1. Introduction

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) is reshaping fields such as education, ethics, and theology (

Guo et al. 2021;

Ignatowski et al. 2024;

Kawka 2025). The current revolution in Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transformative, and it is considered as one of the main pillars of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (

Hecklau et al. 2016). The rise of large language models (LLMs) has introduced both exciting possibilities and significant challenges to theological and religious instruction (

Papakostas 2025). AI offers both opportunities and risks by providing new subjects and tools for theological study while introducing ethical concerns—from job displacement and worker commodification to plausible near-future scenarios involving its role in worship, spiritual and formative counseling, and the reshaping of cultural and religious understandings of the human person and humanity’s future (

Graves 2024). In the context of the Roman Catholic Church, this technological shift offers new avenues for

locus theologicus and

nouvelle théologie, while also raising critical questions about its role in the contemporary world (

Rahner 1979). The rapid development of AI prompts questions about whether AI could bear the

imago Dei (image of God), challenge the uniqueness of human beings, or function as a companion within human communities (

X. Xu 2024). GenAI encompasses technologies capable of producing human-like content, such as images, text, and music, by interpreting user-provided textual prompts (

Bandi et al. 2023;

O’Dea 2024). In particular, GenAI text-to-image models allow individuals to create complex visual representations of abstract concepts, potentially transforming religious pedagogy (

O’Dea 2024;

Kawka 2025). However, the rapid expansion and widespread adoption of LLMs has raised significant ethical and societal questions (

Van de Poel and Royakkers 2011;

Bandi et al. 2023;

O’Dea 2024;

Kawka 2025).

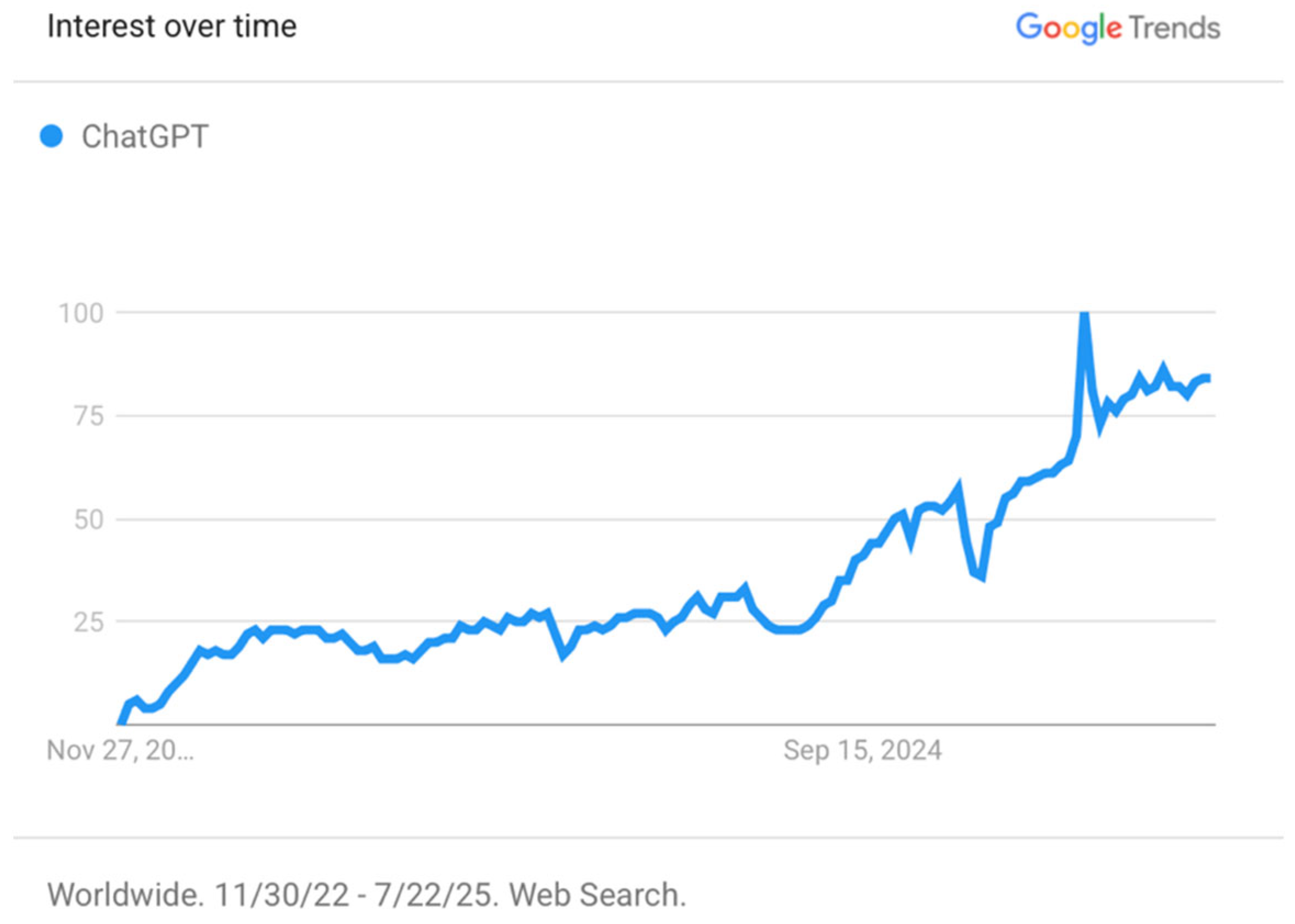

GenAI refers to a class of advanced AI models capable of creating original content—ranging from text and images to videos and problem-solving strategies—demonstrating a level of creativity and adaptability that closely mirrors human output (

