Evangelism in Translation: A Critical Study of Missionary-Scholar Walter Henry Medhurst’s Rendering of Chinese Agricultural Classic Nongzheng Quanshu

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Medhurst’s Motivation for Rendering Chinese Agricultural Knowledge in Nongzheng Quanshu

3. Medhurst’s Translation Methodology for Rendering Agricultural Knowledge in Nongzheng Quanshu

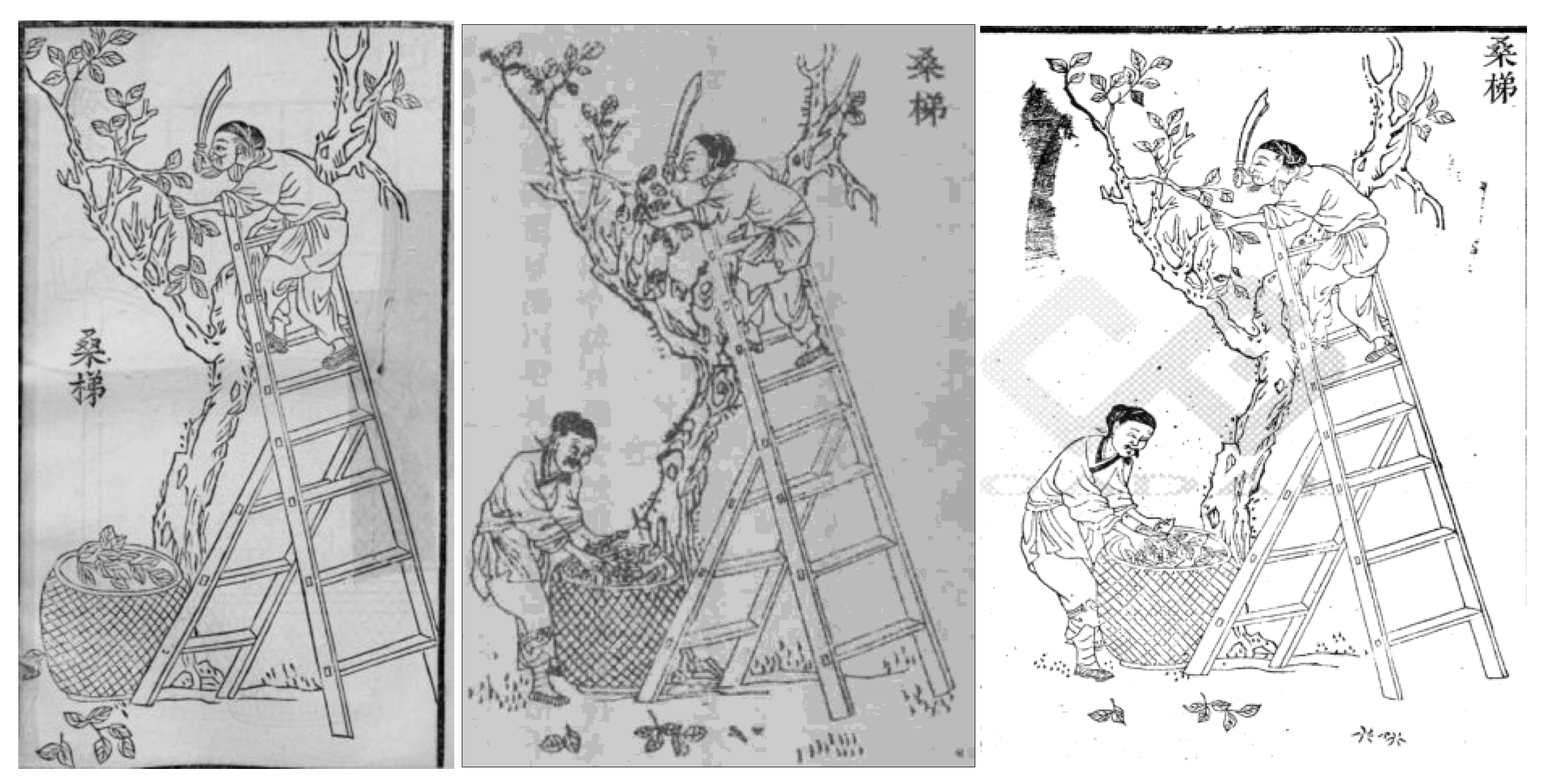

3.1. Chinese Edition

3.2. Agricultural Terminology

4. Translation Quality of Medhurst’s English Translation of Nongzheng Quanshu

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In 1816, Medhurst was dispatched to Malacca by the LMS. His correspondence with this organization from 1817 to the 1840s is held in the archives of SOAS, University of London. Part of his correspondence has been digitized; see https://archives.soas.ac.uk/search/all:records/0_50/all/score_desc/%20Walter%20Henry%20Medhurst (accessed on 15 July 2025). |

