cut sculpture ever existed on one of the islands in the Maldives.47 Brancaccio’s insightful study of colossal rock-cut Buddhas of Sri Lanka helps us imagine what the Buddha remembered in the iconography of the Buddha offering protection in the Great Ocean would have looked like: in the landscape, with seasonal flows of water around the Buddha, “visually evoking the miraculous scenario” (Brancaccio 2020, p. 179). Coincidentally, all the monumental rock-cut Buddha sculptures of Sri Lanka have the right hand raised in abhaya mudrā or its variation (hand-held sideways) and hold the end of the garments in raised left hand as we see in Add.1643.48 Colossal Buddha statues stand as landmarks across the Silk Road, on both maritime and land routes (Brancaccio 2020; Wong and Heldt 2014). They are located often near a body of water, as observed in Sri Lanka (Brancaccio 2020) and elsewhere, suggesting their function in offering protection.49 Thus, despite their absence in Buddhist travelogues, in practice, the colossal Buddha statues must have remained important reference points in discussing itineraries for maritime journeys. At least for the manuscript makers in Nepal, standing Buddhas offering protection, i.e., holding abhaya mudrā, and on islands, were important in charting the ocean-crossing itinerary, as seen in the images of Dīpaṅkara Buddhas, one in the island of Java (fol. 2r) and another one in Sri Lanka (fol. 8v) in Add.1643.50

Finally, the centrality of this Great Ocean Buddha scene in the manuscript’s design is also confirmed in its strategic placement in the overall layout of Add.1643. The layout of each painted page changes from one painted panel per folio to two per folio from this page. The previously painted folio in the program, folio 14r, features a single painted panel: a painting of Avalokiteśvara of the uniquely Nepalese site, “Svayambhū” (nepāle svayambhū lokanātha), which is paired with the panel depicting the goddess Prajñāpāramitā on the Vulture Peak (gṛḍhrakūṭaparvate prajñāpāramitā) on folio 13v. It is as if the Great Ocean Buddha panel announces the long-distance journey that unfolds in the manuscript over which the Buddha provides protection. This sense of marking the beginning of a sequence in the manuscript’s design is amplified in A.15, where every painted folio has a single painted panel and marks the end of a chapter (and the beginning and the end of the manuscript). The streamlined program makes it easier to identify a pattern in the overarching program. In A.15, our scene appears at the end of chapter 3 on folio 34r and the sites before this point in the program either relate directly to the text (fols.1v, 2r, 12r) or a site in Nepal (fol. 18r). The sequence of Prajñāpāramitā (fol. 12r) and the uniquely Nepalese Avalokiteśvara, this time identified as “Buṅgama Lokeśvara in Nepal” (fol. 18r), is the same as in Add.1643, except that now each marks a chapter ending instead of facing each other at the end of one chapter.51 In addition, A.15 relegates the two Dipaṅkara Buddhas, one in Sri Lanka and one in Java, much later than the Great Ocean scene, on folio 72r and fol. 83r, respectively. This placement ensures all transregional locations appear in the manuscript after the Great Ocean scene.