He et al. 2025;

Kawka 2025). The adoption of GenAI technologies has expanded rapidly since the early 2020s, largely propelled by breakthroughs in transformer-based neural network architectures, particularly through the advancement of large language models (LLMs) (

O’Dea 2024). These developments have given rise to a range of generative tools, including conversational agents like ChatGPT (GPT-4o), Copilot, Gemini, Grok, and DeepSeek; text-to-image systems such as Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, and DALL·E; and, more recently, text-to-video models like Veo and Sora. Major technology firms—including OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta AI, Microsoft, Google, DeepSeek, and Baidu—have been at the forefront of driving innovation in this rapidly-evolving field (

Pahuja and Singh 2025;

Kawka 2025;

Papakostas 2025).

The Philippines, an archipelagic nation in Southeast Asia, recorded a total household population of 108,667,043 in the 2020 census (

Philippine Statistics Authority 2023). A significant majority of the population—78.8 percent, or approximately 85.6 million individuals—identify as Roman Catholic, reflecting the country’s deep-rooted Catholic heritage. Within this context, Filipino students have increasingly adopted AI in higher education settings. A recent survey conducted by

Instructure (

2025) reported that 93 percent of educators in the Philippines highlight the importance of strengthening technological infrastructure to effectively support lifelong learning initiatives. Additionally, 63 percent of Filipino students use generative AI chatbots like ChatGPT to generate texts, while 58 percent use it for translation tasks. Some 55 percent of students also seek assistance from AI-powered platforms to explain difficult concepts, while 52% rely on them to summarize academic articles (

Instructure 2025).

Despite the growing interest in AI’s role in the Philippine context, its specific implications for Catholic theological education remain underexplored (

Papakostas 2025).

Kawka (

2025) explored a practical theological inquiry on the use of GenAI and created a multimodal artwork using Dalle-3, Suno, Pika, Luma, Kling, and Firefly.

X. Xu (

2024) distinguish between

imago Dei and

imago hominis, using theological frameworks such as the Reformed tradition’s archetype–ectype distinction to ground the human-AI debates. This study responds to the increasing calls for thoughtful theological engagement with AI by examining the role of personal theological reflection using AI-generated content in Catholic theological education. It investigates how both educators and students might utilize AI-generated imagery as a pedagogical resource to enrich theological insights and foster ethical discernment, particularly through the lens of theological virtue ethics (

Lawler and Salzman 2013). The central hypothesis of this paper is that AI is not a substitute for all human tasks. However, the use of AI holds potential for theology, catechetical and religious education.

Drawing from the Catholic intellectual tradition, this research investigates how AI-assisted symbolic representations of faith and spirituality can facilitate personal theological reflection, revealing dimensions of the theological virtues in a digital pedagogical context. It also examines how such reflections intersect with broader concerns around ethical GenAI use in Catholic education.

This study seeks to answer the following research questions:

How can professors and students engage in personal theological reflection through AI-generated images within a Catholic educational context?

What key theological, symbolic, and virtue-centered themes emerge from AI-generated representations of faith and spirituality in such reflective practices?

What are the pedagogical and ethical implications of integrating GenAI tools for personal theological reflection in Catholic religious education, particularly when viewed through the lens of theological virtue ethics?

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

How can professors and students engage in personal theological reflection through AI-generated images within a Catholic educational context? This study adopts a reflective–practical theological framework, employing self-reflective qualitative methods to explore the pedagogical and theological implications of integrating Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools within a Catholic higher education context. Grounded in autoethnography, introspective self-reflection, and qualitative document analysis, the research investigates the researcher’s personal theological reflections as both an educator and theologian. Following

Gläser-Zikuda’s (

2012) model of Self-Reflecting Methods of Learning Research, the study systematically engages in reflective observation to examine how the use of GenAI in theology classrooms has influenced personal theological thinking, pedagogical practices, and ethical considerations. This methodological approach recognizes the subjective, situated nature of knowledge construction, particularly within theological and educational praxis (

Gläser-Zikuda 2012).

3.2. Reflective–Practical Theological Framework

At the core of this study is an innovative theological reflection, conceptualized as a form of practical theology where lived experience serves as a locus for theological inquiry (

Kawka 2025). This involves the conscious examination of personal pedagogical practice, theological assumptions, and emerging insights prompted by the integration of AI-generated content in classroom settings. Personal theological reflection was guided by Catholic theological anthropology, the framework of theological virtue ethics, and the Catholic Church’s evolving engagement with digital technologies (

Kawka 2025).

This study employs written introspective reflection, structured as a learning diary, to document and analyze personal experiences of integrating GenAI tools into theology classes. Drawing from an autoethnographic methodology, the reflections focus on (1) observations during AI-supported classroom activities; (2) personal thoughts, theological questions, and emotional responses evoked by AI-generated images of faith and spirituality; and (3) ethical and pedagogical concerns emerging from the use of AI in Catholic education.

