Itinerancy and Sojourn: Bai Yuchan’s Travels as the Early Dissemination History of Daoism’s Southern School

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. From Dao-Seeking to Dao-Spreading

2.1. Periodization of Dao-Seeking and Dao-Spreading Travels

I think of the essence of the immortal way (xiandao 仙道), read the classics, seeking the mystery, but also have years to go, not to point to the return of the … paths divergent paths, do not know the tendency … Therefore, with a resolute spirit and in order to visit enlightened masters, I journeyed through all the various grotto-heavens (dongtian 洞天) and also visited places like the Fuqiu Temple on Mount Taihua. However, I did not encounter what he was ultimately seeking … Along the way to the East China Sea, I was fortunate to visit the Cuixu Xianshi and was brought back to Luofu. Sincerely begged, and then again and again, and then obtained the Dan recipe, and then knew that it was not far from the people.嘗思仙道精微,覽諸經典,尋求玄奧,亦有年矣,莫得指歸……雜徑歧途,莫知趨向……因慨然奮志,遍游諸洞天,及太華山浮丘等觀,參訪明師,終無所遇……沿至東海之濱,幸謁翠虛仙師,攜歸羅浮。心誠求之,再三再四,方得還丹口訣,始知道在目前,不遠人也。《指玄篇序》

I, by a stroke of luck from a previous life, have been able to follow the Daoist rites. I have visited various places, but I have not fully grasped the essence… I took a detour to Luofu to seek the Dao from the ancestral master, the True Man Cuixu.余以夙幸得奉沖科,遍參諸方,未盡其要……迂道過羅浮,訪道于祖師翠虛真人。《汪火師雷霆奧旨序》

In the autumn of the eighth moon during the Jiading Renshen year (1212), Cuixu Zhenren (Chen Nan) resided on Mount Luofu, where he contemplated the transient nature of existence—worldly affairs dissolving like flowing water, while the vast cosmos framed the solitary flight of a gull. In this liminal space between transcendence and immanence, he resolved to shed his mortal coil for the celestial Jade Palace, entrusting the alchemical mysteries of the golden elixir’s fiery refinement to Bai Yuchan of Qiongshan, whose spiritual insight penetrated the skeletal architecture of cosmic creation itself.嘉定壬申八月秋,翠虚道人在羅浮,眼前萬事去如水,天地何處一沙鷗。吾將蛻形歸玉闕,遂以金丹火候訣,說與瓊山白玉蟾,使之深識造化骨。

2.2. Philosophy of Travel and the Motivations Behind Dao-Spreading

In the R’yong Ji 日用記, Bai Yuchan said,Since the age of twenty-three, it seems that the forces of the six thieves have gradually become stronger, and the fire of the three corpses has burned more fiercely. I no longer have the peaceful body and mind as in the previous days自二十三歲以後,似覺六賊之兵浸盛,三屍之火愈熾,不復前日之身心太平也。《日用記》

When devoted practitioners fail to attain efficacy despite rigorous ritual practice, it is not the Dao abandoning them, but their failure to follow enlightened masters and receive orthodox methods. Others who adhere to methods yet remain unfulfilled have neglected precepts. Those truly committed must purify their hearts, reduce desires, grasp the Dao’s essence, penetrate its mysteries, widely seek qualified teachers, diligently cultivate, and properly implement the methods—only then will efficacy manifest.或有苦心學行持而不見功者,非道負人,皆奉道之士不從明師,而所受非法;或依法行持而不見功者,皆奉道之士不遵戒律,而學法不驗。有志于此者,苟能清心寡欲以明道要,以悟玄機,猶當廣求師資,勤行修煉,依法行持,何患法之不驗哉?《汪火師雷霆奧旨序》

In the royal spring (wangchun 王春) of the Bingzi 丙子 year (1216) of the Jiading 嘉定 period (1208–1224), according to the royal chronology, construction of the site commenced. The workforce was mobilised for the felling of trees for timber and the transportation of bricks. However, the commencement of this undertaking was met with considerable challenges. Shortly thereafter, Bai Yuchan departed for Mount Tiantai and Mount Yandang, leaving behind a trail of disruption. It was not until Bai Yuchan’s return that the construction of the nunnery was finally completed.歲在嘉定丙子之王春,始鳩工斫梓,僝夫運甓,然而開創之難未幾,而白玉蟾拂袖天台、雁蕩矣,玉蟾言旋,而庵始成。《武夷重建止止庵記》

On this journey, I shall depart for Mount Luofu, and upon my return, I will surely serve as the abbot of Zhizhi Hermitage 止止庵 for life.而玉蟾此去羅浮入室,回必永身以住持之。《武夷重建止止庵記》

