1. Introduction

Much existing youth ministry literature consists of anecdotes, personal stories, pastors’ accounts of experiences in a single context, or proposed methods of ministry that had not been systematically implemented or evaluated. Very little of the youth ministry literature is based upon empirical research. This article discusses preliminary findings from an ongoing doctoral research project that seeks to develop empirically based models of youth ministry, approved by the Edith Cowan University Human Research Ethics Committee. It is hoped that such models will be useful for the training of youth pastors. The research reported in this article examines the sources of influence on youth pastors when they design youth ministry programmes. In interviews, youth pastors were asked about what had influenced their approach to youth ministry, about their initial motivations for joining youth ministry, and their formal education and training.

In this article, ‘youth ministry’ refers to programmes that churches run for young people, and the group will be referred to as a ‘church youth group’. We use the term ‘youth pastor’ to describe those who lead youth ministry programmes that are related to a church. Youth pastor has been chosen as an inclusive term, because the alternative terms, such as ‘youth minister’, ‘co-ordinator’, or ‘NextGen pastor’, are either ambiguous—for example, ‘minister’ often denotes being ordained, and some pastors in this study were not ordained—or are denomination specific. ‘Pastor’ is also useful because it implies pastoral care, and support for wellbeing and or development of group members. When referring to the youth pastor’s career, this will be described as ‘youth pastorship’ to differentiate the personal career from the programme offered by the pastor.

This research findings contribute to the body of knowledge about youth ministry programme design, to youth ministry training design, and to a sociological perspective on youth ministry. This is an important area for exploration, and by starting with how youth pastors understand youth ministry, this may offer insights valuable for training of youth pastors.

3. Previous Studies

There have been some Australian and some international empirical studies on youth ministry practices. The context varies between countries, and this review of literature focuses first on youth ministry in Australia and then compares this with international studies, noting the contextual differences. There is limited empirical literature that focuses on the reasons youth pastors get involved in youth ministry, the formal and informal influences on the practices of youth pastors, and the models of practice youth pastors use to inform the design of their programmes.

Beginning with Australian literature,

Hughes (

2015) researched leadership in church youth groups in Australia (the results are also reported in

Hughes et al. 2016) but does not document the research methodology used. Hughes claims there is a lack of longevity in youth pastorship and a lack of formal training in youth pastorship in Australia. Hughes found that one youth pastor valued being seen as being caring, relatable, and relational—and part of this relatability according to young people was the age of the youth pastor. Hughes also contended that leaders of youth ministries acted as a bridge between the young people and the church as well as the broader community. Hughes identified some concerns in youth ministry—especially that youth pastors were often selected from among those who had already attended a local church/parish for a significant time. Hughes claims that this has some strengths in that the youth pastor will have some level of habitus and cultural capital in that church community; however, this might limit their ability to innovate due to monolithic church experiences. Hughes also cautioned that since relationships were seen as key to youth ministry, these should be guided by professional boundaries to prevent harm to young people. Additionally, youth ministry leaders in Hughes’ research tended to provide answers to young people and impart knowledge, which denied opportunities for young people to come to their own conclusions or deeply explore difficult issues. This implied a need for youth ministry leaders to learn skills not only in organisation, but also in critical reflective practice, dynamicity, and adaptability. While Hughes’s research offers some interesting findings, the omission of discussion of research methodology limits the replicability of the study and impedes judgements about their generalisability.

In Sydney, Australia,

Rymarz (

2019) studied how ‘lay’ youth ministers from Catholic parishes view their role. Rymarz’s research revealed why lay youth ministers entered into ministry, how they felt towards their ministry, their view of the role, and what contributed to their retention. Becoming a youth minister was conceptualised as an extension of their faith commitment, as a way of taking ownership of their faith, and as a meaningful use of their skills and youth ministry experiences. They viewed their role in both evangelical and relational terms: teaching young people about Jesus and being a supportive presence for young people. While participants reported they found their ministry fulfilling, some faced challenges in communication of expectations with the parish priest and sometimes held different understandings of the purpose of youth ministry. They felt a lack of job security, and the pay was too low to support a long-term career or for financial autonomy. They were aware of the insufficiency of resources for the youth ministry and felt frustration with respect to the limited capacity and potential loss of livelihood. Rymarz found that a supportive priest who gave positive and constructive input and a supportive community of faith were the biggest contributors to youth minister retention.

In South Africa,

Aziz et al. (

2017) researched Baptist youth pastors. The South African context of youth ministry differs culturally from that of Australia. Unlike many countries, South Africa has had an increase in people identifying as Christian since 2001 (

Forster 2024;

Statistics South Africa 2004). This may explain why

Wyngaard (

2015) described giving an explicitly Christian message as part of a community development programme, and that this aligned with community expectations. In a country where more than 80% of the population identify as Christian, public Christian messages are seen as normal, whereas such an approach would be seen as unusual in Australia. Aziz et al. described the role of a youth pastor as being caring, relatable, and relational—much like

Hughes (

2015) and

Hughes et al. (

2016). Aziz et al. chose to interview church senior pastors whose role usually implies seniority over a whole church congregation and perhaps other ministers within the same congregation. It is an interesting choice to have senior pastors describe the role of a youth pastor rather than the youth pastor themselves, because they would, assumedly, have less recent or direct knowledge of the role. Senior pastors described expecting youth pastors to hold formal theological qualifications and to have an understanding of youth development. This is an interesting expectation as, based upon the Western Australian context, theological degrees did not contain information about youth development. No information is provided about whether theological degrees in South Africa contain study of youth development.

Youth ministry was described by Aziz et al. as a transitional role—an expectation of general theological training that youth pastorship was a stepping stone towards ordained ministry rather than long-term ministry with young people being a career. This is consistent with the stated expectation that youth pastors were preferred to be under the age of 35, which echoes findings by

Hughes (

2015). Senior pastors also describe the role of youth pastors in evangelical terms or faith formation terms (either conversions or growing the faith of Christian young people or both), as well as in practical terms, for example, to organise and deliver the youth programme. It would have been interesting to know the perspectives of the youth pastors themselves on these issues.