References

- Alam, Ishrat. 1999. History of Sericulture in India to the 17th Century. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 60: 339–52. [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor, Kathryn. 2018. Translation and Paratexts. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bohr, P. Richard. 2001. The Legacy of William Milne. International Bulletin of Missionary Research 25: 173–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, Kingsley, and Christopher Hutton. 1998. Linguistics in Cross-Cultural Communication: From the Chinese Repository to the “Chinese Emerson”. Journal of Asian Pacific Communications 1–2: 145–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1972. Esquisse d’une Théorie de la Pratique. Genève: Droz. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, Francesca. 1984. Science and Civilization in China. Vol. 6, Part 2: Agriculture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, Francesca, Vera Dorofeeva-Lichtmann, and Gorges Metailie. 2007. Graphics and Text in the Production of Technical Knowledge in China. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgman, Elijah Coleman. 1835. The Bible: Its adaptation to the moral condition of man. The Chinese Repository 7: 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Brookes, Richard. 1736. The General History of China. London: John Watts. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, Andre. 2020. Confucius, a Chinese christian prophet? The translation of Chinese classics by the Priest Joaquim Guerra and the religious dialogue in 20th century. International Communication of Chinese Culture 7: 485–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Elizabeth H. 2007. Converting Chinese Eyes: Rev. W. H. Medhurst, “Passing,” and the Victorian Vision of China. In A Century of Travels in China. Edited by Douglas Kerr and Julia Kuehn. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, I-Hsin. 2016. From God’s Chinese names to a cross-cultural universal God: James Legge’s intertextual theology in his translation of Tian, Di and Shangdi. Translation Studies 3: 268–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Youbing. 2008. On the Characteristics of the Various Stages of Sinology in England: As Seen from the Viewpoint of Research in Classical Chinese Literature. Newsletter for Research in Chinese Studies 3: 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, Pauline Hope, and Jessie P. H. Poon. 2009. Weaving Webs of Faith: Examining Internet Use and Religious Communication Among Chinese Protestant Transmigrants. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 2: 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, Hugh. 1911. Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, J. Nicoll. 1981. Dissenters & National Journalism: “The Patriot” in the 1830s. Victorian Periodicals Review 2: 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Lianjian. 2015. Weiqu qiuchuan: Zaoqi laihua xinjiao chuanjiaoshi hanying fanyi shilun 1807–1850 委曲求傳:早期來華新教傳教士漢英翻譯史論 1807–1850 [The Chinese-English Translation by Early Protestant Missionaries to China]. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Huaiqing 段懷清. 2006. Wanqing yinguo xinjiao chuanjiaoshi “shiying” zhongguo celue de sanzhong Xingtai jiqi pingjia 晚清英國新教傳教士”適應”中國策略的三種形態及其評價 [Three Approaches to Cultural Accommodation: British Protestant Missionaries in Late Qing China and Their Historical Significance]. Shijie Zongjiao Yanjiu 世界宗教研究 [Studies in World Religions] 4: 108–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Mengzhi 方夢之. 2019. Fanyi Xue Cidian 翻譯學辭典 [A Dictionary of Translation Studies]. Beijing: The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Girardot, Norman J. 2002. The Victorian Translation of China: James Legge’s Oriental Pilgrimage. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gow, Ian. 2024. Two-Way Knowledge Transfer in Nineteenth Century China: The Scottish Missionary-Sinologist Alexander Wylie (1815–1887). Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hanan, Patrick. 2003. The Bible as Chinese Literature: Medhurst, Wang Tao, and the Delegates’ Version. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 1: 197–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Shaobin. 2014. Translation as Creative Treason: The Missionary Translation Projects in Late Imperial China. Comparative Literature: East & West 19: 112–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, John. 2016. Mission to China: The Life of Walter Henry Medhurst. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Xiaochun 洪曉純. 2022. Mai dusi dui God zhi hanyu yiming de sikao licheng tanwei 麥都思對God之漢語譯名的思考歷程探微 [An Investigation into Walter Henry Medhurst’s Evolving Conceptualization of Chinese Renditions for “God”]. Zongjiao xue yanjiu 宗教學研究 [Religious Studies] 2: 218–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Jie 侯傑. 2025. Minzu zhi zhishi zai shengchan: Zhen shan mei yuanze xia yuwai youji Haidao yizhi yingyi tanjiu 民族志知識再生產: “真善美”原則下域外遊記《海島逸志》英譯探究 [Knowledge Reproduction in Ethnography: A Study on the English Translation of the Overseas Travelogue The China Man Abroad under the Principle of “Truth, Goodness, and Beauty”]. Zhongguo kuangye daxue xuebao (shehui kexue ban) 中國礦業大學學報(社會科學版) [Journal of China University of Mining & Technology (Social Sciences)], 1–13. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/32.1593.C.20250707.1009.002.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- House, Juliane. 2015. Translation Quality Assessment: Past and Present. