Abstract

The study of the relationship between religion and newspapers embodies a well-established research field. However, relatively few studies focus on interfaith dialogue in the press. Against this backdrop, important questions about the manifestations and dynamics of interreligious dialogue in newspapers remain largely unexplored. Adopting a quali-quantitative approach and a topic-detection methodology, the research analyzes 1186 articles from four Italian newspapers (Corriere della Sera, Il Giornale, La Stampa, Il Mattino di Padova) mentioning interreligious dialogue between 2010 and 2023. The research seeks to answer the question: how do major Italian newspapers discursively construct and represent the topic of interreligious dialogue in their coverage? The results identify five representations of interreligious dialogue in the Italian press, each interconnected and/or partially overlapping. Specifically, the analysis of the newspapers’ articles reveals: (i) a broad but fragmented and episodic representation of interreligious dialogue, highlighting a lack of systematic or sustained discussion on the topic; (ii) a hegemonic presence of the Catholic Church in the various representations of interreligious dialogue, expressed through the Pope, Church organizations, and leaders; (iii) a widespread portrayal of Islam as a “challenging religion”, associated with the idea of a “clash of civilizations” and issues surrounding the integration of Muslim immigrants; (iv) a general focus on traditional Abrahamic religions in the representation of interreligious dialogue, which tends to exclude other religious minorities.

1. Introduction: Interreligious Dialogue and Newspapers

Religion and mass media have long been intertwined, shaping and reflecting public discourse. The media, often referred to as the “Fourth Estate”—a term attributed to Burke in 1787 (Macknight 1858)—exerts significant influence on how religion is represented and interpreted in the public sphere. As Pace (2011) notes, both the discourse of God and discourse about God circulate within mediated environments. This intersection has become a well-established field of research (De Vries and Weber 2001; Hosseini 2008; Lövheim 2019; Meyer and Moors 2005; Stolow 2005; Winston 2012), exploring how religious narratives, symbols, and identities are constructed, negotiated, and contested in the media (such as television, radio, print journalism, and digital platforms), and how contemporary religions and religious experiences may shape media.

There are still relatively few studies focusing on interreligious contacts and dialogue in mass media (Klinkhammer 2020; Maweu 2021; Neumaier and Klinkhammer 2020; Pons-de Wit et al. 2015). While media play a crucial role in shaping perceptions of interreligious engagements and encounters, most research has concentrated on representations of individual religions rather than on their interactions. The digital environment offers new spaces for encounters, exchanges, and conflicts between religious groups, yet this dimension remains under-explored. However, despite this growing social interest in interreligious dialogue (Giordan and Lynch 2019), fewer studies have concentrated specifically on the representation of interfaith dialogue within the mass media (Klinkhammer 2020). Given the increasing importance of religious diversity in contemporary societies (Giordan and Pace 2014), the ways in which interreligious dialogue is presented in newspapers can significantly influence public discourse and shape societal attitudes toward religious coexistence.

Open questions remain regarding interreligious dialogue in mass media, particularly in the press. Media outlets, including newspapers, can significantly influence interreligious relations (Herbert 2011), shaping public perceptions through their framing of religious topics. A key issue concerns how both majority religions and religious minorities are represented in the media (Bantimaroudis 2007; Wright 1997). These representations can either promote tolerance and mutual understanding or, conversely, reinforce stereotypes and contribute to processes of exclusion and marginalization (Klinkhammer 2020; Poole 2002). Understanding the power of media discourses is essential for assessing their role in fostering constructive interreligious engagements or perpetuating societal divisions.

Against this backdrop, the present research seeks to address the above gap by adopting a mixed-methods approach that combines qualitative and quantitative content analysis with a topic-detection framework. The study aims to uncover patterns in media coverage, identify prevailing representations, and assess the extent to which interfaith dialogue is depicted as a constructive or contentious issue in Italian journalism. By examining thousands of articles published between 2010 and 2023 across four Italian newspapers—two national (Corriere della Sera and Il Giornale) and two local (Il Mattino di Padova and La Stampa)—this study provides an in-depth exploration of how interreligious dialogue is depicted in the Italian press. In short, the research employs a quali-quantitative content analysis to identify recurring themes and narratives in newspaper coverage of interreligious dialogue. More precisely, it seeks to answer the question: how do major Italian newspapers discursively construct and represent the topic of interreligious dialogue in their coverage from 2010 to 2023?

After introducing the notion of media representation, Section 2 will show how the topic-detection approach enables the systematic categorization of themes emerging from the data, providing insight into how newspapers construct different representations of interfaith dialogue. This analysis will categorize, extract, and examine the content to highlight key themes and concepts by grouping them using a “flexible coding” approach (Deterding and Waters 2021). Categories will be developed deductively, based on typologies and patterns found in the scientific literature, as well as inductively, to capture new ideas emerging from the empirical data. The analysis—including figures and visual data—will be carried out using software for statistical analysis of textual data.

