Integration and Symbiosis: Medievalism in Giulio Aleni’s Translation of Catholic Liturgy in Late Imperial China

Abstract

1. Translating Liturgy and Christian Missionary History in China: A Historical Overview

2. Contextualizing Giulio Aleni in the History of Translating Catholic Liturgy in China

3. Translating “Anima”: Traces of Aristotelianism and Thomism

Denique non, sicut quidam uolunt, anima sola hoc mysterio pascitur, quia non sola redimitur morte Christi et saluatur, uerum etiam et caro nostra per hoc ad inmortalitatem et incorruptionem reparatur.

Finally, it is not, as some claim, the soul alone that is nourished by this mystery; for it is not the soul alone that is redeemed and saved by the death of Christ, but the body as well is through this restored to immortality and incorruption.(translation mine)8

3.1. Echoes with Medieval Aristotelianism

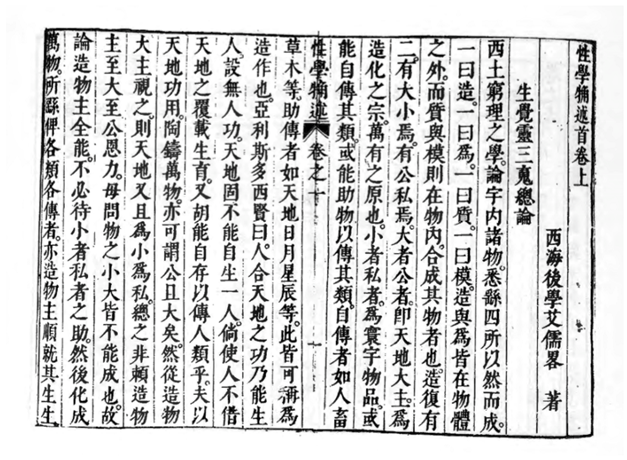

西土窮理之學,論宇內諸物,悉繇四所以然而成。一曰造,一曰為。一曰質。一曰模。造與為皆在物體之外。而質與模則在物內。合成其物者也。

The Western learning about the investigation of principles (i.e., metaphysics) explains all things under heaven as being constituted by four types of “so-therefores” (i.e., causes). The first is creation (efficient cause), the second function/making (i.e., final cause), the third matter (i.e., material cause), and the fourth form (i.e., formal cause). Creation and function (or making) are both external to the physical object, whereas matter and form are within the object. Together they constitute the thing.(translation mine)9

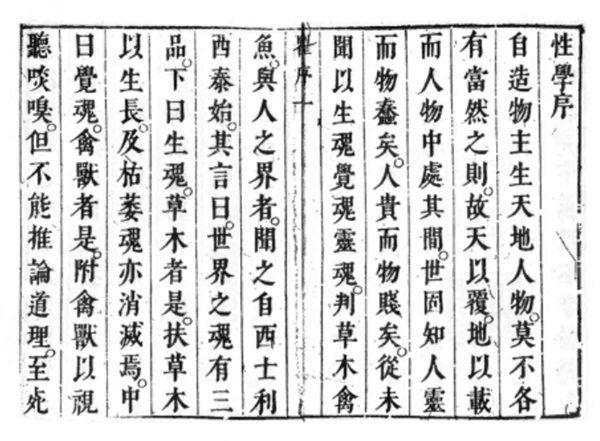

自造物主生天地人物,莫不各有當然之則 … 世固知人靈而物蠢矣,人貴而物賤矣,從未聞以生魂、覺魂、靈魂判草木禽魚與人之界者,聞之自西士利西泰始。其言曰: “世界之魂有三品。下曰生魂,草木者是,扶草木以生長,及枯萎,魂亦消滅焉。中曰覺魂,禽獸者是…”

Since the Creator produced heaven, earth, human beings, and things, they all follow their own principle. … It is known that human beings are sensible whereas things are insensible; human beings are worthy, whereas things are worth less. Yet it was never known until Matteo Ricci that the difference between plants, birds, and fishes on the one hand, and human beings on the other, lies in the vegetative soul, the sensitive soul, and the intellective soul. Ricci argues that souls are divided into three categories. The lowest one is the vegetative soul pertinent to plants, which enables plants to grow; when the vegetative soul vanishes, plants wither. The advanced one is the sensitive soul, pertinent to birds and beasts…(edited and translated, Meynard and Pan 2020, pp. 70–71)

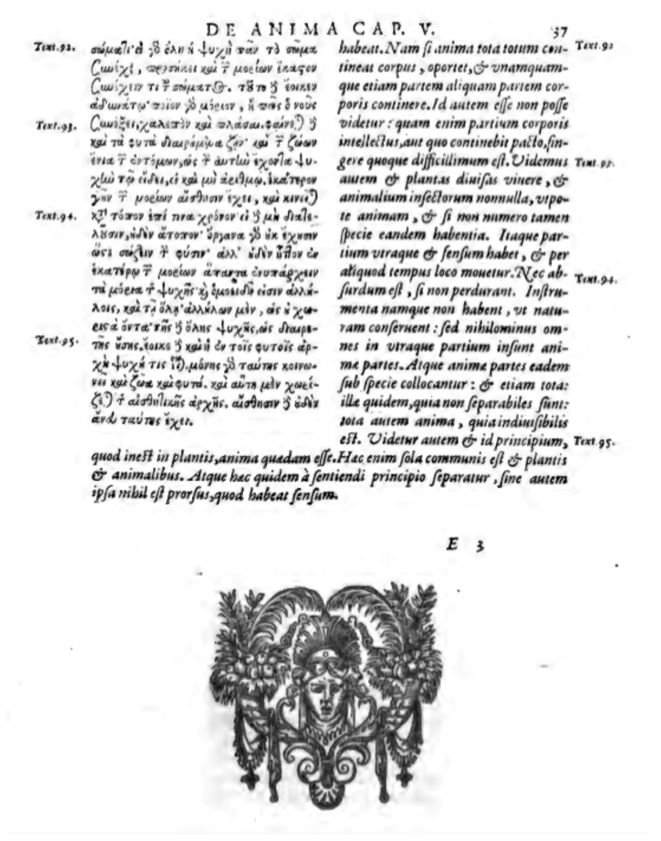

ἔοικε δὲ καὶ ἡ ἐν τοῖς φυτοῖς ἀρχὴ ψυχή τις εἶναι: μόνης γὰρ ταύτης κοινωνεῖ καὶ ζῷα καὶ φυτά·καὶ αὕτη μὲν χωρίζεται τῆς αἰσθητικῆς ἀρχῆς, αἴσθησιν δ᾽ οὐθὲν ἄνευ ταύτης ἔχει.(De anima, ed. Hicks, Aristotle 1907, Book I, Chapter V, Lection XIV, pp. 46–47)