6. Epilogue

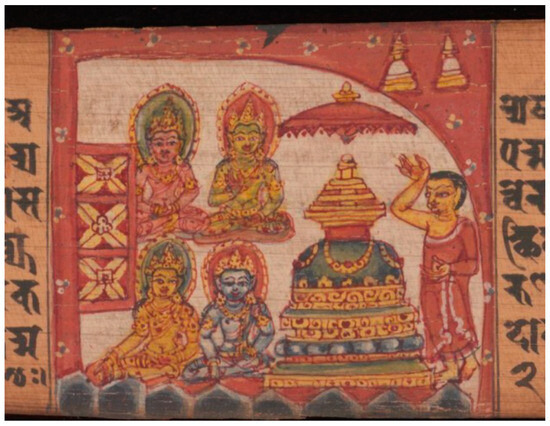

Mapping all the sites associated with Add.1643 with geo-coordinates is an impossible task with our current state of knowledge on pre-modern toponyms. Yet as we have seen, concerted efforts to unpack potentially embedded stories from the painted images can present a promising path to look for more clues and lesser-explored historical records. We discussed some images that relate to maritime travels in Add.1643 but there are many more: in Sri Lanka, for instance, we find Jambhala in the rocky setting (fol. 80v right) and healing hall Avalokiteśvara (fol. 86r right) in addition to Dīpaṅkara. All three are located in “siṁhaladvīpa” according to the captions, which may be mapped at level D, with a centroid for Sri Lanka (7°52′37.5″ N 80°41′52.5″ E). Identifying specific sites will require further research in each region. The painting of Jambhala appears more specific with a rocky and jewel-like landscape as the backdrop while the “healing hall” Avalokiteśvara (ārogaśālālokanātha) appears rather generic despite the specificity in the name (Figure 21 and Figure 22). The bodhisattva’s epithet “healing hall” in fact recalls a story of a Buddhist master, Candragomin, who traveled to Sri Lanka and eliminated leprosy by building a temple to Avalokiteśvara according to the sixteenth-century author Tāranātha’s History of Indian Buddhism (Chimpa and Chattopadhyaya 1970, p. 202). This account is preceded by the origin story of Candradvīpa: an island magically appeared at the mouth of the Gaṅgā river where it meets the sea in response to Candragomin’s prayer to Tārā when he was thrown into the water. Candragomin builds a shrine to Tārā and Avalokiteśvara on this island from where in the biography he seems to have proceeded to Sri Lanka. Is it a pure coincidence that the painted panel depicting Tārā in Candradvīpa is placed on the same page as the Jambhala (in Sri Lanka) panel (both on folio 80v, left and right, respectively) as if recalling the itinerary of Candragomin?

Figure 21.

Jambhala in Sri Lanka, fol. 80v, right panel, Add.1643. Image: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/162. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Figure 22.

Healing Hall Avalokiteśvara in Sri Lanka, fol. 86r, right panel, Add.1643. Image: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/173. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

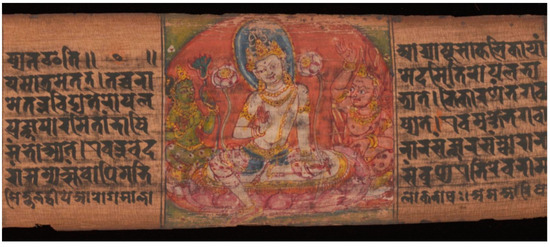

This painting of Tārā of Candradvīpa also happens to be a unique example of evolving pictorial strategies that cleverly indicated that Tārā is on an island at the confluence of rivers and the ocean (Figure 23). Green Tārā sits in the middle with one leg pendant and showing the varadā mudrā in the right hand and a utpala in the left. This is set within a grid like a triptych, and eight squares distributed evenly on either side contain eight miniature images of herself, representing the iconography of Aṣṭamahābhaya Tārā, the goddess Tārā as the savioress from eight great perils.52 This form of Tārā holds paramount importance and widespread appeal among seafarers. Perhaps acknowledging this superpower of Tārā, the artists framed this “triptych” of Tārā with a wide blue border strewn with floating flowers, which may cleverly represent the water on all four sides of the island located at the oceanic entrance, a suitable launch place for transregional sea journeys like the one taken by Candragomin remembered by Tāranātha. How many more stories like this one we will be able to unpack in Add.1643 remains to be seen. This Nepalese manuscript, Add.1643, in fact, holds many ambitious itineraries, each awaiting meticulous exploration and interpretation. While this essay offers a small glimpse, it serves as an invitation to further scholarly inquiry. Further research will help illuminate vast networks of cultural exchange across medieval Monsoon Asia, enhancing our understanding of historical interconnectivity.

Figure 23.

