Abstract

This article examines how student voice informed the development of Tō Tātou Whakapono Our Faith, the national Religious Education (RE) curriculum for Catholic schools in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Through student-submitted RE questions and 63 informal Zoom-based “Interschool Catholic Yarns” with over 400 senior students over several years, the National Centre for Religious Studies gathered valuable insights into student experience and expectations. These contributions influenced RE curriculum content, nuance, and priorities. Emphasising accessible engagement with young people, the two outlined approaches align with Catholic commitments to synodality and formation. This article demonstrates that engaging student voice is both possible and necessary in designing RE that is meaningful, faithful, and grounded.

1. Introduction

The title of this article is a quote from a 17–18 year old young woman in a Catholic high school. She suggests that too many adults have ‘stayed’ Catholic without actually practicing what it means to ‘be’ Catholic. It is one example of insights and challenges gained from senior students in Catholic high schools in Aotearoa NZ1, via two accessible approaches to gathering student voice. The director of the National Centre for Religious Studies (NCRS), the Catholic agency providing Religious Education curricula and materials for all Catholic schools in this country, has conducted ongoing Zoom conversations with senior secondary students in Catholic schools seeking such wisdom. These sessions are intentionally not methodical research but are rather, as billed with the students and organising staff, an “Interschool Catholic Yarn” (ICY)—a Zoom conversation between himself and students to seek informal feedback and advice about RE from their perspectives. The resulting student contributions, along with students’ RE questions, have informed design and resources for the new RE curriculum for Aotearoa NZ: Tō Tātou Whakapono Our Faith (TTWOF) ().

2. Context

Aotearoa NZ has 49 Catholic Secondary schools2 and 185 Catholic Primary schools across all six dioceses, educating around 67,000 young people who represent eight percent of the total student population (). These statistics have remained relatively stable over the past 10 years, despite a national climate of rising secularisation and declining religious involvement, aligned with most of the Western world (; ). Until 2021, all primary schools taught the Primary Religious Education (RE) curriculum () and all but one3 secondary school delivered the senior RE curriculum Understanding Faith (), as mandated by the NZ Catholic Bishops’ Conference and as designed and resourced through their agency the National Centre for Religious Studies. In mid 2016, when the current director of NCRS was appointed, both curricula were over 20 years old, apart from minor revisions, and there was a general outcry from principals and RE leaders and teachers not just for an update to the old material and context but for a completely new RE curriculum.

A unique factor of Aotearoa NZ is that all Catholic schools have an individual integration agreement with the NZ Government whereby they are required to maintain a Catholic ‘special character’, which includes the teaching of Religious Education. Linked with this, Catholic schools also have an enrolment system called ‘preference’ whereby a high percentage of the maximum roll, usually 95%, must include “those children whose parents have established a particular or general religious connection with the special character of the school” (). There is a national process for each diocese, managing the granting of such preference (). This situation is set in law, with all Catholic schools being ‘state-integrated’ schools, meaning they are not private or independent but have a legislative agreement between the Government4 and the proprietor of each school, usually the diocesan bishop, where schools are funded by the Ministry of Education for their day-to-day operation (including staff salaries and the maintenance of the school buildings and grounds). As a result, in theory, 95% of students in Catholic schools and their families are committed to the faith dimension of the school. The reality is much more complex in practice, with the technical criteria for preference, such as the child having received the Catholic sacrament of Baptism, often masking little or no current familial or personal faith practice such as regular Mass attendance (; ).

This particular education context is significant for Catholic RE curriculum development in Aotearoa NZ, because unlike many countries the challenge to address pluralism within Catholic schools, such as outlined by () and (), is mitigated by a legal protection that RE is expected to be Catholic. There is sensitivity towards the five or so percent of students who may hold other faiths or none, and there is awareness that many, perhaps most, Catholic students are disconnected from beliefs and practices of the Church. Aotearoa NZ Catholic schools are not without students who are unhappy with Catholic RE and having to conform to Catholic practices, as evidenced internationally (; ). However, families enrol young people in a Catholic school in this country knowing Religious Education will be Catholic, as affirmed by them in their preference enrolment process and as supported in the secular law of the land regarding Catholic state-integrated schools. This is further considered reasonable in the Aotearoa NZ educational landscape because it is usual for other, non-religious, schools to be available as an alternative for enrolment.

