1. Introduction

In recent years, equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) initiatives have gained growing visibility within academic spaces. Yet in the context of an increasingly hostile political climate—exemplified by initiatives such as Project 2025 in the US, the UK’s recent Supreme Court decision, and proposed cuts to PIP and Access to Work—scholarship and praxis that actively support, empower, and amplify the voices of marginalized communities have become not only necessary but urgent. In this paper we present the concept of being a ‘rebellious disruptor’ in order to crip and neuroqueer an academic conference space within the field of sociology of religion to facilitate collegiality and discussions on the emerging field of disability and religion. The field and discourse within sociology of religion is emerging, echoing the emergence of religion and gender about 20 years prior (

Neitz 2004;

Woodhead 2001), whilst theological discourse on disability theology, neurodiversity theology, and disabled and neurodivergent-led theology continues to grow (for example

Brock and Swinton 2012;

Hardwick 2021;

Jacobs 2019;

Jacobs 2023;

Reyes 2023;

Swinton 2012;

van Ommen 2023;

van Ommen and Waldock 2025;

Williams 2023). Neurodivergence, the state of having a bodymind that differs from what

Walker (

2021) calls the dominant societal standards of “normal”, is becoming increasingly understood as being part of EDI efforts (

Thomson and Gooberman-Hill 2024). Diversity amongst bodyminds is central to neuroqueer theory (

Walker 2022), an approach we have taken to being ‘rebellious disruptors’.

The term neuroqueer was developed by M. Remi Yergeau, Athena Lynn Michaels-Dillon, and Nick Walker (

Walker and Raymaker 2021), referring to the subverting of neurotypicality (i.e., having a ‘normal’ bodymind). Neuroqueer theory offers a generative framework for interrogating the normative structures that govern academic knowledge production and embodiment. Emerging at the intersection of neurodiversity and queer theory, neuroqueer approaches resist dominant biomedical and psychological paradigms that pathologize non-normative cognition, sensory experiences, and bodyminds. At its core, neuroqueering is an intentional act of subverting, disidentifying from, or refusing imposed standards of neurotypicality and cis-heteronormativity. As

Walker (

2021) describes, to neuroqueer is “to engage in practices and thought processes that resist the cultural scripts of normativity,” whether these pertain to cognition, communication, or relationality. Cripping similarly is an emancipatory process in which disabled people can assert power and control against able bodiedness (

McRuer 2006). Cripping as a term is reclaimed from ‘cripple’ in much the same way the term ‘queer’ has been reclaimed by queer people (

Sandahl 2003), and as

Sandahl (

2003, p. 27) argues, are “fluid and ever-changing”. Such stances disrupt not only dominant understandings of disability and neurodivergence, but also the institutional logics that reinforce rigid separations between intellect and affect, reason and emotion, and mind and body binaries deeply embedded in Western academic traditions and colonial knowledge systems.

In the context of the Sociology of Religion, neuroqueer theory compels us to question who is deemed a legitimate knower and what kinds of religious or spiritual experiences are considered credible or intelligible. In many ways, questioning who is deemed a legitimate knower and judging religious or spiritual experiences to be ‘credible’ directly reflects the notion of epistemic injustice. Epistemic injustice, as described by

Fricker (

2007) is an injustice based on an individual’s capacity as a knowledge bearer, where the individual’s claims are not seen as credible. One particular form of epistemic injustice identified by

Fricker (

2007), known as testimonial injustice, specifically where an individual’s testimony is deemed as lacking credibility by the listener (

Fricker 2007;

Dotson 2011). Disabled and neurodivergent ways of being have been silenced and it has been reported and noted in a variety of settings, notably within healthcare (

Blease et al. 2016;

Potter 2015) Therefore it is not a surprise that disabled and neurodivergent people can experience this within religious and spiritual groups and practices (see

Jacobs and Richardson 2022;

Jacobs 2023 for further information), as well as in academic and research spaces (

Dolmage 2017;

Mogendorff 2022).

Through us also drawing on queer of color critique and crip theory (

McRuer 2006;

Puar 2017) as well as epistemic justice and injustice (

Fricker 2007), neuroqueering allows for an epistemological expansion that accounts for embodied, affective, and nonlinear ways of knowing that have been excluded from academic spaces, and subject to epistemic and testimonial injustice. Marginalized lived experiences and ways of being face epistemic and testimonial injustice through ignorance and silencing (

Dotson 2011), shaped by majority expectations, in particular, expectations grounded in colonialism, whiteness, and neuronormativity.

By centering neurodivergent and disabled experiences, not as deficits to be accommodated but as sources of critical insight, we move towards a decolonial praxis that challenges the whiteness, ableism, and elitism of institutional life, as well as epistemic and testimonial justice. This is particularly vital in theological and social scientific studies of Religion, including sociology of religion, where dominant frameworks have often been shaped by Cartesian dualisms and colonial epistemologies that privilege disembodied rationality and universalized notions of “belief” (

Asad 1993;

Keller 2003;

Smith 1998). We argue that neuroqueering and cripping, then, become both an activist and affective intervention in challenging epistemic and testimonial injustice experienced, in this case, by disabled and neurodivergent people. It disorients the presumed neutrality of academic discourse and reclaims space for complexity, relationality, and difference as central to scholarly life.