The process of self-observation and introspection involved the following: (1) conscious mental examination of thoughts, theological reasoning, and pedagogical decisions; (2) reflexive analysis of how personal theological perspectives evolved through encounters with AI-generated content; (3) critical engagement with the tension between tradition and technological innovation in Catholic education. This method allows for authentic engagement with personal experience, recognizing the researcher as both subject and analyst.

3.3. Data Sources and Analytical Procedure

The primary data source for this study consists of the researcher’s own reflective journal entries and experiment, developed over several months of engaging with commonly used Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) tools—including ChatGPT, Canva, Meta AI, Deep AI, and Gencraft—within the context of theology classroom praxis. These reflections were integrated in the course syllabus and course discussion within LCFAITH: Faith Worth Living, a core introductory theology course offered at a Catholic university in the Philippines. This course aims to explore faith and spirituality.

The reflective process involved using GenAI tools to generate symbolic representations of core theological themes aligned with the course syllabus. Specific prompts were designed to correspond to major thematic areas, as illustrated in

Table 1.

The AI-generated images were then used as stimuli for personal theological reflection (

Kawka 2025). Each journal entry documented the process of prompt design, image generation, immediate theological reflections on the resulting images, and subsequent pedagogical insights and ethical considerations. The reflections critically engaged the symbolic representations, relating them to Catholic theological principles and the lived realities of Filipino students in a pluralistic educational setting (

Papakostas 2025). As such, faith takes many forms in the way people live and express it.

O’Collins (

2011) identifies three theological styles. The academic style seeks truth through engagement with writings from the past. The practical style seeks justice by listening to the poor and the suffering on matters of faith, doctrine, and morality. The prayerful style seeks divine beauty, fostering hope for the final future through public worship. Each style, when isolated, risks imbalance, yet together they complement one another. The same applies to the dimensions of faith. Faith must be holistic.

The analysis followed a systematic thematic coding procedure to identify key theological, symbolic, and pedagogical themes emerging from the data. This involved initial coding of the reflective entries to surface emergent concepts and theological motifs. Thematic categorization followed, focusing particularly on recurring ideas related to the theological virtues, as well as patterns in symbol interpretation and ethical considerations. These themes were then synthesized and interpreted within the broader context of Catholic pedagogical principles and theological frameworks.

To ensure analytical rigor, informal peer debriefing with colleagues in theology and religious education was employed as a form of expert validation. This iterative process strengthened the internal consistency and credibility of the findings. Through this methodology, the study seeks to articulate how AI-generated content can catalyze personal theological reflection and pedagogical innovation in Catholic higher education, while simultaneously raising critical ethical questions regarding technological mediation in faith formation (

Papakostas 2025).

3.4. Limitations and Reflexivity

This study acknowledges its inherently subjective and context-bound nature, given its reliance on personal theological reflection and autoethnography. Several potential biases are inherent in the approach. These include the researcher’s position as a Catholic theologian and educator, pre-existing theological commitments that may influence interpretation, and the experimental and rapidly evolving nature of generative AI technologies. Nevertheless, deliberate reflexivity served as a methodological safeguard throughout the study (

Bunton 2019). Continuous self-examination and critical awareness of personal biases and positionality were maintained during both data collection and analysis, allowing the researcher to engage critically with the theological and pedagogical implications of AI integration (

Bunton 2019).

3.5. Hypothesis

This study is guided by the hypothesis that Generative Artificial Intelligence introduces both creative opportunities and ethical challenges for Catholic theological education. Specifically, AI-generated content has the potential to serve as a catalyst for personal theological reflection through novel visual–symbolic representations of faith and spirituality. Furthermore, it prompts a re-examination of core theological virtues in light of technologically-mediated forms of meaning-making. At the same time, the use of AI raises significant pedagogical and ethical concerns, particularly regarding authenticity, academic integrity, and the role of human agency in theological formation (

W. Xu 2019;

Ng et al. 2021). In this context, GenAI tools are conceptualized as potential resources for theological exploration and pedagogical innovation within Catholic higher education. AI is not a substitute for theological instruction but a tool to deepen theological understanding.

4. Results

What key theological, symbolic, and virtue-centered themes emerge from AI-generated representations of faith and spirituality in such reflective practices? To explore how Artificial Intelligence can support theological reflection and instruction, five generative AI tools were used to produce artistic representations of faith, each based on a specific prompt aligned with a thematic focus from course modules in Catholic theological education. The tools—ChatGPT, Canva, Meta AI, Deep AI, and Gencraft—were prompted to visually represent distinct dimensions of faith, corresponding to key theological themes. ChatGPT was tasked with generating an image of “faith as trusting,” Canva with “faith as believing,” Meta AI with “faith as praxis,” Deep AI with “faith as dialogue,” and Gencraft with “faith as synthesis.” These outputs were then analyzed for their theological and pedagogical implications in the classroom setting.

4.1. Theme 1: Faith as Trusting

The first image depicts a praying woman before a radiant cross, generated via OpenAI’s ChatGPT platform (

OpenAI 2025). It symbolizes faith as active trust (

fiducia) grounded in relationship rather than mere belief. The image portrays faith not as an abstract concept but as an active, trusting posture. The young woman, depicted in humble prayer before a rugged cross, embodies the act of surrender and dependence. Her bowed head and clasped hands visually represent submission and reliance—central aspects of faith as trusting. The radiant glow behind the cross emphasizes divine presence and assurance, illuminating her darkness with hope. The contrast between her shadowed figure and the luminous cross underscores the theological truth that trusting in God often involves stepping beyond personal understanding into divine illumination.