It is within this rather simplified context that the journey towards a new national RE curriculum began in 2018. Myriad international RE curricula were read and analysed by the NCRS team, with components carefully noted and discussed in the drafting process. Many groups and individuals were consulted, working parties gathered, and multiple drafts formed and revised before Tō Tātou Whakapono Our Faith was released by the NZ Catholic Bishops’ Conference in December 2021. However, those elements are not the focus here.

This article describes both the approaches and outcomes of intentionally seeking and including one critical element of curriculum development often omitted in the literature–that of student voice.

3. Approaches for Gathering and Including Student Voice

3.1. Student RE Questions

Given the long-term call for a new RE curriculum, in early 2018, NCRS committed to quickly producing two bridging documents, one each for primary schools () and secondary schools (), to draw together concepts in current curricula and to begin a process of determining new directions for an unknown future curriculum. A critical point for considering such new directions was to ask young people what RE questions they had.

An invitational poster was made with a prompting word-map of as many RE words as the author could muster at the time, such as: Saints, Mass, Jesus, God, Heaven, Relationships, Gospel, etc., and a heading saying, “Send us your RE Questions!!” A QR code linking to a URL for a Google form, which was also present as an easily typed ‘tinyurl’, was included, along with the NCRS logo (See Figure 1). A short e-mail was sent to all Aotearoa NZ Catholic schools asking teachers to put the poster in prominent places and encourage students to send in their questions.

Figure 1.

A screenshot of the A4 poster sent to all Catholic schools.

The form itself presented four fields, only the first two of which were compulsory: ‘What year are you in?’, ‘What is a question you would really like to have answered in RE?’, ‘You can ask another question if you want’, and, ‘Any extra comment?’ Encouraging descriptors were added below each prompt.

The response was exceedingly useful in terms of encouraging direction for the NCRS team, but also disappointing in that only 640 questions were received. The number of responses were fairly evenly spread across all levels. An unexpected personal challenge, since the survey was rightly completely anonymous, was the lack of opportunity to reply directly to these very real young people who posed such engaging questions and who clearly sought answers.

Despite a relatively low response, the questions received were a powerful insight into what an RE curriculum needs to answer for our young people. The following are a few samples:

Five- and six-year-old children asked: Why did Jesus carry a cross? Why did Jesus pray to God? Where is the Pope’s house? Does God have a penis? How can God be inside our heart?

Seven and eight year olds asked: How did Mary get pregnant? Did God create the Big Bang Theory? Is God a person or a light? Why does God love everyone including the bad people? How does the Holy Spirit work in my heart? How far did Jesus walk in his life?

Nine and ten year olds asked: What does God look like? What religion was Jesus? What is the purpose of RE? Who was the person that made the Bible? Why did God make the Trinity? Why are there different types of Churches? How does God watch us all at the same time? How do we know if the Bible is real? Was all the water fresh? Did God use magic?

Eleven and twelve year olds asked: Why does God let people die painfully, babies with cancer, people with diseases? God flooded the world because he wasn’t pleased with humans, so will he flood us for causing global warming? If Mary was a virgin how did she have other kids? How did churches start? Did God create himself? Is Jesus really God’s son?

Thirteen and fourteen year olds asked: If God knew that his son was going to die, why did he let it happen? Do you really believe Jesus did all those miracles? Did Adam and Eve, and descendants, procreate by incest? Why do people get visions of angels? Why doesn’t God help Satan become a better person? Why is the Catholic Church against gay people–they’re normal people and it doesn’t matter who they love or marry?

Fifteen and sixteen year olds asked: Jesus was born or not, I can’t believe the story about Jesus? Why did the pope remove the concept of Limbo? Why is Jesus the main focus of the Church instead of God? How do the morals and ethics of religious people compare to the ones of non-religious people? Why does a religion have to be forced upon us when some people may not believe the same as everyone else?

Seventeen and eighteen year olds asked: How will the Church cope in a rapidly progressing world that is becoming much more liberal? Why does God allow suffering? In which ways is Christianity a good alternative to other religions? Why did Jesus go to Hell and then go to Heaven? Why do you hate gays?