In presenting our contributions to the SocRel Chair’s Response Day on Religion, Neurodivergence, and Disability, we demonstrate how centering access within formalized academic spaces is not merely a logistical concern, but an embodied, affective, and political act. By foregrounding neuroqueer and disabled modes of knowing, feeling, and relating, we unsettle dominant epistemic norms and open up space for otherwise marginalized ways of being. This approach to access constitutes a counter-hegemonic praxis that resists the normative, ableist, and colonial logics that continue to structure academic life. It is also an activist intervention; one that reimagines scholarship not as disembodied neutrality, but as relational, accountable, and radical in our approach to equitable inclusion and participation. Through using the SocRel Chair’s Response Day on Religion, Neurodivergence, and Disability as a site for ethnographic research and reflection, echoing

McCutcheon’s (

1997) assertions that meetings and conferences can be sites of ethnographic research, we demonstrate how we created a space that centers disabled and neurodivergent knowledge in relation to religion.

Positionality

In order to ground ourselves as ‘rebellious disruptors’, it is firstly important to outline our positionality and how this informs our research and praxis.

A: As a neurodivergent person, I frequently face exclusion, silencing, and power imbalances in the academy and within religion, and these are experiences I am therefore deeply reflexive of in my research and praxis (

Olmos-Vega et al. 2023), and it has often led to distinct feminist and queer approaches to how I work. I also remain sensitive to the fact that there are many neurodivergent experiences (

Walker 2021), echoing the fluidity of queerness. Furthermore, coming from an area of socioeconomic deprivation, I remain acutely reflective on the privilege I have amongst people in my community, yet also the discomfort of feeling ‘out of place’ within academic spaces and discourses. My work as a marginal scholar disrupts both disciplinary boundaries and normative ideas of autistic people’s experiences in lived religion, echoing my position as a ‘rebellious disruptor’.

B: My positionality is shaped by the intersecting experiences of being racialized, Muslim, a woman, and the first generation in my family to be born in Britain. These identities are not static but, following Judith

Butler (

1990), produced performatively through their entanglement with power, recognition, and resistance. They are also situated in what Homi

Bhabha (

1994) describes as the “third space,” a liminal zone in which cultural meanings are negotiated, hybridized, and contested. It is from this unstable, partial, and creative location that I engage with both scholarship and media practice.

Drawing from Michel

de Certeau’s (

1984) theories of bricolage and makeshift creativity, I explored how the women I worked with engage in subtle and often improvised forms of digital practice that operate within and against dominant narratives about Muslim womanhood. These tactics of reappropriation—what de Certeau might call “ways of operating” (

de Certeau 1984, p. 19)—enabled women to forge presence and agency through fragmented posts, religious memes, makeup tutorials, and diasporic humor. I read these as resistant strategies that complicate binaries between piety and modernity, secular and sacred, visibility and veiling.

Rather than follow conventional academic boundaries, I embraced a cross-pollination of disciplines, methods, and creative sensibilities. I am not interested in performing academic legitimacy through rigid metrics or disembodied objectivity. Instead, I approach scholarship as situated, relational, and often improvised in the spirit of what de Certeau saw as “making do.” Like the women in my research, I work with what is available, repurposing institutional spaces and scholarly conventions to forge new ways of seeing, knowing, and belonging.

To call myself a rebellious disruptor is not a performance of defiance for its own sake. It is a necessary stance that emerges from being consistently positioned as marginal, within the academy, within the media, and within society at large. My refusal to conform to institutional expectations is informed by a decolonial feminist politics that sees knowledge production as always implicated in histories of exclusion, violence, and erasure (

Mignolo 2009;

Tuck and Yang 2021). Informed by Bhabha’s concept of cultural hybridity and Butler’s work on precarity and relationality (

Butler 2004), my research centers those who operate in between and against dominant norms. As both a scholar and a filmmaker, I move through what

Bhabha (

1994) called the interstices—those in between spaces where agency emerges not as mastery but as everyday negotiation, tactical resistance, and imaginative reworlding.

2. Disruption and the Limits of the Counter-Hegemonic

In this paper, we call for a rethinking of how concepts such as resistance and opposition are framed in the context of religion, disability, and neurodivergence. While the term counter-hegemonic has been widely used within critical scholarship to signify acts of resistance against dominant social, religious, and institutional norms (see

Barreto 2019;

Carroll 2007;

Simms 1997), we argue that it often re-centers hegemonic structures rather than dismantling them. When we describe alternative practices as counter-hegemonic, we implicitly affirm the centrality and authority of the hegemonic system being opposed. This framing can limit the radical potential of work that is not only oppositional but also deeply creative, improvisational, and situated. However, rather than defining this solely through opposition, we advocate for disruption as a more productive lens that allows us to center creativity, friction, and epistemic disobedience without reaffirming the structures being challenged.

This reframing particularly echoes Dinah Murray’s phrase “productive irritant” (see

Monotropism n.d.), which underlines not only the importance of persistent activism as a means to change but also offers a powerful alternative to oppositional models of change. Writing from the perspective of autistic cognition,

Murray et al. (

2005) describe how autistic individuals can act as necessary disruptors in social and institutional systems. Their ways of communicating, perceiving, and responding often challenge taken-for-granted norms simply by virtue of their difference. In this way, autistic communication and lived experiences are not framed as problems to be corrected but as generative forms of cognitive activism (

Murray and Aspinall 2006). Murray’s understanding of activism does not require planned protest or strategic resistance. Instead, it is enacted through everyday ways of thinking, being, and doing that reveal the limitations and exclusions of dominant systems. This perspective aligns closely with how neuroqueer and crip theorists understand disruption—not as a grand act of refusal, but as a slow, messy, and embodied process of doing otherwise.