Section 3 presents the results of our topic modeling analysis, which identified five distinct thematic clusters within the corpus of newspaper articles concerning interreligious dialogue in Italy. Each topic is defined by a specific set of co-occurring words, forming what we term “lexical worlds” that reveal differentiated patterns of meaning and framing. These topics not only delineate the ways in which interreligious dialogue is constructed in the Italian press but also reflect diverse editorial agendas and discursive strategies. Through a detailed exploration of each topic, we uncover the varied lenses through which the media interpret and represent the interplay between religions and society. From representations of Islam as a sociopolitical issue to formal Catholic discourses and the symbolic leadership of Pope Francis to grassroots initiatives and institutional frameworks, the five topics offer a multifaceted view of interreligious dialogue. Moreover, the semantic mapping and the association of topics with specific newspapers shed light on the political positioning of each outlet, revealing how editorial choices shape public discourse.

Section 4 draws together the key insights from the analysis, offering a critical reflection on the ways in which interreligious dialogue is represented in the Italian press. Building on the empirical evidence and thematic discussion presented earlier, this concluding part aims to synthesize the main findings, identify broader implications, and outline possible avenues for future research. The discussion is organized around four central points that emerged from the study: the episodic and fragmented nature of interreligious coverage; the central role of the Catholic Church in shaping public discourse; the securitarian and often conflictual portrayal of Islam; and the marginalization of non-Abrahamic religious communities. These elements are interpreted in light of existing scholarship and contextualized within the Italian media landscape, highlighting how editorial lines influence the visibility and framing of religious pluralism. The section also engages with the limitations of the study—particularly the scope of the corpus—and suggests directions for expanding the research, including the inclusion of regional and confessional newspapers.

To conclude, through both quantitative and qualitative analysis, the article investigates the visibility, framing, and discursive patterns associated with interreligious dialogue in Italian newspapers. It aims to shed light on the broader relationship between media representations and interfaith dialogue, offering insights into how the press—or more broadly journalism—shapes public discourse on interfaith relations in the Italian peninsula.

2. Research Approach, Methodology, and Data

The present study employs a quali-quantitative approach to examine how specific lexical patterns construct different media representations of interreligious dialogue across Italian newspapers. From a theoretical standpoint, this study draws on the notion of media representations as socially constructed mediated processes. As Stuart Hall (1997) argued, representations are not mere reflections of reality but are actively produced through systems of meaning that shape how events, identities, and social phenomena are understood. Within this framework, media do not neutrally depict interreligious dialogue but rather frame it through particular linguistic choices, narrative structures, and symbolic codes that reflect broader cultural and political stances. In line with Hall’s perspective, media texts can be seen as the result of intentional production strategies that audiences may interpret differently depending on their cultural positions.

In this regard, scholars such as Van Dijk (1991, 1998) have emphasized how media discourse plays a central role in the reproduction of social power and inequality, particularly in the portrayal of ethnic and religious minorities. Through discourse analysis, van Dijk shows how seemingly neutral journalistic language often embeds implicit biases that shape public perceptions. According to Entman’s approach (Entman 1993, 2007) to the analysis of media coverage, moreover, framing can be seen as a way of embedding events within an interpretive context that shapes how the public understands their meaning. This perspective frames media portrayals of interreligious dialogue as discursive arenas where different narratives are negotiated, with some actors, such as the Catholic Church, being positioned as normative voices (Aroldi et al. 2024). In short, these theoretical approaches (namely those of Hall, van Dijk, and Entman) guide our analysis of how newspapers construct and negotiate the representation of interfaith dialogue in the Italian context.

From a methodological viewpoint, our research adopted a quanti-qualitative approach (Creswell and Clark 2011) based on topic-detection (Tuzzi 2024) applied to a corpus of around one thousand articles. Specifically, we applied a topic-detection method to classify text segments into distinct topics. For this purpose, we employed the algorithm developed by Reinert (1983), implemented in the R-based version of Iramuteq (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires) (Ratinaud 2014; Ratinaud and Marchand 2015). This automated classification of text segments proved valuable for identifying recurring themes, what Reinert (1993) refers to as “lexical worlds”, characterized by distinct vocabularies that can be interpreted as latent variables, thereby offering deeper insights into the textual data.

The analysis followed a multi-step procedure (Nicoli et al. 2024; Sbalchiero 2018). Initially, the corpus of articles was imported and segmented into elementary context units (ECUs), which consist of text segments approximately 50 words long, with punctuation preserved. The method then identifies patterns of word co-occurrence within each ECU by creating a contingency table (“words × units”), which forms the foundation for measuring similarities among the ECUs. To group these units into distinct thematic clusters, the algorithm applies a descending hierarchical cluster analysis, relying on successive Correspondence Analyses (Greenacre 1984; Lebart et al. 1984) and using the chi-square distance metric (Reinert 1983). The classification ultimately produces a set of semantic clusters (topics defined by groups of words) that we interpreted by examining the text segments most representative of each cluster, as detailed in the following sections. For this study, the identified topics were further analyzed to determine their association with the categorical variable “newspaper”, enabling us to interpret semantic classes in terms of “who says what”. In other words, if a topic is predominantly addressed by a specific newspaper, significant chi-square values and positive residuals signal a strong link between that newspaper and the topic.