3. Reconstruction of Key Dao-Spreading Itineraries

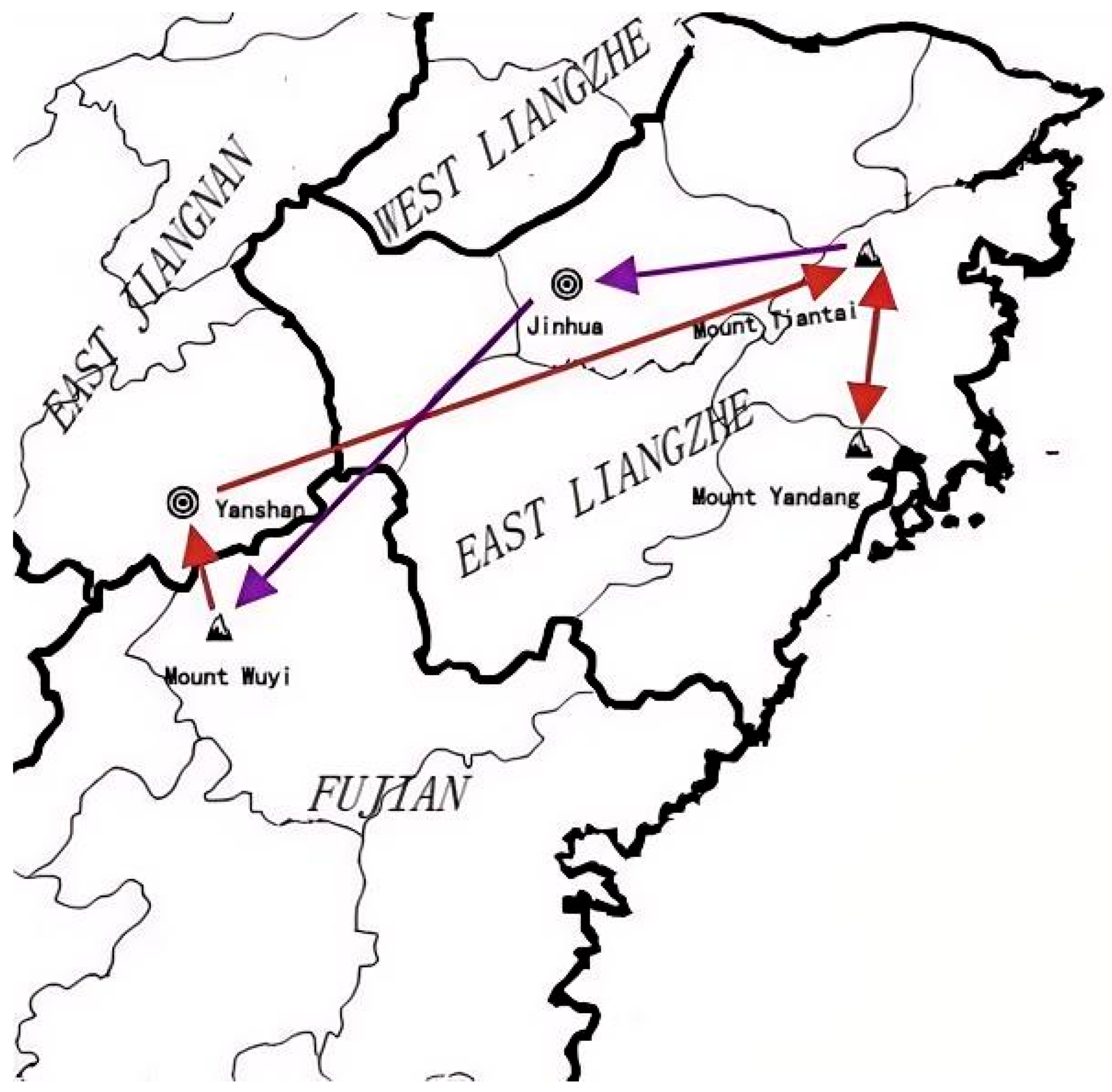

3.1. Travels to East Liangzhe Circuit in 1216

Bai Yuchan constructed a thatched hut in Mount Wuyi. However, he subsequently experienced a sudden and profound desire to travel extensively. Equipped with his walking stick and wearing suitable footwear, he embarked on his journey with ease. Before he had traversed great distances, he cast a backward glance at his former abode, and the apes were startled, and the cranes cried. In an instant, as if with a couple of sleeve-waves, he found himself in Yanshan County without even realizing it. … Two days after the Rain Water solar term (yushui 雨水) in the Bingzi year of the Jiading period, I picked up a writing brush and wrote down the aforementioned content.白玉蟾結茅于武夷,偶一日,起湖海之興,杖屨飄飄,未數舉步,回首舊廬,猿驚鶴唳,一二揚袂間,不覺已鉛山矣……嘉定丙子雨水後兩日,援筆為記云。《駐雲堂記》

Bai Yuchan happened to come to Jinhua Cave. The moment I saw him, I felt as if we were old friends. I invited him back to my humble abode, and through leisurely conversations, I began to understand his inner thoughts.偶來金華洞,森一見如故人,延歸蝸舍,從容扣之,始覺其方寸。《跋修仙辨惑論》

The older man has a floating home in Jinhua, which was the former residence of his ancestor, the assistant minister翁有金華之浮家,即其先侍郎之故廬也。《懶翁齋賦》

White clouds accompany me as I climb to Tiantai,Then follow me on the return journey towards Jinhua.The Phoenix-perching Pavilion fails to detain me,At the foot of Mount Wuyi, wild apes wail in pain.白雲隨我上天台,又趁金華路上回。棲鳳亭中留不住,武夷山下野猿哀。《曲肱詩》

1. Full-time officials who actually handled administrative duties;2. Part-time officials who largely did not participate in daily affairs;3. Nominal officials with no involvement in any affairs whatsoever.

Abruptly, a crane-like messenger presented a beautiful letter, ordering me to return for a meeting in Mount Wuyi. I was in a difficult situation, almost facing the risk of sacrificing my life on Mount Longhu. Without wings to fly, I endured the hardships of traveling in the wind and rain, rushing back to serve you忽承鶴使擲示鸞箋,戒回會于武夷。有身被沮溺,將捐軀于龍虎。無翅可飛行,雨臥風餐,奔歸侍下。《謝仙師寄書詞》