Videntur autem & id principium, quod inest in plantis, anima quædam esse. Hæc enim sola communis est & plantis & animalibus. Atque hæc quidem à sentiendi principio separator, sine autem ipsa nihil est propsus, quod habeat sensum.(De anima, from early print, p. 37, Text 95)

It seems, moreover, that the principle present in plants is a kind of soul. For this alone is common to both plants and animals. And this is indeed distinct from the principle of sensation; yet without it, there is absolutely nothing that possesses sensation.(translation from Latin mine)

3.2. Echoes with Thomistic Scholastic Philosophy

造復有二,有大小焉,有公私焉。大者公者,即天地大主。為造化之宗。萬有之原也。小者私者,為寰宇物品。或能自傳其類,或能助物以傳其類。自傳者如人畜草木等。助傳者如天地日月星辰等。此皆可稱為造作也。

Creation (or efficient causality) is again of two types: there are great and small, public and private forms. The great or public one is the supreme Lord of Heaven and Earth, the source of transformation and the origin of all beings. The small or private ones are worldly things; some can reproduce their own kind, some assist others in reproducing their kind. Self-replicating things include humans, animals, plants, etc.; those that assist reproduction include heaven, earth, sun, moon, stars, etc. All these can be called “causers” or makers (i.e., efficient causes).(translation mine)11

Deus non solum universalem providentiam de rebus corporalibus habeat, sed etiam ad res singulas eius providentia se extendat.

God not only exercises universal providence over corporeal things, but His providence also extends to individual things.

質者物之材料,乃有形諸物所用以成就其體者也。質者有二。一元質。一次質。元質是造物主自生天地之初,備為千變萬化之具。此質非天非地,非水非火,非陰非陽,非寒非暑,非剛非柔,非生非覺,而能成天地水火陰陽寒暑剛柔生覺之種種也。蓋凡物皆有生息,有變滅,而元質則不生不變,常存不亾。為造化基,萬象所共,庶類所同者。…… 乃受生於造物主,開闢天地之初者也。

Matter (zhi 質) is the material of things; it is that by which all visible things achieve the completion of their substance. There are two kinds of matter: one is prime matter (yuanzhi 元質), and the other is secondary matter (cizhi 次質). Prime matter is that which the Creator (zaowuzhu 造物主) produced at the beginning of heaven and earth, prepared as the basis for the myriad transformations and changes. This matter is neither heaven nor earth, neither water nor fire, neither yin nor yang, neither cold nor heat, neither hard nor soft, neither living nor sentient—yet it can become heaven and earth, water and fire, yin and yang, cold and heat, hardness and softness, life and sentience, and all such things. Indeed, all things have life and transformation, generation, and destruction, while prime matter is not born, does not change, and eternally exists without perishing. It is the foundation of creation, shared by all phenomena and common to all beings. … It received its existence from the Creator at the very beginning of the formation of heaven and earth.(translation mine)13

4. From Translating Hylomorphism to Translating Eucharistic Theology

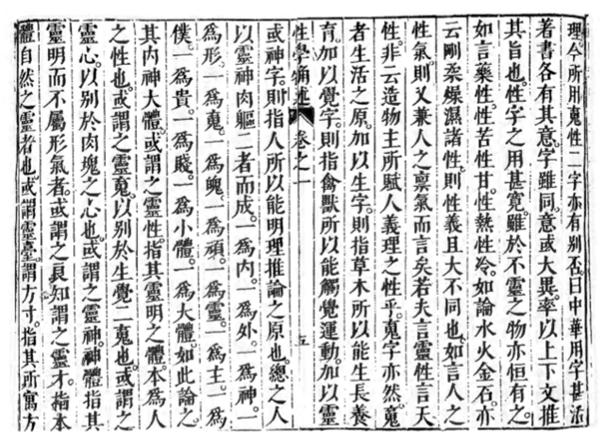

性字之用甚寬,雖然不靈之物亦恆有之。如言藥性,性苦性甘,性冷性熱。如論水火金石,亦雲剛柔燥濕諸性。則性義且大不同也。如言人之性氣,則又兼人之稟氣而言矣。若夫言靈性,言天性,非雲造物主所賦人義理之性乎?魂字亦然。魂者,生活之原。加以生字,則指草木所以能生長養育。加以覺字,則指禽獸所以能觸覺運動。加以靈或神字,則指人所以能明理推論之源也。總之人以靈神肉軀二者而成。一為內,一為外。一為神,一為形。一為魂,一為魄。 一為頑,一為靈。一為主,一為僕。一為貴,一為賤。一為小體,一為大體。如此論之其內神大體,或為之靈性。指其靈明之體,本為人之性也。或謂靈之魂,以別於生覺二魂也。

The use of the term xing (性, nature) is exceedingly broad; even non-sentient things are often said to possess it. For example, we speak of the nature of medicines—some bitter, some sweet, some cold, some hot. Or when discussing water, fire, metal, and stone, we refer to their various natures—hard, soft, dry, moist. Thus, the meaning of “nature” varies significantly across contexts. When we speak of human nature (xingqi, 性氣), it also includes a person’s temperament or innate vital energy. But when we speak of spiritual nature (lingxing, 靈性) or heavenly nature (tianxing, 天性), are we not referring to the rational and moral nature bestowed by the Creator upon humanity? The term hun (魂, soul) is similar in function. Hun refers to the origin of life. If we add the word sheng (生, life) to it, it refers to that by which plants are able to grow and be nourished. If we add the word jue (覺, sensation), it refers to that by which animals are capable of perception and movement. If we further add the word ling (靈, spiritual) or shen (神, divine/intellectual), it refers to that by which human beings are capable of understanding principles and engaging in reasoning. In summary, the human being is composed of two aspects: spirit and flesh. One is internal, the other external. One is spirit, the other form. One is hun, the other po (魄, the corporeal soul). One is dull, the other bright. One is master, the other servant. One is noble, the other is base. One is the lesser part, the other the greater part. In this mode of analysis, the inner spiritual component, the greater part, is referred to as the spiritual nature (lingxing, 靈性). It denotes the luminous and rational principle, which is truly the human nature. Some call it the rational soul, to distinguish it from the vegetative and sensitive souls.(translation mine)

Vnumquodque sortitur speciem per propriam formam. Sed homo est homo in quantum est rationalis. Ergo anima rationalis est propria forma hominis. Est autem hoc aliquid et per se subsistens cum per se operetur: non enim est intelligere per organum corporeum, ut propatur in III De anima. Anima igitur humana est hoc aliquid et forma.