Our research focuses on the annual coverage of relevant articles across four newspapers from 2010 to 2023. This choice reflects an exploratory approach, both in terms of the selection of the newspapers and the time frame, which we consider preliminary. Future developments of the study should expand the analysis to include a broader range of media and a more extensive chronological scope. As for article selection, we applied a relevance criterion based on the explicit presence of content and references to interreligious or interfaith dialogue (“dialogo interreligioso”). Moreover, while textual corpora represent raw data, our analyses will rely on the shadow dataset principle, which involves the use of pre-processed data that preserve selected linguistic features but do not allow for the reconstruction of the original texts. This approach aligns with ethical and methodological best practices in computational linguistics and privacy-preserving text analytics (Veluru et al. 2014).

Table 1 summarizes the total number of articles analyzed, amounting to 1186 in total, distributed by year and newspaper: 392 from Corriere della Sera, 157 from Il Giornale, 499 from La Stampa, and 138 from Il Mattino. The choice to focus on traditional print media, particularly newspapers, is based on the fact that—unlike social media or blogs—they are selective and guided by journalistic ethics aimed at portraying the world. Newspapers thus represent a privileged site to observe how interreligious activities are represented and discussed, providing an informed sense of the interests and concerns that shape the public sphere. In this respect, the selection of the above newspapers was made with the specific intention of capturing a diversity of editorial perspectives on interreligious dialogue, representing viewpoints across the political spectrum, from left to center to right. This choice aims to account for potential differences in framing, emphasis, and narrative strategies shaped by the newspapers’ orientations, thereby allowing for a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of how interreligious dialogue is portrayed in the Italian media landscape.

Table 1.

Selected articles referring to interreligious or interfaith dialogue.

The distribution of relevant articles is uneven across the selected newspapers. This discrepancy, despite the application of a uniform selection criterion, suggests that certain newspapers may give more visibility to the topic of interreligious dialogue than others. On the one hand, this highlights the varying degrees of editorial attention dedicated to the subject in general, and on the other, it further justifies the inclusion of diverse newspapers, as it enables us to explore how the salience and treatment of interreligious dialogue may vary depending on each newspaper’s orientation and editorial priorities.

Finally, the findings are analyzed and contextualized through the lens of social scientific studies on religion and media, interreligious dialogue in the press, and religion within the Italian context.

3. Findings and Discussion

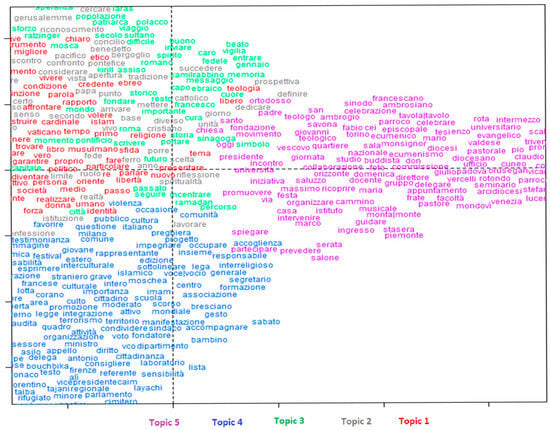

The analysis led us to identify five distinct topics emerging from the corpus of articles. Each topic is characterized by a specific vocabulary—sets of words frequently associated with one another—allowing us to interpret them as different forms of thematic structuring. These topics outline diverse ways in which newspapers construct and represent the theme of interreligious dialogue. Each topic contains, in fact, a unique thematic focus that reflects distinct orientations, highlighting not only the multiplicity of discursive strategies but also the varying editorial approaches and emphases across the newspapers analyzed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The topics or representations of interreligious dialogue.

By examining the figure, the identified topics, or “lexical worlds”—each one marked by a specific constellation of strongly associated words—embody diverse media representations or differentiated modes of framing interreligious dialogue across the selected newspapers. Each topic not only reflects a thematic orientation but also reveals underlying editorial lines and discursive strategies related to religion, identity, and intercultural dynamics in Italy.

The first topic (red), which we label “the question of Islam in Italy”, is primarily concerned with Islam as a sociopolitical issue within the Italian context. By examining the words most strongly associated with the topic—such as Islam (“islam”), relationship (“rapport”), to build (“costruire”), to deal with (“affrontare”), minority (“minoranza”), challenges (“sfide”), and current events (“attualità”), it becomes evident that this thematic cluster frames interreligious dialogue primarily as a response to contemporary socio-political issues involving the Muslim minority in Italy. The emphasis on building (“costruire”) relationships suggests a constructive, yet often problematized, effort to navigate the challenges (“sfide”) of coexistence. In this representation, dialogue is not focused on theological exchanges but on how Italy manages a religious minority (“minoranza”) through the lens of state affairs (“attualità”) and security, as well as integration and assistance policies (“integrazione”, “aiutare”). In general, we can interpret this media representation of interreligious dialogue as a strategy for managing coexistence, integration, and public discourse surrounding Islam in a predominantly Catholic country like Italy. It also highlighted the political significance, as well as the tensions and the clash between different perspectives within the Italian public debate regarding the presence of Islam in Italy.