Such disruption was central to the SocRel Response Day we co-organized, which brought together scholars, activists, and practitioners to reflect on the intersections of religion, neurodivergence, and disability. A ‘Chair’s Response Day’ is a one-day symposium organized in collaboration with individuals who are a part of the British Sociological Association’s Sociology of Religion Study Group Committee. This is an annual event with different topics covered each year. This year’s (2025) topic was an EDI topic, of which the topic of ‘disability, neurodivergence and religion’ was decided upon and agreed by all members of the committee. The event was designed to center access, challenge academic norms, and affirm the value of embodied knowledge and care. We did not simply make the day more accessible; we collectively disrupted how academic knowledge is usually produced, shared, and valued. By prioritizing access and lived experience as foundational rather than supplementary, we created a space where neurodivergent and disabled scholars could speak and be heard on their own terms, creating space that centers epistemic and testimonial justice (

Fricker 2007). This included how we ‘recruited’ speakers and delegates for the day; firstly, we approached our keynote speaker, whose ethics and approach to working alongside marginalized groups echoed ours. We then placed an open call for speakers through two large sociology of religion email groups, as well as individually approaching potential speakers both ourselves through our known networks, and through our keynote speaker’s network. This allowed both scholars and practitioners to come forward as speakers—allowing for information that could be considered the ‘hidden curriculum’ in higher education (

Jackson 1968) to be given to speakers who were new to such events. Centering disabled and neurodivergent scholars was not a counter-hegemonic gesture aimed at institutional critique alone, but a reconfiguration of what scholarly practice could be. It made space for forms of knowledge and presence that are typically marginalized in academic religion.

Disruption, in this sense, does not have to mean total rupture. Following Michel

de Certeau’s (

1984) concept of bricolage, we understand these practices as forms of makeshift creativity and tactical improvisation. Bricolage describes how people make meaning through repurposing and reworking what is already available to them. It allows us to recognize the innovative ways in which people who have historically been excluded from the academy and from normative religious spaces create space for themselves. Rather than confronting hegemonic norms directly, they bend and reshape them in ways that may appear subtle but are deeply transformative. These forms of disruption are especially significant in the lives of neurodivergent and disabled individuals who are constantly required to adapt, translate, or conceal their differences in order to participate in public life. In refusing those demands and insisting on alternative modes of presence and knowledge production, they do not just resist hegemony; they offer entirely different ways of knowing and being.

We argue that by centering disruption, rather than simply opposition, we can more accurately reflect the layered and complex forms of agency that emerge from neuroqueer and crip engagements with religion and academia. These practices do not always announce themselves as resistance, but they destabilize the normative frameworks that structure belonging, authority, and participation. They do so not through abstract theory alone, but through embodied presence, relationality, and the politics of care. It is with this ethos that we organized the BSA Chair’s SocRel Response Day.

This can be described as an embedding affect that refers to the intentional integration of emotional, sensory, and relational considerations into the design and delivery of the SocRel Response Day, treating these as core components of access and decolonial praxis rather than secondary concerns (

Ahmed 2012). As the following section outlines in detail, this was enacted through concrete organizational choices that centered participant wellbeing, agency, and connection. These examples, from the structuring of time and space to the facilitation of dialog, illustrate how embedding affect functioned as both a guiding principle and a practical methodology.

3. Radical Hospitality and Disruption in Practice: Reflections on the BSA SocRel Response Day

The BSA Sociology of Religion Response Day on Religion, Neurodivergence, and Disability was far more than a typical academic event. It was a carefully designed space that embodied our values of care, disruption, embodiment, and refusal. From the outset, we aimed to move beyond conventional modes of conferencing and institutional engagement. We did not just want to bring radical ideas into the room; we wanted to host them in ways that reflected the epistemologies and lived realities from which they emerged. Drawing on Sara Ahmed’s critique of institutional diversity (2012) and Audre Lorde’s insistence that the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house (

Lorde 1984), we knew we had to think differently. What we created was not only radical in content, but radical in form. It was a place where pace, access, and relation took precedence over performance and polish.

We understood this project as a form of what Dinah Murray calls cognitive activism, a concept that highlights the political and intellectual work of neurodivergent communities who challenge dominant modes of thinking by embodying alternative ways of knowing and communicating (

Murray and Aspinall 2006). Murray’s notion of the productive irritant, developed in her work on autistic difference, helps us frame the event as a space that allowed friction to be held and processed in meaningful ways. We deliberately resisted academic habits of control and neutrality, creating instead a dynamic and relational space where the norms of excellence and productivity were suspended. The day operated through what Alison

Kafer (

2013) and Jasbir

Puar (

2017) describe as crip and queer temporalities, which resist linear progression in favor of complex and layered ways of being together. In this way, the day allowed us to embrace vulnerability, collective reflection and bodily presence as modes of knowledge.

We understood these moments of tension as what Anna

Tsing (

2005) describes as “friction”—the awkward, unequal, and often generative engagements that occur when different social worlds meet. In our case, friction arose between the commitments of disability justice and the procedural demands of institutional partners, producing both frustration and new possibilities for thinking otherwise. Rather than seeing friction as merely an obstacle, we treated it as an analytic lens, revealing the limits of dominant organizational logics and opening space for creative problem-solving. In this way, friction became a methodological tool as much as an organizational reality.