In the United States,

Anderson and Frazier (

2018) researched the factors that contributed to 10-plus years of tenure in youth ministry by Church of Christ youth pastors—similarly to

Rymarz (

2019). As with the other literature, the role of a youth pastor was seen as being caring, relatable, and relational; however, contrary to

Hughes’s (

2015) and

Aziz et al.’s (

2017) findings, Anderson and Frazier’s study included youth pastors over the age of 60 who had tenures of over 10 years. The religious culture in the USA differs from the Australian context. Expressions of faith are very public in America, and frequently used as a tactic to garner political support (

Possamai 2008), as exemplified by Donald Trump posing with a Bible while being photographed by media (

Whitaker 2020). Youth ministry is presented as a highly respected career in the USA, and this is reflected in the plethora of youth ministry training degrees offered by US colleges (

Senter 2014). In contrast, a youth ministry degree is rare in Australia (

Hughes 2015).

The findings by Anderson and Frazier indicate that relational approaches, team approaches, practicing humility (for example, listening to the voices of young interns), and youth pastors taking on menial tasks (rather than delegating these to interns) were seen as contributing to long tenures. Youth pastors interviewed felt that their youth ministry degrees were not useful, despite their prevalence, but that training in counselling skills, management skills, psychology, and conflict management were more helpful. This finding implies that youth pastors with long tenures did not see their role as being primarily about youth faith formation, but gave greater prominence to support of young people, understanding young people, managing teams, and managing relationships.

Also in the USA,

Ji and Tameifuna (

2011) studied youth pastors through the perspective of Seventh Day Adventist (SDA) school students. Young people were surveyed about their perceptions of the denomination, local church, youth group, and their youth pastor. Once again, being caring, relatable, and relational was seen as the role of a youth pastor, and as most impactful for young people too. The youth pastor was also seen as facilitating thought-provoking and interesting programmes for young people as well as opportunities for young people to participate in leadership. The youth pastor had to demonstrate they were caring for there to be an impact on attitudes towards the SDA denomination. The research demonstrates that being perceived as relational, engaging, empowering, and caring were important characteristics for a successful youth pastor.

As part of a doctoral thesis,

Moser (

2019) analysed the reflections of multiple people involved in youth ministry at a single church in Canada, and compared this with perceptions of students who were studying youth ministry at a college in Canada. The cultural position of Christianity in Canada is similar to Australia, as similar proportions of the population identify as Christian and as no religion, and young people express similar attitudes towards faith (

Halafoff et al. 2020;

Statistics Canada 2024;

Watts 2025). Hence, Canadian research about youth pastors might be closer to Australian contexts compared with the USA. Moser found that youth ministry in Canada mostly focused on events such as weekly youth group meetings, as well as camps, retreats, and mission trips. Some youth ministry programmes were designed for ‘non-churched’ young people, while others were designed purely for churched young people.

Moser studied attractional youth ministry models—models that were intentionally designed to attract unchurched young people. Moser did this by interviewing people who were involved in youth ministry about their experiences with attractional models. The research was undertaken at the church where he was serving as the youth pastor at the time of the interviews. This potentially raises concerns about dependent power relationships in the research. He also interviewed youth ministry college students that he taught, which raises similar concerns. Moser found that attractional styles of youth ministry were ineffectual because they hide the Christian message, discourage commitment, create drop-in communities (rather than a caring community), and do not attract or retain young people. Moser concludes by offering a way forward in terms of youth-friendly (inclusive) churches, a style which strongly reflects the opinions of his doctoral supervisor, Malan Nel (see

Nel 2001). The credibility of the study is reduced because there is no demonstrated connection between the study findings and his conclusion. The credibility of the study is also affected by the potential bias in the research methodology due to seemingly unmanaged power relationships.

Being mindful of contextual differences, overall, there is a consensus in the literature that youth pastors should be caring and relational. Internationally, this is the most commonly reported practice identified by youth pastors, young people, and senior pastors. It appears that, apart from in the USA, youth pastors often lack tenure and tend to see youth ministry as a transition to other forms of ministry—perhaps due to poor support, poor remuneration, and the expectation of ‘aging out’ of youth pastorship. Additionally, there are some concerns about the adequacy of training: the South African study reported conflicting expectations; in Australia, there is a lack of formal youth ministry training; and in the USA, training is readily available but was not identified as valuable or relevant by participants. Given that there is limited research in Australia and elsewhere, the findings from the literature need further investigation in an Australian context as well as internationally.

There were notable gaps in the literature about what influences youth pastors’ conceptualisation of their role and activities. Only

Rymarz (

2019) described Catholic youth ministers’ reasons for becoming youth ministers, and there is no research on whether such reasons are similar elsewhere and cross-denominationally. Research on how youth pastors conceptualise and implement their programmes, as well as research in terms of methods and what they do, was identified as a gap in the literature. Hence, this study seeks to answer these questions and others about pastors’ influences and approaches with respect to their programme design.

4. Methods

Research approved by the Edith Cowan University Human Research Ethics Committee was conducted between November 2023 and April 2024 through a series of semi-structured interviews with 20 youth pastors who represented 19 churches. Some pastors ministered at multiple churches, and some churches had two youth pastors, who were interviewed together. The youth pastors represented five denominational groups, with three from Anglican churches, three from Baptist churches, five from Catholic parishes, three from Church of Christ/other [COC] churches, and six from Non-Denominational/Pentecostal [ND/P] churches. Youth pastors were asked about their approach to youth ministry, including the reasons they began working or volunteering in youth ministry, the training they received, what influenced them, and their methods used. These interviews were recorded and transcribed and then analysed using Nvivo (

https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/) for memoing of themes and Microsoft Excel for axial coding.