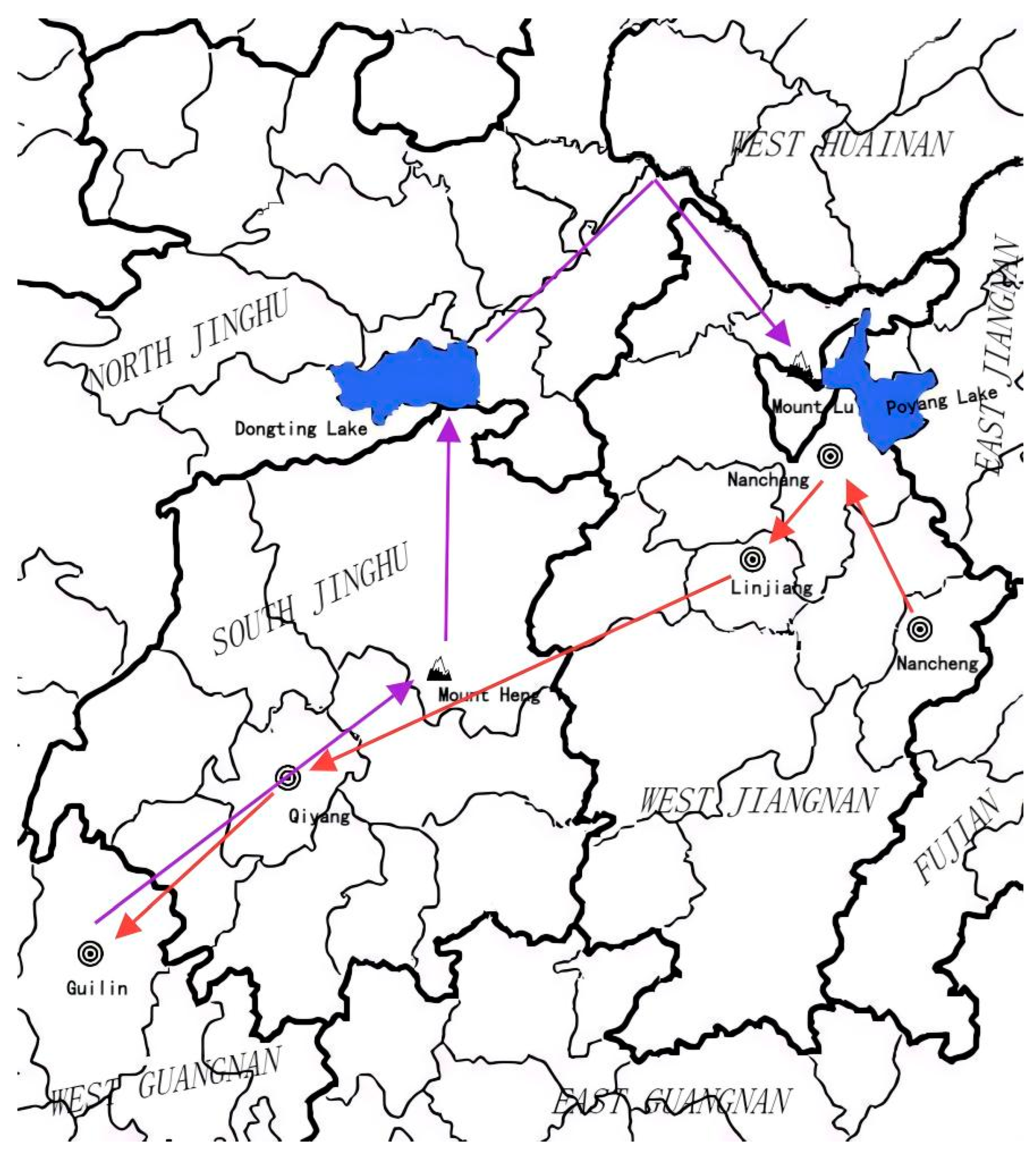

3.2. Travels to West Jiangnan Circuit in 1218

According to Yongcuiting ji 湧翠亭記,In the Wuyin year of the Jiading period (1218), Bai Yuchan of Qiongshan carried his sword through Yulong, visited Fuchuan, and passed through Wucheng.嘉定戊寅,瓊山白玉蟾,攜劍過玉隆,訪富川,道經武城。《湧翠亭記》

Poets and recluses, when appraising the landscapes and discussing the charm of the wind and the moon, all say: “The south of the Yangtze River is a treasure trove of landscapes, and Jiangxi is a haven of the charm of the wind and the moon.”騷翁逸人,品藻山水,平章風月,皆曰:江南山水窟,江西風月窩

“During the Jiading period, Bai Yuchan traversed from Fuchuan to Wuning 武甯, scaled Mount Liu 柳山 and composed the Yongcuiting Ji, and ascended Mount Jiugong and inscribed the Zhenmutang Ji 真牧堂記”嘉定中由富川過武甯,登柳山作《湧翠亭記》,登九宮山作《真牧堂記》

I rested on the west of Wucheng… The mountain that soars like a crane dancing in the sky and meanders like a dragon veiled in mist is Mount Liu. With white water chestnuts and red knotweeds, purple bamboos and pale sands, fish swimming in the blue waves, gulls lying under the bright moon, a vast expanse of shimmering waters like glass, and numerous shuttling boats, the river that is as elegant as a fairy’s shawl in the rosy clouds and as clear as the silk of the River-Goddess Xiang 湘娥 is the Xiu River 修江.憩武城之西……翼然如舞天之鶴,婉然如罩煙之龍者,柳山也。白蘋紅蓼,紫竹蒼沙,魚浮碧波,鷗臥素月,琉璃萬頃,舳艫千梭,窈然如霞姬之帔,湛然如湘娥之毅者,修江也

He departed from Qi’an 齊安 and arrived in Fuchuan on the first day of the fourth lunar month. After staying there for seven days, he left and reached Mount Lu 廬山 on the tenth day.先生去齊安,以四月一日至富川,以七日去,以十日至廬山。《東坡先生祠堂記》

From Fuchuan, passing through Qichun, I was going to Wuling.自富川,過蘄春,將之武陵。《贈日者》

The Fuchuan Zhi consists of six volumes, written by Pan Tingli from Kuocang, a professor at the military-run school. The local prefect was Zhao Shanxuan, and the work was completed in the fourth year of the Shaoxi period (1193). The administrative center of the army was Yongxing, which was originally Fuchuan County, thus explaining the nomenclature.《富川志》六卷,軍學教授括蒼潘廷立撰。太守趙善宣,紹熙四年也。軍治永興,本富川縣,故名。《直齋書錄解題》

“The Fuchuan Zhi consists of three volumes. Compiled by Li Shoupeng, the prefect in the Jiashen year of the Jiading period (1224).《富川志》三卷,右嘉定甲申守李壽鵬修。《郡齋讀書志. 讀書附志》

In the spring of Wuyin year (1218), Bai Yuchan visited Mount Xi. When an imperial decree ordered a ritual (jianjiao 建醮) at Yulong Palace, he initially declined to participate. Envoys intercepted him at the palace gate, compelling him to preside over the state ceremony, which was witnessed by a massive crowd. He was later invited to lead another imperial ritual at Ruiqing Palace on Mount Jiugong.戊寅春,遊西山,適降御香建醮於玉隆宮,先生避之,使者督宮門力挽先生回,為國升坐,觀者如堵。又邀先生詣九宮山瑞慶宮主國醮。《海瓊玉蟾先生事實》

Like a solitary phoenix flying without a fixed abode, you have journeyed to Mount Tiantai, visited Mount Lu 廬山, and now you have passed through Sanshan 三山. It is no different from being in Guangdong in the morning and Wuzhou in the evening… These days, at the transition between autumn and winter, the weather is changeable, with temperatures fluctuating between cold and warm… I, Chen, am seventy-five years old.一梧孤飛無定處,走天台,遊廬阜,今又過三山,何異朝粵暮梧也。……日來秋冬之初,寒燠不定。……諶行年七十有五。《待制李侍郎書》