Although the Response Day took place within an institutional setting at King’s College London, it was shaped by principles that often sit at odds with institutional logic. Rather than positioning ourselves as oppositional to the university, we worked from within, insisting on a different vision and making access and care our starting points. This approach can be understood through

Kearney and Fitzpatrick’s (

2021) work on radical hospitality, which foregrounds relational openness and ethical responsibility as necessary conditions for transformative dialog. In every element of the event’s design, from speaker invitations to spatial layout, we asked: who is this space for, and what would make it feel like it belongs to them?

We structured the day around flexibility and choice. Panels were non-hierarchical. Contributors were invited to present in whatever format suited them best. We had optional breakout rooms, spacious breaks and sensory-aware planning. Access was centered throughout the event. This was not inclusion as an add-on; this was inclusion as a central method. In doing so, we also enacted a decolonial approach to event-making, one that, as Gloria

Anzaldúa (

1987) suggests, allows new ways of knowing to emerge through the tension and complexity of the borderlands. Importantly, this work was not carried out despite the institutional context. Rather, it showed that institutions can be receptive and responsive when we are insistent and clear in our demands. In organizing the logistics of the day, the events team at King’s College London were actively attuned to our requirements for the day. Once we established access was a priority, they applied a streamlined approach to all aspects moving forward. This was refreshing in view of some of the bureaucratic issues we faced organizing the event (which will be discussed later).

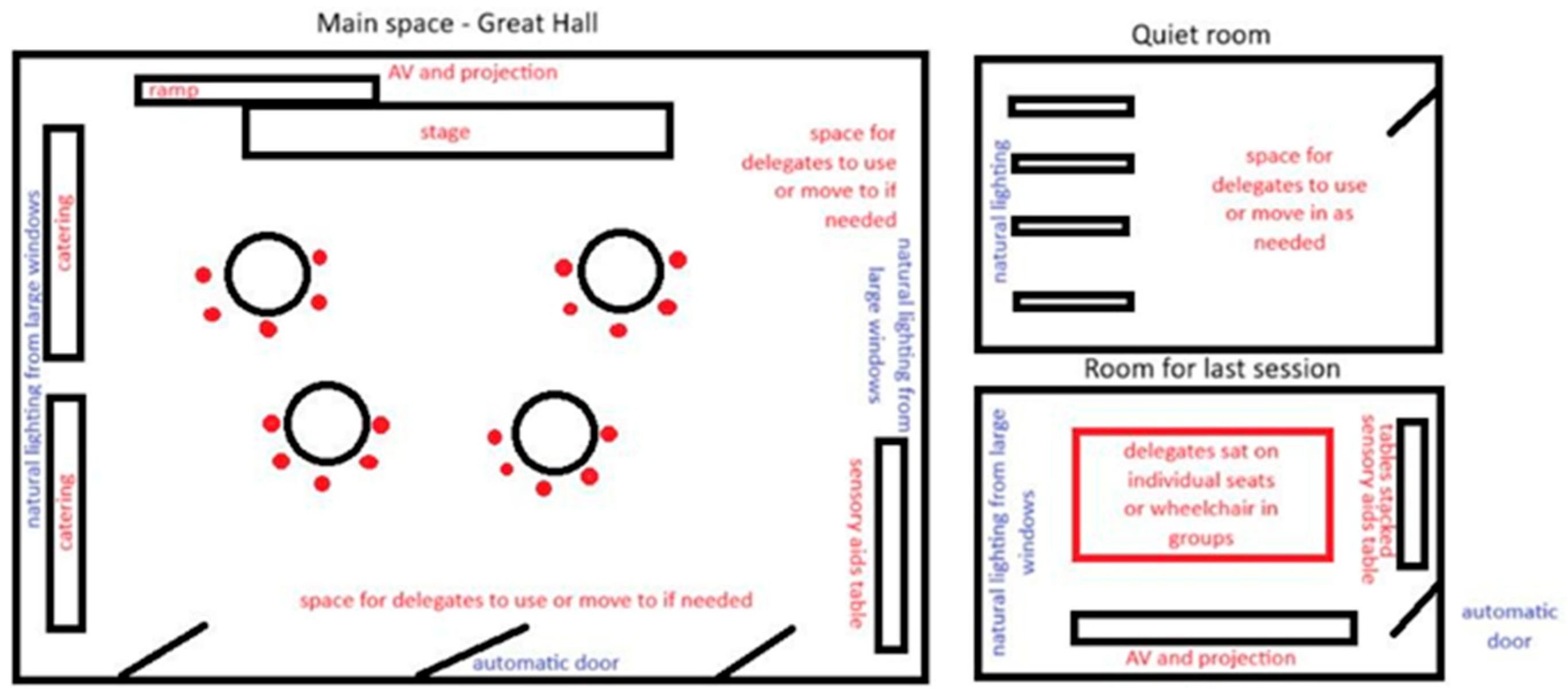

The structure of the Response Day was carefully curated to prioritize access, flexibility and care, reflecting a commitment to what some have called the practice of cripping or neuroqueering institutional time and space. Held in the spacious and accessible Great Hall at King’s College London, the venue was selected not only for its physical accessibility but also for the atmospheric openness it offered, enabling movement, rest, and participation on one’s own terms. Attendees were invited to engage with the day as they wished. Whether they needed to stim, stretch, move in and out of the room, sit in silence, or take time away entirely, the program respected diverse modes of presence. This was not simply permitted but affirmed as a scholarly and communal ethic. A figure of the layout of the spaces we used is provided in

Figure 1.