The second topic (gray), which we interpret as “the Catholic perspectives on interreligious dialogue”, revolves around the Catholic Church’s formal discourse on interreligious dialogue, with frequent references to the Second Vatican Council, official documents, and ecclesiastical figures.1 This thematic cluster reflects a normative and definitional register, in which dialogue is understood primarily through doctrinal statements, theological reflections, and the institutional role of the Catholic Church. By examining the words most strongly associated with this topic—such as openness (“aperture”), recognition (“riconoscimento”), to consider (“considerare”), and diversity (“diversità”)—we can understand how this thematic cluster constructs interreligious dialogue as a principled and institutional commitment of the Catholic Church. The presence of words such as openness (“aperture”) and recognition (“riconoscimento”) signals an attitude of receptivity and mutual acknowledgment, rooted in the Church’s official stances (“Concilio”) (Nostra Aetate 1965). In this media representation, dialogue is not portrayed as spontaneous or informal, but rather as a structured process in which the Catholic Church considers (“considerare”) other religions—or more broadly the religious diversity (“diversità”)—as its own theological and pastoral concern. This vocabulary—as dialectic (“dialettica”), accent (“accento”), and Latin (“latino”)—confirms the topic’s alignment with a formal and doctrinal understanding of interreligious dialogue, reflecting the Catholic Church’s role as the authoritative voice in shaping its meaning and scope.

The third topic (green), which we titled “Pope Francis and the interreligious encounter,” highlights the central role of Pope Francis (“Francesco”) in shaping contemporary approaches and initiatives on interreligious dialogue. This cluster is distinguished by a vocabulary centered around Pope Francis, such as his visits, speeches, and symbolic messages (“messaggi”), particularly those involving leaders of other Abrahamic faiths. The frequent use of the words “to know” (“conoscere”) and “understand” (“capire”) suggests a model grounded in mutual comprehension and personal encounter, while references to the “Jewish question” (“questione ebraica”) reflect the Pope’s commitment to historical awareness and reconciliation (Phan 2022). Thus, this media representation conveys a personalized and performative dimension of dialogue, where Francis’s gestures of openness and bridge-building are presented as tangible expressions of interfaith engagement. Through these elements, the vocabulary of this topic constructs a perspective of interreligious dialogue that is relational, ethically grounded, and embedded in the symbolic authority of the papacy.

The fourth topic (blue), titled “Islamic communities and the intercultural challenge,” focuses on the role of grassroots initiatives and local engagement in fostering interreligious dialogue, particularly through the activities of Islamic cultural centers (“centro islamico”) and community associations (“associazioni”). The vocabulary associated with this cluster reflects a practical and civic-oriented dimension of dialogue, with recurring terms such as school (“scuola”), Islamic (“islamica”), and promotion (“promozione”), suggesting a setting where intercultural exchange takes place in everyday contexts. These include educational environments, youth programs, and neighborhood-level efforts aimed at building mutual understanding and integration. The articles grouped in this topic often highlight how Islamic institutions contribute to social cohesion and intercultural dialogue, not through high-level theological debates, but through the concrete actions of teaching, organizing, and engaging with local communities. Consequently, dialogue here is portrayed as a lived, participatory process, rooted in the shared spaces and routines of multicultural urban life.

Finally, the fifth topic (purple), which we interpret as “Interreligious dialogue within the institutional framework of the Catholic Church”, concentrates on the structured and institutionalized dimension of interfaith engagement as managed by the Catholic Church. Unlike topic 2, which focuses on theological and doctrinal definitions, this topic emphasizes the organizational aspects of interreligious dialogue. The vocabulary here includes terms such as diocesan office (“ufficio diocesano”), diocese (“diocesi”), commission (“commissione”), director (“direttore”), group (“group”), and episcopal (“episcopale”), all of which point to the Catholic Church’s mechanisms for coordinating interfaith initiatives. These efforts often involve formal structures such as commissions, episcopal guidelines, and diocesan activities designed to implement the Catholic Church’s practical commitment to interreligious dialogue. This media representation captures the managerial and operative side of Catholic interreligious outreach, showing how dialogue is embedded in institutional routines, ecclesial planning, and the broader infrastructure of the Catholic Church.