In systematic theology, faith is commonly divided into three dimensions:

notitia (knowledge),

assensus (assent), and

fiducia (trust). This image powerfully illustrates

fiducia, where faith moves beyond intellectual acknowledgment into relational trust—a surrender to divine will (

Catechism of the Catholic Church 1994).

The cross in the background, radiating warmth and light, can be interpreted theologically as representing Christ’s sacrificial love—central to Christian trust (

Pope Benedict XVI 2009). In this way, the act of prayer in the image is not merely ritualistic but embodies reliance on the God who redeems through the cross (cf. Hebrews 11:1).

4.2. Theme 2: Faith as Believing

The second image generated by

Canva (

2025) depicts a stained-glass window illustrating a radiant dove at the center, traditionally representing the Holy Spirit, surrounded by vibrant rays of light and human figures gazing upwards in reverence. The interplay of light and color emphasizes transcendence, divinity, and spiritual presence. The images in

Canva (

2025) symbolizes faith as believing, focusing on the act of intellectual and spiritual assent to divine realities that transcend empirical proof (

Catechism of the Catholic Church 1994). The upward gazes of Jesus toward the sky signify the act of believing in the unseen and the divine. In Catholic theological understanding, belief involves the conscious acceptance of truths revealed by God, sustained by grace and expressed in worship (

Catechism of the Catholic Church 1994;

Pope Benedict XVI 2009).

The images could serve as catechetical tools: the visual representation embodies the luminous and mysterious nature of faith. The light, as a symbol of the Holy Spirit, reinforces belief as a response to divine revelation and presence. The light filtering through can be read as a metaphor for the grace that enlightens human understanding, guiding believers towards the fullness of truth, much like St. Anselm’s formulation of

fides quaerens intellectum (faith seeking understanding). Thus, faith as believing involves an intellectual assent coupled with an interior openness to divine mystery (

Catechism of the Catholic Church 1994).

4.3. Theme 3: Faith as Praxis

The images from

Meta AI (

2025) are more realistic compared to the first two images. Meta AI thematically categorized the images as “Faith as Praxis.” The multiple panels depict various visual representations: (a) Stepping Forward in Trust shows an individual taking a symbolic step on a luminous pathway, representing active commitment rooted in trust. (b) Path of Conviction illustrates a solitary figure walking through uncertain terrain, evoking the journey of faith lived out amid challenges. (c) Embodied Conviction features hands engaged in acts of service, symbolizing faith expressed through ethical action and solidarity. (d) Practicing Devotion portrays ritual gestures—hands in prayer or offering—highlighting faith as expressed through embodied practices of devotion and worship (

Catechism of the Catholic Church 1994).

From a liberationist perspective, these images reflect the praxis dimension of faith as emphasized in liberation theology and Catholic social teaching: faith not as mere intellectual assent, but as embodied action in the world. Faith is a verb. Theologically, they align with the understanding of faith as a lived commitment—a response to God’s call expressed through works of justice, service, and daily ethical engagement. The images serve as visual catechesis, inviting both theological reflection and practical discipleship (

Catechism of the Catholic Church 1994).

4.4. Theme 4: Faith as Dialogue

The module on faith as dialogue was generated via

Deep AI (

2025), presents a dialogical image featuring a woman and man engaged in conversation. This visual representation embodies faith as dialogue, understood here as an encounter not only with believers of other religions but also with the non-religious. The image, however, falls short of fully expressing the meaning of faith as dialogue from a theological perspective. Applying the four forms of interreligious dialogue articulated by the Vatican (

Pontifical Council for Inter-Religious Dialogue 1991), the image can be analyzed as follows:

Dialogue of Life: The casual, relational posture of the figures represents everyday interactions where mutual respect and shared humanity are expressed.

Dialogue of Action: The image subtly suggests collaborative engagement, as the figures appear to work toward a common understanding or shared goal.

Dialogue of Theological Exchange: The open exchange of ideas symbolized in the image represents the intellectual dialogue that occurs between theologians or scholars of different traditions.

Dialogue of Religious Experience: Though not explicitly depicted, the image can evoke silent, empathetic listening to each other’s spiritual narratives, recognizing the sacred in the other.

Theologically, the image reinforces the Church’s call for dialogue as both a missionary and pastoral imperative in today’s pluralistic world (

Corpuz 2025). Faith, in this sense, is relational, responsive, and open to encounter. AI-generated imagery like this can thus serve as a pedagogical tool to introduce students to dialogical theology and interfaith engagement (

Corpuz 2025).

4.5. Theme 5: Faith as Synthesis

The image of faith as synthesis was generated from

Gencraft (

2025). It depicts a symbolic synthesis of world religions—a visual synthesis of diverse religious symbols (e.g., cross, crescent, om, and dharma wheel) integrated into a unified composition. The image can be analyzed using the theological models of exclusivism, inclusivism, and pluralism (

Race 1986). The image invites critical reflection: From an exclusivist lens, such a synthesis may be seen as problematic, risking the dilution of Catholic doctrinal truth. An inclusivist reading interprets the image as representing seeds of truth present in other religions, fulfilled ultimately in Christ, echoing the Second Vatican Council’s approach. A pluralist perspective might affirm the image as a celebration of equal spiritual paths, each possessing intrinsic salvific value (

Race 1986;

Corpuz 2025).