The event took place on Saturday 29 March 2025, running from 10.00 am until 4.00 pm. This decision to start later and end earlier than a typical academic conference was intentional, designed to acknowledge the fluctuating energy, travel, and health needs of many disabled and neurodivergent people. This included allowing attendees to join virtually to present or watch via an MSTeams webinar, which we had set up in advance of the day. Neurodivergent time, as

Kafer (

2013) and

Yergeau (

2018) have shown, rarely fits into institutional schedules. By designing a day with a late start, long breaks, and an early close, we enacted what crip scholar Ellen

Samuels (

2017) calls “crip time”, a form of temporal justice that acknowledges the complex temporalities of bodies and minds. Holding the event on a Saturday also enabled those working in practice-based roles, such as religious leaders, carers, SEN professionals, and community organizers, to attend without needing to take time off work. This reflected our wider commitment to thinking beyond the academic calendar and honoring the labor of knowledge-making that takes place outside university settings. The schedule of the day is provided in

Table 1.

The day began with a welcome from us, the organizers, which included a gentle icebreaker and a collaboratively framed ethics and mission statement. Rather than rigidly structured lectures, the keynote by Naomi Lawson Jacobs unfolded through a thirty-minute talk followed by a collective discussion. Jacobs’ work, which explores disabled people’s experiences in religious settings, set a powerful tone for the day’s themes.

After an extended lunch break, which allowed attendees to decompress and socialize without pressure, two afternoon panel sessions featured a range of practitioner scholars and activists. The first session included presentations from Penny Pullan, Fiona MacMillan, and Emma Swai, who joined virtually. The second session included Theo Wildcroft, Sara McHaffie (also joining remotely), and Ruth Vassilas. Their contributions spanned topics such as trauma-informed faith leadership, inclusive ritual practices, activism, and access in sacred spaces and the intersections of race, gender, and belief in neurodivergent religious lives. The final session was held in a quieter seminar room to accommodate sensory needs and featured a short film contribution from Erin Raffety, presenting God’s Brainforest, a collaborative theological resource created with disabled and neurodivergent theologians.

The day was open not only to academics but also to practitioners working in neurodiversity, disability, special educational needs, religious leadership, or at the intersections of these spaces. Activists, carers, and community organizers were also warmly welcomed. This widening of the academic frame was deliberate, grounded in the belief that meaningful conversations around neurodivergence and disability cannot be contained within traditional academic boundaries. Crucially, the hybrid nature of the event meant that delegates could decide on the day whether to attend in person or join online, offering freedom from rigid commitments that often penalize those with fluctuating health or energy levels. The registration fee was kept flat regardless of format, recognizing that online participation does not imply reduced labor or engagement. This choice destabilized the binary between “in-person” and “virtual” and offered a flexible model of conference participation aligned with feminist disability justice work (see

Hemmings 2012, p. 148). In these ways, the structure of the day enacted its own politics of access and community—not as an afterthought, but as the epistemological and ethical ground from which everything else emerged.

The Response Day unfolded exactly as we had hoped. We heard a series of brilliant contributions, but more importantly, we witnessed the formation of a community. People stayed, talked, rested, and reflected. There was openness, even when there was disagreement. There was space to be uncertain. The event became not only an opportunity to platform counter-hegemonic knowledge, but an enactment of it. Through its careful and intentional design, the day served as an example of what scholarship can become when we refuse to replicate exclusionary structures. It was a moment of praxis: gentle, radical, and transformative.

4. Organizing Within and Against: Building Radical Access Through the Response Day

The Response Day itself became a live experiment of enacting the values we outlined in our conceptual framework—namely, access-as-praxis, care-as-method, and refusal-as-possibility. While these ideas were central to our theoretical orientation, the actual organization of the event revealed the structural frictions and political negotiations that such values entail when put into practice within and across institutional settings.

Our primary aim was to curate an environment in which neurodivergent and disabled people were not only included but centered—where access was built-in rather than bolted on. This demanded intentionality across every aspect of planning, from the format and timing of sessions to the sensory set up of rooms and the structure of communication. Our design choices, such as staggered sessions, low-stimulation zones, flexible presentation formats, and facilitation styles grounded in consent and collective rhythm, were rooted in our own experiences of what exclusion feels like in academic life. These were not aesthetic choices, but deeply political and affective decisions.

Working within King’s College London, we anticipated challenges; bureaucratic rigidity, slow response times, or the need to over-explain the rationale behind our access commitments. However, what we encountered was something quite different. The internal events team responded with clarity, curiosity, and care. Once we articulated our needs clearly in the initial event documentation, these were accepted without repeated questioning or dilution. The team offered support that was collaborative rather than extractive, and decisions were made with trust and respect. This highlights what institutional support can look like when it is operationalized through active listening rather than procedural compliance.