Each thing receives its species through its proper form. But man is man insofar as he is rational. Therefore, the rational soul is the proper form of a human being. Now, this [soul] is also a subsistent thing by and of itself, since it operates through itself; for understanding is not an activity performed through a bodily organ, as is shown in Book III of De Anima. Therefore, the human soul is both a subsistent thing and a form.(Aquinas [1268–1272] 1996, Quaestiones disputatae de anima, vol. I, ll. 176–83; translation mine)

Est igitur accipere aliquid supremum in genere corporum, scilicet corpus humanum aequaliter complexionatum, quod attingit ad infimum superioris generis, scilicet ad animam humanam, quae tenet ultimum gradům ingenere intellectualium substantiarum, utex modo intelligendi percipi potest.

One must therefore consider something supreme within the category of bodies, namely the human body, which is evenly composed and reaches up to the lowest level of the higher category—that is, the human soul, which holds the lowest rank in the order of intellectual substances, as can be understood from its manner of knowing.(translation mine, cf. Sweeney 1999, p. 164)

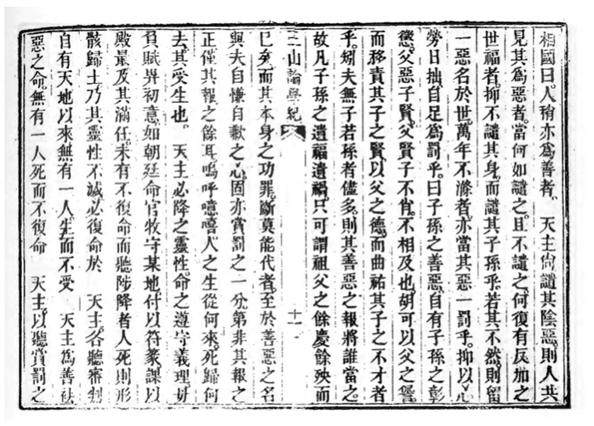

以追遠祭祀之典,證其靈䰟不滅。試觀人於父母旣歿,無不追慕如生,或獻物如在,或祈禱以免其冥苦。若膺一命,必以恩及泉壤爲榮。設使神䰟與身俱滅,縱我致禮,誰爲知者受者? 是爲之祈禱奉祭,祗屬虛僞,而古今大典、萬國眞悃,盡爲可廢也已。

The rituals of ancestral worship prove that the soul is immortal. It is observed that, after their parents have died, people still admire them as if they were alive, or offer sacrifices as if their parents were present; others pray for their parents to escape from the pains after death. If they are knighted, they consider it a badge of honor to have their late parents knighted as well. If the soul were to decay along with the body, who would be the one to know and receive the sacrifice? A corollary of this is that prayers and rituals would be disingenuous, and the solemn rituals practiced in ten thousand countries throughout history should be completely abolished.

人之生從何來,死歸何去?其受生也,天主必降之靈性,命之遵守義禮,毋負賦畀初意。…… 人死則形骸歸土,乃其靈性不滅,必復命於天主,各聽審判。

From where does human life come, and to where does it return in death? When a person receives life, God must bestow upon them a rational soul, commanding them to uphold righteousness and virtue, and not to betray the original purpose granted to them. … When a person dies, the body returns to the earth, but the rational soul does not lessen or perish—it must return to God and await judgment.(translation mine)

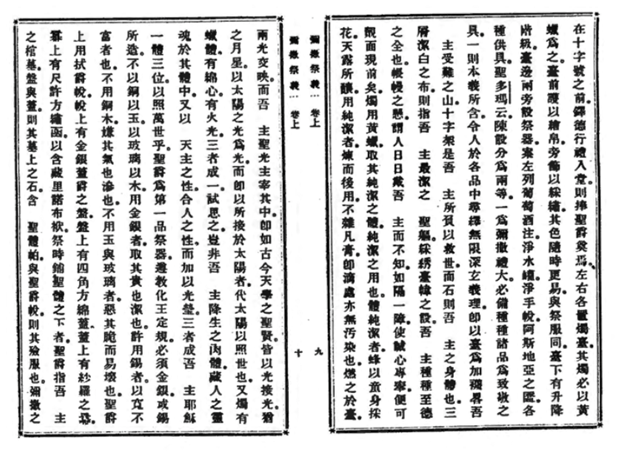

以台為加襪略吾主受難之山;十字架是吾主所負以救世;而石則吾主之身體也。三層潔白之布,則指吾主最潔之聖軀。彩繡台帷 之設,吾主種種至德之全也。帳幔之懸,謂人日日戴吾主而不知,如隔一帳。使誠心專奉,便可覿(音滌)面現前矣。燭用黃蠟, 取其純潔之體純潔之用也。…… 又燭有蠟體,有綿心,有火光,三者成一。試思之,豈非吾主降生之肉軀,藏人之靈魂於其體中。 又以天主之性,合人之性,而加以光瑩。三者成吾主耶穌一體三位,以照萬世乎。

The altar represents Mount Calvary, where our Lord suffered; the cross is what our Lord bore to save the world; and the stone is the body of our Lord. The three layers of white cloth signify the most pure and holy body of our Lord. The embroidered veil of the altar symbolizes the fullness of all our Lord’s virtues. The hanging curtain indicates how people encounter the Lord daily yet do not recognize Him, as if separated by a veil. But if one devoutly and sincerely worships, one may see Him face to face. The candles are made of beeswax, chosen for their purity in substance and function … Furthermore, the candle has a wax body, a wick at its center, and a flame—three in one. Consider this: is it not like our Lord taking on human flesh, with a soul enclosed in that body, and with the divine nature united to human nature, shining forth as radiance? These three—body, soul, and divinity—form one Lord Jesus, a single person, shining upon the world for all time.(translation mine)

Si vero tempore passionis quando sanguis Christi erat ex corpore effusus, fuisset hoc sacramentum ab aliquo apostolorum perfectum, sub panis specie fuisset solum corpus Christi ex sangue, sub speciebus autem vini fuisset solus sanguis Christi.(Summa Theologiae III, q. 76, a. 2, cf. Filip 2009, p. 433)

But if, at the time of the Passion, when the blood of Christ had been poured out from His body, this sacrament had been celebrated by one of the apostles, under the species of bread there would have been only the body of Christ without the blood, and under the species of wine there would have been only the blood of Christ.(translation mine)

Una ratio est, quia tria sunt in hoc sacramento: unum quod est sacramentum tantum, aliud quod est res tantum, aliud quod est sacramentum et res. Sacramentum tantum sunt species panis et vini, res tantum est effectus spiritualis, res et sacramentum est corpus contentum. Si ergo consideremus sacramentum tantum, sic bene competit ut corpus signetur sub specie panis, sanguis sub specie vini, quia signatur ut indicans refectionem spiritualem; sed refectio est proprie in cibo et potu, ideo et cetera. Item si sumatur ut res et sacramentum, ad hoc competit quod illud sacramentum est rememorativum dominicae passionis. Et non potuit melius significare quam sic, ut significetur sanguis ut effusus et separatus a corpore.