For theological instruction, this AI-generated image acts as a reflective tool to engage students in comparative theology and interfaith dialogue, helping them critically assess their own positions while appreciating religious diversity. It supports a holistic theology of faith—one that balances fidelity to Catholic teaching with openness to the religious other, fostering an integrative spiritual worldview (

Second Vatican Council 1965).

In synthesis, these AI-generated images demonstrate the capacity of GenAI tools to visualize abstract theological concepts in ways that are pedagogically innovative and theologically rich, serving both as stimuli for personal reflection and as resources for dialogical and contextual theological education. AI must not be seen as replacing the formative, relational, and dialogical nature of theological instruction. Rather, it can serve as a complementary tool that enhances critical reflection, personal engagement, and the creative expression of faith.

The author decided not to include the GenAI images because the legal implications of using generative AI remain unclear, especially in relation to copyright infringement, ownership of GenAI works, and unlicensed content in training data.

Gillotte (

2020) notes that, assuming GenAI works qualify for copyright protection, the central question becomes identifying the rightful copyright holder. The US Copyright Office and several scholars maintain that GenAI cannot hold copyright because it lacks legal personhood (

Gillotte 2020). Other authors propose that copyright might be shared between the human creator and the AI system involved in the process (

Darvishi et al. 2022). To mitigate these legal risks, researchers and creators working with GenAI should ensure compliance with existing laws by relying on licensed training data and establishing mechanisms to verify the origin of generated outputs.

5. Analysis

The integration of GenAI into classroom pedagogy and the interpretation of religious content represents a significant advancement in catechesis and theological education. Unlike traditional approaches that often emphasize rote memorization and the recitation of sacred texts, contemporary models are increasingly characterized by transformative learning in which both educators and learners actively participate in meaning-making processes (

Alkhouri 2024). In this context, Smart’s phenomenological approach offers a valuable framework, advocating for non-judgmental engagement with the lived dimensions of religion—such as myth, ritual, moral frameworks, spiritual experience, and communal practices—prior to critical assessment (

Barnes 2000;

O’Grady 2005).

GenAI can simulate responses, generate content, or analyze texts, but it cannot believe, worship, or love. These are fundamentally relational and spiritual acts rooted in human freedom and divine grace. Therefore, integrating AI into theology classrooms should always point students toward deeper faith, critical thinking, and moral responsibility, not the automation of belief or a reduction in mystery.

5.1. Moral Formation and Virtue Ethics in Theological Anthropology

Viewed through the lens of theological virtue ethics and theological anthropology, the findings of this study highlight that the use of Generative AI within Catholic education is fundamentally a practice of moral and spiritual formation (

Wojtyła 1993;

Pope Leo XIV 2025). Grounded in the understanding that human beings, created in the

imago Dei, are called to live as relational and morally responsible agents, the creative engagement with AI-generated spiritual imagery becomes an act of co-creation that reflects human participation in God’s ongoing work of creation (

Graves 2024). Karol

Wojtyła (

1993) argues that being human goes beyond biological or functional definitions. What defines the human person most deeply is their identity as created in the image of God. Human dignity is grounded in this truth (

Wojtyła 1993).

This process calls for the development of the moral imagination, especially when guided by theological virtues such as faith, hope, and love (

Vallor 2016). Rather than distancing learners from spiritual realities, AI can become a medium through which students are formed in discernment and responsibility, as they thoughtfully navigate questions of representation, meaning, and religious symbolism in a digital environment (

Sison and Fontrodona 2012). The inclusion of theological symbols in the generated images enhances this formative experience, anchoring the outputs within the Catholic sacramental vision. As

Walton (

2014) observes, such symbols are potent because they mediate between the material and symbolic realms, enabling digital images to assume a quasi-sacramental function—awakening awareness of divine presence through visible signs.

The application of virtue ethics in this context foregrounds the significance of character, intentionality, and context in the creation and interpretation of GenAI content (

Alford 2017). In this framework, four foundational AI-related virtues—justice, honesty, responsibility, and care—are essential for ethical engagement, while prudence and fortitude serve as higher-order virtues that enable individuals to resist the subtle psychological and systemic influences that can compromise ethical decision-making (

Hagendorff 2022).

UNESCO’s (

2021) extensive Policy Action Areas—such as data governance, environmental sustainability, gender equality, education, research, health, and social wellbeing—demonstrate a comprehensive ethical vision. This aligns with a virtue ethics framework, particularly the Catholic emphasis on the development of moral character through the theological virtues of faith, hope, and love, and the cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance (

Catechism of the Catholic Church 1994). These virtues guide the ethical use of AI, ensuring it contributes to the common good (

Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace 2004), rather than perpetuating inequality or harm (

Pinckaers 1995).

Ultimately, integrating GenAI into Catholic theological instruction calls for a pedagogy that forms both the intellect and the moral imagination. This requires an intentional focus on virtues that affirm the dignity of the human person and the sacredness of the creative task, positioning AI not as a substitute for human moral agency but as a tool that, when guided by virtue, can enhance theological reflection and deepen spiritual formation (

Hagendorff 2022).