All questions were collated into a nine-page document ordered under year levels, and colour coded into groups indicated by the themes perceived within the questions themselves: God-Creator, Jesus, Holy Spirit, Afterlife, Church, Liturgy/Liturgical Year; Saints, Scripture, History, Justice, Prayer, and General. These pages were printed and affixed to the NCRS office wall. As the bridging documents and subsequent new curriculum took shape, they were regularly perused in an authentic effort to account for each question being addressed somewhere within the RE curriculum.

It is important to note that the intent was never to apply a technical, clinical, research tool or method to this data. The goal was to gather questions from our young people so that the NCRS team, especially the author who oversaw the projects, could gain and retain specific voice of the young people being served–to check in with “what do the students in the classrooms today want and expect?” (). Multiple questions became core elements of ongoing discussion, and many were shared back with principals and teachers during curriculum-drafting consultation as examples of what young people were seeking and of what NCRS was attempting to construct and provide. These questions grounded the team in some of the reality of students and fostered a warm sense of connection to their lives. The questions supported a commitment not only to the technical elements of an emerging curriculum, but a palpable connection to actual hearts and minds in Catholic school classrooms.

3.2. Interschool Catholic Yarns

In addition, within six months of taking on the leadership role in NCRS, the author sought an ongoing process which would provide regular contextual information from young people, with minimal additional workload pressures for himself or the organising teachers and participating students in schools. Conversations with other experienced researchers within the wider Catholic Institute5 at the time supported an open, anonymous, and inclusive approach where all parties were made aware of ethical and participatory elements within the process, especially the protection of anonymity and option to withdraw at any time.

A prior casual conversation with an enthusiastic past student on the streets of Dunedin proffered the title “Interschool Catholic Yarn” (ICY). The ex-student readily grasped the intent to gather honest and grounded information from students about current and potential RE content and context in Catholic school classrooms. He simply stated, “You just want to have an interschool Catholic yarn with them.” Thus, the name was established, and the informality of the process was affirmed.

The next step in planning was to determine who and how to have that yarn. Previous personal teaching experience, along with conversations with other teachers, indicated Year 126 students would be ideal: Most would have experienced RE in the junior years and they would also have completed one year of formal examination of RE under Religious Studies in the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (). They would bring a certain maturity, and some contextual benefit in being students who were still invested in future RE rather than final-year, Year 13, students who may be more cognisant of RE discontinuing for them at the end of the year.

Zoom, which was relatively new and innovative in 2016, especially before COVID-19 influenced the widespread embracing of such technologies, added both an effective means of connecting and a technological appeal to students at the time. The potential of the technology itself encouraged the decision to give students the opportunity to engage in a conversation with the author alongside another group of students from a different school. Also, by conversing with two groups of students at the same time, there was the opportunity to springboard off each other’s comments and engage in short bursts of inter-school dialogue to tease out an idea or experience. An important additional benefit of conversing with two schools at a time was to mitigate the ethical dilemma of ensuring participant comments were not only anonymous in terms of individual contributions but also in terms of identifying their originating school.

Springboard questions were set and have been used for all ICYs with only minor development, though, in practice, the conversation would often range beyond these opening queries. The intent was for the first two questions to support students being at ease by talking about their own school and positive RE experiences, then gradually, arguably, moving into deeper personal territory:

What’s great about your school?

What are the best three things about RE?

What is something you might like to change in RE?

What do you like in RE resources? (activities, types of images, texts, etc)

How else do you think the Catholic ‘thing’ adds to your school?

What do your non-Catholic friends think about RE?

How does RE support your personal relationship with Jesus (personal spirituality)?

Finally, is there anything you’d like to ask me or tell me. (Or ask each other?)

The time-frame was set to 30 min for each ICY. However, this often extended up to 45 min with permission of the participating young people, as per an agreed possibility with organising teachers prior to the session. ICYs were not permitted to go longer than 45 min, lest the potential wrath of other subject teachers missing their students establish a negative attitude towards the process and hinder such opportunities in subsequent years.

If, last minute, a school group did not turn up to the assigned ICY, the conversation could be held with a single school, or they would be given the option of having another time assigned. No groups took up this latter option. The missing group would be given the opportunity to connect in another ICY, paired with a different school if possible, or as an individual group if no additional schools were available.