One reason is because there are three things in this sacrament: one is the sacramentum tantum, another is the res tantum, and another is the sacramentum et res. The species of bread and wine are the sacramentum tantum, the res tantum is the spiritual effect, the res et sacramentum is the contained body. If therefore we consider the sacramentum tantum, it is properly befitting that the body should be signified under the species of bread and the blood under the species of wine because it is signified as something indicating spiritual refreshment, but refreshment is proper to food and drink…. Likewise, if it is understood as res et sacramentum it is rememorative of the Lord’s passion. And, [the passion] couldn’t have been better signified than this: that the blood be signified as shed and separated from the body.(translation mine, cf. Filip 2009, p. 434)

聖體者何意乎?斯益有三,不可不知也。一曰愛,一曰表,一曰養。養者,五穀以養肉軀,耶穌聖體以養吾之靈魂。…… 聖體知降臨也,比與吾之靈魂,渾合而為一。何養如之?

What is the meaning of the Holy Eucharist? It has three great benefits, which must not be unknown. First is love, second is symbol, and third is nourishment. As grains nourish the body, so the Holy Body of Jesus nourishes our soul. … When the Holy Eucharist descends, it unites with our soul and becomes one with it. What nourishment could be greater than this?

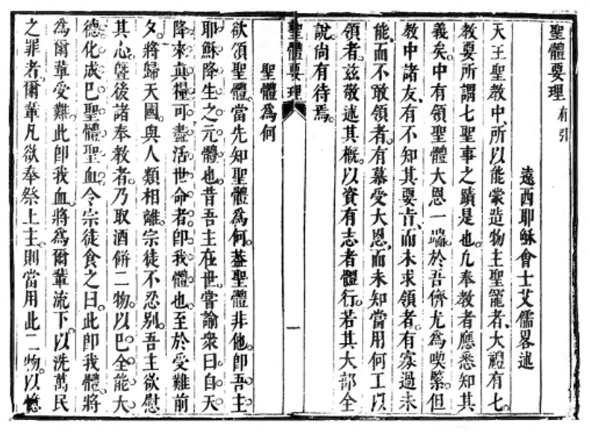

聖體為何?

慾領聖體,當先知聖體為何。蓋聖體非他,即吾主耶穌降生之元體也。昔吾主在世嘗論眾曰:自天降來真糧可盡,活世命者即我體也。至於受難前夕,將歸天國與人類相離。宗徒不忍別。吾主慾慰其心。暨後諸奉教者。乃取酒餅二物。以巳全能大德化成巳聖體聖血。令宗徒食之, 曰此即我體,將為爾輩受難。此即我血, 將為爾輩流下,以洗萬民之罪。

既誦耶穌所定經語於其上,則麥酒之體化為吾主體血與在天無二。雖其麥酒之像色仍存,猶如屏障外掩實不復有麥酒之性質也。…… 西方風俗多以麥為常用之糧。吾主立此大禮。即借飲食養身之物。藏其體血以養靈魂,使人便於領受。

What is the Holy Eucharist?

Before receiving the Holy Eucharist, one must first understand what it truly is. The Eucharist is nothing other than the very body of our Lord Jesus, who took flesh and came into the world. In the past, while our Lord was on earth, He once spoke to the people, saying: “The true bread that comes down from heaven and gives life to the world is my body.” On the eve of His Passion, as He was about to return to the Kingdom of Heaven and be separated from humanity, the apostles could not bear the thought of parting. Wanting to comfort their hearts—and, later, the hearts of all who would believe—our Lord took bread and wine. By His divine power and authority, He transformed them into His own body and blood. He gave them to the apostles to eat, saying: “This is my body, which will be given up for you. This is my blood, which will be poured out for you, to cleanse the sins of all people.”

Once the words that Jesus instituted were spoken over the bread and wine, the substance of wheat and wine was changed into the true body and blood of our Lord, indistinguishable from the Lord who is in heaven. Although the outward appearance of bread and wine remains—like a veil that conceals what is within—the substance of bread and wine no longer exists. In the customs of the West, wheat is the staple food. Our Lord, in establishing this great sacrament, made use of ordinary food and drink to hide His body and blood, to nourish the soul just as food nourishes the body, thus making it easy for people to receive Him.(translation mine)

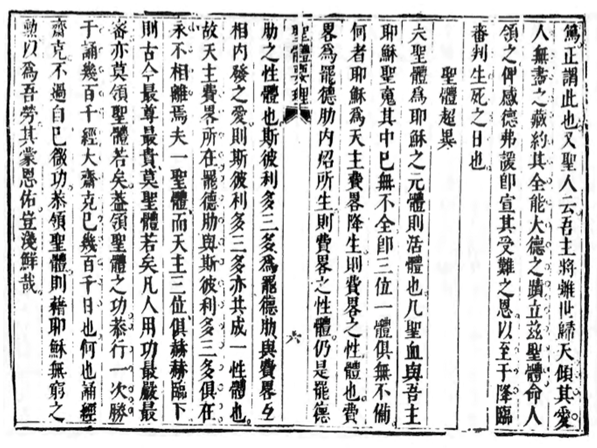

聖體超異

夫聖體為即耶穌之元體,則活體也。凡聖血與吾主耶穌聖魂其中巳無不全,及三位一體,俱無不備 … 為夫一聖體,而天主三位俱赫赫臨下。則古今最尊最貴莫聖體。

The Miracle of the Eucharist

Now, the Eucharist is the very body of Jesus — it is his living body. Within it are truly and fully present his Most Precious Blood and his holy soul, along with the entire Trinity, without anything lacking… In this one Holy Eucharist, all three Persons of the Divine Trinity are gloriously present. Thus, from ancient times to the present, nothing has been more exalted or more precious than the Eucharist.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Portions of this paper were presented at the international conference Il latino e l’Oriente tra l’età medievale e quella moderna: una messa a punto tra storia, letteratura e prospettive digitali (University of Turin, 16–17 June 2025), where the generous feedback of Prof. Andrea Balbo and Prof. Francesco Stella proved especially valuable. I am deeply grateful to both for their kind invitation and their openness in sharing ideas. Conversations—whether around the table, along hiking trails, or during office hours—with Prof. Anthony Bale, Prof. Wolfgang Behr, Prof. Daniel Canaris, Prof. Hans van Ess, Prof. Nathan Gilbert, Prof. Christof Mauch, Prof. Denis Renevey, and Prof. Christiania Whitehead have likewise helped refine my argument. I am particularly indebted to Dr. Mark Mir and Dr. Mårten Söderblom Saarela at the Ricci Institute of Boston College for providing invaluable materials on Giulio Aleni during my archival research there. Finally, I extend sincere thanks to the anonymous reviewers of Religions for their thoughtful critiques and constructive suggestions. Any remaining shortcomings are, of course, my own. |