Looking at Figure 2, it presents a semantic mapping of the keywords extracted from the corpus of newspaper articles through topic modeling. The terms are color-coded following that of the topics in Figure 1, and spatially distributed to reflect thematic proximity, with each cluster suggesting a coherent field of discourse. The top-left quadrant, predominantly colored in red, green, and gray (respectively, topics 1, 3, and 2), highlights terms such as “Ratzinger”, “Bergoglio”, pontiff (“pontefice”), cardinal (“cardinale”), faith (“fede”), Council (“concilio”), and Jerusalem (“Gerusalemme”). These terms point to an overarching focus on the institutional and theological dimensions of the Catholic Church, including references to ecclesiastical hierarchy, Catholic tradition, and interreligious dialogue. The presence of the words Islam (“islam”), Hebrew (“ebraico”), Russian Patriarch Kirill (“kirill”), Muslim (“musulmano”), population (“popolazione”), dialogue (“dialogo”) indicates a strong emphasis on interfaith engagement, especially with Judaism and Islam. This suggests a media representation constructed around the Catholic Church’s relationship with other Abrahamic traditions, often articulated in global or geopolitical terms.

Figure 2.

The proximity and overlapping among the topics.

In contrast, the top-right quadrant colored mainly in purple (topic 5) features words such as bishop (“vescovo”), father (“don”), parish (“parrocchia”), diocese (“diocese”), pastoral (“pastorale”), synod (“sinodo”), Italian Episcopal Conference (“cei”), and celebration (“celebrazione”). This cluster appears to be more grounded in local ecclesial life and pastoral practice, with a minor presence of the green cluster (topic 3) focused on Jewish-Christian dialogue. Here, the discourse centers on diocesan structures, clerical figures, liturgical events, and the everyday functioning of Catholic parishes and groups at a local level. While the top-left quadrant reflects more global and doctrinal Catholic concerns, this right space foregrounds local Catholic dynamics and actors involved in community life.

The bottom-right quadrant, composed mainly of purple and light blue terms (respectively, topics 5 and 4), continues the theme of community but with a broader sociocultural framing. Terms like party (“festa”), journey (“cammino”), organize (“organizzare”), association (“associazione”), hall (“salone”), education (“formazione”), university (“università”), and event (“evento”) suggest a connection to public initiatives, educational programs, and youth activities. This cluster blends religious language with that of youth in educational settings, indicating a communicative zone where interfaith initiatives led by the Catholic Church overlap with public institutions. The presence of professor (“docente”), university (“università”), and faculty (“facoltà”) further reinforces the educational orientation of this region of the plot, tracing an article’s discourse addressing faith-based involvement in cultural and/or academic contexts.

The bottom-left quadrant, dominated by blue and red tones (respectively, topics 4 and 1), diverges again from formal doctrinal discourses on interreligious dialogue. Words like minister (“ministro”), delegate (“delegato”), citizenship (“cittadinanza”), young person (“giovane”), coordinator (“responsabile”), institutions (“istituzioni”), hospitality (“accoglienza”), and freedom (“libertà”) mark this area as related to political, administrative, and social issues. The prominence of integration (“integrazione”), immigration (“immigrazione”), territory (“territorio”), and foreign (“straniero”) implies coverage of themes such as migration policy, multiculturalism, and governance, which may intersect with interreligious affairs but are framed in a political vocabulary. This area appears to host articles in which the Catholic Church participates in public debates about policies, humanitarian work, and social justice, often extending its commitments to broader societal concerns.

Despite the differentiation between these media representations, certain words and themes reveal important overlaps. For instance, terms related to key concepts such as identity, community, and values appear in multiple areas, functioning as bridges between doctrinal, pastoral, and political discourses. Similarly, the term topic (“tema”) is placed near the center, perhaps acting as a semantic pivot that links various topical frameworks. Nevertheless, there is a notable division between vertically aligned clusters: the left-hand side favors abstract, theological, and geopolitical concerns, whereas the right-hand side emphasizes practical, local, and interpersonal dimensions.

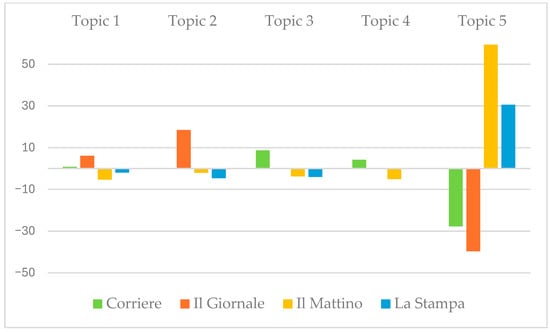

Lastly, to deepen our analysis, the identified media representations were cross-referenced with the newspapers, enabling a clear visualization of “who says what”. This relationship was measured through the association of each topic with the respective newspaper, based on χ2 contributions. The resulting graph (Figure 3) provides a nuanced picture of how different newspapers prioritize and frame interreligious dialogue.

Figure 3.

The association among topics and newspapers.