Pope Francis (

2015) and

Pope Leo XIV (

2025) emphasize that rapid technological progress requires an anthropological vision and strong ethical regulation to safeguard human dignity and sustain life’s meaning.

5.2. Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence

The paradigm of Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HCAI) emphasizes the integration of AI systems within the broader context of human life, acknowledging that technological tools must serve persons and communities rather than displace them (

Riedl 2019;

Yang et al. 2021;

X. Xu 2024;

Zhang et al. 2025). This model calls for the development of transparent, intelligible, and relational AI—systems that honor the complexity of human contexts and promote mutual understanding between users and machines (

Riedl 2019). The shortcomings of earlier AI models—chiefly their failure to adapt to human expectations and respond to the realities of lived experience (

W. Xu 2019)—underscore the need for a design approach that places human dignity, freedom, and responsibility at the center of technological innovation (

Guo et al. 2021;

Qadir et al. 2022).

In the context of theological instruction using GenAI content, the principles of HCAI offer a critical framework for ethical, pedagogical, and theological engagement (

Qadir et al. 2022). Applying HCAI to the analysis and discussion of AI-generated images of faith requires attention to human needs, transparency, and value alignment. Using a need-design response approach (

Qadir et al. 2022;

Xu et al. 2023), instructors can identify students’ theological and cultural contexts, ensuring that AI-generated content addresses their intellectual, spiritual, and moral development rather than imposing abstract or culturally detached representations. Transparency and explainability are equally vital, particularly when interpreting symbolic imagery generated by AI tools such as ChatGPT or Canva (

Monarch 2021). Instructors and students should be able to understand how AI systems produce these images to foster critical reflection and avoid blind acceptance of algorithmic outputs. Moreover, theological education must uphold highest ethical standards that prevent bias and ensure inclusivity, particularly in diverse and multireligious classrooms (

Auernhammer 2020;

Qadir et al. 2022). Generative AI tools must be carefully curated to avoid the reproduction of harmful, discriminatory, or offensive content—especially given their global sociocultural reach (

Riedl 2019). Human-centered regulations and policies, including sensitivity to intellectual property rights and cultural representation, are necessary to guide AI use in religious pedagogy (

Qadir et al. 2022). Finally, fostering AI literacy among theology educators and students is essential for meaningful collaboration (

Corpuz 2023). This involves the ethical discernment to evaluate, critique, and integrate AI content in ways that support rather than replace human theological reflection (

W. Xu 2019;

Ng et al. 2021). Thus, HCAI in theological instruction affirms the dignity of the human person as the central agent of meaning-making in the digital age.

UNESCO (

2021) affirms that “The protection of human rights and dignity is the cornerstone of the Recommendation, based on the advancement of fundamental principles such as transparency and fairness, always remembering the importance of human oversight of AI systems.” This ethical orientation resonates deeply with theological ethics, particularly within the Catholic tradition, that grounds moral discernment in the inviolable dignity of the human person (

Second Vatican Council 1965). The emphasis on human oversight echoes the theological principle of stewardship, wherein human beings, made in the image of God (cf Genesis 1:26–28), are entrusted with responsibility over creation and technological advancement, exercising prudence and accountability (

Pope Francis 2015).

5.3. Theological Esthetics and Spirituality

In Catholic tradition, visual representations have long served as tools to support prayer and help believers recognize the presence of divine grace (

Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments 2001). Religious images have historically functioned as aids to devotion, guiding the faithful in directing their prayers toward sacred figures (

Abogado 2006;

del Castillo et al. 2021). The Catholic Church emphasizes that authentic forms of popular devotion, including the use of sacred images, are not in conflict with the central role of the Sacred Liturgy but instead help nurture the faith of the people and prepare them for full participation in the Church’s sacramental life (

Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments 2001). In this context, AI-generated images of religious themes can be viewed as a contemporary expression of popular devotion. When used thoughtfully, such digital creations may supplement traditional practices by providing new ways for students and younger generations to engage visually and spiritually with their faith (

Pope Francis 2015). The synthesis AI-generated imagery—particularly within the context of Christian faith and theological esthetics—revealed a rich array of themes that articulate diverse theological, symbolic, and affective dimensions of spirituality. These symbolic representations embody deeply personal and contemporary expressions of belief, identity, and transcendence (

Pinckaers 1995;

Alford 2017).

Esthetic theology engages with modes of knowing that are grounded in feeling, imagination, and embodied experience. It investigates how human consciousness perceives and responds to the divine through esthetic forms, which can serve as mediators of revelation and catalysts for spiritual transformation. As

Viladesau (

1999) describes, esthetic theology draws upon the esthetic realm not only for its expressive language and content but also as a methodological and theoretical framework. This approach merges theology with creative and beautiful expression—termed

theopoiesis—and with the interpretive theories that support such imaginative theological discourse, or

theopoetics. Drawing from

Brown (

2000), the integration of these symbols illustrates how religious engagement operates through esthetic discernment—where taste, feeling, and imagination converge.

Brown (

2000) suggests that esthetic experience is central to spiritual life, shaping both personal piety and communal worship. The theological meaning embedded in these artworks is inextricably linked with sociocultural and esthetic elements, identities, and spiritual sensibilities (

Brown 2000).