Tārā of Candradvīpa, fol. 80v, right panel, Add.1643. Image: https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-ADD-01643/162. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Funding

This publication has been partly supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR), project MANTRA—Maritime Asian Networks of Buddhist Tantra (ANR-22-CE27-015), coordinated by Andrea Acri (EPHE, PSL University, Paris).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was published in the special issue “Beyond the ‘Spice Routes’: Indic and Sinitic Religions across the Asian Maritime Realm”, with Andrea Acri and Francesco Bianchini serving as guest editors. It is based on a conference paper given at the “Beyond the Spice Route” symposium at King’s College, University of Cambridge, on 7 November 2023, part of the King’s College “Silk Roads Programme” co-funded by the French EPHE, GREI, and ANR. I would like to thank Andrea Acri for sharing the reference to Bandaranayake, 2012, and other works on Monsoon Asia. I thank Todd T. Lewis for reading an early draft of the article and providing references on Newar Buddhism. The presentation of mapping data and research for geo-coordinates was supported by Tracy Stuber (Digital Humanities Specialist, Arts & Humanities Computing at Harvard) and John Weaver (Harvard College 2026). The core idea for this article was developed as part of the author’s Harvard College undergraduate lecture course, HAA81 Art of Monsoon Asia: Interconnected Histories, offered in Fall 2021 and 2023. I thank the students of HAA81 for their insightful questions and enthusiasm.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Iconographic structure color-coded for geo-data specificity level. CUL Add.1643, dated 1015 CE53.

Table A1.

Iconographic structure color-coded for geo-data specificity level. CUL Add.1643, dated 1015 CE53.

| Fol. No. | Painted Panel(s) Placement [Left-Center-Right] | Specificity Level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fol.1v | Yellow Paper Replacement | |||||

| Fol.2r | Dīpaṅkara in Java island [Java] (yavadvīpe dīpaṅkara) | D | ||||

| Fol.5v | Vajrasattva on Mt. Meru (sumerovajrasatvaḥ) | E | ||||

| Fol.8v | Dīpaṅkara in Sinhala island [Sri Lanka] (sinhaladvīpe dīpaṅkara) | D | ||||

| Fol.11v | Lokanātha on Mt. Kapota in Magadha [Bihar] (magadhe kāpotaparvate lokanāthaḥ) | C | ||||

| Fol.13v | Prajñāpāramitā on vulture peak [Rajgir, Bihar] (gṛdhrakūṭaparvate prajñāpāramitā) | A | ||||

| Fol.14r (Ch.1 ends) | Svayambhū-Lokanātha, Nepal [Nepal, Kathmandu valley, Bunga-dyah] (nepāle svayamṁbhūlokanāthaḥ) | A | ||||

| Fol.20v (Ch.2 ends) | Rāhukṛta-Abhayapāṇi in Great ocean (mahāsamudre rāhukṛta-abhayapāṇi), Maldives? | Preaching Buddha in Punḍavardhana [ Mahasthangarh, Bangladesh] (puṇḍavarddhane triśaraṇa-buddhabhaṭṭārakaḥ) | D-B | |||

| Fol.40v (Ch.3 ends) | Macchītivahti-Lokanātha in Magadha [Bihar] (magadhe macchītivahti-lokanāthaḥ) | Maitreya in Tuṣita heaven (tuṣitabhavane maitreya) | D-E | |||

| Fol.44r (Ch.4 ends) | Buddha of Gandhavati [lit. fragrant lord], Kalaṣavarapura (kalaṣavarapure gandhavatyā bhagavān) | Buddha in Trāyatriṁśa heaven (trāyatriṁśe bhagavān) | ?-E | |||

| Fol.59r (Ch.5 ends) | Vardhamāna stūpa of Tulakṣetra [Śrīksetra in Burma? But later it has Varendra attached to Tulākṣetra on folio 174] (tulākṣetra-varddhamāna-stūpaḥ) | Tārā (of forest) in Vārendra [Northern Bangladesh/northeastern W. Bengal] (vārendrā-vāṇā-icchā-mahāttarāyī) | D-D | |||

| Fol.74v (Ch.6 ends) | Preaching Buddha in Yānavyūha [Sarnath?] (yānavyūha-bhagavan) | Tārā in Potalaka (potalake bhagavī-tārā) | ?-B | |||