Topic 1 is predominantly associated with Il Giornale. This topic focuses primarily on Islam as a sociopolitical issue within the Italian context, reflecting the editorial priorities of Il Giornale—which places significant emphasis on related controversial issues. Similarly, topic 2, which is centered on the historical perspectives and the doctrine on interreligious dialogue by the Catholic Church, is also mainly covered by Il Giornale. In contrast, topics 3 and 4 find their strongest presence in Corriere della Sera. Specifically, topic 3 highlights the personal and symbolic role of Pope Francis in fostering interreligious encounters, while topic 4 emphasizes everyday intercultural and interreligious engagements and challenges with Islamic communities at the local level—thus aligning with Corriere’s editorial focus on immigrants’ integration and intercultural efforts.

Finally, topic 5, which concerns mainly the organizational and institutional structures of interreligious dialogue within the Catholic Church, is primarily represented in La Stampa and Il Mattino. These newspapers tend to foreground the Catholic Church as the principal actor in institutionalizing interfaith dialogue through diocesan offices, commissions, and episcopal authority. This differentiated positioning of the newspapers reveals how political orientations and editorial agendas shape the journals’ framing of interreligious dialogue: Il Giornale is more centered on hot issues surrounding Islam and the institutional role of the Catholic Church (topics 1 and 2); Corriere della Sera focuses more on dialogue as a process of integration and minority engagement related to Islam as well as to the contribution of Pope Francis’s leadership (topics 3 and 4); while La Stampa and Il Mattino emphasize the institutional organization of interreligious dialogue by the Catholic Church (topic 5).

Together, these five media representations, along with their association with specific newspapers, offer a multifaceted picture of how interreligious dialogue is outlined in the Italian press. As we have seen in the previous graphs (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3), the main topics range from political and institutional framings to more personal, symbolic, and community-based interpretations. Moreover, the thematic distribution across the different newspapers underscores not only the diversity of actors and discourses involved in interreligious dialogue but also the complex and politically nuanced ways in which this topic is discursively constructed by the Italian media landscape.

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

This study presents an exploratory investigation into the representations of interreligious dialogue in the Italian press, based on a corpus of 1186 articles published between 2010 and 2023. While the findings offer meaningful insights, several limitations must be acknowledged. Foremost, the relatively small corpus, restricted to four newspapers, calls for additional expansion. Future studies should incorporate other newspapers, including regional and confessional outlets, to achieve a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of media representations and related discursive strategies. However, the findings may be organized under four key points.

Firstly, the episodic and fragmented nature of interreligious initiatives, as reflected in media coverage, limits the potential for establishing consistent discursive patterns. Interfaith dialogue tends to appear in the press in response to specific events—papal visits, local initiatives, or interreligious or geopolitical tensions—rather than as part of a sustained topic addressed in the Italian public debate. This sporadic visibility contributes to a fragmented perspective, which is heavily dependent on the presence of key actors such as Pope Francis and other Catholic leaders or on politicized themes such as issues surrounding Islam. In short, one could argue that the topic of interreligious dialogue is neither substantial nor deeply rooted in the Italian press but rather a topic periodically “revived” through local engagements or as a “reflection” of the Pope’s (often international) agenda (Giordan and Lynch 2019).

Secondly, from a general standpoint, our findings suggest that the Catholic Church remains the central actor in the media’s framing of interreligious dialogue in the Italian context. The dominant media representations revolve around a Catholic institutional approach, with references to its doctrine, history, ecclesiastical structure, and leadership (Phan 2016). Minority religious communities, especially Islam, are mostly visible in political debates or local intercultural initiatives, rather than as independent actors in dialogue. This contributes to a vision of interreligious engagement that is both hierarchical and unbalanced in its representation. The results also raise the broader question about the influence of the Catholic Church on the Italian media system and the public visibility of religious diversity (Mazzei 1997).

Thirdly, the widespread portrayal of Islam as a “problematic religion” is often linked to the broad narrative of a so-called “clash of civilizations” (Huntington 1993). These representations contribute to framing Islam as inherently at odds with Western values, thereby reinforcing perceptions of incompatibility. As a result, references to the challenges related to the sociocultural coexistence with Islam—both in Italy and globally—become central to journal articles and, more broadly, to media debates (Klinkhammer 2020). Such discourses tend to blur the internal diversity of Muslim traditions or communities and their engagements with Italian society, as well as overlook the socio-political dynamics that shape integration, shifting attention to identity politics and geopolitical issues. More broadly, this media representation also shows how Islam is framed as a political issue associated with security in the West and in Europe, revealing the bonds between Islam and governmental as well as socio-political approaches to security concerns (Bonino and Ricucci 2021).

Fourthly, a general representation of interreligious dialogue often centers around the Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—while marginalizing or excluding other religious minorities (Griera and Nagel 2018). This selective focus contributes to shaping a narrow understanding of religious diversity, which overlooks the presence and contributions of traditions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Pentecostalism, Adventism, the Bahá’í faith, and various denominations and new religious movements. Thus, journals’ articles about interfaith dialogue tend to reflect a hierarchical vision of religions, where some are more dialogically relevant than others. This dynamic reinforces patterns of exclusion and invisibility for less represented and influential religious communities within pluralistic societies.