It was decided that students would feel more free to contribute if ICYs were not digitally recorded, but notes would be taken throughout the conversation with the intention of capturing key phrases as close to verbatim as possible. Notes do not include specific references to students or schools. At the same time, with the students knowing what had been said during an ICY, typed notes would later, usually the same day, be e-mailed to them giving an opportunity to clarify or change points they may have made.7 Students were informed at the start of each ICY that the anonymised notes would be shared with them, and with the organising teacher/s at their school, as well as being used by NCRS. An invitation to withdraw from the ICY if they wished was included in the introduction, though none chose to do so. (N.B. With single-school ICYs, students gave verbal permission that their school, but not them personally, would be recognisable in the local sharing of notes).

With these processes in place, in 2016, all NZ Catholic secondary schools were invited by e-mail, with explanatory information, to participate in an Interschool Catholic Yarn. Those schools who chose to reply were accepted, and schools were set up in pairs, and e-mailed a date, time, and meeting link. ICY volunteer participants were small groups of 16–18 year olds, either self-selected, or selected by their teacher. Often teachers, wisely, handed over the full organisation to the students themselves. Comments within group conversations indicate that participating students range from self-proclaimed atheists to committed practicing Catholics. Conversations were held, and anonymous comments have been noted, shared and utilised by NCRS. This approach has been replicated many times.

At time of writing, seven rounds of ICYs have taken place—annually from 2016 to 2019, then in 2021, 2023, and 2025. There have been 63 Interschool Catholic Yarns in total, involving 117 groups of students from Catholic secondary schools. (Including ICYs with a single school due to the other forgetting to turn up or other extenuating circumstances.) Group sizes have ranged from 2 to 14 students per school at a time. In total, 428 students have taken part, with just under two thirds being girls. In terms of school representation, out of 48 Catholic schools teaching year 12, 11 out of 17 boys’ schools have participated, along with 11 of 14 girls’ schools and 16 of 17 co-ed schools. Regarding recurring decisions to engage with an ICY, 10 schools have never participated, 5 have participated once, 14 twice, 12 three times, 2 four times, 4 five times, and none have participated in more than five. All of which has resulted in over 26 thousand words of student comments.

While the following examples reinforce the worth of such an approach in curriculum design, it is important to also note that at the end of ICYs, students have consistently indicated their gratitude at having their voice sought, and of having been listened to. Teachers e-mailing back, after the typed-up notes have been received, also comment on how much the students enjoyed the experience, and thank NCRS for the opportunity of letting their students speak and be heard. From the beginning steps it was recognised that there was benefit in this experience. There is a sense of overt synergy with the ICY process and the current synodal Catholic call to listen to one another (). Our young people wish to be heard.

At the same time, as curriculum designers, the gift of what they actually say is invaluable! There is little doubt that the “Church can better respond to contemporary challenges and fulfil its mission of evangelization if all members are participating in dialogue” (). This is particularly so with regard to developing quality meaningful Religious Education.

4. Examples and Utilisation of ICY Student Voice

It is important, again, to recognise that the impetus behind these conversations has always been to ‘check-in’ and keep ‘grounded’ with our young people rather than to engage with in-depth analysis. As with the collection of students’ questions, the goal of ICYs is to hear the voice of the young people whom RE is intended to serve. Comments have significant synergy with Australian findings (), and with international approaches to RE content and direction (; ). However, perhaps more importantly for NCRS, they inform the nuance of the new RE curriculum for Aotearoa NZ. It is in this context of trying to learn not just where our young people are at, and what they are needing, but what they are observing and offering as insights, that the power of Interschool Catholic Yarns comes to the fore. For the author, it is not so much the collective themes or commonality of understandings that give the greatest value, so much as the specificity of single comments that can leap out of the familiar themes to capture a nuance which introduces a whole new perspective for curriculum writing.

Myriad comments, such as capacity of teachers, desire for interactive discussion, and inclusion of learning about other faiths, align with the student voice research of () and have merit as such. However, a focus for the author was capturing phrases and nuances which could be used both as a point of reflection and direction for developers of curriculum, and also as a reinforcement for particular approaches when shared with bishops, school principals, and RE leaders and teachers.