| Fol.80v (Ch.7 ends) | Tārā in Candradvīpa [SE Bengal] (candradvīpe bhagavatī-tārā) | Jambhala in Sinhala Island [Sri Lanka] (sinhaladvīpe jambalaḥ) | B-D | |||

| Fol. 86r (Ch.8 ends) | Campitalā-Lokanātha in Samataṭa [SE Bengal] (campitalā-lokanāthaḥ samātaṭe) | Ārogyaśālā-Lokanātha in Sinhala island [Sri Lanka] (sinhaladvīpe ārogaśālā-lokanāthaḥ) | D-D | |||

| Fol.89r (Ch.9 ends) | Lokanātha in Mt. Kuṭa in Gandhara [NW Pakistan] (gandhāramaṇḍale kūṭaparvate lokanāthaḥ) | Maṅgakoṣṭa-Vajrapāni in Oddiyana [Swat Valley, Pakistan] (ottiyāna-maṅgakoṣṭa-vajrapāṇi) | C-C | |||

| Fol.99v (Ch.10 ends) | Lokanātha in Śrīvijayapura in Suvarṇṇapura [Palembang, Sumatra?] (suvarṇṇapure śrīvijayapure lokanātha) | Tārā in Tārapur, Laṭadeśa [Broach, S. Gujarat] (lahtadīse tārapure tārā) | B-C | |||

| Fol.120(a)r [109] (Ch.12 ends) | Lokanātha [South India?] ([dakṣiṇāpathe mūl..?] lavāsa-lokanāthaḥ) | Lokanātha in Mt. Valavatī in Kahṭāhadvīpa [modern day Kedah near Penang, Malaysia] kahtāhadvīpe valavatīparvate lokanāthaḥ] | D-A | |||

| Fol.120(b)r (Ch.12 ends) | Mūlavāsa-Lokanātha in South India (dakṣiṇāpathe mūlavāsalokanāthaḥ) | Lokanātha of Mt. Valavatī, Kaṭāhadvīpa [Kedah near Penang, Malaysia] (kahtāhadvīpe valavatīparvata-lokanātha) | Tārā in Kambojadeśa [Afghanistan] (kambojadeśe tārā[ḥ]) | D – A-D | ||

| Fol.123v (Ch.13 ends) | Śrī Kanakacaitya in Peshawar, in the northern country [Shaji-ki-dheri stūpa?, Peshawar, Pakistan] (uttarāpathe puruṣapuramaṇḍale śrīkanakacaityaḥ) | Buddharūpaka-Lokanātha in Mahācīna [Lokanātha in the form of Buddha in China—Dizang] (mahācine buddharūpaka-lokanāthaḥ) | A-A | |||

| Fol.127r (Ch.14 ends) | Samantabhadra in China (mahacīne samantabhadraḥ) | Kanyārāma-Lokanātha in Radya [Radhiya, Bihar] (rādyakanyārāma-lokanāthaḥ) | Dharmarājikā-caitya in Radya [Rādhiya, Bihar] (rādyadharmarājikā-caityaḥ) | A-B-A | ||

| Fol.133r (Ch.15 ends) | Rāmājaṭa-Lokanātha in Rādya [Radhiya, Bihar] (rādyarāmājāhta-lokanāthaḥ) | Lokanātha of Yajñapiṇḍī in Daṇḍabhuktī [N.Odisha] (daṇḍabhuktau yajñapiṇḍī-lokanāthaḥ) | B-D | |||

| Fol.139r (Ch.16 ends) | Vajrāsana Buddha, Lūtū, Rāḍha [W.Bengal] (rāḍhalūtū-vajrāsanaḥ) | Vattavanā-Lokanātha in Rāḍha [W. Bengal] (rāḍhavattavanā-lokanāthaḥ) | D-D | |||

| Fol.147r (Ch.17 ends) | Bhaṭṭāraka-Valiya Lokanātha (bhaṭṭāraka-valiya-lokanāthaḥ) | Thousand-armed Lokanātha in Śivapura, Koṅkan [Shivpur?, Coastal Maharashtra] (koṅkane śivapure sahasrabhujā-lokanāthaḥ) | ?-C | |||