| 2 | In the Christian tradition, the word “liturgy” comes from the Ancient Greek λειτουργία (leitourgía), which originally meant “public service” or “work done for the people.” It is formed from λαός (laós), meaning “people,” and ἔργον (érgon), meaning “work” or “deed” (Lewis 1960, pp. 175–84). In classical usage, it referred to civic duties performed by citizens for the public good. Early Christians adopted the term to describe their communal worship—especially the Eucharist—as both a service offered to God and a divine work carried out on behalf of the faithful. Over time, “liturgy” came to denote the formal, structured rites of Christian worship, expressing the Church’s shared participation in the redemptive work of Christ. According to the classic definition by Festugière (1914, p. 44), “la liturgie est le culte extérieur que l’Église rend à Dieu, ou plus brièvement, le culte extérieur de l’Église” (The liturgy is the external worship that the Church offers to God, or more briefly, the Church’s external worship). This concise definition is in tune with Callewaert (1925, p. 5), where liturgy is referred to as “cultus publicus ab Ecclesia quoad exercitium ordinatus, seu ordinatio ecclesiastica exercitii cultus publici” (public worship ordered by the Church regarding its exercise, or the ecclesiastical ordering of the exercise of public worship). Concluded in nuce by Jungmann (1931, pp. 83–84), it is “Liturgie ist der Gottesdienst der Kirche – dieser Gottesdienst selbst, nicht nur irgend eine Seite order Erscheinung an ihm. Es ist damit auch der ganze Umkreis von Handlungen und Einrichtungen umschlossen, die wir gewöhnlich liturgisch nennen” (Liturgy is the worship of the Church—this worship itself, not just any one aspect or appearance of it. It therefore also includes the entire range of actions and institutions that we commonly call liturgical). The three definitions of “liturgy” by Festugière, Callewaert, and Jungmann share a central commonality: they all emphasize the Church’s official, communal, and structured act of worship. In the connotative sense, the term “liturgy” evokes a sense of sacred tradition, institutional authority, and the fullness of ritual life, encompassing not only individual ceremonies but the broader framework of actions and structures deemed liturgical. |

| 3 | Institutional translation refers to “those cases when an official body (government agency, multinational organization or a private company, etc.; also an individual person acting in an official status) uses translation as a means of “speaking” to a particular audience. Thus, in institutional translation, the voice that is to be heard is that of the translating institution. As a result, in a constructivist sense, the institution itself gets translated” (Koskinen 2008, p. 22). |

| 4 | Pertinent texts include, for instance, Da Qin Hymn of Perfection of the Three Majesties (大秦景教三威蒙度讚) and Let Us Praise or Venerable Books (尊經), both preserved in MSS Paris, Bib. Nat., Collection Pelliot, chinois no. 3847; The Sutra of Ultimate and Mysterious Happiness (志玄安樂經), held in Kyōu Shooku library, Tonkō-Hikyū Collection, manuscript no. 13 (Osaka, Japan). For details, see Lin and Rong (1996, pp. 5–14). |

| 5 | As a matter of fact, the Jesuits obtained permission to translate the liturgy into Chinese from Paul V in 1615, they never implemented the permission, and the liturgy was still celebrated in Latin. The Chinese vernacular was used for devotional practices, which would be technically considered paraliturgical. |

| 6 | According to Hsia (2007, p. 40), the most remarkable milestone in the history of Jesuit translation of Christian liturgy in China can be ascribed to Ludovico Buglio (利類思 1606–1682)’s completion of the Chinese translation of Missale Romanum in 1670 (known as Misa Jingdian 彌撒經典 or Telunduo Misa Jingshu 特倫多彌撒經書 into Chinese. As a guiding document for Catholic churches across the world, Missale Romanum is a fruit of the Council of Trent (1545–1563); functionally, it ensures doctrinal and liturgical consistency worldwide. The 1570 edition of this text, promulgated by Pope Pius V (1504–1572), became mandatory throughout the Latin Church (Chadwick 2015; Geldhof 2012). While it contains a specification of liturgical calendars, feasts, saints’ days, and seasonal prayers (Advent, Lent, etc.), Missale Romanum also plays an indispensable part in fostering unity in worship throughout the Catholic world. Together with this foundational text of Christian liturgy, Ludovico Buglio also rendered into Chinese Breviarium Romanum (in 1674 as siduo rike 司鐸日課 or Luoma Rike Jing 羅馬日課經, as well as Manuale ad Sacramenta Ministranda Juxta Ritum Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae (in 1675 as Shengshi Dianli 聖事典禮) (Hsia 2007, p. 40). |

| 7 | It is worth noticing that in Tianzhu Jiaoyao 天主教要, the names of the seven Sacramental rites are listed there in their Chinese phonetic equivalents—respectively as badisimo 拔弟斯摩 (for Baptismo), gongfei er’macang 共斐兒瑪藏 (for Confirmatio), gongmengyang 共蒙仰 (for Communio), bai nideng jiya 白尼登濟亞 (for Paenitentia), e’si dele mawengcang 阨斯得勒麻翁藏 (for Estremus unctio), a’erdeng 阿兒等 (for Ordo), madili moniu 瑪地利摩紐 (for Matrimonium) (Ji 2024, p. 33). As for the doctrine of Trinity, it was introduced into China alongside Jesuit liturgical translation slightly later, tracing back to the second volume of Alfonso Vagnone (高一志 1568–1640)’s Jiaoyao Jielue 教要解略 (dated in 1615). In this book, apart from a detailed explanation of the Trinity, the connotations of blessing, the original sin, the twelve apostles, the Ecclesia Sacramento, as well as the three Christian virtues (e.g., belief, hope, and love) are also to varying degrees unpacked (Ji 2024, p. 33). This represents a further step forward, on the underpinning of Ricci’s pre-evangelical translation of the philosophical layers of European worldview, towards more self-conscious, more subjective, and more systematic translation of Christian liturgy. |