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Can 黄灿. 2017. Shengtai Fanyixue Shijiao Xia Nongzheng Quanshu Cansang Pian Zhong Nongye Shuyu De Yingyi Fenxi 生態翻譯學視角下《農政全書》桑蠶篇中農業術語的英譯分析 [An Eco-Translatologic Approach to the C-E Translation of Agricultural Terms in Mulberry and Silkworm Chapter of Nongzheng Quanshu]. Master’s thesis, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Xiaohua 蔣驍華. 2010. Dianji yingyi zhong de “doangfang qingdiaohua fanyi qingxiang” yanjiu 典籍英譯中的 “東方情調化翻譯傾向”研究——以英美翻譯家的漢籍英譯為例 [From Cultural Fidelity to Stylized ‘Chinoiserie’: Tracing the Orientalizing Tendency in Western Translations of Chinese Texts]. Zhongguo Fanyi 中國翻譯 [Chinese Translators Journal] 4: 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, Wang, and Michael Cavayero. 2025. Exploring Early Buddhist-Christian (Jingjiao (sic)(sic)) Dialogues in Text and Image: A Cultural Hermeneutic Approach. Religions 5: 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Thoralf. 2011. Conversion to Protestant Christianity in China and the ‘supply-side model’: Explaining changes in the Chinese religious field. Religion 41: 591–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, Dieter. 1981. Silk Technology in the Sung Period (960–1278 A.D.). T’oung Pao 1–2: 48–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, Dieter. 1988. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, part 9: Textile Technology: Spinning and Reeling, New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kwong, Luke S. K. 2023. Between End and Means: Tensions in Timothy Richard’s China Career. Monumenta Serica 71: 167–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, John T. P. 2010. Cultural and Religious Negotiation: Missionary Translations of “The Anxious Inquirer” into Chinese. Sino-Christian Studies 10: 81–121. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, John T. P. 2023. Moral Cultivation and Divine Revelation: James Legge’s Religious Interpretation of the Yijing (Book of Changes). Religions 8: 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge, Jame. 1939. Chinese Classics Vol.3 Plate-1. London: Henry Forwde. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Haijun 李海軍. 2017. Shiban shiji yilai nongzheng quanshu zai yingyu shijie yijie yu chuanbo jianlun 18世紀以來《農政全書》在英語世界譯介與傳播簡論 [A Study on the Translation of A Complete Treatise on Agriculture in the English World Since 1738]. Yanshan daxue xuebao (Shehui kexue ban) 燕山大學學報(哲學社會科學版) [Journal of Yanshan University (Philosophy and Social Science)] 6: 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Rui, and Annette Skovsted Hansen. 2018. A remarkable compilation shift A genealogical study of Medhurst’s Chinese and English Dictionary (1842–1843). Historiographia Linguistica 3: 263–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Xinde 李新德. 2015. Mingqing Shiqi Xifang Chuanjiaoshi Zhongguo Rushidao Dianji Zhi Fanyi Yu Quanshi 明清時期西方傳教士中國儒道釋典籍之翻譯與詮釋 [Translation and Interpretation of Chinese Confucian, Daoist and Buddhist Canons by Western Missionaries during the Ming and Qing Dynasties]. Beijing: The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yafeng, and Jingmin Fu. 2025. The Translation of Physics Texts by Western Missionaries During the Late Ming and Early Qing Dynasties and Its Enlightenment of Modern Chinese Physics. Religions 1: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yafeng, and Shengbing Gao. 2025. Translators and gospelers: The roles of western missionaries in China during the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties from the perspective of cultural capital. Asian Journal of Social Science 3: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Linhai 劉林海. 2016. Maidusi shenxue sixiang chutan 麥都思神學思想初探 [On the Theological Thought of Walter Henry Medhurst]. Beijing Shifan Daxue Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) 北京師範大學學報(社會科學版) [Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Sciences)] 4: 127–37. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Liyi 劉立壹. 2019. Jingxue shixue hanxue: Maidusi shujing yingyi yanjiu 經學·史學·漢學:麥都思《書經》英譯研究 [Classics, Historiography, and Sinology: A Tripartite Study of Walter H. Medhurst’s English Translation of the Book of Documents]. Guoji hanxue 國際漢學 [International Sinology] 2: 169–75. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Ming 劉明. 2005. Lun Xu Guangqi de zhongnong sixiang jiqi shijian 論徐光啟的重農思想及其實踐——兼論《農政全書》的科學地位 [From Theory to Field: Xu Guangqi’s Agrarian Reform and the Scientific Evaluation of Nongzheng Quanshu]. Suzhou Daxue Xuebao 蘇州大學學報 [Journal of Soochow University] 1: 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, David. 1857. A Narrative of Dr. Livingston’s Discoveries in South-Central Africa from 1849 to 1856: Reprinted by Arrangement from the “British Banner” Newspaper: With an Accurate Map. London: Routledge and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Mingyu. 2013. US-American Protestant Missionaries and Translation in China 1894–1911. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature & Culture: A Web Journal 2: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mackerras, Colin. 1999. Western Images of China, rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Thomas William M. 1858. Christianity in China: A Fragment. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- McAlester, Gerard. 2000. The Evaluation of Translation into a Foreign Language. In Developing Translation Competence. Edited by Christina Schäffner and Beverly Adab. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 229–42. [Google Scholar]