| Fol.151r (Ch.18 ends) | Lokanātha in Śrī-Khairavaṇa, Koṅkan [Coastal Maharashtra] (candraṭura-koṅkaṇe śrīkhairavaṇe lokanāthaḥ) | Lokanātha in Jāruha, Magadha [Bihar] (magadhe jāruhe punnavā-lokanāthaḥ) | C-C | |||

| Fol.157v (Ch.19 ends) | Tārā of Vaiśāli, Tirabhukti [Vaishali, Mithila, Northern Bihar] (tirabhuktau vaiśālī-tārā) | Lokanātha of Candragomin in Nālandā [Nalanda, Bihar] (śrīnālendrāyāṁ candragomiṇa-lokanāthaḥ) | A-A | |||

| Fol.164v (Ch.20 ends) | Vandikoṭo Lokanātha (vandikoṭo-lokanāthaḥ) | Khadiravaṇi-Tārā in Koṅgomaṇḍala [Odisha] (koṅgomaṇḍale khadiravaṇi-tārā) | ?-C | |||

| Fol.169v (Ch.21 ends) | Alagacchattra-Caitya in Odisha (oḍḍadese alagacchattra-caityaḥ) | Tārā in Tārapura, Laṭa [Broach district, S. Gujarat] (lāhtadese tārapure tārāḥ) | D-C | |||

| Fol.174v (Ch.22 ends) | Alagataru-Tārā in Odisha (oḍradese alagataru-tārā) | Lokanātha of Tulākṣetra, Vārendra (vārendrā-tulākṣetra-lokanāthaḥ) | D-D | |||

| Fol.176v (Ch.23 ends) | Cundā in Cundāvarabhavan in Paṭṭikera [Comila district, Bangladesh] (paṭṭikere cundāvarabhavane cundā) | Stūpa of Mṛgasthāpana, in Vārendrā (vārendrā-mṛgasthāpana-stūpaḥ) | C-C | |||

| Fol.179v (Ch.24 ends) | Kurukulā on Kurukulā peak, in Laṭadeśa [Broach, S. Gujarat] (lāhtadese kurukulāśikhare kurukulā) | Vedakoṭo-Lokanātha, Koratra (koratre vedakoṭo-lokanāthaḥ) | C-? | |||

| Fol.184r (Ch.25 ends) | Stone Lokanātha in Harikella [SE Bangladesh] (harikelladese śila-lokanāthaḥ) | Tārā, Varendra (varendrā-mahattarāyī-tārā) | D-D | |||

| Fol.188r (Ch.26 ends) | Lokanātha of Dedapura, Varendra (varendrā-dedapura-lokanātha) | Cundā in Vuṅkarānagara, Laṭa [Broach, S. Gujarat] (lāhtadese vuṁkarānagare cundā) | C-C | |||

| Fol.193r (Ch.27 ends) | Jayatuṅga-Lokanātha in Samataṭa [SE Bengal] (samataṭe jayatuṅga-lokanātha) | Mahāviśva-Lokanātha in Koṅkan [Coastal Maharashtra] (koṅkane mahāviśva-lokanātha) | D-D | |||

| Fol.200v (Ch. 28 ends) | Vasudhārā in Kanci in South India [Kancipuram, Tamil Nadu] (dakṣiṇāpathe kaṁcīnagare vasudhārāḥ) | Oḍḍiyana-Mārīcī (ottiyana-mārīcī) [Swat Valley, Pakistan] | B-D | |||

| Fol.202v (Ch. 29 ends) | Kurma-stūpa in Odisha (oḍradese kurmmastūpaḥ) | Mañjughoṣa in China (mahācīne maṁjughoṣaḥ) | D-A | |||

| Fol.214v (Ch. 30 ends) | Vainakā-syama-Caitya, Tirabhukti [Mithila, N. Bihar] (tirabhutau vainakā-syamacaityaḥ) | Khaḍga-caitya in Kanheri, Koṅkan [Coastal Maharashtra] (koṅkane kṛṣṇagirau khaḍgacaitya) | D-A | |||