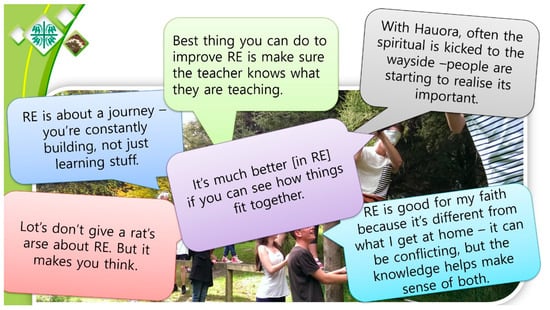

The PowerPoint slide captured in Figure 2 was used in dozens of workshops around Aotearoa NZ in 2021 as TTWOF was coming together as a curriculum. (The background photograph was of a group of Year 12 students on a trust walk during a Catholic school retreat.) It presents quotes from ICY conversations as a solid set of examples, which as the following discussion explains, reflect the impact of student voice in the curriculum development. It also served to help connect Catholic school principals and other RE leaders to the intent, purpose, and challenge of RE.

Figure 2.

A screenshot of a PowerPoint slide used in consultation with principals and other RE leaders.

“With hauora8, often the spiritual is kicked to the wayside–people are starting to realise its important” (18 June 2021).

“RE is about a journey–you’re constantly building, not just learning stuff” (14 September 2016).

The NCRS team had been reflecting on background ideas of spirituality, pilgrimage, and journey as young people moved through RE in Catholic schools. Hauora is a Māori concept of health and wellbeing, encompassing physical, mental, social, and spiritual needs. These comments re-emphasised the concept of young people being on a spiritual journey as central not just peripheral to their RE learning: The term ‘hīkoi wairua spiritual journey’ is therefore present throughout TTWOF, as a key concept, with one particular section explaining the concept in depth ().

“Best thing you can do to improve RE is make sure the teacher knows what they are teaching” (25 June 2021).

There had been some initial thinking that theological knowledge would be provided separately from curriculum resources. In conjunction with deeper conversations with teachers, NCRS grasped this ICY comment, and as an important step in the challenge of equipping teachers to provide quality RE, committed to creating detailed ‘Background Notes’ to accompany all resources created for schools.9

“Lots don’t give a rat’s arse about RE. But it makes you think” (16 June 2021).

The explicit truth of this comment, in the author’s experience, is difficult to ignore, and is ignored at an RE curriculum development team’s peril. The reality is that many may not engage in the spiritual and faith dimensions of RE learning. However, hope lies in resources which engage students and at least make them think. Tō Tātou Whakapono Our Faith states, “Participation in RE does not require or even expect a personal faith commitment from learners, however, it is expected that young people will engage with the knowledge and learning experiences: to enter into the dialogue” (). The challenge is accepted by the NCRS team in remembering those who do not care about RE by creating engaging resources with them in mind. NCRS’s part in ‘entering into the dialogue’ is also represented in seeking and listening to the ICY comment itself (and others like it).

“It’s much better [in RE] if you can see how things fit together” (11 June 2019).

While not a novel pedagogical concept, the clarity of this phrase supported a commitment to coherence and cohesion within design and resources. These two terms have become foundational for the director of NCRS, originating in ’s () new pedagogies for deeper learning, but contextualised in this ICY comment. The integrated curriculum design () and approach to resource development supports overt weaving of concepts so teachers and students may see how RE learning ‘fits together’.

“RE is good for my faith because it’s different from what I get at home–it can be conflicting, but the knowledge helps make sense of both” (28 June 2021).

With increasing immigration and changing cultural demographics in Aotearoa NZ impacting the religious landscape of this country (, ), there was a sense in the NCRS team that young people from ‘faith-filled’ families would already know much of the content being planned for a broad spectrum of faith engagement or a lack thereof. This ICY statement recalibrated NCRS to an awareness that the complexity was deeper than faith connections. The implied reality is that many faithful parents of children in Catholic schools do not have a depth of RE knowledge. Young people are seeking more knowledge. The reciprocal awareness is that some knowledge can be challenging for parents, and children need to be supported in recognising faith and knowledge as supportive on their faith hīkoi wairua, along with the faith journey of their wider family. NCRS is careful to be sensitive of this reality in our resources.