The interview data was analysed from a sociological perspective drawing upon Goffman’s ‘framing analysis’, which iteratively poses the question of ‘what is happening now’? (

Denzin and Keller 1981;

Hill 2014). The resulting explanation is called a ‘frame’ (

Hill 2014) and helps to make meaning of situations (

Cress 2015). Frames can come from natural explanations (e.g., people are running around, converting oxygen into carbon dioxide) or social explanations (e.g., people are having fun) (

Hill 2014). The frames transform the event and are built from pregiven myths and explanations (

Denzin and Keller 1981). Framing analysis is useful for micro sociological studies (i.e., not useful for macro studies) (

Hill 2014) and has been applied to a study of Catholic liturgies by

Cress (

2015). Sociology will be used as a method of conceptualising youth ministry and determine training needs. Sociology as a discipline is relevant to the study of religion because “While faith might seem personal, it always has a social dimension” (

Singleton 2023, p. 326). Hence, the authors contend, it is an appropriate tool for analysis in a study of youth pastor motivations and role conceptualisations. The analysis was applied to the processes youth pastors use when they develop their programmes. In the analysis, the researchers iteratively pose the question ‘what is happening now’, first in terms of frames for youth pastor ‘activities’ and ‘purposes/goals’ and secondly in terms of ‘motivations’, ‘key influences’, and the pastors’ formal education and qualifications.

5. Results and Discussion

Applying Goffman’s idea of frames, four frames were identified as influential to the way youth pastors designed their programmes. These frames were as follows: goals, initial motivations for working in youth ministry, key influences as identified by youth pastors (informal learning), and formal training.

5.1. Frame One: Goals and Metrics

Youth pastors engaged in a multitude of activities as part of their programmes; however, the most common activities were giving a talk (all youth pastors), facilitating fun games (all but one church), and facilitating small groups (75% of youth pastors). Worship with music was not common but was an integral aspect of youth ministry for those that used this approach. Youth pastor goals and metrics of success were analysed to find common and salient themes. During the axial coding phase, it became clear that themes of ‘person-centred’, ‘doctrine-centred’, ‘transcendent’, ‘family inclusive’, ‘outreach focused’, ‘responsive’, and ‘fun’ emerged from the data. These were repeatedly checked against transcripts to ensure no data had been excluded. Youth pastors’ goals, activities, and metrics were then analysed to determine what portion of their goals, activities, and metrics fitted into each theme. A mean of these percentages was then calculated for each goal to determine what degree each youth pastor exhibited each theme.

These percentages are used to make the goals, practices, and metrics of each youth group comparable, and to attempt bracketing of the researchers’ own biases in interpreting the data, recognising that applying a quantitative interpretation to qualitative data has limitations and cannot be treated as statistically precise. Youth pastors were not asked specifically how they would weight their goals for ministry; however, when a youth pastor repeats a goal theme multiple times, it demonstrates the importance of that theme to that youth pastor. For example, church 1 had a total of four goals, three activities, and three metrics. Three of their goals were person-centred (75%), two of their activities were person-centred (67%), and two of their metrics were person-centred (67%), providing a mean weighting of 69% for person-centred. This calculation was repeated for each theme for each church, and figures were rounded since they are indicative rather than statistically precise. Most youth pastors exhibited most or all the categories to varying degrees.

Doctrine-centred refers to when youth pastors saw the goal of youth ministry as teaching young people about Christian doctrine through sermons and bible studies. They measured their success through changes in young people’s behaviour, young people’s curiosity to know more, decisions/responses (such as conversions), a clear given talk, and young people’s testimony with respect to changed lives. Similar models used by other authors include Christian discipleship and Biblical hermeneutic models by

Canales (

2006), the first of which is too broad to be useful—since a broad spectrum of activities could be determined to be discipling (including those without any active impartation of teaching doctrine)—and the second is too specific to a particular method of interpreting the Christian Scriptures. Doctrine-centred finds a middle ground between these two by describing when youth pastors focused on teaching young people the doctrines of the Christian faith. Hence, a doctrine-centred focus transforms “a programme for young people” into “Young people are learning correct doctrine.”

Transcendent goals were reflective of a desire for young people to connect with God, such as through worship, prayer, and reconciliation, and were measured through young people’s emotional expressiveness during worship times. Transcendent was chosen over spiritual awareness (

Canales 2006) or spiritual accompaniment (

Green 2015) due to the broad interpretation of spirituality. Transcendent contains greater specificity of connecting with God through spiritual experiences, which is one aspect of spirituality (

Green 2015). A transcendent focus transforms “a programme for young people” into “Young people are experiencing God.”

Family inclusive refers to youth pastors whose goal was to engage the parents of young people through programmes, seminars, or through interpersonal care. Usually, the motivation behind this goal was the belief that family was the greatest influence on a young person’s faith. Family was also a common feature of youth ministry literature (

Hughes 2013;

Neufeld 2002;

Singleton et al. 2021;

Surdacki 2002), where writers encouraged youth pastors to involve the family, or discussed the strong influence of the family on young people’s faith. A focus on being family inclusive transforms “a programme for young people” into “a programme that empowers families to disciple their children.”

Outreach goals were focused on reaching unchurched young people by designing outreach programmes (such as schools ministry) and were measured through metrics such as numbers of conversions. The Funnel Model of youth ministry (

Lukabyo 2022;

Moser 2019),

Senter’s (

2001) missional model and strategic model, and the Gospel Advancing Model by

Stier (

2015) all have similarities to the focus on outreach; however, ‘Outreach’ makes it clear that the focus of youth ministry efforts is upon those outside of the church—those who do not attend church. This focus transforms “a programme for young people” into “We are allowing non-Christians to hear about who Jesus is.”

Responsive (a term borrowed from

Marion 2024) churches desired to respond to the needs of young people or the surrounding suburb through awareness of their needs and adapting programmes to suit their needs. A focus on being responsive transforms “a programme for young people” into “we are meeting young people’s needs.” Fun goals were focused on facilitating fun and measuring success through how much fun young people appeared to have. This aspect is discussed very little in the literature, apart from objections to focusing on fun (such as

Root 2007); however, youth pastors insisted that this was a crucial tool for youth ministry and was a common goal and metric. Fun as a focus transforms “a programme for young people” into “a fun programme that young people want to go to.”

These seven goals of youth ministry were then used to compare various frames of meaning to understand youth pastor actions.