| Fol.216v | Haladī-Lokanātha in Varendra (varendrā-haladī-lokanāthaḥ) | Candranavihāra (by Vulbhukavītarāga) in Supacanagara [Sopara Monastery] (supācanagare vulbhukavītarāgakṛta-candranavihāraḥ) | D-A | |||

| Fol.218v | Marṇṇava- Lokanātha-Caitya in Konkan [Coastal Maharashtra] (valivaṅkāṇa-koṅkaṇe marṇṇava-lokanātha-caityaḥ) | Śrī-Dhānya caitya in Ambu [Amaravati?](ambuviṣaye śrīśrīdhanyacaityaḥ) | D-A | |||

| Fol.220v | Caitya of Pratyekabuddha peak, Kanheri, Koṅkan [Coastal Maharashtra] (koṅkaṇe kṛṣṇagirau pratyekabuddha-śikhara-caityaḥ) | Tātīhā-Tārā in Rādha [W.Bengal] (rāḍhe tātīhā-tārāḥ) | A-D | |||

| Fol.221r (Ch.31 ends) | Lokanātha in Potalaka (śrīpotalake lokanāthaḥ) | Bhṛkuṭī-Tārā in Potalaka (śrīpotalake bhṛkuṭī-tārāḥ) | B-B | |||

| Fol.222r (Ch.32 ends) | Two-armed Mārīcī-caitya (dvibhujamārīcī-caityaḥ) | Jeweled lotus flower (no caption) | Disease dispelling Bhaiṣajya-bhaṭṭāraka Vajrāsana Buddha (ārogasālībhaiṣajya-bhaṭṭāraka-vajrāsanaḥ) | ?-? | ||

| Fol.222v (Colophon page) | Buddha’s birth at Lumbini (no caption) | Descent from the Trayatriṁśa heaven at Saṁkasya (no caption) | Monkey’s offering of honey at Vaiśāli (no caption) | |||

| Fol.223r (Post Colophon continues) | Taming of a mad elephant at Rājagṛha (no caption) | Miracle at Śravāsti (no caption) | Māravijaya, Enlightenment at Bodhgaya (no caption) | First sermon at Sarnāth (no caption) | Parinirvāṇa at Kuśinagara (no caption) | |

- Color coding system for geo-data specificity level.

- Green: A Level (a known site identifiable with matching geo coordinates), 15.

- Blue: B Level (town/city level centroid geo coordinates), 9.

- Orange: C level (town/city level info given but unidentified; state/region level centroid), 14.

- Yellow: D level (region/state level centroid geo coordinates), 28.

- Purple: E level (cosmological, no geo data), 3.

- White: unidentified, 7.

- White: no caption, 1.

- Grey: last two folios with Buddha’s life scenes and no captions [could be A level], 8.

Notes

| 1 | For example, see the maps in (Sen 2006, 2014a, 2014b; Schwartzberg and Bajpai 1992, p. 28). |

| 2 | Despite being an early modern site, it is worth remembering the trans-sectarian and transregional importance of the Nagore Dargah in Tamil Nadu given the importance of Nagapattinam as a port city in the context of early medieval maritime connectivity across Monsoon Asia and Buddhist presence until the Cōḻa period (Akarsh 2019; Seshadri 2009; Kulke et al. 2009; Ray 2018). As the final resting place and shrine of the sixteenth-century Sufi pir (saint) Shahul Hamid of Nagaur [Nagore] (c. 1513–1579), it attracts both Muslim and non-Muslim (mainly Hindu) devotees as observed and discussed by Vasuda Narayan (2006). Unlike other Sufi dargahs as a resting place of a Sufi saint, Shahul Hamid Nagori’s dargah is replicated in two other locations in Southeast Asia, one in Georgetown, Penang, Malaysia, and another in Singapore (Asher 2009). The miracle-working Sufi Saints whose stories/hagiographic accounts are filled with water-themed miracles—Sevea calls them “wave-surfing saints”— connected disparate communities across the sea through their shrines (Asher 2009; Sevea 2022). Asher notes how even today Muslim men going on a journey over water invoke Shahul Hamid in their prayers before, during, and after a water-bound journey (Asher 2009, p. 248). |

