Māori Before English: Religious Education in Aotearoa NZ Ko tōku reo tōku ohooho, ko tōku reo tōku māpihi maurea—My Language Is My Awakening, My Language Is the Window to My Soul

Abstract

1. Part 1: Tō Tātou Whakapono Our Faith

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Context

1.2.1. Beginnings

1.2.2. Catholic Education

1.3. Curriculum Overview

1.3.1. The Name: Tō Tātou Whakapono Our Faith

1.3.2. Purpose of Religious Education

1.3.3. Method or Pedagogy Employed

- God, the Church, and the environment are in a relationship. ‘It is as community that we engage in the learning process, and this principle underlies all pedagogical decisions’ (NCRS 2024, p. 16).

- Both teacher and learner invest in the learning process, each with their own responsibilities. For teachers, it begins with knowing their learners who have agency in the acquisition and interpretation of knowledge.

- There is a transformative dimension to RE as a cycle of reflection, action, and reflection as children integrate ‘a Catholic worldview into their understandings’ (NCRS 2024, p. 16).

- ‘In a complex world and in challenging times, it is important to encourage anticipation, joy and hope through learning experiences’ (NCRS 2024, p. 16).

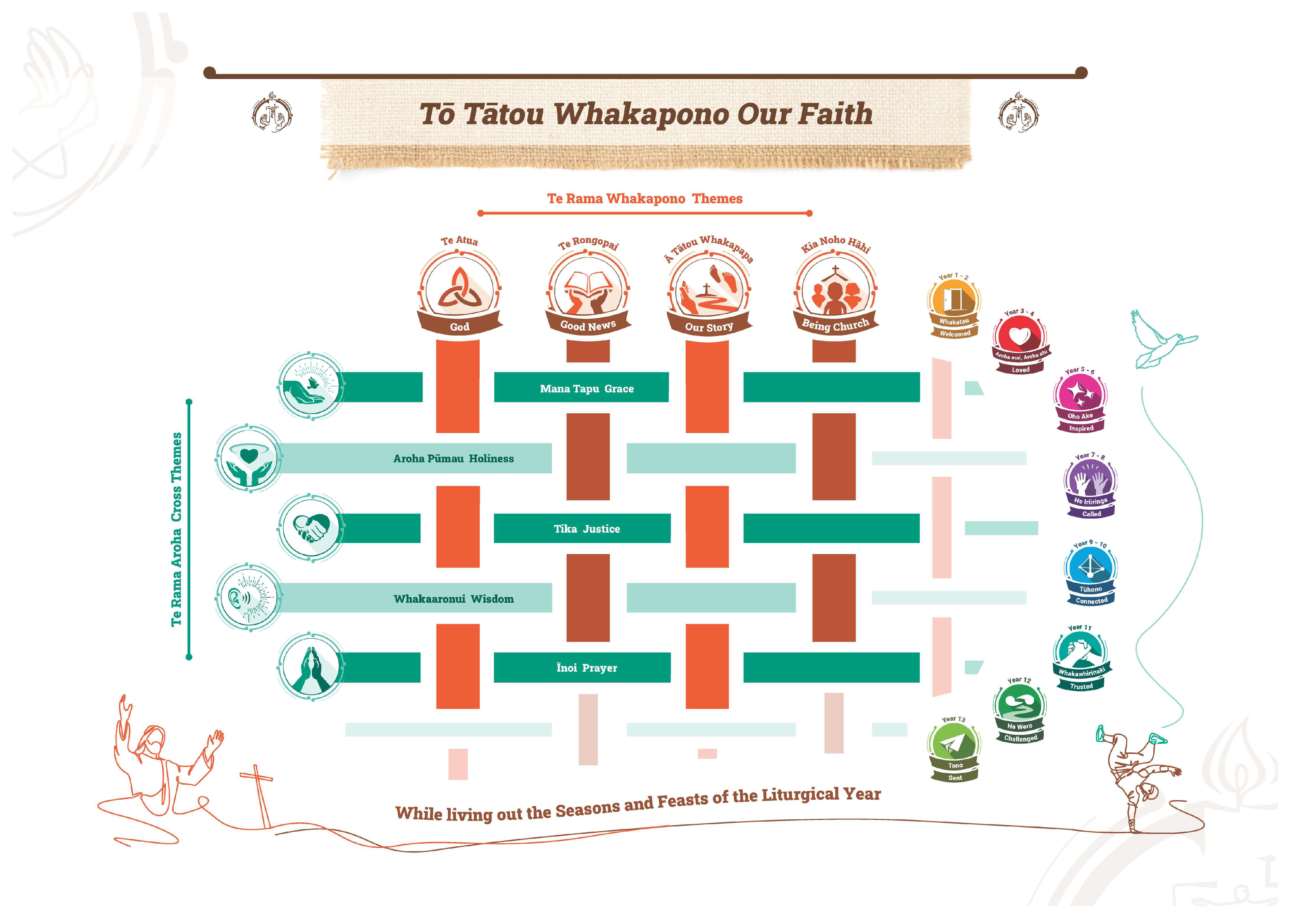

1.3.4. Structural Elements

Te Rama Whakapono Light of Faith Themes

Te Rama Aroha Light of Love Themes

Ngā Kaupapa Content Areas and Ngā Whāinga Paetae Achievement Objectives

Ngā Kōhatu Touchstone

At a Glance

1.3.5. The Curriculum at Work: Te Atua God

The Whānau Family Page

The Learning Packs

- Background Notes.

- Suggestions for Teachers.

- Learning Resources.

- Overview Documents.

1.4. Discussion

2. Part 2: A New Hermeneutical Lens

2.1. Introduction

2.2. Beginning with God

2.3. Metaphors for God in the Bible

2.4. How Metaphors Work

3. Theology from Within

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowie, Robert A., and Richard Coles. 2018. We reap what we sew: Perpetuating biblical illiteracy in new English Religious Studies exams and the proof text binary question. British Journal of Religious Education 40: 277–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carswell, Margaret. 2006. Biblical Metaphors for God in the Primary Level of the Religious Education Series To Know Worship and Love. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Carswell, Margaret. 2018a. Promoting fundamentalist belief? How scripture is presented in three religious education programmes in Catholic primary schools in Australia and England and Wales. British Journal of Religious Education 40: 288–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carswell, Margaret. 