Against this backdrop, media representations of interreligious dialogue in Italy are shaped by the political orientations and the agenda of the newspapers. A conservative-leaning newspaper, such as Il Giornale, tends to emphasize conflictual or securitarian framings of Islam, while also promoting a more traditional vision of Catholic identity. By contrast, Corriere della Sera outlines interreligious dialogue through the lens of immigrants’ integration and sociocultural inclusion, highlighting the role of Pope Francis as a bridge-builder at national and global levels. Il Mattino and La Stampa, meanwhile, appear more focused on the institutional organization of interfaith initiatives led by the Catholic Church, especially at the local level. In short, the interreligious dialogue in the Italian press is depicted through a spectrum of representations, ranging from abstract doctrine to grassroots intercultural practice (Winkler et al. 2023), yet remains primarily centered on the Catholic Church’s perspectives and institutional framework. The contrast across newspapers reveals how editorial lines shape both the visibility and framing of religious pluralism in Italy (Guglielmi 2022; Guglielmi et al. 2024; Pace 2013), offering fertile ground for future research into the intersection of media and religious diversity in pluralistic societies.

To conclude, this study underscores the complexities and nuances of how interreligious dialogue is represented in Italian newspapers. The quali-quantitative content analysis reveals a landscape where religious dialogue is often framed within institutional, political, and cultural discourses that reflect broader societal attitudes toward religious diversity. Furthermore, the study highlights the Catholic Church’s dominant role in shaping the media account on interreligious dialogue, reinforcing its centrality in discussions of faith-based interactions in the Italian peninsula. Meanwhile, Islam remains a focal point of contention, often discussed in relation to challenges of integration and societal tensions, which may contribute to a polarized public perception of interfaith relations in Italy. With that respect, the recurrence of bridging terms underscores the interconnected nature of the Abrahamic traditions, suggesting that media portrayals of the Italian religious diversity and its constituent religions are frequently interwoven through dialogue (Körs et al. 2020).

By examining the above media representations, this research contributes to a broader understanding of the role of the press in shaping public discourse on religious pluralism. It also provides a foundation for future sociological studies exploring interfaith dialogue in different media landscapes and cultural contexts. As described in the introduction (Section 1) referring to the “Fourth Estate” (Macknight 1858), the press is not merely a passive reflector of social reality but an active agent in constructing representations and discourses around interreligious dialogue. These latter can foster either mutual understanding or exclusion among religious communities in diverse societal settings—such as the Italian context explored in this study—and address geopolitical tensions in different ways.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, M.G. and S.S.; Writing—review & editing, M.G. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [the European Union—Next Generation EU] grant number [MUR PRIN 2022, PROT. 2022NPTNEZ].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | Below is the link to the website of the Vatican Dicastery for Interreligious Dialogue, which includes documents and ecclesial figures: https://www.vatican.va/content/romancuria/it/dicasteri/dicastero-dialogo-interreligioso.index.html (last access: 5 August 2025). |