However, our experience with another collaborating organization was far more complex. Requests for clarity around access protocols, inclusive communications, and structural considerations for the event were routinely questioned, ignored, or met with resistance, or dismissal, despite repeated explanations. This was particularly stark given that the topic of the event was disability and neurodivergence. It became clear that while there may be a discursive commitment to inclusion, the infrastructural and cultural mechanisms required to actualize that inclusion were lacking.

For one of us, who does not identify as disabled and/or neurodivergent, this became a profound moment of political awakening, not in a tokenistic sense, but through confronting how quickly and consistently access-based requests were framed as inconveniences. This resistance underscored how even well-intentioned spaces can reproduce ableist logics when inclusion is seen as accommodation rather than a radical reimagining of academic norms.

It was also a reminder that the labor of organizing inclusive events too often falls on those most affected by exclusion. As disability justice activists have long argued, the work of access—particularly when it is emotional, administrative, and pedagogical—is disproportionately carried by those living at the intersections of marginalization (

Piepzna-Samarasinha 2018). This dynamic was palpable throughout our planning process. The pressure to justify, re-explain, and sometimes fight for basic access commitments was exhausting, and the refusal to recognize our expertise—as scholars, as practitioners, as individuals embedded in activist and community work felt emblematic of a broader institutional inability to value lived knowledge.

And yet, the day itself became a space of something else entirely, a space of care, of possibility, of transformation. The room was filled with scholars, activists, and practitioners, many of whom identified as neurodivergent or disabled, who understood the stakes and shaped the space in ways that exceeded our expectations. The relationality in the room, the capacity to sit with slowness, to allow people to opt in and out, to honor embodied knowledge. These ultimately became our metrics of success.

Crucially, many participants voiced that they had never experienced an academic space quite like it. The combination of rigorous discussion, softness, autonomy, and collective rhythm created what one attendee described as “a liberating kind of structure.” In this way, the event offered a small but powerful countermodel to dominant academic forms of engagement, what Dolmage critiques as the “normate template” (2017, p. 89) of conferences that presume able-bodied, neurotypical, and socially normative participants.

We also observed a deeper tension that often goes unspoken: the siloing of disciplines. While critical disability studies has made significant advances in theorizing access, there remains a hesitation, or even discomfort, in engaging seriously with religion, belief, and spiritual practice. Likewise, while religious studies scholars are increasingly turning to embodiment, affect, and practice-based approaches, questions of access and neurodiversity remain underexplored. This disciplinary gap was evident in some of our external organizational conversations, where the intersection of religion, neurodivergence, and disability seemed illegible to institutional norms. Yet among participants, especially those with lived experience, the event’s interdisciplinary approach resonated profoundly. Many expressed a desire to carry what they had encountered, intellectually and emotionally, into their own community, faith, or research spaces.

By disciplinary siloing, we refer to the ways in which academic fields, professional sectors, and activist communities often operate in isolation, with limited dialog or shared practices (

Becher and Trowler 2001, pp. 45–46, 153–56). Such separation can constrain the development of more holistic, justice-oriented approaches. The SocRel Response Day was intentionally designed to bridge these divides, bringing academics, practitioners, and activists into shared conversations where knowledge and strategies could move more freely across boundaries.

In this sense, the Response Day did more than reflect existing conversations; it seeded new ones. It created a space where knowledge was not only exchanged, but co-produced. It modeled a different temporality, a different academic affect—one not driven by competition, performance, or cognitive speed, but by reflection, attentiveness, and mutual recognition.

Going forward, we believe the organizational model piloted in this event offers meaningful lessons for institutional practice. It requires institutions to move beyond checklist approaches to accessibility and toward a relational, 360-degree ethic of care. It demands recognition of the time, labor, and expertise that goes into creating inclusive scholarly environments. And it insists that inclusion is not an endpoint but an ongoing practice—one that must be resourced, supported, and taken seriously at all levels of academic life.

5. Wider Conversations and Challenges

Such material design decisions in organizing the Response Day mirrored deeper philosophical commitments. Our intention was to challenge the assumption that religion and neurodivergence occupy separate or non-overlapping domains. Dominant framings of neurodiversity have often been interpreted as secular or scientific, particularly by institutional religious spaces which may view disability through pastoral, moral, or even salvific lenses (

Brock and Swinton 2012;

Carter 2007). This tension was something we faced head-on. As both our own experiences and those of our speakers attested, many neurodivergent and disabled people occupy complicated relationships with religious institutions—experiencing both alienation and belonging, critique and care, and harm and healing.

There is a long-standing history of religious institutions marginalizing disabled and neurodivergent people, often under theological justifications of sin, purity, or sanctity (

Block 2002;

Creamer 2009). Yet there are also active movements within churches, mosques, synagogues, and temples, often led by disabled people themselves, that resist these narratives and work towards liberationist understandings of spiritual inclusion (see

Inclusive Church n.d. as one example). The Response Day acknowledged this tension by creating a space where it could be spoken of honestly. The discomfort around discussing religion in disability spaces (and vice versa) is culturally specific. In the UK, the residual Protestant legacy has rendered religion a “private” matter, viewed with suspicion in public discourse and often excluded from progressive or secular frameworks, including disability studies. This contrasts with the US context, where religion is more visibly enmeshed in public life. However, this privatization masks ongoing harms and precludes the critical scrutiny of religious power.