- Medhurst, Walter H. 1838. China: Its State and Prospects. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. [Google Scholar]

- Medhurst, Walter H. 1842. Chinese and English Dictionary. Batavia: Parapattan. [Google Scholar]

- Medhurst, Walter H. 1845. A Glance at the Interior of China: Obtained During a Journey Through the Silk and Green Tea Districts. Shanghai: The Mission Press. [Google Scholar]

- Medhurst, Walter H. 1846. The Shoo King, or the Historical Classic. Shanghai: The Mission Press. [Google Scholar]

- Medhurst, Walter H. 1849a. Dissertation on the Silk-Manufacture and the Cultivation of the Mulberry. Shanghai: The Mission Press. [Google Scholar]

- Medhurst, Walter H. 1849b. On the True Meaning of the Word Shin, as Exhibited in the Quotations Adduced Under That Word in the Chinese Imperial Thesaurus Called the Pei-wan-yun-foo. Shanghai: Mission Press. [Google Scholar]

- Medhurst, Walter H. 1849c. The China Man Abroad: A Desultory Account of the Malayan Archipelago. Shanghai: The Mission Press. [Google Scholar]

- Milne, William Charles. 1857. Memoir of the Late Rev. Dr. Medhurst. The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 14: 161–66. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Frederic. 1859. Synopsis of the Known Asiatic Species of Silk-producing Moths. The Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 27: 237–70. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Robert. 1812. Horæ Sinicæ: Translations from the Popular Literature of the Chinese. London: T. Williams and Son. [Google Scholar]