5.2. Frame Two: Initial Motivations

Youth pastors were asked about their initial motivations for joining youth ministry, in any capacity, whether as a volunteer or as a leader, and then asked about their motivations for taking on the leadership position of youth pastor/minister/co-ordinator. Their motivations were grouped into seven categories: firstly, being asked by a previous youth pastor to take their place or by a senior pastor or trainer to consider stepping into youth ministry (or to shift from volunteering into a paid youth pastor role). Twelve (12) youth pastors fitted into this category. Nine youth pastors were motivated by their experiences of youth ministry as a young person. For this group, their experience, whether positive or negative, motivated them to give young people the experience of being part of a church youth group, and influenced their thinking about programme design, whether it was to provide a similar experience to other young people or an experience that differed from their own. Seven youth pastors described feeling called to become a leader in youth ministry through spiritual experiences. These included, coincidentally, reading a relevant Bible verse or talking to an existing youth pastor about their desire to become a youth pastor, who then responded by saying they had been intending to ask them to assume the role. Six youth pastors were motivated by evangelism, which included such things as a desire to see young people understand and adopt Christian teaching. One youth pastor said that, for them, evangelism occurred whilst they were struggling with their identity formation, echoing the ‘storm and stress’ of G. Stanley Hall (

Lukabyo 2018;

Ryan 2019). Another six described relational motivations, such as their own positive relational experiences in youth ministry, and/or a desire to maintain relationships they had with their youth leaders, similar to

Rymarz’s (

2019) findings. Other, less common themes included the desire to give back and to keep having and creating fun.

Analysis: Motivation and Emergent Patterns

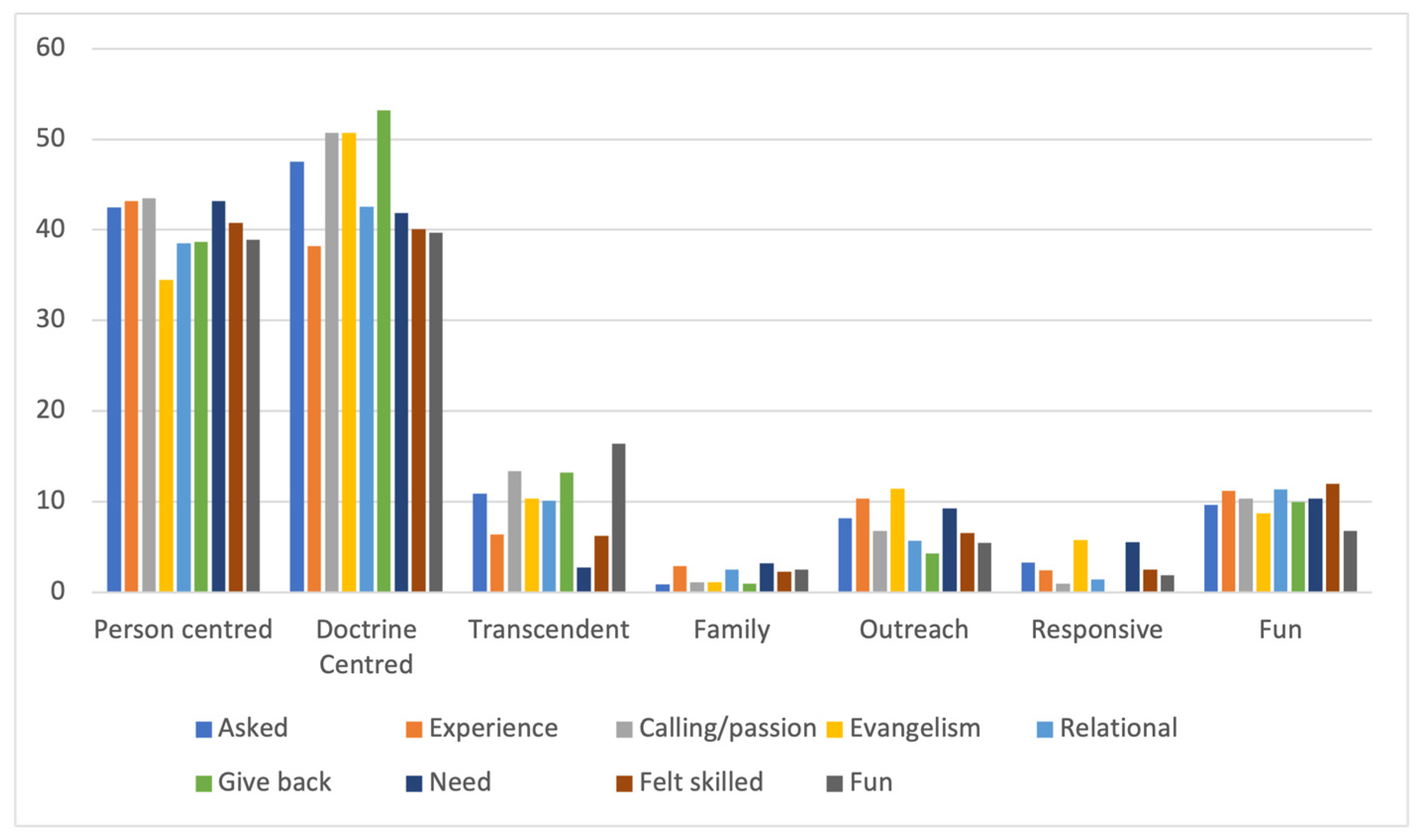

Themes with respect to motivations were then compared with the key foci described earlier to determine any interesting trends, and whether a youth pastor’s motivations related to the focus of their ministry. This comparison was then charted into a bar graph, as per

Figure 1.