2018b. Teaching Scripture: Moving towards a hermeneutical model for religious education in Australian Catholic Schools. Journal of Religious Education 66: 213–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carswell, Margaret, Gretchen Geng, Stephanie Carswell, and Matthew Zbaracki. 2025. ‘The limits of my language means the limits of my world’: An examination of the Post Critical Belief Scale survey instrument, for pupils with English as an additional language. Journal of Religious Education 73: 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1997, Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/_INDEX.HTM (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Catholic Diocese of Auckland. n.d. Catholic Schools. Available online: https://www.aucklandcatholic.org.nz/catholic-schools-2/ (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Erdozain, Luis. 1983. The evolution of catechetics: A survey of six international study weeks on catechetics. In Book for Modern Catechetics. Edited by Michael Warren. Winona: Christian Brothers Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, John C. 1998. Language and Imagery in the Old Testament. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, Michael James. 2003. The Use of Scripture in the Teaching of Religious Education in Victorian Catholic Secondary Schools. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Holm, Jean. 1983. Teaching Religion in School. A Practical Approach. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hymes, Dell H. 2024. On communicative competence. In Sociolinguistics: Selected Readings. Edited by J. B. Pride and Janet Holmes. Harmondsworth: Penguin, pp. 269–93. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Oliver A. 1965. God and St Anselm. The Journal of Religion 45: 326–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macky, Peter. 1990. The Centrality of Metaphors to Biblical Thought. A method for interpreting the Bible. In Studies in the Bible and Early Christianity. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, vol. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Madgen, Deborah. 1993. The Use of the Bible in Australian Catholic Primary School: A Critical Examination of Approaches to Teaching the Bible in Curriculum Documents Used in Australian Catholic Primary Schools. Unpublished Master’s thesis, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Mary E. 1998. Images of God in the Old Testament. London: Cassell. [Google Scholar]