- Muirhead, William. 1857. The Parting Charge. A Sermon Preached in Commemoration of the Death of the Rev. W. H. Medhurst, D. D. Shanghae: North-China Herald Office. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, Joseph. 1954. Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 1: Introductory Orientations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Old, Walter Gorn. 1904. The Shu King; or, The Chinese Historical Classic, Being an Authentic Record of the Religion, Philosophy, Customs and Government of the Chinese from the Earliest Times. London: Theosophical Publishing Society. [Google Scholar]

- Py, Fábio, and Isabella Carvalho Soares. 2023. Narratives of Differentiation and the Religious Rift at Goiabal Community in Campos dos Goytacazes. International Journal of Latin American Religions 8: 305–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, Valentin. 1978. The Home Base of American China Missions, 1880–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, C. 1849. Directions for the Cultivation of Cotton. The Chinese Repository 9: 449–469. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Jing. 2000. Wang Tao’s Christian Baptism. In Wang Tao and the Modern World. Edited by Kai Yin Lam and Man Kong Wong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Educational Publishing Company Ltd, pp. 435–52. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R. Wardlaw. 1906. Griffith John: The Story of Fifty Years in China. London: Religious Tract Society. [Google Scholar]

- Toury, Gideon. 2012. Descriptive Translation Studies–and beyond, rev. ed. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Tsien, Tsuen-hsuin. 1954. Western Impact on China Through Translation. The Far Eastern Quarterly 3: 305–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Hao 王皓. 2020. Shilun shijiu shiji houqi ouzhou hanxuejie de jiegou yu tezheng 試論十九世紀後期歐洲漢學界的結構與特徵 [An Exploratory Study of the Structure and Characteristics of European Sinology Circles in the Late Nineteenth Century]. Zhongguo wenhua yanjiu 中國文化研究 [Chinese Culture Research] 2: 167–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Marina Xiaojing. 2019. Western Establishment or Chinese Sovereignty? The Tientsin Anglo-Chinese College during the Restore Educational Rights Movement, 1924–7. Studies in Church History 55: 577–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Pei, and Mingwu Xu. 2024. Translation, transmission and indigenization of Christianity in nineteenth-century China: South-to-north travel of the disguised San Zi Jing by Medhurst. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 11: 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, Alexander. 1867. Memorials of Protestant Missionaries to the Chinese: Giving a List of Their Publications, and Obituary Notices of the Deceased. With Copious Indexes. Shanghae: American Presbyterian Mission Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, Alexander. 1897. Chinese Researches. Shanghai: Unknown. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Dibing 熊帝兵. 2021. Nongzheng Quanshu Guizhou liangshuben kanyinzhe Ren Shusen kaoshu 《農政全書》貴州糧署本刊印者任樹森考述 [Forensic Bibliography: Proving Ren Shusen’s Printing of the Guizhou Government’s Nongzheng Quanshu]. Henan Ligong Daxue Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) 河南理工大學學報(社會科學版) [Journal of Henan Polytechnic University (Social Sciences)] 3: 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Guangqiu. 2016. Medical missionaries in Guangzhou: The initiators of the modern women’s rights movement in China. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 22: 443–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Jun 許鈞. 2016. Lun fanyi piping de jieruxing yu daoxiangxing: Jianping fanyi piping yanjiu 論翻譯批評的介入性與導向性 [Toward a Theory of Intervention: The Orientational Paradigm in Translation Criticism]. Waiyu jiaoxue yu yanjiu 外語教學與研究 [Foreign Language Teaching and Research] 3: 432–41. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Shanshan 徐珊珊, and Qin Yao 姚琴. 2025. Bianyi lulun shiyu xia wenhua fuzaici de hanying fy yanjiu: Yi Nongzheng quanshu (Mumian) weili 變譯理論視域下文化負載詞的漢英翻譯研究——以《農政全書》 (木棉)為例 [A Study on Chinese-English Translation of Culture-Loaded Terms from the Perspective of Adaptive Translation Theory: A Case Study of the Nongzheng Quanshu (Cotton Section)]. Hanzi wenhua 漢字文化 [Sinogram Culture] 2: 163–65. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Wensheng 許文勝, and Boran Zhang 張柏然. 2006. Jiyu hanying mingzhu yuliaoku de yinguo guanxi lianci duibi yanjiu 基於英漢名著語料庫的因果關係連詞對比研究 [A Corpus-Based Contrastive Study of Causal Connectives in English and Chinese Literary Classics]. Waiyu Jiaoxue Yu Yanjiu 外語教學與研究 [Foreign Language Teaching and Research] 4: 292–96. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Huilin. 2011. Theological Interpretation on the Sacred Books of China and Its Political Implication: A Case Study on James Legge’s Translation. Sino-Christian Studies 11: 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Zhiting 楊志亭. 2019. Feirencheng goushi zai keji yingyu zhong de yuyong gongneng jiqi fanyi 非人稱構式在科技英語中的語用功能及其翻譯 [Pragmatic Functions and Translation of Impersonal Constructions in Scientific English]. Waiguo Yuwen 外國語文 [Foreign Languages and Literature] 4: 110–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zabalbeascoa, Patrick. 2000. From Techniques to Types of Solutions. In Investigating Translation. Edited by Allison Beeby, Doris Ensinger and Marisa Presas. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 117–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Huiyan 曾慧妍. 2024. Nongzheng Quanshu zaoqi yingyi yu chuanbo tezheng tanxi 《農政全書》早期英譯與傳播特徵探析 [On Early English Translation and Dissemination of Nongzheng Quanshu]. Yingyu Guangchang 英語廣場 [English Square] 5: 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Guogang. 2001. Mingqing Chuanjiaoshi Yu Ouzhou Hanxue 明清傳教士與歐洲漢學 [Jesuit Bridgebuilders: The Missionary Foundations of European Sinology]. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Tao. 2007. Protestant Missionary Publishing and the Birth of Chinese Elite Journalism. Journalism Studies 6: 879–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ziyue 張紫玥. 2022. Nongzheng Quanshu Cansang Pian Maidusi Yiben Nongxue Shuyu Yingyi Yanjiu 《農政全書》“蠶桑篇”麥都思譯本農學術語英譯研究 [A Study on C-E Translation of Agricultural Terms in Medhurst’s Translation of “Silkworm and Mulberry Volumes” of Nongzheng Quanshu]. Master’s thesis, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Translation Techniques | Count | Percentage | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zero Translation + | Transliteration | 3 | 2% | 後高 Hów-kaon |