| 8 | Regarding the ritualistic bearings between the liturgy and the salvation of the soul, Hermann Platz has eloquently dilated on it in his Zeitgeist und Liturgie (Platz 1921, p. 49) from an insightful modern perspective, which is echoed by Scherzberg (2010, p. 261). Platz here claims that during the Christian sacramental rituals, the liturgy can have an impact upon the soul, evoking the image of Christ as both human and divine in the recipients’ individual experiences of the Eucharist. In this connection, Romano Guardini in his Vom Geist der Liturgie (Guardini 1962, p. 65) further states that the liturgy has an intrinsic performative potential that revolves around the centrality of the soul in the experience of the liturgy (see also Jeggle-Merz 2012, p. 113). |

| 9 | See also Meynard and Pan (2020, pp. 84–85) for another translation. |

| 10 | https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-causality/, accessed on 30 July 2025. |

| 11 | See note 9 above. |

| 12 | The same holds true in the following paragraph from Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae: “cum natura propter determinatum finem operetur ex directione alicuius superioris agentis, necesse est ea quae a natura fiunt, etiam in Deum reducere, sicut in primam causam. Similiter etiam quae ex proposito fiunt, oportet reducere in aliquam altiorem causam, quae non sit ratio et voluntas humana, quia haec mutabilia sunt et defectibilia; oportet autem omnia mobilia et deficere possibilia reduci in aliquod primum principium immobile et per se necessarium…” (Since nature works for a determinate end under the direction of a higher agent, whatever is done by nature must needs be traced back to God, as to its first cause. So, whatever is done voluntarily must also be traced back to some higher cause other than human reason or will, since these can change or fail; for all things that are changeable and capable of defect must be traced back to an immovable and self-necessary first principle…” (Summa Theologiae, Aquinas [1265–1274] 1888–1906, Iª q. 2 a. 3 ad 2; translation mine). |

| 13 | See also Meynard and Pan (2020, pp. 86–89) for another translation. |

| 14 | As much as human nature is perceived as including a rational soul endowed with intellect and will within the domain of Thomism, Aleni also frames lingxing 靈性 (i.e., the rational soul) and tianxing 天性 (i.e., heavenly nature) as the morally rational nature given by the Creator, which is germane to Christian God in Aleni’s discourse. It is remarkable that both before and contemporary to Aleni’s missionary undertaking in China, xing (性) as a Chinese philosophical concept had been interpreted by Jesuit missionaries in China as largely equivalent to the Western category of human “natura” (i.e., nature). Luo (2016, p. 16) has pointed out that xing (性) as a Confucian philosophical term has been translated by François Noël (1561–1729) “sometimes as ‘natura,’ sometimes as ‘natura rationalis’ in his translation of Zhongyong 中庸, one of the four Confucian classics of China. In Zhongyong 中庸, it goes that 天命之謂性, which has been translated (mostly likely by Michele Ruggieri) as “est primum hominibus è coelo data natura, sive ratio” (the first thing given to human beings from heaven is nature, or reason) (quote from Luo 2015, p. 9; English translation mine; for the manuscript, see Rome, Emanuele II Library MS FG [3314] 1185). Luo (2015, p. 8) has offered a succinct summary of how xing 性, as a central concept of Zhongyong 中庸, has been translated by the Jesuits evangelizing in late imperial China. Apart from “natura seu ratio” (nature, or reason, by Ruggieri in Rome, Emanuele II Library, MS FG [3314] 1185) and “caelestis disciplina, seu natura” (heavenly instruction, or reason, in Sinarum Scientia Politico-Moralis, compiled primarily by Philippe Couplet (1623–1693) and firstly published in Paris in 1679), xing 性 has also been interpreted as “natura rationalis” (rational nature, or a nature endowed with reason, in Sinesis Imperii Libri Classici Sex, 1711 Pragae, attributed to François Noël). These examples, as it appears, jointly indicate that in Aleni’s time, explaining the Confucian term xing 性 through the Aristotelian-Thomistic prism as the “natura rationalis” had been widely adopted. Aleni continued with this path as well. |

References

Primary Sources

- Aleni, Giulio. 2011. The Collection of Jules Aleni’s Chinese Works. Edited by Ye Nong. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Aleni, Giulio. 2014. Kouduo Richao 口鐸日抄. In Collected Historical Documents on Sino-Western Cultural Exchange during the Ming and Qing Dynasties from the Vatican Library (梵蒂岡圖書館藏明清中西文化交流史文獻叢刊). Edited by Xiping Zhang, Federico Masini, Dayuan Ren and Ambrogio M. Piazzoni. Zhengzhou: Daxiang Press, pp. 409–730. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1888–1906. Summa Theologiae. Edited by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province. Rome: Ex Typographia Polyglotta S. C. de Propaganda Fide, 3 vols. First published 1265–1274. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1953. Quaestiones disputatae de potential, quaestio VII. Edited by Roberto Busa. Rome: Textum Taurini. Available online: https://www.corpusthomisticum.org/qdp7.html (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1961. Summa contra Gentiles. In Opera Omnia. Edited by P. Marc, C. Pera and P. Caramello. Torino and Rome: Marietti, vols. 13–15. First published 1878. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1996. Quaestiones Disputatae de Anima. In Opera Omnia, 1st ed. Edited by Bernardo Carlos Bazán. Rome: Commissio Leonina, Paris: Éditions du Cerf, vol. 24.1. First published 1268–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, Thomas. 2018. Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew 1–12 (Latin-English Opera Omnia). Steubenville: Emmaus Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle. 1907. De Anima. Edited and Translated by Robert Drew Hicks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collegium Conimbricense Societatis Iesu. 1612. Commentarii Collegii Conimbricensis Societatis Iesu, in tres libros De anima Aristotelis Stagiritae. Lugduni: Sumptibus Horatij Cardon. Available online: https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_aDvN3eh8NokC (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Meynard, Thierry, and Dawei Pan, ed. and trans. 2020. Giulio Aleni’s Xingxue Cushu, i.e., A Brief Introduction to the Study of Human Nature. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggieri, Michele. 2023. Tianzhu Shilu (The True Record of the Lord of Heaven, 1584). Edited by Daniel Canaris. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Abel-Rémusat, Jean-Pierre. 1829. Nouveaux Mélanges Asiatiques: ou recueil de morceaux de critiques et de mémoires relatifs aux religions, aux sciences, aux coutumes, à l’histoire et à la géographie des nations orientales. Paris: Schubart et Heideloff, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

Secondary Sources

- Arnold, Lauren. 1999. Princely Gifts and Papal Treasures: The Franciscan Mission to China and Its Influence on the Art of the West, 1250–1350. Terre Haute: Desiderata Press. [Google Scholar]