| 3 | “Monsoon Asia” is used here to emphasize the interconnectivity across South and Southeast Asia through sea routes; monsoon winds connected many shores of South and Southeast Asia and further to the east (to China and beyond). The concept of Monsoon Asia as a geo-cultural category is helpfully articulated by Sri Lankan archaeologist Senake Bandaranayake (Bandaranayake 2012, pp. 24–25), and further elaborated by Acri (2023). |

| 4 | Bopearachchi suggests reading Buddhist iconography at a more meta level along with Buddhist narratives and known historical evidence on trade whereas Kim (2021) suggests reading Buddhist iconography at a micro level to consider the processes and stories of their composition and making. |

| 5 | This is a huge change from when I first examined the manuscript at the library in 2002. There was limited access to the manuscript’s images as the only reproductions of the folios available after the on-site research were published studies, which had limited color images, and microfilms and color slides that I ordered from the library for a fee. The Cambridge digital library has revolutionized the way we access and study millennia-old palm-leaf manuscripts and will open a new era of manuscript culture studies. The library’s blog post celebrates the availability of this manuscript in its post from 9 May 2015. See https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/features/the-1000-year-old-manuscript-and-the-stories-it-tells (accessed 23 January 2025). |

| 6 | Beal’s translation of Buddhist records was published in 1884, and Foucher published his detailed study of this manuscript and the Asiatic Society manuscript of the same text A.15 in 1900. Despite its early publication, the eleventh-century date of the manuscript probably diminished its value for colonial researchers obsessed with the idea of original Buddhism and associated sites. |

| 7 | The prominence of the Konkan sites in this eleventh-century manuscript may also support the substantial presence of Esoteric Buddhist activities until this period as suggested by Mallinson’s (2019) recent study of the Konkan site of Kadri. |

| 8 | If the first wave of Esoteric Buddhism’s movement across Asia (documented by Chemburkar and Acri in their map) brought about the spread of what the Tibetan classification system calls the Yoga Tantra and the centrality of Vairocana (i.e., Mahāvairocana of the Vairocanābhisambodhi sūtra), the second wave may be characterized by the rise of the transgressive tantras (the Mahāyoga/yoginī tantras, also known as the Anuttarayoga Tantra in the Tibetan classification system of Buton Rinchen Drup [bu ton rin chen ‘grub 1290–1364]) with the centrality of Akṣobhya. |

| 9 | In the pothi-format manuscript tradition, a pagination system is developed from early on partly because the folios are not bound like a codex. For a helpful table of numerals and letter numerals in medieval Sanskrit manuscripts, see (Bendall 1883). |

| 10 | These two wooden covers are most likely supplied with the manuscript later: both are painted beautifully on the interior, but they are stylistically different from each other. Both covers’ paintings are also stylistically later than the painting inside the manuscript on palm-leaf folios. It is possible that the manuscript was given a fresh makeover when it was “rescued” in 1139 (Nepala Samvat 259) with a new painting on the book covers. One of the covers perhaps got mixed up with another manuscript’s cover by accident or it could have been damaged and was refurbished with a comparable book cover from another manuscript. |

| 11 | For an assessment of the circulation of Prajñāpāramitā textual sources across the Asian maritime realm (especially the hymns and spells associated with this tradition) see Bianchini (2024). |

| 12 | Thus, one can easily find words that begin with “lh-” in a classical Newari dictionary. According to Alexander von Rospatt, lhaṁ makes more sense in Newar phonology, and he suggests that it may mean “stone” or “rock”, which is lvahaṁ or lhvaṁ in modern Newari. Alexander von Rospatt personal communication, 5 July 2021. |

| 13 | “nepālamaṇḍalasvalaṁkāraṇāyasamyak śrīlhamvihāra iti sarvajanānurāgo yasmin vibhāti vacanaṁ sugatasya sasvat [śaśvat]” Add.1643, folio 222 verso, line 5. |