Finally, two more recent examples are provided to reflect the ongoing support that ICY conversations have for NCRS’s ongoing RE curriculum work:

“It’s [RE] helped me. I grew up in a Catholic family and RE has helped me so much. Without RE I only have family opinions and Mass to go off. It’s opened my eyes. They’re not teaching us in parishes or in families” (28 June 2023).

There is a wealth of planning and resources for RE in Catholic schools, and a commitment to ongoing development in this area. With so much content already available, this comment prompts NCRS to reach out to diocesan offices and investigate ways in which materials might be shared outside of schools, in parishes, and even developed for adults. The director of NCRS is just beginning to have conversations with diocesan representatives in this regard.

“You can’t slap [Catholic] identity on to someone without informing them. Understanding leads to faith choices” (20 May 2025).

This surprising statement aligns closely with current research into the relationship between parishes and parish schools in Aotearoa NZ, in which identity is named as a central element (). The observation that RE plays a role in forming Catholic identity, rather than it being ‘slapped’ onto individuals from presupposed faith assumptions, is a critical area of reflection not just for future Catholic education but for future identities of the Church itself.

5. Conclusions

There is a phrase often used by those living with disabilities, and by many commonly marginalised groups, when engaging with governmental or other support agencies: Nothing about us, without us. For similar reasons of inclusion, respect, and potential effectiveness, the same resonates with young people in Aotearoa NZ Catholic secondary school RE. This article outlines two straightforward approaches which have served, and continue to serve, NCRS in the development of a new RE curriculum and ongoing associated resources.

If it were not for student voice, the director of NCRS could easily be leading RE curriculum projects with the sole focus of providing secular-quality RE direction and resources as expected by the bishops and other Catholic education managers. Instead, he finds himself also checking whether the materials are helping young people and their teachers to ‘be Catholic’ or just ‘stay Catholic’. That is the power of student voice.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The approaches described in the article were conducted with clear ethical intent, appropriate oversight, and respect for the dignity and autonomy of all participants. While not framed as formal research requiring IRB approval, every effort was made to ensure that ethical standards—consistent with best practice in educational consultation—were upheld. I trust this contextualisation clarifies the rationale for not seeking formal ethics review at the time and affirms the integrity with which these authentic approaches, to receive the ‘voice’ of the students themselves, were conducted.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this study are not stored in a publicly accessible repository but are available on request from correspondence author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Aotearoa NZ is a common term for New Zealand as it is inclusive of indigenous Māori. |

| 2 | Note, St Ignatius of Loyola College opened in Auckland in 2024 and does not have senior students yet. |

| 3 | St Peter’s College, Auckland, was granted interim exemption by +Patrick Dunn in 2007. |

| 4 | Private Schools Conditional Integration Act (1977), continued in the Education and Training Act (2020). |

| 5 | The Catholic Institute (TCI) was the parent agency of NCRS when ICYs began, this later became Te Kupenga—Catholic Leadership Institute in 2020. |

| 6 | Year 12 (16–17 year olds) in Aotearoa NZ secondary schools is the penultimate year of secondary education, with year 13 being the final year. |

| 7 | Over 63 ICYs very few corrections have been received from students, but in 2019 one group wrote an addendum of three paragraphs to extend a concept, and after a separate ICY one student wrote a 526 word follow-up e-mail with additional contributions. |

| 8 | A te reo Māori term, commonly used in Aotearoa NZ education, meaning health and well-being. |

| 9 | Resources are provided for teachers with permissions on the NCRS TTWOF website: www.ourfaith.nz. |