- National Centre for Religious Studies. 2024. Tō Tātou Whakapono Our Faith. Available online: https://www.totatouwhakapono.nz/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- New Zealand Catholic Bishops Conference. n.d.a. Bishop Lowe Celebrates 185th Anniversary of First NZ Catholic Mass at Totara Point. Available online: https://www.catholic.org.nz/news/media-releases/totara-185/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- New Zealand Catholic Bishops Conference. n.d.b. History. Available online: https://www.catholic.org.nz/about-us/history/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- New Zealand Catholic Education Office. 2020. New Zealand Legislation Special Character Obligations Required of Boards of Trustees of Catholic Integrated Schools. Available online: https://www.nzceo.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Spec-Character-Legal-obligations-.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- New Zealand Catholic Education Office. 2025. Integration. Available online: https://www.nzceohandbook.org.nz/integration/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- New Zealand Catholic Education Office. n.d. History of Integration. You Tube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=48sBEftCDr4&t=36s (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- New Zealand Government. n.d. Land Confiscation Law Passed. Available online: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/the-new-zealand-settlements-act-passed (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- New Zealand Government Parliamentary Office. n.d. Private Schools Conditional Integration Act 1975. Available online: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1975/0129/latest/whole.html#:~:text=This%20Act%20may%20be%20cited,different%20provisions%20of%20this%20Act (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Pollefeyt, Didier, and Reimund Bieringer. 2005. The role of the Bible in Religious Education Reconsidered. Risks and challenges in teaching the Bible. International Journal of Practical Theology 9: 117–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, Kate. 2020. The Bilingual Brilliance of Sir Tīmoti Kāretu. Available online: https://thebigidea.nz/stories/the-bilingual-brilliance-of-sir-timoti-karetu (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Schneiders, Sandra M. 1986. Women and the Word. Mahwah: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stead, Barbara. 1996. The Influence of Critical Biblical Study on the Teaching and Use of Scripture in Catholic Schools in Victoria. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, La Trobe University, Victoria, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, H. 2010. Towards Some Foundations of a Systematic Māori Theology. He tirohanga anganui ki ētahi kaupapa hōhonu mō te whakapono Māori. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Melbourne College of Divinity, Box Hill, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal. 2025. Waikato Tribes, Te Ara—The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Available online: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/waikato-tribes/print (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Van Wijk-Bos, Johanna. 1995. Reimagining God. The Case for Scriptural Diversity. Louisville: John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1961. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Translated by David F. Pears, and Brian F. McGuinnes. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carswell, M.; MacLeod, C.; Lanner, L. Māori Before English: Religious Education in Aotearoa NZ Ko tōku reo tōku ohooho, ko tōku reo tōku māpihi maurea—My Language Is My Awakening, My Language Is the Window to My Soul. Religions 2025, 16, 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080947

Carswell M, MacLeod C, Lanner L. Māori Before English: Religious Education in Aotearoa NZ Ko tōku reo tōku ohooho, ko tōku reo tōku māpihi maurea—My Language Is My Awakening, My Language Is the Window to My Soul. Religions. 2025; 16(8):947. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080947

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarswell, Margaret, Colin MacLeod, and Laurel Lanner. 2025. "Māori Before English: Religious Education in Aotearoa NZ Ko tōku reo tōku ohooho, ko tōku reo tōku māpihi maurea—My Language Is My Awakening, My Language Is the Window to My Soul" Religions 16, no. 8: 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080947

APA StyleCarswell, M., MacLeod, C., & Lanner, L. (2025). Māori Before English: Religious Education in Aotearoa NZ Ko tōku reo tōku ohooho, ko tōku reo tōku māpihi maurea—My Language Is My Awakening, My Language Is the Window to My Soul. Religions, 16(8), 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16080947