This dynamic becomes particularly complex in the context of GenAI religious images. While Generative AI can synthesize diverse Christian styles and iconographies, it lacks the theological and esthetic capacity to discern the symbolic appropriateness of what it produces. As

Viladesau (

1999) cautions, revelation is always susceptible to misinterpretation. Without careful theological framing, symbols risk becoming distorted, mythologized, or even idolatrous.

Tillich’s (

1955) warning about the “demonization” of symbols—where the sign becomes ultimate rather than pointing to the transcendent—serves as a critical reminder of the theological responsibilities involved in interpreting religious esthetics in the age of AI. Rather than viewing AI as external or neutral, the critique suggests a more integrated view—where AI is seen as co-constitutive of human self-understanding and social relations (

Graves 2024;

Papakostas 2025).

Contemporary discussions on spirituality have become increasingly multifaceted and, in some cases, conceptually ambiguous. As

Chmielewski (

2017) notes, while the term “spirituality” enjoys widespread usage in modern discourse, its interpretations vary significantly across cultural and philosophical contexts. This plurality has given rise to what may be described as a “new spirituality,” encompassing a range of perspectives—including atheistic or non-theistic spiritualities and psychologically grounded understandings of spiritual experience. Despite their divergent foundations, these emerging forms share a common emphasis on the human capacity for transcendence—an intrinsic orientation toward meaning, connectedness, and interior depth that extends beyond purely material concerns (

Graves 2024;

Papakostas 2025).

5.4. Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence in the Age of the New Evangelization

A symbol functions as a tangible representation of a sacred truth or theological mystery that transcends complete human comprehension (

Geertz 1971). These truths, central to the life of faith, are often ineffable and elusive in their full depth. Through symbolic expression, believers are invited to contemplate dimensions of divine reality and to engage more profoundly in their spiritual journey. Symbols serve as focal points for prayer and reflection, orienting the faithful toward the transcendent and the eschatological horizon of belief. Etymologically derived from the Greek

symballein, meaning “to bring together,” the concept of the symbol implies a convergence of the visible and invisible, the finite and the infinite. For instance, the sign of the cross operates both as an external identifier of Christian faith and as an affirmation of belief in the Triune God, encapsulating key doctrinal tenets within a performative and devotional act (

Pope Benedict XVI 2009).

In

Evangelii Gaudium,

Pope Francis (

2013) underscores the importance of the

Way of Beauty as a powerful pathway for evangelization. He calls upon each local Church to embrace the arts as a vital medium for proclaiming the Gospel, urging the faithful to draw upon both the rich artistic heritage of the Christian tradition and the evolving forms of contemporary cultural expression.

Pope Francis (

2013) emphasizes the need to communicate the faith through a renewed “language of parables,” capable of engaging diverse audiences across cultural and generational boundaries. This involves courageously exploring new signs and symbols, seeking out forms of beauty that may not resonate with evangelizers themselves but possess deep appeal for others, particularly within emerging cultural contexts (

Pope Francis 2013). The study’s findings suggest that AI-generated symbols, shaped by the meeting of faith and spiritual imagination, present new possibilities for a renewed evangelizing mission in the age of AI as a “new social question” that calls for the Church’s ancient and contemporary wisdom. Following the spirit of his namesake,

Pope Leo XIV (

2025) has oriented his pontificate toward addressing the

rerum novarum or “new things.”

These digitally produced images reflect both traditional theological motifs and novel esthetic expressions, revealing how AI can become a tool for the creative mediation of the Gospel message (

Pope Francis 2013). While AI lacks the capacity for spiritual discernment, its ability to generate visually compelling representations of theological concepts opens up new possibilities for dialogue, new forms of catechesis, and new theological pedagogy, particularly among digitally native generations (

Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith 2025;

Pope Leo XIV 2025). AI technologies may contribute to the New Evangelization by facilitating a form of theological imagination that is culturally relevant, esthetically engaging, and accessible across multiple platforms. These findings affirm Pope Francis’s vision of evangelization as a dynamic and creative process, one that is attentive not only to doctrinal fidelity but also to the cultural languages and symbolic vocabularies through which faith is most effectively expressed and received in the contemporary world (

Pope Francis 2013).

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study offers a synthesis of GenAI images reflecting images of faith. While this approach provides valuable insight into the pedagogical and theological potential of GenAI within a religious education context, several limitations must be acknowledged.

First, the study draws from a relatively small sample GenAI images, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The theological and symbolic interpretations presented here are influenced by cultural, educational, and generational contexts—primarily from within Roman Catholic frameworks—necessitating caution when extrapolating these results to broader applications (

Ignatowski et al. 2024). Theological ethics can enrich and critically accompany university policies by rooting the implementation of AI ethics in a vision of human dignity, social justice, and ecological responsibility, all central to Catholic social teaching and relevant to the moral evaluation of emerging technologies (

Pinckaers 1995;

Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace 2004).