3.3. Travels to West Guangnan Circuit in 1223–1224

Subsequently, Ziqing Bai Yuchan traversed Bagui, navigated the Sanxiang (三湘, Hunan) waterways, sailed along the Mian River (mianjiang 沔江, the ancient alternative names for the Yangtze River), and ascended Mount Lu.已而紫清白玉蟾道八桂,航三湘,浮沔江,歷廬阜。《龍沙仙會閣記》

After spending extensive time with my Daoist master by the seaside, I departed Mount Luofu and entered Mount Wuyi, embarking on an itinerary through the sacred peaks of Jiangxi. I traversed Hongya Cliff, sailed past Yanglan-Zuoli, sojourned in Qiantang, then proceeded via Gusu to Mount Lu. I purified my spirit by the waters of Dongting Lake, gazed upon Mount Jiuyi, and recently wandered with my ritual sword between southern Hunan and northern Guangxi. My sail unfurled across Dongting’s expanse, while the Jiuyi peaks loomed through distant mists, their twenty-four cliffs piercing the heavens. Between Guizhong and the surging Sanxiang rivers, he descended the Jiujiang region, where dragon-like echoes and tiger-like roars reverberated. The moon wheeled above Mount Yusi, as dew descended before the Mount Gezao altars.後從方外師海邊甚久,出羅浮,入武夷,始行江西閣笥間;過洪崖,下揚瀾左蠡,客錢塘,複由姑蘇而廬山;濯洞庭,眺九嶷,近方攜劍于湘南桂北……揚帆洞庭之上,回顧九嶷,在冥茫二十四岩屹。桂中、三湘舞澎湃。下九江,倏龍吟,忽虎嘯。月自玉笥雲頭轉,露從閣皂山前下。《黎怡庵詩集序》

Bai Yuchan set out from Guilin via Mount Heng, arrived at the western bank of the Yangtze River (Jiangxi), then climbed the rugged Chunyan to pay homage.白玉蟾從桂林道衡山,下大江以西,登孱顏而拜之。《麻姑賦》

I first visited the reclusive scholar Jiang Jifu six years prior.清逸居士蔣君吉甫,余六年之先訪之矣。

On the first day of the mid-autumn festival in the Guiwei year of the Jiading era (1223), I journeyed with Huang Tiangu from Xu to Yu, composing these linked verses aboard our boat.嘉定癸未仲秋之朔,偕黃天谷道盱而渝,舟中聯句。

In ancient times, the Great Immortal Fuqiu and the Perfected Lords Wang and Guo came from the Southern Sacred Peak (南嶽, Mount Heng), passed through Yuzhang (豫章, Nanchang), crossed Wei Pavilion (魏亭), and lodged at Mount Ma.昔浮丘大仙與王、郭二真君來,自南嶽過豫章,越魏亭,邸麻山。

4. Sojourn and Community Interactions During Dao-Spreading Travels

4.1. Regional Sojourn and Revisit

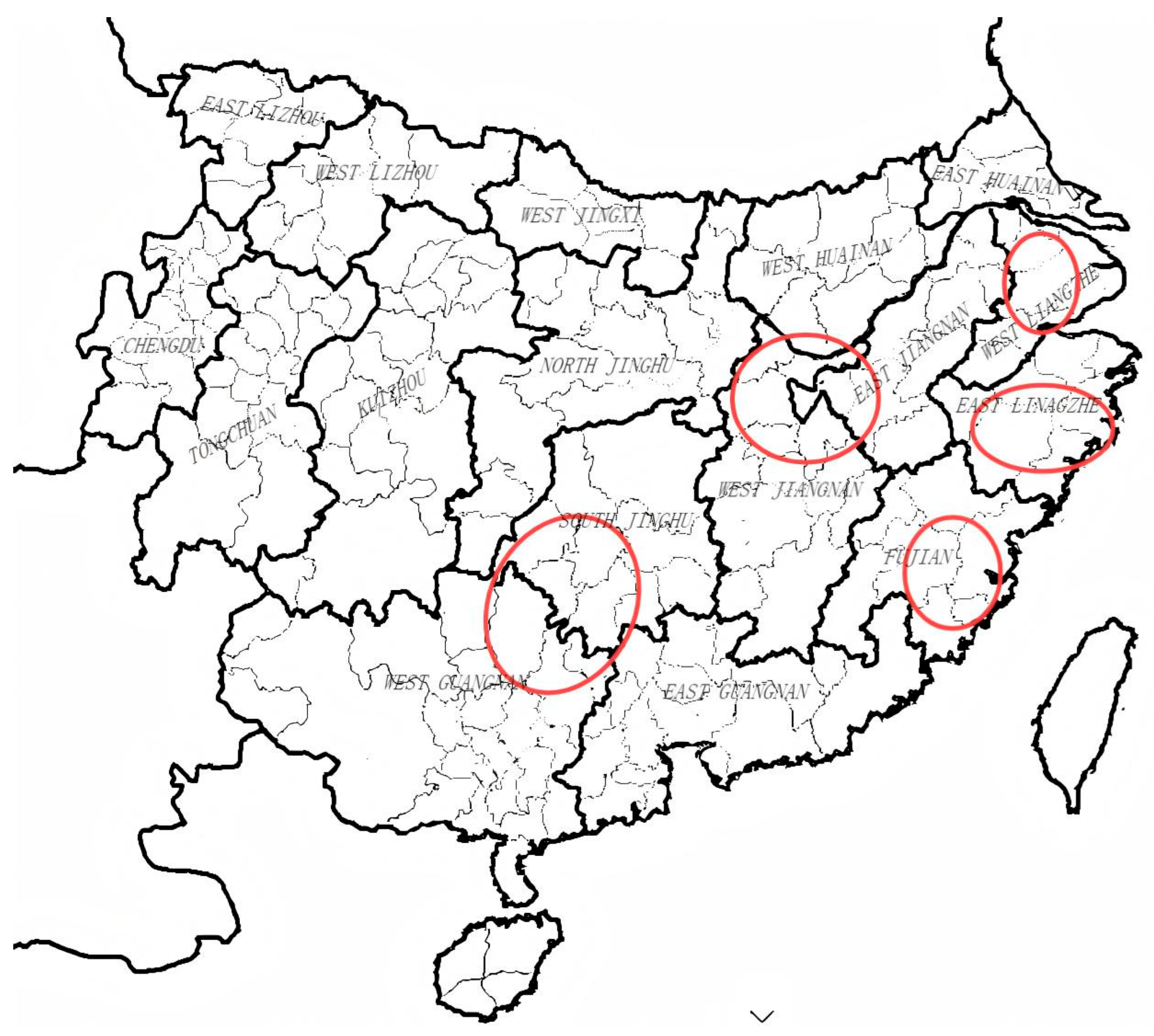

- 1216: Departing in the first lunar month, he traveled to Mount Tiantai (in Taizhou 台州) and Mount Yandang (in Wenzhou 温州), with a stop at Jinhua (in Wuzhou 婺州). These three adjacent prefectures lie within the East Liangzhe Circuit. Residing in this region until his departure around the Zhongyuan Festival in the seventh lunar month, his stay spanned five or six months.