The graph demonstrates some surprising findings. For example, one might expect that those who have a person-centred focus would have motivations closely related to experience and relationships. While experience was high among person-centred youth pastors, calling/passion was the highest. Simliarly with doctrine-centred youth pastors: one might have expected motivations such as evangelism—specifically motivations for young people to know about Christianity—to have been the key motive, but ‘give back’ was the highest for doctrine-centred youth pastors. One might have expected calling (spiritual experiences of calling) to be highest for those with high transcendent goals, but the most common motivation was fun. However, one could logically feel a sense of spiritual calling to secular professions such as youth work or medicine too, so calling might not always be linked with highly transcendent activities. Experience was the most common motive amongst those highly focused on family. Evangelism was the most common motive amongst responsive-focused youth groups, and feeling skilled was the most common motive amongst those who focused on fun. The only unsurprising motive was for outreach-focused youth groups: the motive of evangelism was most common amongst highly outreach-focused youth groups. This may suggest that motivations may have sometimes influenced the way that youth pastors practiced their ministry, or perhaps their current goals and activities coloured the way that youth pastors thought about their early youth ministry practice.

Drawing upon a Goffman perspective, youth pastors may have reframed what they do through their own motivations for joining youth ministry initially. When youth pastors were asked to step into the role, some of the youth pastors described feeling ‘called’ to youth ministry, and may have interpreted their experience of being asked as part of this spiritual call to ministry. Those who did not use this frame may have interpreted this experience as a sense of being wanted, seen, and valued for one’s skills or personal attributes. Alternatively, they may have felt that since they were asked by others to step into the role of youth pastor, they had to live up to that person’s expectations. Hence, this may transform “I am leading a youth group” into “I am called to do this/I am entrusted to do this/Others believe I can do this/I have authority to do this” giving confidence to their actions and choices. Alternatively, it may have been “I am trying to live up to the expectations of those who asked me to take this role” producing pressure to perform with respect to their actions and choices. If a youth pastor is giving a talk, this may be transformed by the frame of being asked into “I have been called to give this talk/I am speaking the words that God has told me to speak/I have been entrusted to speak these words/I have authority to speak these words.” Alternatively, where this being asked was more of a pressure situation, this may manifest as a frame of, “I hope what I say meets the expectations of my church.”

Evangelistic motivations may transform leading a youth group into “I am bringing young people to know God, which is their greatest need.” In small groups, this could have transformed “young people are talking in groups” into “Young people’s identities are being formed in light of what God says about them.” Where experience-focused motives were positive, there may have been a desire to replicate those experiences, transforming “young people playing a game” into “Young people are having the same experience I had”; where negative, they may have wanted young people to have a different experience, transforming a game into “Young people are building relationships and having a better experience than I had.” Finally, some youth pastors described noticing a need, and some of these also described feeling that they had the skills to meet that need. Where not mentioned explicitly, this ability to meet a need may have been implied; that is, there was a need that they felt they could fill. This transforms “I am leading a youth group” into “I am keeping this youth group open”, or perhaps “I am doing something I am good at.”

5.3. Frame Three: Key Influences

Youth pastors were asked to identify what they believed was most influential in terms of the way they choose to facilitate youth ministry. The input of others was the most notable influence on youth pastors, with fifteen (15) of the twenty (20) identifying this as an influence on their youth ministry practice. Six were influenced by the previous youth pastor’s practices; for two of these this was a negative influence, with the youth pastor wishing to do the opposite of the previous youth pastor. Five were influenced by the senior pastor or other supervisors, which was usually described in positive terms. Another eight identified other youth pastors in their networks as being the biggest influence, because such networking enabled them to reflect on their practice and gain new ideas. Eight youth pastors identified books, authors, podcasts, or speakers that were influential on their practice. The most mentioned book was

Growing Young (

Powell et al. 2016b)—three of the eight mentioned this book, one of whom mentioned it in negative terms. Other notable books and authors included

Sticky Faith (

Powell and Clark 2011) and

You Lost Me (

Kinnaman and Hawkins 2011). Others described listening to multiple Christian speakers, theologians, or podcasts that spoke on the Christian faith generally, which resulted in internal paradigms for ministry. Seven youth pastors described their own experience as being most influential in terms of their practices. Four of these constructed their approach to youth ministry upon learning through ‘trial and error’, which implies reflective practice. The remaining three described their experiences as a young person, both positive and negative experiences, as being influential with respect to their goals and activities. The least commonly mentioned influence was training or study: five youth pastors specifically described this as influencing their practice, with four describing their formal studies and one referring to informal training. Sixteen youth pastors did not find their formal studies to be influential with respect to their practices, or sufficiently influential to be worth mentioning, or, at the least, did not think of their studies when asked what influenced the way they do youth ministry.