To this end, our organizing ethos drew heavily on the idea of lived religion (

McGuire 2008), which emphasizes practice, experience, and meaning making over doctrine. Feminist scholars like Meredith McGuire, Eileen Barker, and Nancy Ammerman have long argued for a shift away from institutional definitions of religion towards everyday, embodied, and situated forms of belief (

Ammerman 2014). In doing so, they paved the way for understanding how religion is experienced at the intersections of race, class, gender, and disability. Such scholarship has often been marginalized, dismissed as “soft,” or feminized—marked by its refusal to conform to dominant methodological standards. But it is precisely in this so-called messiness that we locate rigor.

Indeed, the notion of “messy methods” (

Woodhead et al. 2025) was a conceptual and ethical touchstone for us. We resisted the idea that a conference should offer tidy solutions, professionally polished outputs, or replicable “best practices.” Instead, we embraced the uncertainties, contradictions, and improvisations that inevitably arise when working within and against power. As organizers, we spent months navigating tensions around accessibility and inclusion with one of our institutional partners. This in itself became a critical site of learning: the very idea of access as non-negotiable clashed with organizational demands for clarity, budgets, and measurable outcomes. It was a live illustration of the problems that occur when inclusion is abstracted from power.

These negotiations, all enacted over email correspondence, revealed the layered and often invisible labor required to make accessibility meaningful rather than tokenistic. For example, requests for flexible formats, sensory considerations, and non-hierarchical participation structures were sometimes met with concerns about cost, scheduling, or the disruption of established event protocols. At worst these access requests were dismissed entirely and repeatedly. Documenting these exchanges, which often involved reiterating the political and ethical rationale for our choices, exposed how institutional processes can re-center efficiency over care. This became an ethnographic insight in itself, revealing the friction between organizational logics and the lived realities of those for whom access is a condition of participation rather than an optional extra.

This led us to ask: how do we practice an ethics of access that is more than performative? What does it mean to foreground epistemologies that have historically been excluded from sociology of religion—not only neurodivergent knowledges, but also those of minoritized, racialized, queer, and working-class scholars and practitioners? And crucially, how do we sustain such work when it is often precarious, underfunded, or institutionally unsupported?

In place of resolution, the Response Day offered holding spaces. The welcome was co-led with a collaboratively crafted ethics statement. The keynote was followed by dialog rather than a traditional Q&A. A dialog in this instance moves away from a traditional Q&A, i.e., the aim of the session was to host conversations, rather than the formalized structure of putting one’s hand up, asking a question, and moving onto the next person. Panelists included not only academics but also community organizers, carers, clergy, and care-experienced people. We prioritized speakers who themselves live at the intersections of disability, neurodivergence, and faith, people whose very presence posed a challenge to the disciplinary boundaries of sociology of religion.

In this way, the event was not simply a conference. It was a practice of refusal—a refusal of academic extractivism, of disciplinary purity, of normative professionalism. And it was also an invitation to sit with discomfort, to listen differently, to reimagine research not as a product but as a relationship. As scholars like

Ahmed (

2012) and

Moten and Harney (

2013) remind us, institutional critique is most powerful when it is embodied in practice. The Response Day was a glimpse of what that might look like.

6. Future Directions

The organization of this SocRel Response Day represents not only a moment of praxis but also a foundation for ongoing efforts to reshape academic and institutional event spaces. Moving forward, the lessons learned from this day are informing our approach to larger, forthcoming conferences, including the upcoming major BSA SocRel conference scheduled for the summer of 2025. Our involvement in the planning stages of this larger gathering offers an opportunity to embed principles of accessibility, inclusivity, and decolonial praxis from the outset—though it is clear this will entail significant additional labor beyond our formal roles. Yet, this work aligns with the commitments we hold to transform institutional practices, and we embrace it as part of a necessary collective effort to create genuinely equitable spaces (

Ahmed 2012;

Berila 2015).

Central to this future-facing vision is the understanding that changes designed to accommodate disabled and neurodivergent participants often produce wider benefits across diverse attendee groups. Accessibility measures such as flexible scheduling, hybrid participation options, and clear communication not only support those with disabilities or neurodivergence but also facilitate participation for carers, those with limited financial means, and individuals unfamiliar or uncomfortable with conventional academic conference norms (

Doran et al. 2024;

Walters 2020). This points to the concept of universal design as a pathway to more inclusive scholarly environments, echoing broader discourses within disability justice that emphasize intersectional and collective access (

Erevelles and Minear 2010;

Kafer 2013).

Our future event planning therefore consciously challenges the entrenched hierarchies and conventional expectations of what academic conferences “should” look like. This includes questioning rigid temporal structures, the often-exclusionary physical layouts of venues, and the implicit norms around participation and engagement. By doing so, we aim to dismantle the ‘professionalism’ boundaries that frequently silence or marginalize those who do not fit normative models of embodiment, cognition, or communication (

Goodley 2014;

Garland-Thomson 2011). Instead, we advocate for spaces that are fluid and responsive; spaces that recognize the embodied realities of all attendees and embrace a neuroqueer and crip methodological lens, which not only recognizes difference but values it as generative and transformative (

Kafer 2013;

McRuer 2006).

Moreover, our approach extends beyond practical accessibility to incorporate a decolonial ethos in the organization and curation of academic events. This involves actively interrogating the colonial legacies embedded in academic disciplines, event protocols, and institutional power dynamics, while foregrounding diverse knowledges, including those emerging from marginalized and minoritized communities (

Bhambra et al. 2018;

Tuck and Yang 2021). We recognize that intersectional accessibility cannot be divorced from such decolonial commitments, as both require a radical rethinking of who is included and how knowledge is valued and circulated.