- 1217: Arriving in Fuzhou 福州 in spring, he did not depart from Fuzhou 福州 until the ninth lunar month, staying in Fuzhou and its surrounding areas for at least half a year.

- 1218: From spring to the tenth lunar month, he journeyed to Mount Xi (in Longxing Fu), Mount Jiugong (in Xingguo Jun), and Mount Lu (in Nankang Jun). These sites, clustered along the border of the West Jiangnan Circuit and the East Jiangnan Circuit 江南東路, were geographically linked, with Bai Yuchan’s sojourn in the area lasting over six months.

- 1221: In the third lunar month, he traveled to Pingjiang Fu 平江府, on the eastern shore of Tai Lake 太湖. Thereafter, he visited Huzhou 湖州 on the western shore of the lake. The two places were adjacent, and both belonged to the West Liangzhe Circuit 两浙西路. Departing only at the end of the year, he stayed in this area for more than six months.

- 1223–1224: Traveling from the eighth lunar month to the following summer in Xiangnan-Guibei (湘南桂北, southern Hunan and northern Guangxi), his journey, accounting for transit time, likely lasted approximately six months.

On the 21st day of the tenth lunar month, Bai, an older man from Qiongshan, sent a letter to Peng Si, the true Daoist scholar from Helin 鶴林 in Fuzhou 福州, at his residence: This spring, I went to Jiangzhou, travelled through Xingguo Jun, reached Yueyang, returned to Yuzhang, passed by Fuzhou 撫州, paid a visit to Mount Huagai, went down to Linjiang Jun, took the route via Raozhou and Xinzhou, and then headed to the East Zhejiang Road (zhedong 浙東). On the first day of the eighth lunar month, I arrived at the imperial capital (xingzai行在means Lin’an臨安), then travelled to Shaoxing, passed through Qingyuan Fu, and returned to Lin’an again… I intend to go to Tiantai.十月二十一日,瓊山老叟白某致書福州鶴林真士彭卿治所:今春到江州,行興國軍,如岳陽,回豫章,過撫州,謁華蓋山,下臨江軍,取道饒信而浙東。以八月一日詣行在,複遊紹興,過慶元府,再歸臨安……欲往天台.

4.2. Outsiders’ Community Interactions

The Gao’an in Yongxing County, Xingguo, and the Yuanshan in Huangmei County, Qizhou, had their respective former proprietors: Li Jiansun and Xiang Zhida. The rest were all subordinate counties of Jiangzhou Prefecture: Cuilu in Hukou County, Wan’an in De’an County, Fuxing in Pengze County, and Zhaochen in Ruichang County, whose former proprietors were Zhou Shu, Hu Rong, and Lü Shishan, as well as Qi Yongnian recorded on the stele as serving as Assistant Administrator (tongzhi 同知) of Fuzhou Lu.惟高岸居興國之永興,元山居蘄之黄梅,其故主則厲堅孫、項至大。餘皆江之屬縣:翠麓湖口、萬安德安、福興彭澤、趙陳瑞昌,其主周恕、胡榮、吕師山,則碑福州路同知者與齊永年。《太平宮新莊記》

According to Bai Yuchan’s Taiping Xingguo Gong Ji 太平興國宮記,On the Qingming Festival of the Jiading Wuyin year (1218), Bai Yuchan, a Daoist from the Linghuo Tongjing Grotto-Heaven in Fuzhou, approached the Terrace of the Nine Celestial Messengers with sleeves billowing incense in reverence.皇宋嘉定戊寅清明,福州靈霍童景洞天羽人白玉蟾,袂香趨敬九天御史台下。《太平興國宮記》

The Master of Chanxi Unseal the ritual wine vessel, a hundred cups leave me muddled as sludge. Ancient ink adorns the walls of Cuilu Pavilion, and a mournful spring ode echoes through the pine-framed windows.蟾溪主人拆社甕,百杯醉我爛如泥。翠麓軒壁凝古墨,一闋松窗傷春詞。《周唐輔仙居莊作》

During my tenure holding authority over judicial affairs in Jiangnan East, we shared a profound connection south of Mount Lu. When I later served at the temple granary, he occasionally visited me by the Tiao River.余持節憲江東之日,嘗相契于廬山之陽。及其祠廩也,時過我於苕溪之上。《松風集序》

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Peng Zhu emphasized the number “three” in his naming because these historical records are taken from three distinct chapters in the Shenxian Tongjian 神仙通鑒: Volume 20, Section 5, “Daoxue xing daru qushi, shenwei xian pankou wanghun” 道學興大儒去世,神威顯叛寇亡魂, Volume 20, Section 6, “Qianhou yunyou yuchan ku, jiurou shentong daoji dian” 前後雲遊玉蟾苦,酒肉神通道濟顛, and Volume 22, Section 5, “Yindi jing pei xindi ben, xiaocheng ji zhu dacheng ji”陰地經培心地本,小成集築大成基. |

| 2 | At present, in the academic circle, there are already six viewpoints regarding the birth year of Bai Yuchan, namely 1134, 1142, 1149, 1153, 1187, and 1194. For the sake of conciseness, no further details will be given here. |

| 3 | This study employs the Lidai Zhongxi Duizhao Jieqi Ruelue Meiri Libiao 歷代中西對照節氣儒略每日曆表created by Jian Jinsong簡錦松 to determine the date of the Rain Water solar term during the Jiading Bingzi year (1216 CE). Even if minor discrepancies of one or two days exist in the calculation, such variations would not substantively impact the author’s conclusions. The calendar database is publicly accessible at https://see.org.tw/calendar. accessed on 21 October 2024. |