- Banchoff, Thomas F., and José Casanova, eds. 2016. The Jesuits and Globalization: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Challenges. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bays, Daniel H. 2011. A New History of Christianity in China. London: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bertuccioli, Giuliano. 2003. Martino Martini’s Grammatica Sinica. Monumenta Serica 51: 629–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, Teresa. 2012. The limits of hylomorphism. Metaphysica 13: 145–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockey, Liam Matthew. 2007. Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579–1724. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Callewaert, Camille. 1925. Liturgicae Institutiones, 2nd ed. Bruges: Carolum Beyaert, Editorem Pontificium, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Canaris, Daniel. 2019. The Tianzhu Shilu Revisited. Frontiers of Philosophy in China 14: 201–25. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, Jose. 2018. Locating Religion and Secularity in East Asia through Global Processes: Early Modern Jesuit Religious Encounters. Religions 9: 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, Anthony J. 2015. The Roman Missal of the Council of Trent. In T&T Clark Companion to Liturgy. Edited by Alcuin Reid. London: T&T Clark, pp. 107–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazelle, Celia. 2012. The Eucharist in early medieval Europe. In A Companion to the Eucharist in the Middle Ages. Edited by Ian Christopher Levy, Gary Macy and Kristen Van Ausdall. Leiden: Brill, pp. 205–49. [Google Scholar]

- Che, Xiangqian. 2024. From Sacred Doctrine to Confucian Moral Practice: Giulio Aleni’s Cross-Cultural Interpretation of “Goodness and Evil of Human Nature”. Religions 15: 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Huaiyu. 2009. The Encounter of Nestorian Christianity with Tantric Buddhism in Medieval China. In Hidden Treasures and Intercultural Encounters: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. Edited by Dietmar W. Winkler and Li Tang. Wien: Lit Verlag, pp. 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Damrosch, David. 2003. What Is World Literature? Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Damrosch, David, and David Lawrence Pike. 2009. Longman Anthology of World Literature. London: Pearson/Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, Christopher, ed. 1955. The Mission to Asia: Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. London: Sheed and Ward. [Google Scholar]

- De Caro, Antonio. 2022. Christianity in China from the Seventh Century to the Sixteenth Century. In The Palgrave Handbook of the Catholic Church in East Asia. Singapore: Springer, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, Max. 2024. The Christian Communities in Tang China: Between Adaptation and Religious Self-Identity. In Buddhism in Central Asia III: Impacts of Non-Buddhist Influences, Doctrines. Edited by Lewis Doney, Henrik H. Sørensen and Yukiyo Kasai. Leiden: Brill, pp. 123–44. [Google Scholar]

- De Gruttola, Raissa. 2024. Franciscans and Latin Language in China: An Introduction to the Missionary Periodical Apostolicum. In Languages of Science Between Western and Eastern Civilizations. Edited by Carlo Ferrari, Fabio Guidetti and Chiara Ombretta. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- De Gruttola, Raissa. 2025. From ‘Franciscans in China’ to ‘Chinese Franciscans’: Franciscan Missionaries and Chinese Assistants, Priests, and Biblical Translators. Religions 16: 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Fangfeng, and Yang Yang. 2025. The Cultural Accommodation and Linguistic Activities of the Jesuits in China in the 16th–18th Centuries. Religions 16: 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudink, Ad. 2002. Tianzhu Jiaoyao, The Catechism (1605) Published by Matteo Ricci. Sino-Western Cultural Relations Journal 24: 38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Farge, William J. 2012. Adapting Language to Culture: Translation Projects of the Jesuit Missions in Japan and China. In Cross-Cultural History and the Domestication of Otherness. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Festugière, Maurice. 1914. La Liturgie Catholique—Données fondamentales et vérités à rétablir. Revue Thomiste 22: 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Filip, Stepan Martin. 2009. Imago Repræsentativa Passionis Christi: St. Thomas Aquinas on the Essence of the Sacrifice of the Mass. Nova et Vetera 7: 405–38. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, John. 1939. The Nestorian Tablet and Hymn: Translations of Chinese Texts from the First Period of the Church in China, 635–c.900. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. [Google Scholar]

- Geldhof, Joris. 2012. Did the Council of Trent Produce a Liturgical Reform? The Case of the Roman Missal. Questions Liturgiques/Studies in Liturgy 93: 171–95. [Google Scholar]

- Golvers, Noël. 2021. The Jesuits as Translators between Europe and China (17th–18th Century). In Missionary Linguistics VI: Missionary Linguistics in Asia. Selected Papers from the Tenth International Conference on Missionary Linguistics, Rome, Italy, 21–24 March 2018. Edited by Otto Zwartjes and Paolo De Troia. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 101–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardini, Romano. 1962. Vom Geist der Liturgie. Freiburg: Herder Bücherei. [Google Scholar]

- Haskell, Yasmin. 2021. Translating Human and Divine Nature between Europe and China. Journal of Jesuit Studies 8: 483–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Xiaochun. 2023. Catholic Intellectuals in Modern China and their Bible Translation: Li Wenyu and Ma Xiangbo. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 33: 443–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, R. Po-chia. 2007. The Catholic Mission and Translation in China, 1583–1700. In Cultural Translation in Early Modern Europe. Edited by Peter Burke and R. Po-chia Hsia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Huc. 1857. Le Christianisme en Chine, en Tartarie et au Tibet. Paris: Gaume et frères, vol. I, pp. 383–433. [Google Scholar]

- Jeggle-Merz, Birgit. 2012. Die Liturgie als heilige Handlung: Zur Dramaturgie liturgischer Feiern. In GottesdienstKunst. Edited by Christian Walti, Angela Berlis and David Plüss. Zürich: Theologischer Verlag, pp. 107–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Qianru. 2024. Study on Giulio Aleni’s Sinicizing Translation of Catholic Liturgy. Ph.D. dissertation, Minzu University of China, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Scott Fitzgerald. 2017. Silk Road Christians and the Translation of Culture in Tang China. Studies in Church History 53: 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungmann, Josef Andreas. 1931. Was ist Liturgie? Zeitschrift für katholische Theologie 55: 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Koiskinen, Kaisa. 2008. Translating Institutions. An Ethnographic Study of EU Translation. Manchester: St. Jerome. [Google Scholar]