References

- Aroldi, Piermarco, Giuseppe Giordan, and Stefano Sbalchiero. 2024. La copertura informativa degli abusi sessuali nella Chiesa cattolica: Un’analisi di tre testate giornalistiche italiane (2018–2022). Problemi dell’informazione, 263–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bantimaroudis, Philemon. 2007. Media Framing of Religious Minorities in Greece: The Case of the Protestants. Journal of Media and Religion 6: 219–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonino, Stefano, and Roberta Ricucci, eds. 2021. Islam and Security in the West. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W., and Vicki L. Plano Clark. 2011. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Deterding, Nicole M., and Mary C. Waters. 2021. Flexible Coding of In-depth Interviews: A Twenty-first-century Approach. Sociological Methods & Research 50: 708–39. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, Hent, and Samuel Weber, eds. 2001. Religion and Media. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, Robert Mathew. 1993. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 43: 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, Robert Mathew. 2007. Framing Bias: Media in the Distribution of Power. Journal of Communication 57: 163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordan, Giuseppe, and Andrew P. Lynch, eds. 2019. Interreligious Dialogue: From Religion to Geopolitics. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Giordan, Giuseppe, and Enzo Pace, eds. 2014. Religious Pluralism: Framing Religious Diversity in the Contemporary World. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Greenacre, Michael J. 1984. Theory and Application of Correspondence Analysis. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griera, Mar, and Alexander-Kenneth Nagel, eds. 2018. Special Issue: Interreligious Relations and Governance of Religion in Europe. Social Compass 65: 301–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmi, Marco. 2022. The Romanian Orthodox Diaspora in Italy: Eastern Orthodoxy in a Western European Country. Cham: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi, Marco, Olga Breskaya, and Stefano Sbalchiero. 2024. Catholic Parishes and Immigrants in Italy: Insights from the Congregations Study in Three Italian Cities. Societies 14: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Stuart. 1997. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, Davi E. J. 2011. Theorizing Religion and Media in Contemporary Societies: An Account of Religious ‘Publicization’. European Journal of Cultural Studies 14: 626–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, Seyed Hassan. 2008. Religion and Media, Religious Media, or Media Religion: Theoretical Studies. Journal of Media and Religion 7: 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, Samuel. 1993. The Clash of Civilizations? Foreign Affairs 72: 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinkhammer, Gritt. 2020. Interreligious Dialogue Groups and the Mass Media. Religion 50: 336–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körs, Anna, Wolfram Weisse, and Jean-Paul Willaime, eds. 2020. Religious Diversity and Interreligious Dialogue. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lebart, Ludovic, Alain Morineau, and Kenneth M. Warwick. 1984. Multivariate Descriptive Statistical Analysis: Correspondence Analysis and Related Techniques for Large Matrices. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Lövheim, Mia. 2019. The Swedish Condition: Representations of Religion in the Swedish Press 1988–2018. Temenos 55: 271–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macknight, Thomas. 1858. For the Liberty of the Press: History of the Life and Times of Edmund Burke. London: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Maweu, Jacinta. 2021. Catalysts of Conflict or Messengers of Peace? Promoting Interfaith Dialogue between Christians and Muslims in Kenya through the Media. In Media, Conflict and Peacebuilding in Africa. Edited by Jacinta Maweu and Admire Mare. Abington: Routledge, pp. 113–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzei, Luciano. 1997. Chiesa e Informazione: I Mass Media della Santa Sede. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit, and Annelies Moors, eds. 2005. Religion, Media, and the Public Sphere. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neumaier, Anna, and Gritt Klinkhammer, eds. 2020. Interreligious Contact and Media. Religion 50: 321–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoli, Benedetta, Stefano Sbalchiero, and Brandon Vaidyanathan. 2024. The Enchantment of Science: Aesthetics and Spirituality in Scientific Work. Sociology of Religion 86: 50–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nostra Aetate. 1965. Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions: Nostra Aetate. Vatican. October 28. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_decl_19651028_nostra-aetate_en.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Pace, Enzo. 2011. Religion as Communication: God’s Talk. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, Enzo, ed. 2013. Le Religioni nell’Italia che Cambia: Mappe e Bussole. Rome: Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, Peter C. 2016. Interreligious Dialogue. In Where We Dwell in Common: Pathways for Ecumenical and Interreligious Dialogue. Edited by Gerard Mannion. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, Peter C. 2022. Pope Francis and Interreligious Encounter. Theological Studies 83: 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-de Wit, Anneke, Peter Versteeg, and Johan Roeland. 2015. Contextual Responses to Interreligious Encounters Online. Social Compass 62: 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, Elizabeth. 2002. Reporting Islam: The Media and Representations of Muslims in Britain. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Ratinaud, Pierre. 2014. IRaMuTeQ: Interface de R Pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires [Software, Version 0.7 alpha 2]. Available online: http://www.iramuteq.org (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ratinaud, Pierre, and Pascal Marchand. 2015. Des mondes lexicaux aux représentations sociales. Une première approche des thématiques dans les débats à l’Assemblée nationale (1998–2014). Mots. Les Langages Du Politique 108: 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, Max. 1983. Une méthode de classification descendante hierarchique: Application a l’analyse lexicale par context. Les Cahiers de l’Analyse des Données 8: 187–98. [Google Scholar]

- Reinert, Max. 1993. Les «mondes lexicaux» et leur «logique» à travers l’analyse statistique d’un corpus de récits de cauchemars. Language et Société 66: 5–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sbalchiero, Stefano. 2018. Topic Detection: A Statistical Model and a Quali-Quantitative Method. In Tracing the Life-Course of Ideas in the Humanities and Social Sciences. Edited by Arjuna Tuzzi. Cham: Springer, pp. 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Stolow, Jeremy. 2005. Religion and/as Media. Theory, Culture & Society 22: 119–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzzi, Arjuna. 2024. Fondamenti di Analisi dei Dati Testuali. Rome: Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, Teun A. 1991. Racism and the Press. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, Teun A. 1998. Ideology: A Multidisciplinary Approach. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Veluru, Suresh, B. B. Gupta, Yogachandran Rahulamathavn, and Muttukrishnan Rajarajan. 2014. Privacy Preserving Text Analytics: Research Challenges and Strategies in Name Analysis. In Handbook of Research on Securing Cloud-Based Databases with Biometric Applications. Edited by Deka Ganesh Chandra and Sambit Bakshi. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 354–85. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, Jan, Laura Haddad, Julia Martínez-Ariño, and Giulia Mezzetti, eds. 2023. Interreligious Encounters in Europe: Sites, Materialities and Practices. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Winston, Diane, ed. 2012. The Oxford Handbook of Religion and the American News Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Stuart A. 1997. Media Coverage of Unconventional Religion: Any “Good News” for Minority Faiths? Review of Religious Research 39: 101–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).