| 4 | Regarding the estimation of the distance between Cloud Dwelling Hall and Zhizhi Hermitage. Huanyu Tongzhi 寰宇通志 records that “Zhuyuntang is two li east of the seat of Yanshan County. Bai Yuchan recorded it in the Song Dynasty” (X. Chen and Peng 2014, chap. 43, p. 6). (Jiajing) Yanshan Xianzhi (嘉靖) 鉛山縣誌 states that “It is located east of the county seat, and was also known as Zhuyunlou. It had been abandoned for a long time and was recorded by Bai Yuchan” (Fei 1990, chap. 7, p. 7). Either the Cloud Dwelling Hall still existed during the Jingtai period, or Huanyu Tongzhi simply followed previous records. From the establishment of Yanshan County in the Southern Tang Dynasty (937–975) until before the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the administrative seat of the county was always located in Yongping Town 永平鎮. The estimation of the distance between the two places is based on present-day Yongping Town, Yanshan County. |

| 5 | In 1218, on the Double Ninth Festival (Chongyang jie 重陽節), Liu Yuanchang recorded, “My master, Lord Haiqiong, travelled between Mount Lu. In the spring of the Wuyin 戊寅 year of the Jiading period (1218), he sent a letter to arrange a meeting in Wuyi Mountain. Due to my official duties in the military office, I went to the capital in the summer and returned in the autumn. I searched for him by boat, but he was nowhere to be found” (Bai 1988a, p. 117). Bai Yuchan did not appear at the agreed-upon time and place with Liu Yuanchang. |

| 6 | In a letter written to Peng Si in the spring of 1223, Bai Yuchan made an appointment, saying, “We will surely meet again at the end of autumn and the beginning of winter” (Bai 1988a, p. 138). However, according to Liu Shouzheng’s inference, Bai Yuchan did not meet Peng Si in the second half of 1223 (S. Liu 2012, p. 55). |

References

- Bai, Yuchan 白玉蟾. 1988a. Haiqiong Bai Zhenren Yulu 海瓊白真人語錄 [Sayings of True Person Bai, Haiqiong]. In Daozang 道藏 [The Taoist Canon]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe, vol. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Yuchan 白玉蟾. 1988b. Yulong Ji 玉隆集 [Collected Works of Yulong]. In Xiuzhen Shishu·修真十書 [Ten Books on Cultivating Perfection]. Daozang 道藏 [The Taoist Canon]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Yuchan 白玉蟾. 1988c. Gaoshang Jingxiao Sanwu Hunhe Dutian Dalei Langshu 高上景霄三五混合都天大雷琅書 [The Jade Book of the Great Thunder of the Universal Heaven, on the Three-Five Unity of the High and Exalted Jingxiao]. In Daofa Huiyuan 道法會元 [Collection of Daoist Rituals]. Daozang 道藏 [The Taoist Canon]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe, vol. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Yuchan 白玉蟾. 1988d. Daofa Jiuyao 道法九要 [Nine Essentials of Daoist Rituals]. In Daofa Huiyuan 道法會元 [Collection of Daoist Rituals]. Daozang 道藏 [The Taoist Canon]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe, vol. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Yuchan 白玉蟾. 1988e. Jingyu Xuanwen靜余玄問 [Profound Inquiries in Quiet Leisure]. In Daozang 道藏 [The Taoist Canon]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe, vol. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Yuchan 白玉蟾. 2000. Bai Zhenren Ji 白真人集 [Collected Works of True Person Bai]. In Daozang Jinghua 道藏精華 [Essence of the Taoist Canon]. Edited by Tianshi Xiao 萧天石. Xinbei: Ziyou Chubanshe, vol. 10.2. [Google Scholar]

- Berling, Judith A. 1993. Channels of Connection in Sung Religion: The Case of Pai Yü–ch’an. In Religion and Society in T’ang and Sung China. Edited by Patricia Buckley Ebrey and Peter N. Gregory. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jinfeng 陳金鳳. 2013. Bai Yuchan Jiangxi Daojiao Huodong Kaoshu 白玉蟾江西道教活動考述 [On Bai Yuchan’s Taoist Activities]. Huaqiao Daxue Xuebao (Zhexue Shehui Kexue Ban) 華僑大學學報 (哲學社會科學版) 1: 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Kechang 陳克昌. 2004. Magu Ji麻姑集 [Magu Collection]. In Zhongguo Daoguanzhi Congkan Xubian中國道觀志叢刊续编 [Supplementary Series of the Collection of Chinese Daoist Temple Records]. Yangzhou: Guangling Shushe, vol. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Nan 陳楠. 1988. Cuixu Pain 翠虛篇[Cuixu Treatise]. In Daozang 道藏 [The Taoist Canon]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe, vol. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xun 陳循, and Shi Peng 彭時. 2014. Huanyu Tongzhi 寰宇通志 [Universal Gazetteer]. In Zhonghua Zaizao Shanben·Ming Qing Bian 中華再造善本·明清編 [Zhonghua Reconstructed Rare Books·Ming-Qing Series]. Beijing: Guojia Tushuguan Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Zhensun 陳振孫. 1987. Zhizhai Shulu Jieti 直齋書錄解題 [Zhizhai’s Annotated Bibliography of Books]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Baozhang 方寳璋, and Hongtao Yu 于洪濤. 2015. Bai Yuchan Jiaoyou Kaolun 白玉蟾交友考论 [Research on Social Intercourse of Bai Yuchan]. Shijie Zongjiao Yanjiu 世界宗教研究 3: 104–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Cai 費宷. 1990. (Jiajing) Qian Shan Xianzhi(嘉靖)鉛山縣誌 [(Jiajing Reign Period) Yanshan County Gazetteer]. In Tianyi Ge Cang Mingdai Fangzhi Xuankan Xubian天一閣藏明代方志選刊續編 [Supplementary Series of Selected Ming Dynasty Local Gazetteers in the Tianyi Ge Collection]. Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Guanghong 馮廣宏. 2015. Bai Yuchan Xingcang Kao 白玉蟾行藏考 [An Investigation into Bai Yuchan’s Whereabouts and Life Experiences]. Wenshi Zazhi 文史雜誌 5: 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Xieding 傅燮鼎. 2000. Jiugong Shanzhi 九宮山志 [Records of Mount Jiugong]. In Zhongguo Daoguanzhi Congkan 中國道觀志叢刊 [Collection of Chinese Daoist Temple Records]. Yangzhou: Guangling Shushe, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Fudan University and Harvard University Institute. 2014. China Historical Geographic Information System. Available online: https://maps.cga.harvard.edu/tgaz/placename/hvd_41121 (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Gai, Jianmin 蓋建民. 2013a. Daojiao Jindan Pai Nanzong Kaolun: Daopai, Lishi, Wenxian Yu Sixiang Zonghe Yanjiu 道教金丹派南宗考論:道派、歷史、文獻與思想綜合研究 [A Study on the Southern Lineage of the Golden Elixir—Its Schools History, Documents and Thoughts]. Beijing: Shehui Kexue Wenxian Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Gai, Jianmin 蓋建民. 2013b. Dongyue Xinyang Yu Bai Yuchan Daojiao Jindanpai Nan Zong Lüekao—Yi Fuzhou, Ningde Diyu Wei Zhongxin 東嶽信仰與白玉蟾道教金丹派南宗略考—以福州、寧德地域為中心 [A Brief Examination of Dongyue Beliefs and Bai Yuchan’s South-School of Inner Alchemy Taoism—Centered on Fuzhou and Ningde Regions]. Shehui Kexue Yanjiu 社會科學研究 6: 121–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gai, Jianmin 蓋建民. 2014. Bai Yuchan Daojiao Jindanpai Nan Zong Yu Tianshi Dao Guanxi Xintan 白玉蟾道教金丹派南宗與天師道關係新探 [Discuss The Relationship about Bai Yuchan’s Jindan Schools of South Taoism with Tianshi Taoism]. Hunan Daxue Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) 湖南大學學報 (社會科學版) 4: 103–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gai, Jianmin 蓋建民. 2016. Bai Yuchan Jindanpai Nan Zong Yu Zhu Xi Lixue Guanxi Xinkao 白玉蟾金丹派南宗與朱熹理學關係新考 [New Probe on the Relationship between Bai Yuchan’s Southern Taoist Jindan School and ZHU Xi’s Rational Philosophy in the Song Dynasty]. Hubei Daxue Xuebao (Zhexue Shehui Kexue Ban) 湖北大學學報 (哲學社會科學版) 2: 45–55+160. [Google Scholar]