Analysis of Emergent Patterns

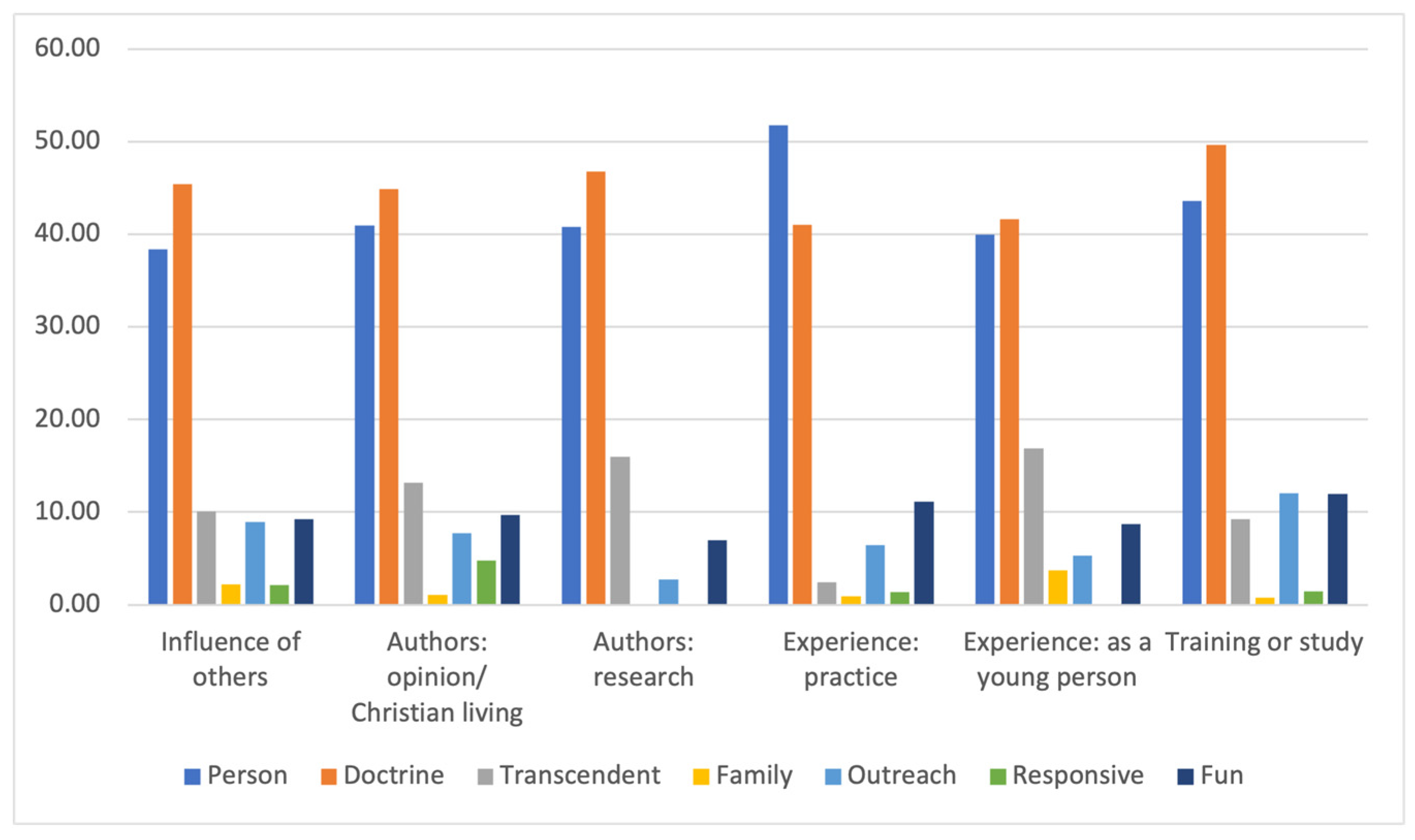

Further analysis compared identified influences with the focus of their ministry, out of which we created a graph for visual representation in

Figure 2. ‘Person-centred’ youth pastors mostly identified their practice experience in youth ministry (for example, trial and error) as having the greatest influence. The highest ‘doctrine-centred’ weightings were from those who found their studies or training to be most influential; however, all weightings for this category were quite close and within the percentage range of 40–50%. The results were similar for youth pastors who had a high weighting in terms of ‘outreach focus’ and ‘fun focus’. For the latter, the close second-highest weighting was for practice experience. The highest weighting for ‘transcendent focus’ was among those who identified their own experiences as a young person as influential. For ‘family focus’, experience received the highest weighting. This was most likely because there was one youth pastor who was highly focused on being family inclusive, and this youth pastor was mostly influenced by their own experiences as a young person and by other youth pastors. This is not dissimilar to the case related to the highest weighting for responsive, which was from those who identified opinion or Christian living authors as being influential—this youth pastor identified a book they had been given on Christian living as the most influential with respect to their ministry.

Goffman’s impression management (

Poole and Germov 2023) may explain why the finding related to the ‘input of others’ was common. Youth pastors may have been seeking to manage how others viewed them—how they perceived what their supervisors, predecessors, and other youth pastors in their network think of their practice. This could result in the youth pastor desiring to adopt certain practices that they believed would be perceived positively by such individuals, resulting from a motivation to meet expectations and ‘perform’ for them. This could act as a frame of “I must do youth ministry this way to impress [person].” From a framing perspective, many of these influences might also add a frame of “this is the right way to do this,” but with a different reason. For example, “This is the right way to do this, because …

… experts say it is” (theologians, research);

… this is how experts taught me to do it” (training);

… this is what worked for me/this is what didn’t work for me” (experience as a young person);

… I have learned from mistakes” (experience in youth ministry);

… Significant people I know do it this way (or, tell me to do it this way), and I trust/respect them” (others—input/emulating).

For example, the meaning of a game could be transformed through the frame of a person-centred focus into “relationships are being built”. Then, the added frame of the influence of research could reframe the game into, “Young people are finding a reason to stay/this is a research evidenced practice”. For a talk, the youth pastor might frame what they are doing in terms of what

Growing Young (

Powell et al. 2016a) says about keeping the gospel central in order for young people to encounter God: “This talk is focusing on the gospel of Jesus, which means young people are encountering God.” The talk is no longer just a talk, but an encounter. Youth pastors may facilitate small groups because of their experiences, transforming “a group of people talking” into “people finding belonging, like I did.” For those who facilitate worship, they may frame it similarly, transforming “people are singing” to “People are experiencing God in worship, just like I did.”