Importantly, this approach insists that labor for accessibility and inclusivity must not fall disproportionately on those who experience marginalization. Institutional and event structures must commit to supporting this work materially and culturally, fostering collaborative organizing that shares responsibility and acknowledges expertise across lived experiences and academic scholarship (

Erevelles and Minear 2010). Our own willingness to undertake this work reflects a broader political commitment to not only envision but actively construct new possibilities for how academic communities convene and communicate.

In conclusion, the Response Day’s organization is a crucial step toward this ongoing process of transformation. It serves as both a model and a catalyst for future events that aspire to be genuinely inclusive, decolonial, and attentive to the complexities of embodiment and access. Through sustained reflection, collaboration, and resistance to normative institutional frameworks, we hope to contribute to reshaping the landscape of academic conferences into spaces that nurture belonging, innovation, and justice for all participants.

Impact of Neuroqueering

The concept of neuroqueering critically challenges dominant norms by exposing how ableism—often cloaked in euphemisms like the “cult of normalcy” (

Reynolds 2012, p. 7) or normativity—is deeply embedded in academic, religious, and social institutions. It demands that ableism be named explicitly and addressed alongside intersecting oppressions such as sexism and racism (echoing

Collins 2019;

Crenshaw 1989). Our experience organizing inclusive events highlighted how disabled and neurodivergent individuals often face bureaucratic hurdles and subtle dehumanization, reflecting systemic ableism that persists even in professional academic spaces (

Dolmage 2017;

Brown and Leigh 2018;

Botha and Cage 2022). Particularly striking was the contrast between religious studies, which tend to offer more welcoming and compassion-driven spaces, and fields like autism studies, which can be mired in pathologizing narratives (see

Milton 2014;

Botha and Cage 2022). Within religious contexts, progressive theological frameworks that center compassion, equality, and community resonate strongly with the goals of neuroqueering by validating diverse embodied and cognitive experiences (

Bhambra et al. 2018;

Wilcox 2019). Moreover, neuroqueering aligns with decolonial and abolitionist critiques, pushing beyond surface-level inclusion to disrupt and dismantle entrenched hierarchies and normative structures that limit meaningful access and participation (

Tuck and Yang 2021). This approach foregrounds the importance of lived experience and radical collaboration in reshaping academic and faith communities into genuinely inclusive spaces. Such work not only addresses immediate barriers but also builds momentum for sustained transformation, ensuring that future generations can inhabit environments where neurodiversity is embraced as a vital component of social justice and collective liberation.

7. Conclusions: Situating Neurodiversity, Decoloniality, and Inclusion Within Broader Contexts

This paper has critically examined the intersection of neurodiversity, disability, and decolonial praxis within academic and religious spaces, highlighting the transformative potential of organizing inclusive events such as the SocRel Response Day. These initiatives not only challenge entrenched hierarchies of ableism, normativity, and colonial legacies but also model new, progressive labor practices rooted in collaboration, care, and collective empowerment.

At a global level, equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts, particularly those advancing disability rights, face increasing backlash, often framed as threats to established norms and institutions. Around the world, disability rights are contested in socio-political arenas, with movements pushing for accessibility, autonomy, and recognition frequently met with resistance or co-optation (

Goodley 2014). This backlash reflects the broader discomfort societies have with disrupting normalcy and exposes how deeply ableism remains embedded in institutional cultures, including academia. Consequently, the voluntary roles within SocRel to advance equity, diversity, and inclusion are not neutral but profoundly political acts that challenge dominant power structures, making clear the activists’ positionality and commitment (

Kafer 2013).

This resistance is compounded by the neoliberal tendency to appropriate neurodiversity in ways that emphasize individual adaptability and productivity while sidelining systemic inequalities—a ‘neurodiversity lite’ that fails to fully engage with the radical social justice aims of the disability rights movement (see

Dwyer et al. 2025 for more information). Decolonial frameworks remind us that true inclusion must go beyond surface-level accommodations to dismantle intersecting systems of oppression that marginalize disabled, neurodivergent, and racialized bodies and minds.

Religious institutions, despite their complexities and contradictions, offer vital communal spaces for advancing such radical inclusion. The authority vested in religious leaders—imams, pastors, vicars—positions them as key actors in shaping attitudes toward disability and neurodivergence within faith communities. When these leaders actively embrace inclusive practices grounded in the values of equality and compassion, the impact can be profound, fostering tangible social change (

Wilcox 2019). However, this requires moving beyond vague notions of welcoming toward genuine inclusivity that embraces diverse identities, including queer and disabled individuals, in all their complexity (

Bhambra et al. 2018).

Decoloniality, as an abolitionist praxis, demands that we confront the colonial and ableist underpinnings of both academic and religious institutions. It calls for a compassionate politics that listens to marginalized voices and enacts structural transformation rather than tokenistic inclusion. This vision envisions a future where neurodiversity and disability are not merely accommodated but celebrated as integral to collective liberation, justice, and flourishing.

As advocates and scholars, the responsibility lies with us to sustain these efforts, transforming the spaces we inhabit now and paving the way for more just, accessible, and decolonized futures. This commitment is not only an intellectual project but a deeply political and ethical imperative—one that demands courage, solidarity, and a radical reimagining of what inclusion truly means.