- Gai, Jianmin 蓋建民. 2019. Bai Yuchan Yu Shi Shijian Biankao 白玉蟾遇師時間辨考 [A Study of the Time of Bai Yuchan’s Meeting His Master]. Shijie Zongjiao Yanjiu 世界宗教研究 2: 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Wu 郭武. 2006. Bai Yuchan Zai Xishan de Huodong ji qi Dui Jingmingdao de Yingxiang 白玉蟾在西山的活動及其對淨明道的影響 [Bai Yuchan’s Activities in Xishan and Their Influence on Jingming Dao]. Zhongguo Daojiao 中國道教 2: 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Wu 郭武. 2008. Jingming Dao Yu Jindanpai Nan Zong de Guanxi 淨明道與金丹派南宗的關係 [The Relationship Between Jingming Dao and the Golden Elixir School Southern Sect]. In Tiantai Shan Ji Zhejiang Qu Yu Daojiao Guo Ji Xue Shu Yan Tao Hui Lun Wen Ji 天台山暨浙江區域道教國際學術研討會論文集 [Proceedings of the International Academic Symposium on Tiantai Mountain and Zhejiang Regional Daoism]. Edited by Xiaoming Lian. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Ancient Books Publishing House, pp. 180–86. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Yongfeng 黃永鋒, and Baozhang Fang 方寶璋. 2012. Bai Yuchan Huodong Quyu Kao 白玉蟾活動區域考 [Textual Research on Bai Yuchan’s Active Areas]. Shijie Zongjiao Yanjiu 世界宗教研究 6: 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Xun 焦循. 1987. Mengzi Zhengyi 孟子正義 [Critical Exposition of the Mencius]. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Zongrong 蘭宗榮. 2008. Bai Yuchan Wuyi Shan Xingji Kaolun 白玉蟾武夷山行跡考論 [An Investigation into Bai Yuchan’s Itineraries in Wuyi Mountain]. Master’s Dissertation, Shandong University, Jinan, China. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fengmao 李豐楙. 1997. Xu Xun Yu Sa Shoujian—Deng Zhimo Daojiao Xiaoshuo Yanjiu 許遜與薩守堅—鄧志謨道教小說研究 [Xu Xun and Sa Shoujian: A Study of Deng Zhimo’s Daoist Novels]. Taibei: Taiwan Xuesheng Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yuanguo 李遠國. 2003. Shenxiao Leifa: Daojiao Shenxiaopai Yange Yu Sixiang 神霄雷法:道教神霄派沿革與思想 [Shenxiao Thunder Magic: Evolution and Thought of the Daoist Shenxiao School]. Chengdu: Sichuan Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Liang 劉亮. 2013a. Bai Yuchan Shengzu Nian Xinzheng 白玉蟾生卒年新證 [A New Textual Study of the Date of Birth and Death of Baiyuchan]. Wenxue Yichan 文學遺產 3: 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Liang 劉亮. 2013b. Bai Yuchan Zaonian Ji Jiading, Baoqing Nianjian Xingzong Kao 白玉蟾早年及嘉定、寶慶年間行蹤考 [A Textual Research into Bai Yuchan’s Tracks in His Early Times and From Jiading to Baoqing Period]. Hainan Daxue Xuebao (Renwen Shehui Kexue Ban) 海南大學學報 (人文社會科學版) 5: 118–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shouzheng 劉守政. 2012. Bai Yuchan Daojiao Sixiang Yanjiu 白玉蟾道教思想研究 [A study of Bai Yuchan’s Taoism Thought]. Doctoral Dissertation, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Guolong 盧國龍. 2003. Zhuo Shi Jia Gongzi Chan Gong Zhe Xian Ren—Bai Yuchan de Qiu Dao Zhi Lü ji Gui Yin Zhi Xiang 濁世佳公子蟾宮謫仙人—白玉蟾的求道之旅及歸隱之鄉 [A Fine Gentleman in a Turbid World, an Immortal Banished from the Moon Palace: Bai Yuchan’s Journey of Seeking the Dao and His Hometown of Seclusion]. Zhongguo Daojiao 中國道教 4: 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Zengxiang 陸增祥. 2002. Baqiongshi Jinshi Buzheng 八瓊室金石補正 [Baqiongshi Supplements and Corrections to Inscriptions on Metal and Stone]. In Xuxiu Siku Quanshu 續修四庫全書 [Sequel to the Siku Quanshu]. Edited by Tinglong Gu 顾廷龙 and Xuancong Fu 傅璇琮. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, vol. 898. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Zhengming 羅爭鳴. 2021. Zhang Boduan Jiqi “Wuzhen Pian” Zhu Wenti de Zai Jiantao 張伯端及其《悟真篇》諸問題的再檢討 [Discussion on Zhang Boduan’s Life and the Completion, Theme and ReligiousLiterature Significance of Wuzhen Pian]. Zhongguo Wenxue Yanjiu 中國文學研究 2: 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, Strickmann. 1980. History, Anthropology, and Chinese Religion [Review of The Teachings of Taoist Master Chuang, by Michael. Saso]. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 40: 201–48. [Google Scholar]