Second, generative AI systems, such as those employed in this study, are prone to producing “hallucinations” (fabricated or misleading outputs) and may reproduce entrenched biases present in their training data (

X. Xu 2024;

Zhang et al. 2025). As noted by

McCormack et al. (

2024), large-scale analyses of image generators like Diffusion DB and Midjourney reveal a tendency toward visual clichés and stylistic homogenization, privileging hyper-estheticized, often-gendered, or fantasy-based representations. Such biases risk flattening theological nuance and may inadvertently propagate reductive or distorted images of the sacred (

Kawka 2025). These false attractions and illusions continue to block people from truly experiencing deep truth and beauty. They also prevent people from knowing the beauty and wisdom of God (

Al-Kassimi 2023). Moreover, as

Quaranta (

2023) cautions, the emergence of “digital kitsch”—overproduced, visually striking yet theologically superficial imagery—presents a significant challenge for educators and theologians. The task of discerning meaningful theological symbolism from mere esthetic imitation remains essential for scholars engaging with the intersection of AI and religious education. This challenge also extends to the proliferation of misleading visual content online, particularly in the form of so-called “deepfakes” and “hallucinations” (

Riedl 2019;

Yang et al. 2021;

X. Xu 2024;

Zhang et al. 2025;

Kawka 2025). Hence, there is an urgent need to produce a theologically-informed code of ethics among higher educational institutions to respond to the ethical questions surrounding the use of AI and GenAI.

Third, the deployment of AI in the classroom must be grounded in a robust ethical framework (

Porter 1994). In the context of Catholic theological education, virtue ethics provides a critical lens for discerning the appropriate use of AI tools. For

MacIntyre (

1984), the virtues of the Christian tradition are visible and embodied in the community’s practices. Within the realm of Artificial Intelligence, ethical concerns encompass the moral responsibilities of both AI technologies and their developers (

Siau and Wang 2020). Generative AI raises significant ethical challenges that must be addressed to ensure its responsible use (

Gillotte 2020;

Guo et al. 2021). These challenges include the potential generation of harmful or inappropriate content, the perpetuation of biases (

Riedl 2019;

Yang et al. 2021;

Chan 2022;

X. Xu 2024;

Zhang et al. 2025) embedded within algorithms, risks of over-reliance on AI systems, the misuse of AI outputs, threats to privacy and data security, and the exacerbation of existing digital inequalities. These ethical issues highlight the need for careful human oversight and value-centered design in the development and deployment of Generative AI tools (

Gillotte 2020;

Borenstein and Howard 2020). Therefore, it is essential to HCAI to uphold the principle of collaboration between humans and AI systems.

Future research should examine the effects of GenAI on students’ spirituality, faith, and religiosity. Professors need to verify that images comply with university guidelines and address legal and ethical issues. Studies could also compare different artistic styles in a systematic way. These steps will help develop a broader understanding of how digital artworks are perceived in higher education (

Gillotte 2020;

Borenstein and Howard 2020). Perspectives on human nature and AI’s societal impact range from optimistic to pessimistic, often shaped by the specific risks and opportunities addressed in an argument (

Graves 2024;

Papakostas 2025). Moving past the AI–human divide, questions of reality, physicality, metaphysics, and interpretive frameworks remain. Future theological research can assess AI through an ethical lens, considering how generative AI might influence human suffering, flourishing, and the mental health of students.

The use of AI and LLMs need not stand in opposition to Catholic theology and religious education. Rather, their integration can be approached in a spirit of “accompaniment,” “dialogue,” and “encounter”—especially important in this period of the Church’s synodal journey (

Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith 2025). Emerging technologies like AI should not be seen as competitors to the mission of evangelists and catechists, whose work is fundamentally grounded in personal, embodied, and relational encounters. AI cannot—and is not intended to—replace the irreplaceable gift of human presence or the depth of authentic empathy (

Wang 2021). Instead of dismissing these technologies or exploiting their limitations for superficial recognition, a more constructive approach is to engage them critically and responsibly, recognizing both their possibilities and boundaries. Positioning AI as an aid rather than a substitute for human formation and pastoral care enables Catholic educators and ministers to integrate technology as a complement to, rather than a distortion of, the uniquely human vocation of religious education and evangelization (

X. Xu 2024;

Graves 2024;

Papakostas 2025).

7. Conclusions

As GenAI becomes more integrated into daily life, its influence on theology, religious education, and spiritual formation calls for thoughtful ethical engagement. This study contributes to the growing field of AI and theology by showing how GenAI can serve as a creative medium for instructors to express and reflect on their spiritual experiences. The tools ChatGPT, Canva, Meta AI, Deep AI, and Gencraft were used to generate visual representations of distinct dimensions of faith aligned with key theological themes. ChatGPT was tasked with generating an image of “faith as trusting,” Canva with “faith as believing,” Meta AI with “faith as praxis,” Deep AI with “faith as dialogue,” and Gencraft with “faith as synthesis.” The findings emphasize an urgent need to produce a theologically-informed code of ethics among higher educational institutions to respond to the ethical questions surrounding the use of AI. The principles of HCAI offer a critical framework for ethical, pedagogical, and theological engagement.

Theology provides a framework within the ethical dimensions of AI, especially in how technology can support the cultivation of human agency, privacy, transparency, fairness, societal and environmental wellbeing, and accountability—both on the part of the users (students) and the developers (AI creators and educators). The promise of AI in ethical formation can only be fully realized when approached with highest ethical standards, creative imagination, and a commitment to the dignity of the human person, which is the central theme of Catholic social teaching and magisterium. This study provides new insights into the ethical use of AI and GenAI in theological education, and it highlights the importance of considering theologically-informed ethics.