References

- Buchanan, Michael T., and Adrian-Mario Gellel. 2019. Global Perspectives on Catholic Religious Education in Schools. Learning and Leading in a Pluralist World. Singapore: Springer, vol. 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faller, Paul. 2019. The student voice in South African Catholic school religious education. In Global Perspectives on Catholic Religious Education in Schools: Learning and Leading in a Pluralist World. Edited by Michael T. Buchanan and Adrian-Mario Gellel. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis. 2021. Address of His Holiness Pope Francis for the Opening of the Synod. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2021/september/documents/20210918-fedeli-diocesiroma.html (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Fullan, Michael. 2015. Leadership from the middle: A system strategy. Education Canada 55: 22. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson, Jim, and Peta Goldburg. 2020. Faith-Based Identity and Curriculum in Catholic Schools, 1st ed. Abingdon: Routledge. Oxon: Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon, David Gerard. 2010. What Constitutes Success in Classroom Religious Education? A Study of Secondary Religious Teachers’ Understandings of the Nature and Purposes of Religious Education in Catholic Schools 2vols. Ph.D. thesis, Australian Catholic University, Fitzroy, VIC, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Larkins, Geraldine, and Siân Owen. 2025. Why there Is a place for dialogue in religious education today. Religions 16: 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, Colin. 2025. They Too Belong Here: Investigating the Relationship Between Catholic Parishes and Parish Schools in Aotearoa New Zealand. Ph.D. thesis, Faculty of Education, Australian Catholic University, Sydney, Australia. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, Graeme. 2024. Something is not working! Reimagining religious education in today’s Catholic school: The All Black culture, the Samaritan woman at the well, the ANZAC mythology and the crucial importance of formative contexts. Religions 15: 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Centre for Religious Studies. 1997. Religious Education Curriculum Statement for Catholic Primary Schools in Aotearoa New Zealand. Available online: www.faithalive.org.nz (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- NCRS. 2010. Understanding Faith: Religious Education Curriculum Statement for Catholic Secondary Schools, Years 9–13, Aotearoa New Zealand. Available online: www.faithcentral.co.nz (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- NCRS. 2018a. The Religious Education Bridging Document. Available online: http://www.faithalive.org.nz/assets/REBD/The-REBD-2018-V2.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- NCRS. 2018b. The Secondary Religious Education Bridging Document. Available online: https://www.faithcentral.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/The-Secondary-REBD-Final.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- NCRS. 2021. Tō Tātou Whakapono Our Faith: Religious Education Curriculum for Catholic Schools in Aotearoa New Zealand. Available online: https://tekupengactc.sharepoint.com/:b:/s/External/EXcyfwQz_s5OtYEzPUc91QoBo6hXmMareMCiIqVDBUDVeg?e=J5XqXL (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- New Zealand Catholic Education Office. 2020a. Guidelines for the Granting of Preference of Enrolment in New Zealand Catholic schools–Updated by the NZ Catholic Bishops Conference, November 2018. Available online: https://tekupengactc.sharepoint.com/:b:/s/External/EZddt_p3_cJLsEprL_0QgYEByhYz2w1GjNJ1O0-FkGERXg?e=LDWBUu (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- New Zealand Catholic Education Office. 2020b. Handbook for Boards of Trustees of New Zealand Catholic State-Integrated Schools. Available online: https://www.nzceohandbook.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Handbook-A4.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- New Zealand Catholic Education Office. 2024. Annual Report 2023. Available online: https://www.nzceo.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/NZCEO-2024-Annual-Report-09-screen.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- New Zealand Qualifications Authority. 2025. Available online: https://www2.nzqa.govt.nz/ncea/about-ncea/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Owen, Siân Maree. 2018. How the Principals of New Zealand Catholic Secondary Schools Understand and Implement Special Character. Ph.D. thesis, Australian Catholic University, Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, Catherine. 2020. The voice of minority faith and worldview students in post-primary schools with a Catholic ethos in Ireland. Irish Educational Studies 39: 457–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanden, Kevin, and Lyn Birch. 2007. Catholic schools in New Zealand. In International Handbook of Catholic Education: Challenges for School Systems in the 21st Century. Edited by Gerald Grace and Joseph O’keefe. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 847–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wilberforce Foundation. 2018. Faith and Belief in New Zealand. McCrindle. Available online: https://nzfaithandbeliefstudy.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/faith-and-belief-full-report-may-2018.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Wilberforce Foundation. 2023. Faith and Belief: Te Patapātai Whakapono–Exploring the Spiritual Landscape of Aotearoa New Zealand. Available online: https://nzfaithandbeliefstudy.files.wordpress.com/2023/11/willberforce-report-2023-digital-2.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).