| 2 | Transliteration + literal translation | 8 | 62% | 四出 Szé-ch’hǔh worms | |

| 3 | Transliteration + in-text annotation | 1 | 連 lëen, joined sheets | ||

| 4 | Transliteration + literal translation + in-text annotation | 19 | 蚖珍 yuen-chin, (or April) worms | ||

| 5 | Literal translation | 57 | 雞桑 chicken mulberry | ||

| 6 | Free translation + in-text annotation | 2 | 36% | 添梯 layer, or rampin-board | |

| 7 | Free translation | 48 | 蛾眉杖子 rail of the reel | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y. Evangelism in Translation: A Critical Study of Missionary-Scholar Walter Henry Medhurst’s Rendering of Chinese Agricultural Classic Nongzheng Quanshu. Religions 2025, 16, 1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091156

Wang Y. Evangelism in Translation: A Critical Study of Missionary-Scholar Walter Henry Medhurst’s Rendering of Chinese Agricultural Classic Nongzheng Quanshu. Religions. 2025; 16(9):1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091156

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yanmeng. 2025. "Evangelism in Translation: A Critical Study of Missionary-Scholar Walter Henry Medhurst’s Rendering of Chinese Agricultural Classic Nongzheng Quanshu" Religions 16, no. 9: 1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091156

APA StyleWang, Y. (2025). Evangelism in Translation: A Critical Study of Missionary-Scholar Walter Henry Medhurst’s Rendering of Chinese Agricultural Classic Nongzheng Quanshu. Religions, 16(9), 1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16091156