- Miyakawa, Hisayuki 宮川尚志. 1978. Nanso no Doshi Haku Gyozen no jiseki. 南宋の道士白玉蟾の事蹟. In Tōyoshi ronshu Uchida Gimpū Hakushi Shōju Kinen 東洋史論集:內田吟風博士頌壽紀念. Kyoto: Dohosha同朋社, pp. 499–517. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Qi 孫齊. 2014. Tangqian Daoguan Yanjiu 唐前道觀研究 [A Study of the Daoist Monasteriesin pre-Tang Dynasties]. Doctoral Dissertation, Shandong University, Jinan, China. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Takeo 鈴木健郎. 2012. Bai Yuchan to Daojiao Shengdi 白玉蟾と道教聖地. Dongfang Zongjiao 東方宗教 120: 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Umehara, Kaoru 梅原郁. 1986. Civil and military officials in the Sung: The chi-lu-kuan system. Acta Asiatica 50: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Shengduo 汪聖鐸. 1998. Guanyu Songdai Cilu Zhidu de Jige Wenti 關於宋代祠祿制度的幾個問題 [Several Issues Concerning the Sacrificial Office System in the Song Dynasty]. Zhongguo Shi Yanjiu 中國史研究 4: 107–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Wenqing 王文卿. 1988. Huoshi Wangzhenjun Leiting Aozhi火師汪真君雷霆奧旨 [The Profound Principles of Thunder and Lightning by Lord Wang, Master of Fire]. In Daofa Huiyuan 道法會元 [Collection of Daoist Rituals]. Daozang 道藏 [The Taoist Canon]. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe, vol. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhi 王質. 1985. Xueshan Ji 雪山集 [Collected Works of Xueshan]. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Zheng 魏徵. 1982. Sui Shu 隋書 [Sui History]. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Guofu 吳國富. 2011. Lushan Daojiao Shi 廬山道教史 [A History of Daoism on Mount Lu]. Nanchang: Jiangxi Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Dao 徐道. 1995. Shenxian Tongjian 神仙通鑒 [Comprehensive Mirror of Immortals]. Shenyang: Liaoning Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Yiwen 葉義問. 1988. Lushan Taipingxingguogong Caifangzhenjun Shishi廬山太平興國宮採訪真君事實 [Facts about Cai Fang Zhenjun at Taiping Xingguo Palace on Mount Lu]. In Daozang 道藏. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian, Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe, vol. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Yokote, Yutaka 橫手裕. 1996. Haku Gyokusen to Nansō Kōnan dōkyō 白玉蟾と南宋江南道敎. Tōhō gakuhō 東方學報 68: 77–182. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Jinlan. 2007a. Bai Yuchan Jiaoyou Lunkao—Dan Dao Nan Zong Chuandao Duixiang Fenxi 白玉蟾交遊論考—丹道南宗傳道对象分析 [Evaluation of Bai Yuchan’s Amity—Predicatory of Inner Alchemy of SouthernLineage in Song Dynasty]. Shijie Zongjiao Xuekan 世界宗教學刊 10: 251–354. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Jinlan 曾金蘭. 2007b. Song Dai Dan Dao Nan Zong Fazhan Shi Yanjiu—Yi Zhang Boduan Yu Bai Yuchan Wei Zhongxin 宋代丹道南宗發展史研究—以張伯端與白玉蟾為中心 [The Evolution of Inner Alchemy of Southern Lineage in Song Dynasty—Centering Around Zhang Boduan and Bai Yuchan]. Doctoral Dissertation, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Jinlan 曾金蘭. 2009. Wu Fu San Jue Yu Bai Yuchan 烏符三絕與白玉蟾 [Three Wonders of Wufu and Bai Yuchan]. Hunan Keji Xueyuan Xuebao 湖南科技學院學報 10: 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Guangbao. 2001. Tang Song Neidan Daojiao唐宋內丹道教 [Inner Alchemy Daoism in the Tang and Song Dynasties]. Shanghai: Shanghai Wenhua Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Weiwen. 2019. Lineage Construction of the Southern School from Zhongli Quan to Liu Haichan and Zhang Boduan. Religions 10: 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Xibian 趙希弁. 2011. Dushu Fuzhi 讀書附志 [Reading Notes Supplement]. In Junzhai Dushuzhi Jiaozheng 郡齋讀書志校證 [Collated Notes on Junzhai’s Bibliographic Records]. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, Dexiu 真德秀. 1989. Xishan Zhen Wenzhonggong Wenji 西山真文忠公文集 [Collected Works of Zhen Dexiu]. In Sibu Congkan Chubian Jibu 四部叢刊初編集部[First Series of the Four Treasuries Collection, Literary Division]. Shanghai: Shanghaishudian, vol. 210. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, C.; Jiang, Z. Itinerancy and Sojourn: Bai Yuchan’s Travels as the Early Dissemination History of Daoism’s Southern School. Religions 2025, 16, 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080950

Dong C, Jiang Z. Itinerancy and Sojourn: Bai Yuchan’s Travels as the Early Dissemination History of Daoism’s Southern School. Religions. 2025; 16(8):950. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080950

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Cunbin, and Zhenhua Jiang. 2025. "Itinerancy and Sojourn: Bai Yuchan’s Travels as the Early Dissemination History of Daoism’s Southern School" Religions 16, no. 8: 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080950

APA StyleDong, C., & Jiang, Z. (2025). Itinerancy and Sojourn: Bai Yuchan’s Travels as the Early Dissemination History of Daoism’s Southern School. Religions, 16(8), 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080950