- Kunstmann, Friedrich. 1856. Die Missionen in Indien und China im XIIII Jahrhundert. Historisch-Politische Blätter für das katholische Deutschland 37: 225–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lanciotti, Lionello. 1959. Andrea da Perugia, vescovo di Ch’üan-chou (Zayton). Cina 5: 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Naphtali. 1960. Leitourgia and Related Terms. Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 3: 175–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Wushu, and Xinjiang Rong. 1996. Doubts Concerning the Authenticity of Two Nestorian Chinese Documents Unearthed at Dunhuang from the Li’s Collection. China Archaeology and Art Digest 1: 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lippiello, Tiziana, and Roman Malek, eds. 1997. Scholar from the West: Giulio Aleni SJ (1582–1649) and the Dialogue Between Christianity and China. Nettetal: Sankt Augustin. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Ying. 2015. Preliminary Studies on the Latin Manuscript of Zhongyong Collected by Michele Ruggieri S.J. Logos & Pneuma: Chinese Journal of Theology 42: 119–44. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Ying. 2016. The Jesuits’ Latin Translations of the Zhongyong 中庸 During the 17th and 18th Centuries. Journal of Confucian Philosophy and Culture 26: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Menegon, Eugenio. 1994. Un solo Cielo: Giulio Aleni S. J. (1582–1649): Geografia, arte, scienza, religione dell’Europa alla Cina. Brescia: Grafo Edizioni. [Google Scholar]

- Menegon, Eugenio. 2019. “The Habit that Hides the Monk”: Missionary Fashion Strategies in Late Imperial Chinese Society and Court Culture. In Catholic Missionaries in Early Modern Asia: Patterns of Localization. Edited by Nadine Amsler, Andreea Badea, Bernard Heyberger and Christian Windler. London: Routledge, pp. 30–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mungello, David E. 1985. Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology. Stuttgart: Steiner, Studia Leibnitiana Supplementa, vol. XXV. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini-Zani, Matteo. 2021. Past and Current Research on Tang Jingjiao Documents: A Survey. In Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Edited by Peter Hofrichter. London: Routledge, pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Dawei. 2024. One Hundred Years of Echoes: The Influence of the Jesuit Aleni on the Spiritual Life of the Manchu Prince Depei. Religions 15: 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascasius, Radbertus. 1969. De corpore et sanguine domini. Epistola ad Fredugardum. Edited by Beda Paulus. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Pieragastini, Steven. 2023. Jesuits in Modern Far East. Journal of Jesuit Studies 10: 561–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platz, Hermann. 1921. Zeitgeist und Liturgie. München/Gladbach: Volksvereins-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Reece, Bryan C. 2019. Aristotle’s Four Causes of Action. Australasian Journal of Philosophy 97: 213–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, Matteo. 2016. The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven. Translated by Douglas Lancashire, and S. J. Peter Hu Kuo-Chen. Chestnut Hill: Institute of Jesuit Sources, Boston College. [Google Scholar]

- Scherzberg, Lucia. 2010. Liturgie als Erlebnis und Kirche als Gemeinschaft. Theologie. Geschichte. Beihefte: Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kuturgeschichte 1: 253–87. [Google Scholar]

- Soars, Daniel. 2021. Creation in Aquinas: Ex Nihilo or Ex Deo? New Blackfriars 102: 950–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standaert, Nicolas. 1999. Jesuit Corporate Culture as Shaped by the Chinese. In The Jesuits: Cultures, Sciences, and the Arts, 1540–1773. Edited by John W. O’Malley, Gauvin Alexander Bailey, Steven J. Harris and S. J. T. Frank Kennedy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 352–63. [Google Scholar]

- Standaert, Nicolas. 2002. Methodology in View of Contact Between Cultures: The China Case in the 17th Century. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sugirtharajah, Rasiah S. 2018. Jesus in Asia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Jianqiang. 2018. The Earliest Statements of Christian Faith in China? A Critique of the Conventional Chronology of The Messiah Sutra and On One God. Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies 18: 133–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, Michael J. 1999. Soul as Substance and Method in Thomas Aquinas’ Anthropological Writings. Archives d’histoire Doctrinale et Littéraire du Moyen Âge 66: 143–87. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Glen L. 2023. The Cross and Jingjiao Theology. In Silk Road Traces: Studies on Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. Vienna: LIT Verlag, pp. 355–74. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Glen L. 2024. Jingjiao: The Earliest Christian Church in China. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Trakulhun, Sven. 2012. Kulturwandel durch Anpassung? Matteo Ricci und die Jesuitenmission in China. Zeitenblicke: Online journal für die Geschichtwissenschaften 11: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Xueying. 2021. The Concept of the Soul During the Chinese Rites Controversy: The Example of Xia Dachang. Journal of Chinese Religions 49: 169–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Juan. 2018. The Cultural Accommodation of Jesuits Missionaries in China During 1595–1730 and Its Impact on Chinese Muslim Scholars of Han Kitab Literature. Hamdard Islamicus 41: 145–74. [Google Scholar]

- You, Bin, and Qianru Ji. 2023. In Communion with God”: The Inculturation of the Christian Liturgical Theology of Giulio Aleni in His Explication of the Mass (Misa Jiyi). Religions 14: 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xiping. 1999. The Textual Criticism on the Book Entitled “The Doctrine of the Lord of Heaven” (Tianzhu Jiaoyao). Studies in World Religions 4: 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Qi. 2024a. An Analysis of Jesuit Missionary Aleni’s Interpretation of Aristotelian Theory of Perception: Based on Xingxue Cushu in Late Ming China. Religions 15: 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Qi. 2024b. Jesuit Missionary Aleni’s Argumentation Strategy on the Concept of Common Sense: Focusing on the Analysis of Xingxue Cushu. Religions 15: 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Wen. 2024. The Soul and Buddha-Nature in Jesuit–Buddhist Debates in the Late Ming Fujian–Zhejiang Regions. Religions 15: 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Hailin. 2024. Transwriting in Aleni’s Xingxue Cushu: Communicating the Philosophy of Human Nature between the West and Late Ming China. Intellectual History Review 34: 577–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zürcher, Erik. 1987. Giulio Aleni et ses relations avec le milieu des lettrés chinois au XVIIe siècle. Florence: Leo S. Olschki. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, C. Integration and Symbiosis: Medievalism in Giulio Aleni’s Translation of Catholic Liturgy in Late Imperial China. Religions 2025, 16, 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16081006

Cui C. Integration and Symbiosis: Medievalism in Giulio Aleni’s Translation of Catholic Liturgy in Late Imperial China. Religions. 2025; 16(8):1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16081006

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Chen. 2025. "Integration and Symbiosis: Medievalism in Giulio Aleni’s Translation of Catholic Liturgy in Late Imperial China" Religions 16, no. 8: 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16081006

APA StyleCui, C. (2025). Integration and Symbiosis: Medievalism in Giulio Aleni’s Translation of Catholic Liturgy in Late Imperial China. Religions, 16(8), 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel16081006