5.4. Frame Four: Training

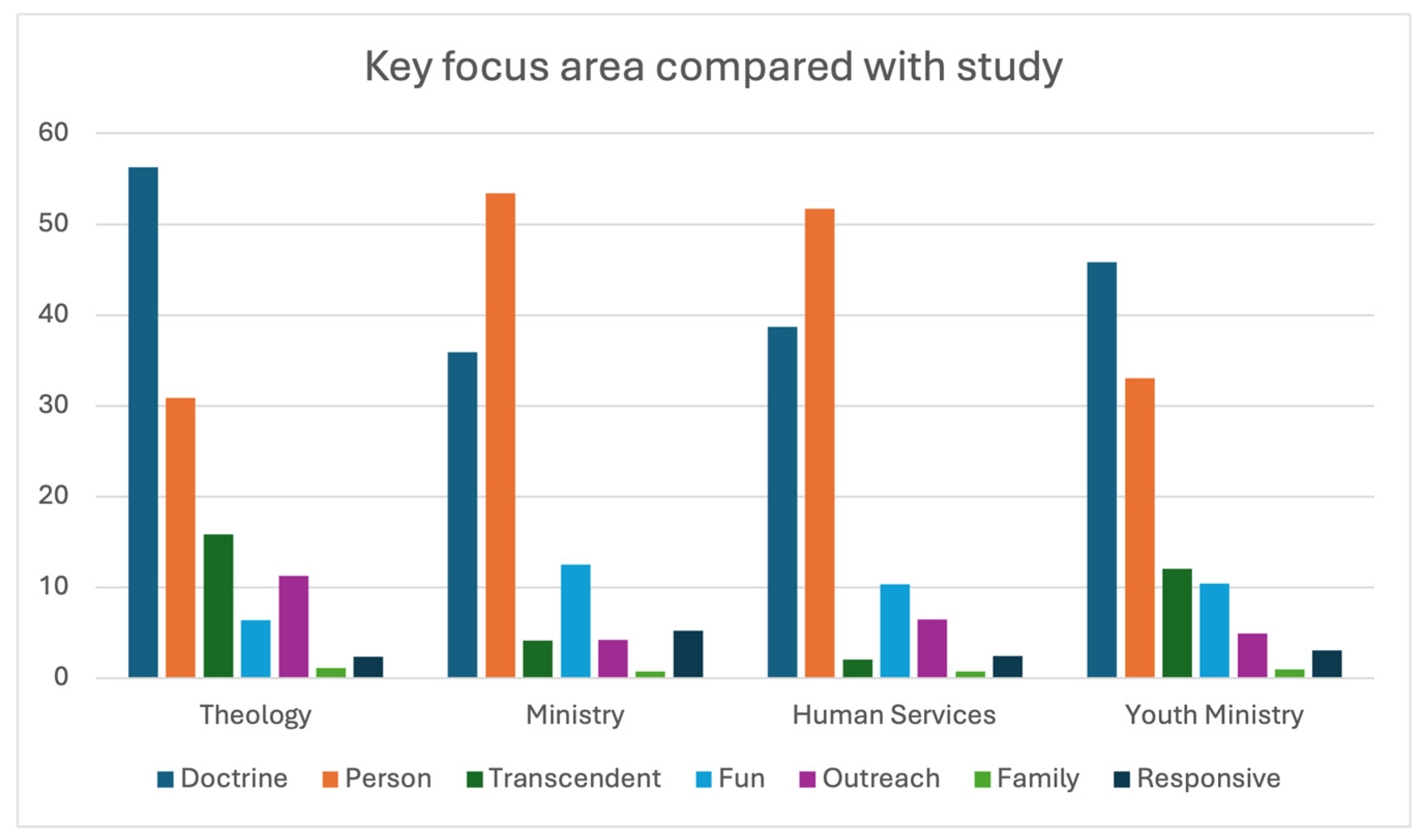

The third and final frame to be examined is the influence of training that youth pastors had. These qualifications were categorised by theme and then compared with how many youth pastors per denomination held that qualification. Most youth pastors had some form of training—only two had no higher education or vocational training, meaning that 18 youth pastors held 23 degrees. The most common of these was Bible college, such as general ministry (6) or theological training (5). Only Catholic youth pastors held a youth ministry qualification (4), which has been counted separately because it was a denominational-specific qualification. One of these Catholic youth pastors also held additional vocational qualifications in unrelated fields. Three youth pastors held human services degrees; one of these had nursing, theology, and leadership degrees. Two did not hold a ministry or theology degree: one held a youth work degree from a Christian Registered Training Organisation and one held a teaching degree. These degrees were then compared with the key foci of each youth pastor, graphed in

Figure 3.

This graph compares the key focus of each youth pastor with what they studied; the two youth pastors who stated ‘none’ were excluded in order to avoid biasing the data. These figures were created by entering the weighting for each focus into an Excel spreadsheet. The mean weighting for each study area was then calculated for each focus area. For example, youth pastors 3, 4, 6, 9, 12, and 13 all held theological degrees, and their weightings for doctrine-centred were 40, 52, 62, 59, 42, 69, and 69, respectively. The mean of these numbers was taken, yielding 56%. This process was then repeated for each theme and each study area. Where youth pastors held more than one degree, the results were entered into both areas of study, so that this graph represents a comparison of the degree and the main focus. This graph demonstrates that those who had studied theology were more likely to be highly doctrine focused, were the most transcendent focused and outreach focused, and were lowest in terms of person-centred approaches. Second, those who studied ministry were more likely to be highly person focused, were the most fun focused and the most responsive, and were lowest in terms of doctrine focus and outreach. Third, those who studied human services (this includes youth work, nursing, and teaching) were not the highest or lowest with respect to any focus. However, they were higher in terms of person-centred approaches than doctrine-centred approaches. Finally, those who studied youth ministry were also not the highest or lowest in terms of any focus, but were higher with respect to doctrine-centred approaches than person-centred approaches. All youth ministry studies were Catholic, and this may suggest something either about the specific training or about the denomination. It would be interesting to investigate the influence of youth ministry-specific training as compared with theology training; however, due to the fact that only Catholic youth pastors studied youth ministry specifically, it is not possible to do so in the current study, but it may be worth investigating in future research. Furthermore, the practices of Catholic youth pastors do quite reflect the priorities and focus areas of the

Australian Catholic Bishops Conference (

2014) document. This document gives a vison of Catholic youth ministry as being focused on spiritual growth, evangelisation, and use of young people’s gifts, which explains the high doctrine focus and high transcendent focus. It also explains why Catholic youth pastors were more likely to engage young people as leaders, and why they were frequently engaged in outreach to Catholic schools. Hence, the above-mentioned differences in terms of youth ministry studies may actually reflect denominational characteristics.

While only 20% of youth pastors identified their studies as having influenced the way they do youth ministry, it is possible that training had some generic influence, but this is not entirely clear. Perhaps the influence was not perceived consciously but had affected the way they had framed the needs of young people and the purpose of youth ministry. Or perhaps youth pastors chose degrees of study that matched their goals and values. For graduate studies, this may have resulted in a reframing of “I am facilitating a youth group” into “Young people are learning correct theology”. Perhaps ministry graduates reframed youth ministry as “Young people are building relationships/young people are seeing Jesus reflected in these relationships”. Human services graduates might have framed youth ministry in terms of “This is what works in a professional setting”, thereby perhaps subconsciously framing activities with professional modalities. Finally, perhaps Catholic youth ministry graduates framed their activities in terms of, “This is how we have been taught to do this.”

6. Implications and Conclusions

Many things seem to act as paradigmatic frames for interpreting youth ministry practice: a youth pastor’s experiences, initial motivations for entering youth ministry practice, inspirations, and training. This study found that similar activities (such as a talk, games, small groups) may have very different framings by youth pastors. This means that it is necessary to explore and critique such framings of activities when youth pastors are being prepared for youth pastorship. This implies that the knowledge and skills required by youth pastors are varied.

The clearest was the influence of others, such as the youth pastor that participants encountered when they were a young person or when they were a volunteer. Others included peer youth pastors that were in the networks of the youth pastor, or the youth pastors’ own senior pastors or supervisors. Few youth pastors credited their training as influential; however, there were some interesting patterns that warrant further investigation. The correlations open the possibility that formal study may have some unconscious influence over youth pastors’ practices, even though pastors identified informal influences more frequently.

Cooper (

2024) included informal learning as informal education and described the complementary roles informal and formal educational methods can have. Informal peer education has strengths in developing practical skills for youth ministry but is limited by the peers that the youth pastor has. Formal education, when well designed, offers opportunities to strengthen critical thinking and to consider various ideologies and knowledge in terms of research-based and conceptual and theoretical knowledge, but formal education may struggle to accommodate differences in individual starting points or differences in learning styles, with limited opportunities for development of practical skills. In Western Australia, formal youth ministry training was only available to Catholics. Formal studies combined with informal education supported by regular professional supervision and strong mentoring offer many opportunities to overcome the limitations of formal education, but such studies are currently not credentialled.

The first point arising from this study is that there appears to be a mismatch between the formal education and training that most youth pastors receive and the knowledge and skill demands of their practice. For example, youth ministry training could provide practical skills for relationship building to support relational practices, and youth ministry courses might also offer curriculum design training on how to develop suitable activities to meet their goals, but formal courses are not readily available to provide this curriculum content in most denominations. Other topics should prepare youth pastors to critically consider the various things that have influenced their thinking (experiences, denomination, motivations) with respect to the purpose of youth ministry and to compare these to evidence-based models of youth ministry. Finally, courses should prepare students to learn from observing others while critically reflecting on their own practice. These skills would enable youth pastors to maximise their informal learning. Formal education (accredited, structured, and curriculum-based learning) could be strengthened through experience-based informal learning activities supported by active mentoring and peer learning. Both approaches can be supplemented by a commitment to lifelong self-directed learning for individuals, teams, and managers of organisations.

Secondly, youth pastors found reflecting on their own experiences highly valuable. Reflective practice facilitates lifelong learning and self-directed learning. Personal experience was a motivation for entering ministry. Youth pastors described having valuable positive relationships, and evidently, they wanted to recreate these relational experiences for the young people they ministered to. Experience was also relevant to how youth pastors planned their youth ministry. They framed the purposes of youth ministry within their own experiences and in terms of trial and error with respect to what worked and what did not work previously. Reflecting upon one’s own experiences can have the advantage of learning from mistakes, and critical self-reflection is a key aspect to many human services fields (

Modderman et al. 2022). However, according to

Modderman et al. (

2022), effective critical reflection requires support to elucidate hidden assumptions and biases and to reframe experiences in the context of ethical practice and research literature. Additionally, reflecting on one’s experiences as a young person can bias a youth pastor to provide the kinds of experiences that they would value, which may not be valuable for all kinds of young people. This may especially be so for the young people who do not remain in youth ministry.

Thirdly, there were some clear relationships between study areas and the key focus (goals, activities, metrics) that youth pastors used. Some patterns emerged, for example, correlating human services and ministry degrees with a person-centred approach, but the strongest pattern was between theology degrees and a doctrine-centred approach. A strong foundation in theology can certainly be helpful to ministry practice; however, there is usually little room in such degrees for consideration of key theories and concepts for good practice, or engagement with relevant and recent research regarding young people and work with young people. Recent research, for example, indicates that a dogmatic (distinct from the theological concept of dogma) approach to faith inculcation is a frequent cause for young people to leave the church (e.g.,

Fazzino 2014;

Kinnaman and Hawkins 2011;

Mullen 2020,

2025;

Mullen and Cooper 2023;

Vaclavik et al. 2020). This is not to say that a doctrine focus within youth ministry is inappropriate; however, a framing of youth ministry upon doctrinal and theological grounds may result in neglecting the needs of young people. Hence, youth pastors might consider learning skills in building strong holistic relationships characterised by power sharing, democratic dialogue, and respect, as is demonstrated in studies by

Thompson (

2017) and

Bright et al. (

2018). Perhaps a youth ministry that begins with young people’s holistic needs and engages them in democratic dialogue is what youth ministry in Western Australia requires.

Finally, this discussion also offers some limited critique of a Goffman framing analysis of practices. Goffman-like framing analysis is useful to explain what is happening, and to bring new understanding to how different perspectives can transform a person’s experience of a youth program or transform how a youth program is designed. Goffman analysis has not, however, sufficiently explained why youth pastors hold such views or whether the framings reflect youth pastor thinking. This is a limitation of Goffman’s framing analysis: it cannot offer explanations for practices. However, it does offer a framework for critically thinking about one’s practices by analysing various perspectives on said practices through the multiplicity of experiences and sources of learning.

This research has contributed new information to the body of knowledge around youth ministry in Australia. The research has revealed some of the key motivations that youth pastors hold regarding their youth ministry practice, and the influences upon their practice. It has contributed to knowledge that current educational preparation is not perceived as influential on practice by the majority of youth pastors. Some suggestions are offered with respect to potential changes needed to support the effective training of youth pastors. Additional analysis is now being completed that compares the views of youth pastors with those of young people, and perhaps with volunteer youth leaders, as required.